WEB-BASED SYSTEM FOR AUTOMATICALLY COLLECTING

INFORMATION ABOUT LOCATIONS OF VOLUNTEER

ACTIVITIES OF CITIZEN GROUPS

Akira Hattori and Haruo Hayami

Department of Information Media, Kanagawa Institute of Technology, Atsugi, Japan

Keywords:

Volunteer activities, Automatic collection, Postal address, Web, Map.

Abstract:

A large number of citizen groups, many of which work in a community setting, publish information about

their missions and activities on their Websites. However, it is difficult to understand where and what types of

activities they do because such information is distributed throughout the Web. We show how citizen groups

are currently using maps on their Websites and propose a system for automatically collecting information

from their Websites about locations of their volunteer activities. Our system selects numerous URLs of citizen

group Websites and extracts information about locations of volunteer activities from each group based on the

content and structure of each page on the site. We developed and evaluated a prototype system and found

that our proposed system has great potential for understanding volunteer activities of citizen groups in a local

community.

1 INTRODUCTION

Recently, citizen groups have been playing an im-

portant role in providing solutions to various needs

of citizens and challenges facing societies worldwide

(Salamon et al., 2003). To conduct their volunteer ac-

tivities more effectively and to strengthen their foun-

dations, it is important for citizen groups to gain the

trust and support of their potential supporters, who are

individuals, governments, and businesses. They are

also working in an era of greater demands, fewer re-

sources, and increased competition. Information and

Communication Technology holds the promise of ad-

dressing these challenges, and many groups publish

information about their missions, activities, and their

results on the Web (Hackler and Saxton, 2007). On

the other hand, many people who want to participate

in or support volunteer activities of citizen groups

search for such information using the Web. This has

led to the Web being an important tool for citizen

groups and their potential supporters to publish and

collect information.

However, because each group publishes informa-

tion on its own Website, general information about

volunteer activities is distributed throughout the Web.

This causes difficulties in understanding where and

what types of activities are done by certain citizen gr-

oups. These difficulties can be overcome by aggre-

gating such information published by these groups on

their Websites. In addition, maps are useful for them

to publish information (Craig and Elwood, 1998).

However, to our knowledge, little is known about how

citizen groups are using maps on their Websites.

Therefore, we show how citizen groups in Japan

currently use maps on their Websites, and propose a

system for automatically collecting information about

locations of volunteer activities from their Websites

by taking such map usage into consideration. With

our system, potential supporters who want to partici-

pate in or support volunteer activities can understand

where and what types of activities are performed by

such groups in an easy-to-understand map. This will

lead to increased citizen involvement and coopera-

tion.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, we briefly discuss related work. In Section

3, we show how citizen groups currently use maps

on their Websites. In Section 4, we describe our pro-

posed system, followed by its evaluation and discus-

sion. Finally, we give our conclusion in Section 6.

539

Hattori A. and Hayami H..

WEB-BASED SYSTEM FOR AUTOMATICALLY COLLECTING INFORMATION ABOUT LOCATIONS OF VOLUNTEER ACTIVITIES OF CITIZEN

GROUPS.

DOI: 10.5220/0003336805390546

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2011), pages 539-546

ISBN: 978-989-8425-51-5

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Citizen Group Websites and Online

Databases

Over the past ten years numerous attempts have been

made to assess how citizen groups use their Websites

using content analysis. Some studies involved eval-

uating such Websites from the viewpoint of commu-

nication and fundraising practices (Kent and White,

2001) (Waters, 2007). There have also been several

studies on how Web 2.0 technologies, such as Weblog

and social networking sites, were being used by citi-

zen groups to advance their missions and programs

(Waters et al., 2009) (Greenberg and MacAulay,

2009). However, as far as we know, how citizen

groups use maps on their Websites has never been ex-

amined. We show such usage based on citizen group

Websites research. A large number of citizen groups

work in a local community setting, and Web mapping

services, such as Google Maps and Yahoo! Maps, are

freely available (Hudson-Smith et al., 2007). Such

mapping services hold the promise of providing an

opportunity for using maps on Websites for citizen

groups, especially, small ones, which generally have

limited financial and human resources. Many groups

are small in Japan. Therefore, it is important to ex-

plore how these citizen groups use maps on their Web-

sites.

A variety of online databases of citizen

groups have been developed by various orga-

nizations on the Web, for example, GuidStar

(http://www2.guidestar.org/), The Chronicle of

Philanthropy (http://www.philanthropy.com/), and

Imagine Canada (http://www.imaginecanada.ca/).

These databases store basic information such as

names, locations of main offices, and missions and

programs, and make it available to the public. Some

databases allow registered groups to update their

information. However, the information stored in

such databases is basic and are typically textual

documents. Therefore, they do not provide an easy

environment to understand where and what types

of activities are performed by citizen groups. In

contrast, our proposed system aggregates location

information of their volunteer activities distributed

on their Websites and puts it onto a map.

2.2 Detection of Geographic Location

Information on the Web

It has long been recognized that there is a large

amount of geographic location information on the

Web. Many Web pages have one or more types of

geographic location information. However, current

search engines often produce results of geograph-

ically unrelated pages for queries containing some

kind of geographic term. Considerable attention

has been on geographic-oriented keyword searches.

Many approaches have been proposed for detecting

geographic location information on the Web (McCur-

ley, 2001), (Amitay et al., 2004), (Clough, 2005), and

(Wang et al., 2005). They identify and extract infor-

mation from Websites from around the world. Jun-

yan et al. (Junyan et al., 2000) discuss how to au-

tomatically estimate the geographical scope of Web

resources. Ahlers and Boll (Ahlers and Boll, 2007)

and Gao et al. (Gao et al., 2006) proposed several ge-

ographically focused crawling strategies for collect-

ing Web pages related to the specified geographic re-

gions. There are also systems for automatically cre-

ating a detailed gazetter (Goldberg et al., 2009) and

(Martins et al., 2009), which is a unified repository

of geographic information, from geographic location

information on the Web. The system developed by

Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2007) visualizes RSS feeds

containing geographic location information on a map.

Current systems, including those mentioned

above, collect geographic location information from

Websites from around the world or specific informa-

tion sources such as the RSS feeds specified by a user.

However, to our knowledgethere is no comprehensive

collection of links to citizen group Websites. There-

fore, it is necessary to find such links from numerous

Websites and to extract information about locations

of volunteer activities from each group, and current

systems are inadequate for doing this. Our system is

characterized by selecting a Website for each citizen

group and extracting information about locations of

volunteer activities from the site based on the group’s

basic information, content, and structure of each page

on the site.

3 HOW CITIZEN GROUPS

CURRENTLY USE MAPS

ON THEIR WEBSITES

3.1 Methodology

Maps are useful for citizen groups working in a com-

munity setting to publish information. To understand

how citizen groups currently use maps on their Web-

sites, we examined two questions before designing

our system: (1) What types of maps are used by these

groups? and (2) What kind of information do they

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

540

Figure 1: Map types for each type of map content.

publish using these maps? We refer to questions (1)

and (2) as ”map type” and ”map content”, respec-

tively.

Citizen groups were drawn from ”npo hiroba”,

which is one of the largest online databases in Japan

and is available at http://www.npo-hiroba.or.jp/. We

selected groups that have main offices in Kanagawa

and have Websites. We analyzed the Websites of 297

groups from June 6 to 23, 2010.

3.2 Results

The map content of citizen group Websites are di-

vided into three purposes: for showing the locations

of their main offices, locations of their programs and

services they regularly provide, and sites of special

events they hold. Figure 1 illustrates what types of

maps are used for each type of the map content. Most

of the maps for showing the main offices are hand

drawn using word processing programs and map cre-

ation tools. About 15% of the groups we examined

use Web mapping services, and many of them do this

to show the locations of their main offices and their

programs and services. About one-tenth of the groups

use maps to show their special events, and about half

of them are links to external Web pages containing

maps.

3.3 Discussion

About half the groups we examined use maps to show

the locations of their main offices and the places

where they provide their programs and services. One

of the purposes of using a map on a Website is to show

locations to visitors. For this purpose, many groups

are likely to use hand drawn maps containing only

landmark buildings and large intersections rather than

detailed maps. However, because each group man-

ages its own Website, information about their volun-

teer activities are distributed over many sites through-

out the Web. This causes difficulties in understand-

ing where and what types of activities are performed

by citizen groups. It is effective for those who want

to search for citizen groups on the Web to aggregate

these two types of geographic location information

about their volunteer activities distributed throughout

the Web into a map. A street or postal address is the

most common way to refer to a location (Himmel-

stein, 2005). In addition, addresses are found on many

of the groups’ Web pages containing maps showing

the locations of their main offices and programs and

services. Thus, our proposed system automatically

collects addresses as information about locations of

volunteer activities done by citizen groups from their

Websites and puts this information onto a map.

4 AUTOMATICALLY

COLLECTING LOCATIONS

OF VOLUNTEER ACTIVITIES

4.1 Outline of Our System

As mentioned above, there is no collection of links

to citizen group Websites, and postal addresses are

found on many of the groups’ Web pages containing

maps. Thus, our system has two main functions. One

is to find the addresses (URLs) of such Websites from

numerous sites throughout the Web, and the other is

to extract postal addresses from these Websites.

The overall flow of our system are as follows. (1)

The system collects basic information about citizen

groups such as names, location of main offices, and

mission and activity areas from an online database

of them on the Web, attaches geographic coordinates

(latitude and longitude) corresponding to the location,

and stores the information in our system’s database,

which is referred to as the basic information database.

(2) Next, it collects URLs of citizen group Websites

using a Web search engine and selects one for each

group. (3) Then, it extracts information about lo-

cations of volunteer activities, which is a postal ad-

dress in our system, and maps used from each Web-

site and stores the information in two of our system’s

databases, referred to as the first location informa-

tion database of volunteer activities and map meta-

data database, respectively. The system attaches ge-

ographic coordinates corresponding to the extracted

address as well. (4) Then it applies some filters to

the extracted addresses based on the structure of the

Web page such as the address and presence or absence

of a map, and stores the resulting addresses in an-

other database of our system, referred to as the second

location information database of volunteer activities.

(5) Finally, it shows geographic location information

stored in the databases on a map using a Web mapping

WEB-BASED SYSTEM FOR AUTOMATICALLY COLLECTING INFORMATION ABOUT LOCATIONS OF

VOLUNTEER ACTIVITIES OF CITIZEN GROUPS

541

service. The following section explains each step in

detail.

4.2 System Functions

4.2.1 Collecting Basic Information

Our system uses the ”NPO portal” site as the on-

line database of citizen groups to collect basic in-

formation such as their names and locations of

main offices. The site is managed by the Cabi-

net Office of Japan and available at http://www.npo-

homepage.go.jp/portalsite.html. The system searches

for citizen groups on the site by location of their main

offices, and parses the resulting HTML document

to collect basic information about the citizen groups

linked from the document. After that, it converts the

location of the main office contained in the basic in-

formation to geographic coordinates, which are lati-

tude and longitude, using the geocoding functionality

of a Web mapping service. Finally, it stores the infor-

mation in the basic information database.

4.2.2 Collecting and Selecting URLs of Citizen

Group Websites

To collect URLs of citizen group Websites, our sys-

tem first puts their names and ”NPO, or ’specified

nonprofit corporation’”, as keywords in the query of a

Web search engine, which is the Google search in our

system. The system uses the top three search results

as candidates for the URL of each group’s Website.

Then, it applies the following filters to these candi-

dates:

1. If more than two URLs have the same host and a

path starting with the same directory of the server,

they are regarded as indicating an online database

of citizen groups and eliminated from the candi-

dates. They all start with ”scheme://host/path/.”

2. If one of the path elements of a URL is an e-

mail address, a postal code (three-digits hyphen

four-digits in Japan) or a telephone number (three-

digits hyphen three-digits hyphen four-digits, etc.

in Japan), it is regarded as indicating an online

database and eliminated from the candidates.

3. If one of the path elements of a URL is ”bbs”,

which is short for bulletin board system, or ”ml”,

which is short for mailing list, it is eliminated

from the candidates. This is because many bul-

letin board systems and mailing lists are used to

communicate among members and supporters of

citizen groups.

4. If the title of the Website at a URL for a group do

not contain the group’s name, the URL is elimi-

nated from the candidates.

After applying these filters, our system selects the

URL with the highest ranking for each group as its

Website.

4.2.3 Extracting Addresses and Maps from

Websites

First, to extract addresses and maps from citizen

group Websites, our system searches within the Web-

site of the URL selected for each group using a Web

search engine. Then, the system executes the follow-

ing process for each of the resulting Web pages.

As a preprocessing to extract addresses and maps

from each page, our system converts the HTML doc-

ument to XML with HTML Tidy and loads it as a tree

of nodes, which is commonly referred to as a docu-

ment object model (DOM) tree. After that, our system

traverses the tree from its root.

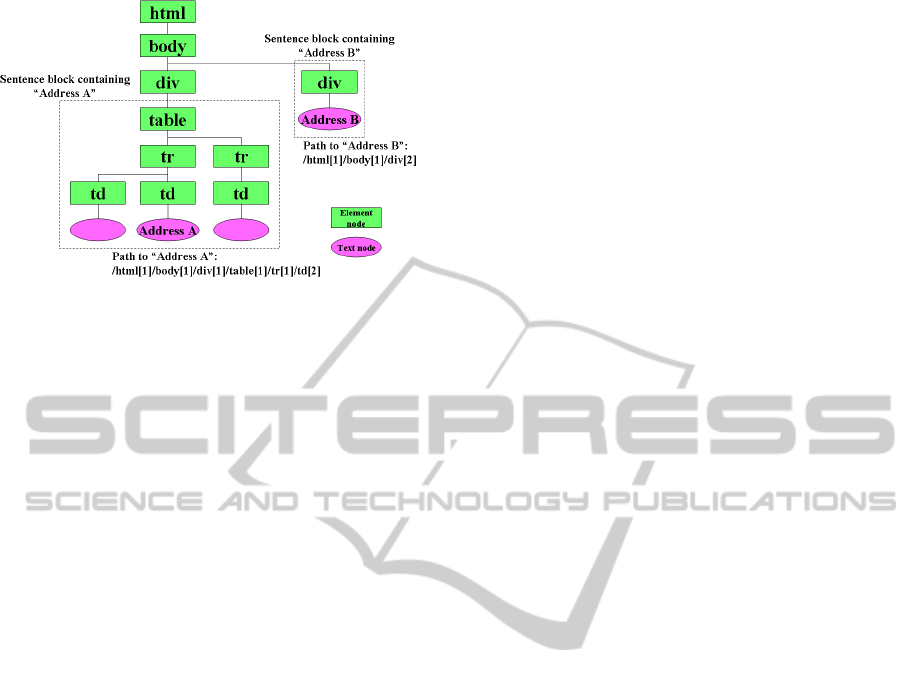

When our system moves to the text node, it ex-

tracts a set of addresses from the node’s value based

on regular expression matching of an address and

converts each extracted address to geographic coordi-

nates using the geocoding functionality of Web map-

ping services. If an address is convertedto geographic

coordinates, it is stored in the first location informa-

tion database of volunteer activities together with the

coordinates. The first database also stores the path ex-

pression to traverse the tree from its root down to the

processing text node. Moreover, it stores the values

of all text nodes contained in a sentence block. As

shown in Figure 2, we defined a sentence block as a

node corresponding to an HTML block element, such

as <DIV>, <TABLE>, <P>, <BODY>, which is

first encountered in moving up the tree from the text

node towards its root. If the value of a text node is a

sentence, our system does not extract any addresses.

To determine whether a value is a sentence or not, the

system uses punctuation marks.

On the other hand, for extracting maps, our system

checks if a node satisfies either of the following con-

ditions based on the characteristics of the maps used

on citizen group Websites.

1. When the name of the processing node is ”img”,

which is an <IMG> tag, and the value of the src

attribute contains a word like ”map” or ”tizu” in

the file name of the image. ”Tizu” means ”map”

in Japanese.

2. When it is ”a” or ”iframe”, which are <A> and

<IFRAME> tags, respectively, the value of the

href or the src attribute references a Web mapping

service with a specific location.

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

542

Figure 2: Example of sentence block.

When a map is found, our system stores the map’s

metadata in the map metadata database. The metadata

consists of the value of an href or a src attribute and

the path expression to traverse the tree from its root to

the node containing the map.

4.3 Address Filtering

Our system applies filters to addresses stored in the

first location information database of volunteer activ-

ities, and stores the resulting ones in the second one.

The filters are as follows.

1. When none of addresses extracted from a Web-

site of a citizen group correspond with the loca-

tion of its main office stored in the basic informa-

tion database, it is assumed that the selected URL

is not the one for the group, namely, the correct

URL is not selected. In this case, our system does

not store all the addresses extracted from the Web-

site in the second database.

2. When there are different addresses at the same po-

sition in each tree structure for many pages on a

citizen group Website, it is assumed that its URL

selected using our system is an online database. In

our system, the same position means that the path

expression to a text node containing an address in

a Web page on a Website is the same as that in an-

other page containing the address of the Website.

In this case, our system does not store all the ad-

dresses extracted from the Website in the second

database.

If a page containing an address also has a map

after applying these filters, our system stores the ad-

dress in the second database. Therationale is based on

the fact that addresses are found on many pages with

maps on the citezen group Websites we examined, as

shown in Section 3.

There are also groups that do not use maps on

their Websites. Therefore, when the text values within

the sentence block corresponding to an address con-

tains date expressions such as ”every week” or ”every

month” and words indicating the day of the week, our

system stores the address in the second database as

well. We emphasize regular activities before irregu-

lar ones, such as a seminar, and set such words and

expressions as a condition for storing addresses in the

second database.

However, when the same address appears at the

same position in each tree structure for many pages on

a citizen group Website, it is assumed that the address

is contained in the common menu, header, or footer of

pages on the Website. If a page contains two or more

addresses, our system does not store those appearing

at such positions in the second database.

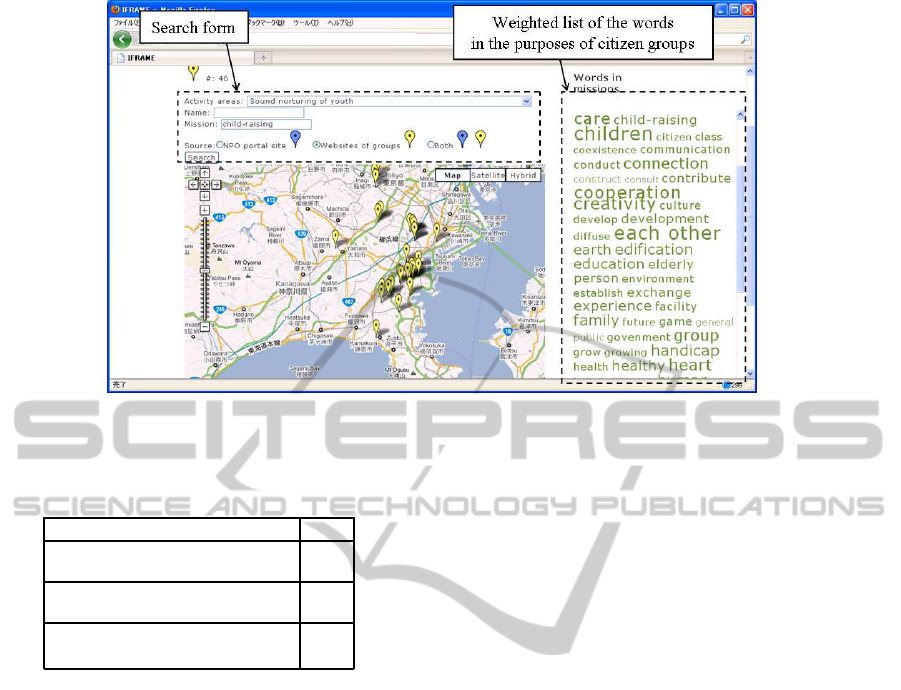

4.4 Prototype System

We developed a prototype system to collect informa-

tion about locations of volunteer activities for 2658

citizen groups in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. The

prototype displays the locations of the main offices

stored in the basic information database and the ex-

tracted addresses from citizen group Websites stored

in the second location information database of volun-

teer activities on a map using Google Maps. Users

can search for citizen groups by their names, activ-

ity areas, and missions. To help users do this, the

prototype performs morphological analysis of citizen

group missions in the basic information database and

displays a weighted list of the words in the missions

in accordance with the frequency of their appearance.

Each word in the list is a hyperlink that leads to a

search by missions. Figure 3 illustrates a search for

”Sound nurturing of youth” in the activity area and

”child-raising” in the mission. In this figure, extracted

addresses from the Websites of the resulting citizen

groups are shown on the map.

5 EVALUATION

AND DISCUSSION

5.1 Accuracy of Selecting URLs

of Citizen Group Websites

We first evaluated the accuracy of selecting URLs of

citizen group Websites. We compared URLs selected

with our proposed system with those of the Websites

we examined to understand how citizen groups cur-

rently use maps. Because 5 of the examined 297

groups had not been stored in the ”NPO portal” site,

we compared the URLs of 292 group Websites. As

WEB-BASED SYSTEM FOR AUTOMATICALLY COLLECTING INFORMATION ABOUT LOCATIONS OF

VOLUNTEER ACTIVITIES OF CITIZEN GROUPS

543

Figure 3: Map displaying search results.

Table 1: Result of selecting URLs of citezen group Web-

sites.

Correct or incorrect #

Number of URLs

our system correctly selected

168

Number of URLs

not correctly selected

61

Number of citizen groups

that selected no URL

63

listed in Table 1, the URLs of Websites for 168 out of

the 292 groups were correctly selected. The recall ra-

tio was 57.5% and the precision ratio was 73.4%. The

reasons why our system could not select the correct

URL are as follows.

• There were groups with the same or almost the

same name.

• A Website was moved to another server.

• A Weblog, not a Website, of a citizen group was

selected.

We need to solve these problems to improve the

recall ratio.

For all 2658 citizen groups, our system selected

URLs of Websites for 1271 groups. Taking the pre-

cision ratio, which is 73.4%, into consideration, the

URLs of Websites for about 930 groups could be

correctly selected. According to the research con-

ducted by the Cabinet Office of Japan, 59.0% of cit-

izen groups, all of which are specified as nonprofit

corporations in Japan, have their own Websites. Con-

sequently, in Kanagawa Prefecture, about 1570 of the

2658 groups have their own Websites, and it can be

assumed that the 930 groups will show a precision ra-

tio of 59.5%. This is a promising result because there

is no collection of links to citizen group Websites.

5.2 Evaluation of Address Extraction

We evaluated address extraction performance of our

proposed system. We used the 292 citizen groups

discussed in the previous section. Our system cor-

rectly selected URLs of Websites for 168 groups as

discussed in the preceding section, and the system

stored addresses from 148 of the 168 group Websites

in the first database. Locations of main offices were

extracted from 106 of the 148 Websites and other lo-

cations were from 117 Websites. On the other hand,

the system could not select the correct URLs of Web-

sites for 61 groups and stored addresses from 37 out

of the 61 Websites in the first database. Locations of

main offices were extracted from 14 of the 37 Web-

sites and other locations were from 31 Websites.

In addition, the system extracted maps from 111

of the 168 group Websites. On the other hand, it ex-

tracted maps from 17 of the 61 group Websites.

One of the simplest filters for storing addresses in

the second database is one in which at least one of the

addresses extracted from a Website of a citizen group

corresponds with the location of the group’s main of-

fice stored in the basic information database. Thus,

to evaluate our proposed system of storing addresses

in the second database, we compared our system in

which a filter of a Web page containing an address

has maps or date expressionswith one in which a filter

was not applied. We refer to these two filters as pro-

posed and simple, respectively. The results are listed

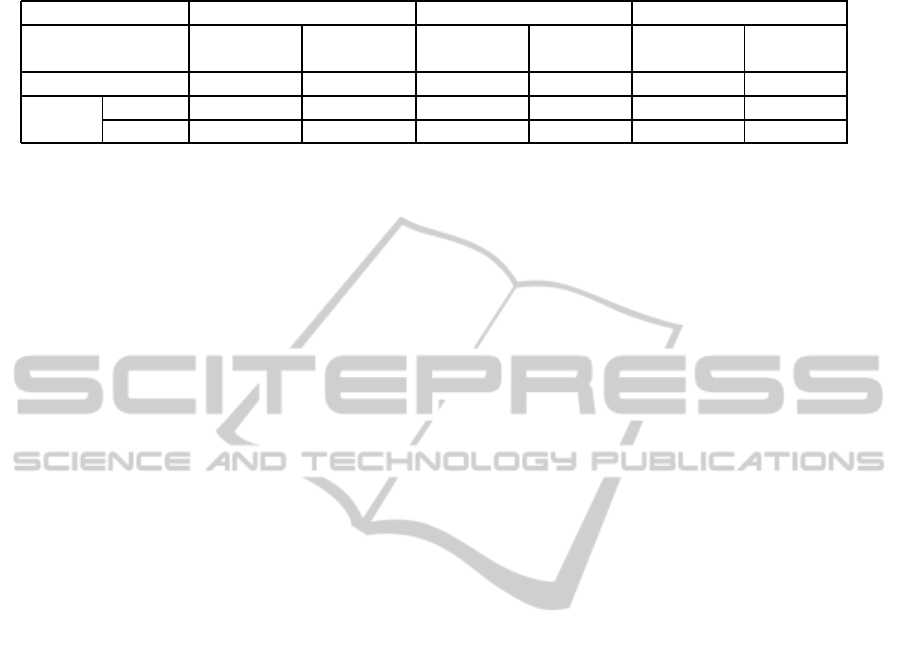

in Table 2.

With the simple filter, our system stored addresses

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

544

Table 2: Number of citizen groups stored in first and second databases.

Location of main office (a) Other locations (b) Address (a or b)

Correct, or

incorrect

Correct

(%, N=168)

incorrect

(%, N=61)

Correct

(%, N=168)

incorrect

(%, N=61)

Correct

(%, N=168)

incorrect

(%, N=61)

First database 106(63.1%) 14(23.0%) 117(69.6%) 31(50.8%) 148(88.1%) 37(60.7%)

Second Proposed 49(29.2%) 3(4.9%) 38(22.6%) 2(3.3%) 63(37.7%) 4(7.5%)

database Simple 101(60.1%) 14(23.0%) 70(41.7%) 8(13.1%) 101(60.1%) 14(23.0%)

extracted from Websites for 101 out of 148 groups,

of which Website URLs were correctly selected, in

the second database, which was 60.1%. On the other

hand, with the proposed filter, the system stored ad-

dresses from 63 Websites, which was 37.7%. For the

37 groups in which the Website URLs were not cor-

rectly selected, our system stored addresses from 14

Websites in the second database with the simple filter,

which was 60.7%. With the proposed filter, however,

our system stored addresses from 4 Websites, which

was 7.5%. URLs of 3 out of the 4 Websites were pre-

fixed with ”www” to each of the corresponding cor-

rect URLs or vice versa, and their IP addresses were

the same. Thus, with the proposed filter, very few ad-

dresses were stored from Websites that were not cor-

rectly selected in the second database.

5.3 Potential of Our System

We received the following positive comments from

five citizen group members who participated in a pre-

liminary evaluation.

• This system is practical because a map is intu-

itively understandable and makes it possible to or-

ganize information into each location.

• This system is useful when we are asked for ad-

vice, for example, to send direct mail to groups

working to improve the welfare of citizens.

• We can use the system when we want to do some-

thing for the local community but we do not have

enough resources such as people and skills.

• I have never seen such a system before. This sys-

tem can be used as an information source since we

can see how many groups are in an area.

• Plotting locations of volunteer activities on a map

is easy-to-understand because they are seen.

We also received the following suggestions.

• It is necessary for activities, such as for the envi-

ronment and urban development, to be in different

colors on the map.

• I am interested in a map showing locations of citi-

zen groups; however, it is more important to show

their activities.

• In Japan, sometimes a location of a main office

is one’s home. Therefore, it will be necessary to

provide a map with that in mind.

• The system can be improved when local informa-

tion, such as shopping and sightseeing, is com-

bined with information about volunteer activities

on the map.

• I’m afraid that the system might cause informa-

tion overload, and it may be difficult to keep the

information updated.

• When a location changes through time, for exam-

ple event information, it may be difficult to under-

stand the change on the map.

These positive comments indicate that our system

with a function for collecting locations of volunteer

activities done by citizen groups from their Websites

has great potential for understanding their volunteer

activities in a local community. Although requiring

a combination of an address and map decreases the

recall ratio of address extraction, it is effective for

the condition that in Japan, sometimes a location of

a main office is one’s home. This is because one of

the purposes of using a map on a Website is to show a

location to visitors. On the other hand, it was pointed

out that information about volunteer activities them-

selves was not adequately shown. Thus, we need

to develop methods for collecting more information

from citizen group Websites and to display and en-

able one to search for such information on a map.

6 CONCLUSIONS

We showed how citizen groups in Japan currently use

maps on their Websites, and proposed a system for

automatically collecting locations of their volunteer

activities from their Websites. We also developed and

evaluated a prototype system and found that collect-

ing such locations and displaying them on a map has

great potential for understanding volunteer activities

of citizen groups in a local community.

Future work includes enhancing functionality of

our system based on the results from evaluating the

WEB-BASED SYSTEM FOR AUTOMATICALLY COLLECTING INFORMATION ABOUT LOCATIONS OF

VOLUNTEER ACTIVITIES OF CITIZEN GROUPS

545

prototype system. We also need to evaluate our sys-

tem based on a broader implementation test. Further-

more, it is important to see how the system will have

an effect on citizen group Websites and their activi-

ties.

REFERENCES

Ahlers, D. and Boll, S. (2007). Geospatially focused web

crawling. Datenbank-Spektrum, 7(23):3–12.

Amitay, E., Har’El, N., Sivan, R., and Soffer, A. (2004).

Web-a-where: geotagging web content. In Proceed-

ings of the 27th annual international ACM SIGIR con-

ference on Research and development in information

retrieval, pages 273–280.

Chen, Y., Fabbrizio, G. D., Gibbon, D., Jana, R., Jora, S.,

Renger, B., and Wei, B. (2007). Geotracker: Geospa-

tial and temporal rss navigation. In Proceedings of

the 16th international conference on World Wide Web,

pages 41–50.

Clough, P. (2005). Extracting metadata for spatially-aware

information retrieval on the internet. In Proceedings

of the 2005 workshop on Geographic information re-

trieval, pages 25–30.

Craig, W. J. and Elwood, S. A. (1998). How and why

community groups use maps and geographic informa-

tion. Cartography and Geographic Information Sys-

tems, 25(2):95–104.

Gao, W., Lee, H. C., and Miao, Y. (2006). Geographi-

cally focused collaborative crawling. In Proceedings

of the 15th international conference on World Wide

Web, pages 287–296.

Goldberg, D. W., Wilson, J. P., and Knoblock, C. A. (2009).

Extracting geographic features from the internet to au-

tomatically build detailed regional gazetteers. Interna-

tional Journal of Geographical Information Science,

23(1):93–128.

Greenberg, J. and MacAulay, M. (2009). Npo 2.0? explor-

ing the web presence of environmental nonprofit orga-

nizations in canada. Global Media Journal - Canadian

Edition, 2(1):63–88.

Hackler, D. and Saxton, G. D. (2007). The strategic use

of information technology by nonprofit organizations:

Increasing capacity and untapped potential. Public

Administration Review, 67(3):474–487.

Himmelstein, M. (2005). Local search: The internet is the

yellow pages. Computer, 38(2):26–34.

Hudson-Smith, A., Milton, R., Batty, M., Gibin, M., Lon-

gley, P., and Singleton, A. (2007). Public domain

gis, mapping & imaging using web-based services. In

Third International Conference on e-Social Science.

Junyan, D., Luis, G., and Narayanan, S. (2000). Computing

geographical scopes of web resources. In VLDB ’00:

Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on

Very Large Data Bases, pages 545–556.

Kent, M. L. and White, W. J. (2001). How activist orga-

nizations are using the internet to build relationships.

Public Relations Review, 27(3):263–284.

Martins, B., Manguinhas, H., Borbinha, J., and Siabota, W.

(2009). A geo-temporal information extraction ser-

vice for processing descriptive metadata in digital li-

braries. e-perimetron, 4(1):25–37.

McCurley, K. S. (2001). Geospatial mapping and naviga-

tion of the web. In Proceedings of the 10th interna-

tional conference on World Wide Web, pages 221–229.

Salamon, L. M., Sokolowski, S. W., and List, R. (2003).

Global Civil Society: An Overview. Center for

Civil Society Studies, Institute for Policy Studies, The

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Wang, C., Xie, X., Wang, L., Lu, Y., and Ma, W.-Y. (2005).

Detecting geographic locations from web resources.

In Proceedings of the 2005 workshop on Geographic

information retrieval, pages 17–24.

Waters, R. D. (2007). Nonprofit organizations’ use of the

internet: A content analysis of communication trends

on the internet sites of the philanthropy 400. Nonprofit

Management and Leadership, 18(1):59–76.

Waters, R. D., Burnett, E., Lamm, A., and Lucas, J.

(2009). Engaging stakeholders through social net-

working: How nonprofit organizations are using face-

book. Public Relations Review, 35(2):102–106.

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

546