ANALYSIS ON THE SPATIAL VARIATION OF THE CENTER

OF GRAVITY OF INBOUND TOURISM IN CHINA

Yining Chen and Hui Zhang

School of Economics and Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, P.R. China

Keywords: Inbound tourism, Center of gravity (CoG), Spatial distribution, China.

Abstract: This paper examines CoG movement of the chief indicators of inbound tourism in China from 2000-2010.

Three themes guide the analysis. First, the changing CoG of China inbound tourism is calculated and

mapped. Second, the changing inbound tourism size distribution of the 31 provinces is examined. Third, the

provinces are ranked according to their growth rate, and analyse the changing spatial concentration of

inbound tourism. Some generalizations regarding spatial variation are given and future trends for the

balanced development of inbound tourism are briefly discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since the reform and opening up, inbound tourism in

China has been experiencing a rapid development,

and foreign exchange reserve due to international

tourism has been growing at a high speed. The

number of inbound tourists to China of 2010

exceeds 264 millions, and the industry income

brought by inbound tourism reached 51.96 billions

for the same year, being 144 and 224 times

respectively the numbers of 1978, 7.62 and 21.4

times those of 1990, 1.17 and 1.1 times those of

2000. From the beginning of the 21st century,

impacted by SARS, international financial crisis,

China’s exchange reform and various natural

disasters, the growth rate of inbound tourism in

China shrunk, and a negative growth even appeared.

Under the accumulated influences of policies like

File 41 and its implementations, assignment

instructions released by the State Council in 2009,

inbound tourism gained a strengthened position in

the regional economy development. Witnessing the

building of high-speed mass transit system, the

establishment of International travelling island of

Hainan and Touristic reform experiment area of

Guilin, the constructing of local style tourist

destination by the autonomous region of Ningxia,

international interests sites by the region of Xizang

and the like by the region of Xinjiang, inevitable

questions arise: What is the current situation of the

spatial distribution of inbound tourism in China?

How to enhance development the regional tourism

for a more balanced spatial distribution of the

inbound tourism in China? It is based on these

questions that this paper attempts to illustrate the

spatial diversity and diachronic dynamic variation of

the inbound tourism in China.

The center of gravity (CoG) is a concept

developed by Carl Von Clausewitz, a Prussian

military theorist, in his work On War (Carl Von

Clausewitz, 2009). In its military sense, the CoG is

usually seen as the "source of strength"; in its

geometric sense, it is the point in or near a body

upon which gravity can be thought of as acting.

Recently, the CoG was applied to social and

economic research, it was seen as the point of

greatest importance, interest, or activity. Scholars

employ the CoG model to do analysis on metropolis

demographic gravity center movement and

demographic spatial convergence (L. N. Tellier,

1995; G. F. Mulligan, 2005). Lucia Falzon (2006)

brought Bayesian Network algorithm into the

research of military planning gravity center (Y. H.

Bao, 1998). Research involving CoG in China came

about comparatively late, with the subjects varying

from demography gravity center at the primary stage

to spatial gravity center concerning society,

economy and natural resources. Some researchers

analysed the arable land gravity center coal resource

(Y. H. Bao, 1998; J. H. Wang, 2006). Some

441

Chen Y. and Zhang H..

ANALYSIS ON THE SPATIAL VARIATION OF THE CENTER OF GRAVITY OF INBOUND TOURISM IN CHINA.

DOI: 10.5220/0003580604410447

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (SSTS-2011), pages 441-447

ISBN: 978-989-8425-53-9

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

researchers focused on the analysis of the

demographic and economic gravity center

and did

some comparative study on the results (Fan C, 2003;

Y. J. Yu, 2005; Z.X.Feng, 2005; Z.X.Feng, 2006). In

recent years, there has been a shift of attention to

industrial gravity center among domestic scholars

(G. Z. Cao, 2007; J. J. Zhang, 2009; S. M. Wu, 2010;

Wen M, 2004).

The subjects of the current research concentrate

at the macro-economic level, and are limited to the

primary and secondary sector of economy. The

researches revolving economic development and

industry spatial distribution is not seen with obvious

progress, and those on tourism economic gravity

center are very rare. This paper sees each province

(autonomous area, municipality) as the basic

physical unit, calculate and work out CoG

movement of the chief indicators of inbound tourism

in China, in the aim to look inside the spatial

variation and characteristics of the inbound tourism

from an overall perspective, with the help of which

the geographical developing planning and related

policies formulation of the industry of tourism can

be better done.

2 METHODOLODGY

2.1 Data

In the measurement of the gravity centers for

inbound tourism, the coordinates of the capital city

in each province are taken as the economic gravity

center (the capital cities remain geographically static

during the time of research). The fact is more than a

few provinces govern at least two chief touristic

cities, such as Guilin and Nanning in Guangxin

Province, Qingdao and Jinan in Shandong Provice,

Suzhou and Nanjing in Jiangsu Provice, etc., but it’s

quite difficult to acquire data of sub-provincial

areas, and the inbound touristic gravity center tend

to be physically close to the capital city in most

cases. Therefore, it’s feasible and necessary to set

the coordinates of the capital city as the economic

CoG and to do explorative research on the topic. As

to the indicator selecting, consulting the statistics

from 2000 to 2009 from “China Tourism Statistics

Yearbook”, this paper chooses inbound tourism

foreign exchange income as the total amount

indicator. Based on the indicator chosen, inbound

tourism economic center is worked out. Please note

that the calculation is within the Chinese mainland,

Hong Kong, Chinese Taipei and Macaw are not

included.

2.2 Method

The gravity center model being the basis, this paper

analyses the regular patterns of the spatial variation

of the inbound tourism and industrial distribution in

China over the past decade. More specific

description would be: establish a resource data base,

the inbound tourism economic indicators of each

province for the years from 2000 to 2010 included,

then the gravity center model is used to calculate the

gravity center coordinates of inbound tourism for

each year; draw out a scatter diagram and a gravity

center moving line; conclude the reasons for the

inbound tourism gravity centers referring to their

longitudes and latitudes.

2.2.1 CoG Model

Assume that a region consists of n sub-regions

(particle), the longitude and latitude of central city in

the number i sub-region are set as X

,Y

, and T

represents the quantity of certain feature of the

number i sub-region. Certain feature and coordinates

of provinces (autonomous regions, municipalities)

are used to help calculate the CoG of certain feature.

Formula for calculating the CoG coordinates is

X=

∑

X

∗T

∑

T

⁄

(1)

Y=

∑

Y

i

∗T

i

∑

T

⁄

(2)

From the algorithm point of view, there are two

determinants of CoG: geographical location and

feature variation in each area. Now that the

geographical location of each area is assumed to be

same, the CoG variation can reflect the change of

corresponding feature. Due to an uneven developing

level and speed of inbound tourism and related

touristic industries throughout different regions in

China and a huge annual gap, the inbound tourism

economic and industrial gravity centers stay in a

continuously changing state.

2.2.2 Moving Direction of CoG

The CoG moving direction points out the physical

structure variation direction. The CoG of the years i

and i+1 are represented as

A ( X

,Y

) , B (

X

,

Y

). The year i is the starting year, and θ

stands for the shifting angle away from the starting

year when it comes to year i+1. The east is

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

442

considered

0

°

in this paper. The following formula is

used to calculate the angle between two sequential

years:

θ

=arctg

–

(3)

θ stands for the shifting angel of the gravity

center (0

°

< θ < 180

°

), with the east being 0

°

,

counter-clockwise movement means a positive

variation, and clockwise negative. When

θ = 0

°

or θ = ±180

°

, the gravity center moves

horizontally, to the east or the west; when θ=±90

°

,

it moves vertically, to the north or the south; when

0

°

<θ<90

°

, the gravity center moves to the north-

east direction; when 90

°

<θ < 180

°

, it moves to the

north-west; when −90

°

<θ<0

°

, the gravity center

moves to the south-east direction; and to the south-

west when 0

°

<θ<90

°

.

2.2.3 Geographical Shifting Distance of CoG

Formula (4) is used to calculate the gravity center

geographical shifting distance of two sequential

years:

D=C∗

(X

−X

)

+(

Y

−

Y

)

(4)

C=111.111, the ratio between the physical

coordinates (degree) and the graphic distance

(kilometer), X

−X

, Y

−Y

represent the

variation of the gravity center coordinates from the

year i to the year i+1, C*

(X

−X

), C∗(Y

−Y

)

respectively stand for the actual shifting distances

along the longitude and the latitude, thus

∗(

)

∗(

)

stands for the ratio between the variation speed

along the two directions.

When

|

| <1, the gravity center shifting

angel is within the range of (-45º, 45º ), (135 º,

180º), (-135º,-180º), indicating that the variation

speed along the longitude is faster than along the

latitude;

When

|

| >1, the gravity center shifting

angel is within the range of (45 º, 135º), (-45º,

-135º), indicating that the variation speed along the

latitude is faster than along the longitude;

When

|

| =1, the gravity center shifting

angel straddles the diagonal of 45 º and 135 º ,

indicating that the variation speeds at both directions

are the same;

If the shifting direction coincides with the axis,

the gravity center moves along the longitude or the

latitude.

3 GEOGRAPHICAL DISPARITY

AND VARIATION ROUTE OF

THE INBOUND TOURISM IN

CHINA

3.1 Characteristics of Variation of the

In-bound Tourism Spatial

Distribution

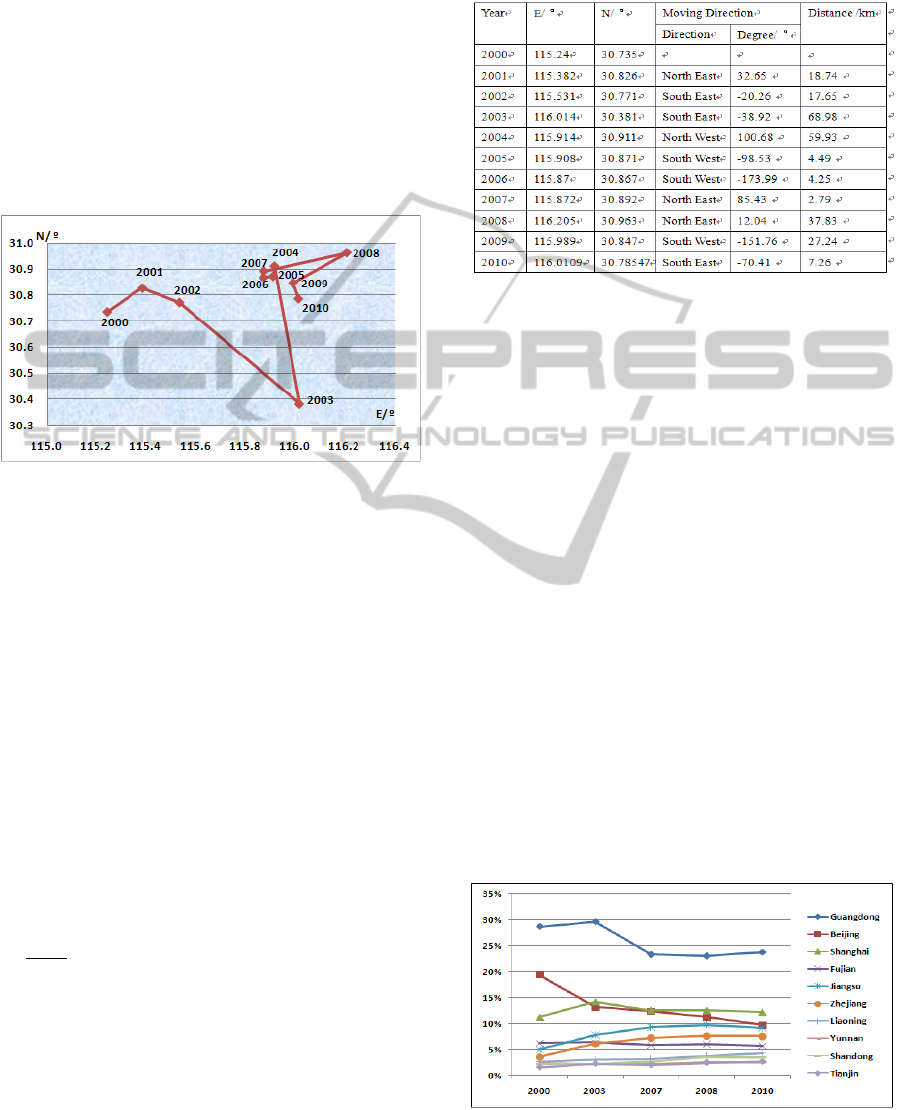

3.1.1 Moving Direction

From the perspective of the moving direction,

starting from 2000, 60% of the movements of the

inbound tourism economic gravity center are

clockwise (negative, as assumed above), the other

40% being counter-clockwise, and no apparent

regular pattern can be found. There is an obvious

eastward tendency in the shifting of inbound tourism

economic gravity center (fig.1, tab.1), as is shown in

Fig1 and Tab1 that the gravity center moves within

the north latitudes of 30.7ºand 30.9º, with the years

of 2003 and 2008 being exceptions. The distinct

situation of these two years might reflect the fact

that inbound tourism is substantially influenced by

the exterior environment.

To look at the issue in details, during the period

between 2000 and 2003, the inbound tourism gravity

center shifts clockwise, revealing a tendency of

moving toward the southeast. The Western

Development Campaign started from October 2000

didn’t alleviate the economic disparity between the

eastern and the western tourism, and the tourism

industry got seriously influenced by the SARS

breakout. The Yangtze River Delta region was an

area that enjoyed a high speed development in

inbound tourism during that period of time (tab2).

The economic gravity center varies within 115.87º-

115.92º of the east longitude, 30.86º-30.92º of the

north latitude during 2004-2007, and annual

distinctions of this period are slight. The movements

ANALYSIS ON THE SPATIAL VARIATION OF THE CENTER OF GRAVITY OF INBOUND TOURISM IN CHINA

443

between 2007 and 2010 remains eastward, with the

direction of the one of 2008 being apparently north

by east, resulting from the influences of the Sichuan

earthquake and Beijing Olympics. In 2009,

《 Instructions on the implementation of Hainan

International Travel Island Building and

Development

》 was released by the State Council

and the development project of the island has been

upgraded to a state strategy, a sign of a larger gap

between the east and the west, a smaller one

between the north and the south though.

Figure 1: China inbound tourism gravity center movement

from 2000-2010.

3.1.2 Shifting Distance

From the perspective of the shifting distance, the

shortest distance of gravity center shifting cor-

responds to the year of 2007, moving by 2.79km,

85.43 º to the north by east, and the longest

corresponds to the 2003, moving by 68.98km,

38.92º to the south by east. Shifting distances in 4

respective years are longer than 20km, reaching

194km, 78% of the total shifting distance, indicating

that the overall gravity center movement slows

down, but the external environment influences are

prominent to inbound tourism in China.

During the studied period of time, the angel of

the gravity center shifting is within the range of (

45º, 135º) or (-45º, -135º), stating that the situation

of

|

|<1 happened in 6 respective years (60%),

indicating a higher variation speed along the

longitude than the latitude from an overall view, and

a fiercer dynamic comparison between the east and

the west than between the north and the south.

Table 1: Direction and distance of China inbound tourism

gravity center movement from 2000-2010.

3.2 Inter-province Comparison of

In-bound Tourism Spatial

Distribution

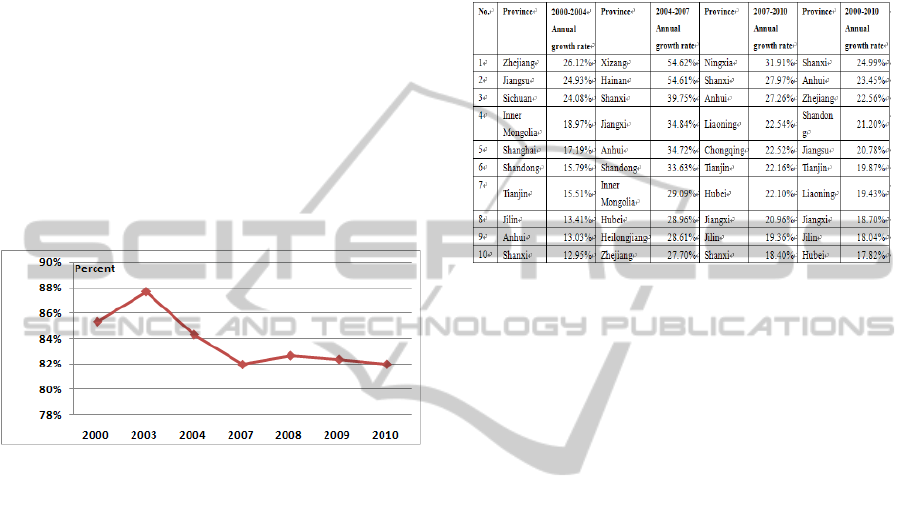

3.2.1 Comparison of the Inbound Tourism

Scale

The list of Top 10 provinces (autonomous region or

municipality) in inbound tourism income

experiences slight changes during 2000-2003, yet it

stays comparatively stable from 2004, with only a

small number of provinces switching the ranking

positions. Starting from the year of 2004, the

international tourism income of Tianjin has been

ranked top 10 countrywide, yet Shanxi and Guangxi,

former top 10 seat-takers, were pushed out of the top

10 circle in the same year. During the studied deca-

de, the provinces among the top 10 in the

international tourism income that bear an obvious

growing proportion are Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Liaoning,

Shandong and Tianjin (fig.2), this might be an

apparent cause for the eastward tendency of the

movement of the inbound tourism gravity center.

Figure 2: Proportion of Top 10 Provinces in international

tourism income from 2000-2010.

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

444

The cumulative proportion of top 10 provinces in

international tourism income declined during 2000-

2010(fig.3). The percentage is 85.34% in 2000, and

climbed to 87.68% in 2003, it decreased to 81.98%

in 2007, which is the lowest one during the past 11

years. The decline of the cumulative proportion of

the Top 10 provinces in international tourism

income reveals that the geographic concentration of

inbound tourism is on the downside. There are some

new and emerging destinations (as Xizang, Hainan,

etc.) coming up because of transportation

development, government supporting polices and

other reasons. Accordingly, the rapid growth rate of

this rising destinations in the west and central region

of China are changing the CoG of inbound tourism

to the southeast slightly in recent years (fig.1, fig.3,

tab.2).

Figure 3: Cumulative proportion of top 10 provinces from

2000-2010.

3.2.2 Comparison of Inbound Tourism

Growth Rate

The annual average growth rates are measured on a

four-period-division basis, the 10 regions with the

highest growth rates in each period are shown in Tab

2 along with the specific figures. The growth rates

are high and uneven, and those during 2004-2007

are the highest. The rates of Sichuan and Hainan

during the same four years are higher than 50%.

From 2007 to 2010, due to the influences of the

financial crisis, growth rates of all areas slow down,

with the one of a western region, Ningxia, being the

highest as over 30%. To compare seeing the country

as a whole, from 2000 to 2010, Shanxi, Anhui,

Zhejiang, Shandong and Jiangsu’s annual average

rates are higher than 20% and are the five highest in

the country.

In the past decade, Gansu province is the only

one holding a negative growth rate of -12.26%, and

the annual average growth rate of Beijing is the

second lowest as 6.19%, while Shanghai and

Guangdong, functioning as the “power sources” for

the tourism industry of the Yangtze River Delta and

the Pearl River Delta, retain annual average growth

rates of 14.67% and 11.65%.

Table 2: Top 10 provinces in international tourism income

growth rate.

3.2.3 Comparison between Regions

Bohai Sea area, Yangtze Delta area and Pearl River

Delta region are the three main region of China

inbound tourism, which has the core city of Beijing,

Shanghai and Guangzhou respectively. In the

beginning of reform and opening up of China, these

areas have seen the fast growth rate of inbound

tourism, but in recent decade, the growth patterns

are different among these regions. Shanghai

surpassed Beijing in 2003 to be the municipality

(province) with the second highest inbound tourism

income countrywide, and three out of the top ten

locate in the Yangtze Delta area, the center of which

is Shanghai, accounting for 30% of the national

inbound tourism income. The proportion of the

foreign exchange income generated by tourism of

Beijing in the national total has been declining since

2000, from 19.32% of 2000 to 9.71% of 2010.

Though the four members (Beijing, Tianjin,

Liaoning and Shandong) from the Bohai Sea area

that surrounds Beijing and Tianjin are among the top

ten list, a gap exists when compared to the Yangtze

Delta area in terms of the growth rate and the total

volume (fig.2, tab.2). The Pearl River Delta region

with Guangdong province as the core area, as a

whole consistently tops the inbound tourism foreign

income chart in the country. The figure of this

region goes down during the period of 2000-2007,

yet its national proportion stays around 23% in

recent years.

ANALYSIS ON THE SPATIAL VARIATION OF THE CENTER OF GRAVITY OF INBOUND TOURISM IN CHINA

445

4 CONCLUSIONS

Base on the previous analysis, in the past decade, in

terms of the shifting direction the inbound tourism

gravity center moves toward the north by east before

2008, and toward the south by west later on; in terms

of the shifting distance, the periods around 2003 and

2008 are when evident movement happens; in terms

of the shifting angel, the variation speed along the

longitude is faster than along the latitude, a

reflection of the situation that the east-west tourism

variation is fiercer than the south-north variation.

Since the gravity center represents a state that takes

the strength coming from all the spots into account,

the gravity center variation mirrors the redistribution

of the strength. Hence in reality it mirrors the

redistribution and variation char-acteristics of the

tourism and related industries of China. Although a

feature of the CoG of inbound tourism started to

move to the south and the west in the development

of the tourism industry in recent years, disparity

between the eastern and western regions is becoming

more and more notable, and the south-eastern coast

clustering overall structure of the inbound tourism

industry stays unchanged.

Having been through more than 30 years of fast

growth, the inbound tourism of the south-eastern

coast area is bound to be engaged in an industry

upgrade. Industry transfer is an important way of

industry upgrade, along with which physical

redistribution of the inbound tourism industry will

come along. Accelerating the inbound tourism

shifting toward the middle and western regions and

the underdeveloped areas in the north means a lot to

enhancing the coordinated development, reducing

the regional development disparity and improving

the industry upgrade in the eastern region. To realize

an even development among the inbound tourism

area and to realize an efficient industry transfer

between regions, first of all, with the high-speed

mass transit network construction in China since

2008, the transportation infrastructure system

requires improvement and expansion in the west and

central region of China, especially the lines between

the international port cities and the central and

western cities, fully bringing out the radiating and

linking effects of the core cities to accelerate the

Chinese tourism industrial development; secondly,

the investment environment of the middle and

western regions and the underdeveloped areas in the

north should be more elaborately established, the

tourism information and service network should be

further enhanced, achieving the paralleling of the

industrial distribution and tourism destination

planning, in the aim of orderly propelling the

tourism industry development in places like Shangri-

La, Ancient Silk Road, Three Gorges, the Qinghai-

Tibet Railroad adjacent areas, the North-eastern Old

Industrial Base, the Bohai Sea area, the Yangtze

River Delta area, the middle region, the Pearl River

Delta area, the coast west to the Taiwan Strait, Beibu

Gulf and the international travelling island of Hainan;

and finally, by means of upgrading the tourism

products realized by encouraging the middle and

western regions to develop eco-tourism and business

conference products, the inbound tourism is able to

develop at a higher speed and gain a stronger risk-

resisting ability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Fundamental

Research Funds for the Central Universities

(No.2011JBM035).

REFERENCES

Carl Von Clausewitz (2009). On War: The Complete

Edition. Wildside Press LLC. p. 144, 151, 253 437,

444.

L. N. Tellier, C. Vertefeuill (1995). Understanding Spatial

Inertia: Center of Gravity, Population Densities, the

Weber Problem, and Gravity Potential, Journal of

Regional Science, Vol.35, p.155-164.

G. F. Mulligan, J. P. Crampton (2005). Population growth

in the world’s largest cities. Cities, Vol. 22, No. 5,

p. 365–380.

Y. H. Bao (1998). Analysis of center of gravity evolution

of arable land and its driving factors in Inner Mon-

golia, Vol.17, No.4, p.47-54

J. H. Wang, etc. (2006).Spatial Distribution and App-

lications of Coal Resource Potential in China. Journal

of natural resources, Vol.21, No.2, p. 225-230.

Fan C, Scott J (2003) . Industrial Agglomeration and

Development:a Survey of Spatial Economic Issues

in East Asia and A Statistical Analysis of Chinese

Regions.Economic Geography, Vol.79, p.354-361.

Y. J. Yu, Y. Q. Lu (2005). Centrality of the Provincial

Cities. Economic Geography, Vol. 25, No. 3, p.

352-357.

Z. X. Feng, J. S. Huang (2005).The Empirical Application

of the Research Method of Gravity Center in

Industries and the Evolution and Characteristics of

Economic Space in China, Social Scientists, Vol.112,

No.2, p.77-83.

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

446

Z. X. Feng, J. S. Huang (2006). Comparison of the

Dynamic Trajectory of Chinese Economic Gravity

Center and its Industrial Gravity Center from 1978 to

2003, Economic Geography, Vol.26, No.2, p.249-254.

G. Z. Cao, T. Liu (2007). Analysis of the Change of the

Employment Distribution in Beijing’s manufacturing,

Urban Development Study, Vol.14, No.6, p. 8-14.

J. J. Zhang, etc. (2009). Dynamic evolution of the center

of gravity of feed industry in China. Cereal and Feed

Industry, No.2, p.31-33

S. M. Wu, etc. (2010). An Analysis of Spatial Distribution

of Manufacturing Industry in China. China soft

science, No.3, p.123-131.

Wen M (2004). Relocation and Agglomeration of Chinese

Industry[J]. Journal of Development Economics,

Vol.73, p.236- 242.

Krugman P (1999). Increasing Returns and Economic

Geography[J]. Journal of Political Economy, Vol.99,

p.357-363.

Kanbur, Anthony J.Venables (2005). Spatial In-equality

and Development [M]. Oxford University Press.

National Tourism Administration of the People’s Republic

of China, “The Yearbook of China Tourism Statistics”

(2000-2009)

ANALYSIS ON THE SPATIAL VARIATION OF THE CENTER OF GRAVITY OF INBOUND TOURISM IN CHINA

447