HOW COMMUNICATION IMPACTS ON THE DEVELOPMENT

OF TRANSACTIVE MEMORY SYSTEM IN TASK-TEAMS?

Yonglin Yang, Yanping Liu and Fangcheng Tang

School of Economics & Management, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing 100044, P.R. China

Keywords: Transactive memory system, Communication, Team.

Abstract: This study examined the effect of different communication modalities on the development of transactive

memory systems (TMSs) in task-teams. We propose that development of TMSs to meet different expertise

and knowledge demands is dependent on communication context and modes. Findings suggest that in task-

teams, informal communication context, face-to-face (FTF) and non-face-to-face (non-FTF) communication

modes are positively related to the development of TMS. The results also show that the effect of

communication context and modes on TMS development is moderated by prior familiarity among team

members. Furthermore, TMS is positively related to team performance. Finally, theoretical and managerial

implications are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Most of the existing empirical research in the

laboratory demonstrates that TMS has powerful

effects for task performance and expertise utilization

(Hollingshead, 1998); (Liang et al., 1995);

(Moreland, 1999); (Moreland & Myaskovsky,

2000). For example, Lewis (2004) argues teams that

develop TMSs are more likely to fully utilize

members’ expertise and realize the value of

embedded team knowledge. Recent field studies also

show that TMSs help ongoing organizational teams

perform well, suggesting that TMS may provide

benefits across a general set of team tasks (Austin,

2003; Faraj & Sproull, 2000).

While communication was viewed as a valuable

tool for the development TMS (Hollingshead &

Brandon, 2003), other researchers argued that

communication never facilitated the development of

TMS (Akgün et al., 2005). These two inconsistent

views make the role of communication process in

the TMS development unclear. In addition, although

researchers have also studied the conditions that

favor the TMSs development, emphasizing the close

relationships and familiarity among group members

(Wegner, 1987) but have failed to analyze what roles

familiarity plays in TMS. It is also not clear from the

literature how the extent of familiarity among group

members influence the relationships between

communication and TMS development.

In this study, we focus on the communication

processes that influence TMSs development. We

believe that by affecting members’ expectations and

interactions, communication processes play a key

role in developing the structure of a TMS. Then, in a

project, combining and integrating members’

expertise become key functions of a TMS, but the

extent to which a TMS facilitates knowledge

utilization and integration depends on the nature and

frequency of group communication processes.

2 COMMUNICATION

PROCESSES AND TMS

DEVELOPMENT

To tap the role of communication in TMS

development, we introduce the extent of familiarity

as a moderator of the relationships between

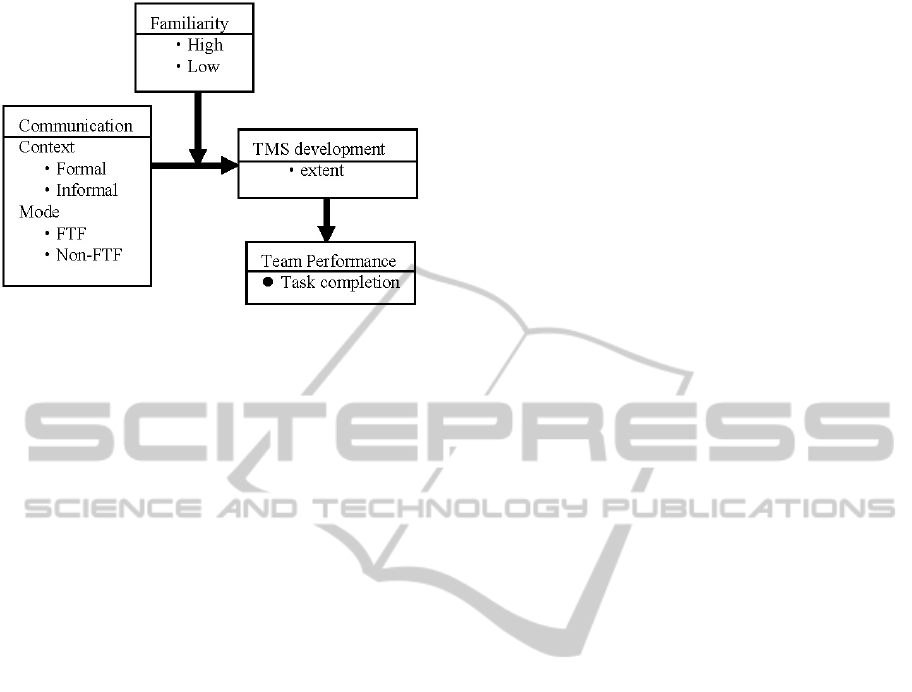

communication and TMS development. We propose

a research model to explain how communication

context, communication modes, familiarity, TMS

development and group performance might be

related in workgroup. Figure 1 summarizes the

relationship among these five factors.

451

Yang Y., Liu Y. and Tang F..

HOW COMMUNICATION IMPACTS ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSACTIVE MEMORY SYSTEM IN TASK-TEAMS?.

DOI: 10.5220/0003595704510454

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (KMKSSC-2011), pages 451-454

ISBN: 978-989-8425-54-6

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Figure 1: Research model.

2.1 Communication Context

Past research demonstrated that providing feedback

about individual skills and opportunities to

communicate created an effective TMS.

The

communications involved both formal and informal

intrateam interaction (Lynn, 1998). An

organization’s communication channels develop

around these interactions within the organization

that are critical to its task.

Generally, formal

communication was exchange via formal meetings

and written documents. Informal communication

involved exchange via hallway interactions and

after-work socialization. So we can gain the

following propositions:

Proposition 1a: The frequency of formal

communication will be positively related to TMS

development.

Proposition 1b: The frequency of informal

communication will be positively related to TMS

development.

2.2 Communication Mode

Communication processes that aid in transactive

retrieval are important for creating a TMS that

facilitates knowledge utilization and integration

during the project. Furthermore, the nature of this

communication may be critical to create a TMS that

helps achieve high performance. Organizational

groups have a variety of communication modes from

which to choose, including face-to-face meetings,

electronic mail communication, and telephone

conversations. According to Griffith and his

colleagues (Griffith & Neale, 2001); (Griffith et al.,

2003), most groups in organizations use a

combination of these, choosing to emphasize one

mode over another depending on the needs of the

task and group. Face-to-face meetings have the

advantage of being the most information-rich

communication medium (Daft & Lengel, 1986)

because they convey both verbal and nonverbal

information (through body language, eye contact,

facial expressions). Information richness is

potentially important for transactive retrieval

processes because members may have encoded

information about others’ expertise in nonverbal

communication that occurred earlier in the project.

Research by Hollingshead suggests the relationships

between communication medium, TMS, and

performance are complex. Results of her studies

imply that a group’s choice between communicating

face-to-face or through a less information-rich

medium should depend on the extent to which a

TMS has already developed.

Groups that have failed

to develop a functional TMS during the project and

communicate predominately through means other

than face to face should be least likely to develop a

TMS capable of facilitating knowledge retrieval,

utilization, and integration. Therefore, we present

the following proposition:

Proposition2a: The frequency of face-to-face

communication will be positively related to TMS

development.

Proposition2b: The frequency of non-face-to-face

communication will be positively related to TMS

development.

3 THE MODERATING EFFECT

OF PRIOR FAMILIARITY

As the antecedent of TMS development, team

member familiarity refers to the degree of prior

interaction between of group members (Harrison et

al., 2003). Familiar members are more likely to have

had a variety of experiences together that give them

a more accurate view on the content, credibility, and

depth of a members’ expertise. So interpersonal

knowledge will be intense in highly familiar teams

and prior experience forms a range of beliefs and

these affected the sharing of information. Gruenfeld

et al. (1996) suggest that familiar members are also

more likely to offer, discuss, and consider unique

information, being more likely than strangers to trust

the source of potentially conflicting information.

Also, their study demonstrated that groups

composed of familiar members with different task-

critical information shared more unique information

and performed better than did teams of strangers

with similarly diverse information. This suggests

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

452

that member familiarity will reduce ambiguity about

how expertise is distributed among members and

facilitate sharing of diverse expertise-both of which

will help elaborate the structure of member-expertise

associations.

Since team member familiarity reduce

uncertainty and anxiety about social acceptance

during the project, and promotes interpersonal

attraction and cohesiveness, while team members

spend little or no time in acquiring members’

expertise and knowledge. In contrast, if members’

initial expertise is overlapping rather than

distributed, member familiarity could delay the

emergence of a TMS. Members with strong ties to

one another are more likely to have redundant

information (Granovetter, 1973) that could be

overemphasized during task discussions (Stasser &

Stewart, 1992). If a group’s initial expertise is

overlapping, high levels of familiarity could make it

even more difficult to distinguish members’ unique

contributions. This could mean delays in defining

who is responsible for what information and

resolving ambiguities about how members’

knowledge fits together. Although familiarity should

help teams with initially distributed knowledge

develop a TMS, high levels of familiarity in teams

with initially overlapping expertise should cause a

TMS to emerge more slowly. Thus, we propose:

Proposition 3a: The effect of formal communication

on TMS development is significantly higher when

familiarity is high rather than low.

Proposition 3b: The effect of informal

communication on TMS development is

significantly higher when familiarity is high rather

than low.

Proposition 3c: The effect of FTF communication on

TMS development is significantly higher when

familiarity is high rather than low.

Proposition 3d: The effect of non-FTF

communication on TMS development is

significantly higher when familiarity is high rather

than low.

4 TMS DEVELOPMENT AND

TEAM PERFORMANCE

The positive influence of a TMS on group

performance is well established in group behavior

literature. Yoo and Kanawattanachai (2001) found

that a TMS has a positive impact on team

performance as shown by profit, ROA, ROE, stock

price, and market share. Dividing up knowledge

responsibilities allows members to focus on

developing deep expertise in their individual

domains, while still maintaining ready access to

task-relevant knowledge possessed by others. When

members are clear about who is responsible for

knowing and remembering what expertise, they can

spend less time searching for necessary information

during task processing. Thus, well-developed TMS

helps group members share and integrate their

expertise quickly and efficiently, helping

organizational groups achieve timely delivery of

their products and services within resource

constraints. TMS development also ensures that a

greater amount of specialized knowledge is brought

to bear on group tasks, resulting in higher-quality

products and services that meet clients’ needs. So

TMS development during the task-performing

should result in the group’s high level of task

completion.

Proposition 4: The extent to which TMS has

developed will be positively related to the group’s

level of task completion.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This study attempts to examine the effect of

communication context and modes on development

of TMS. We expected that communication processes

would affect the development of TMSs. Thus,

communication processes are divided into two parts:

communication context (formal and informal) and

communication modes or types (face-to-face, such

as formal meetings, non-face-to-face, such as

telephone and email). But this study only presents

some propositions because of limitation of length.

Future research should focus on empirical study

based on datasets.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank National Science Fund of

China (NSFC) under contract No.71072028 and the

Fundamental Research Funds for the Central

University under contract No. 2011JBM034 for its

support.

REFERENCES

AkgünA. E., Byrne, J. C., Keskin, H. and Lynn, G. S.,

2005. Transactive memory system in new product

HOW COMMUNICATION IMPACTS ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF TRANSACTIVE MEMORY SYSTEM IN

TASK-TEAMS?

453

development teams. IEEE Transactions on

Engineering Management, 15: 1-17.

Austin, J. R., 2003. Transactive memory in organizational

groups: the effects of content, consensus,

specialization, and accuracy on group performance.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5): 866-878.

Daft, R. L., Lengel, R. H., 1986. Organizational

information requirements, media richness, and

structural design. Management Science, 32(5): 554-571.

Faraj, S., Sproull, L., 2000. Coordinating expertise in

software development teams. Management Science, 46:

1554-1568.

Granovetter, M., 1973. The strength of weak ties.

American Journal of Sociology, 78(6): 1360-1379.

Griffith, T. S., Neale, M. A., 2001. Information processing

in traditional, hybrid, and virtual teams: from nascent

knowledge to transactive memory. Research of

Organization Behavior, 23: 379-421.

Griffith, T. L., Sawyer J. E. and Neale, M. A., 2003.

Virtualness and knowledge in teams: managing the love

triangle of organizations, individuals, and information

technology. MIS Quarterly, 27(2): 265-287.

Gruenfeld, D. H., Mannix, E. A., Williams K. Y. and

Neale, M. A., 1996. Group composition and decision

making: How member familiarity and information

distribution affect process and performance.

Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes,

67(1): 1-15.

Harrison, D. A., Mohammed, S., McGrath, J., Florey, A.

T. and Vanderstoep, S. W., 2003. Time matters in team

performance: effects of member familiarity,

entrainment, and task discontinuity on speed and quality.

Personnel Psychology, 56: 633-669.

Hollingshead, A. B., 1998. Communication, learning, and

retrieval in transactive memory systems. Journal of

Experiment and Social Psychology, 34: 423-442.

Hollingshead, A. B., Brandon, D. P., 2003. Potential

benefits of communication in transactive memory

systems. Human Communication Research, 29(4): pp.

607-615.

Lewis, K., 2004. Knowledge and performance in

knowledge-worker teams: a longitudinal study of

transactive memory systems. Management Science,

50(11): 1519-1533.

Liang, D. W., Moreland R., Argote, L., 1995. Group

versus individual training and individual performance:

the mediating role of transactive memory. Personality

and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21: 384-393.

Lynn, G. S., 1998. New product team learning: developing

and profiting from your knowledge capital. California

Management Review, 40: 74-93.

Moreland, R. L., 1999. Transactive memory: learning who

knows what in work groups and organizations, L.

Thompson, D. Messick, J. Levine, eds. Sharing

knowledge in organizations. Lawrence Erlbaum,

Hillsdale, NJ.

Moreland, R. L., Myaskovsky, L., 2000. Exploring the

performance benefits of group training: transactive

memory or improved communication? Organization

Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82: 117-133.

Wegner, D. W., 1987. Transactive memory: a

contemporary analysis of the group mind, B. Mullen, G.

R. Goethals, eds. Theories of Group Behavior.

Springer-Verlag, New York.

Yoo, Y., Kanawattanachai, P., 2001. Developments of

transactive memory systems and collective mind in

virtual teams. The international Journal of

Organizational Analysis, 9: 187-208.

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

454