POST-ADOPTION BEHAVIOUR, COMMUNITY SATISFACTION

AND PCS

An Analysis of Interaction Effects in the Tuenti Community

Manuel J. Sánchez-Franco, Félix A. Martín-Velicia and Borja Sanz-Altamira

Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Sevilla University, Avda. Ramon y Cajal, n1, 41018, Sevilla, Spain

Keywords: Routinisation, Community satisfaction, Perceived community support.

Abstract: Our research contributes to the existing literature by examining the community drivers (i.e., participation,

organisation and satisfaction) and their effects on the sense of belongingness to a social networking site. Our

analysis also emphasises the importance of continuance over initial acceptance; indeed, post-adoption

phenomena have traditionally received scarce attention. In particular, our study will consider the interaction

effects of routinisation on the research model. A survey is conducted for data collection. Partial Least

Square (PLS) is proposed to assess the relationships between the constructs together with the predictive

power of the research model. Overall, the results reveal that members’ attachment to an online community

is determined by community satisfaction, participation and organisation. Moreover, higher routinisation

reduces the impact of community organisation on integration, and in turn increases the impact of

satisfaction on integration. The model and results can consequently be used to assess different strategic

proposals related to participation, organisation and satisfaction during the implementation process.

1 INTRODUCTION

Social networking sites (SNSs) are conceptualised as

online environments that foster mutual support and

participation in community activities, individual’s

feelings of attachment to them and expectations of

continuity (cf. Herrero and Gracia, 2007, see also

Blanchard, 2007, Blanchard and Markus, 2004,

2007, McMillan and Chavis, 1986, Sánchez-Franco

and Roldán, 2010). Perceived community support

(hereinafter, PCS) will be conceived as an

appropriate means of explaining the success of the

accumulative/enduring relationships between the

SNS and its members, based on community

satisfaction. Community satisfaction reinforces the

members’ decision to participate in the delivery of

the service. However, assuming that the success of a

community derives from the development and

sustainability of its members, post-adoption analysis

has, compared to the established research stream of

SNS adoption and initial usage, received less

attention. Particularly, routinisation behaviours

moderate the purpose of social communicating at a

specific SNS, and provide scholars with a growing

understanding of their interaction effects on the

relationships between the community drivers and the

sense of attachment to their SNS.

The purpose of this research will, therefore,

expand previous research of what contributes to

integration. This study will describe routinisation as

a moderating driver for modifying feelings of

attachment with an SNS in a larger effort to reduce

loneliness (as opposed to social integration).

2 THEORY AND RESEARCH

HYPOTHESES

This research presents a PCS structure that includes

three dimensions (cf. Herrero and Gracia, 2007).

Community organisation will, on the one hand, be

defined as feelings of being supported by the online

community -while also supporting other users (cf.

Blanchard and Markus, 2004). On the other hand,

community participation will be conceptualised as

community involvement, active participation in SNS

activities, or social participation in order to help

other virtual community members–which includes

expressions of encouragement related to members’

concerns. The exchange of mutual support will be an

essential motive for the developing of virtual

communities (Baym, 1997, Rothaermel and

Sugiyama, 2001, Wellman and Guilia, 1999).

459

Sánchez-Franco M., A. Martín-Velicia F. and Sanz-Altamira B..

POST-ADOPTION BEHAVIOUR, COMMUNITY SATISFACTION AND PCS - An Analysis of Interaction Effects in the Tuenti Community.

DOI: 10.5220/0003297404590465

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2011), pages 459-465

ISBN: 978-989-8425-51-5

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Furthermore, community integration will be defined

as “members’ feelings of membership, identity,

belonging, and attachment to a group that interacts

primarily through electronic communication”

(Blanchard, 2007, p.827, cf. also Blanchard, 2008,

McMillan and Chavis, 1986).

In this social context, “community participation

provides members with numerous opportunities for

supportive communication” (Welbourne, 2009,

p.32). Firstly, greater levels of community

participation in an SNS (such as posting and

responding to messages) help to share knowledge

and ideas related to mutual interest, and,

subsequently, foster their attachment to it (cf. Koh

and Kim, 2004, Sánchez-Franco and Roldán, 2010).

Secondly, a member will be more highly motivated

to contribute to community if one receives useful

(and/or emotional) help in return (i.e., community

organisation) –or future reciprocity. Greater levels of

community organisation will lead members to feel

that they are being supported by a whole portion of

their community, reducing the uncertainty of the

relationship with it and fostering their social

participation and commitment. Thirdly, community

organisation will increase feelings of attachment to

their SNS, and expectations of continuity -so that

members will continue obtaining affective benefits

from mutual relationships (cf. Casaló et al., 2007).

Community participation and organisation will,

therefore, be associated with an increase in the

opportunity for the members to become involved in

a community and a reduction in their feeling of

community loneliness. Based on the previous

arguments, this research proposes the following

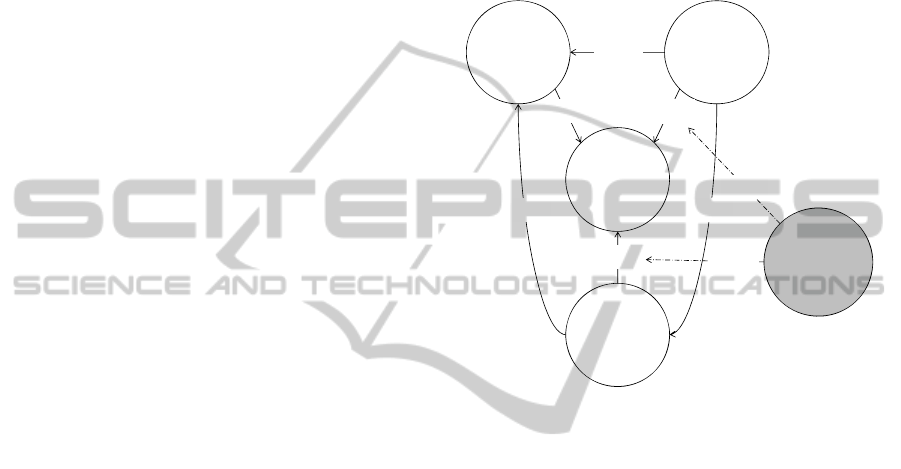

hypotheses: H1. Community participation positively

influences community integration, H2. Community

organisation positively influences community

participation, and H3. Community organisation

positively influences community integration. See

Figure 1.

Moreover, community satisfaction will be the

positive result of an overall assessment of

psychosocial aspects of a relationship between the

member and the other community members.

Stronger feelings of being supported by the online

community will, on the one hand, be associated with

higher community satisfaction. On the other hand,

“if the community members were not satisfied, there

would not be any incentive to participate in the

community” (Casaló et al., 2010). Satisfaction will

finally lead to desirable outcomes such as

cooperation, long-term orientation, loyalty, and

relationship integration (Ganesan 1994, Lam et al.

2004). It may, therefore, be argued that community

satisfaction precedes community integration (e.g.,

Sánchez-Franco and Rondán, 2010). Based on the

previous arguments, this research proposes the

following hypotheses: H4. Community organisation

positively influences community satisfaction, H5.

Community satisfaction positively influences

community participation; and H6. Community

satisfaction positively influences community

integration. See Figure 1.

Community

participation

Community

organisation

Community

integration

Community

satisfaction

Routinisation

H2[+]

H2[1]

H3[+]

H7[‐]

H6[+]

H8[+]

H5[+] H4[+]

Figure 1: Theoretical model.

Finally, as members use an SNS routinely, they

will simplify relationships with others by generating

a knowledge structure. In particular, routinisation is

associated with “habitual usage–that is, to integrate

the technology into daily routines” (Schwarz and

Chin, 2007, p. 240, cf. also Cooper and Zmud, 1990,

Saga and Zmud, 1994). Routinised members will

progressively underestimate members’ feelings of

being assisted by the online community “in terms of

support needs and resources available to the

individual” (Herrero and Gracia, 2007, p. 210).

Moreover, because the SNS is an important part of

the member's life, highly- routinised members have

strong motivations to avoid dissatisfaction.

Fulfilling, gratifying, and easy access to community

features (among highly-routinised behaviour) will

indeed reinforce the spontaneous tendency to go

back to a preferred SNS. Satisfaction -with daily

procedures for dealing with SNSs- could then

constitute one type of switching costs because it will

become essential if the members question the

relationship (cf. Sánchez-Franco, 2009). Based on

the previous arguments, this research proposes the

following hypotheses: H7. Overall, routinised

behaviour moderates (weakens) the relationship

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

460

between community organisation and community

integration; and H8. Overall, routinised behaviour

moderates (strengthens) the relationship between

community satisfaction and community integration.

See Figure 1.

3 METHOD

3.1 Participants

The structural model was validated empirically

using data from a field survey of the most popular

computer-mediated SNS among the Spanish college

student population, Tuenti. Particularly, participants

were recruited from social studies at a public

University in Seville (Spain). The exclusion of

invalid questionnaires due to duplicate submissions

or extensive empty data fields resulted in a final

convenience sample of 278 users. 42.8% were male

respondents. The average age was 21.04 (SD:

2.403).

3.2 Measures

Fourteen items were used to assess community

participation, organisation and integration (or

identification with an SNS) -taken from Herrero and

Gracia (2007), Geyskens et al. (1996), Loewenfeld

(2006), and Sánchez-Franco (2009). On the other

hand, a total of three items were employed to

measure community satisfaction (Gustafsson et al.,

2005). Finally, the instrument for measuring the

degree of routinised behaviour has been

operationalised by Sundaram et al. (2007) in the

form of a three-item scale.

A pretest assessed the suitability of the wording

and format, and the extent to which measures

represented all facets of constructs. All items are

seven-point Likert-type, ranging from «strongly

disagree», 1, to «strongly agree», 7.

3.3 Data Analysis

The hypotheses testing is conducted using Partial

Least Squares (PLS), specifically, SmartPLS 2.0.M3

software (Ringle et al., 2008).

Taking into account that hypotheses 7 and 8 are

based on interaction effects, one well-known

technique has had to be applied to test these

moderated relationships: product-indicator approach

(Henseler and Fassott, 2010).

4 RESULTS

4.1 Measurement Model

The measurement model was evaluated using the

full sample (278 individuals) -all items and

dimensions- and then the PLS results were used to

eliminate possible problematic items.

On the one hand, individual reflective-item

reliability was assessed by examining the loadings of

the items with their respective construct. Individual

reflective-item reliabilities –in terms of standardised

loadings– were over the recommended acceptable

cut-off level of 0.7. See Appendix.

On the other hand, construct reliability was

assessed using the composite reliability (ρ

c

). The

composite reliabilities for the multiple reflective

indicators were well over the recommended

acceptable 0.7 level, demonstrating high internal

consistency. Moreover, we checked the significance

of the loadings with a bootstrap procedure (500 sub-

samples) for obtaining t-statistic values. They all are

significant. See Appendix.

Finally, convergent and discriminant validities

were assessed by stipulating that the square root of

the average variance extracted (AVE) by a construct

from its indicators should be at least 0.7 (i.e., AVE >

0.5) and should be greater than that construct’s

correlation with other constructs. All latent

constructs satisfied these conditions. See Appendix.

i

4.2 Structural Model

The bootstrap re-sampling procedure (500 sub-

samples) is used to generate the standard errors and

the t-values. Firstly, the research model appears to

have an appropriate predictive power for

endogenous constructs to exceed the required

amount of 0.10 –R-square values. A measure of the

predictive relevance of dependent variables in the

proposed model is the Q

2

test. A Q

2

value (i.e., only

applicable in dependent and reflective constructs)

greater than 0 implies that the model offers

predictive relevance. The results of our study

confirm that the main model offers very satisfactory

predictive relevance: community integration (Q

2

=

0.404 > 0), community participation (Q

2

= 0.272 > 0)

and community satisfaction (Q

2

= 0.172 > 0).

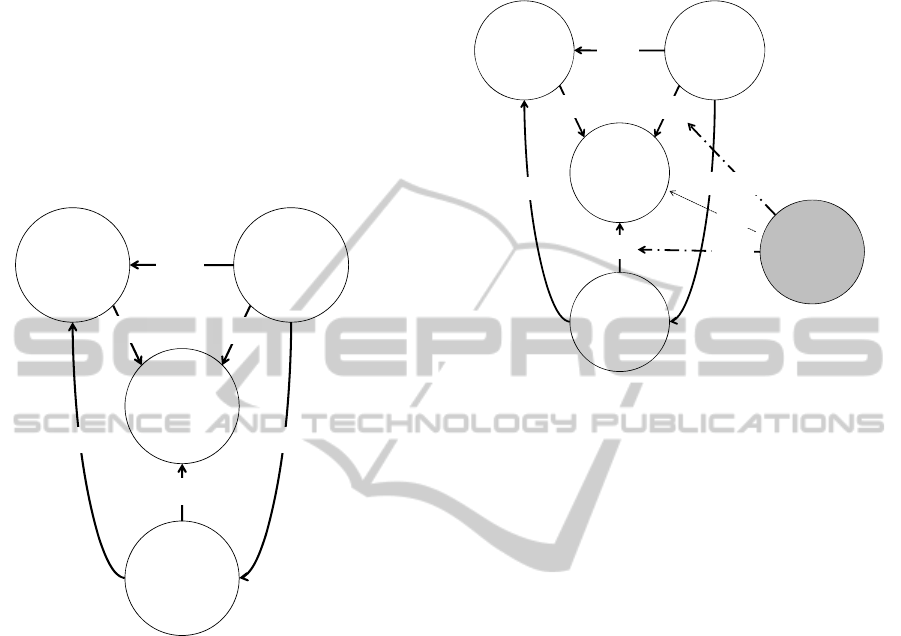

The data fully supported the models (i.e., the

main effects model and the interaction effects

model) and all hypotheses are supported on the basis

of empirical data. As indicated in the main effects

model, community participation and organisation

have a significant impact on integration, with path

POST-ADOPTION BEHAVIOUR, COMMUNITY SATISFACTION AND PCS - An Analysis of Interaction Effects in the

Tuenti Community

461

coefficients of 0.405 (t=8.231, p<0.001) and 0.204

(t=3,612, p<0.001) respectively. Community

organisation also has a significant effect on

community participation (β=0.401; t=6.884,

p<0.001).

Furthermore, community satisfaction shows a

relevant impact on community integration (β=0.327;

t=5.906, p<0.001) and community participate

(β=0.275; t=4.966, p<0.001). Finally, community

organisation have a significant impact on

satisfaction (β=0.499; t=10.910, p<0.001). See

Figure 2.

Community

participation

R2=.35

Community

organisation

Community

integration

R2=.60

Community

satisfaction

.401

a

.405

a

.204

a

.327

a

.275

a

.499

a

a

p < 0.001,

b

p < 0.01,

c

p < 0.05, ns = not significant (based on

t(499), one-tailed test)

Figure 2: Main effects model. Results.

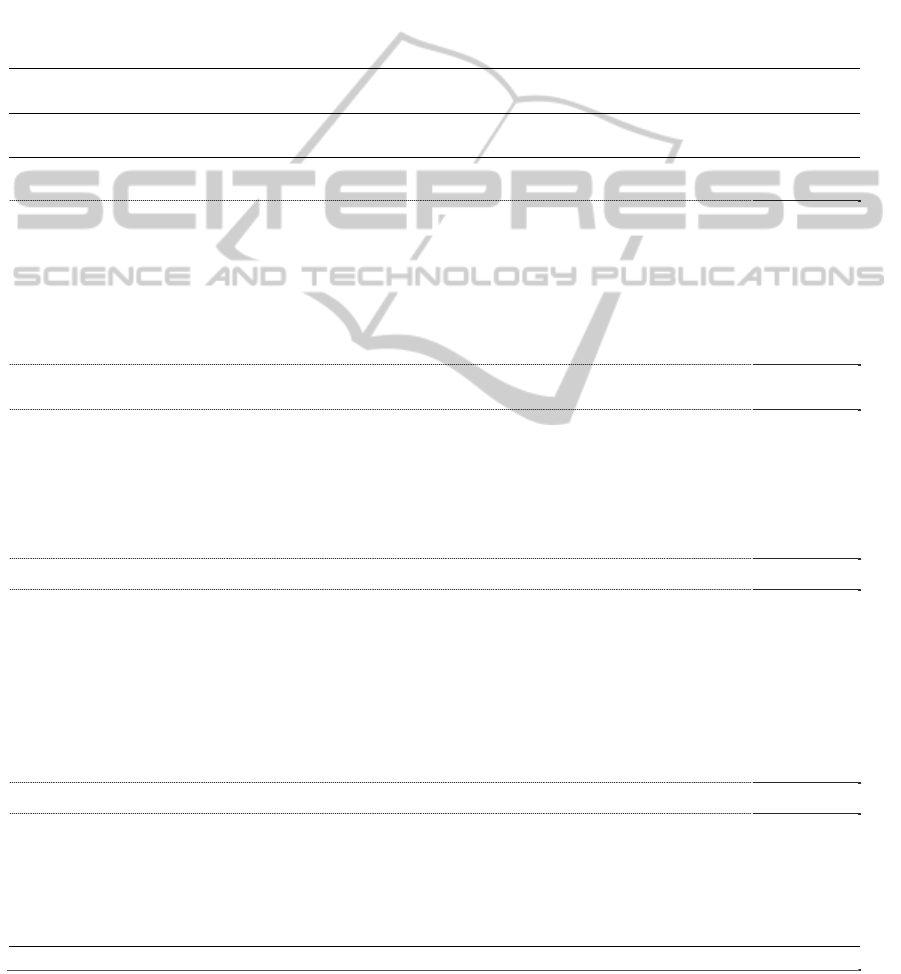

The interaction effects were also included, in

addition to the main effects model - see Figure 3. As

in regression analysis, the predictor and moderator

variables are multiplied to obtain the interaction

terms. According to Chin et al. (2003), product

indicators are developed by creating all possible

products from the two sets of indicators and the

standardising of the product indicators is

recommended. However, in the presence of

significant interaction terms involving any of the

main effects, no direct conclusion can be drawn

from these main effects alone (Aiken and West

1991). In particular, the interaction effects were of -

0.092 -community organisation * routinisation

community integration- (t=1.909, p<0.05), and 0.084

-satisfaction * routinisation community

integration- (t=1.911, p<0.05).

Therefore, Hypotheses H7 and H8 were

supported. Higher routinisation reduces the impact

of community organisation on integration, whereas

routinisation increases the impact of satisfaction on

integration.

Community

participation

R2=.35

Community

organisation

Community

integration

R2=.63

Community

satisfaction

Routinisation

.401

a

.357

a

.160

b

‐.092

c

.301

a

.084

c

.185

a

.275

a

.499

a

a

p < 0.001,

b

p < 0.01,

c

p < 0.05, ns = not significant (based on

t(499), one-tailed test)

Figure 3: Interaction effects model. Results.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Our research focused on the association between

community satisfaction and PCS by studying the

moderating effects of routinised behaviours –i.e., the

interaction effects model. Our results provided

strong support for the arguments that community

satisfaction leads the Tuenti member into developing

a growing community participation and integration.

In particular, routinised behaviours predispose

members to a higher influence of community

satisfaction on community integration, whereas the

higher routinised behaviour results in less influence

of community organisation on integration. Different

members’ segments and their post-adoption

behaviours will, therefore, play an interaction role in

affecting the influence of satisfaction (in terms of an

overall assessment of psychosocial aspects of a

relationship between the member and the other

community members) and community organisation

(in terms of support needs and resources available to

the individual) on affective commitment.

Hence, community organisation reduces its

influence on integration once interactions with the

SNS are habitual and, consequently, fulfilling and

easy. On the contrary, less routinised members tend

to engage in an SNS but in a limited way, preferring

to feel that they are being supported by their

community, thus reducing the uncertainty of the

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

462

relationship with it. Furthermore, enhancing

customer satisfaction can be seen as important

initiatives that promote routinised members’

integration and avoid consideration of competitive

SNS. Higher satisfaction will not only increase

members’ tendency to recommend their SNS to

other members but also repeat patronising their SNS

(cf. Lam et al. 2004, Sánchez-Franco, 2009). In this

regard, future research will analyse the formation

and maintenance of social capital. How to maintain

and intensify the number of members and posts

remains a problem. If not gratified and involved

properly, members lose interest and eventually

reduce their level of interaction. That is to say,

identifying main determinants of PCS will be the

goals of our future research. In particular, we will

investigate the roles of individual differences in

building PCS.

REFERENCES

Aiken, Leona S., West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression:

Testing and interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park,

CA: Sage Publications.

Baym, N. (1997). Interpreting Soap Operas and Creating

Community: Inside an Electronic Fan Culture. In

Keisler, S. (Ed.), Culture of the Internet (pp. 103-120).

Manhaw, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Blanchard, A. L. (2007). Developing a Sense of Virtual

Community Measure. CyberPsychology & Behavior,

10(6), 827-830.

Blanchard, A. L. (2008). Testing a Model of Sense of

Virtual Community. Computers in Human Behavior,

24(5), 2107-2123.

Blanchard, A. L., Markus, M. L. (2004). The Experienced

Sense of a Virtual Community: Characteristics and

Processes. The DATA BASE for Advances in

Information Systems, 35(1), 65-79.

Blanchard, A. L., Markus, M. L. (2007). Technology and

Community Behavior in Online Environments .In

Steinfield, C., Pentland, B. T., Ackerman, M.,

Contractor, N. (Eds), Communities and Technology

2007: Proceedings of the Third Communities and

Technologies Conference (pp. 323-350). Michigan

State University, Springer.

Casaló, L., Flavián, C., Guinalíu, M. (2007). The Impact

of Participation in Virtual Brand Communities on

Consumer Trust and Loyalty: The Case of Free

Software. Online Information Review, 31(6), 775–792.

Cooper, R. B., Zmud, R.W. (1990). Information

Technology Implementation Research: A

Technological Diffusion Approach. Management

Science, 36(2), 123-139.

Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of Long-Term

Orientation in Buyer-Seller Relationships. Journal of

Marketing, 58(2), 1-19.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J.-B, Scheer, L.K., Kumar N.

(1996). The Effects of Trust and Interdependence on

Relationship Commitment: A Trans-Atlantic Study.

International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13(4),

303-317.

Gustafsson, A. Johnson, M., Roos, I. (2005). The Effects

of Consumer Satisfaction, Relationship Commitment

Dimensions, and Triggers on Consumer Retention.

Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 210-218.

Herrero, J., Gracia, E. (2007). Measuring Perceived

Community Support: Factorial Structure, Longitudinal

Invariance, and Predictive Validity of the PCSQ

(Perceived Community Support Questionnaire).

Journal of Community Psychology, 35(2), 197–217.

Koh, J., Kim, Y.-G. (2004). Knowledge Sharing in Virtual

Communities: An e-Business Perspective. Expert

Systems with Applications, 26(2), 155-166.

Lam, S. Y., Shankar, V., Erramilli, M. K., Murthy, B.

(2004). Customer Value, Satisfaction, Loyalty, and

Switching Costs: An Illustration from a Business-to-

Business Service Context. Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 32(3), 293-311.

Loewenfeld, F. (2006). Brand Communities—

Erfolgsfaktoren und ökonomische Relevanz von

Markeneigenschaften. Deutscher Universitäts-Verlag:

Wiesbaden.

McMillan, D. W. Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of

Community: A Definition and Theory. Journal of

Community Psychology, 14(1), 6-23.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., Will, A. (2008). SmartPLS 2.0

(Beta). University of Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany,

2005, available at: http://www.smartpls.de (accessed

March 20).

Rothaermel, F. T., Sugiyama, S. (2001). Virtual Internet

Communities and Commercial Success: Individual and

Community-Level Theory Grounded in the Atypical

Case of TimeZone.com. Journal of Management

27(3), 297–312.

Saga, V., Zmud, R. W. (1994). The Nature and

Determinants of IT Acceptance, Routinization, and

Infusion. In Levine, L. (Ed.), Diffusion, Transfer, and

Implementation of Information Technology (pp. 67-

86). New York: North-Holland.

Sánchez-Franco, M. J. (2009). The Moderating Effects of

Involvement on the Relationships between

Satisfaction, Trust and Commitment in e-Banking,

Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23(3), 247-258

Sánchez-Franco, M. J., Roldán, J. L. (2010). Expressive

Aesthetics to Ease Perceived Community Support:

Exploring Personal Innovativeness and Routinised

Behaviour as Moderators in Tuenti. Computers in

Human Behavior, 26(6), 1445–1457.

Sánchez-Franco, M. J., Rondan Cataluña, F. J. (2010).

Virtual Travel Communities and Customer Loyalty:

Customer Purchase Involvement and Web Site Design.

Electronic Commerce Research and Applications,

9(2), 171-182.

Schwarz, A. Chin, W. W. (2007). Looking forward:

Toward an Understanding of the Nature and Definition

POST-ADOPTION BEHAVIOUR, COMMUNITY SATISFACTION AND PCS - An Analysis of Interaction Effects in the

Tuenti Community

463

of IT Acceptance. Journal of the Association for

Information Systems, 8(4), 230–243.

Sundaram, S., Schwarz, A., Jones, E., Chin, W. W. (2007).

Technology Use on the Front Line: How Technology

Enhances Individual Performance. Journal of the

Academy of Marketing Sciences, 35(1), 101–112

Welbourne, J. L., Blanchard, A. L., Boughton, M. D.

(2009). Supportive Communication, Sense of Virtual

Community and Health Outcomes in Online Infertility

Groups. In C&T’09 (pp. 31-40). Pennsylvania, USA:

University Park.

Wellman, B., Gulia, M. (1999). Net Surfers don’t Ride

Alone: Virtual Communities as Communities. In

Wellman, B. (Ed.), Networks in the global village:

Life in contemporary communities. Westview Press:

Boulder, CO.

APPENDIX

Table 2: Measurement model. Main effects model.

a. Individual item reliability-individual item loadings. Construct reliability and convergent

validity coefficients

Latent Dimension Loadings

a

c

AVE

CO. Community organisation

CO1. I could find people that would help me feel better 0.812 0.924 0.710

CO2. I could find someone to listen to me when I feel down 0.863

CO3. I could find a source of satisfaction for myself 0.871

CO4. I could be able to cheer up and get into a better mood 0.873

CO5. I could relax and easily forget my problems 0.791

CI. Identification with virtual community (i.e., community

integration)

CI1. My affective bonds with my Tuenti community are the

main reason why I continue to use its service

0.886 0.923 0.750

CI2. I enjoy being a member of my Tuenti community 0.918

CI3. I have strong feelings for my Tuenti community 0.827

CI4. In general, I relate very well to the members of my

Tuenti community

0.831

CP. Community participation

CP1. I participate in order to stimulate my Tuenti

community

0.879 0.911 0.672

CP2. I take part actively in activities in my Tuenti

community

0.783

CP3. I take part in social groups in my Tuenti community 0.767

CP4. I respond to calls to support my Tuenti community 0.779

CP5. I take part actively in socio-recreational activities in

my Tuenti community

0.883

CS. Satisfaction

CS1. In general terms, I am satisfied with my experience in

my Tuenti community

0.907 0.940 0.839

CS2. I think that I made the correct decision to use my

Tuenti community

0.917

CS3. I have obtained several benefits derived from my

participation in my Tuenti community

0.924

a

All loadings are significant at p<0.001- (based on t

(

499

)

, two-tailed test)

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

464

Table 2: Measurement model. Main effects model. (cont.)

b. Discriminant validity coefficients

CO CI CP CS

CO

0.843

CI

0.585 0.866

CP

0.538 0.669 0.820

CS 0.499 0.621 0.475 0.916

Note: Diagonal elements are the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) between the constructs and their measures.

Off-diagonal elements are correlations between constructs

i

Our theoretical background manifested the appropriateness of incorporating routinised behaviour into our main research model to identify

interaction effects. The main effects model was thus re-evaluated, including routinisation-based indicators. The individual reflective-item

reliability, the composite reliabilities for the multiple reflective indicators, and convergent and discriminant validities were well over the

recommended acceptable level.

POST-ADOPTION BEHAVIOUR, COMMUNITY SATISFACTION AND PCS - An Analysis of Interaction Effects in the

Tuenti Community

465