INNOVATION ASSESSMENT VIA ENTERPRISE INFORMATION

MARKETS

Stephan Stathel, Tobias Kranz

Research Center for Information Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany

Florian Teschner, Clemens van Dinther, Christof Weinhardt

Institute of Information Systems and Management (IISM), Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), Karlsruhe, Germany

Tobias Kullnig

Energie Baden-W

¨

urttemberg (EnBW), Karlsruhe, Germany

Keywords:

Innovation Assessment, Enterprise Information Markets, Information Aggregation, Market Systems.

Abstract:

The assessment and evaluation of ideas and innovations has always been a challenging task in innovation

management. Depending on the business culture, innovation proposals can be reviewed and assessed by

employees in order to get valuable information before the innovation implementation. Employees often have

direct contact to customers and consumers which is of highest importance in innovation management. In

this paper, we present Enterprise Information Markets (EIM) as a tool for innovation evaluation. In a field

experiment at EnBW, one of the biggest electricity suppliers in Germany, we adopted an Information Market

web tool to assess innovation proposals submitted by employees during an innovation workshop in order to

test the success of EIM in an enterprise context. We analyze the motivation of employees as well as their

expectations for a set of innovations compared to the expectations of decision makers. The results show

that EIM are accepted by employees and that markets are a valuable tool for the innovation assessment in

enterprises.

1 INTRODUCTION

Companies have been pursuing innovation manage-

ment for years. Managing ideas with structured pro-

cesses should guaranty that valuable ideas won’t get

lost and innovation processes can be conducted with

success. For example, employees often have good

ideas to improve processes or organizational struc-

tures. Instead of disregarding these ideas, the abil-

ity to innovate is a key success factor for growth

and competitiveness (Christensen and Raynor, 2003).

Following (Corsten et al., 2006),, an innovation con-

sists of 3 major steps: First of all, somebody has to

have an idea (1). If the idea is promising, it will be

worked out to a functioning prototype or a proof of

concept: the invention (2). Last but not least, it must

be rolled out in the market to complete the proper-

ties of an innovation: the diffusion (3). In the follow-

ing, we focus on the assessment of ideas in order to

pick the most promising one out of a pool of ideas en-

gaging employees via Enterprise Information Markets

(EIM).

The evaluation of new ideas and identification of

future trends is a challenging task since it is often

based on vague information and uncertainty due to

long time horizons. In order to complete this task

successfully companies often follow the iterative Del-

phi process of distributing questionnaires and collect-

ing experts opinions. Information Markets (IM) on

the other hand rely on the fact that stock prices carry

and aggregate diverse information in a single attribute

price. (Green et al., 2007) compared both methods to

elicit forecasts from groups. Compared to the Delphi

method, IMs bear the advantage that the results (i.e.

valuations of participants) can be interpreted contin-

uously, that new information can be integrated im-

mediately, and that trading itself is often intuitively

understood by the participants. Furthermore, IMs

are often considered as a method to support “Wis-

dom of Crowds” because they aggregate information

held by many people and have a participative element

(Surowiecki, 2005). On the other hand, trading in IMs

206

Stathel S., Kranz T., Teschner F., van Dinther C., Weinhardt C. and Kullnig T. (2010).

INNOVATION ASSESSMENT VIA ENTERPRISE INFORMATION MARKETS.

In Proceedings of the Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT, pages 206-216

DOI: 10.5220/0003037802060216

Copyright

c

SciTePress

gets cumbersome for large studies with many ques-

tions and low liquidity for very small sample groups.

The use of IMs in the context of innovation processes

and forecasting appears advantageous since the par-

ticipants do not have to exhibit their complete knowl-

edge. Thus, participants use their information to gain

profits from stock trading and report their opinion in-

directly. Additionally, IMs have also a playful aspect.

Soukhoroukova and Spann successfully used IMs

for the assessment product innovation alternatives,

e.g. mp3 players (Soukhoroukova and Spann, 2005).

Compared to conjoint analysis and other methods,

IMs with 8-12 participants are more robust and re-

liable compared to conjoint analysis with 307 partic-

ipants. Spann emphasizes that IMs must have an ap-

propriate amount of traders to work well (Spann and

Skiera, 2004). But people do not want to trade if mar-

kets are thin. One way to add liquidity is the intro-

duction of Market Makers. In financial stock markets

like NYSE or NASDAQ Market Makers are common

in order to provide liquidity. Stathel et al. analyzed

the impact of automated market making in virtual IMs

(Stathel et al., 2009). In a field experiment for the

European Soccer Championship in 2008, the results

show a significant gain in liquidity through the usage

of automated market making.

IMs bear several advantages compared to other

methods for information aggregation like surveys or

nominal group techniques. As traders reveal their ex-

pectations via buying and selling shares representing

a future event, the trading success can be bound to

a performance based incentive system. The better

a participant trades in the market, the more he gets

compensated either with prizes or real money. Hence,

this powerful incentive mechanism motivates people

to stay active in the Information Market. Furthermore,

people in IMs are a subject to the so-called “self selec-

tion” process. Only people having superior informa-

tion are supposed to join the Information Market and

to make profit by contributing their information. An-

other advantage is the continuous trading possibility.

As online Information Markets are fully automated

they operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. There-

fore, once a participant likes to reveal his information,

he can use the market at any time. A survey or Delphi

study represents only a snapshot in time compared to

an Information Market. Furthermore, IMs tackle sev-

eral challenges regarding common resistance against

business change. In general, every innovation can be

considered as a change project. Therefore, we discuss

challenges of change projects in the following section.

In change projects, several challenges exist in

enterprises and the business culture that may steer

innovation projects into trouble. (Jørgensen et al.,

2008) conducted a comprehensive survey among

1.500 practitioners worldwide in order to investigate

the reasons of project failures

1

.

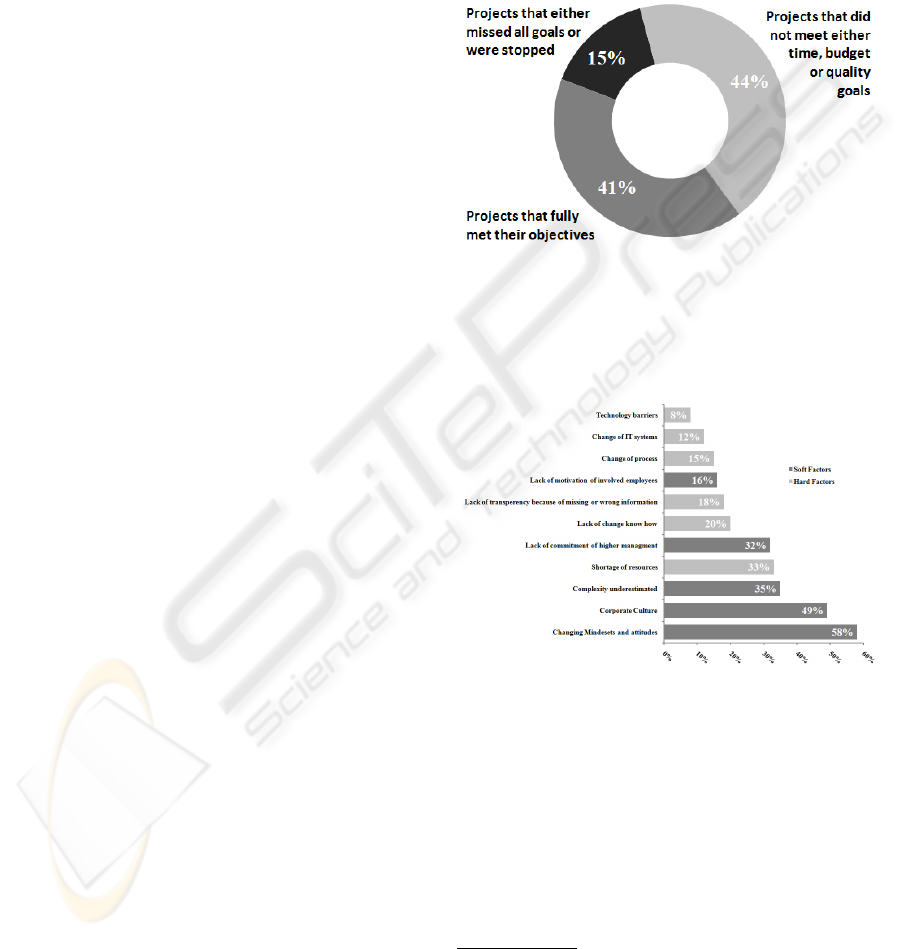

Figure 1 shows the results of the survey regard-

ing the project success rate in companies that project

leaders reported. Therefore, 59 % were somehow

troubled, whereas 15 % out of these missed their goals

or were stopped.

ticipants do not have to exhibit their complete knowl-

edge. Thus, participants use their information to gain

profits from stock trading and report their opinion in-

directly. Additionally, IMs have also a playful aspect.

Soukhoroukova and Spann successfully used IMs

for the assessment product innovation alternatives,

e.g. mp3 players (Soukhoroukova and Spann, 2005).

Compared to conjoint analysis and other methods,

IMs with 8-12 participants are more robust and re-

liable compared to conjoint analysis with 307 partic-

ipants. Spann emphasizes that IMs must have an ap-

propriate amount of traders to work well (Spann and

Skiera, 2004). But people do not want to trade if mar-

kets are thin. One way to add liquidity is the intro-

duction of Market Makers. In financial stock markets

like NYSE or NASDAQ Market Makers are common

in order to provide liquidity. Stathel et al. analyzed

the impact of automated market making in virtual IMs

(Stathel et al., 2009). In a field experiment for the

European Soccer Championship in 2008, the results

show a significant gain in liquidity through the usage

of automated market making.

IMs bear several advantages compared to other

methods for information aggregation like surveys or

nominal group techniques. As traders reveal their ex-

pectations via buying and selling shares representing

a future event, the trading success can be bound to

a performance based incentive system. The better

a participant trades in the market, the more he gets

compensated either with prizes or real money. Hence,

this powerful incentive mechanism motivates people

to stay active in the Information Market. Furthermore,

people in IMs are a subject to the so-called “self selec-

tion” process. Only people having superior informa-

tion are supposed to join the Information Market and

to make profit by contributing their information. An-

other advantage is the continuous trading possibility.

As online Information Markets are fully automated

they operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. There-

fore, once a participant likes to reveal his information,

he can use the market at any time. A survey or Delphi

study represents only a snapshot in time compared to

an Information Market. Furthermore, IMs tackle sev-

eral challenges regarding common resistance against

business change. In general, every innovation can be

considered as a change project. Therefore, we discuss

challenges of change projects in the following section.

In change projects, several challenges exist in

enterprises and the business culture that may steer

innovation projects into trouble. (Jørgensen et al.,

2008) conducted a comprehensive survey among

1.500 practitioners worldwide in order to investigate

the reasons of project failures

1

.

1

The survey covered 1.532 organizations of all sizes,

Figure 1 shows the results of the survey regard-

ing the project success rate in companies that project

leaders reported. Therefore, 59 % were somehow

troubled, whereas 15 % out of these missed their goals

or were stopped.

Figure 1: Success Rate in Change Projects.

This indicates that approximately 60 % of all

change projects can be improved in order to reduce

the fraction of troubled projects.

Figure 2: Success Rate in Change Projects.

In figure 2, the three major significant challenges

are the “changing mindset and attitudes” followed

by the “cooperate culture” and the “complexity of

projects”. One cannot rank all these challenges ac-

cording to their importance based on the numbers in

figure 2 which represent the frequency how often the

aspect was mentioned in the survey without relating

them to importance. There are three aspects men-

tioned in the survey which we like to address with

an EIM:

• Lack of higher management commitment (32 %)

• Lack of transparency because of missing or wrong

information (18 %)

• Lack of motivation of involved employees (16 %)

balanced around the globe and across industries. In total, 21

industries, whereby 14 % companies employed more than

100.000 employees and 22 % had less than 1.000 employ-

ees.

Figure 1: Success Rate in Change Projects.

This indicates that approximately 60 % of all

change projects can be improved in order to reduce

the fraction of troubled projects.

ticipants do not have to exhibit their complete knowl-

edge. Thus, participants use their information to gain

profits from stock trading and report their opinion in-

directly. Additionally, IMs have also a playful aspect.

Soukhoroukova and Spann successfully used IMs

for the assessment product innovation alternatives,

e.g. mp3 players (Soukhoroukova and Spann, 2005).

Compared to conjoint analysis and other methods,

IMs with 8-12 participants are more robust and re-

liable compared to conjoint analysis with 307 partic-

ipants. Spann emphasizes that IMs must have an ap-

propriate amount of traders to work well (Spann and

Skiera, 2004). But people do not want to trade if mar-

kets are thin. One way to add liquidity is the intro-

duction of Market Makers. In financial stock markets

like NYSE or NASDAQ Market Makers are common

in order to provide liquidity. Stathel et al. analyzed

the impact of automated market making in virtual IMs

(Stathel et al., 2009). In a field experiment for the

European Soccer Championship in 2008, the results

show a significant gain in liquidity through the usage

of automated market making.

IMs bear several advantages compared to other

methods for information aggregation like surveys or

nominal group techniques. As traders reveal their ex-

pectations via buying and selling shares representing

a future event, the trading success can be bound to

a performance based incentive system. The better

a participant trades in the market, the more he gets

compensated either with prizes or real money. Hence,

this powerful incentive mechanism motivates people

to stay active in the Information Market. Furthermore,

people in IMs are a subject to the so-called “self selec-

tion” process. Only people having superior informa-

tion are supposed to join the Information Market and

to make profit by contributing their information. An-

other advantage is the continuous trading possibility.

As online Information Markets are fully automated

they operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. There-

fore, once a participant likes to reveal his information,

he can use the market at any time. A survey or Delphi

study represents only a snapshot in time compared to

an Information Market. Furthermore, IMs tackle sev-

eral challenges regarding common resistance against

business change. In general, every innovation can be

considered as a change project. Therefore, we discuss

challenges of change projects in the following section.

In change projects, several challenges exist in

enterprises and the business culture that may steer

innovation projects into trouble. (Jørgensen et al.,

2008) conducted a comprehensive survey among

1.500 practitioners worldwide in order to investigate

the reasons of project failures

1

.

1

The survey covered 1.532 organizations of all sizes,

Figure 1 shows the results of the survey regard-

ing the project success rate in companies that project

leaders reported. Therefore, 59 % were somehow

troubled, whereas 15 % out of these missed their goals

or were stopped.

Figure 1: Success Rate in Change Projects.

This indicates that approximately 60 % of all

change projects can be improved in order to reduce

the fraction of troubled projects.

Figure 2: Success Rate in Change Projects.

In figure 2, the three major significant challenges

are the “changing mindset and attitudes” followed

by the “cooperate culture” and the “complexity of

projects”. One cannot rank all these challenges ac-

cording to their importance based on the numbers in

figure 2 which represent the frequency how often the

aspect was mentioned in the survey without relating

them to importance. There are three aspects men-

tioned in the survey which we like to address with

an EIM:

• Lack of higher management commitment (32 %)

• Lack of transparency because of missing or wrong

information (18 %)

• Lack of motivation of involved employees (16 %)

balanced around the globe and across industries. In total, 21

industries, whereby 14 % companies employed more than

100.000 employees and 22 % had less than 1.000 employ-

ees.

Figure 2: Success Rate in Change Projects.

In figure 2, the three major significant challenges

are the “changing mindset and attitudes” followed

by the “cooperate culture” and the “complexity of

projects”. One cannot rank all these challenges ac-

cording to their importance based on the numbers in

figure 2 which represent the frequency how often the

aspect was mentioned in the survey without relating

them to importance. There are three aspects men-

tioned in the survey which we like to address with

1

The survey covered 1.532 organizations of all sizes,

balanced around the globe and across industries. In total, 21

industries, whereby 14 % companies employed more than

100.000 employees and 22 % had less than 1.000 employ-

ees.

INNOVATION ASSESSMENT VIA ENTERPRISE INFORMATION MARKETS

207

an EIM:

• Lack of higher management commitment (32 %)

• Lack of transparency because of missing or wrong

information (18 %)

• Lack of motivation of involved employees (16 %)

In the following, we introduce the concept of

EIMs as a tool for innovation management which

we applied during an innovation cycle at EnBW

2

.

The EnBW is one of the biggest electricity suppliers

in Germany and conducts internal innovation work-

shops since 3 years. Employees were invited to de-

velop ideas and describe them in innovation project

proposals in order to improve their working environ-

ment. The two day workshop’s scope was exclusively

about IT-Services improving employees’ working en-

vironment. Having the workshop proposals consol-

idated, the remaining innovation project proposals

were traded for several weeks in an EIM by employ-

ees involved in the innovation workshop.

This paper is structured as follows, in the next

section, the EnBW Innovation Market will be intro-

duced, followed by an in depth description of the mar-

ket design and arrangements. In section 3, the field

experiment results are illustrated and related to the

challenges in innovation processes. The paper ends

with a conclusion summarizing the contribution of

this work.

2 THE ENBW INNOVATION

MARKET

In the following section, we present the results of the

EIM at EnBW. We introduce the EIM design before

we state research questions in order to illustrate the

results accordingly.

2.1 Experiment Design

The innovation workshop in March 2009 was held the

3

rd

time and the experience of the executives in doing

workshops for innovation topics is, that employees

are in general interested in contributing their knowl-

edge. The objective of the workshop is to have a mix-

ture of presentations about new technologies concern-

ing internal processes in order to activate the atten-

dants’ creativity of how they could use new technolo-

gies to make their own daily work more efficient.

On the 1

st

workshop day, attendees had been

given a comprehensive overview about interesting re-

cent technological developments. These technologies

2

http://www.enbw.com

Table 1: Products in the EIM.

Name

01. Twitterinfo

02. MEREGIO-Plattform

03. Heim-Automation

04. Parallele Dokumentenbearbeitung

05. Intelligente Terminplanung

06. Web 2.0 Plakate

07. Digitalisieren von Visitenkarten

08. xing@enbw.com

09. new contact networking

10. All in One

11. Ger

¨

ateinventar

12. mobile Z

¨

ahlererfassung

(ranging from interactive social technologies to de-

vices for power management) were identified by com-

pany representatives previous to the workshop. An

initial collection of technologies was gathered by an

agency and the 12 most interesting ones for the com-

pany were selected to be presented in the workshop

presentation slots.

On the 2

nd

day, attendees had the opportunity to

discuss their ideas in groups in order to develop and

improve them further. After every 30 minutes, groups

were mixed up so that everybody could talk with as

many different persons as possible. That guaranteed

the maximum of feedback to ones’ ideas. Finally,

attendees had the chance to submit their innovation

ideas. Altogether, 80 innovation proposals were sub-

mitted.

During the two days workshop the company no-

ticed that attendants were very interested in further

developing their ideas and therefore they supported

discussions with a company internal Wiki software.

Thus, attendees had the possibility to review and dis-

cuss their innovations. After 4 weeks of improvement

and discussion, 12 ideas were consolidated and ready

to be assessed via an EIM. In our experiment setting

we use one EIM for employees and one parallel EIM

limited to experts. Additionally we set up an expert

panel including decision makers. Table 1 gives an

overview of the 12 selected innovation alternatives.

The observation of the workshops in recent years

was that participants were very cooperative and in-

terested during the workshop, but there was no ade-

quate method and process to keep them in the innova-

tion context after the workshop. As innovation work-

shop participants were encouraged to join the EIM,

it should deliver evidence that employees can be ac-

tively engaged in the innovation process.

The EIM was available online from 2009/05/04

till 2009/06/12. Furthermore, compared to a regu-

INNOV 2010 - International Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT

208

lar financial exchange, the market was available 24

hours, 7 days a week. All in all, 110 people joined

the innovation workshop and everybody received an

anonymous account as well as a password to join the

EIM. The participants were supposed to trade virtual

stocks representing innovation alternatives (Table 1)

in order to rank them according to their personal ex-

pectation about the overall benefit for the company

via buying and selling shares. Each account was ini-

tially endowed with 100 shares of each stock and

100.000 virtual currency units. Therefore, partici-

pants were able to conveniently trade immediately in

each stock and did not have to buy an initial depot

by themselves. Additionally, an automated market

maker was constantly offering trading possibilities in

the EIM to ensure liquidity. The market maker mech-

anism was slightly adapted from the one Stathel et al.

used in their field experiment (Stathel et al., 2009).

The strategy of selling and buying shares depends

on the participant’s individual expectation of the at-

tractiveness of the underlying innovation. If they

thought that an innovation is overvalued compared to

another innovation alternative, which is in their mind

of minor attractiveness, they were supposed to sell

shares. Vice versa, if an innovation alternative is un-

dervalued in their opinion, they should have bought it

in order to raise the market price so that it represents

their expectations.

After the market was closed on the 2009/06/12, it

was expected that the stock prices represent the aggre-

gated valuation of all participants (Fama, 1970; Fama,

1991). Participants gave their private information in

the market via buying/selling orders while the mar-

ket mechanism aggregated all these. Once the mar-

ket was closed the innovations were ordered by their

market price and this ranking could be interpreted.

As a benchmark, opinions from decision makers and

an identical, parallel EIM for experts were taken in

order to evaluate if these expectations are congruent

with the EIM for employees. From decision makers,

a ranking was collected without having them traded

in a market to compare it against the market results.

Figure 3 summarizes the EIM experiment design.

EIM. The participants were supposed to trade virtual

stocks representing innovation alternatives (Table 1)

in order to rank them according to their personal ex-

pectation about the overall benefit for the company

via buying and selling shares. Each account was ini-

tially endowed with 100 shares of each stock and

100.000 virtual currency units. Therefore, partici-

pants were able to conveniently trade immediately in

each stock and did not have to buy an initial depot

by themselves. Additionally, an automated market

maker was constantly offering trading possibilities in

the EIM to ensure liquidity. The market maker mech-

anism was slightly adapted from the one Stathel et al.

used in their field experiment (Stathel et al., 2009).

The strategy of selling and buying shares depends

on the participant’s individual expectation of the at-

tractiveness of the underlying innovation. If they

thought that an innovation is overvalued compared to

another innovation alternative, which is in their mind

of minor attractiveness, they were supposed to sell

shares. Vice versa, if an innovation alternative is un-

dervalued in their opinion, they should have bought it

in order to raise the market price so that it represents

their expectations.

After the market was closed on the 2009/06/12, it

was expected that the stock prices represent the aggre-

gated valuation of all participants (Fama, 1970; Fama,

1991). Participants gave their private information in

the market via buying/selling orders while the mar-

ket mechanism aggregated all these. Once the mar-

ket was closed the innovations were ordered by their

market price and this ranking could be interpreted.

As a benchmark, opinions from decision makers and

an identical, parallel EIM for experts were taken in

order to evaluate if these expectations are congruent

with the EIM for employees. From decision makers,

a ranking was collected without having them traded

in a market to compare it against the market results.

Figure 3 summarizes the EIM experiment design.

Figure 3: Field Experiment Timeline.

2.2 User Interface

Figure 4 shows the start screen of the EIM. On the left

hand side, the navigation sidebar enables easy access

to the basic functionalities. It was visible at all times.

The content area (in the middle) shows a text explain-

ing the market goals. Traders, accessing the market

for the first time, were informed about the motivation

of the EnBW, why they run the EIM and what they ex-

pect from traders. Furthermore, it states that the two

best performing traders will be rewarded with prizes.

Figure 4: EIM Start Screen.

The content area changes depending on what

traders want to see. On the trading screen, traders

could submit their orders. They could also access

their depot screen or their transaction screen and so

on.

2.3 Research Questions

The main research question we like to investigate

within this work is:

How can we design Information Markets to

assess innovations in companies?

In order to get indications for that question, two

major objectives motivated the field experiment. The

first goal was to motivate participants using the

market system and to actively reveal their personal

(changing) expectations for a certain time period.

Traditionally, these expectations are being collected

via a questionnaire or expert groups. As these struc-

tured approaches are restrictive, the results are only

valid at one point in time. To get another evalua-

tion the questionnaire has to be repeated or the expert

Figure 3: Field Experiment Timeline.

2.2 User Interface

Figure 4 shows the start screen of the EIM. On the left

hand side, the navigation sidebar enables easy access

to the basic functionalities. It was visible at all times.

The content area (in the middle) shows a text explain-

ing the market goals. Traders, accessing the market

for the first time, were informed about the motivation

of the EnBW, why they run the EIM and what they ex-

pect from traders. Furthermore, it states that the two

best performing traders will be rewarded with prizes.

EIM. The participants were supposed to trade virtual

stocks representing innovation alternatives (Table 1)

in order to rank them according to their personal ex-

pectation about the overall benefit for the company

via buying and selling shares. Each account was ini-

tially endowed with 100 shares of each stock and

100.000 virtual currency units. Therefore, partici-

pants were able to conveniently trade immediately in

each stock and did not have to buy an initial depot

by themselves. Additionally, an automated market

maker was constantly offering trading possibilities in

the EIM to ensure liquidity. The market maker mech-

anism was slightly adapted from the one Stathel et al.

used in their field experiment (Stathel et al., 2009).

The strategy of selling and buying shares depends

on the participant’s individual expectation of the at-

tractiveness of the underlying innovation. If they

thought that an innovation is overvalued compared to

another innovation alternative, which is in their mind

of minor attractiveness, they were supposed to sell

shares. Vice versa, if an innovation alternative is un-

dervalued in their opinion, they should have bought it

in order to raise the market price so that it represents

their expectations.

After the market was closed on the 2009/06/12, it

was expected that the stock prices represent the aggre-

gated valuation of all participants (Fama, 1970; Fama,

1991). Participants gave their private information in

the market via buying/selling orders while the mar-

ket mechanism aggregated all these. Once the mar-

ket was closed the innovations were ordered by their

market price and this ranking could be interpreted.

As a benchmark, opinions from decision makers and

an identical, parallel EIM for experts were taken in

order to evaluate if these expectations are congruent

with the EIM for employees. From decision makers,

a ranking was collected without having them traded

in a market to compare it against the market results.

Figure 3 summarizes the EIM experiment design.

Figure 3: Field Experiment Timeline.

2.2 User Interface

Figure 4 shows the start screen of the EIM. On the left

hand side, the navigation sidebar enables easy access

to the basic functionalities. It was visible at all times.

The content area (in the middle) shows a text explain-

ing the market goals. Traders, accessing the market

for the first time, were informed about the motivation

of the EnBW, why they run the EIM and what they ex-

pect from traders. Furthermore, it states that the two

best performing traders will be rewarded with prizes.

Figure 4: EIM Start Screen.

The content area changes depending on what

traders want to see. On the trading screen, traders

could submit their orders. They could also access

their depot screen or their transaction screen and so

on.

2.3 Research Questions

The main research question we like to investigate

within this work is:

How can we design Information Markets to

assess innovations in companies?

In order to get indications for that question, two

major objectives motivated the field experiment. The

first goal was to motivate participants using the

market system and to actively reveal their personal

(changing) expectations for a certain time period.

Traditionally, these expectations are being collected

via a questionnaire or expert groups. As these struc-

tured approaches are restrictive, the results are only

valid at one point in time. To get another evalua-

tion the questionnaire has to be repeated or the expert

Figure 4: EIM Start Screen.

The content area changes depending on what traders

want to see. On the trading screen, traders could sub-

mit their orders. They could also access their depot

screen or their transaction screen and so on.

2.3 Research Questions

The main research question we like to investigate

within this work is:

How can we design Information Markets to

assess innovations in companies?

In order to get indications for that question, two

major objectives motivated the field experiment. The

first goal was to motivate participants using the

market system and to actively reveal their personal

(changing) expectations for a certain time period.

Traditionally, these expectations are being collected

via a questionnaire or expert groups. As these struc-

tured approaches are restrictive, the results are only

valid at one point in time. To get another evalua-

tion the questionnaire has to be repeated or the expert

INNOVATION ASSESSMENT VIA ENTERPRISE INFORMATION MARKETS

209

group has to meet again because expectations and be-

liefs change over time. By introducing an EIM, em-

ployees are able to reveal their expectations continu-

ously over a certain period.

On the other hand, motivating people to take part

in an IM is very important and only the first step to-

wards a successful method. It is equally fundamental

to harness the implicit knowledge of participants via

an appropriate IM design and incentive mechanism.

The aggregation of information in markets can only

work well, if implicit information can be extracted

and interpreted from traders. Results of both aspects

are analyzed in detail in section 3.

The main research question is therefore subdi-

vided into several research questions focusing on the

two aspects mentioned above. The following list

shows the subdivided research questions:

1. Are employees motivated using EIMs?

(a) How is the trading activity spread over time?

(b) How many traders are active during market du-

ration?

(c) How often do traders use the Innovation Mar-

ket?

(d) Will the Innovation Market be accepted by em-

ployees?

(e) How motivated are employees using Informa-

tion Markets?

2. How can implicit knowledge be harnessed?

(a) How do employees assess the method of Infor-

mation Markets?

(b) Do employees think that the EnBW is able to

assess innovations better with Information Mar-

kets?

(c) Do the results of the Information Markets and

the expert panel differ in innovation contexts?

Research question one and the relevant subdivided

questions are intended to indicate how traders are mo-

tivated during the market period. In innovation con-

texts, innovation cycles may last several months or

years. During that time, new information about the

innovation’s feasibility is very likely to occur. For ex-

ample, a technological breakthrough or unexpected

resources may make an innovation viable. In long

lasting Innovation Markets, new technological devel-

opments may be a motive for traders to change their

expectation about the innovations in the market. In

the end, their changed opinions are observable by dif-

ferent depot structures. The second research ques-

tion is also subdivided in several research questions.

These questions are intended to get an indication, how

employees estimate the overall benefit of an EIM.

3 EXPERIMENT RESULTS

As stated in section 2.3, the two main research ques-

tions are divided into two aspects “Motivating Em-

ployees” and “Harnessing implicit Information”. In

the following two subsections, the main results of

both aspects are discussed in detail.

3.1 Motivating Employees

In the following, the motivation of employees using

an EIM will be evaluated via two empirical aspects.

Firstly, the market activity of employees is analyzed

via their trading activity in the EIM (research ques-

tions 1 a-c). Secondly, survey results deliver evidence

for the assessment by employees and their motivation

in using the EIM (1 d-e).

3.1.1 Market Activity

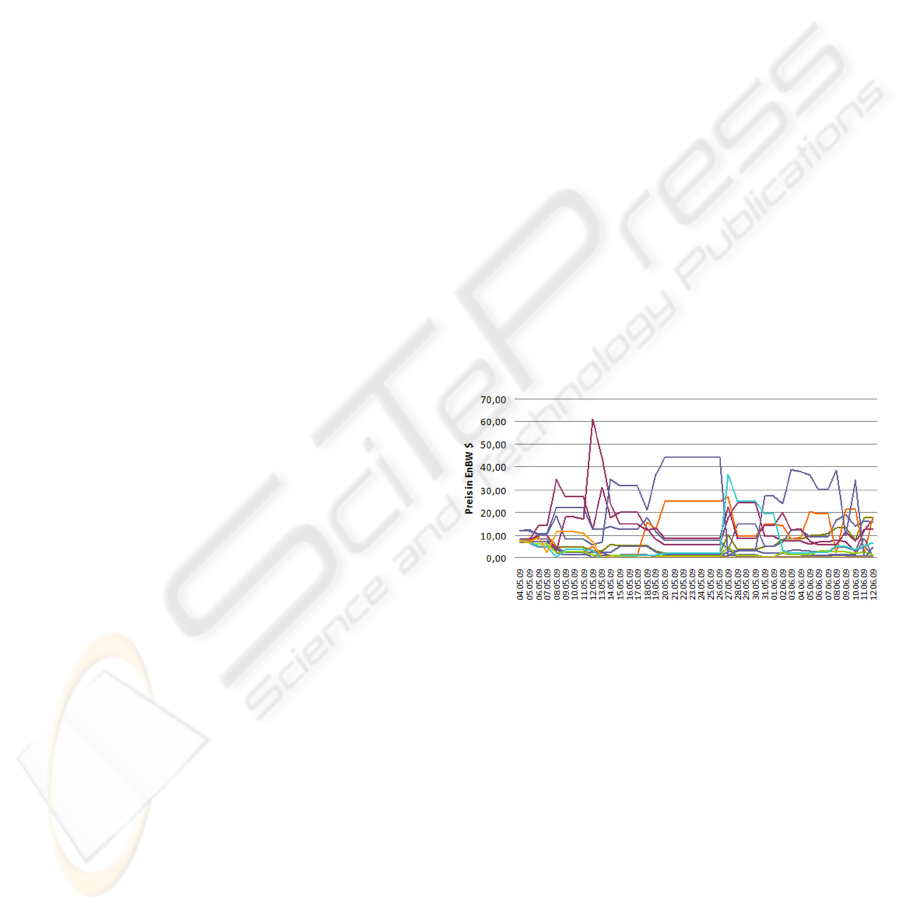

Figure 5 shows the stock price changes for each stock

over time. The stock prices for several products vary

heavily, which is an indication that trading activity

was intensive during the market period. Some stocks

were only sparely traded and were therefore of minor

attractiveness for traders.

group has to meet again because expectations and be-

liefs change over time. By introducing an EIM, em-

ployees are able to reveal their expectations continu-

ously over a certain period.

On the other hand, motivating people to take part

in an IM is very important and only the first step to-

wards a successful method. It is equally fundamental

to harness the implicit knowledge of participants via

an appropriate IM design and incentive mechanism.

The aggregation of information in markets can only

work well, if implicit information can be extracted

and interpreted from traders. Results of both aspects

are analyzed in detail in section 3.

The main research question is therefore subdi-

vided into several research questions focusing on the

two aspects mentioned above. The following list

shows the subdivided research questions:

1. Are employees motivated using EIMs?

(a) How is the trading activity spread over time?

(b) How many traders are active during market du-

ration?

(c) How often do traders use the Innovation Mar-

ket?

(d) Will the Innovation Market be accepted by em-

ployees?

(e) How motivated are employees using Informa-

tion Markets?

2. How can implicit knowledge be harnessed?

(a) How do employees assess the method of Infor-

mation Markets?

(b) Do employees think that the EnBW is able to

assess innovations better with Information Mar-

kets?

(c) Do the results of the Information Markets and

the expert panel differ in innovation contexts?

Research question one and the relevant subdivided

questions are intended to indicate how traders are mo-

tivated during the market period. In innovation con-

texts, innovation cycles may last several months or

years. During that time, new information about the

innovation’s feasibility is very likely to occur. For ex-

ample, a technological breakthrough or unexpected

resources may make an innovation viable. In long

lasting Innovation Markets, new technological devel-

opments may be a motive for traders to change their

expectation about the innovations in the market. In

the end, their changed opinions are observable by dif-

ferent depot structures. The second research ques-

tion is also subdivided in several research questions.

These questions are intended to get an indication, how

employees estimate the overall benefit of an EIM.

3 EXPERIMENT RESULTS

As stated in section 2.3, the two main research ques-

tions are divided into two aspects “Motivating Em-

ployees” and “Harnessing implicit Information”. In

the following two subsections, the main results of

both aspects are discussed in detail.

3.1 Motivating Employees

In the following, the motivation of employees using

an EIM will be evaluated via two empirical aspects.

Firstly, the market activity of employees is analyzed

via their trading activity in the EIM (research ques-

tions 1 a-c). Secondly, survey results deliver evidence

for the assessment by employees and their motivation

in using the EIM (1 d-e).

3.1.1 Market Activity

Figure 5 shows the stock price changes for each stock

over time. The stock prices for several products vary

heavily, which is an indication that trading activity

was intensive during the market period. Some stocks

were only sparely traded and were therefore of minor

attractiveness for traders.

Figure 5: EIM Stock Prices over Time.

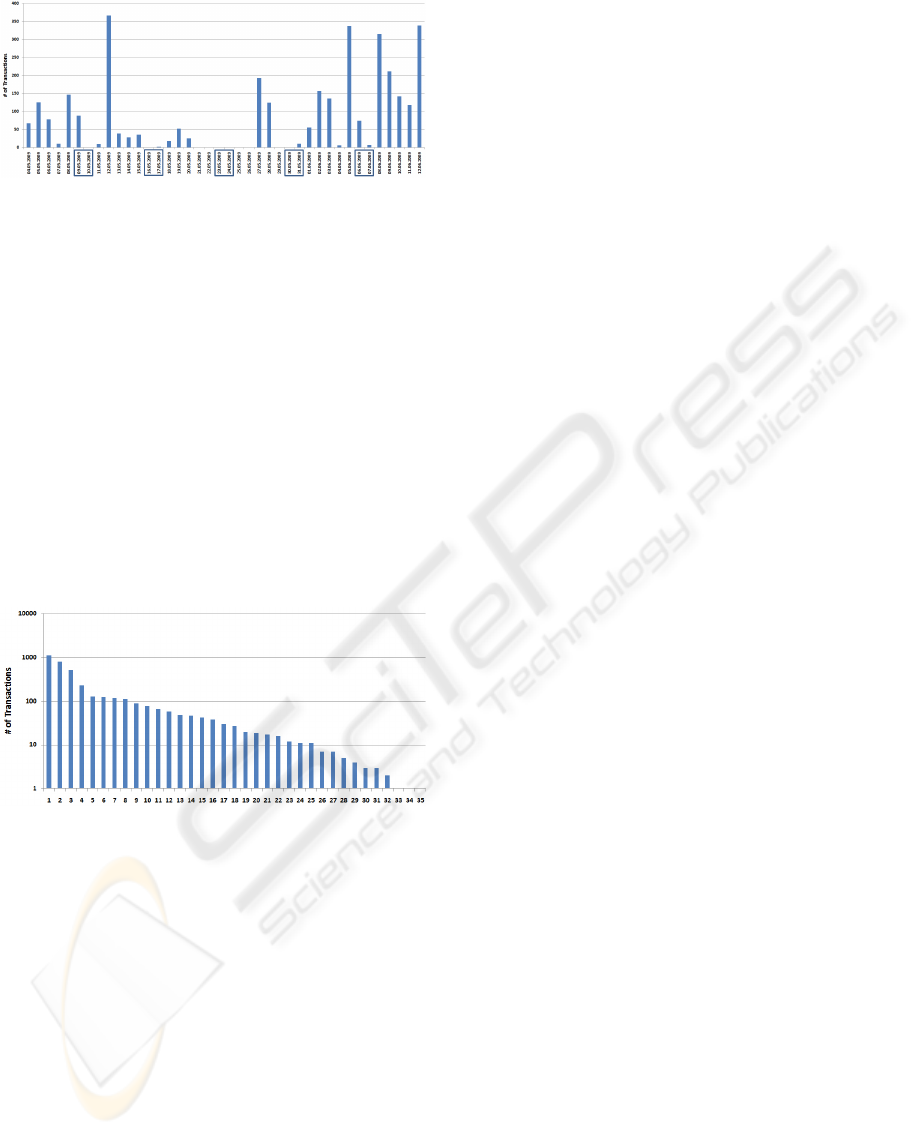

In order to further analyze the trading activity, fig-

ure 6 exhibits the trading activity on a daily average

basis of all transactions, where human traders were in-

volved. As stated in section 2.1, an automated market

maker mechanism was actively trading in the market

continuously providing traders with trading opportu-

nities. Hence, the market maker only reacts if a hu-

man trader submitted a matching BUY or SELL or-

der. Thus, the following figures focus on transactions

in which at least one human trader was involved, be-

cause the market maker could have traded with itself

to avoid several price effects. For further details, refer

to (Stathel et al., 2009).

One can see that between 05/20-05/25 no trans-

actions occurred. During that timespan, there was a

nationwide holiday and many employees took days

Figure 5: EIM Stock Prices over Time.

In order to further analyze the trading activity, fig-

ure 6 exhibits the trading activity on a daily average

basis of all transactions, where human traders were in-

volved. As stated in section 2.1, an automated market

maker mechanism was actively trading in the market

continuously providing traders with trading opportu-

nities. Hence, the market maker only reacts if a hu-

man trader submitted a matching BUY or SELL or-

der. Thus, the following figures focus on transactions

in which at least one human trader was involved, be-

cause the market maker could have traded with itself

to avoid several price effects. For further details, refer

to (Stathel et al., 2009).

One can see that between 05/20-05/25 no trans-

actions occurred. During that timespan, there was a

nationwide holiday and many employees took days

INNOV 2010 - International Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT

210

Figure 6: EIM Trading Activity over Time.

off. Besides this, overall trading activity was observ-

able, more or less every day. In total, trading occurred

on 30 out of 40 trading days including weekends.

Some traders remembered their user name and their

password and logged in during weekends, which was

not expected. In figure 6, the weekends are marked

with blue boxes. The daily trading average was 110

transactions with human involvement with a mini-

mum number of 2 and a maximum number of 366

transactions. In total, traders caused more than 2.000

transactions and submitted more than 4.000 orders.

Figure 7 shows the number of transactions per

trader. In total, the most active trader triggered

slightly more than 1000 transactions and the least ac-

tive trader did only one transaction.

Figure 7: Transactions per Trader.

The results in figure 6 and 7 indicate that research

questions 1a, 1b and 1c can be answered. Concerning

1a, the trading activity is spread over the whole mar-

ket period. That is exactly what one may expect be-

fore. The expectation, that the trading activity is only

observable at the beginning of the market period, can

be denied.

Research question 1b can be answered with 35

traders. In total, 110 workshop participants were in-

vited to join the market after the innovation workshop.

About one third followed the invitation and traded

in the market. Approximately 10 traders triggered

nearly 100 transactions, whereas 10 traders performed

less than 10. The rest resides somewhere between 100

and 10 transactions. That is also what one can expect

ex ante and is a typical distribution of trading behavior

reported in IM experiments (Luckner, 2008). Secon-

darily, figures 5, 6 and 7, show that traders used the

EIM nearly every day – even on weekends. On 30

out of 40 market days traders used the market, which

is quite more often than what one may expect. This

indicated that the motivation of traders does not de-

crease over time which is a very nice result regarding

research question 1c.

3.1.2 Survey Results for motivational Aspects

After the innovation workshop at EnBW, workshop

participants were asked by a paper based survey about

their opinion using an EIM at EnBW. The overall re-

sponse rate of the 110 participants was at 69 %, which

is representing. To indicate the related research ques-

tions 1d-e, we focus on two questions from the sur-

vey. One question was intended to get an estimate

about how employees approve the usage of an EIM.

They answered via a 5 point Likert scale where 5

represented “very good” whereas 1 represented “not

good”. On average, employees answered with 3.54, a

median of 4.00, a variance of 0.86 and a standard error

of 0.93. This indicates that the employees positively

judge the approach of using an EIM for innovation as-

sessment. This results supported by the high trading

activity presented in the previous section and the over-

all motivation of employees in using an EIM and indi-

cates, that employees approve the usage of EIM (Re-

search Question 1d). Furthermore, another question

asked about the employees’ motivation using an EIM.

Similarly, employees were expected to answer via a

5 point Likert scale where 5 represents “very high”

and 1 indicates “very low”. On average, employees

answered with 2.85 whereas the median was 3.00.

This indicates that the motivation using an EIM for a

longer time is perceived as neutral (research question

1e). Nevertheless, as results in section 3.1.1 indicate

a high motivation of employees and altogether, the re-

sults show evidence for the motivation of employees

in using an EIM.

3.2 Harnessing implicit Information

A very common way to measure the accuracy of IMs

is to compare its results to an observable benchmark.

In case of sport or political events, results of IMs can

be compared to the final values of the sport event

outcome or the final values of the election (Servan-

Schreiber et al., 2004; Berg et al., 2003; Luckner,

2008; Spann and Skiera, 2004; Stathel et al., 2009).

In case of EIM, a similar final value may exist, if

sales figures or project run times are traded. In case

of using EIM without real world events such as in-

novation assessment, IMs are nevertheless applicable

even if no final value is observable (Soukhoroukova,

2007; Chen et al., 2009). In case that no observable

Figure 6: EIM Trading Activity over Time.

off. Besides this, overall trading activity was observ-

able, more or less every day. In total, trading occurred

on 30 out of 40 trading days including weekends.

Some traders remembered their user name and their

password and logged in during weekends, which was

not expected. In figure 6, the weekends are marked

with blue boxes. The daily trading average was 110

transactions with human involvement with a mini-

mum number of 2 and a maximum number of 366

transactions. In total, traders caused more than 2.000

transactions and submitted more than 4.000 orders.

Figure 7 shows the number of transactions per

trader. In total, the most active trader triggered

slightly more than 1000 transactions and the least ac-

tive trader did only one transaction.

Figure 6: EIM Trading Activity over Time.

off. Besides this, overall trading activity was observ-

able, more or less every day. In total, trading occurred

on 30 out of 40 trading days including weekends.

Some traders remembered their user name and their

password and logged in during weekends, which was

not expected. In figure 6, the weekends are marked

with blue boxes. The daily trading average was 110

transactions with human involvement with a mini-

mum number of 2 and a maximum number of 366

transactions. In total, traders caused more than 2.000

transactions and submitted more than 4.000 orders.

Figure 7 shows the number of transactions per

trader. In total, the most active trader triggered

slightly more than 1000 transactions and the least ac-

tive trader did only one transaction.

Figure 7: Transactions per Trader.

The results in figure 6 and 7 indicate that research

questions 1a, 1b and 1c can be answered. Concerning

1a, the trading activity is spread over the whole mar-

ket period. That is exactly what one may expect be-

fore. The expectation, that the trading activity is only

observable at the beginning of the market period, can

be denied.

Research question 1b can be answered with 35

traders. In total, 110 workshop participants were in-

vited to join the market after the innovation workshop.

About one third followed the invitation and traded

in the market. Approximately 10 traders triggered

nearly 100 transactions, whereas 10 traders performed

less than 10. The rest resides somewhere between 100

and 10 transactions. That is also what one can expect

ex ante and is a typical distribution of trading behavior

reported in IM experiments (Luckner, 2008). Secon-

darily, figures 5, 6 and 7, show that traders used the

EIM nearly every day – even on weekends. On 30

out of 40 market days traders used the market, which

is quite more often than what one may expect. This

indicated that the motivation of traders does not de-

crease over time which is a very nice result regarding

research question 1c.

3.1.2 Survey Results for motivational Aspects

After the innovation workshop at EnBW, workshop

participants were asked by a paper based survey about

their opinion using an EIM at EnBW. The overall re-

sponse rate of the 110 participants was at 69 %, which

is representing. To indicate the related research ques-

tions 1d-e, we focus on two questions from the sur-

vey. One question was intended to get an estimate

about how employees approve the usage of an EIM.

They answered via a 5 point Likert scale where 5

represented “very good” whereas 1 represented “not

good”. On average, employees answered with 3.54, a

median of 4.00, a variance of 0.86 and a standard error

of 0.93. This indicates that the employees positively

judge the approach of using an EIM for innovation as-

sessment. This results supported by the high trading

activity presented in the previous section and the over-

all motivation of employees in using an EIM and indi-

cates, that employees approve the usage of EIM (Re-

search Question 1d). Furthermore, another question

asked about the employees’ motivation using an EIM.

Similarly, employees were expected to answer via a

5 point Likert scale where 5 represents “very high”

and 1 indicates “very low”. On average, employees

answered with 2.85 whereas the median was 3.00.

This indicates that the motivation using an EIM for a

longer time is perceived as neutral (research question

1e). Nevertheless, as results in section 3.1.1 indicate

a high motivation of employees and altogether, the re-

sults show evidence for the motivation of employees

in using an EIM.

3.2 Harnessing implicit Information

A very common way to measure the accuracy of IMs

is to compare its results to an observable benchmark.

In case of sport or political events, results of IMs can

be compared to the final values of the sport event

outcome or the final values of the election (Servan-

Schreiber et al., 2004; Berg et al., 2003; Luckner,

2008; Spann and Skiera, 2004; Stathel et al., 2009).

In case of EIM, a similar final value may exist, if

sales figures or project run times are traded. In case

of using EIM without real world events such as in-

novation assessment, IMs are nevertheless applicable

even if no final value is observable (Soukhoroukova,

2007; Chen et al., 2009). In case that no observable

Figure 7: Transactions per Trader.

The results in figure 6 and 7 indicate that research

questions 1a, 1b and 1c can be answered. Concerning

1a, the trading activity is spread over the whole mar-

ket period. That is exactly what one may expect be-

fore. The expectation, that the trading activity is only

observable at the beginning of the market period, can

be denied.

Research question 1b can be answered with 35

traders. In total, 110 workshop participants were in-

vited to join the market after the innovation workshop.

About one third followed the invitation and traded

in the market. Approximately 10 traders triggered

nearly 100 transactions, whereas 10 traders performed

less than 10. The rest resides somewhere between 100

and 10 transactions. That is also what one can expect

ex ante and is a typical distribution of trading behavior

reported in IM experiments (Luckner, 2008). Secon-

darily, figures 5, 6 and 7, show that traders used the

EIM nearly every day – even on weekends. On 30

out of 40 market days traders used the market, which

is quite more often than what one may expect. This

indicated that the motivation of traders does not de-

crease over time which is a very nice result regarding

research question 1c.

3.1.2 Survey Results for Motivational Aspects

After the innovation workshop at EnBW, workshop

participants were asked by a paper based survey about

their opinion using an EIM at EnBW. The overall re-

sponse rate of the 110 participants was at 69 %, which

is representing. To indicate the related research ques-

tions 1d-e, we focus on two questions from the sur-

vey. One question was intended to get an estimate

about how employees approve the usage of an EIM.

They answered via a 5 point Likert scale where 5

represented “very good” whereas 1 represented “not

good”. On average, employees answered with 3.54, a

median of 4.00, a variance of 0.86 and a standard error

of 0.93. This indicates that the employees positively

judge the approach of using an EIM for innovation as-

sessment. This results supported by the high trading

activity presented in the previous section and the over-

all motivation of employees in using an EIM and indi-

cates, that employees approve the usage of EIM (Re-

search Question 1d). Furthermore, another question

asked about the employees’ motivation using an EIM.

Similarly, employees were expected to answer via a

5 point Likert scale where 5 represents “very high”

and 1 indicates “very low”. On average, employees

answered with 2.85 whereas the median was 3.00.

This indicates that the motivation using an EIM for a

longer time is perceived as neutral (research question

1e). Nevertheless, as results in section 3.1.1 indicate

a high motivation of employees and altogether, the re-

sults show evidence for the motivation of employees

in using an EIM.

3.2 Harnessing Implicit Information

A very common way to measure the accuracy of IMs

is to compare its results to an observable benchmark.

In case of sport or political events, results of IMs can

be compared to the final values of the sport event

outcome or the final values of the election (Servan-

Schreiber et al., 2004; Berg et al., 2003; Luckner,

2008; Spann and Skiera, 2004; Stathel et al., 2009).

In case of EIM, a similar final value may exist, if

sales figures or project run times are traded. In case

of using EIM without real world events such as in-

novation assessment, IMs are nevertheless applicable

even if no final value is observable (Soukhoroukova,

INNOVATION ASSESSMENT VIA ENTERPRISE INFORMATION MARKETS

211

2007; Chen et al., 2009). In case that no observable

real world benchmark or event can be used to deter-

mine the accuracy of an EIM, other benchmarks are

needed. One option introduced by (Spann and Skiera,

2004)is to run two markets in parallel. Traders are

only allowed to participate in one market. If both

markets are closed, the final stock values of the first

market can be taken as a payout function for the sec-

ond market and vice versa. Other approaches are re-

ported by Slamka or Chen by using the final stock

price as payout function (Slamka, 2009; Chen et al.,

2009). It is doubtful to use the last transaction price

as a benchmark because the payout function has to be

transparent to traders in EIM and therefore strategic

behavior is beneficial for traders. Traders may tend to

steer their favored stocks as they like the market re-

sult should be and that is not what should be fostered.

The payout function should lead traders to reveal their

real expectations based on the goal the market should

fulfill. The payout function should be the dominant

guideline that strategic behavior is neither rewarded

nor incentivized. Therefore, we designed the payout

function that the outcomes of the EIM for employees

were weighted 1/3 and the results of the EIM for ex-

perts were weighted 2/3. The market for experts were

not accessible for employees and vice versa. The in-

tention was to motivate employees to reveal their true

expectation because they did not know what the re-

sults of the expert market would be. Therefore, they

had no incentive to play the market and traded their

true expectation in order to align to the expert market

in order to make a profit.

For the field experiment at EnBW, two bench-

marks were intended to be compared to the results of

the EIM for employees. The first one was an identical

market running in parallel. Dedicated experts chosen

from EnBW and also presenters of the slots during the

innovation workshop were supposed to use the expert

market. These experts were employees mostly from

external companies affiliated with the EnBW. In to-

tal, 8 experts were supposed to participate in the ex-

pert market. Unfortunately, only 7 transaction were

observed in the market so the result cannot serve as

a benchmark. The reason for this was that the ex-

perts were not originally employees of the EnBW and

therefore had no interest or not sufficient information

to trade in the expert market. Regrettably, the results

from the expert market must be discarded.

The second benchmark was the comparison to a

ranking created by decision makers for innovation

processes at EnBW. In the past, the innovation work-

shop was conducted twice and every time the decision

makers came to their decision which innovation will

be implemented by themselves. In 2009, the EIM was

an additional method to get further information from

employees which was a rather new situation even for

decision makers. In the next section, the interaction

between the EIM and decision makers will be illus-

trated.

3.2.1 Expert Expectations and Information

Markets

After the market closed, we payed traders according

to their depot structure and the weighting against the

expert market. Due to the fact that the expert mar-

ket collapsed, the weighting had only minor influence

and did not changed the ranking from the EIM for em-

ployees. Therefore, only the results for the EIM for

employees can be benchmarked against the results of

decision makers. All things considered, there are four

imaginable outcomes of the two benchmarks which

are described in table 2.

Table 2: Possible Outcomes.

EIM

positive negative

Decision

Makers

positive good (1) action required (2)

negative action required (3) good (4)

In the first case (1), market participants as well

as the experts (decision makers) come to the same

or similar innovation ranking. This indicates that the

majority of people involved in innovation processes

think the same way about the most promising inno-

vation. In the second (2) and the third (3) case, either

the experts or the market points in different directions.

For the company, this is an indication that at least one

group think different about the innovations, but it is

left clear, who is right. But in innovation contexts, one

cannot state that the one innovation is right and the

other is not ex ante. Therefore, the indication in case

one is mostly desirable, because the decision makers

in the company may have a suggestion, which innova-

tion they should support by themselves. And if both,

the market and the experts, point in the same direction

the decision to make is easier to assert. In the second

and third case, it is of high importance, that before the

final decision is made the decision makers check the

innovation again, eventually through another control

group like external consultants or internal counselors.

The different direction of the market and the experts

opinions are a valid sign to do so. In the worst (4)

case, the market as well as the experts point to the

same direction, but both groups may have a differ-

ent perception about the innovations compared what

is the right decision. If the decision makers haven’t

such markets, they must decide which innovation they

should go for. Either way, the combination of experts

INNOV 2010 - International Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT

212

and IMs is a way to have the possibility to get more

opinions from groups with different point of view –

and that is what is very important in innovation con-

texts. In case 2 and 3 this indication may be a valuable

hint to rethink an innovation. Through the self selec-

tion process, only employees with relevant knowledge

are supposed and expected to join the market. One

trader may have information about the customer or

business partners needs and makes his decision about

an innovation based on that information. Another

employee maybe has another business network and

therefore can input that information into the market.

All in all, for the company there is no disadvantage

having an additional information source which inno-

vation the employees prefer. Moreover, they have an

additional control group to experts or consultants in

order to identify the most beneficial innovation.

In case that the market and the experts have the

same expectation about the innovations, it may hap-

pen that the decision makers have a different one.

That is expressed in the table 2 by (negative/negative).

But it cannot be determined ex ante, in which sector

in table 2 the results are, because sector 1 and 4, as

well as 2 and 3 are possible, depending if the results

from decision makers can be assumed as positive or

negative, which is not possible ex ante – and not pos-

sible ex post too. Ex post, it is not feasible to check

if the results of a “wrong” results turn out to be right,

because not all innovations can be implemented and

checked for success. Even if an innovation may be

the best one and is lower ranked from the “positive”-

labeled, it may be the best one. But that cannot

be proved until all innovations are implemented and

evaluated against each other. As already pointed out,

there is no disadvantage having sophisticated infor-

mation about the employees’ expectation via markets

and experts additionally. Either way, it helps to avoid

implementing a barely advantageous innovation – but

not necessarily. Besides the effect, that employees are

integrated in decision making, which has relevance

for the business culture, the EnBW noticed two major

benefits of having the EIM for employees in addition

to expert opinions:

1. Additional ranking of innovations

2. Information from a group of employees

3.2.2 Survey Results for Harnessing Implicit

Information

In table 3, the combined prices of the EIM and the

EIM for experts are displayed. The combined price

is the combination of the weighted EIM prices (1/3)

and the EIM for experts (2/3). As described before,

the EIM will be compared to the ranking by decision

makers. Unfortunately, the expert market only gen-

erated 7 transaction, which is not usable as a bench-

mark. As one can easily see, the results of the ex-

pert market did not change the overall ranking in the

combination of the total payout prices. Therefore, the

payout was realized with the weighting, although the

expert market was illiquid.

Furthermore, table 3 shows the ranked results

from decision makers. The horizontal line divides the

top 5 stocks in the EIM because the final values were

above the issued price of 8.33 currency units. There-

fore, it can be assumed that these 5 innovation pro-

posals are favored by employees. Interestingly, the

top three innovations from decision makers were also

under the top four innovations in the EIM which in-

dicate that in this field experiment the result from the

EIM differs only slightly from the decision makers

(research question 2c). This is a strong indication that

decision makers as well as employees in the EIM have

the same expectation, although they were separated

during the runtime of the EIM.

In this context we also asked employees after the

innovation workshop with 110 participants about their

assessment, if the EnBW will be able to better assess

innovations via EIM than traditional methods prior to

the experiment after a tutorial and and introduction to

EIMs. In total, 68 participants answered that ques-

tion. The 5 point Likert scaled question (5 “strong

agreement”, 1 “no agreement”) was answered with an

average of 3.19 and a median of 3.00. The variance

was 0.86 and the standard deviation was 0.93. One

can see that the overall opinion of employees with an

average of 3.19 is positive, that most of them believe

that the approach of using EIM is beneficial for the

company. The variance as well as the standard er-

ror and especially the median indicate that the results

do vary slightly and the majority of the respondents

consider that a company can assess innovations with

EIM. This indicates that research question 2b can be

answered positively. That result is not surprising, be-

cause the employees can be integrated in innovation

processes via EIM. For employees, it is a simple par-

ticipative way to make their information available to

executives and decision makers anonymously. One

problem in companies with strict, top down hierar-

chies is, that employees think they do have no im-

pact on decisions and the executives make their deci-

sions independent of the employees opinions. It is not

feasible to ask each employee about his opinion, but

with EIM, interested employees can join the market

and offer their information whereas the market mech-

anism aggregates each individual information effec-

tively. Moreover, that is also a benefit for decision

makers and executives.

INNOVATION ASSESSMENT VIA ENTERPRISE INFORMATION MARKETS

213

Table 3: Combined Prices and Decision Makers Ranking.

Name Combined Price Expert Market EIM Decision Makers Ranking

All in One 17,13 7,50 36,40 3

MEREGIO-Plattform 12,58 7,90 21,94 8

Web 2.0 Plakate 11,64 8,34 18,24 1

xing@enbw.com 10,92 8,34 16,07 2

Parallele Dokumentenbearbeitung 9,25 8,34 11,08 7

Geraeteinventar 7,56 8,34 6,00 11

mobile Zaehlererfassung 7,54 8,34 5,93 6

Heim-Automation 6,32 8,34 2,28 9

new contact networking 6,10 8,34 1,62 12

Intelligente Terminplanung 5,85 8,34 0,86 4

Digitalisieren von Visitenkarten 5,83 8,34 0,81 10

Twitterinfo 5,72 8,34 0,49 5

In the next survey question, the workshop partic-

ipants were asked, what their opinion about the ap-

proach of using EIM to assess innovations is. The

question was how they assess the method of EIM for

the assessment of innovations. In total, 67 partici-

pants answered that question with an average of 3.54

and a median of 4.00. The variance is 0.86 and the

standard error is 0.93. This indicates that the em-

ployees judge the approach of using EIM for inno-

vation assessment as a good one concerning research

question 2a. The 5 point Likert scale ranged from 5

“very good” till 1 “not good”. This fosters the results

from the question before (2b). Both results do show a

positive correlation of 0.566, which indicated that the

EnBW is able to assess innovations better with EIM

from an employees view. Furthermore, the correlation

is significant at the 5 % level. In general, participants

consider EIM as a good method for innovation assess-

ment. Concerning research question 2b, the overall

results indicate that employees are sure that EnBW is

able to evaluate innovations with EIM.

4 CONCLUSIONS

This paper shows that Enterprise Information Markets

motivate employees to take part in innovation pro-

cesses. Furthermore the field experiment at EnBW

achieved continuous participation during the market

period. Market participants approved the method of

EIM and used it more often than one may have ex-

pected. Moreover, the results show that the assess-

ment of the EIM and the expert panel overlap in the

top 3 innovations, which indicates that in this field ex-

periment the results differ only slightly regarding the

ranking of the innovations. The situation could have

been different, if the market results differed signifi-

cantly from the results of the expert panel and hit case

(2) or (3) in table 2. Then, the decision makers have

to take further activities like hiring an external con-

sultant or involve other people capable of giving an

independent ranking. Another management decision

could be to invite so-called Lead Users to an expert

round and discuss their trading motives and further

elaborate on the underlying information. Lead user

analysis is a way to identify users in markets hav-

ing superior information (Spann et al., 2009). The

analysis can be based on market activity as well as

market success of single a user. A lead user analysis

was also conducted, which is not discussed in this pa-

per in detail due to page limitations. After the EIM

closed, the market results were verified in an expert

panel which finally decided to implement two inno-

vations in 2009. The implementation of “Web 2.0

Plakate” was finished within the second half of the

year 2009. “xing@enbw.com” won one out of three

so-called “Innovationsgutschein” worth 25.000ein an

internal award procedure and is going to be imple-

mented shortly. In total, 10 innovations contenders

applied for the three coupons. Therefore, the results

of the market supported the results of decision makers

strongly.

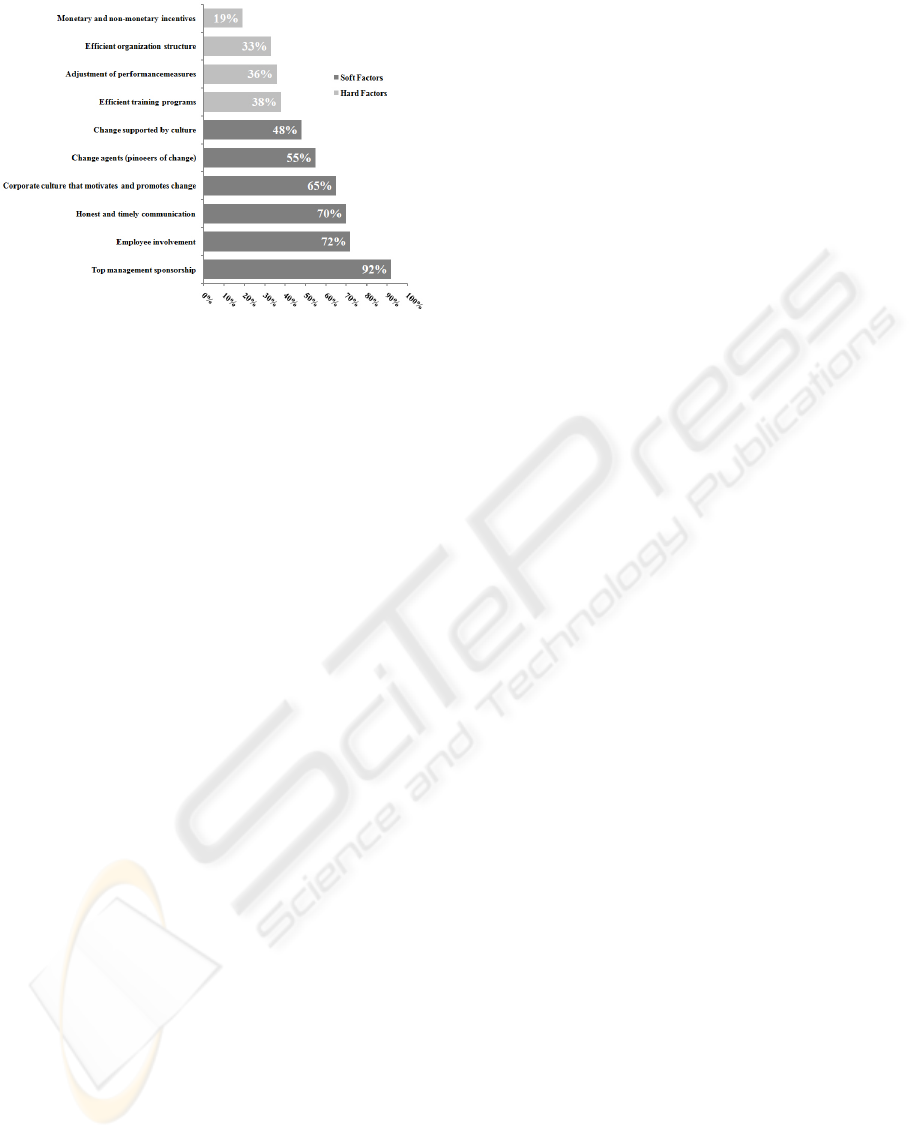

Figure 8 shows, which success factors are most

relevant for change management (Jørgensen et al.,

2008)

3

. The three top categories are also addressed

with the market. Interestingly, the top aspect is the

sponsorship by the top management. During our ex-

tensive analysis, some executives in the EIM were

identified as lead users. If the top management is also

involved in innovation processes as lead users, this

can be interpreted as a very strong sponsorship and

shows top management commitment.

The second success factor, “Employee involve-

ment”, is also addressed with an EIM. Employees

were invited to join the market, if they were interested

3

http://www-935.ibm.com/services/uk/gbs/pdf/making-

change-work.pdf, 2010/03/10

INNOV 2010 - International Multi-Conference on Innovative Developments in ICT

214

Figure 8: Success Factors of Change Management.

Employees took part in the market following the self

selection mechanism and if an employee did not want

to join the market, he was not forced to. Furthermore,

honest and timely communication is another essen-

tial success factor in change management. The mar-

ket can also be considered as communication method,

because employees can communicate even “negative”

information via the market mechanism. Often, em-

ployees do not communicate because they fear conse-

quences from their managers, if they announce nega-

tive information. In EIM, every employee is anony-

mous and may fearlessly communicate even nega-

tive information. Often, the success of change pro-

cesses are directly connected to the company culture

(Corsten et al., 2006). EnBW uses EIM in order to

involve employees actively, which indicates a very

open company culture. Often, employees cannot be

involved in innovation process due to complexity as-

pects in managing thousands of employees via ques-

tionnaires or online surveys. Information Markets are

a very scalable method to involve a large number of

employees efficiently and at low costs once the market

system is implemented (Spann and Skiera, 2004). The

market mechanism aggregates new information con-

tinuously and people participate autonomously, hence

motivating and involving employees to participate in

innovation processes. All in all, for the EnBW the

EIM was a new way to communicate with their em-

ployees in innovation processes and it provides a sus-

tainable method for long involvement after the inno-

vation workshop. Due to the success in 2009, the

EnBW likes to run another EIM in 2010. The very

valuable knowledge of employees is now a key main

pillar in their innovation process and therefore the

next EIM will be successful and confirm the results

presented in this paper.

REFERENCES

Berg, J., Nelson, F., and Rietz, T. (2003). Accuracy and

forecast standard error of prediction markets. Work-

ing paper, Departments of Accounting, Economy and

Finance, University of Iowa.

Chen, L., Goes, P., Harris, W., Marsden, J., and Zhang, J.

(2009). Preference Markets for Innovation Ranking

and Selection. Interfaces.

Christensen, C. and Raynor, M. (2003). The innovator’s

solution: Creating and sustaining successful growth.

Harvard Business School Press.

Corsten, H., G

¨

ossinger, R., and Schneider, H. (2006).

Grundlagen des Innovationsmanagements. Vahlen.

Fama, E. F. (1970). Efficient capital markets: A review of

theory and empirical work. The Journal of Finance,

25:383–417.

Fama, E. F. (1991). Efficient capital markets: Ii. The Jour-

nal of Finance, 46(5):1575–1617.

Green, K., Armstrong, J., and Graefe, A. (2007). Methods

to elicit forecasts from groups: Delphi and prediction

markets compared. Foresight: The International Jour-

nal of Applied Forecasting, 8:17–20.