CONTEXT-AWARE SERVICES FOR GROUPS OF PEOPLE

I

chiro Satoh

National Institute of Informatics, 2-1-2 Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo, 101-8430, Japan

Keywords:

Context-awareness, Ubiquitous computing, Agents.

Abstract:

This paper presents a framework for providing context-aware services in public spaces, e.g., museums. The

framework is unique among other existing context-aware systems in implementing services as mobile agents

and supporting groups of users in addition to single users. It maintains a location model as containment re-

lationships between digital representations, called virtual counterparts, corresponding to people, terminals,

or spaces, according to their locations in the real world. When a visitor moves between exhibits in a mu-

seum, it dynamically deploys his/her service provider agents at the computers close to the exhibits via virtual

counterparts. When two visitors stand in front of an exhibit, service-provider agents are mutually executed

or configured according to the member of the visitors. To demonstrate the utility and effectiveness of the

system, we constructed location/user-aware visitor-guide services and experimented with them for two weeks

in a public museum.

1 INTRODUCTION

Many of the early applications of ubiquitous comput-

ing have focused on interaction between individual

users and their environments. They have paid little

attention to environments that might effectively sense

and respond to groups of co-located people. For ex-

ample, a smart space is one of the most popular topics

in ubiquitous computing research. It is an environ-

ment with sensing devices as well as embedded com-

puters so that it enables individual users to perform

tasks efficiently by offering unprecedented levels of

access to information and assistance from computers

according to the situation of individual users. How-

ever, much of our time is spent in shared physical

spaces, so it is important to consider how an environ-

ment might effectively sense and respond to groups of

co-located people as well as individual people.

When there is only one user in a space, context-

aware services should be customized and provided to

him/her. However, when there are multiple users in

a space, context-aware services should not be cus-

tomized to particular users so that the services can

be shared by them. Furthermore, setting services for

groups of people and devices should be selected and

customized according to the combination of people in

current places in addition to the people themselves.

For example, when a married couple stands in front

of digital signage, advertising content displayed on

the signage should be specific to neither mens’ nor

women’ items. When a visitor stands in front of an

exhibit in a museum, where another visitor is already

standing, annotation services provided from a termi-

nal close to the exhibit may be provided to the exist-

ing visitor, and then the new visitor sequentially, or

customized to the two visitors.

This paper presents a framework for providing

context-aware services to not only individual peo-

ple but also groups of co-located people in specified

spaces. Since such services tend to depend on the co-

location of people, the framework maintains a loca-

tion model for the real world. It introduces the no-

tion of virtual counterparts for people, physical enti-

ties, and terminals, where each counterpart is an pro-

grammable entity. The model is maintained as a struc-

tural organization of virtual counterparts according

to containment relationships between the locations of

their targets, e.g., people, computers, and spaces. This

framework supports location-aware communications

between people and between people and computers,

in the sense virtual counterparts can only communi-

cate with other counterparts when the targets, e.g.,

people and computers, are in the same spaces, e.g.,

rooms or floors. When multiple users are close to

a terminal, their counterparts interact with the termi-

nal’s counterpart to provide services to them. Virtual

counterparts corresponding to terminals are used as a

mechanism for deploying services at the terminals.

54

Satoh I. (2011).

CONTEXT-AWARE SERVICES FOR GROUPS OF PEOPLE.

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Pervasive and Embedded Computing and Communication Systems, pages 54-63

DOI: 10.5220/0003367600540063

Copyright

c

SciTePress

2 RELATED WORK

There have been several agent-based or non-agent-

based attempts to develop context-aware services for

museums with the aim of enabling visitors to view

or listen to information about exhibits at the right

time and in the right place and to help them navigate

between exhibits along recommended routes (Chev-

erst et al., 2000; Fleck et al., 2002; Oppermann and

Specht, 2000). However, most of these existing at-

tempts have been developed to the prototype stage

and tested in laboratory-based or short-time exper-

iments with professional administrators. They also

have been designed in an ad-hoc manner to provide

specific single services in particular spaces, i.e., re-

search laboratories and buildings. For example, real

systems are required to be robust and provide users

with the services that they are designed to provide,

whereas prototype systems for demonstrations are of-

ten allowed to be unreliable and provide insufficient

services. There is a serious gap between laboratory-

level or prototype-level systems and practical sys-

tems. Therefore, this section only discusses several

related studies that have provided real applications to

real users in public spaces, particularly museums.

One of the most typical approaches in public mu-

seums has been to provide visitors with audio anno-

tations from portable audio players. These have re-

quired end-users to carry players and explicitly in-

put numbers attached to the exhibits in front of them

if they wanted to listen to audio annotations about

the exhibits. Many academic projects have pro-

vided portable multimedia terminals or PDAs to vis-

itors. These have enabled visitors to interactively

view and operate annotated information displayed on

the screens of their terminals, e.g., the Electronic

Guidebook, (Fleck et al., 2002), the Museum Project

(Ciavarella and Paterno, 2004), the Hippie system

(Oppermann and Specht, 2000), ImogI (Luyten and

Coninx, 2004), and Rememberer (Fleck et al., 2002).

They have assumed that visitors are carrying portable

terminals, e.g., PDAsand smart phones, and they have

explicitly input the identifiers of their positions or

nearby exhibits by using user interface devices, e.g.,

buttons, mice, or the touch panels of terminals. How-

ever, such operations are difficult for visitors, partic-

ularly children, the elderly, and handicapped people,

and tend to prevent them from viewing the exhibits

to their maximum extent. These approaches suffered

from several serious problems in real museums. One

of the most serious of these associated with portable

smart terminals and multimedia systems is that they

prevent visitors from focusing on the exhibits them-

selves because visitors tend to become interested in

the device rather than the exhibitions themselves.

A few researchers have attempted approaches to

support users by using stationary sensors, actuators,

and computers. However, most of these systems

have stayed at the prototype- or laboratory-level and

have not been operated or evaluated in real muse-

ums. Therefore, the results obtained may not be

able to be applied in practical applications. Of these,

the PEACH project (Rocchi et al., ) has developed

a visitor-guide system for use in museums and its

members have evaluated it in a museum. The sys-

tem supported PDAs in addition to ambient displays

and estimated the locations of visitors by using in-

frared and computer-vision approaches. Although the

project proposed a system for enabling agents to mi-

grate between computers (Kruppa and Kruger, 2005)

by displaying an image of an avatar or character cor-

responding to the agent on remote computers, it could

not migrate agents themselves to computers. Like the

PEACH project, several existing systems have intro-

duced the notion of agent migration, but they sup-

ported only the images of avatars or codes with pieces

of specified information, instead of the agents them-

selves. Therefore, their services could not be defined

within their agents independent of their infrastruc-

tures, so that they could not be used to customize mul-

tiple services while the infrastructures were running,

unlike our system. The PEACH project used an RFID

tag system to identify users (Kuflik et al., 2006), but it

assumed to use portable terminals were used. All the

work discussed previously aimed at providing single

users with services.

We discuss differences between the framework

presented in this paper and our previous frameworks.

We earlier constructed a location model for ubiqui-

tous computing environments (Satoh, 2005; Satoh,

2007). Like the frameworkpresented in this paper, the

model represented spatial relationships between phys-

ical entities (and places) as containment relationships

between their programmable counterpart objects and

deployed counterpart objects at computers according

to the positions of their target objects or places. We

previously presented a context-aware museum guide

system (Satoh, 2008b) and a mobile agent-based sys-

tem for providing services in public museums (Satoh,

2008a). Our previous model and systems provided

no support to location-aware communications and

group-aware communications, unlike the framework

presented in this paper.

3 BASIC APPROACH

This section describes basic ideas behind the frame-

work presented in this paper.

CONTEXT-AWARE SERVICES FOR GROUPS OF PEOPLE

55

3.1 Example Scenario

Suppose a context-aware visitor-guide system is in a

museum. Most visitors to museums lack sufficient

knowledge about exhibits in the museum and they

need supplementalary annotations on these. How-

ever, as their knowledge and experiences are varied,

they may become puzzled (or bored) if the annota-

tions provided to them are beyond (or beneath) their

knowledge or interest. User-aware annotation ser-

vices about exhibits are required. For example, when

a user stands in front of an exhibit, an annotation

service about the exhibit is provided in his/her per-

sonal form on a stationary terminal close to the ex-

hibit. However, there are multiple users in a public

space. Suppose a visitor arrives in front of an exhibit,

where another visitor is standing and receiving an an-

notation service from on a terminal there. We have

several approaches to solving this. 1) After the an-

notation service for the existing visitor has finished,

an annotation service for the new visitor is provided.

2) The annotation service for the existing visitor is

shared by and customized to the existing and new vis-

itors. In fact, we constructed and provided such a

context-aware visitor-guide system to several muse-

ums (Satoh, 2008a; Satoh, 2008b). This problem was

serious during rush hours at the museums.

3.2 Design Principles

To provide services according to groups of co-located

people, we need to model the locations of the

people and the terminals that provide the services.

This framework maintains a symbolic location model

about their locations to select and customize services.

The model is unique to other location models, because

it is maintained as a structural relationship between

programmable entities, called virtual counterpart ob-

jects, corresponding to people, physical entities, and

places in the real world.

Containment Relationship Model. Virtual coun-

terparts are structurally organized based on geograph-

ical containment relationships between their targets,

e.g., people, physical objects and places. Each coun-

terpart is contained by at most one counterpart, called

a parent counterpart, and can contain more than zero

counterparts, called children. For example, each floor

is contained within at most one building and each

room is contained within at most one floor. Each of

the counterparts corresponding to these rooms is con-

tained in the counterpart corresponding to the floor.

The model spatially binds the positions of objects and

places with the locations of their virtual counterparts.

When a physical entity moves to another location in

the physical world, the model deploys its counterpart

at the counterpart of the destinations.

Location-aware Communication. Our framework

uses the spatial co-location of physical entities as a

primary attribute for selecting communication part-

ners. This is because communication between peo-

ple also tends to be done in the same space, i.e., the

same room and nearby fields, rather than those in dif-

ferent rooms or on different floors. Communication

partners, including terminals, should also be selected

according to their co-locations. Co-locations between

people and terminals are modeled as a spatial relation-

ship between the virtual counterparts corresponding

to the people and the terminals. The virtual counter-

parts for terminals can explicitly define the condition

that activate and configure services provided to the

groups of people in addition to their locations. The

framework treats location-aware communications as

interactions between virtual counterparts. The virtual

counterparts corresponding to terminals communicate

with the virtual counterparts corresponding to people.

Support to Groups of People. Each virtual coun-

terpart has two types of communications with other

counterparts, called vertical and horizontal commu-

nications. The first enables each counterpart to com-

municate with its child virtual counterparts and vice

versa and the second enables each counterpart to com-

municate with its sibling containers that are contained

in the same parent counterpart. It also supports mul-

ticast communications. To support communications

between multiple users, each virtual counterpart can

communicate with multiple virtual counterparts via

the former’s parent where the latter virtual counter-

parts are contained in the parent through a multicast-

ing communication manner. For example, when two

persons is in front of digital signage, the counter-

part objects corresponding to them are contained in

the counterpart corresponding to the service-available

scope of the digital signage. The former and latter

counterparts communicate with each other and then

the latter configures and plays the content displayed

on its target digital signage.

Context-aware Services. Computers, including

public terminals, have their own counterparts. The

framework classifies smart objects into two types.

The first can download software for defining ser-

vices from external systems and execute the software.

The second only provide its own initial service and

has built-in communication interfaces to control itself

PECCS 2011 - International Conference on Pervasive and Embedded Computing and Communication Systems

56

from the external systems through networks. A vir-

tual counterpart for a device in the first type is to pro-

vide forward deployable software that the device can

execute. This framework uses mobile agent technol-

ogy to deploy software at terminals. To assist visitors

from stationary terminals in museums, software to de-

fine services needs to continue to provide the services

for them, even when they move from one location to

the next. Services are implemented as mobile agents,

where mobile agents are autonomous programs that

can travel from computer to computer under their own

control. Virtual counterparts corresponding to termi-

nals forward service-providermobile agents to the ter-

minals.

Service-available Spaces. Public terminals have

their own spatial scope where people can see or lis-

ten to content. User-specific services should only be

played when its users are in its scope. Several re-

searchers on virtual-reality (VR) have provided the

notion of virtual scope, often called aura, where in-

teractions between two objects in VR only become

possible when the objects’ scopes collide or overlap

(Carlsson and Hagmnd, 1993; Greenhalgh and Ben-

ford, 1995). Public terminals can be seen by peo-

ple when the former and latter are within a specified

scope. For example, a public terminal has a half-

meter sphere so that a user can directly manipulate

the terminal. User-aware content should only be dis-

played at a terminal when the target user is in front of

the the terminal. The framework introduces the scope

of each terminal as a virtual counterpart. When a user

is within the scope, his/her virtual counterpart is lo-

cated in the virtual counterpart corresponding to the

scope.

3.3 Bridging between Real World and

Virtual World

This section outlines the ideas behind our frame-

work. Each physical entity, e.g., a person, legacy ap-

pliance, or physical place, e.g., a building or room,

has more than one virtual counterpart object. Each

counterpart object is constructed as a programmable

entity. Each virtual counterpart object can be con-

tained within at most one virtual counterpart object

according to the containment relationships in the real

world. It can also be dynamically deployed between

virtual counterpart objects as a whole with all its in-

ner counterpart objects when its target physical entity

moves. The framework maintains a location model

as an acyclic-tree structure of virtual counterpart ob-

jects, like Unix’s file directory. When a virtual coun-

terpart contains other virtual counterparts, we call

the former a parent and the latter children. When

physical entities, places, and computing devices move

from location to location in the physical world, the

framework detects their movements through location-

sensing systems and changes the containment rela-

tionships of the counterparts corresponding to the

moving entities, their sources, and destinations.

Unlike other existing tree-based location mod-

els, virtual counterparts are not only digital repre-

sentations of physical entities or places but also pro-

grammable entities that can communicate with other

counterparts. The framework uses location as its

primary attribute for discovering and selecting ser-

vices. Inter-counterpart communications select po-

tential communication partners according to where

these are located. An entity, including a person, phys-

ical object, or a computing device can specify the

kind of surroundings in which it is willing to interact

with its communication partners, e.g., visual, audio,

or manual manipulation, which will enable it to inter-

act with other devices.

When multiple virtual counterparts corresponding

to members of a group of people are contained in the

virtual counterpart corresponding to the scope of a

service provider device, the latter counterpart com-

municates with the former counterparts. Since the

framework can be maintained on different comput-

ers, it provides programs to virtual counterparts with

syntactic and (partial) semantic transparency for re-

mote interactions by using proxy elements that have

the same interfaces as the remote virtual counterparts

themselves. The underlying location-sensing systems

can dynamically relocate virtual counterparts based

on changes in the locations of their target entities in

the physical world.

4 DESIGN AND

IMPLEMENTATION

Our framework consists of four subsystems: 1)

context-aware directory servers, called CDSs, 2) vir-

tual counterpart management systems, 3) agent run-

time systems, and 4) service provider agents. The

first is responsible for reflecting changes in the real

world and the location of users when services are

deployed at appropriate computers. Our system can

consist of multiple CDSs, which are individually con-

nected to other servers in a peer-to-peer manner. Each

CDS only maintains up-to-date information on par-

tial contextual information instead of on tags in the

whole space. The second manages a structure of vir-

tual counterparts according to up-to-date information

on the state of the real world, such as the locations of

CONTEXT-AWARE SERVICES FOR GROUPS OF PEOPLE

57

people, places, and things.

The third is running on stationary computers,

which are located at specified spots close to exhibits

in a museum and are equipped with user-interface

devices, e.g., display screens and loudspeakers. It

is responsible for executing and migrating service-

provider agents, like existing runtime systems for

mobile agents (Smith, 2010). The fourth is an au-

tonomous entity that defines application-specific ser-

vices for visitors. It is implemented as one or more

mobile agents. Virtual counterparts are used as for-

warders in the sense that they migrate mobile agents

from one terminal to the next. The framework deploys

and executes mobile agents at computers near the po-

sitions of the users instead of at remote servers. As a

result, mobile agent-based content can directly inter-

act with users, where RPC-based approaches, which

other existing approaches are often based on, must

have network latency between computers and remote

servers. Mobile agents can help to conserve these

limited resources, since each agent only needs to be

present at the computer while the computer needs the

content provided by that agent.

4.1 Location-sensing Systems

The framework itself is independent of any location-

sensing system. The management system has inter-

faces for monitoring its underlying location-sensing

systems. Tracking systems can be classified into two

types: proximity and lateration. The first approach

detects the presence of objects within known areas

or close to known points, and the second estimates

the positions of objects from multiple measurements

of the distance between known points. The CDSs

support the two types, but they map geometric in-

formation measured by the latter sensing systems to

specified areas, called spots, where the exhibits and

the computers that play the annotations are located.

This is because most context-aware services in pub-

lic spaces should be provided within specified spaces

rather than at specified geometric points. Each CDS

has its own local database to maintain the locations of

visitors and their agents.

Although our system itself is independent of the

underlying sensing systems, the experiment presented

in this paper supported active RFID tag systems,

where museums have provided individual one or

group visitors with RFID tags. These tags are small

RF transmitters that periodically broadcast beacons,

including the identifiers of the tags, to receivers lo-

cated in exhibition spaces. The receivers locate the

presence or position of the tags. As CDSs gener-

ate sensing-system-independent identifiers from the

identifiers of tags, agent runtime systems and agents

should be independent of the underlying location

sensing systems.

When the underlying sensing system detects the

presence (or absence) of a visitor (or the RFID tag

tied to the visitor) in a spot, i.e., the visitor in the spot,

the CDS attempts to instruct the agent attached to the

visitor to the agent runtime system close to his/her

current location.

• The CDS multicasts a query message that contains

the identity of the visitor (or the identity of the

tag) to the CDS that manages the system attempts

to query the locations of the agent tied to the visi-

tor from its local database.

• If the database does not contain any information

about the identifier of the visitor (or the tag tied to

him/his), it multicasts a query message that con-

tains the identity of the new visitor (or the tag) to

other CDSs through UDP multicasting.

• It then waits for reply messages from other CDSs.

Next, if the CDS knows the location of the agent

tied to the visitor (or the tag), it sends a control

message to the agent runtime system that runs the

agent to instruct the agent to migrate to computers

close to the visitor (or the tag).

For example, when a tag bound to a user who has

his/her agents is close to a computer, the system iden-

tifies the user and deploys his/her agents at computers

close to him/her. The system relies on UDP multicas-

ting, but CDSs can communicate with other CDSs,

which are not in their same domain, through TCP/IP

communication. When CDSs sends control messages

to agent runtime systems, they map the identifier

of each tag into the corresponding sensing-system-

independent identifier. When each agent runtime sys-

tem migrates or receives agents, it sends a message

about the identifier of the agents that it leaves from or

arrives at, to nearby CDSs through UDP multicasting.

4.2 Virtual Counterpart Management

The framework itself is independent of programming

languages, but the current implementation uses Java

(J2SE version 1.5 or later versions) as an implemen-

tation language to define the framework itself and vir-

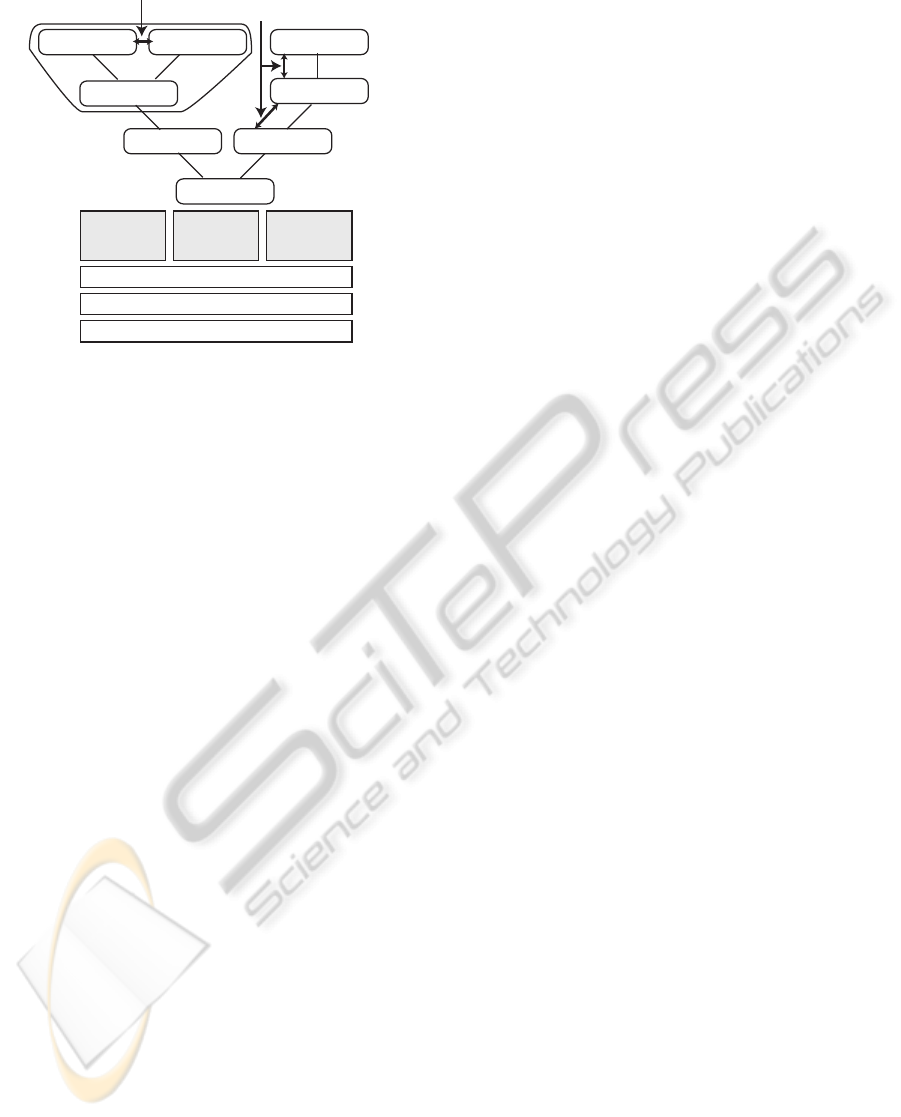

tual counterparts. Figure 1 outlines the basic structure

of a management system for the framework.

Hierarchical Structure

The framework manages a location model as an

acyclic-tree structure of virtual counterparts, where

PECCS 2011 - International Conference on Pervasive and Embedded Computing and Communication Systems

58

OS/Hardware

Transport Protocol

Component

Deployment

Service

Component

Event

Management

Location

Model

Management

Java Virtual Machine

Component G

Component H Component I

Component J

Component K

Component D

Component E Component F

Horizontal communication

Vertical

communication

Figure 1: Virtual counterpart tree.

each virtual counterpart can be defined as a self-

contained computing entity without any description

of a counterpart hierarchy. The management system

provides a container for the counterpart correspond-

ing to a virtual counterpart. The container technol-

ogy developed by Enterprise Java Beans provides in-

terfaces for components and enables them to trans-

parently adapt to runtime services, e.g., it manages

transactions. That is, this framework provides each

agent corresponding to a counterpart with a wrapper,

called a tree container. Each container includes its

target agent, its attributes, and containment relation-

ships between itself and its parent container and be-

tween itself and its child containers. As a result, a

hierarchy of containers is maintained in the form of a

tree structure, which has the component tree nodes of

containers.

Virtual Counterpart

Each virtual counterpart is defined as a mobile agent

and a whole or part hierarchy of counterparts is main-

tained as a acyclic-tree structure of virtual counter-

parts. The framework provides agent runtime sys-

tem(s) on computer(s). The system is responsible

for managing and exchanging virtual counterparts and

controls messages or counterparts with runtime sys-

tems running on different computers (if the frame-

work is maintained in one or more computers). The

runtime system was designed for this framework, but

is similar to other existing Java-based mobile agent

systems.

Each agent can have one or more activities im-

plemented using the Java thread library. The system

can control all the components in its container hierar-

chy, under the protection of Java’s security manager.

Furthermore, the system maintains the life cycle of

the agents: initialization, execution, suspension, and

termination. When the life cycle state of an agent

changes, the system issues certain events to the agent

and its descendent agents.

Counterpart migration within a container hierar-

chy occurs merely as a transformation of the tree

structure of the container hierarchy. When one coun-

terpart is moved to another in the same computer,

a sub-tree, whose root corresponds to its container

and branches, including counterparts, is migrated to

the container that maintains the destination. When a

counterpart can be deployed in another sub-tree main-

tained on another computer, the system marshals the

state of the counterpart, e.g., instance variables and

the counterpart embedded within its container sub-

tree, into a bit-stream and transmits their serialized

state program code through TCP sessions by using the

underlying mobile agent runtime system.

Inter-counterpart Communication

This framework offers several mechanisms to provide

services dependent on the groups of people in addi-

tion to their locations.

• Vertical Communication. All counterparts can

send events to invoke callback methods provided

their children can subscribe to the events that they

are interested in so that they can receive these

events. Each counterpart can be viewed as a ser-

vice provider for its ancestor and child counter-

parts. If ancestor or parent counterparts (or child

counterparts) have service methods that match the

attributes, the system returns a list of suitable ser-

vice methods to the counterparts.

• Horizontal Communication. Each counterpart

can invoke service methods provided by its neigh-

boring counterparts, which are contained in its

parent. When a container sends its parent the at-

tribute that specifies its requirements, the runtime

system searches for suitable services in its neigh-

boring containers. The container can invoke the

services.

Our framework supports three types of inter-

counterpartcommunicationprimitives for vertical and

horizontal communications, which can be located at

the same or different computers, 1) remote method in-

vocation, 2) publish/subscribe-based event passing,

and 3) stream communication. This first supports

vertical and horizontal communications and offers

APIs for invoking the methods of other counterparts

on local or different computers with copies of argu-

ments. Our programming interface for method invo-

cation is similar to CORBA’s dynamic invocation in-

CONTEXT-AWARE SERVICES FOR GROUPS OF PEOPLE

59

terface and does not have to statically define any stub

or skeleton interfaces through a precompiler approach

because ubiquitous computing environments are dy-

namic. The second supports vertical and horizontal

communications. It is useful and efficient for captur-

ing changes in the physical world because they pro-

vide subscribers with the ability to express their inter-

est in an event so that they can be notified afterward of

any event mentioned by a publisher. This framework

provides a generic remote publish/subscribe approach

using Java’s dynamic proxy mechanism, which is a

new feature of the Java 2 Platform.

1

The third sup-

ports horizontal communications. The notion of a

stream is highly abstracted representing a connec-

tion to a communication channel. When partners are

different computers, the model enables two counter-

parts on different hosts to establish a reliable channel

through a TCP connection managed by the hosts.

2

Support to Groups of People

Services should be selected and configured according

to a combination of users within the available scope

of the services in addition to the requirements of the

services themselves. The selection is defined in the

counterpartcorrespondingto the space and the config-

uration is defined in its selected service itself. When a

user enters a place, his/her counterpart is deployed at

the counterpart corresponding to the place. The for-

mer counterpart sends a query message to the latter

counterpart to ask about available services with the

attributes that specify its service requirements. There

are several patterns to execute services when multiple

people are in the place. The current implementation

supports the four navigation patterns as follows:

• The FIFO pattern executes a service for newly

visiting users after executing services for existing

users.

• The Interruption pattern interrupts running ser-

vices for existing users and executes a service for

newly visiting users. After the latter finishes, it

resumes the former.

• The Parallelism pattern executes a service for

newly visiting users, even while running services

for existing users.

• The Synchronization pattern blocks executing ser-

vices when specified conditions are satisfied even

when some users have arrived.

1

Since the dynamic creation mechanism is beyond our

present scope, we have left it for a future paper

2

Since our channel relies on TCP, it can guarantee

exactly-once communication semantics across the migra-

tion of counterparts.

These were implemented as built-in modules for

virtual counterparts corresponding to spaces. The first

was implemented as a queuing mechanism for ex-

clusively executing agents for multiple simultaneous

users. The second and third were to enables the coun-

terpart that the pattern was built on to control its ser-

vices. The fourth was a barrier synchronization in the

sense that it instructed services to be executed after

its specified conditions were satisfied. For example,

services are executed, when two visitors are present

at the same space in the same time. That is, when two

users enter the same spot, the CDS sends two noti-

fication messages to the agent runtime system in the

space in the order in which they entered.

4.3 Agent Runtime System

Each agent runtime system is responsible for execut-

ing and migrating agents to other agent runtime sys-

tems running on different computers through a TCP

channel using mobile-agent technology. It is built

on the Java virtual machine (Java VM) version 1.5

or later versions, which conceals differences between

the platform architectures of the source and destina-

tion computers. It provides each agent with one or

more active threads but it governs all the agents in-

side it and maintains the life-cycle state of each agent.

When the life-cycle state of an agent changes, e.g.,

when it is created, terminates, or migrates to another

runtime system, its current runtime system issues spe-

cific events to the agent to execute specified callback

methods defined in the agent.

Agent runtime systems can exchange agents with

other runtime systems through TCP/IP. When an

agent runtime system migrates an agent to another

runtime system over the network, not only the code

of the agent but also its state is transformed into a

bitstream by using Java’s object serialization package

and then the bit stream is transferred to the destina-

tion.

Since the package does not support the capturing

of stack frames of threads, when an agent migrates

to another computer, the agent needs to stop its ac-

tive threads. Its runtime system propagates certain

events to invoke specified callback methods defined

in the agents so that they can stop their active threads

and release their previously acquired resources. The

agent runtime system on the receiving side receives

and unmarshals the bit stream. Since arriving agents

may explicitly have to acquire various resources, e.g.,

video and sound, or release previously acquired re-

sources, the runtime systems propagate certain events

to agents in order to invoke callback methods defined

in the agents. As agent runtime systems can explicitly

PECCS 2011 - International Conference on Pervasive and Embedded Computing and Communication Systems

60

store agents on secondary storage, so that the agents

can continue to assist their users when the users want

the services provided by the agents.

4.4 Service-provider Agent

Virtual counterparts corresponding to terminals de-

ploy service-provider agents at the terminals. Each

agent is automatically deployed at and maintains per-

user preferenceson a user and record his/her behavior,

e.g., exhibits that they have looked at. The agent can

also define user-personalized services adapted to the

user and access location-dependent services provided

at its current computer. Each agent is spatially bound

to, at most, one user. When a user gets closer to an

exhibit, our system detects his/her migration by using

location-sensing systems and then instructs the user’s

agents to migrate to a computer close to the exhibit.

Mobile agents help to conserve limited resources, be-

cause each agent only needs to be present at the com-

puter for the duration the computer needs the services

provided by that agent.

5 EXPERIENCE

We constructed and carried out an experiment at the

Museum of Nature and Human Activities in Hyogo,

Japan, using the proposed system. Figure 2 is a sketch

that maps the spots located in the museum.

Spot 1

Spot 2

Spot 3

Spot 4

Spot 2

Spot 1

Figure 2: Experiment in Museum.

The experimental environment provided four

spots in front of exhibits, which were specimens

of stuffed animals, i.e., a bear, deer, racoon dog,

and wild boar in an exhibition room of the mu-

seum.

3

Each spot could provide five different pieces

of animation-based annotative content about the an-

imals, e.g., their ethology, footprints, feeding, habi-

tats, and features, and had a display and Spider’s ac-

tive RFID reader with a coverage range that almost

corresponded to the space, as shown in Fig. 3.

3

The number of spots and their locations depend on the

target environments, e.g., museums.

Pendant

(with RFID tag)

Ambient

Display

RFID

reader

Figure 3: Spot at Museum of Nature and Human Activities

in Hyogo.

The experimental system provides each visitor

or group of visitors with colored pendants including

RFID tags. Fig. 4 is an animation of an agent, which

is a virtual owl. The agent is spatially attached to a

pendant assigned to each visitor.

These pendants are colored, e.g., green, orange,

or blue. A newly created agent is provided with its

own color corresponding to the color of the pendant

attached to the agent. For example, suppose that a

visitor enters a spot with the specimen of a racoon

dog and a terminal is located in the spot. His/her vir-

tual counterpart is migrated to the counterpart corre-

sponding to the spot. It communicates with the virtual

counterpart corresponding to the terminal so that an

annotation service about the specimen is played from

the terminal. When another visitor enters the spot,

his virtual counterpart is migrated to the counterpart

corresponding to the spot. It requests the counter-

part corresponding to the terminal to execute annota-

tion services about the specimen in the personal form

of the newly arrived visitors. The experiment sup-

ported the FIFO pattern and an application-specific

pattern. When a newly visiting counterpart requested

the counterpart corresponding to the terminal to play

an annotation to its target user, the latter shorted the

opening and closing parts of the current animation.

The experimental system consisted of one CDS

and runtime systems running on four computers. It

provided GUI-based monitoring and configuration for

agents. When the CDS detected the presence of a tag

bound to a visitor at a spot, it instructed the agent

bound to the user to migrate to a computer contained

in the spot. After arriving at the computer, the run-

time system invoked a specified callback method de-

fined in the annotative part of the agent. The method

first played the opening animation for the color of

the agent and then called a content-selection func-

tion with his/her route, the name of the current spot,

and the number of times that he/she had visited the

spot. The latency of migrating an agent and starting

CONTEXT-AWARE SERVICES FOR GROUPS OF PEOPLE

61

time

time

time

Opening animation

C

losing animation

Annotation about racoon dog

Figure 4: Opening animation, annotation animation, and

closing animation for orange pendant

its opening animation at the destination after visitors

had arrivedat a spot was within 2 seconds, so that vis-

itors could view the opening animation soon after they

began standing in front of the exhibits. By using the

FIFO pattern, annotation services could be mutually

executed in each of the spots.

We did the experiment over two weeks. Each day,

more than 60 individuals or groups took part. Most

of the participants were groups of families or friends

aged from 7 to 16. Most visitors answered question-

naires about their answers to the quizzes and their

feedback on the system in addition to their gender and

age. Although the aim of this paper was not at user

evaluation, we administrated some basic user evalua-

tions. Almost all the participants (more than 95 per-

cent) provided positive feedback on the system. We

could adjust the play time of animations so that the

rate of positive feedback was almost the same inde-

pendently of the crowds of visitors.

The framework only maintained per-user profile

information within those agents that were bound to

the user. It promoted the movement of such agents

to appropriate hosts near the user in response to the

his/her movements. Thus, the agents did not leak pro-

file information on their users to other parties and they

could interact with their mobile users in personalized

form that had been adapted to respective, individual

users. The runtime system could encrypt agents to

be encrypted before migrating them over a network

and then decrypt them after they had arrived at their

destination. Moreover, since each mobile agent was

just a programmable entity, it could explicitly encrypt

its particular fields and migrate itself with these fields

and its own cryptographic procedure. The Java vir-

tual machine could explicitly restrict agents to only

access specified resources to protect hosts from mali-

cious agents. Although the current implementation

could not protect agents from malicious hosts, the

runtime system supported some authentication mech-

anisms for agent migration so that each agent host

could only send agents to and only receive them from

trusted hosts.

6 CONCLUSIONS

We designed and implemented a framework for pro-

viding context-aware services in public spaces, e.g.,

museums. It supported groups of users in addition

to single users and implemented application-specific

services as mobile agents to deploy the services at ter-

minals. It maintained a location model as contain-

ment relationships between digital representations,

called virtual counterparts, corresponding to people,

terminals, or spaces, according to their locations in

the real world. When a visitor moved between ex-

hibits in a museum, it dynamically deployed his/her

service provider agents at computers close to the ex-

hibits via virtual counterparts. When two visitors

stood in front of an exhibit, service-provider agents

were mutually executed or configured according to

the member of visitors. To demonstrate the util-

ity and effectiveness of the system, we constructed

location/user-aware visitor-guide services and experi-

mented with them for two weeks in a public museum.

REFERENCES

Carlsson, C. and Hagmnd, O. (1993). Dive: A platform

for multi-user virtual environments. Computer and

Graphics, 17(6):663–669.

Cheverst, K., Davis, N., Mitchell, K., and Friday, A. (2000).

Experiences of developing and deploying a context-

aware tourist guide: The guide project. In Proceedings

of Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking

(MOBICOM’2000). ACM Press.

Ciavarella, C. and Paterno, F. (2004). The design of a hand-

held, location-aware guide for indoor environments.

Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 8(2):82–91.

Fleck, M., Frid, M., Kindberg, T., Rajani, R.,

O’BrienStrain, E., and Spasojevic, M. (2002).

From informing to remembering: Deploying a

ubiquitous system in an interactive science museum.

IEEE Pervasive Computing, 1(2):13–21.

Greenhalgh, C. and Benford, S. (1995). Massive: A col-

laborative virtual environment for teleconferencing.

ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction,

3(3).

PECCS 2011 - International Conference on Pervasive and Embedded Computing and Communication Systems

62

Kruppa, M. and Kruger, A. (2005). Performing physical

object references with migrating virtual characters. In

Proceedings of Intelligent Technologies for Interactive

Entertainment, pages 64–73. Springer.

Kuflik, T., Albertini, A., Busetta, P., Rocchi, C., O.Stock,

and Zancanaro, M. (2006). An agent-based architec-

ture for museum visitors’ guide systems. In Proceed-

ings of Information and Communication Technologies

in Tourism 2006, pages 57–60.

Luyten, K. and Coninx, K. (2004). Imogi: Take control over

a context-aware electronic mobile guide for museums.

In Workshop on HCI in Mobile Guides.

Oppermann, R. and Specht, M. (2000). A context-

sensitive nomadic exhibition guide. In Proceedings

Symposium on Handheld and Ubiquitous Computing

(HUC’2000), volume LNCS vol.1927, pages 127–

142. Springer.

Rocchi, C., Stock, O., Zancanaro, M., Kruppa, M., and

Kruger, A. The museum visit: Generating seamless

personalized presentations on multiple devices. In

Proceedings of 9th international conference on Intel-

ligent User Interface, pages 316–318.

Satoh, I. (2005). A location model for pervasive comput-

ing environments. In Proceedings of IEEE 3rd In-

ternational Conference on Pervasive Computing and

Communications (PerCom’05), pages 215–224. IEEE

Computer Society.

Satoh, I. (2007). A location model for smart environment.

Pervasive and Mobile Computing, 3(2):158–179.

Satoh, I. (2008a). Context-aware agents to guide visitors in

museums. In Proceedings of 8th International Con-

ference on Intelligent Virtual Agents (IVA’08), volume

LNCS vol.5028, pages 441–455. Springer.

Satoh, I. (2008b). Experience of context-aware services in

museums. In Proceedings of International Confer-

ence on Pervasive Services (ICPS’2008), pages 81–

90. ACM Press.

Smith, I. (2010). Mobile agents. In Handbook of Ambient

Intelligence and Smart Environments, pages 771–791.

Springer.

CONTEXT-AWARE SERVICES FOR GROUPS OF PEOPLE

63