CITIZEN CONTROLLED EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION

IN E-GOVERNMENT

Helder Gomes

ESTGA / IEETA, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

André Zúquete

DETI / IEETA, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Gonçalo Paiva Dias

ESTGA / GOVCOPP, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

Keywords: e-Government, Privacy, Interoperability.

Abstract: The online provision of public services to citizens, e-government, is here to stay. Its advantages are huge,

both for the government and for the citizens. Life-event service is a sound concept in which services are

designed to cater with citizen real needs instead of government departments needs. But this type of services

requires interoperability between government departments. Among other things, interoperability implies the

exchange of information between government departments which traditionally has been implemented by

direct communication. This direct communication raises privacy concerns on citizens since their personal

information is potentially exchanged without their knowledge and control. In this paper we propose an e-

government model where the citizen controls the exchange of his personal information between government

departments.

1 INTRODUCTION

One of the key aspects of e-government is the use of

Information and Communication Technologies

(ICT) for the provision of public services to the

citizens. However, e-government is not only about

the use of ICT but also about the reorganization of

Public Administration (PA) in order to increase

efficiency and provide better services to its users

(citizens and companies), such as life-event services

and one-stop e-government (Organization for

Economic Co-operation and Development 2003;

European Commission 2003).

The provision of life-event services requires

integration of the traditionally fragmented PA

(Klischewski 2004) as well as other private

companies (e.g. banks, insurances, etc.). For

example, the Buying a House life event service

requires the involvement of several PA departments

and private companies (organizations), which have

to interoperate in order to deliver the service. As a

consequence of interoperability, citizen information

previously fragmented across, and confined to,

isolated PA departments is now potentially

accessible to all PA, which raises privacy concerns.

Privacy is a critical issue and is pointed as one

reason for citizen lack of trust in government, which

is one of the barriers to the engagement of citizens in

e-government programs (Eynon 2007).

Given the citizen’s traditional lack of trust in PA

and the amount of information PA departments

collect, some of it with mandatory and confidential

nature, e-government services must be exemplary in

the protection of citizen’s privacy (Lau 2003).

Therefore, interoperability and service delivery

models that foster citizen’s trust and respect citizen’s

privacy are needed. We propose an e-government

interoperability model that places the citizen in

control of the exchange of his personal information

between organizations, namely government

departments or other private companies.

494

Gomes H., Zúquete A. and Paiva Dias G..

CITIZEN CONTROLLED EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION IN E-GOVERNMENT .

DOI: 10.5220/0003402804940499

In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST-2011), pages 494-499

ISBN: 978-989-8425-51-5

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Next, in Section 2, we present a short

characterization of e-government interoperability,

followed by the presentation of our model in Section

3. In Section 4 we discuss the model and in Section

5 we present related work and conclude.

2 E-GOVERNMENT

One characteristic of Public Administration is its

functional fragmentation in multiple independent

departments, such as Taxes, Social Security, etc.

Traditionally, each of these departments acts as an

isolated and independent silo with its own

competences, responsibilities, organization and

information. Services are provided and designed

based in their competences and they have no need to

communicate with each other, since citizens have

the responsibility to obtain (from other

organizations) and provide the documents required

for the service he wants.

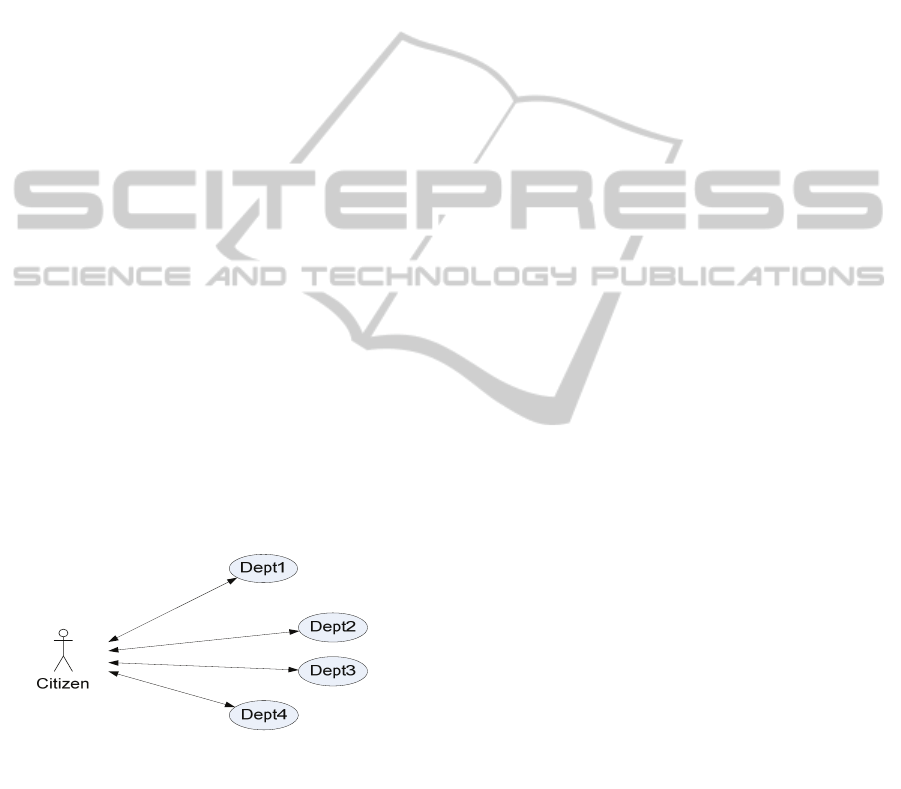

This model, depicted in

Figure 1, has several

problems such as: (i) inconvenience – to obtain a

service from department Dept1 citizen is required to

go first to other organizations (Dept2, Dept3 and

Dept4) to obtain the required documents; (ii)

complexity – citizen must be aware of PA

complexity, i.e., which department(s) provide the

service(s) he needs; (iii) privacy – documents

produced by departments have a standard, uniform

format targeted for multiple uses, usually with more

information than the required for many of those

uses.

Figure 1: Traditional model for provision of services by

the Public Administration.

The traditional paradigm above described is

being improved and replaced by the introduction of

ICT in the PA, in the context of e-government

initiatives. E-government addresses not only the use

of ICT but also the reorganization of PA in order to

provide better services to its users (European

Commission 2003). Two important service delivery

concepts arose: one-stop government and live-event

services.

With one-stop government, services are provided

in a single point of contact and targeted to the

intended public (Kubicek & Hagen 2000). PA

departments provide their services in a conveniently

located single place, thus avoiding the

inconvenience and waste of time for citizens to go

from organization to organization, which may be far

from each other. One-stop shops are examples of

provision of public services based in this concept.

With one-stop e-government, TIC is used as a

platform for the delivery of online one-stop services

to the users (Dias & Rafael 2007).

Life-event services are services targeted to

satisfy citizen’s daily needs (Vintar et al. 2002). Due

to the functional fragmentation of PA, services

needed by citizens to handle common events in

every one’s life (as buying a car, the born of a child,

etc.) typically span across several services from

several PA departments. A life-event service should

integrate in a single entry point all the partial

services provided by the different departments that

together fulfil the citizen real-life need. PA

departments should adapt and integrate in order to

convert a set of partial services and processes into a

single service and the correspondent back-office

process. One big advantage of this approach is that

citizens don’t need to get acquainted with PA

complexity (Dias & Rafael 2007).

The provision of life-event services demands for

interoperability between PA departments.

Interoperability is commonly analysed at three

levels: technical, semantic and organizational.

Technical level deals with the technology necessary

for the systems at organizations to communicate

with each other. Semantic level deals with a

common understanding of government concepts.

The integration of departments to provide citizen-

centric services is handled at the organizational

level. Interoperability at this third level is the most

difficult to achieve, since it implies reorganizations

that interfere with power and responsibility

relationships between people and institutions

(Kubicek & Cimander 2009).

At the higher level of e-government maturity

models (United Nations & American Society for

Public Administration 2002; Layne & Lee 2001)

PA provides citizen-centric services supported by

PA departments fully integrated and transparent to

citizens. This brings huge advantages both for the

government and for the citizen. Advantages for the

government are, for example, efficiency gains

caused by lower redundancy and simpler processes.

Citizens’ advantages are better and more convenient

services. However, all this integration brings more

CITIZEN CONTROLLED EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION IN E-GOVERNMENT

495

vulnerabilities and hence a threat to citizen privacy

(Brooks & Agyekum-Ofosu 2010).

It has been reported that many e-government

initiatives fail (Heeks 2003). The citizens’ lack of

trust in e-government systems is one of the causes

for this failure (Eynon 2007). This lack of trust

comes, for example, from fears of privacy violation,

and also from a generic lack of trust regarding the

governments (Dutton et al. 2005). Ironically, much

of these fears were enhanced by the integration of

government departments, as the previously existent

fragmentation and isolation of PA provide the

citizen some degree of privacy (Bannister 2005).

This is an important issue given the mandatory

nature of much information that the citizen provides

to the state.

One measure against the lack of trust is to allow

the citizen to control his information, namely to

verify its accuracy and correctness, and to control

and verify who accesses it and for what purposes

(Eynon 2007). The model we propose in next

Section is in line with this approach by placing the

citizen in control of the exchange of his information.

3 PROPOSAL

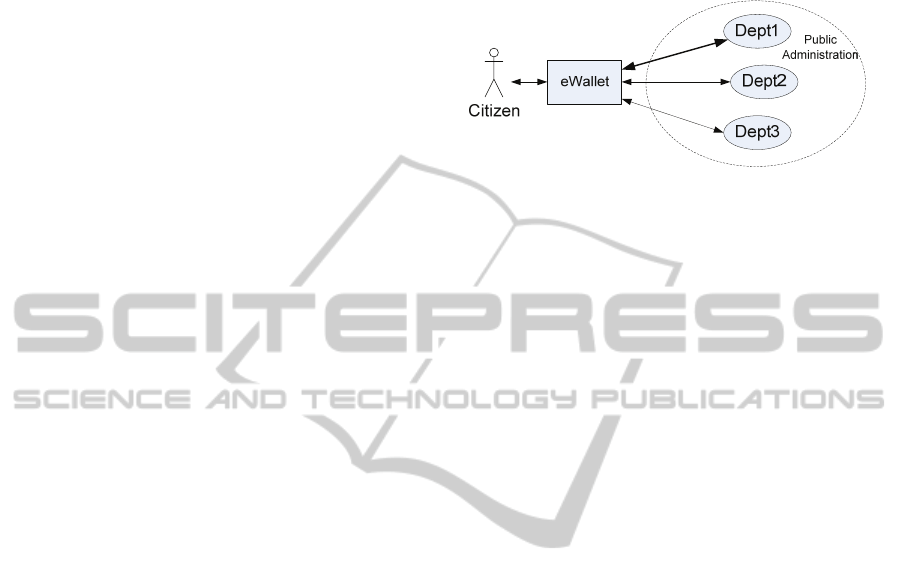

In our model, the citizen is placed between

organizations (PA departments and companies),

controlling the exchange of his information. To

obtain a service from an organization he gathers the

required information, from other organizations, and

decides about its delivery: he controls which

information flows from an organization to another.

Organizations act as providers and consumers of

citizen information that is obtained from, and

delivered to, the citizen. Organizations no longer

need to directly communicate with each other. To

effectively control his information the citizen must

have a novel and appropriate tool, a digital e-

government wallet (egWallet), an application that

assists him in storing, managing, receiving and

delivering his personal information.

Life-event services can be modeled as a set of

partial services, that executed in an appropriated

workflow satisfy a citizen real-life need. The

workflow has inputs (information provided by the

citizen and participating organizations) and produces

outputs, at least for the citizen. Depending on the

citizen specific context, for a given life-oriented

service, multiple workflows can exist, possibly

involving different services and different input and

output information. The selection of the specific

workflow instance and the management of

interactions with participating organizations, for

delivery and retrieve of information, are made by the

egWallet according to citizen privacy definitions.

Figure 2 illustrates this model.

Figure 2: Service provision model with exchange of

information controlled by citizen.

Before start describing the model, a first

presentation of concepts is needed. The concepts are

based in the Information Card Ecosystem (Burton

2009) but are extended beyond identification or

authentication.

Organizations provide and consume citizen

attributes. An attribute is any item of information

that belongs to the citizen. It can be anything from

personal attributes as name, age and other, to objects

like documents, pictures, movies, etc. Attributes are

stored, managed and presented to the citizen, within

the egWallet. Attributes are aggregated in egDocs

(e-government Document), and egDocs are what a

citizen delivers and receives from the services he

requests. An egDoc can be issued by an organization

(Attribute Provider) and can be created and issued

by the citizen himself using attributes he owns and

possibly other egDocs he carries in his egWallet. An

egDoc binds its issuer to the attributes it contains.

There are three types of egDocs: Personal, Managed

and Provided. Personal egDocs are those created by

the Citizen with attributes he owns, e.g., any object

he produces or any statement he produces. Provided

egDocs contain long-lived attributes managed by

another entity, Attribute Provider, and might be

addressed to an identified entity or set of entities,

which should be the only ones able to use it. An

example of a Provided egDoc is a receipt received as

a result of a service. Managed egDocs contain

metadata describing how to obtain short-lived

attributes from its Attribute Provider. These short-

lived attributes must be obtained before each and

every use. An example of a Managed egDoc is the

credit card information to be presented to pay for a

service.

Organizations provide services to citizens. When

providing services, they always act both as Attribute

Providers and Attribute Consumers. They act as

Attribute Consumer since every service requires

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

496

some sort of information (attributes) from the citizen

to be executed (e.g. citizen identification-mail).

These attributes are provided by the citizen, in the

form of egDocs that might be obtained requesting

services from other organizations. They act as

Attribute Provider since every service results in the

production of some set of attributes, encapsulated in

an egDoc, such as a receipt, a certificate, etc.

Let’s consider that citizen wants a service from

Dept1. The service may be a life-oriented service,

and the citizen may get to this point coming from

some life-oriented portal. When the citizen contacts

the service, he gets a “roadmap” for the service that

describes (i) the service required attributes, (ii)

Attribute Providers where they can be obtained, (iii)

the attribute gathering sequence, (iv) the resulting

outputs, and (v) the organization policies that are

applied on the information provided by the citizen.

This “roadmap” is processed by the egWallet to be

adapted to the specific citizen context. For example,

imagine the egWallet contains the citizen marital

status attribute. When accessing some service, if

egWallet receive a “roadmap” requesting some

attributes based on the citizen marital status, it

cleans from the “roadmap” all that do not apply and

presents to the citizen only the required attributes

that effectively apply to his context. All required

attributes are presented in the egWallet together with

the associated information, as possible Attribute

Providers, policies, etc. Some of the required

attributes may already be stored in egWallet while

others may not. According to citizen preferences, the

egWallet can start obtaining the missing attributes,

or wait for the citizen decision. When all attributes

are gathered, the citizen may decide to request the

service and the egWallet delivers all the required

attributes to the service and, at its conclusion,

receives the produced egDocs. Since the service may

take some time to be concluded, the egWallet can be

configured to automatically check for its conclusion.

To assist the citizen in the analysis of his interaction

with government, egWallet registers all transactions.

A concrete scenario might be the application of a

university student for a scholarship. To do this, in

Portugal, students are required to present a family

tax declaration to prove the number of family

members and the family incomes, and a proof that

he has no debts to Social Security. These required

documents clearly provide more information than

the strictly needed for the scholarship application

(e.g., the amount spent in medical care, in the tax

declaration), thus violating the basic need-to-know

principle. High Education Ministry systems are now

connected to Tax Ministry and Social Security

Ministry systems and students are no longer required

to present those documents as the conveyed

information is directly obtained from the proper

sources. However, privacy issues still exist: students

have no guarantee that only strictly need information

is exchanged.

On the contrary, in the model we propose, a

student has full control over which information is

exchanged between organizations since it is

provided by him. When a student accesses the

service to apply for the scholarship, he receives a

“roadmap” listing all the required attributes (the

number of family elements and family income from

the Tax Ministry and a no debts statement from

Social Security Ministry, among others). The student

can clearly verify that only strictly needed

information is required. He instructs egWallet to

obtain those attributes, by accessing the

correspondent services and possibly providing other

attributes. After gathering all required attributes he

instructs egWallet to request the service to apply for

the scholarship, provide the required attributes and

receive an egDoc with the application receipt.

Depending on the student’s preferences much of

these egWallet actions may be automated.

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Privacy

The model we propose has the advantage of making

the citizen aware of the information flows on which

his information is involved. By having the egWallet

registering which information is disclosed, for which

service and when, a citizen has the control over

which information each organization knows about

him. Also he is able to check if services only require

strictly needed information and if it is not the case,

for non mandatory services, he cans always give-up.

It should be noted that after information is

provided, citizen looses the control over it. For this

reason, the citizen must be aware of the conditions

under which he provides his information.

Organizations should provide privacy and security

policies stating their practices and their liability in

case of compliance failures. In the same way, a

citizen defines, in egWallet, the conditions (policy)

under which he agrees to provide his information.

The egWallet compares citizen policies with

department policies and warns the citizen when they

don’t fit. Nevertheless, the citizen always has the

final decision about providing his data.

Citizen awareness regarding the conditions on

CITIZEN CONTROLLED EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION IN E-GOVERNMENT

497

which citizen information is provided is not possible

when organizations directly exchange information.

This awareness makes the citizen able to take

informed attitudes on this subject by doing

suggestions or by complaining to the competent

authorities, for example.

Finally, the issue of trust in government practices

still remains: will government use the data strictly

for the stated purposes? But, this is a political and

cultural issue, not a technology problem.

4.2 PA Reorganization

Together with the use of ICT, reorganization of PA

is a common characteristic of e-government

definitions. At the upper level of e-government

maturity models, PA is fully integrated and services

are life-oriented and based in simple and efficient

inter-organizational processes. This level of

reorganization is not easy to implement as it

involves many political and hierarchical issues.

On the other side, the improvement on service

provision convenience might not be the single

motivation for full integration of PA systems.

Gathering of intelligence information is also a

motivation, especially after 11 September 2001,

(Yildiz 2007) and this raises huge privacy concerns.

So, the full integration of PA is not a consensual

feature. Fragmentation and independence of PA also

has its advantages. The model we propose do not

requires that level of integration of PA and still

allows for the provision of life-oriented services

with citizen controlled exchange of information

between independent organizations.

The level of reorganization implied in our model

is not as deep as full PA integration. However,

reorganization of internal processes and definition of

common PA information models, among others, are

examples of reorganization aspects still needed.

4.3 Information Model

The provision of inter-organizational services

demands for common information models. This

applies both for the full integration of PA and for the

model we propose. The difference in our model is

that information models applicable to the citizen

information must be public and available to

egWallet, so it can handle service interactions and

manage citizen information. Also, those models

should be defined in a computer understandable

form, e.g., by ontologies. This also improves

egWallet versatility to cope with changes in

information models.

An import aspect to address is that of document

formats. PA departments typically provide

information based in standard documents which

contain a standard set of information items

(attributes). To implement the minimal information

disclosure principle, it is important to break those

document formats and have services requiring only

the specific information items really in need and

departments providing services that delivers only the

asked attributes and not whole documents as today.

For instance, if an organization needs to know if you

are older than 65 years, it should ask for this specific

attribute from someone that knows the citizen’s birth

date instead of asking for a complete birth

certificate. This implies to break with PA practices

and that PA information models go to the

information item (attribute) level of detail.

4.4 Incentive to Development

This model has the potential to promote the

development of new citizen-centric tools for

assisting the citizen in e-government transactions by

combining services provided by PA departments and

private companies. Since services are publicly

available, and based in some open technology,

citizens and businesses can develop their own new

ways of interaction with e-government, possibly

more adapted to their specific needs.

4.5 Model Applicability

The model proposed in this paper has been thought

for the provision PA services to citizens (G2C). Its

applicability for scenarios of provision of services to

businesses (G2B) and other government agencies

(G2G) was not considered. Moreover, the model has

not been thought for the provision of mediated

services to elderly or other people that delegate in

others their transactions with government.

5 RELATED WORK

AND CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we presented an e-government model

that supports the provision of life-event services

with the citizen controlling the exchange of his

information between organizations. It is the citizen

responsibility to provide its information to services

requiring it, possibly after obtaining it from services

provided by other organizations. This way, a citizen

has a better control over who has access to his

WEBIST 2011 - 7th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies

498

personal information and for what purposes.

As already mentioned our model is based in the

Information Card Ecosystem (ICE). But ICE is

essentially targeted to provide token information to

access control mechanisms when accessing services,

while we propose its use for the general exchange of

citizen information.

The provision of e-government services centred

in citizen needs is not a novelty. OneStopGov

(http://www.onestopgov-project.org) is an example

of a project addressing citizen-centred e-government

services. Services are provided in active life-oriented

portals that allow the tailoring of services based on

the citizen context and profile. The portal conducts a

dialog with citizen to obtain the specific citizen

circumstances and determine which documents are

to be presented by citizen and which exact service

versions are to be executed (Tambouris & Tarabanis

2008). This same concept is used in our model,

except that the dialog is conducted locally (by the

egWallet), based in a set of rules provided by the

service (“roadmap”).

The concept of a eWallet (electronic wallet) has

been proposed as a tool for the management of

personal information in Internet transactions (Al-

Fedaghi & Taha 2006). However, it is not intended

for the type of transactions we propose. The

egWallet concept is also related with Personal Data

Ecosystem (http://personaldataecosystem.org) as it is

intended to manage data generated by users.

The promotion of citizen and business initiative

for the development of citizen tailored services has

already been proposed by the concept of e-Citizen,

but for development of portals as service mediators

between government and citizens (Filho 2005).

Our model is still a vision; some important future

work is: (i) study and selection of a language to

express the life-events’ “roadmaps”; (ii) Analyse PA

information models and its adequacy to our goals;

(iii) definition of an implementation architecture.

REFERENCES

Al-Fedaghi, S. S. & Taha, M. M., 2006. Personal

Informnation eWallet. In 2006 IEEE International

Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics. Taipei,

Taiwan, pp. 2855-2862.

Bannister, F., 2005. The Panoptic State: Privacy,

Surveillance and the Balance of Risk. Information

Polity, 10(1/2), pp.65-78.

Brooks, L. & Agyekum-Ofosu, C., 2010. The Role of

Trust in E-Government Adoption in the UK. In

Proceedings of the Transforming Government

Workshop 2010 (tGov2010).

Burton, C., 2009. The Information Card Ecosystem: The

Fundamental Leap from Cookies & Passwords to

Cards & Selectors. Information Card Foundation.

Dias, G. & Rafael, J., 2007. A simple model and a

distributed architecture for realizing one-stop e-

government. Electronic Commerce Research and

Applications, 6(1), pp.81-90.

Dutton, W. et al., 2005. The Cyber Trust Tension in E-

government: Balancing Identity, Privacy, Security.

Information Polity, 10(1/2), pp.13-23.

European Commission, 2003. The Role of eGovernment

for Europe’s Future.

Eynon, R., 2007. Breaking Barriers to eGovernment:

Solutions for eGovernment, Deliverable 3.

eGovernment Unit, DG Information Society and

Media, European Commission, (29172).

Filho, A. R., 2005. e-Citizen: Why Waiting for the

Governments? Ifip International Federation For

Information Processing, pp.91-99.

Heeks, R., 2003. Most e-government-for-development

projects fail: how can risks be reduced? In

iGovernment Working Paper Series. University of

Manchester.

Klischewski, R., 2004. Information integration or process

integration? How to achieve interoperability in

administration. In Electronic Government:

Proceedings of Third International Conference,

EGOV 2004. Zaragoza, Spain: Springer, pp. 57-65.

Kubicek, H. & Cimander, R., 2009. Three dimensions of

organizational interoperability: Insights from recent

studies for improving interoperability frameworks.

European Journal of ePractice, (January), pp.1-12.

Kubicek, H. & Hagen, M., 2000. One-Stop-Government in

Europe: An overview. In One-Stop Government in

Europe: Results from 11 National Surveys. Bremen:

University of Bremen, pp. 1-38.

Lau, E., 2003. Challenges for E-Government

Development. In 5th Global Forum on Reinventing

Government. Mexico City, pp. 1-18.

Layne, K. & Lee, J., 2001. Developing fully functional E-

government: A four stage model. Government

Information Quarterly, 18, pp.122-136.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and

Development, 2003. The e-Government Imperative:

Main Findings,

Tambouris, E. & Tarabanis, K., 2008. A dialogue-based ,

life-event oriented , active portal for online one-stop

government: The OneStopGov platform. In The

Proceedings of the 9th Annual International Digital

Government Research Conference. pp. 405-406.

United Nations & American Society for Public

Administration, 2002. Benchmarking E-government: A

Global Perspective, New York: U. N. Publications.

Vintar, M., Kunstelj, M. & Leben, A., 2002. Delivery

Better Quality Public Services Through Life-Event

Portals. In 10th NISPAcce Annual Conference.

Cracow, Poland.

Yildiz, M., 2007. E-government research: Reviewing the

literature, limitations, and ways forward. Government

Information Quarterly, 24(3), pp.646-665.

CITIZEN CONTROLLED EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION IN E-GOVERNMENT

499