A CRITIQUE OF THE BENEFITS STATEMENT 2006/2007 FOR

THE UK NHS NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR IT

Angus G. Yu

Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stilling, U.K.

Keywords: Value-based framework, Project value, Benefits management, Assessment methodology.

Abstract: With all the discussions of value and benefits based approach for managing information technology (IT)

investments, few organizations publish a benefits statement for an actual project or programme. Thus the

Benefits Statement 2006/2007 published by the UK NHS National Programme for IT (NPfIT) provides a

valuable sample for us to inspect and draw lessons from. This paper examines the statement from the

perspective of a value-based framework for project assessment. It is found that the NPfIT benefits statement

is defective for a number of reasons. In addition to an admittedly immature theory of IT value assessment,

the NPfIT authority did not start the programme with a baseline value proposition or a value assessment

methodology. It also failed to make a good use of a centrally prescribed methodology by the UK

government. It even ignored specific benefits estimates suggested by the government’s audit office. Most if

not all of these defects can be attributed to the lack of a coherent conceptual framework for project value

assessment in the NPfIT authority.

1 INTRODUCTION

There are many open questions regarding assessing

value contributions for any IT-based project or

programmes. Is it even possible to give an accurate

account of the value contribution of an IT project? If

it is, what is the overall framework for guiding the

compilation of such an account? This paper

contributes to answering the above questions

through a critique of a published benefits statement

(NHS, 2008) by the National Health Services (NHS)

in the UK on its large scale IT programme. The

critique is based on a value-based framework for

assessing project success.

The main contribution of the paper is to draw

methodological lessons on how the value and

benefits may be measured and presented for large-

scale IT-based projects and programmes. The paper

is organized as follows. First, the value based

framework is briefly introduced and its suitability as

the basis of the critique is discussed. Then the NHS

Benefits Statement 2006/2007 is introduced briefly.

A critique of the publication is then given from a

number of perspectives.

2 THE VALUE BASED

APPROACH

We proceed based on the assumption that an

important channel for information technology to

contribute to organizational value is through various

information systems and the information contained

therein. The design, development and

implementation of the information systems through

project and programme are a necessary part of value

creation process. Therefore, this paper is anchored

on the literature of the value-based approach (in

contrast to the alternatives like the multi-

dimensional approach, see e.g. Shenhar at el., 2001)

for assessing project and programme success. It

should be acknowledged that the value of

information and information systems might be

considered on their own, a project-based view is by

no means unique (Farbey et al., 1992; Love et al.,

2005; Thomas et al., 2007)

There is a degree of consensus for the value-

based approach for project and programme

management (Thiry, 2002; Yu et al., 2005; Winter

and Szczepanek, 2008; Tohidi, 2011). Yu et al.

(2005) proposed a specific value-based framework

for assessing project success which will be the

conceptual basis for the critique in this paper. A

482

G. Yu A..

A CRITIQUE OF THE BENEFITS STATEMENT 2006/2007 FOR THE UK NHS NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR IT.

DOI: 10.5220/0003597804820487

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (EIT-2011), pages 482-487

ISBN: 978-989-8425-55-3

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

brief summary of the framework is given here for

the purpose of this paper. Readers are advised to

refer to the full paper for more details.

Assuming a classic product-based project

lifecycle, Yu at al. (2005) defined the concepts of

net project execution cost (NPEC) and net product

operational value (NPOV) as part of their value-

based assessment framework. At the initial project

execution stage, project cost dominates ancillary

project value, hence the net project cost and value is

designated as NPEC. By the end of project activities,

a product is produced which embodies the value for

the project sponsoring organization. This value is

represented by NPOV which is the sum total of all

the future values of the product, net any cost

associated with realising the values.

The concepts of NPEC and NPOV may be used

for assessing project success. They may be also be

used for describing how a decision is made to go

ahead with a project. These two uses correspond

roughly to “predictive evaluations” and “prescriptive

evaluations” (Remenyi & Sherwood-Smith 1999;

Thomas et al., 2007). However, project evaluation

should not be restricted to these two occasions alone.

There should be an on-going evaluative effort

through a project (Remenyi & Sherwood-Smith

1999). Of course, the earlier the evaluation in a

project lifecycle, the more it depends on estimates

and thus less certain. The later it is in a project

lifecycle, the more likely the factual evidence may

be available. Whenever the evaluation is carried, it

depends on an appropriate conceptual framework to

guide the necessary evaluative activities. A lack of

such a conceptual framework may lead to wasted

efforts and opportunities of project evaluation.

As a large scale IT-based change programme,

The UK Government’s NHS National Programme

for IT (NPfIT) is associated with a huge budget

(more later), and thus is always subject to public

scrutiny in terms of its value and benefits to the

public. The Benefits Statement 2006/2007 (NHS,

2008) is a welcome disclosure of how the

programme authority views the investment and

associated benefits. However, the publication reveals

that the NPfIT authority does not have a coherent

conceptual framework guiding its programme

benefits evaluation. The main motivation for this

paper is to provide a critique to NHS (2008) so that

methodological lessons may be learned for future

similar efforts.

There is a growing body of literature on project

and programme benefits management (Lin &

Pervan, 2003; Ward and Daniel, 2006; Docherty et

al., 2008). The words “value” and “benefit” may be

used in somewhat different ways in different

contexts but for the purpose of this paper, we treat

them as synonyms. The following section provides a

brief background to the programme, mainly based

on NAO (2006, 2008) and NHS (2007).

3 THE NHS NATIONAL

PROGRAMME FOR IT

3.1 Background

The NHS National IT Programme (NPfIT) is a

large-scale IT-based change programme. NPfIT was

initiated in 2002 by the UK central government and

aimed to deliver “four key developments” according

to its initiation document (NPfIT, 2004):

An electronic integrated care records service

including a nationally accessible core data

repository and digital images.

The provision of facilities for electronic

booking of appointments.

The electronic transmission of prescriptions.

An underpinning IT infrastructure with

sufficient connectivity and broadband capacity

to meet future NHS needs.

Other projects are also mentioned, including a

“Picture Archive and Communications Systems

(PACS)”.

At the beginning of NPfIT, the budget was

estimated to be £6.2 billion. By 2007, the budget had

increased to over £12.4 billion (NHS, 2008). Its

value for money has often been called into question.

Hence the NPfIT authority published a Benefits

Statement for the year 2006/2007, attempting to

provide an account of the benefits and thus value of

the Programme (NHS, 2008). This is in response to a

government audit report calling for quantified

financial benefits and service improvements for the

programme (NAO, 2006; Collins, 2008).

The NPfIT has been subject to studies from other

perspectives (see e.g. Hendry et al., 2005; Currie &

Guah, 2007). This paper focuses on the programme

authority’s effort in assessing the value and benefits

of the programme through its publication of the

Benefits Statement 2006/2007.

3.2 The Benefits Statement for NPfIT

2006/2007

The NPfIT Benefits Statement 2006/2007 is the only

such statement available for the programme, despite

the fact that the programme has been in existence

A CRITIQUE OF THE BENEFITS STATEMENT 2006/2007 FOR THE UK NHS NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR IT

483

since 2002. Though the NPfIT authority promised an

annual benefits statement in NHS (2008), no further

report was published in 2009 or 2010. It has been

reported that a draft benefits statement for

2007/2008 does exist (Collins, 2009) but is not

published. There are some benefits statements within

the sub-organizations of NHS but this paper limits

the considerations to NPfIT at the national level.

3.2.1 The Declared Methodology

NHS (2008) provides some details on its adopted

methodology for measuring benefits. The categories

of benefits are given as follows (p28):

cash releasing savings

other measurable benefits to which a financial

value can be attributed

non-measurable benefits which provide local

value.

This is a quite restrictive list of benefits to be

considered, though not entirely out of line with

recommendations from some sources (HM Treasury,

2003; Ward & Daniel, 2006; OGC, 2007). There are

other suggestions to categorise benefits. For

example, Farbey et al. (1992) suggested a scheme

with categories of strategic, tactical and operational

benefits (see also Love et al., 2005). The list of

benefits given by NHS (2008) might be regarded as

tactical and operational. There is no discussion of

strategic and “intangible” benefits in the report.

Even within such a restrictive list, NHS (2008)

only really reported the first category with little

attention paid to the others, as the benefits included

in the report are limited to:

“real savings and other benefits derived from

IT systems and services that have had time to

‘bed in’” (p28)

The report goes on further to clarify that:

“The inevitable time lag between benefits being

realised and evidence being collected and

analysed means that not all benefits realised

from that period have yet been reported.” (p28)

Therefore, NHS (2008) seems to have taken a

historical approach, only including those benefits

which are “real” and have been “realised”. Further,

the report claims that it is based on data from 20% of

the NHS organization involved in the NPfIT. It does

not explain how the sample organizations are

decided and how representative they are.

3.2.2 The Scope of the Programme

NHS (2008) reports roughly the same scope of the

programme as that given in NPfIT (2004) as shown

in Table 1. There is no obvious expansion or

reduction of the scope observed. Arguably, a change

of scope should be accommodated within a value-

based project evaluation methodology since the

increase of scope is theoretically associated with the

increase of cost, and vice versa.

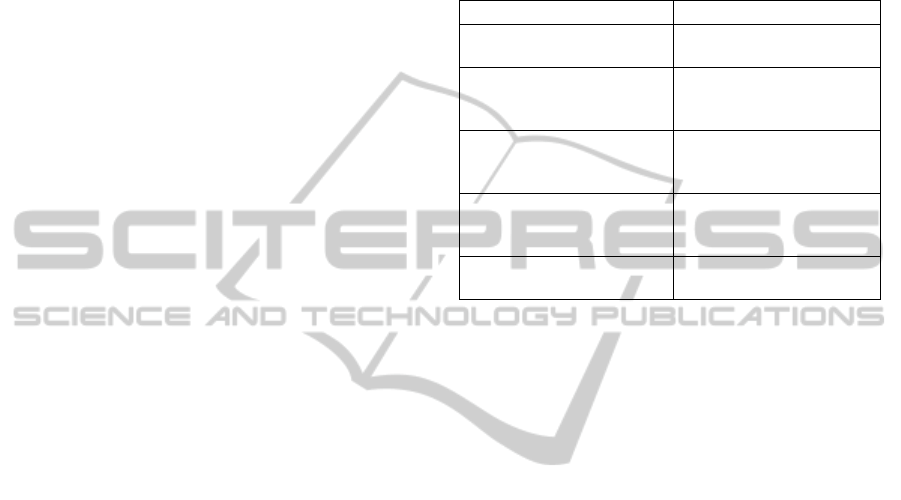

Table 1: Comparing the main programme elements

reported in NPfIT (2004) and NHS (2008).

NPfIT (2004) NHS (2008)

An electronic integrated

care records service

NHS Care Records

Service

Picture Archive and

Communications Systems

(PACS)

Picture Archiving

Communications

Systems (PACS)

The provision of facilities

for electronic booking of

appointments

Choose and Book

System

The electronic

transmission of

prescriptions

Electronic Prescription

Service

An underpinning IT

infrastructure

The National Network

for the NHS (N3)

3.2.3 The Cost

The overall budget for NPfIT is estimated to be

£12.4 billion by 2012. The Benefits Statement

reports a cumulated expenditure of £2.4 billion by

31 March 2007. This is about £2 billion less than the

predicted £4.5 billion (Collins, 2008). Cost is not the

focus of this paper and will not be discussed further.

3.2.4 The Benefits

NHS (2008) reported a figure of benefits totalling

£1,138.1 million. This is made up of three elements.

The first is the reported savings of £208.4 million to

31/03/2007. The second counts further seven years’

savings from 2007 to 2014 based on an annualised

figure of £119.1 million derived from the first

element. The third element is a further adjustment of

£96 million for the whole contract period due to “a

higher level of certainty based on the sample size”.

The explanation in NHS (2008) for this element is

no detailed. Suffice it to say that, while the previous

two elements are more based on evidence, this is

more an estimate, though there is no reason to

question its validity.

4 DISCUSSIONS

This section raises a number of issues regarding

NHS (2008) and its adopted methodology of benefits

assessment and reporting.

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

484

4.1 The Feasibility of Value Assessment

There are clearly concerns on how feasible it is to

conduct a full assessment of the value contribution

of an information system to a business organization

(Remeni, 2000; Love et al., 2005). Common reasons

given include a) cost and benefits change and evolve

over time and some benefits tend to be intangible; b)

managers do not understand the importance of the

investment evaluation process or the concepts

involved; and c) organisational problems (such as

lack of time, management support, and

organisational structure) hindering the evaluation

process (Thomas et al., 2007). However, there are

likely to be more fundamental reasons. A piece of

equipment (e.g. an automated production line) in a

business represents an investment, just like many

projects. The value contributions of capital assets to

a business is captured at sales and are recorded in

the accounts as a whole, not always discernable for

each asset. The accounting system simply treats

capital assets as one of the inputs into an operational

black box. It is difficult to separate the contributions

made by each input. It is so difficult that it might be

counter-productive considering the cost involved.

The activity-based-costing (ABC) method is one

attempt to isolate value contributions from different

inputs. Its success has been rather limited (Katz,

2002; Agndal & Nillson, 2007). Even the ABC

method does not attempt to isolate the value

contributions from every input. It regards some

activities simply as “business sustaining” (Drury,

2007, p231). While further research should be

encouraged to see how the ABC method can help

evaluate projects, the cost and benefit of doing so

should be assessed at the same time.

However, a value assessment is compulsory at

the project initiation stage. Without a full value

assessment, how could any project investment

decision be taken? Even a “business sustaining”

investment has its attached value if we believe

everything can be measured (Hubbard, 2007). The

important thing is to document whatever assessment

assumptions and methodology used so that they may

be peer reviewed both before and after project go-

ahead decisions on a continuous basis.

It has to be acknowledged that with our current

understanding of the economics of information

(Remenyi, 2000), not all benefits can be

meaningfully separated from other sources of value

contributions and measured accordingly (HM

Treasury, 2003). In other words, the theory of

benefits measurement for IT investment is simply

not mature enough. For this reason, NHS (2008) is a

useful and courageous attempt.

4.2 The Baseline for Value Assessment

This section aims to address the question of how a

project assessment may be linked into the initial

business case (IBC). An IBC should provide a

baseline in terms of project scope, cost, time and

value propositions as well as project expenditure.

Assuming that the project sponsor is rational, the

estimated project value should exceed the total

project cost. In the language of Yu et al. (2005), the

initial estimated NPOV (V

0

) should exceed that of

NPEC (C

0

) in order that a project may be authorised

to proceed. It stands to reason that any assessment of

the project value should be benchmarked against V

0

.

However, this is not the case with NHS (2008), in

which the IBC is not mentioned. This is clearly an

oversight in NHS (2008), demonstrating the lack of

a clear conceptual framework within the NPfIT

authority in constructing the benefits statement.

There is a specifically documented overall business

case (NPfIT, 2004) and individual business cases for

constituent projects within the programme.

However, the IBC for the programme (NPfIT,

2004) is itself lacking in necessary details. In

addition to providing baseline value propositions, an

IBC should also make reference to a methodology

on assessing project benefits. The same

methodology should then be used at different project

stages to ensure consistency. The IBC for NPfIT

does not make reference to such a methodology.

4.3 Methodology of Assessment

Considering that NPfIT is undertaken within the UK

government where useful ideas for benefits

measurement have originated (HM Treasury, 2003;

OGC, 2007), the NPfIT authority could have made

use of readily available methodologies like HM

Treasury (2003). As a major government run

programme, there is really no need to re-invent a

methodology for benefits assessment. There is even

less excuse not to apply it when it is readily

available. It would be better of course for the

programme authority to have adapted guidelines in

HM Treasury (2003) to its circumstances. After all,

any large-scale programme has its specific

assumptions and circumstances that a general

methodology will not be able to cover. There is no

evidence that either the programme’s IBC (NPfIT,

2004) or its benefits statement (NHS, 2008)

articulated a coherent methodology of assessment.

A CRITIQUE OF THE BENEFITS STATEMENT 2006/2007 FOR THE UK NHS NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR IT

485

4.4 The Actual vs. the Estimates

According to Yu et al. (2005), value assessment for

a product-based project may be undertaken at any

time, either during the project lifecycle or

afterwards. The earlier the assessment is undertaken,

the more it is based on estimates. The later it is in

the project-product lifecycle, the more it may be

based on actual evidence. Whenever the assessment

is undertaken, it is important to take account of both

the actually realised value and the future expected

value so that the sum total of the benefits may stay

relatively stable.

The evidence is that the authors of NHS (2008)

take a somewhat contradictory position in dealing

with this aspect of assessment. On the one hand,

NHS (2008) claims that it only includes those

benefits which are “real” and have been “realised”.

On the other hand, the report does extrapolate the

reported benefits to seven future years.

Following the suggestions above, the NPfIT

authority should have maintained an account of

“expected benefits”. As these benefits are realised,

they can be moved to an account of “realised

benefits”. The total of the two should stay more or

less stable.

4.5 Cost Savings vs. Value

Contributions

The figures reported in NHS (2008) are almost

exclusively based on “cash releasing savings”,

despite other acknowledged categories in its

methodology (see Section 3.2.1). While cost saving

may be relatively easy to count, it may not even be

the most important reason for undertaking a project.

Following an audit of NPfIT, NAO (2006)

acknowledged (p2):

“The Programme has the potential to generate

substantial benefits for patients and the NHS.

The main aim is to improve services rather than

to reduce costs.”

If the focus is restricted to cost savings and

neglects other benefits, it may easily lead to the

impression that the programme cost exceeds its

benefits when it may not be the case. This is what

happened with NHS (2008). With a programme

budgeted to cost £12.4 billion, the benefits statement

is only able to show benefits of £1.138 billion.

Compared with counting cost savings,

measuring “strategic” and “intangible” benefits of a

project is considerably more challenging. However,

it is not entirely impossible. In fact, NAO (2006)

provided helpful estimates of “patient safety benefits

expected from the Programme” (p26):

£2.5 billion as the human value of preventable

fatalities from medication errors arising from

inadequate information about patients and

medicines.

A large proportion of the £500 million spent

each year on treating patients who are harmed

by medication errors and adverse reactions.

A reduction in the payments by NHS Trusts

each year (approximately £430 million each

year) for settlements made on clinical

negligence claims.

Assuming the first figure is on an annual basis

like the other two, and further assuming that the

introduction of better information systems by NPfIT

can reduce these costs by 50%, the savings could

add up to £17.15 billion over 10 years. This is

considerably more than the cost savings reported in

NHS (2008). Patient safety is one of the reasons for

undertaking NPfIT according to its initiation

document (NPfIT, 2004). However, NHS (2008)

made no effort in quantifying these benefits.

5 CONCLUSIONS

With all the discussions of value and benefits based

approach for managing information technology

investments, few organizations publish a benefits

statement for an actual project or programme. For

this reason, NHS (2008) provides an excellent

opportunity for us to see a large-scale IT-based

change programme’s value assessment in practice.

This is particularly so since NHS (2008) was

produced within an environment where the thinking

on benefits management and “value for money” is

strongly advocated (HM Treasury, 2003; NAO,

2006; OGC, 2007). However, NHS (2008) as a

benefits statement is defective for a number of

reasons. First of all, an important underlying reason

is perhaps that the theory of benefits measurement

for IT investment is simply not mature enough.

However, it is useful for NPfIT to publish such a

statement so that lessons can be learned from it.

Secondly, despite all the discussions of value

management and benefits assessment, the NPfIT

programme was started without a baseline value

proposition or a value assessment methodology

specified in the initial business case. Thirdly, while

the NPfIT authority does not have its own

methodology, it failed to make a good use of a

centrally prescribed methodology by the UK

government. As a result, NHS (2008) focused on a

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

486

narrow range of benefits, missing the opportunity of

providing a proper account of the value propositions

of the programme. The report even ignored specific

estimates suggested by the government’s audit

office. Most if not all of these defects can be

attributed to the lack of a coherent conceptual

framework for project value assessment in the NPfIT

authority.

REFERENCES

Agndal, H. and Nilsson, U. (2007) Activity-based costing:

effects of long-term buyer-supplier relationships,

Qualitative Research in Accounting Management, vol.

4, no. 3, pp222-245.

Collins, T. (2008) NPfIT spending £1.5bn less than

expected._http://www.computerweekly.com/blogs/pub

lic-sector/2008/03/npfit-spending-15bn-less-than.html.

Collins, T. (2009) Ministers sit on draft NPfIT report,

http://www.computerweekly.com/blogs/public-

sector/2009/09/ministers-may-sit-on-draft-npf.html.

Currie, W. L. and Guah, M. W. (2007) Conflicting

institutional logics: a national programme for IT in the

organisational field of healthcare, Journal of

Information Technology, vol. 22, pp235-247.

Doherty, N. F., Dudhal, N., Coombs, C., Summers, R.,

Vyas, H., Hepworth M. and Kettle, E. (2008)

Towards an Integrated Approach to Benefits

Realisation Management – Reflections from the

Development of a Clinical Trials Support System, The

Electronic Journal of Information Systems Evaluation,

vol. 11 (2), pp. 83-90.

Drury, C. (2007) Management and Cost Accounting,

Cengage Learning.

Farbey, B., Land, F. and Targett, D. (1992) Evaluating

investments in IT, Journal of InformationTechnology,

vol. 7, pp109-122.

Hendy, J. and Reeves, B. C. and Fulop, N. and Hutchings,

A. and Masseria, C. (2005) Challenges to

implementing the National Programme for

Information Technology (NPfIT): a qualitative study.

British medical journal, 331 (7512). pp. 331-336.

HM Treasury (2003) Appraisal and Evaluation in Central

Government. HM Treasury.

Hubbard, D. W. (2007) How to Measure Anything:

Finding the Value of ''Intangibles'' in Business, Wiley.

Katz, D. M. (2002) Activity-Based Costing,

http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/3007694.

Lin, C. and Pervan, G. (2003) The practice of IS/IT

benefits management in large Australian

organizations, Information & Management, 41 (1),

pp13-24.

Love, P. E. D., Irani, Z., Standing, C., Lin, C. and Burn, J.

M. (2005) The enigma of evaluation: benefits, costs

and risks of IT in Australian small-medium-sized

enterprises, Information & Management, vol. 42, no.

7, pp947-964.

NAO (2006) The National Programme for IT in the NHS.

HC 1173, Session 2005-2006, The National Audit

Office, London.

NHS (2008) National Programme for IT in the NHS:

Benefits Statement 2006/07, National Health Service,

http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/200808211

11207/http://www.connectingforhealth.nhs.uk/about/b

enefits/statement0607.pdf.

NPfIT (2004) National Programme Initiation Document,

NHS National Programme for IT.

OGC (2007) Managing successful programmes, 3rd edn,

Office of Government Commerce, Stationery Office.

Remenyi, D. (2000) The elusive nature of delivering

benefits from IT investment, Electronic Journal of

Information Systems Evaluation, vol. 3, no. 1, pp1-10.

Remenyi, D. and Sherwood-Smith, M. (1999) Maximise

information systems value by continuous participative

evaluation, Logistics Information Management, vol.

12, no. 1, pp14-31.

Shenhar, A. J., Dvir, D., Levy, O. and Maltz, A. C. (2001)

Project Success: A Multidimensional Strategic

Concept, Long Range Planning, vol. 34, no. 6, pp699-

725.

Thiry, M. (2002) Combining value and project

management into an effective programme

management model, International Journal of Project

Management, vol. 20, no. 3, pp221-227.

Tohidi, H. (2011) Review the benefits of using value

engineering in information technology project

management, Procedia Computer Science, vol. 3,

pp917-924.

Thomas, G., Seddon, P. B. and Fernandez, W. (2007) IT

Project Evaluation: Is More Formal Evaluation

Necessarily Better? PACIS 2007 Proceedings.

Winter, M. and Szczepanek, T. (2008) Projects and

programmes as value creation processes: A new

perspective and some practical implications,

International Journal of Project Management, vol. 26,

no. 1, pp95-103.

Ward, J. & Daniel, E. (2006) Benefits management:

delivering value from IS & IT investments. Wiley.

Yu, A. G., Flett, P. D. and Bowers, J. A. (2005)

Developing a value-centred proposal for assessing

project success, International Journal of Project

Management, vol. 23, no. 6, pp428-436.

A CRITIQUE OF THE BENEFITS STATEMENT 2006/2007 FOR THE UK NHS NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR IT

487