EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH VALIDATION FOR THE USE

OF 3D IN TEACHING HUMAN ANATOMY

Nady Hoyek, Christian Collet, Aymeric Guillot

Centre de Recherche et d’Innovation sur le Sport, Université Lyon 1, Lyon, France

Patrice Thiriet, Emmanuel Sylvestre

Innovation, Conception et Accompagnement à la Pédagogie, Université Lyon 1, Lyon, France

Keywords: Anatomy, 3D, Spatial ability, Learning, Teaching.

Abstract: ICAP department of Lyon 1 university developed instructional tools based on 3 dimensional (3D)

technologies to assist human anatomy teachers. Three experimental researches aimed to validate the use of

these tools. In study 1 we searched for correlations between spatial ability tests and anatomy examination

scores. In study 2 we evaluated the effects of specific spatial ability training on anatomy examination

results. Study 3 investigated the beneficial effects of using 3D tools during a short term learning session. We

found that spatial ability is a predictor of success in learning human anatomy, however the benefits from

using 3D tools is not effective during a 2-hours learning session.

1 INTRODUCTION

The effects of Mental Rotation (MR) and spatial

abilities on the medical field have been considered

in the literature. A large body of research has

provided evidence that the spatial ability was related

to the success in anatomy learning and procedures in

laparoscopic surgery, hence highlighting the crucial

role of individual spatial ability in human anatomy

learning (Garg et al. 2001; Hegarty et al. 2007;

Keehner et al. 2004; Risucci 2002; Wanzel et al.

2003; Rochford 1985). In 2005 instructional design

tools based on three dimensional (3D) technologies

was developed in Lyon 1 university for human

anatomy teaching. Since then, 3D videos as well as

other instructional tools (3D images, interactive

PDF, course book) are used during anatomy classes.

This instructional design is scientifically tested in

several didactic studies we conducted in order to

validate the use of 3D during human anatomy

courses. Our experimental researches intended

answering three main questions:

Is there any correlation between spatial

abilities tests scores and anatomy learning

scores?

What are the effects of MR training on

learning anatomy?

Is there any positive learning effect of using

3D tools in a 2 hours class as compared to the

use of classical 2D images?

We hypothesized that these instructional tools help

the students in forming a clearer mental

representation as well as in memorizing the

anatomical structures.

2 METHOD

Study 1 (Guillot et al. 2007)

A total of 184 undergraduate students took part in

the experiment. At the beginning of the functional

anatomy learning module, participants completed

spatial ability tests in a quiet room. The Group

Embedded Figures Test (GEFT) was used to

evaluate the degree of field dependence–

independence and the Vandenberg and Kuse Mental

Rotation Test (VMRT) evaluated MR ability. At the

end of the semester all the students completed the

anatomy examination consisting of a multiple choice

225

Hoyek N., Collet C., Guillot A., Thiriet P. and Sylvestre E..

EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH VALIDATION FOR THE USE OF 3D IN TEACHING HUMAN ANATOMY.

DOI: 10.5220/0003337002250227

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2011), pages 225-227

ISBN: 978-989-8425-50-8

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

test made up of 220 propositions within a 60-min

period.

Study 2 (Hoyek et al. 2009)

32 undergraduate students attending functional

anatomy course took part in the experiment. They

were assigned in two groups. In the “MR training

group”, 16 students attended 12 MR training

sessions of 20 min each, three times per week. In the

“Anatomy Control group”, during equivalent time,

16 other students were enrolled in physical activities

that did not have any link with MR ability (e.g.,

gymnastics was proscribed). Before the first

functional anatomy learning session, all participants

completed the VMRT (pre-test). After the training

period all participants completed the VMRT

(posttest). The anatomy examination was finally

scheduled at the end of the learning module. It was

composed of questions that were considered as

requiring either MR or specific knowledge. To

evaluate the effect of the training sessions on MR

ability, the scores on the VMRT was compared in

both groups. Finally, the anatomy scores were taken

into account to investigate the effect of MR training

sessions on anatomy test.

Study 3

180 students enrolled in human anatomy module

were randomly assigned into 3 groups. The 2D

group learned the femur osteology using 2D black

and white images as learning tools. The 3D Video

group watched a 3D animated video of the femur

during learning. Finally the PDF group had an

interactive PDF of a 3D image of the femur as a

learning tool. The hall experience was administered

during a 2 hours practical class. All groups had the

same written support but different visual learning

tools. No explanation was given by the teachers, the

students were asked to learn the femur by

themselves using the common written support and

the defined visual tool of their respective group. At

the beginning of the experience, all participants

completed the VMRT as well as a general anatomy

test in order to make sure that they have the same

MR and anatomy level (pre-test). At the end of the

experience, all participants completed an

examination on the femur (post-test). To evaluate

the effects of each visual tool the femur examination

results were compared among the groups.

3 RESULTS

Study 1 (Guillot et al. 2007)

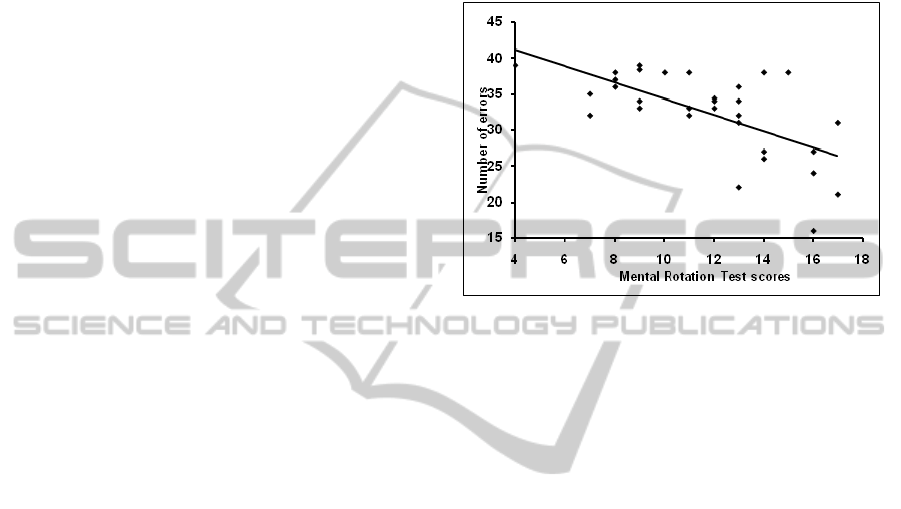

A significant correlation was shown between visuo-

spatial abilities and anatomy examination results for

both the GEFT and the VMRT (fig 1).

Figure 1: Correlation between anatomy examination errors

number and VMRT score. Students having good VMRT

scores made fewer errors on the anatomy examination.

Study 2 (Hoyek et al. 2009)

No significant difference was found between the

three groups, (F2, 45 = .12, p > .05, ns) on the

VMRT pre-test scores hence attesting for their

homogeneity. However the performance

enhancement was greater in the MR training group

compared to the anatomy control group (t = 4.14,

p <.001) suggesting a positive effect of MR training

sessions on VMRT performance. In MR questions,

the MR training group tended to score slightly better

than the anatomy group (F1, 29 = 3.52, p = .07). By

contrast, we did not found any statistical difference

regarding the specific knowledge questions (F1,

29 = .02, p = .8). Anatomy scores results are shown

in figure 2.

CSEDU 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

226

Figure 2: Anatomy examination scores. MR training group

(in red) had better results on the anatomy questions

requiring MR ability (right histogram).

Study 3

Unexpectedly no significant results were found

between the 3 groups on the post-test scores.

Consequently, using 3D visual tools was not

beneficial in this particular experimental design.

4 DISCUSSION

The correlations found in study 1 underscore the

advantage of students with high spatial abilities.

Such abilities could therefore be considered reliable

forecasters of success in acquiring human anatomy

knowledge. Furthermore, such predictive tests could

affect technical skills learning and training in

various scientific (e.g. architecture and design) and

medical disciplines, and help to identify students

who might need supplementary teaching modules.

Study 2 extended these results. Participants became

more accurate in solving the VMRT after practice

explaining a positive transfer of spatial reasoning.

Furthermore, after MR training, participants may

improve their ability to learn anatomical knowledge

by increasing their ability to make the anatomical

structures rotating. These results emphasize the

argument that spatial ability training as well as using

3D technologies may help student in various

scientific and medical disciplines. However the

unexpected results of study 3 are probably due to the

method. We argue that 2 hours are insufficient to

master 3D tools and then to acquire new anatomical

knowledge. In a future study we will evaluate the

effects of using 3D instructional tools over a hall

teaching semester.

REFERENCE

Garg, A. X., Norman, G., Sperotable, L. 2001. How

medical students learn spatial anatomy. Lancet, 357,

pp.363-364.

Guillot, A., Champely, S., Batier, C., Thiriet, P., Collet, C.

2007. Relationship Between Spatial Abilities, Mental

Rotation and Functional Anatomy Learning. Advances

in Health Sciences Education, 12, pp.491-507.

Hegarty, M., Keehner, M. & Cohen, C. 2007. The Role of

Spatial Cognition in Medicine: Applications for

Selecting and Training Professionals. In G. Allen (Ed)

Applied Spatial Cognition. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum,

285-316.

Hoyek, N., Collet, C., Rastello, O., Fargier, P., Thiriet, P.,

Guillot, A. 2009. Enhancement of Mental Rotation

Abilities and its Effect on Anatomy Learning.

Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 21 (3), pp.201-

206.

Keehner, M., Tendick, F., Meng, M. W., et al. 2004.

Spatial ability, experience, and skill in laparoscopic

surgery. American Journal of Surgery, 188, pp.71-75.

Risucci, D. A. 2002. Visual spatial perception and surgical

competence. The American Journal of Surgery, 184,

pp.291–295.

Rochford, K. 1985. Spatial learning disabilities and

underachievement among university anatomy students.

Medical Education, 19 (1), pp.13-26.

Wanzel, K. R., Hamstra, S. J., Caminiti, M. F., et al. 2003.

Visual-spatial ability correlates with efficiency of hand

motion and successful surgical performance. Surgery,

134 (5), pp.750-757.

EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH VALIDATION FOR THE USE OF 3D IN TEACHING HUMAN ANATOMY

227