SUPPORTING THE IDENTFICATION OF TEACHERS’

INTENTION THROUGH INDICATORS

Aina Lekira, Christophe Després and Pierre Jacoboni

Computer Science Laboratory (LIUM), Université du Maine, Avenue Laënnec, Le Mans, France

Keywords: Teaching intention, Teachers’ self-regulation, Indicators, Learners’ activities regulation, Teachers’ activities

instrumentation, Hop3x.

Abstract: In this paper, we deal with the instrumentation of teachers’ activities: the regulation of learners’ activities

and their self-regulation. Indeed, this latter is essential in order to have better learning effects during

learning sessions. Supporting teachers self-regulation implies giving them information about the real impact

of their work, i.e. do the effect of their interventions meet their initial intention. Here, the focus is on the

identification of the latter. To do this, we adopt a declarative approach and rely on indicators. Moreover, to

assess our proposition, Hop3x, a TEL system, was designed and a pilot test was carried out.

1 INTRODUCTION

Our work deals with Technology-Enhanced

Learning (TEL) research field; it aim specifically at

supporting teachers in their activities.

Studying instrumentation issues and more

precisely instrumentation of teachers’ activities

consists most of the time in proposing models and

tools (Martinez et al., 2003) (Kazanidis et al., 2010)

which allow them to regulate learners’ activities.

Research outcomes most often led to tools designs

which offer teachers a visualization of indicators

(ICALTS, 2004) thus giving teachers information

about learners’ progress (Després, 2003),

productions (Lefevre et al., 2009) and elements

about the conditions in which tasks are carried out

(ICALTS, 2004).

In addition to the support of learners’ activities

regulation, ICALTS JEIRP (ICALTS, 2004)

considers that when teachers are involved in these

situations of instrumented tutoring, they need to be

aware of their own actions, activities and process in

order to evaluate them. Thus, giving teachers

information about their self-regulation: (1)

encourages them to have a reflexive approach about

their tutoring practices, choices and teaching

strategies (ICALTS, 2004), (2) allows them to

reconsider their teaching and pedagogical beliefs

(Benbenutty, 2007) and (3) leads them to refine their

practical experiences, improve their skills

(Capa-Aydin et al. 2009) and simply be more

efficient in their work (Zimmerman, 2000).

Supporting teachers’ self-regulation (awareness

and assessment) is essential because the challenge

related to learners’ regulation improvement is made

through the improvement of teachers’ self-regulation

and consequently results in “better learning effects”

(ICALTS, 2004). Such is the basis of our work. It

implies giving teachers information about the effects

of their actions, especially their interventions during

learning sessions.

In order to carry out this support, this paper will

focus on identifying their teaching intentions. The

aim is to know what makes them intervene in order

to give them information about the effects of their

interventions by checking the correspondence

between their original teaching intention and the real

effects of their actions.

Our discussion will proceed as follows: section 2

presents our work background and its general issue.

Section 3 describes Hop3x, the TEL system

designed and used in our work. The pilot test is

described in section 4. Its results are presented in

section 5 and discussed in section 6. Finally, we end

the paper by a conclusion and an outlook.

111

Lekira A., Després C. and Jacoboni P..

SUPPORTING THE IDENTFICATION OF TEACHERS’ INTENTION THROUGH INDICATORS.

DOI: 10.5220/0003343901110116

In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2011), pages 111-116

ISBN: 978-989-8425-50-8

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 BACKGROUND AND

GENERAL ISSUE

2.1 Description of Teachers’ Activities

This subsection presents the processes that teachers

have to manage during learning sessions: the

regulation of learners’ activities and the regulation

of their own tutoring activities (teachers’ self-

regulation) (Fig.1). These processes are deduced

from the adaptation to our work of Bandura and

Zimmerman’s socio-cognitive approach of self-

regulation (Lekira et al., 2009).

The regulation process is preceded by a phase,

which prepares the learning session. This

preparation phase consists in explicitly defining the

observation needs related to teaching objectives and

planning strategies to achieve them. The regulation

process of learners’ activities takes place during the

learning session; it is cyclical with threefold phases

defined as follows:

– a phase of observation in which teachers

monitor and supervise learners’ work.

– a phase of evaluation in which teachers

check if what learners do corresponds to the

objectives of the given activity and tasks.

– a phase of reaction in which teachers

intervene or not, and adopt a remediation

strategy guided by a teaching intention.

Teachers’activities

Observation Evaluation Reaction

Sel

f

‐reaction

Sel

f

‐

observation

Sel

f

‐

evaluation

Remediation

strate

g

ies

Teaching

intention

Learners’

Activities

Regulationoflearners’

activities

Figure 1: Description of teachers’ activities.

The teachers’ threefold self-regulation process is

also cyclical and is defined as follows:

– a phase of self-observation in which teachers

observe the effects of their interventions.

– a phase of self-evaluation in which teachers

check if their interventions have reached the

expected effects and thus meet their initial

teaching intentions.

– a phase of self-reaction in which teachers

validate their interventions or reconsider them

in adopting new remediation strategies.

2.2 Instrumentation of Teachers’

Activities

Our goal is to support teachers in their work by

offering them instruments to better carry out their

tutoring. To do this, we try to give them tools for

each step of the processes they have to manage

during learning sessions.

To reach this goal, we rely on indicators which

are at the core of our work. We here adopt the

ICALTS JEIRP (ICALTS, 2004) definition of an

indicator as a “ variable that describes ’something’

related to the mode, the process or the ’quality’ of

the considered ’cognitive system’ activity; the

features or the quality of the interaction product; the

mode or the quality of the collaboration, when

acting in the frame of a social context, forming via

the technology-based learning environment”. An

indicator has attributes such as name, value, etc.

As seen in Tab.1, in which we suggest the

possibilities of teachers’ instrumentation (a) during

learners’ activities regulation and (b) during their

own self-regulation, we propose to give teachers

indicators about learners’ work during the phase of

evaluation. These indicators are designed thanks to

the activity objectives. In fact, they meet teachers’

needs of synthetic information at a more abstract

level. It enables to quantitatively and qualitatively

determine learners’ work without having to explore

the detailed tracks (Labat, 2002).

Moreover, during

the reaction phase, teachers also rely on the values

of these indicators to intervene.

During the phase of self-observation, the

monitoring tool we want to offer teachers allows

them to visualize and follow the variations of the

values of these indicators. Finally, in the phase of

self-evaluation, they are the witness of the effects of

teachers’ intervention through their positive or

negative evolution.

2.3 The General Issue

Based on our model of learners’ activities regulation

and teachers’ self-regulation, supporting teachers’

self-regulation means measuring the real impact of

teachers’ actions, i.e. following teachers’ reaction

effects through indicators and see if they meet

teachers’ original intentions. In order to give them

feedback about the effects of their interventions and

CSEDU 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

112

Table 1: Teachers’ instrumentation possibilities.

Phase Possibilities of instrumentation

Regulation of learners’ activities

Observation

A monitoring tool enables teachers to supervise

and follow the progress of learners’ activities

(productions, trails, etc.)

Evaluation

A comparison module compares the real values

of indicators to their expected values. This

module supplies teachers with synthetic

information about learners’ activities thanks to

indicators related to activity objectives and

calculated from learners’ tracks.

Reaction

A module obtains and identifies teachers’

intentions (i.e. what makes them react) in order

to support their interventions.

A communication tool allows teachers to

intervene according to the values of indicators

that they considered critical in the evaluation

phase.

Teachers’ self-regulation

Self-observation

A self-monitoring tool provides teachers with a

follow-up tool to keep track of their

interventions (self-monitoring) and the

conditions that surround them.

Self-evaluation

A comparison module provides teachers with

outcomes and gives them information about the

effects of their interventions. They can thus

assess the effects of their actions, performance

and progress in achieving their goals.

Self-reaction

A tool allows teachers to validate one

intervention (by giving them the intervention

performance) or to reconsider it by adjusting

their strategies and adopting a new one to ensure

the achievement of their goals via a

communication tool.

to support their self-evaluation and self-reaction, we

need to know why they react. In other words, we

want to know what makes them intervene, i.e. we

want to identify their teaching intentions.

Getting this teaching intention can be done

automatically or in a declarative way by asking

teachers to declare it. Attempting automatic

identification of teaching intention has an advantage:

its transparency for teachers. But on the other hand

the main disadvantage is the difficulty to detect it

precisely because there are a lot of elements to take

into account such as learners’ profile, their

knowledge and competence level, the type of tasks

or activity in which they are involved, their learning

style, and so on. Thus, this automatic detection leads

to a high error rate in identifying the teaching

intention. Then, the risk of cascading errors is very

high and it is not acceptable in what we want to do

(supporting teachers’ self-regulation) because

identifying teaching intention is the base of the

support of teachers’ self-observation, self-evaluation

and self-reaction.

Thus, we chose to study the declarative way

because teachers’ declarations of their intentions are

likely to have a low error rate: indeed, they identify

their intentions themselves.

As a matter of fact, some issues arise from this

solution: (1) The risk of adding an activity to the

activity, i.e. to increase teachers’ workload. Then,

they may find it too constraining and refuse to give

this information. (2) Teachers may declare teaching

intentions which do not correspond to the content of

their interventions.

In order to study these issues which deal with

getting and identifying teachers’ intention, our

approach consists in relying on indicators. As said

above, they are at the core of our work and we

consider them as the main causes of teachers’

interventions. But we are also aware of the fact that

during learning sessions, other elements come into

play and can affect the decision to intervene. In fact,

teachers can take into account elements such as

learners’ profiles, knowledge and competence level,

the kind of tasks or activity in which they are

involved and so on.

To reach our goal (getting and identifying

teaching intentions), we have designed a tool, which

asks teachers what makes them intervene by

selecting one or a set of indicators in order to allow

the detection of their teaching intentions by the

system. To validate our proposition of detecting

teaching intentions in a declarative way, we made a

pilot test in which we used a TEL system: Hop3x is

described in the next section.

3 HOP3X: THE DESIGNED TEL

SYSTEM

In this paper, we want to infer teaching intentions

from analysis of indicators. To tackle this issue, we

used a TEL system named Hop3x. This TEL system

was designed for learning programming. In our

work, we use it in object-oriented programming.

Hop3x is a track-based TEL system and three

applications compose it:

Hop3x-Student allows learners to edit, compile and

run code and program. It also allows them to

call for help when needed via a communication

tool.

Hop3x-Server collects learners’ interaction tracks

and saves them as Hop3x events. It allows

real-time calculation of indicators.

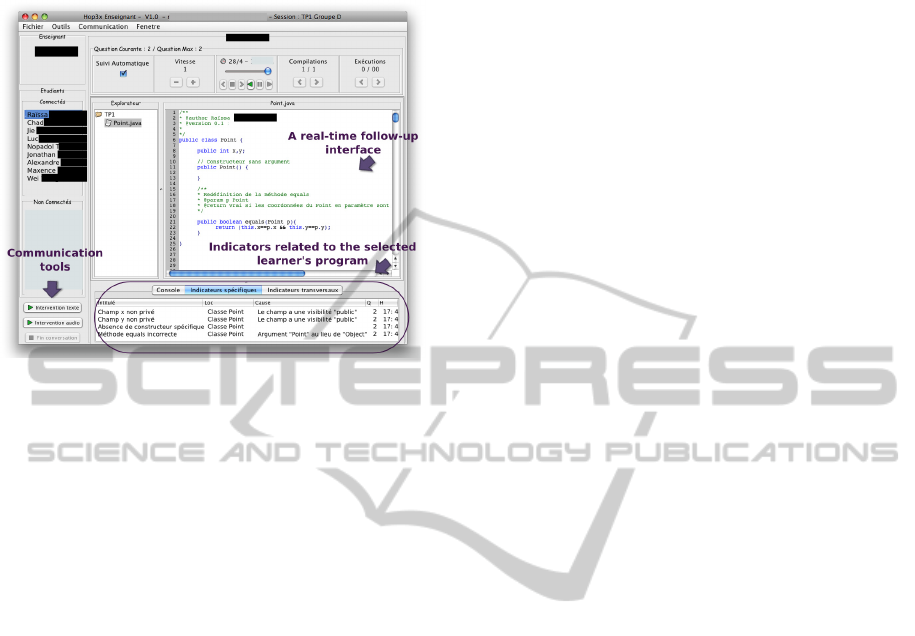

Hop3x-Teacher is a follow-up and intervention tool

for teachers. It allows them to manage a group

of learners in a situation of distance and

real-time lab work (Fig. 2), It also allows them

to follow learners’ activities in real time thanks

to a visualization interface, to have synthetic

information about learners’ productions and

tasks through indicators, to annotate a part of

learners’ program and make them see this

annotation, to intervene via communication

tools, to replay learners’ trails during or after

SUPPORTING THE IDENTFICATION OF TEACHERS' INTENTION THROUGH INDICATORS

113

the session, to visualize the history of their

interventions via a reminder module.

Figure 2: Snapshot of a teacher’s interface using Hop3x.

Learners’ supervision in real time is based on the

architecture of Hop3x. Hop3x architecture based on

client-server model, allows a real-time track of

learners’ interaction as events. An event stored in

Hop3x can be a project creation or removal, a file

creation or removal, a program compilation, a

program run, a text insertion or deletion, etc.

Based on this real time track of learners’

interaction Hop3x performs (a) teachers’ real-time

follow up of learners’ activities, (b) calculation of

indicators and (c) teachers’ visualization of these

indicators related to learners’ tasks progress and

trails.

4 PILOT TEST

The pilot test dealt with an academic French

university context. It was carried out from January

2010 to March 2010 and took place with two

teachers and thirty-six learners split into two groups

of eighteen. Each group was working on three

topics, at the rate of on topic per three-hour lab work

session.

The lab work sessions were part of a course

entitled “Object-oriented programming and Java”.

The learners involved in our pilot test were

undergraduate students. These learners were novices

in Java programming but during the preceding term,

they were introduced to the basics of object-oriented

programming. Before each learning session using

Hop3x in which learners practiced Java

programming, they attended lectures and tutorials

about the notions and concepts that they would

implement during lab work.

During a learning session (lab work), there was

no face-to-face interaction between teachers and

learners. Teachers could, in real time, follow

learners’ tasks and activities i.e. learners’ programs

and java codes and could interact with learners

through communication tools by selecting a set of

indicators (declaring their intentions) and by

choosing the way (talking or sending a message)

they intervene.

Teachers could be proactive or reactive. Indeed,

teachers could intervene, either because learners’

directly solicit (reactive modality) or on they own

initiative owing to indicator values therefore

(proactive modality).

Three tutoring tasks that teachers have to

perform during lab work were identified:

(a) Managing the progress of learners’ activities

depending on the time.

(b) Supporting learners in their knowledge and

skill acquisition

(c) Coaching learners in their acquisition of good

programming practices.

For each tutoring task indicators allow teachers

to make decisions. We identify two kinds of

indicators that reflect both quantitative and

qualitative aspects of learners’ activities: (1) specific

indicators are linked to one topic or subject of lab

work, e.g. there are indicator about the mastery of

the encapsulation concept, (2) transverse indicators

are not linked to one subject of lab work, e.g.

indicators about the use of appropriate programming

style (respect of javaStyle rules), the writing of

comments (especially javaDoc comments).

This pilot test fed our corpus and allowed us to a

large amount of tracks and events. On average, we

obtained 3995 events per learner for three hours of

lab work that is 386 312 events in total, on which

our results – which will be presented in the next

section – are based.

5 EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

One of our issues, when we wanted to identify

teaching intentions in a declarative way was the

possibility that this declarative approach could be

constraining for them and thus they could refuse to

put this information in the system because it could

overload them with an additional task.

To get those results, we analyzed the collected

tracks from the pilot test, especially the

CSEDU 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

114

interventions. For each intervention, we checked if

teachers declare their intentions by selecting

indicators. We dealt with 242 interventions that

teachers made during the experiment (interventions

for all groups and all lab work). Out of these

interventions, 29, i.e. 11%, are reactive i.e.

interventions caused by a learner’s call for help. 213

(about 89%) are proactive. We are interested in

proactive interventions caused by indicator values.

Most of the time, in these proactive

interventions, teachers selected indicators while

intervening: in 175 interventions (82%), teachers

declared their intentions.

Out of the remaining 38 interventions (18%),

half (18) were interventions in which teachers

wanted to select indicators but had not defined them

before the learning session; thus, the system could

not calculate them. In the last portion which includes

18 interventions (9% of all proactive interventions),

teachers forgot to select indicators while intervening,

although the latter were available.

The second issue of our work, when identifying

teachers’ intention was the possible

non-correspondence between what teachers declared

they wanted to do and what they had actually done.

To address this issue, we obtained some figures

from the analysis of 175 interventions, those in

which teachers had selected indicators. To check the

correspondence between the contents of teachers’

interventions and the indicators they selected, we

listened to 93 audio interventions that had been

recorded during the pilot test. We also scrutinized 82

textual interventions extracted from the corpus of

tracks we collected.

Tab. 2 shows the results of the analysis and

presents the relationship between teachers’

intervention contents and the problems pointed out

by the indicators they selected. As we can see, the

contents of teachers’ interventions do not match the

indicators they selected in only 3,6% of cases.

In about 60%, the contents perfectly match the

problems pointed out by the indicators selected by

teachers during their interventions. The remaining

36.6% (i.e. 21 interventions out of 175) corresponds

to a partial correspondence. In this category, in 90%

of cases correspond to situations in which teachers

went further in their interventions than they had

declared: they solved more problems than they had

declared through the choice of indicators. By

contrast, in the remaining 10%, intervening teachers

didn’t deal with all the problems they had declare to

solve.

Table 2: Relationship between teachers’ interventions

contents and the indicators they selected.

Correspondance

No

correspondance

Partial

correspondance

Topic 1 58% 2% 40%

Topic 2 65% 3% 32%

Topic 3 56% 6% 39%

Total 59,66% 3,66% 36,6%

6 DISCUSSION

Getting and identifying teachers’ intentions during

learning sessions is not easy because of the way we

choose to get this information. This identification

can be disrupted or can even fail in two ways. First

the declarative way adds another task for teachers

during learning sessions; it can thus overload them

with work and be constraining for them. Secondly,

what teachers really do in their interventions does

not always match what they declare to do.

Thanks to the pilot test, we could implement our

approach and assess if this way of getting teaching

intention is effective. Results of the pilot test reveals

that most of the time teachers declare correctly their

teaching intentions trough indicators.

In fact, we are interested in proactive

interventions because in reactive ones, teachers react

to learners’ call for help. Indeed, there are no

indicators to select to identify their intentions since

they want to support learners for problems of which

they have no prior knowledge at the time of the

intervention.

In taking into account these proactive

interventions (about 90% of 242 interventions, i.e.

213 interventions), the analysis of the data tracks

from the pilot test and related to our initial issues

shows various elements:

(a) In 82% of their interventions teachers

correctly put the information about their teaching

intention into the system. It seems that this way of

getting teaching intentions is not constraining for

teachers because the percentage in which they did

not give them is very low (18 interventions out of

213, i.e. 9% of proactive interventions).

(b) Among these 82% of cases (i.e. 175

interventions) in which teachers declare their

intentions, the percentage of interventions in which

the selected indicators had no relation with the

interventions contents is very low: it represents only

3.66% of 175 interventions. The number of cases in

which there is a perfect correspondence between the

intervention contents and the problems underlined

by the indicators that teachers selected, is acceptable

SUPPORTING THE IDENTFICATION OF TEACHERS' INTENTION THROUGH INDICATORS

115

because it represents 105 interventions (out of 175,

i.e. about 60%).

The case of partial correspondence represents 64

interventions (out of 175, i.e. 36.6). In 4 of these,

teachers selected too many indicators while

intervening. We noticed while listening to the audio

conversations that these interventions lasted more

than 5 minutes. In analyzing the contents, we also

learned that in these cases teachers dealt with one

problem and interacted with the learner about it but

the latter had difficulty resolving the problem.

Teachers took time to explain, step by step, how to

come to a resolution of the problem. Thus, we can

suppose that in these situations they did not want to

overload the learner in giving him a lot of

information. They tried consequently to help

learners gradually by first resolving the problem

with which they had difficulties, and then took the

remaining ones into account.

In the case of partial correspondence, 60

interventions concern situations where teachers do

more than they had declared. They have done the job

in so far as they have actually interacted with the

learner about the selected problems. Moreover,

doing more than was originally declared poses

problems because the identification of teaching

intention is not complete. Thus, since teaching

intention is at the core of teachers’ self-regulation,

its incomplete identification can bring up some

issues at the time of the instrumentation of the

self-regulation process.

7 CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

In our work, we want to instrument teachers’

activities during learning session. Here, we focus on

identifying teachers’ intentions through a declarative

approach by asking teachers what makes them

intervene. For that, we offer them a tool in which

they can select a set of indicators, which are

supposed to be the triggers of their interventions.

Experimental results show that most of the time (in

82% of interventions) when they intervened teachers

declared their intentions through indicators

selection. However, partial correspondence between

the interventions contents and the problems

underlined by indicators teachers selected while

intervening arise new issues. Indeed, incomplete

identification of teaching intentions could lead to

failure or errors during teachers’ self-regulation

support since this latter is based on teaching

intentions. Addressing these issues will be our

short-term objectives by giving teachers the

opportunity to adjust their intentions after the

interventions (add or deletion of some indicators

from the list of indicators selected pre-intervention).

Our mid-term objectives will be the implementation

of teachers’ self-regulation process and its

evaluation by carrying out a new experimentation.

We also plan for our long-term objectives to propose

learners some of the indicators available for teachers

in order to support self-regulated learning (Butler et

al., 1995).

REFERENCES

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. NJ Prentice

Hall Publishers, Englewood Cliffs.

Benbenutty, H. (2007). Teachers’self-efficacy and

self-regulation. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/.

Butler, D. L., Winne, P. H. (1995). Feedback and self-

regulated learning: A theoretical synthesis. Review of

Educational Research, 65:245-281.

Capa-Aydin, Y., Sungur, S., and Uzuntiryaki, E. (2009).

Teacher self-regulation: Examining a

multidimensional construct. Educational Psychology,

29:345–356.

Després, C. (2003). Synchronous tutoring in distance

learning. In International Conference on Artificial

Intelligence, pages 271–278, Australia.

ICALTS-JEIRP (2004). Interaction and collaboration

analysis’ supporting teachers and students’

self-regulation, delibrables 1, 2 and 3.

http://www.rhodes.aegean.gr/ltee/kaleidoscope-icalts.

Kazanidis, I., Satratzemi, M. (2010). Modeling user

progress and visualizing feedback: the case of ProPer.

In 2

nd

International Conference on Computer

Supported Education. pages 46-53, Spain.

Labat, J.-M. (2002). Quel retour pour le tuteur ? In

Technologies de l’Information et de la Communication

dans les Enseignements et dans l’industrie, France.

Lefevre, M., Cordier, A., Jean-Daubias, A., and Guin,

S.(2009). A teacher-dedicated tool supporting

personalization of activities. In World Conference on

Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and

Telecommunications, pages 1136–1141, Hawaii.

Lekira, A., Després, C., and Jacoboni, P. (2009).

Supporting teacher’s self-regulation process. In 9th

IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning

Technologies, pages 589–590, Latvia.

Martinez, A., Dimitriadis, Y., Gomez, E., Rubia, B., and

De La Fuente, P. (2003). Combining qualitative and

social network analysis for the study of classroom

social interactions. Computers and Education,

41:353-368.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A

social cognitive perspective. Handbook of

self-regulation, pages 13–38.

CSEDU 2011 - 3rd International Conference on Computer Supported Education

116