SHOULD COMPANIES BID ON THEIR OWN BRAND

IN SPONSORED SEARCH?

Tobias Blask, Burkhardt Funk and Reinhard Schulte

Leuphana University of Lüneburg, Scharnhorststr. 1, 21335, Lüneburg, Germany

Keywords: Sponsored search, Search engine marketing, Paid search, Brand marketing, e-Commerce, Keyword

selection, Branded keywords.

Abstract: Sponsored Search allows companies to place text advertisements for selected keywords on Search Engine

Results Pages (SERPs). The objective of the present research is to determine whether and under what

circumstances it makes sense, in economic terms, for brand owners to pay for sponsored search ads for their

brand keywords. This issue is the subject of a heated debate in business practice, especially when the

company is already placed prominently in the organic search results. In this paper we describe and apply a

non-reactive method that is based on an A/B-test. It was employed in a case study of a European Internet

pharmacy. The results of this study indicate that the use of sponsored search advertising for the own brand

name enables advertisers to generate more visitors (>10%), resulting in higher sales volumes at relatively

low advertising costs even when the company is already listed in first position in the organic part of the

respective SERP.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the information society, Internet search engines

play a key role. They serve the information needs of

their users and are an important source for

advertising companies in terms of customer

acquisition and activation (Jansen and Mullen,

2008). Search engine companies like Google

generate most of their revenue through sponsored

search (Hallerman, 2008). At the interface of

computer science, economics, business

administration, and behavioral sciences, search

engine marketing has been established as an

interdisciplinary research topic and has seen a

growing and diverse number of publications during

the last years (Edelman et al., 2007; Skiera, 2008; H.

Varian, 2007; H. R. Varian, 2009). Selected decision

problems are examined from the perspective of three

stakeholder groups (i) users, (ii) search engines and

(iii) advertising companies (Yao and Mela, 2009).

Beside the optimal bidding behavior in sponsored

search auctions (Kitts and Leblanc, 2004), one of the

key decision problems for advertisers is the selection

of keywords appropriate for their campaigns

(Abhishek and Hosanagar, 2007; Fuxman et al.,

2008).

So far little research has been conducted on the

use of brand names in sponsored search (Rosso and

Jansen, 2010a). What is the subject of a heated

debate in business practice is whether companies

should bid on their own brand name or whether this

only substitutes clicks from organic listings on the

SERP. To answer this question, we apply a non-

reactive experimental method and use it in a case

study of an online pharmacy that is ranked first with

its brand name in the organic search results in

Google (Unrau, 2010).

The contribution of this paper is the development

and application of a method for measuring the

impact of bidding on brand names in a partially

controlled experiment. From a theoretical point of

view, we make a contribution to understanding

keyword selection in blended search. We begin with

a review of the literature on the competitive

importance of brands in search engine marketing.

On this basis we derive four hypotheses which we

examine using the methods described in chapter 4.

In chapter 5 we discuss outcomes and business

implications of this paper and finally give an outlook

in chapter 6.

14

Blask T., Funk B. and Schulte R..

SHOULD COMPANIES BID ON THEIR OWN BRAND IN SPONSORED SEARCH?.

DOI: 10.5220/0003515300140021

In Proceedings of the International Conference on e-Business (ICE-B-2011), pages 14-21

ISBN: 978-989-8425-70-6

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

There are two streams of research which are

important for our work. The first studies bidding

behavior of competitors in sponsored search. The

second stream – blended search – analyses user

preferences for organic and sponsored results as well

as the interactions between them.

2.1 Brand Bidding and Piggybacking

Although brand terms bidding behavior is of great

relevance in business practice, there have only been

very few scientific publications on the topic. As a

first step, a distinction has to be drawn between the

bids on the own brand and those on other companies

brands. Previous research on sponsored search brand

keyword advertising by Jansen and Rosso (Rosso

and Jansen, 2010a), which was based on the global

top 100 brands included in the well-known WPP

BrandZ survey, reveals that 2/3 of the brand names

examined were used by other firms while only 1/3 of

the brand owners analyzed advertise in the context

of their own brand names on SERPs. Bidding on

other companies’ brand names is referred to as

piggybacking, for which three different types of

motivation have been isolated: (i) competitive:

piggybacking by an obvious, direct competitor; (ii)

promotional: e.g. by a reseller; and (iii) orthogonal:

e.g. by companies that offer complementary services

and products for the brand owners’ products. While

retail, fast food and consumer goods brands are

greatly affected by piggybacking, this practice is

rarely observed in the field of luxury brands and

technology (Rosso and Jansen, 2010a; 2010b).

The Assimilation-Contrast Theory (ACT) (Sherif

and Hovland, 1961) and the Mere Exposure Effect

(Zajonc, 1968) are models that offer an explanation

of the circumstances under which bids on one’s own

or third party brand names could be economically

valuable. In sponsored search advertising the use of

other companies’ brand names seems to be

advantageous when the perceived difference

between the own and other brands is low from a

user’s point of view (ACT), while the value of

bidding on own brand terms depends on the degree

of the Exposure Effect, i.e. the display frequency

that a brand needs in order to influence the

purchasing decisions of users positively. Until now

the empirical validations of these models for brand-

bidding have been based on user surveys (Shin,

2009) and can therefore be subject to the problem of

method bias. However, for the first time we are able

to present results that are based on data that were

collected in a non-reactive setup.

2.2 Blended Search

From the search engines’ perspective, the question is

about the extent to which the free presentation of

results in the organic part of the SERP counteracts

their own financial interests in sponsored search as

they generate essential parts of their profits in this

area (Xu et al., 2009). While a high perceived

quality in the organic search results helps search

engines to distinguish themselves from their

competitors and to gain new customers, it is exactly

this high quality in the organic results that may lead

to cannibalization effects between organic and

sponsored results (White, 2008).

From the users’ point of view, the question has to

be asked which preferences and intentions they have

when making their choice whether to use organic or

sponsored results. Depending on their personal

experience of this particular advertising channel and

their motivation to search, Gauzette (Gauzente,

2009) shows that consumers do not only tolerate

sponsored search as just one more channel for

advertising on the Internet but do sometimes even

consider these sponsored results more relevant than

the organic ones. This is particularly true for

transactional-intended queries, i.e. the so-called

commercial-navigational search, in which the search

engine is used instead of manually typing the URL

into the browser’s address bar. The same strong

preference for sponsored results can also be found in

the context of, for advertisers even more attractive,

commercial-informational queries where users,

although they have a strong intention to buy, are

nevertheless still looking for the best matching result

for their specific commercial interest (Ashkan et al.,

2009).

Along with the multiplicity of intentions that

individual users have when typing queries into

search engines, there are significant variances of key

performance indicators (KPI) that search engines

and advertisers pay attention to. Ghose and Yang

(Ghose and Yang, 2008) compare organic and

sponsored search results in respect to conversion

rate, order value and profitability. In fact, the authors

note that both conversion rate and order values are

significantly higher through traffic that has been

generated by sponsored search results than those

generated by visitors that have clicked on organic

results. It seems that the combination of relevance

and the clearly separated presentation of organic and

sponsored results as well as their explicit labeling

are factors that lead to a greater credibility of the

SHOULD COMPANIES BID ON THEIR OWN BRAND IN SPONSORED SEARCH?

15

search engine and thus increases the willingness to

click on the sponsored results, which are often not

inferior to organic results (Brown et al., 2007).

Studies on the interaction between these two

types of results indicate that their simultaneous

presence in both the organic and sponsored results

leads to a higher overall click probability (Jansen,

2007). More specifically, a high similarity between

the content in the respective snippets leads to a

higher click probability in the context of

informational queries (Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et

al., 2010) while users who are searching with

transactional intentions seem to be more likely to

click on one of the results when the similarity is low

(Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et al., 2010). Ghose and

Yang (Yang and Ghose, 2010) confirm this

observation and point out that this effect is much

more pronounced in the context of brand-keywords

with only little competition (e.g. retail brands /

names of online retailers) than it is in a highly

competitive environment.

In conclusion, and in contrast to a widely held

opinion in business practice it has to be noted that

previous research indicates that the placement of

advertisements on SERPs is useful for advertisers

even where the company is already represented in

the organic results for the respective keyword. For

the special - and for e-commerce queries most

interesting - case of commercially intended queries,

these studies indicate that the simultaneous

occurrence in both result lists increases the overall

probability to be clicked. The verification of these

findings to brand terms has however not been

accomplished so far and is the key contribution of

this paper.

3 HYPOTHESES

The following hypotheses are formulated with

reference to the online search and buying process.

We assume that, when a user searches for the brand

name of a company, both organic as well as

sponsored results are displayed. These results

contain links to the brand owner’s website as well as

links to other companies’ websites. The user has

three options to choose from (as shown in figure1):

he may click on one of the two links that lead to the

website of the company or click on a link that takes

him to a different website, which makes him leave

the area of observation of the study.

Figure 1: Hypotheses of this study in the search and

buying process from a user’s perspective.

Due to partial substitution effects, the following

hypothesis is almost self-evident as the studied

brand occupies the first result in the organic part of

the SERP for queries that contain the brand name:

H1: The number of visitors from organic search

results decreases when brand owners engage in

sponsored search for their own brand keywords.

In his paper (Jansen, 2007) Jansen assumes that the

simultaneous appearance in the organic and the

sponsored results has a positive impact on the

overall click rate of the companies’ advertisements.

This leads to:

H2: The overall number of visitors through

brand name queries from a search engine

increases when companies engage in sponsored

search for respective keywords.

It is important to point out again that this statement

is by no means self-evident, since it would be

possible that the sponsored clicks generated through

a brand term advertisement would merely substitute

organic clicks that would come for free when no

sponsored search is employed. In business practice it

is exactly this point that is the subject of an intense

and controversial debate between advertisers,

agencies, and search engines.

In their study (Ghose and Yang, 2008), Ghose

and Yang point out that the conversion rate of

commercial-navigationally intended queries is

higher for sponsored than for organic results.

Consequently, the following hypotheses can be

derived:

H3: The conversion rate of keyword traffic from

own brand keywords decreases when companies

decide not to place sponsored search ads for

these keywords.

Based on hypotheses H2 and H3 and other things

being equal the following hypothesis on the number

of sales and revenue derived from brand oriented

search can be made:

H4: The overall number of sales and the

respective revenue increase when companies bid

on their own brand names in sponsored search.

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

16

Table 1: Brand keyword clicks and revenues (with standard deviations) in the reference period (data are disguised to ensure

confidentiality).

Weekday Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun

Ad status Off On Off On Off On Off

∑ of all

visitors

562.3

± 93.7

543.6

± 99.9

497.2

± 101.7

452.2

± 119.8

376

± 89.2

283

± 69.7

431.6

± 103.2

Revenue

in €

8285

± 2117

7119

± 1924

6855

± 2022

6162

± 1903

4771

± 1630

3843

± 1608

7627

± 2537

4 CASE STUDY

The study covers a 14 day test period in which

sponsored search for brand keywords is switched on

and off on alternate days. Below, the respective

states in the test period are called “ON” (sponsored

search for brand keywords is employed) and “OFF"

days. A full two weeks test period was chosen to

allow us to monitor each weekday in both of the two

possible states to ensure an acceptable consideration

of the well-known weekday variations in e-

commerce. The test period does not contain any

holidays or other predictable events which could be

relevant for the search engine traffic and conversions

in this time span.

The company we study uses Google Analytics to

collect data on the number and origin of users

(organic as well as the sponsored results). In order to

leverage existing data as a reference we decided to

also use Google Analytics for our study. The

reference period (Table 1) stretches from April 2009

to August 2010 with the omission of the test period

which was chosen to be from April 12, 2010 till

April 25, 2010, starting with an "OFF" day

(Monday). The alternation of “OFF" and "ON" in

the test period was executed manually each morning

at eight o'clock.

Google Analytics assigns recognized re-visitors

to the origin of their first visit. For example, a user

who first reached the company's website on an “ON"

day via a sponsored search result would also be

associated with this type of result for his future visits

and will thus be assigned to the sponsored search

visitors regardless of whether he arrives via an

organic search result or by typing the address into

browser manually. This is the main reason why there

are sponsored search visitors on "OFF" days. To

derive statements on the effect of self-bidding, the

data from the test period is compared with a

reference period that has no overlap with the test

period and contains continuous self-bidding

activities for the brand keyword. As will be argued

in the next section, the main question about the data

is whether the results are statistically significant.

Using a Monte-Carlo-Simulation, we examine the

validity of the observations especially with respect

to hypotheses H2.

Even though the applied method does obviously

influence the behavior of involved users and could

therefore be categorized as ‘reactive’ in terms of

social sciences, it shares common criteria with non-

reactive methods since individual users have no

knowledge of the investigation of his behavior.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Testing the Hypotheses

Hypothesis H1 predicts that the placement of

sponsored search ads for the own brand name leads

to a substitution of clicks that would have otherwise

been generated without costs through clicks on

organic results. This is clearly confirmed in the data.

The magnitude and significance of this effect is

clearly illustrated in figure 2. Comparing the

composition of the sum of all clicks generated on

"ON" days with the clicks on those days without

self-bidding activities, we find more than double the

number of organic clicks on "OFF" days (2392

clicks) than on "ON" days (1060 clicks).

It is, again, noticeable, and illustrated in figure 2,

that we find sponsored clicks in the data that were

generated on "OFF" days where we actually would

not expect any. This can be explained by two

effects: first, the status change was made manually

from “ON” to “OFF” and vice versa every day at

eight o'clock in the morning in the test-period so that

sponsored search advertisements were served until

eight o'clock in the morning even on “OFF” days,

accounting for the minor part of these clicks.

Second, as argued before the cookie based tracking

contributes to the occurrence of sponsored clicks on

“OFF” days. It is obvious that the existence of

sponsored search clicks on “OFF” days could never

generate or strengthen but would on the contrary.

SHOULD COMPANIES BID ON THEIR OWN BRAND IN SPONSORED SEARCH?

17

Table 2: Brand keyword visits, conversion rates and revenues in the test period (data are disguised to ensure

confidentiality).

Date

04/1

2

04/1

3

04/1

4

04/1

5

04/1

6

04/1

7

04/1

8

04/1

9

04/2

0

04/2

1

04/2

2

04/2

3

04/2

4

04/2

5

Weekday

Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun

Ad status Off On Off On Off On Off On Off On Off On Off On

Sponsored

visitors

76 376 56 340 64 184 44 436 92 340 108 292 68 252

Organic

visitors

488 204 340 124 292 88 396 176 436 248 304 124 136 96

∑ of all

visitors

564 580 396 464 356 272 440 612 528 588 412 416 204 348

Revenue

in €

8564 5736 4704 6420 3328 3096 3720 8928 7796 6280 5832 4620 1112 7064

Conversion-

rate

23% 19% 22% 23% 19% 16% 12% 24% 23% 17% 17% 19% 10% 36%

weaken the findings that are presented in this paper,

since they tend to blur a potential effect. In

summary, it is clear that these findings are consistent

with the expectation of a substitution of organic by

sponsored search results (H1).

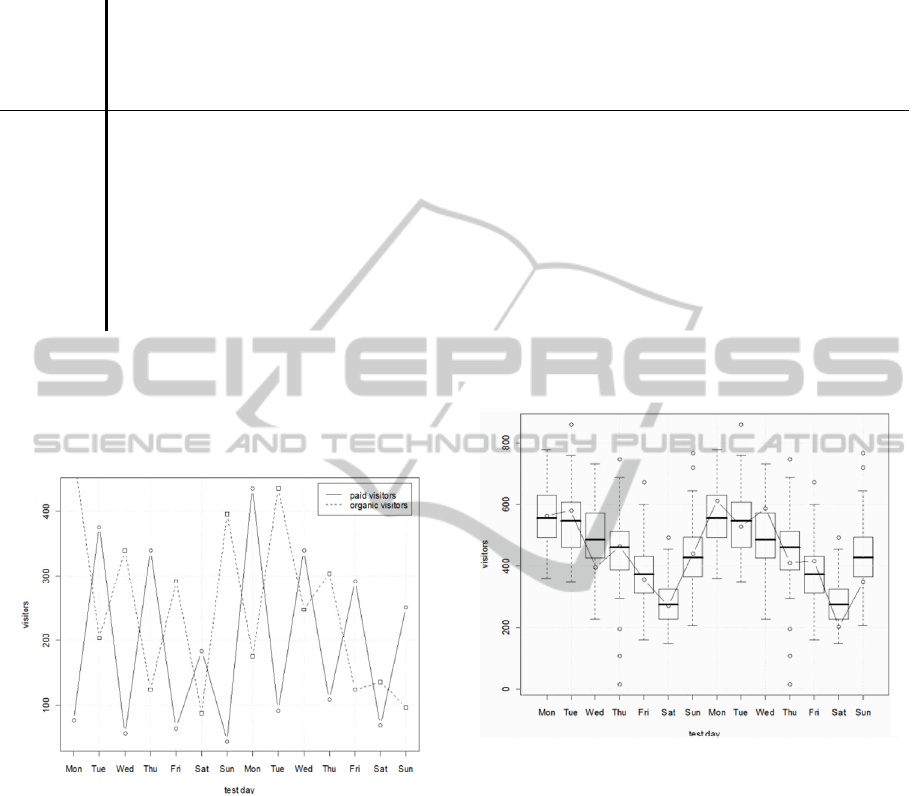

Figure 2: Organic (dashed line) vs. sponsored (solid line)

clicks during the test period.

The second hypothesis H2 deals with the question of

whether the sum of all sponsored and organic clicks

that are generated through the use of the brand name

as keyword in search engines can be increased

through the use of sponsored search advertising. For

this, we compare data from the test period with the

data of the reference period (figure 3).

Beginning with an "OFF" day, figure 3 shows

the values that were generated on a daily basis in the

test period as well as the weekday values of the

reference period, both representing the sum of

sponsored and organic traffic via the brand keyword

from the Google SERPs. The observations of the test

period mainly fall into the 50% percentiles of the

reference period and thus follow the overall

weekday cycle.

Figure 3: Daily sum of all clicks, generated through the

search engine via the brand term in the test period (solid

line) compared to the weekend values in the reference

period. The boxes contain 50% of the values from the

reference period.

However, one can clearly recognize an

overlaying pattern in the test period that is most

likely driven by the alternation of the status of

"OFF" and "ON". Overall, the expected pattern of

more clicks on "ON" days than on the surrounding

"OFF" days could be observed in 11 of 13 possible

daily changes.

What is the likelihood that this pattern occurs by

chance? To answer this question we conduct a

Monte-Carlo-Simulation, in which 1,000,000

random 14-day samples were generated, each

representing a random test period. To generate each

14-day time series, we use the Poisson distribution

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

18

and take weekday means from the reference period

as the mean of the distribution. What is remarkable

is that a fraction of only 0.2% of the randomly

generated test periods fit the observed (alternating)

pattern with at least 11 or more changes. Employing

this measure, it can be concluded with a probability

of 99.8% that the placement of sponsored search

advertisements for the own brand name actually

leads to an increase in the total number of visitors

for this keyword.

From the third hypotheses (H3), we would

expect the conversion rate to be lower on days

without sponsored search advertising than on the

other days in the test. Given the average conversion

rate of 22.7% ± 0.3% in the reference period (figure

4) we find a lower conversion rate for the test period

of 20.1% ± 1.6%, consistent with the study of Ghose

and Yang (Ghose and Yang, 2008), who observed a

lower conversion rate for traffic from organic

listings. It should be mentioned, that due to the low

number of transactions per day (and the

corresponding statistical error) we cannot observe a

consistent difference of the conversion rate between

“ON” and “OFF” days as for the overall clicks

(figure 3).

Figure 4: Conversion rates observed in the test period

(solid red line) with standard errors vs. average conversion

rates with standad errors on a given weekday (solid line)

in the reference period.

Following the proven hypothesis H2 (more visitors

through sponsored search advertising for the brand

name) and the lower conversion rate observed in the

context of hypothesis H3, we expect less sales and

reduced revenues in the test period. In fact, the

revenue via the brand keyword in the test period (€

77,200) is lower than 70% of all comparable 14-day

intervals in the reference period (figure 5).

Considering the revenue trend over the reference

period, the relatively low revenue in the test period

becomes significant since the revenue in the

reference period shows a rising trend as shown in

figure 6 (two-week revenue mean after New Year’s

Eve without the test period: € 99,130 with a standard

deviation of ± € 6,107.89). A similar reduction of

sales can only be observed in the two-week period

around Christmas and New Year's Eve 2009

corresponding to observation point 19 in figure 6.

Thus, we interpret the lower revenue as a

consequence of not employing sponsored search for

brand keywords.

Figure 5: Empirical cumulative distribution of the

revenues in the observation period (14-day intervals,

containing the reference – as well as the test period), the

test period is indicated by the vertical line.

5.2 Economic Impact

We now estimate the economic value of sponsored

search for own brand names. During the test period

each weekday was observed in both states, "ON"

and "OFF". The number of additional visitors can be

estimated by the sum of all clicks on "ON" days

minus the sum of all clicks on "OFF" day in the test

period equal the total number of additional visitors

for one week. In the current study, this results in 380

additional visitors per week. This is a significant

growth of more than 10% achievable through

sponsored search for own brand keywords.

Given the average conversion rate of 22.7%

(reference period) and an average value per

transaction of € 60.88 this leads to an increase in

sales of about € 275,000 per year. The average cost

per click for the brand keyword in the test period

was € 0.03, leading to additional costs of about €

600 per year. To sum up: Even if there were only

very moderate margins for online pharmacies we

SHOULD COMPANIES BID ON THEIR OWN BRAND IN SPONSORED SEARCH?

19

would recommend the use of sponsored search

advertising for brand keywords.

Figure 6: Time series of revenues (14-day intervals)

during the reference period (dashed line), including the

test period (observation point 27, indicated by the vertical

line) and a trend line (solid line).

In general, it seems to be likely that sponsored

search for own brands lead to more visitors and

accordingly to more sales and higher revenues for

the brand owner. The low prices per click for brand

keywords and a higher conversion rate make brand

name advertising economically profitable in the

context of sponsored search.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND

OUTLOOK

It is plausible to argue that users who search for a

specific retail brand name in a search engine have

already decided where their search is going to end

(the website of the retailer). Yet, evidence from this

study suggests that this is not the case for all users.

Some users apparently find other advertisements or

organic results on the SERP more interesting so that

they can get lost for the brand owner if he is not

present in the sponsored search results.

We expect that the extent to which the described

effect occurs in practice for other companies

depends on a number of factors. E.g., the intensity of

competition – defined by the number of competitors

who are also bidding on the brand name – is likely to

have an influence on the observed effect. This is of

special interest, because since September 2010 (in

the European Union) companies can not ban other

advertisers to bid for their brand keywords

(Bechtold, 2011) which will lead to a more intense

competition. In the light of this change the present

research gains in importance for a whole range of

advertisers. Other factors may be the price level of

sponsored search clicks, the reputation and brand

value of the advertiser and product characteristics.

Considerably more research is needed to determine

the extent to which these factors have an impact on

the described effect. Besides that, the authors

currently work on a project that will help to

understand user behavior in this context.

REFERENCES

Abhishek, V., & Hosanagar, K. (2007). Keyword

generation for search engine advertising using

semantic similarity between terms. Proceedings of the

ninth international conference on Electronic

commerce, 89–94

Ashkan, A., Clarke, C. L., Agichtein, E., & Guo, Q.

(2009). Classifying and Characterizing Query Intent.

Proceedings of the 31th European Conference on IR

Research on Advances in Information Retrieval, 578–

586

Bechtold, S. (2011). Google AdWords and European

trademark law. Communications of the ACM, 54(1),

30-32

Brown, A., Jansen, B, & Resnick, M. (2007). Factors

relating to the decision to click on a sponsored link.

Decision Support Systems, 44(1), 46-59

Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil, C., Broder, A. Z., Gabrilovich,

E., Josifovski, V., & Pang, B. (2010). Competing for

usersʼ attention. Proceedings of the 19th international

conference on World wide web - WWW ’10, 291-300

Edelman, B., Ostrovsky, M., & Schwarz, M. (2007).

Internet Advertising and the Generalized Second-Price

Auction: Selling Billions of Dollars Worth of

Keywords. American Economic Review, 97(1), 242-

259

Fuxman, A., Tsaparas, P., Achan, K., & Agrawal, R.

(2008). Using the wisdom of the crowds for keyword

generation. Proceeding of the 17th international

conference on World Wide Web - WWW ’08, 61-70

Gauzente, C. (2009). Information search and paid

results—proposition and test of a hierarchy-of-effect

model. Electronic Markets, 19(2), 163–177

Ghose, A., & Yang, S. (2008). Comparing performance

metrics in organic search with sponsored search

advertising. Proceedings of the 2nd International

Workshop on Data Mining and Audience Intelligence

for Advertising - ADKDD ’08, 18-26

Hallerman, D. (2008). Search Engine Marketing: User and

Spending Trends. eMarketer. Retrieved May 5, 2011,

from

http://www.emarketer.com/Reports/All/Emarketer_20

00473.aspx

Jansen, B. J., & Mullen, T. (2008). Sponsored search: an

overview of the concept, history, and technology.

ICE-B 2011 - International Conference on e-Business

20

International Journal of Electronic Business, 6(2),

114–131

Jansen, B. J. (2007). The comparative effectiveness of

sponsored and nonsponsored links for Web e-

commerce queries. ACM Transactions on the Web,

Volume 1, Issue 1

Kitts, B., & Leblanc, B. (2004). Optimal bidding on

keyword auctions. Electronic Markets, 14(3), 186–201

Rosso, M. & Jansen, B. J. (2010) "Brand Names as

Keywords in Sponsored Search Advertising,"

Communications of the Association for Information

Systems: Vol. 27, Article 6.

Rosso, M. & Jansen, B. J. (2010b). Smart marketing or

bait & switch: competitorsʼ brands as keywords in

online advertising. Proceedings of the 4th workshop

on Information credibility, 27–34

Sherif, M., & Hovland, C. (1961). Social judgment:

assimilation and contrast effects in communication and

attitude change. Yale University Press

Shin, W. (2009). The Company that You Keep: When to

Buy a Competitor’s Keyword. marketing.wharton.

upenn.edu

Skiera, B. (2008). Stichwort Suchmaschinenmarketing.

DBW Die Betriebswirtschaft, (68), 113-117

Unrau, E. (2010) Wechselwirkungen zwischen bezahlter

Suchmaschinenwerbung und dem organischen Index.

Master Thesis, Leuphana University, unpublished

Tweraser, S. (2010). Änderungen der Google-

Markenrichtlinie für AdWords in Europa. Google

Inside AdWords Blog. Retrieved May 5, 2011, from

http://adwords-de.blogspot.com/2010/08/anderungen-

der-google-markenrichtlinie.html.

Varian, H. (2007). Position auctions. International Journal

of Industrial Organization, 25(6), 1163-1178

Varian, H. R. (2009). Online ad auctions. American

Economic Review, 99(2), 430–434

White, A. (2008). Search Engines: Left Side Quality

versus Right Side Profits. Available at SSRN:

http://ssrn.com/abstract=1694869

Xu, L., Chen, J., & Whinston, A. (2009). Too Organic for

Organic Listing? Interplay between Organic and

Sponsored Listing in Search Advertising. Social

Science Research. Austin, Texas

Yang, S., & Ghose, A. (2010). Analyzing the Relationship

Between Organic and Sponsored Search Advertising:

Positive, Negative or Zero Interdependence?

Marketing Science, Vol. 29, No. 4, July-August 2010,

602-623.

Yao, S., & Mela, C. F. (2009). Sponsored Search

Auctions: Research Opportunities in Marketing.

Foundations and Trends in Marketing, 3(2), 75-126

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure.

Pers. Soc. Psycho, 9(2. Part 2), 1-27

SHOULD COMPANIES BID ON THEIR OWN BRAND IN SPONSORED SEARCH?

21