INFORMATION SECURITY IN HEALTH CARE

Evaluation with Health Professionals

Robin Krens, Marco Spruit

Departement of Information and Computing Science, Utrecht University, Padualaan 8, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Nathalie Urbanus-van Laar

UMC Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 100, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Keywords:

Information security, Evaluation and use of healthcare IT, Confidentialty, Integrity and availability.

Abstract:

Information security in health care is a topic of much debate. Various technical and means-end oriented

approaches have been presented over the years, yet have not shown to be sufficient. This paper outlines an

alternative view and approaches medical information security from a health professional’s perspective. The

Information Security Employee’s Evaluation (ISEE) is presented to evaluate and discuss medical information

security with health professionals. The ISEE instrument consists of seven dimensions: priority, responsibility,

incident handling, functionality, communication, supervision and training and education. The ISEE instrument

can be used to better understand health professional’s perception, needs and problems when dealing with

information security in practice. Following the design science approach, the ISEE instrument was validated

within a focus group of security experts and pilot tested as workshops across five hospital departments in two

medical centers. Although the ISEE instrument has by no means the comprehensiveness of existing security

standards, we do argue that the instrument can provide valuable insights for both practitioners and research

communities.

1 INTRODUCTION

Information security is involved with guaranteeing the

availability, integrity and confidentiality of informa-

tion (Stamp, 2006). In health care, correct and in-time

medical information is needed to provide high quality

care. Unavailable or unreliable information can have

serious consequences for patients, such as incorrect

or delayed treatment. Also, since this type of infor-

mation is uttermost sensitive, protecting the patient’s

privacy is another major security objective. From a

health professional’s point of view, information secu-

rity aspects concern issues such as in-time access to

medical information during consultation, fast recov-

ery during system downtime and assurance of data in-

tegrity.

Throughout the years different perspectives on in-

formation security have been described. Nonetheless,

it is often the technical perspective that has been the

main area of interest. Checklists, standards and risk

analysis are by far the most discussed methods within

this perspective. The general idea behind these meth-

ods is to identify all possible threats to information

and information systems, and to propose solutions.

Examples are the UNIX security checklists or the

ISO/IEC 27002 standard for information security (In-

ternational Organization for Standardization, 2005).

In contrast to the technical perspective, social

or human perspectives (Ashenden, 2008) are user-

centric and concentrate on user-related needs and

problems with information security. Examples of

user-related issues are lack of knowledge on privacy;

lack of computer training and problems with retriev-

ing data when needed.

Recent research subscribes the need for a more

social approach to information security (Dhillon and

Backhouse, 2001) (Siponen, 2005). Part of this ap-

proach is to enlighten on the human and cultural

elements of information security (Williams, 2008)

(Gaunt, 2000) . Another part is, since the increase

in vulnerabilities and complexity to health informa-

tion systems nowadays, to create methods to involve

health professionals actively within the domain of in-

formation security. (Ferreira et al., 2010), for exam-

61

Krens R., Spruit M. and Urbanus-van Laar N..

INFORMATION SECURITY IN HEALTH CARE - Evaluation with Health Professionals.

DOI: 10.5220/0003157700610069

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2011), pages 61-69

ISBN: 978-989-8425-34-8

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

ple, actively involve health professionals to the design

and enhancement of access control policies to elec-

tronic medical record systems.

Referring to the aspects of information security,

there also seems to be a tendency towards the confi-

dentiality aspect, overshadowing the other two: avail-

ability and integrity. Barber, for instance, states that

“the issues of integrity and availability will probably

deserve more attention than the issues of confiden-

tiality as medical information systems became more

inter-twined with clinical practice” (Barber, 1998).

This paper focuses on all aspects of medical in-

formation security seen from a health professional’s

point of view. The aim of the research is to build an

instrument to evaluate and discuss security of patient

information with health professionals. The developed

instrument, named ISEE (Information Security Em-

ployee’s Evaluation), can be used to better understand

user’s perception, needs and problems.

The paper is structured as follows. After this intro-

duction, the second section reviews related work. The

third section briefly describes the research approach.

The fourth section describes the development of the

ISEE instrument. Subsequently, the fifty section de-

scribes the validity and appliance of ISEE. The sixth

and final section discusses contributions, limitations

and future research for this study.

2 RELATED WORK

It is widely recognized that information security is

much more than technology. (Williams, 2008) states

that information security is not a technical problem

but mostly a human one. Williams identifies poor

implementation of security controls, lack of rele-

vant knowledge and inconsistencies between princi-

ples and practice as key issues. Williams also states

that a trusting hospital environment undermines the

need for proper supervision. In a culture of trust,

confidence in medical practice staff is high, result-

ing in little scrutiny of Internet usage, no policy on

changing passwords and unmonitored access to clin-

ical records. Fernando and Dawson (Fernando and

Dawson, 2009) show similar findings: poor quality

training and the hospital environment are constraints

on effective information security. Additionally, they

argue that wrongly implemented security controls can

result in workarounds such as the sharing of pass-

words or the usage of written clinical notes in case

of systems downtime. Security controls often take

time from patient care (i.e. logging out of a system).

Health professionals are skeptic about such controls

that form a constraint on their daily work and that

could, in the worse case, harm the patient. In a com-

plex environment were sensitive information is rou-

tinely recorded, spread and used it is a challenge to

guarantee the availability, confidentiality and integrity

of information.

As indicated in the introduction, most evaluation

methods of information security are technical and

risk based. Our aim is to evaluate information se-

curity with health professionals and for this purpose

we desire a different type of evaluation. In the dis-

cipline of information security such a comprehen-

sive type of evaluation does not exist yet. Most ex-

isting instruments are prescriptive (i.e. how should

end-user perform?) and focus strongly on the confi-

dentiality aspect. We, therefore, adapt an instrument

from the health care domain. The instrument, named

the Manchester Patient Safety Framework (University

of Manchester and National Patient Safety Agency,

2006), is used to discuss the physical safety of pa-

tients with health professionals. The following sub-

section gives a short overview of this Patient Safety

evaluation instrument.

2.1 The MaPSaF Instrument

The Manchester Patient Safety Framework (MaPSaF)

is an instrument to help health care teams assess the

safety of patients. Assessment with the instrument is

carried out in workshops, led by a facilitator from the

health care organization. The workshops starts by let-

ting each health professional individually rate dimen-

sions of the patient safety instrument. Dimensions of

this instrument are, for example, staff education and

investigation of patient safety incidents. Each dimen-

sion can be given a score, ranging from low (patho-

logic) to very high (generative). If, for example, a

nurse thinks that staff education is lacking to ‘safely’

perform her daily job, she can fill out a low score.

The next part of the workshop is concerned with the

comparison of score of the dimensions between par-

ticipants. Subsequently, a large part is dedicated to a

plenary discussion about the low scoring dimensions

and about what can be improved within the team or

organization. If possible, participants are encouraged

to create an action plan to improve the team’s safety

practices. The primary purpose of the instrument is

not merely to measure safety but to discuss safety

with employees. We have adapted MaPSaF for the

purpose of evaluating information security. The next

section describes what methods we followed to trans-

late MaPSaF to information security.

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

62

3 RESEARCH APPROACH

To adapt MaPSaF for evaluating medical informa-

tion security, we used the design science approach

(Hevner et al., 2004). The design science approach

consists of two main steps, namely (1) the develop-

ment and (2) the validation of an artifact. In our case,

the artifact is the ISEE instrument. For the adaption of

the MaPSaF instrument and development of the ISEE

instrument we performed a literature study. A large

part of the literature study was dedicated to construct

the evaluation ‘dimensions’ of the instrument. Valida-

tion of the instrument was performed within a focus

group of security experts and within a pilot study at

five hospital departments. Section 4 and 5 explain

these steps, and how we performed these steps, in

more detail.

4 DEVELOPMENT OF THE ISEE

INSTRUMENT

As said, based on the MaPSaF instrument we con-

structed the ISEE instrument. We adapted similar el-

ements of MaPSaF for the purpose to evaluate infor-

mation security with health professionals. In short,

ISEE consists of the following elements:

1. A maturity framework to discuss the level of se-

curity.

2. A variety of dimensions to rate information secu-

rity according to this maturity framework.

3. Evaluation with employees in the form of a work-

shop.

4.1 Maturity Scale

In the MaPSaF instrument, health professionals can

rate safety dimensions according to a maturity frame-

work. We copied this framework almost entirely to

information security with some slight changes in the

terminology. The framework was originally devel-

oped by (Westrum, 1993), and was later extended

by Reason (Reason, 1993) and Parker and Hudson

(Parker and Hudson, 2001). The framework consists

of five maturity levels: pathologic, reactive, bureau-

cratic, proactive and generative. Pathologic is de-

fined as a situation where safety (or security) prac-

tices are the barest industry minimum. There is no

top level commitment to the pursuit of safety (or se-

curity) goals. Reactive is an attitude where changes

are implemented after incidents or problems occur.

Bureaucratic is a situation where a lot is formalized

on paper, but practically a lot is failing. In contrast,

proactive and generative are the opposite of these sit-

uations. Table 1 shows an overview of these levels.

Health professionals can rate continuously with this

scale: they can, for example, rate a dimension as be-

tween reactive and bureaucratic (or as 2,5).

Table 1: Information security maturity level descriptions.

Score 1: Pathologic “Why waste our time on infor-

mation security?”

Score 2: Reactive “We act when we have an inci-

dent”

Score 2: Bureaucratic “We have systems in place to

manage risks”

Score 4: Proactive “We are alert on security re-

lated risks”

Score 5: Generative “Information security is a part

of everything we do”

4.2 Evaluation Dimensions

Patient safety dimensions were not directly applica-

ble for information security. The security dimensions

were, therefore, initially based on a literature review.

At first we identified over 30 user-related (i.e. lack

of knowledge, poor security implementation, unus-

able security controls, workarounds) security issues.

Since it was not feasible to include each of these is-

sues individually in this type of evaluation, we de-

cided to increase the level of abstraction. We pro-

vide a list of seven dimensions: priority, responsibil-

ity, incident handling, functionality of security, com-

munication, supervision and training and education.

Table 2 provides a general overview of these dimen-

sions. The table also shows how we mapped various

security issues from our literature study to a dimen-

sion. Though security involvesmany more topics than

discussed within the evaluation (i.e. network control

or protection against viruses), our perspective is re-

stricted to those security issues that were relevant to

health professionals.

4.3 Workshop Set-up and Participants

Evaluation of patient safety with the MaPSaF instru-

ment occurs in a two-hour workshop. The partici-

pants are a crosscut of a hospital department. Among

these participants are managers, doctors, nurses, tech-

nicians and other supporting staff. In that way, differ-

ent perspectives of the subject are highlighted. The

workshops are conducted by a sequence of steps de-

fined in a standard protocol. The workshop set-up and

protocol of MaPSaF was left the same for ISEE. The

following list shows the sequence of steps:

1. Individual evaluation: participants fill out the

evaluation individually.

INFORMATION SECURITY IN HEALTH CARE - Evaluation with Health Professionals

63

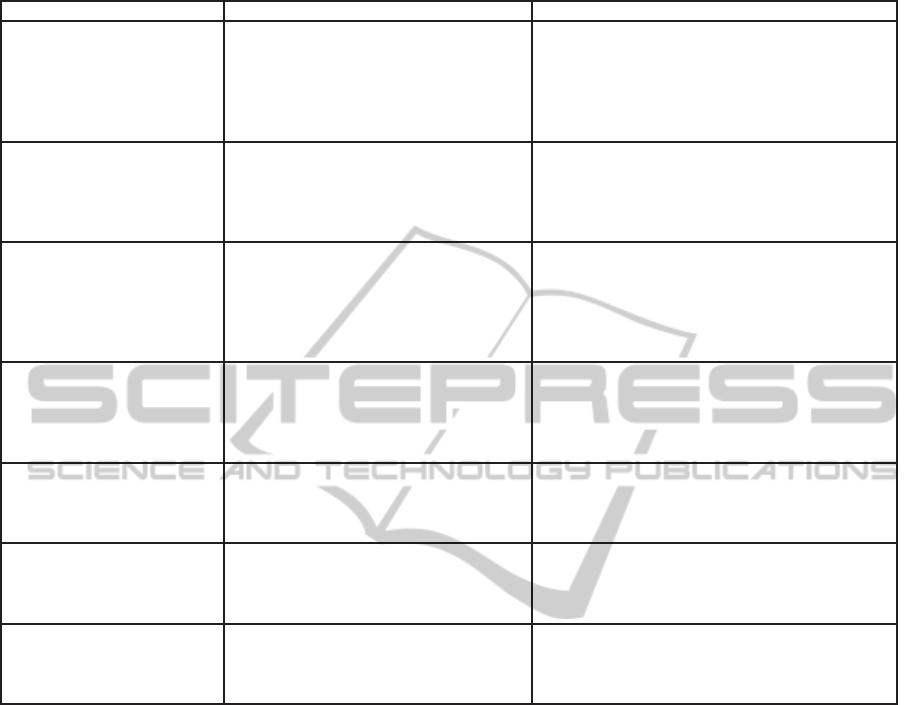

Table 2: Information Security Employee’s Evaluation (ISEE) dimensions.

Dimension Description Information security issues

Priority How important is security (availability,

integrity and confidentiality) of patient

information? What is done to provide

optimal security?

Lack of time (Fernando and Dawson, 2009)

(Nosworthy, 2000) (Williams, 2008), cost

(Williams, 2008), the hospital environment

(Fernando and Dawson, 2009), conflicting de-

mands (Gaunt, 2000) and productivity (Fer-

nando and Dawson, 2009)

Handling of incidents Is the importance of reporting inci-

dents (system failure, confidentiality

breaches, unsafe systems) recognized?

What is done with the report of an inci-

dent?

Lack of incident reporting and handling (Nos-

worthy, 2000) and response (OECD, 2002)

Responsibility Who or what is responsible for medical

information security?

Attitude and ignorance (Williams, 2008)

(Gaunt, 2000), lack of awareness and responsi-

bility (Nosworthy, 2000) (OECD, 2002), skep-

ticism (Fernando and Dawson, 2009), data frag-

mentation (Fernando and Dawson, 2009) and

underestimation of threats (Nosworthy, 2000)

Functionality Is security supported in daily working

routines? Do health care professional

think this works well?

Usability (Fernando and Dawson, 2009) (Fer-

reira et al., 2010), Workarounds (Fernando

and Dawson, 2009), poor implementation

(Williams, 2008), inadequate systems (Gaunt,

2000) and security design (OECD, 2002)

Communication How is the communication about med-

ical information security? Do health

care professionals know what is ex-

pected?

Communication (Nosworthy, 2000), commu-

nication and feedback (Kraemer and Carayon,

2005) and inconsistent policies and communi-

cation (Gaunt, 2000)

Supervision Is the correct usage of medical informa-

tion examined?

Audit and supervision (Fernando and Dawson,

2009), trust (Williams, 2008), ethics (OECD,

2002), reward, punishment and hiring practices

(Kraemer and Carayon, 2005)

Training and education What about the knowledge around med-

ical information security? Do health

care professionals know how to act?

Training shortcomings (Fernando and Dawson,

2009) (Kraemer and Carayon, 2005), lack of

knowledge (Williams, 2008), capability and ed-

ucation (Williams, 2008), (Nosworthy, 2000)

2. Work in pairs: participants discuss their percep-

tions with another participant. They are encour-

aged to explain their scores and exchange anec-

dotes and personal experiences.

3. Group discussion: general discussion about

strength, weaknesses and differences in percep-

tions.

4. Action planning: the creation of an action plan for

weak security issues.

5 VALIDATING THE ISEE

INSTRUMENT

Validation of the ISEE instrument was examined from

two perspectives, namely (1) through a focus group

with security experts, and (2) through a pilot study

to actually apply ISEE in the field at hospital depart-

ments.

5.1 Focus Group

We conducted a focus group with security experts to

further enhance ISEE. A focus group is a form of a

group interview that capitalizes communication be-

tween participants to generate data (Pope et al., 2006).

A focus group was chosen to stimulate discus-

sion between experts. Focus groups encourage peo-

ple to talk to one another, ask questions, exchange

anecdotes and comment on each others’ experiences

and points of views. By these means, focus groups

are considered to have high face validity (Pope et al.,

2006). The purpose of focus group was:

• to determine whether the proposed instrument

could be useful to organizations (usefulness).

• to validate the instrument: Do participants under-

stand the concepts? Have we overseen important

user related security issues? Do they think the in-

strument is valid (face validity)?

• to evaluate the willingness to use the instrument

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

64

and the set-up requirements (time and people) of

the instrument (feasibility).

Table 3: Focus group participants.

Function Hospital

Security Officer LUMC (Leiden)

Security Officer Erasmus MC (Rotterdam)

Staff employee IT UMC Utrecht

Security Officer AMC (Amsterdam)

Security Officer UMC Nijmegen

IT Auditor UMC Nijmegen

Security Officer UMC Groningen

IT manager LUMC (Leiden)

IT Security Officer UMC Utrecht

The type of focus group we used was a dual mod-

erating focus group. One moderator ensured that the

session ran smoothly (i.e. involving each participant

and cutting irrelevant issues). The other moderator

observed behavior, took notes, and ensured all rele-

vant topics were covered. The participating experts

were able to respond freely during the session.

Participants were able to understand the concepts

and recognized the differences between levels. For

instance, in case supervision is reactive or proactive

at a hospital department. It was argued, however,

that a higher maturity is not a goal in itself. Dis-

cussion should be the primary goal of ISEE. Partic-

ipants argued that there was no need to reach consen-

sus within a workshop. Discussion should be based

on the differences between scores. The participants

argued that two dimensions should be further defined.

The dimension Functionality should not only incor-

porate functionality of access security controls, but

also incorporate functionality of information systems

regarding availability. Supervision should also in-

clude issues about staff management such as hiring

employees.

The experts acknowledged that evaluation should

occur in a small group, preferably a department or

team. Participating health care workers should be a

crosscut of a hospital department. For feasibility rea-

sons it was suggested to condense the workshop time

into one and a half hour. To simplify the evaluation,

each dimension should be provided with a few exam-

ples per maturity level.

The results of the focus group were incorporated

in the instrument and verified by the experts through

mail inquiry. Table 4 shows the ISEE instrument with

abbreviated examples.

5.2 Pilot Study

The ISEE instrument was pilot tested during five

workshops of one and a half our each. The work-

shops were held at five hospital departments in two

university medical centers in the Netherlands. The

participants of each of these workshop are listed in

Table 6. The goal of the workshops was to test if the

instrument is applicable in a practical setting. At each

workshop the face validity and feasibility of the in-

strument were investigated. We asked the participants

if they found the evaluation useful and if they thought

the scope of information security was covered. Fea-

sibility concerned boundary conditions such as the

amount of time. Since the instrument is not a pure

measurement instrument validation was kept qualita-

tive. The original instrument, MaPSaF, was also vali-

dated in this nature. Additionally, we performed some

descriptive statistics on the scores given by the partic-

ipants. Table 5 shows an example of calculated met-

rics including floor and ceiling values. These statis-

tics were used to reconstruct what was said during the

workshops. Each workshop was evaluated individu-

ally. Comments made during workshops were used

to enhance the ISEE instrument. Due to paper length

constraints, we only discuss one of the workshops in

more detail.

5.2.1 One Workshop Highlighted

One of the workshops was held at a Radiotherapy de-

partment. There was a total of seven participants. See

Table 6 for an overview of participants and Table 5

for the descriptive statistics over the scores. The low-

est scoring dimensions were Supervision and Training

and education. The highest scoring dimensions were

Responsibility and Handling of incidents. Most stan-

dard deviations of the dimensions indicate an accept-

able distribution of responses. Handling of incidents

and supervision show the highest variance. Manage-

ment of the radiotherapy department was very posi-

tive on handling of security incidents, which explains

the variance. The range of scores on supervision is

also broad. Management was also more positive to-

wards this dimension then direct health care workers.

The difference in perception brought to light that ac-

cess control mechanism were not fully implemented.

Most participants prioritize the availability and

sharing of information. This may have consequences

on the confidentiality aspects. Most participants

agreed that more awareness on confidentiality of pa-

tient information is desirable. Some even came up

with a proposal, such as introducing privacy concerns

to new employees or to make ‘confidentiality and

electronic medical records’ a recurrent theme. The

INFORMATION SECURITY IN HEALTH CARE - Evaluation with Health Professionals

65

Table 4: The ISEE instrument with abbreviated examples.

Dimension 1: Pathologic 2: Reactive 3: Bureaucratic 4: Proactive 5: Generative

Priority: how important

is security (availability, in-

tegrity and confidentiality

of patient information?

Risks are not

recognized

After incidents

there is an in-

crease in prior-

ity

Now and

then plans

are made for

improvements

Plans are made

and evaluated

Employees are

involved, secu-

rity is a man-

agement cycle

Incident handling: is the

importance of report-

ing incidents (system

failure, confidentiality

breaches, unsafe systems)

recognized?

It is not clear

how and where

incidents

should be

reported

Incidents are

handled un-

structured and

on ad-hoc basis

There is a for-

mal reporting

systems, but

is not fully

implemented

Incidents

are handled

swiftly.

Trend analysis

takes place to

prevent inci-

dents for future

happenings

Responsibility: who or

what is responsible for

medical information secu-

rity?

Information se-

curity is not my

responsibility

Security is

something

management

does

Security is

about defin-

ing roles and

responsibilities

Security is ev-

erybody’s con-

cern.

Employees

know how

to enhance

security

Functionality: do systems

support security in daily

working routines?

Functionality

comes with the

systems

Temporary so-

lutions are con-

structed

Needed sys-

tem security

functionality is

planned

Systems work

correctly and

new improve-

ments are

considered

Systems fully

support the

process of care!

Communication: how is

the communication about

medical information secu-

rity?

There is no pos-

sibility to dis-

cuss concerns

Communication

is one way

Communication

is paper work

Communication

is a two-way

process

Employees are

aware and have

a questioning

attitude

Supervision: is the correct

usage of medical informa-

tion examined?

Incorrect usage

has no conse-

quences

Sanction are

taken by severe

shortcomings

Most of pro-

cedures are in

place

Evaluation

of behavior

is done on

periodic basis

Management

and employees

are widely

involved on this

topic

Training and education: do

health care professionals

know how to act?

Employees

should not be

bothered with

security

Training is

done if it is

an absolute

necessity

Training is

highlighted, but

not enforced

Employees are

encouraged to

participate

Training is part

of the day-to-

day job

Table 5: Workshop II: Radiotherapy (scores are based on 7 participants).

INSTR. Dimensions Mean (1-5) Std Range (1-5) Floor (x) Ceiling (x)

Priority 3,21 0,69 2-4 0 0

Handling of incidents 3,42 0,93 2-5 0 1

Responsibility 3,29 0,57 2,5-4 0 0

Functionality 2,71 0,57 2-3,5 0 0

Communication 2,93 0,84 2-4 0 0

Supervision 2,57 0,98 1-4 1 0

Training and education 1,93 0,45 1-2,5 1 0

discussion also brought forward that many security

issues (such as automatic logging out of systems) can

be easily implemented. However, a reactive attitude

causes that this does not happen. As one participants

stated: “things should go wrong, before something

eventually happens”.

Furthermore, a variety of contemporary issues

were discussed. Amongst these were:

• Unavailability of patient’s status information.

• Slow security incident handling according to

some health care workers.

• Poor integration with another system which made

it impossible to write down medical information.

• The transition towards electronic medical records

systems made that information was scattered

(partly digital and partly on paper).

Based on these differences between experiences

regarding the supervision and functionality dimen-

sions the department created an action plan. Par-

ticipants considered the workshop useful to discuss

information security. Most participants encouraged

the multidisciplinary setup to discuss different per-

ceptions on information security. Some participants,

however, considered the instrument to be a bit man-

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

66

Table 6: An overview of all participants in the pilot study and their associated scores.

Department and participants P I R F C S T

Workshop I: Radiology

Quality Assurance Officer 2,5 3 2 3,5 2 2 2,5

Doctor 3 2 3 3,5 2 3 1,5

Doctor 2,5 3 3 3 2 1 2

Head Front Office 3 2,5 3 2 2 2 2

Front Office Secretary 2 3,5 3 2,5 1,5 2,5 2

Team Leader Front Office 2 2,5 4 3,5 1,5 2,5 2

IT system controller 2,5 2,5 4 2,5 2 2 2

Unit head Angiography 3 3,5 3,5 3 2 3 2,5

Workshop II: Radiotherapy

Manager Quality Assurance 3 4 3 3 4 4 1

Manager Department 3 5 3,5 2,5 2 3 2

Doctor 4 3,5 3 2 3 1 2

Head of Laboratory 3,5 3,5 3 3 2 3 2,5

Laboratory worker 2 3 4 2 4 2 2

Laboratory worker 3 2 2,5 3,5 2,5 3 2

Front Office / secretary 4 3 4 3 3 2 2

Workshop III: Skin Diseases

Chef de Clinique 3 3,5 4 2 4 3 4

Medical Head doctors 3 1 3 1 2 1 2

Head of secretary 4 3 3 3,5 2 3 2

Medical secretary 3 3 3 3,5 2 1 2

Doctor 3 2,5 3,5 3 2 2 3

Doctor 3 4,5 3 4 3,5 2 3

Doctor 3 3,5 4 2 3 3 4

Doctor 2,5 3 4 1 3 2,5 4

Photographer 3 4 4 4 3 1 2

Nurse 3 3 4 1 3 2 4

Worksoph IV: Hematology and Short Stay

Head Nursing 2,5 2,5 3,5 3 2,5 2,5 3

Team Leader Nurses 3 3,5 3,5 3,5 2 2 1,5

Senior Nurse 2,5 2 3,5 2,5 3,5 5 3,5

Senior Nurse 4 3,5 4 3,5 4 3 4,5

Medical secretary 3,5 4 4 3 2,5 3,5 2

Medical secretary 3,5 3 3,5 2 3 3 2

Team Leader / Senior nurse 3,5 3,5 3,5 3 3 2 3,5

Stem cell coordinator / nurse 3 4 3 3 3,5 3 3,5

Workshop V: Urology

Head nursing 2,5 2,5 3 2 3,5 1,5 2

Team leader urology 2,5 2,5 4 3 2 3 2

IT coordinator 3 4 3,5 3,5 3,5 2,5 3

Doctor’s assistant 4 3,5 4 3 4 2,5 2,5

Nurse 2,5 3,5 4 3 3 2 2

Secretary 3,5 3 4 3 3,5 2 2

Doctor’s assistant/secretary 2,5 5 4 2 2 4 2

P=priority, I=incident handling R=responsibility, F=functionality,

C=communication, S=supervision, T=training and education

1=pathologic, 2=reactive, 3=bureaucratic, 4=proactive, 5=generative

agerial. Some participants suggested to remove all

managerial examples.

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

Health professionals are the first in line to experience

disturbances with the availability and integrity of pa-

tient information. Furthermore, concerning the confi-

dentiality of information, they play an important role

INFORMATION SECURITY IN HEALTH CARE - Evaluation with Health Professionals

67

in the protection of such information. Based on the

MaPSaF instrument, that discusses the safety of pa-

tients, we constructed the Information Security Em-

ployee’s Evaluation (ISEE) to evaluate information

security with health care workers.

Overall, this pilot study showed that the instru-

ment is useful to:

• Discuss medical information security within a

hospital department.

• Identify and discuss weak and strong points.

• Discuss different perceptions on information se-

curity between employees.

A workshop can best be held at one single depart-

ment (i.e. an outpatient clinic or nursing department).

At Workshop IV two departments participated. Some

security issues that were problematic at one depart-

ment (availability of electronic nursing records) were

neverheard of at the other department. It was interest-

ing to see such differences between departments. It is,

however, hard to discuss and identify single points for

improvements with such diverse groups. We, there-

fore, recommend using the evaluation within a single

department.

The multidisciplinary set-up of participants high-

lighted various perceptions on information security.

For instance, Workshop III indicated that manage-

ment had a very positive view on incident handling.

Further discussion however, showed that staff had no

idea how to report problems, and even when they did,

they were not pleased with the department’s solving

skills. At Workshop II the multidisciplinary set-up

even took care of some quick fixes: A doctor indi-

cated that during night shift, magnetic resonance in-

formation about patients was not available. An em-

ployee of the IT supportive staff argued that this was

an unknown issue, yet provided a quick solution.

Reflecting on all five workshops of the pilot study,

we found that the dimensions priority and responsi-

bility show the least amount of variance and range

of scores. These dimensions, since they relate to

attitude, might suffer social desirability bias. Floor

effects occurred most frequently at the dimensions

functionality and supervision. A majority of these

low scores was explained by the participants. Ceiling

scores were only given by management staff. Overall,

management gave relatively higher scores than direct

health care workers which might indicate a too opti-

mistic view by management.

For future purposes, it might be interesting to fur-

ther develop the instrument and apply it as a measure-

ment instrument in a survey-format. Dimensions can

be further defined with specific characteristics. To

give an example, the dimension training and educa-

tion could be further defined on the issues ‘knowledge

of privacy legislation’, ‘knowledge of information se-

curity’ and ‘knowledge on how to use security con-

trols’. Such refinement makes the instrument more

applicable for actual measurement within a hospital

environment. Further work, then, will be needed to

address these characteristics specifically. Also, such

a measurement instrument, gives opportunities to ex-

amine in greater depth the instrument’s psychometric

properties including measures of internal consistency,

reliability and construct validity.

This research has shown that the ISEE instrument

can effectively assist health professionals in their ef-

forts to improveinformation security within their hos-

pital departments. The ISEE instrument has by no

means the comprehensiveness and completeness of

existing standards or other security checklists. We do,

however, argue that the instrument and the human per-

spective can provide additional insights. Implement-

ing secure systems does involve health care workers,

both in respect of functionalsecurity controls as in hu-

man characteristics such as awareness, responsibility

and knowledge.

REFERENCES

Ashenden, D. (2008). Information security management:

A human challenge? Information Security Technical

Report, 13(4):195–201.

Barber, B. (1998). Patient data and security: an

overview. International Journal of Medical Informat-

ics, 49(1):19–30.

Dhillon, G. and Backhouse, J. (2001). Current di-

rections in IS security research: towards socio-

organizational perspectives. Information Systems

Journal, 11(2):127–154.

Fernando, J. I. and Dawson, L. L. (2009). The health infor-

mation system security threat lifecycle: An informat-

ics theory. International Journal of Medical Informat-

ics, 78(12):815–826.

Ferreira, A., Antunes, L., Chadwick, D., and Correia, R.

(2010). Grounding information security in health-

care. International Journal of Medical Informatics,

79(4):268–283.

Gaunt, N. (2000). Practical approaches to creating a secu-

rity culture. International Journal of Medical Infor-

matics, 60(2):151–157.

Hevner, A. R., March, S. T., Park, J., and Ram, S. (2004).

Design science in information systems research. MIS

Quarterly, 28(1):75–105.

International Organization for Standardization (2005). In-

formation technology – security techniques – code of

practice for information security management. Tech-

nical Report ISO/IEC 27002:2005, International Or-

ganization for Standardization, Geneva.

HEALTHINF 2011 - International Conference on Health Informatics

68

Kraemer, S. and Carayon, P. (2005). Computer and infor-

mation security culture: Findings from two studies.

In Human factors and the Ergonomics Environment,

pages 1483–1487, Orlando. Human Factors and the

Ergonomics Society.

Nosworthy, J. D. (2000). Implementing information secu-

rity in the 21st century do you have the balancing fac-

tors? Computers & Security, 19(4):337–347.

OECD (2002). Guidelines for the security of information

systems and networks: Towards a culture of secu-

rity. Technical report, Organization for Economic Co-

operation and Development, Paris.

Parker, D. and Hudson, P. T. (2001). HSE: Understanding

your culture. Shell International Exploration and Pro-

duction, EP 2001 - 5124.

Pope, C., Mays, N., and Kitzinger, J., editors (2006). Qual-

itative research in health care, chapter Focus Groups,

pages 21–31. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 3rd edi-

tion.

Reason, J. (1993). The identification of latent organiza-

tional failures in complex systems. In J.A. Wise,

V.D. Hopkin, P. S., editor, Verification and identifica-

tion of complex systems: human factor issues, pages

223–237, New York. Springer-Verlag.

Siponen, M. T. (2005). An analysis of the traditional IS

security approaches: implications for research and

practice. European Journal of Information Systems,

14(3):305–315.

Stamp, M. (2006). Information security: principles and

practice. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, 2nd edition.

University of Manchester and National Patient Safety

Agency (2006). Manchester patient safety framework

MaPSaF. http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk.

Westrum, R. (1993). Cultures with requisite imagination. In

J.A. Wise, V. D. Hopkin, P. S., editor, Verification and

Validation in Complex Man-machine Systems, pages

401–416, New York. Springer-Verlag.

Williams, P. A. H. (2008). When trust defies common se-

curity sense. Health Informatics Journal, 14(3):211–

221.

INFORMATION SECURITY IN HEALTH CARE - Evaluation with Health Professionals

69