MIKROW

An Intra-enterprise Semantic Microblogging Tool

as a Micro-knowledge Management Solution

Guillermo

´

Alvaro, Carmen C

´

ordoba, V

´

ıctor Penela, Michelangelo Castagnone

Francesco Carbone, Jos

´

e Manuel G

´

omez-P

´

erez and Jes

´

us Contreras

iSOCO, Avda. del Parten

´

on 16-18, 1-7, Madrid, Spain

Keywords:

Microblogging, Enterprise 2.0, Semantic web.

Abstract:

One of the biggest bottlenecks in Knowledge Management systems where end-users are supposed to actively

participate is precisely the hurdles they encounter that discourage them for keeping involved. On the other

hand, the so-called Web 2.0, where users participate in an active manner, willingly generating new content,

has been adopted by companies for their internal processes in the so-called Enterprise 2.0. In particular, mi-

croblogging systems have been embraced as a way of fostering internal communication within the enterprise

boundaries. In this paper, we propose a lightweight framework for Knowledge Management based on the

microblogging paradigm, and supported by the use of semantics, both internally with the use of domain on-

tologies, and externally by leveraging the Linked Data paradigm. A current implementation and evaluation

are also discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Knowledge Management (KM) within enterprises is

a discipline that comprises a set of techniques and

processes which pursue the following objectives: i)

identify, gather and organize the existing knowledge

within the enterprise, ii) facilitate the creation of new

knowledge, and iii) foster innovation in the company

through the reuse and support of workers’ abilities.

Arguably, there is already a wide range of tools

in the market that address and support KM processes

within enterprises. However, in most of the cases, the

potential of those tools gets compromised by an ex-

cessive complexity that prevents end-users from get-

ting deeply involved with the system. This leads to

end-users not following the protocols, and eventually

to a loss of the knowledge that the tools are supposed

to capture. Additionally, the integration of complex

KM systems within the infrastructures of large orga-

nizations is both effort and time-consuming.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, one can find

the Web 2.0 paradigm, where end-user involvement

is fostered through lightweight and easy-to-use tools.

These techniques are increasingly penetrating into the

context of enterprise solutions, in a paradigm usually

referred to as Enterprise 2.0. In particular, the trend

of microblogging -of which Twitter

1

is the most

prominent example- based on short messages and the

asymmetry of its social connections, has been em-

braced by a large number of companies as the per-

fect way of easily allowing its workers communicate

and actively participate in the community, as demon-

strated by successful examples like Yammer

2

, which

has implemented its microblogging enterprise solu-

tion into more than 70.000 organizations.

Our proposal is to apply the Web 2.0 principles

and in particular the microblogging approach to the

Knowledge Management processes, hence creating

an easy-to-use tool that wouldn’t prevent users from

using it. One of the main characteristics of the pro-

posal is its external simplicity -the only input param-

eter from the end-user would be used both for cap-

turing his experience and for retrieving suggestions

from the system-, though it is supported by complex

processes underneath. In fact, our contribution is en-

riched by semantics, though hidden to the users, in or-

der to support the Knowledge Management processes.

Firstly, internally the system is supported by a domain

ontology related to the particular enterprise, which

can capture the different concepts relating to the com-

1

http://www.twitter.com

2

http://www.yammer.com

36

Álvaro G., Córdoba C., Penela V., Castagnone M., Carbone F., Gómez-Pérez J. and Contreras J..

MIKROW - An Intra-enterprise Semantic Microblogging Tool as a Micro-knowledge Management Solution.

DOI: 10.5220/0003096000360043

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2010), pages 36-43

ISBN: 978-989-8425-30-0

Copyright

c

2010 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

pany knowledge, and secondly, externally by making

use of Linked Data resources available on the Web.

This paper is structured in three main sections: we

describe the State of the Art regarding Knowledge

Management and Microblogging in 2, we introduce

our theoretical contribution in 3 and finally we cover

implementation details and evaluation results in 4.

2 STATE OF THE ART

2.1 Knowledge Management

The value of Knowledge Management relates directly

to the effectiveness(Bellinger, 1996) with which the

managed knowledge enables the members of the or-

ganization to deal with today’s situations and effec-

tively envision and create their future. Because of the

new features of the market like the increasing avail-

ability and mobility of skilled workers, the growth of

the venture capital market, external options for ideas

sitting on the shelf, and the increasing capability of

external suppliers, knowledge is not anymore propri-

etary to the company. It resides in employees, sup-

pliers, customers, competitors, and universities. If

companies do not use the knowledge they have inside,

someone else will.

In recent years computer science has faced more

and more complex problems related to information

creation and fruition. Applications in which small

groups of users publish static information or per-

form complex tasks in a closed system are not scal-

able and nowadays are out of date. In 2004, James

Surowiecki introduced the concept of “The Wisdom

of Crowds”(Surowiecki et al., 2007) demonstrating

how complex problems can be solved more effec-

tively by groups operating according to specific con-

ditions, than by any individual of the group. The

collaborative paradigm leads to the generation of

large amounts of content and when a critical mass

of documents is reached, information becomes un-

available. Knowledge and information management

are not scalable unless formalisms are adopted. Se-

mantic Webs aim is to transform human readable con-

tent into machine readable(Fensel et al., 2003). With

this goal data interchange formats (e.g. RDF/XML,

N3, Turtle, N-Triples), and languages such as RDF

Schema (RDFS) and the Web Ontology Language

(OWL) have been defined.

The term “Computer Supported Cooperative

Work” (CSCW) was defined by Grief and Cash-

man(Grudin, 1994) in 1984 to designate the discipline

whose aim is the study of the influence of technol-

ogy on work. Over the years, CSCW researchers have

identified a number of basic dimensions of collabora-

tive work:

• Awareness. People working together should be

able to produce a certain level of shared knowl-

edge about the activities of others(Patterson et al.,

1990).

• Articulation Work. People who cooperated in

some way must be able to divide the work into

units and dividing them among themselves and

finally rebuilding them(Greenberg and Marwood,

1994)(Nardi et al., 2000).

• Appropriation or Tailorability. Technol-

ogy can be adapted as needed in a particu-

lar situation(Hughes et al., 1992)(Tang et al.,

1994)(Neuwirth et al., 1990).

A common problem with existing platforms

is their limited ability to “capture knowl-

edge”(Davenport, 2005): the channels are not

accessible to all and platforms do not allow interac-

tion and only store the final result of a process that

has required collaboration and exchange knowledge.

Computer supported collaborative work research

analyzed the introduction of Web 2.0 in corporations:

McAfee(McAfee, 2006) called “Enterprise 2.0”, a

paradigm shift in corporations towards the 2.0 philos-

ophy: collaborative work should not be based in the

hierarchical structure of the organization but should

follow the Web 2.0 principles of open collaboration.

This is especially true for innovation processes which

can be particularly benefited by the new open innova-

tion paradigm(Chesbrough et al., 2006). In a world

of widely distributed knowledge, companies do not

have to rely entirely on their own research, but should

open the innovation to all the employees of the orga-

nization, to providers and customers.

In a scenario in which collaborative work is not

supported and members of the community can barely

interact with others, solutions to everyday problems

and organizational issues rely on individual initia-

tive. Innovation and R&D management are complex

processes for which collaboration and communica-

tion are fundamental. They imply creation, recog-

nition and articulation of opportunities, which need

to be evolved into a business proposition in a second

stage. The duration of these tasks can be drastically

shortened if ideas come not just from the R&D de-

partment. This is the basis of the open innovation

paradigm which opens up the classical funnel to en-

compass flows of technology and ideas within and

outside the organization. Ideas are pushed in and out

the funnel until just a few reach the stage of commer-

cialization.

Technologies are needed to support the opening of

MIKROW

- An Intra-enterprise Semantic Microblogging Tool as a Micro-knowledge Management Solution

37

the innovation funnel, to foster interaction for the cre-

ation of ideas (or patents) and to push them through

and inside/outside the funnel. In a Web 2.0 environ-

ment, it is easier to edit and create content, collabo-

ration provides automatic filtering and every member

has a simple way to track proposals evaluation. Mi-

croblogging model covers the dimensions identified

in CSCW, is accessible to all employees, and records

all interactions fostering collaboration.

Figure 1: Open innovation funnel.

Web 2.0 tools do not have formal models that al-

low the creation of complex systems managing large

amounts of data. Nowadays solutions like folk-

sonomies (folks taxonomies), collaborative tagging

and social tagging are adopted for collaborative cat-

egorization of contents. In this scenario we have

to face the problem of scalability and interoperabil-

ity(Graves, 2007): making users free to use any

keyword is very powerful but this approach does

not consider the natural semantic relations between

the tags. Semantic Web can contribute introducing

computer-readable representations for simple frag-

ments of meaning. As we will see, an ontology-based

analysis of a plain text provides a semantic contextu-

alization of the content, supports tasks such as finding

semantic distance between contents and helps in cre-

ating relations between people with shared knowledge

and interests.

Moreover, a reward system is necessary to involve

people in the innovation process. Money is not a sole

motivating factor. There may be other factors such

as prestige and ego. A company could collaborate in

another firms innovation process as a marketing strat-

egy, in order to have a public recognition as an “inno-

vative partner”. Technology has to support the inno-

vation process in this aspect as well, helping decision

makers in the enterprise to evaluate the ideas and to

reward the members of the community.

2.2 Microblogging

Microblogging is one of the recent social phenom-

ena of Web 2.0, being one of the key concepts that

has brought Social Web to more than merely early

adopters and tech savvy users. The simplest definition

of microblogging, a lite version of blogging where

messages are restricted to less than a small number

of characters, does not make true judgment of the real

implications of this apparently constraint. Its simplic-

ity and ubiquitous usage possibilities have made mi-

croblogging one of the new standards in social com-

munication.

Although several microblogging networks have

been built, Twitter is currently and by far the most ex-

tended, counting more than 100 million users in April

of 2010. With its ease of use and the countless num-

ber of mobile and desktop applications built over its

API, Twitter has been able to grow from a mere tool

to a key way of communication.

One of Twitter’s key strategies has been its public

by default attitude in terms of tweets and basic user

information. This approach, although quite interest-

ing from a social point of view, rises several issues

in terms of privacy (Humphreys et al., 2010), partic-

ularly in a work related environment where most of

the information could be highly confidential: sharing

company information in a public social network could

lead to unintended leaks, misappropiation of internal

know-how and problems with property rights.

Obviously, where users go, companies follow, so

it was just a matter of time for companies to start

joining the global conversation to keep up with user’s

comments, opinions and with new trends, trying to be

leaders and not simply followers. A recent study from

Burson-Marsteller

3

shows that about 80% of current

Fortune 50 companies have an online presence in dif-

ferent social networks, being Twitter probably the one

where their presence is more important -65% of the

overall Fortune companies according to the study- and

more relevant -different accounts for different pur-

poses with direct interaction with customers.

While this approach mainly tries to leverage ex-

ternal information related to the company, internal

knowledge could be even more important for a com-

pany: what their employees know, which are their

opinions on company issues,. . . Yammer enters the

microblogging scene as the first social network with

a clear enterprise orientation. Its products, as simple

as Twitter high level design could be (status updates

as plain text), has reached a huge success counting

more than 70.000 companies from all kind of sizes

and fields as their clients. However, Yammer does not

really offer more than a simple evolution from cur-

rent chat tools, evolving into a Web 2.0 approach, not

providing with any of the benefits of the knowledge

management sciences, thus relying only in syntactic

analysis.

3

http://www.burson-marsteller.com/

KMIS 2010 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

38

3 AN INTRA-ENTERPRISE

SEMANTIC MICROBLOGGING

TOOL AS A

MICRO-KNOWLEDGE

MANAGEMENT SOLUTION

In this section, we describe our theoretical contribu-

tion towards Knowledge Management, addressing the

processes involved in order to benefit from the mi-

croblogging approach, and how they are enriched by

the use of semantics.

3.1 General Description

Unlike powerful yet complex Knowledge Manage-

ment solutions which expose a broad range of options

for the end-user, we propose a Web interface with a

single input option for end-users, where they are able

to express what are they doing, or more precisely in

a work environment, what are they working at. We

explain how this single input, which follows the sim-

plicity idea behind the microblogging paradigm, can

still be useful in a Knowledge Management solution

while reducing the general entry barriers of this kind

of solutions.

The purpose of the single input parameter where

end-users can write a message is twofold: Firstly, the

message is semantically indexed so it can be retrieved

later on (see section 3.2), as well as the particular

user associated to it; secondly, because the content

of the message itself is used to query the same in-

dex for relevant messages semantically related to it

(section 3.3), as well as end-users associated to those

messages (“experts”, section 3.4).

Supporting the process of indexing and retrieving

relevant information, domain ontologies are used so

messages can be associated even if they do not contain

the same expressions. The domain ontology is also

used in order to identify the areas in which the system

will identify experts.

In addition to the domain ontology, the system

takes advantage of the Linked Data paradigm(Bizer

et al., 2008) as an efficient manner of accessing struc-

tured data already available via Web, thus enriching

the system with external information (see section 3.5).

Finally, the system uses contextual information in

order to enrich the interactions of end-users with the

system. This way, the location information is also

stored in the semantic index, so it can be used in the

querying step to improve the suggestions (see section

3.6).

3.2 Message Indexing

When a user interacts with the system and a new sta-

tus message is created, this is indexed into a status

repository, permitting its efficient retrieval in the fu-

ture. Similarly, a repository of experts is populated

by relating the relevant terms of the message with the

particular author.

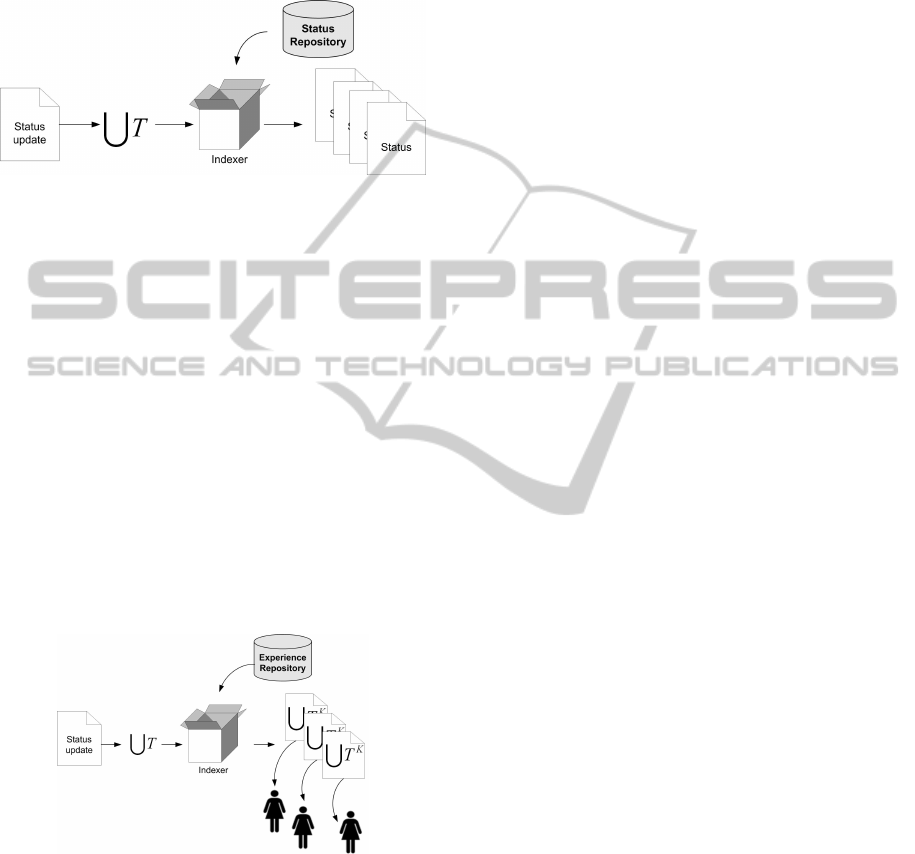

Figure 2: Message repository creation.

Technically, messages that users post to the sys-

tem are groups of terms T (both key-terms T

K

, rel-

evant terms from the ontology domain, and normal

terms)

S

T . The process of indexing each message re-

sults in a message repository that contains each doc-

ument indexed by the different terms it contains, as

shown in figure 2.

Figure 3: Employees expertise repository creation.

Additionally, the process of indexing a message

is followed by the update of a semantic repository of

experts. In this case, each user can be represented by a

group of key-terms (only those present in the domain

ontology)

S

T

K

. This way, the repository of experts

will contain the different users of the systems, that can

be retrieved by the key-terms. Figure 3 illustrates this

experts repository.

3.3 Message Search

As stated in 3.2, the posting of a new message by a

user subsequently triggers a search over the seman-

tic repository. This is performed seamlessly behind

the scenes, i.e., the user is not actively performing a

search, but the current status message is used as the

search parameter directly.

MIKROW

- An Intra-enterprise Semantic Microblogging Tool as a Micro-knowledge Management Solution

39

From a technical point of view, the semantic

repository is queried by using the group of terms

S

T

of the posted message, as depicted in figure 4. This

search returns messages semantically relevant to the

one that the user has just posted.

Figure 4: Detection of related statuses.

It is worth noting that the search process in the

repository is semantic, therefore the relevant mes-

sages might contain some of the exact terms present

in the current status message, but also terms semanti-

cally related through the domain ontology.

3.4 Expert Search

Along with the search for relevant messages, the sys-

tem is also able to extract experts associated with the

current status message being posted. As stated before,

the experts have been identified by the terms present

in the messages they have been writing previously.

In this case, the search over the semantic reposi-

tory of experts is performed by using the key-terms

contained in the posted message

S

T

K

, as depicted in

figure 5.

Figure 5: Expert identification.

3.5 Linked Data Boost

One of the issues of the previous approach is the need

of a global ontology that models as close as possible

the whole knowledge base of an enterprise, which, de-

pending on the size and the diversity of the company,

may differ from difficult to almost impossible (new

knowledge concepts being generated almost as fast as

they can be modeled).

As an open approach to solve this issue we

propose to take advantage of information already

available in a structured way via the Linked Data

paradigm, providing with an easy and mostly effort-

less mechanism for adding new knowledge to the

system knowledge base. Each new message posted

will be processed with NLP methods against the dis-

tributed knowledge base that the Linked Data Cloud

could be seen as. New concepts or instances ex-

tracted from that processing will be added to a tem-

porary knowledge base of terms that could be used

to add new information to the system’s ontology.

These terms would be semiautomatically added to the

knowledge via algorithms that weighs the instance us-

age and the final input of a ontology engineer that de-

cides whether the proposed terms are really valid or

is a residue from common used terms with no further

meaning to the company.

The main advantage of this approach is that it al-

lows the whole system to adapt to its real usage and

to evolve with an organic growth alongisde the evo-

lution of the company knowhow. That way, when a

new client starts to make business with the company

(or even before, when the first contacts are made)

some employees will probably start to post messages

about it (“Showing our new product to company C”,

“Calling company C to arrange a new meeting”,. . . ).

Querying the Linked Open Data Cloud will automat-

ically detect that this term C is indeed a company,

with a series of propierties associated to it (headquar-

ters location, general director and management team,

main areas of expertise,. . . ), and would allow for this

new knowledge to be easily added to the base knowl-

edge dataset.

3.6 Context-aware Knowledge

Management

Context was defined by Dey(Dey, 2001) as “any infor-

mation that can be used to characterize the situation of

an entity”, being an entity “a person, place, or object

that is considered relevant to the interaction between

a user and an application, including the user and ap-

plications themselves”. This definition, while inten-

tionally vague, clearly shows that user is surrounded

by information that can and must be used in order to

improve his/her interaction with applications.

While our current work does not try to leverage all

kind of context information or to even apply a formal

model at this point, it was quite obvious during our

research and particularly during the testing phase that,

although users have a clear perception of how a tool

like this can be improved by exploiting information

about themselves, answers are usually vague in terms

KMIS 2010 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

40

of which information do they really find relevant for

this kind of application.

For testing purposes we experimented with differ-

ent kinds of context awareness trying to narrow down

which ones where more useful in a work environment

like this, and particularly for knowledge management

purposes. Location was obviously the first variable

that provides useful information, with most users pre-

ferring a experts rank where user closeness was posi-

tively weighed. As well, a first step into leveraging

the dimension of social context was taken into ac-

count, by weighing up experts that where somehow

close socially (working in the same area or having

contacts in common) and thus more easily reachable.

4 CURRENT IMPLEMENTATION:

miKrow

The theoretical contribution covered in the previous

section has been implemented as a prototype, in or-

der to be able to evaluate and validate our ideas. The

nickname chosen for this prototype, miKrow, is based

on our micro-Knowledge Management approach. In

the following subsections, we address the implemen-

tation details and the evaluation performed.

4.1 miKrow Implementation

Figure 6 depicts the Web page of the current imple-

mentation of miKrow used within iSOCO, the com-

pany where the tool has been developed

4

. The inter-

face features a new stream of messages relevant to the

one just posted, and the Linked Data terms found in it.

Experts about relevant terms in the domain ontology,

in this case “context”, are highlighted as well.

4.1.1 Microblogging Engine

miKrow implements Jaiku

5

as the microblogging net-

work management layer, relying on it for most of the

heavy lifting related to low level transactions, persis-

tence management and, in general, for providing with

all the basic needs of a simple social network. Jaiku

was one of the first microblogging social networks

available, even earlier than the now omnipresent Twit-

ter, and, after being bought by Google, its source code

was released under an open source license.

Using Jaiku as an starting point reduced the bur-

den of a huge part of the implementation that should

4

Further information on this prototype at

http://mikrow.isoco.net/about

5

http://www.jaiku.com

have been devoted to all the middleware and infras-

tructure needed for even the simplest process such

as create a new user or post a new status update to

be functional, thus allowing the new development to

be completely focused in evolving the current mi-

croblogging state of art from a simple tool for post

and reading to an intelligent knowledge management

semantically-enabled environment.

The choice of Jaiku over other possibilities avail-

able is based essentially in its condition of having

been extensively tested and the feasibility of being de-

ployed in a cloud computing infrastructure(Armbrust

et al., 2009) such as Google App Engine

6

, thus reduc-

ing both the IT costs and the burden of managing a

system that could have an exponential growth.

4.1.2 Semantic Engine

The semantic functionalities are implemented in a

three layered architecture as shown in figure 3: on-

tology and ontology access is the first layer, keyword

to ontology entity mapping is the second one and the

last layer is semantic indexing and search.

For each company, an ontology modeling the

specific business field has to be implemented in

RDF/RDFS. Knowledge engineers and domain ex-

perts worked together to define concepts and relations

in the ontologies. Ontologies are accessed through the

Sesame RDF framework

7

.

An engine to map keywords to ontology entities

has been implemented in order to detect which terms

(if any) in the text of an idea are present in the ontol-

ogy. For this task we consider: morphological vari-

ations, orthographical errors and synonyms (for the

terms defined in the ontology). Synonyms are manu-

ally defined by knowledge engineer and domain ex-

perts as well. The indexes and the search engine

are based on Lucene

8

. Two indexes have been cre-

ated: user activities index and experts index. Each

index contains terms tokenized using blank space for

word delimitation and ontology terms as single to-

kens. When we look for related activities to a given

one the following tasks are executed:

• extraction of the text of the idea for using it as a

query string;

• morphological analysis;

• ontology terms identification (considering syn-

onyms);

• query expansion exploiting ontological relations.

6

http://code.google.com/appengine/

7

http://www.openrdf.org

8

http://lucene.apache.org/

MIKROW

- An Intra-enterprise Semantic Microblogging Tool as a Micro-knowledge Management Solution

41

Figure 6: miKrow implementation snapshot.

If a synonym of an ontology term is detected, the

ontology term is added to the query. If a term cor-

responding to an ontology class is found, subclasses

and instances labels are used to expand the query.

If an instance label is identified, the corresponding

class name and sibling instance labels are added to the

query. Different boosts are given to the terms used for

each different query expansion.

For expert detection, semantic search results are

filtered with statistical results about related activities.

In order to minimize the maintenance of the ontol-

ogy, we have added a system based on Linked Data

in order to identify relevant terms in the contents cre-

ated by the users. When a concept doesn’t belong to

the ontology, it can be identified as a relevant term if

Open Calais

9

returns an entry corresponding to that

concept.

4.2 miKrow Evaluation

An evaluation of the miKrow implementation was

carried in-house inside iSOCO where the application

was developed. iSOCO has currently around 100

employees distributed in 4 different cities all around

Spain, being this important geographical distribution

9

http://www.opencalais.com/

as well as their different knowledge backgrounds and

experience a common issue for sharing knowledge be-

tween different employees and branches of the com-

pany. The miKrow online application was made avail-

able for the workers to participate. Additionally, they

were asked to rank the suggestions the system made in

each occasion, and some of them also provided feed-

back. Qualitatively, some conclusions extracted from

Figure 7: Semantic architecture.

the evaluation process:

• The system was more useful and provided bet-

ter suggestions after an initial period of adapta-

tion where the messages were training the sys-

KMIS 2010 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

42

tem. Arguably, the integration of such a system

could be enhanced by the incorporation of previ-

ous existing knowledge into the system, e.g., pre-

defined experts that would be substituted gradu-

ally through the interactions with the system.

• Users were significantly more pleased with the

suggestions that involved semantics, when they

were presented with suggestions and experts with

different words than the ones they used, because

they perceived some sort of “intelligence” in the

system.

• Misleading suggestions were often caused by

stop-words that should not be considered, for in-

stance some initial activity gerunds (e.g., “work-

ing”, “preparing”). A system such as this one

should consider them to avoid providing wrong

suggestions.

From a quantitative point of view, during the eval-

uation period there was a considerable increase of in-

teractions of the workers with new tool, in compar-

ison with the previous existing systems such as the

intranet. One has to take into account, though, that

this increase is related to the context in which the new

system was introduced (as it was a project developed

in-house). A more consistent evaluation will be car-

ried out if the prototype evolves and is introduced in

an external-client.

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have presented the concept of a semantic mi-

croblogging tool to be used within an enterprise as a

lightweight method for Knowledge Management, ap-

plying Web 2.0 concepts in order to lower down the

entrance barriers for these kinds of systems, thus fos-

tering participation and increasing the utility of the

system. We have also described an implementation of

a tool that follows these ideas, miKrow, and the eval-

uation tests that have been possible thanks to it.

REFERENCES

Armbrust, M., Fox, A., Griffith, R., Joseph, A., Katz, R.,

Konwinski, A., Lee, G., Patterson, D., Rabkin, A.,

Stoica, I., et al. (2009). Above the clouds: A berkeley

view of cloud computing. EECS Department, Univer-

sity of California, Berkeley, Tech. Rep. UCB/EECS-

2009-28.

Bellinger, G. (1996). Systems thinking-an operational per-

spective of the universe. Systems University on the

Net, 25.

Bizer, C., Heath, T., Idehen, K., and Berners-Lee, T. (2008).

Linked data on the web (ldow2008). In WWW2008,

pages 1265–1266.

Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., and West, J. (2006).

Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm. Ox-

ford University Press, USA.

Davenport, T. (2005). Thinking for a Living. Harvard Busi-

ness School Press Boston.

Dey, A. K. (2001). Understanding and using context. Per-

sonal and Ubiquitous Computing, 5(1):4–7.

Fensel, D., Hendler, J., Lieberman, H., and Wahlster, W.

(2003). Spinning the semantic Web: Bringing the

World Wide Web to its full potential. MIT Press.

Graves, M. (2007). The relationship between web 2.0 and

the semantic web. In European Semantic Technology

Conference (ESTC2007).

Greenberg, S. and Marwood, D. (1994). Real time group-

ware as a distributed system: concurrency control and

its effect on the interface. In Proceedings of the 1994

ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative

work, pages 207–217. ACM.

Grudin, J. (1994). Computer-supported cooperative work:

History and focus. Computer, 27(5):19–26.

Hughes, J., Randall, D., and Shapiro, D. (1992). Faltering

from ethnography to design. In Proceedings of the

1992 ACM conference on Computer-supported coop-

erative work, pages 115–122.

Humphreys, L., Gill, P., and Krishnamurthy, B. (2010).

How much is too much? privacy issues on twitter. In

Conference of International Communication Associa-

tion.

McAfee, A. (2006). Enterprise 2.0: The dawn of emer-

gent collaboration. MIT Sloan Management Review,

47(3):21.

Nardi, B., Whittaker, S., and Bradner, E. (2000). Interaction

and outeraction: instant messaging in action. In Pro-

ceedings of the 2000 ACM conference on Computer

supported cooperative work, pages 79–88.

Neuwirth, C., Kaufer, D., Chandhok, R., and Morris, J.

(1990). Issues in the design of computer support for

co-authoring and commenting. In Proceedings of the

1990 ACM conference on Computer-supported coop-

erative work, page 195.

Patterson, J., Hill, R., Rohall, S., and Meeks, S. (1990).

Rendezvous: an architecture for synchronous multi-

user applications. In Proceedings of the 1990 ACM

conference on Computer-supported cooperative work,

page 328. ACM.

Surowiecki, J., Silverman, M., et al. (2007). The wisdom of

crowds. American Journal of Physics, 75:190.

Tang, J., Isaacs, E., and Rua, M. (1994). Supporting dis-

tributed groups with a montage of lightweight interac-

tions. In Proceedings of the 1994 ACM conference on

Computer supported cooperative work, page 34.

MIKROW

- An Intra-enterprise Semantic Microblogging Tool as a Micro-knowledge Management Solution

43