MITIGATE SUPPLY RISK IN SUPPLY CHAIN

Xiaoyu Yang and Shaochuan Fu

Schoole of Economics and Management, Beijing Jaotong University, Beijing, China

Keywords: Disruption Risk Management, Supply Chain, Supply Risk, Multi-supplier.

Abstract: As one of the most important part of supply chain, the supply disruption has more influence than other

disruptions. Once the supply disruption occurs, that may lead to serious consequences; even break the whole

supply chain. This paper analyses the composition of supply risk, addresses an effective method to mitigate

supply risk, i.e., dual-supplier or multi-supplier supply model. In order to choose suppliers for the whole

supply chain, a mathematical model is developed and verified by a numerical example.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the developing of business model, such as

procurement of corporate globalization, outsourcing

non-core business, single-source supply and lean

supply, the supply chain gets longer in the space,

while shorter in time. These changes increase the

possibility of disruption. And the growing

perturbations of external elements like natural

disasters, terrorism, war, epidemics, computer

viruses, economics fluctuations, makes the supply

chain more fragile, and the probability of disruption

higher.

Procurement is the leading force of “upstream

control” overall supply chain. Supply disruptions

may bring great loss to the enterprise and the whole

supply chain. Take the year 2000 lightning incident

in Albuquerque, New Mexico as an example (R.

Eglin, 2003).The incident catastrophically destroyed

a Phillips Electronics semiconductor plant, which

was Ericsson’s single supplier. As a result, when the

plant had to shut down after the fire, Ericsson had no

other sources of microchips and ultimately lost $400

million in sales. Due to such negative influence of

supply disruptions, large numbers of researchers

have started to investigate how to mitigate disruption

risks in a supply chain

Most supply chain disruptions can be broadly

classified into three categories, supply-related,

demand-related, and miscellaneous risks (Oke and

Gopalakrishnana, 2009). Supply disruptions can be

defined as unforeseen events that interfere with “the

normal flow of goods and (/or) materials within a

supply chain” (Craighead et al., 2007). Supply

disruption occurs when suppliers could not fill the

orders placed with them. Supply risks could affect or

disrupt the supply of products or services that the

supply chain offers to its customers potentially.

Supply disruptions has various causes, including

natural disasters, equipment breakdowns, labor

strikes, political instability, traffic interruptions,

terrorism and so forth(S. Chopra, M. Sodhi,2004).

Supply disruptions may cause immediate or delayed

negative effects on procurement firm performance

over the short and (/or) long-term, depending on the

severity of the disruption and the recovery

capabilities of procurement firm (Sheffi and Rice,

2005). While revenue loss from supply disruptions

may stem from the inability to meet demand and

inventory mark-downs, “expediting, premium

freight, obsolete inventory, additional transactions,

overtime, storage and moving, selling, and penalties

paid to customer” make operating costs higher

(Hendricks and Singhal, 2003).

Recently supply disruption management received

increasing attention from both industry and

academia. There are a number of literatures about

supply disruption management. Jian Li, Shouyang

Wang investigated the sourcing strategy of a retailer

and the pricing strategies of two suppliers in a

supply chain under an environment of supply

disruption( Jian Li, Shouyang Wang,2010). Tomlin

went beyond the existing literature by explicitly

modelling the trade-off sand limitations inherent in

mitigation and contingency strategies (Tomlin,

2005). Then he considered a model that a firm may

order from a cheap but unreliable supplier and (/or)

an expensive but reliable supplier. He examined the

544

Yang X. and Fu S..

MITIGATE SUPPLY RISK IN SUPPLY CHAIN.

DOI: 10.5220/0003608105440549

In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (IAST-2011), pages 544-549

ISBN: 978-989-8425-55-3

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

firm’s optimal strategy is to manage supply

disruption. He also investigated the influence of the

firm’s attitude towards risk on mitigation and

contingency strategies for managing supply

disruption risk (Tomlin, 2006). Suppliers’ responses,

such as their pricing strategies, are also crucial

factors that impact the supply chain. The wholesale

price setting problem has been extensively studied in

the literature. Recent literatures gave the optimal

pricing strategies of the suppliers under different

scenarios (Lariviere and Porteus 2001; Wang and

Gerchak 2003; Tomlin 2003; Bernstein and DeCroix

2004; and Cachon and Lariviere 2001). Game

analysis of supply chains is another direction of the

study about supply risk management. Papers using

cooperative game theory to study supply chain

management are much less prevalent, but are

becoming more popular (Cachon and Netessine,

2004). Scott C. Ellis, Raymond M. Henry, Jeff

Shockley, operationalized and explored the

relationship between three representations of supply

disruption risk: magnitude of supply disruption,

probability of supply disruption, and overall supply

disruption risk. They also showed that both the

probability and the magnitude of supply disruption

are important to buyers’ overall perceptions of

supply disruption risk (Scott C. Ellis, Raymond M.

Henry, Jeff Shockley, 2009). Xueipng Li, Yuerong

Chen, developed a simulation model for such an

inventory system and investigated the impacts of

supply disruptions and customer differentiation on

this inventory system. (Xueipng Li, Yuerong Chen,

2009).Due to the complexity of supply risk

management, in this paper we talk about a method to

mitigate the risk, i.e., dual-supplier or multi-supplier.

Furthermore we apply a mathematical model to

choose the right suppliers. We believe the model

developed within this paper may serve as the basis

for future research about supply risk management.

The remainder of this paper is organized as

follows. Section 2 introduces the composition of

supply risk and one method to mitigate the supply

risk, i.e., supply mode of dual-supplier or

multi-supplier. Section 3 presents a mathematical

model for buyers to choose the right suppliers, and

numerical results are presented to illustrate the

theoretical results. Conclusions are given in Section

4.

2 SUPPLY RISK

Supply risk is the probability of supply accident. It

stems from the upstream enterprises of the supply

chain member companies, including potential or

actual disruption of raw materials, spare parts, and

information flows in supply chain. Supply risk can

be led to by individual suppliers, or by the elements

of whole market. Problems of individual supplier

may be caused by natural disaster, failure respond to

fluctuations of demand, quality problems in the

production process, failure to keep up with the

requirements of technological development and so

on. Problems of whole supply market may relate to

patent issues or market capacity constraints.

2.1 The Composition of Supply Risk

Supply risk consists of supply disruption risk and

supply delay risk.

Supply disruption risk mainly comes from

exogenous variables in the supply chain system.

Natural disaster: earthquake, hurricane, flood,

snowstorm, epidemic, lighting;

Operational incidents: supplier’s bankruptcy,

equipment trouble, information infrastructure

close to collapse;

Political instability: labor disputes, war,

terrorism;

Single-source supply risk: dependence on

single source supply and optional alternative

suppliers’ capacity and responsiveness.

The larger the network is and the longer the

route is in the supply chain information system, the

greater the threat of supply disruption is. In addition,

due to the high use of resources or the lack of

flexibility, the delayed flow of materials and supply

delay risk often occurs when a supplier can not

respond to changes in demand.

Supply delay risk caused by the inherent

uncertainty of supply of the system, mainly comes

from production risk, inventory risk, product service

level risk, technology risk, production quality

problems and systemic risk.

Production risk: capacity utilization, capacity

cost, capacity flexibility, production and

technology lags behind competitors;

Inventory risk: lot quantity, mixed changes in

species, stock retirement rates, holding cost

and uncertainty of supply;

Product service level risk: products can not

meet the needs of the number of shipments,

transportation or distribution, lead time and so

on;

Quality risk: poor quality of supply resources;

Technology risk: changes of manufacturing

technique and product design lead to

MITIGATE SUPPLY RISK IN SUPPLY CHAIN

545

production and technology lags behind

competitors;

Systemic risk: risk of system network

expansion and data security of information

(hacker, virus, non-involvement).

Since production can only increase or decrease

over time, one strategic choice could be build excess

capacity. However, excess production capacity will

damage the financial performance, generate

production capacity risk. Inventory risk comes from

the customers’ the fluctuation in demand of the

suppliers’ lot quantity and product variety, out of

stock and excess inventory obsolescence for

example. Product service risk comes from that

products can not meet the needs of the number of

shipments, transportation or distribution and the lead

time. Risk about quality includes the maintenance of

assets, the damage occurred in transit, and the lack

of quality principle and technical training.

Technology risk includes the risk of improvement of

current technology and giving up development

efforts.

2.2 Methods to Mitigate Supply Risk

There are several methods to mitigate supply risk,

such as design a robust supply network, improve the

flexibility of suppliers, ant alter the procurement

path, flexible logistics (transportation of multi-mode

or multi-carrier or multi-route). One proven method

is supply mode of dual-supplier or multi-supplier.

A single source of supply means the buyer

define, discuss and purchase services with single

service supplier. This is a very popular approach,

because it is simple and quick, and can reduce the

purchase cost. And companies can get the best price

when companies and suppliers achieve a close

working relationship. But a single source of supply

will lead to supply security problems in many ways.

For example, if suppliers met special evens like fires

and other accidents, that will lead to supply

disruption; if suppliers shorted of production

capacity or can not product timely, that will lead to

supply disruption. Enterprises adopt a single source

of supply, some because of low cost, and some

because of the lack of qualified alternative suppliers.

When people noticed the importance of prevent

the influence of short supply, walkout and other

emergency, dual-supplier or multi-supplier

procurement becomes an acceptable choice. There

are some advantages of multi-supplier procurement.

First is a reserve of resources available to ensure the

companies can maintain their competitiveness. The

second is the company will no longer restricted by a

single supplier. The third is that the quantity of

supply can be greater guaranteed. When suppliers

competed with each other, buyer can get more

advantages, such as lower costs, promotion of

service and quality.

Dual-supplier or multi-supplier procurement

means there are two or more than two suppliers. The

first supplier is the main supplier with high

efficiency and low transaction cost to satisfy the

demand. The second (and others except the first one)

supplier is used to satisfy the demand variation to

adapt the restrictions of low or high capacity, with

higher price. Flexible procurement strategy enables

enterprises to cope with a temporary supply chain

disruption. But the development of suppliers is often

difficult, managers should recognize the long-term

strategic significance of development of suppliers,

then choose the right suppliers.

3 CHOOSE THE RIGHT

SUPPLIERS

3.1 Model

Here we consider the situation where multiple

suppliers supply for one enterprise. As the buyer, we

use decision theory to choose the main supplier and

the second or other suppliers.

Encode the suppliers and the risk indicators. Let

S

i denote the optional supplier i, Ei denote the risk

indicator i, and P

i denote the weight of Ei. Define

summation of P

i is 1. If choose supplier i, each risk

indicator’s evaluation score is a

ij.

Define six risk indicators:

Probability of supply risk: the smaller the

probability of risk, the better;

Harmful levels of supply risk: the smaller the

harmful level of risk, the better. Indicators

evaluated by five levels: very serious, severe,

general, not too serious, and not serious ;

Financial support: the more financial support,

the better. For example received financial

support based on national or industry policy

and investment guidance;

Allowable time to deal with risks: it denotes the

time how long be allowed to respond to

reduce the damage of risk. The longer, the

better;

Number of affected units: the less the affected

units after the risk occurred, the better;

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

546

Risk management mechanism: the more perfect

a risk management mechanism, the better.

Indicators evaluated by five levels: very well,

perfect, general, not sound, very sound.

Quantitative indicators directly obtained from

data, qualitative indicators rely on experts’

judgments. Generally, subjective judgements can be

reasonably distinguished to five grades. So we use

five-judge in this paper. The value corresponding to

each level is shown in table 1.

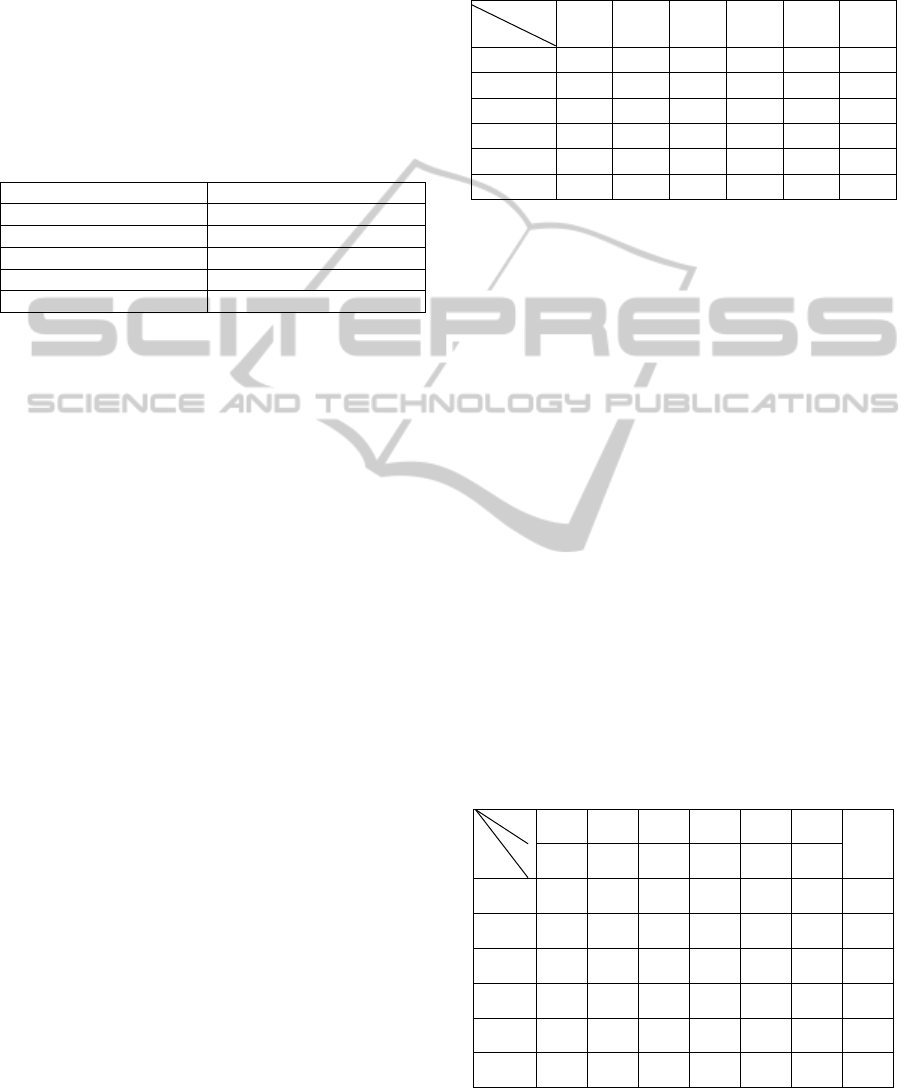

Table 1: Corresponding value of five-judge.

Grade Value

Very high 10

High 8

General 6

Low 4

Very low 2

In order to unify the indicator, transform the

indicators which “the more, the better” into “the less,

the better” indicators. So define the three “the more,

the better” indicators evaluation score is the opposite

number of their value. Setting different P

i can

highlight the indicators which the buyer is more

concerned about. The more important the indicator

to the buyer, the higher the weight of E

i i.e., Pi is.

Choose the right suppliers:

First normalize the evaluation score a

ij, let aij’ be

the normalized score of E

i,

ij

’ ∈ [−1,1]

, then compute

each supplier’s expectancy evaluation:

p

j

a′

ij

, i = 1,2,…, n

j

(1)

Then choose the minimum one from these

expectancy evaluations, the corresponded supplier is

the best supplier for buyer.

min

i

p

j

a′

ij

j

→S

k

∗

(2)

3.2 Numerical Example

In a manufacturing supply chain, one automobile

producer, namely A, is the core firm. In order to

mitigate supply risk, the firm A considers choosing 2

suppliers as its main supplier and second supplier

from six alternative suppliers.

S

1-S6 represents each of the six suppliers, and

E

1-E6 represent six indicators, i.e., probability of

supply risk, harmful levels of supply risk, financial

support, allowable time to deal with risks, number of

affected units, and risk management mechanism.

The data of all the six suppliers’ indicators is shown

in table 2.

Table 2: Data of suppliers’ indicators.

Ej

Si

E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6

S1 0.25 8 2.1 25 23 8

S2 0.1 8 1.8 20 9 4

S3 0.12 6 2.6 14 15 4

S4 0.18 10 2.8 17 12 8

S5 0.24 6 1.9 19 25 6

S6 0.16 8 1.5 12 7 4

The firm A firstly requests his main supplier

should have low probability of supply risk, and it is

better if the number of affected units could be fewer.

Then it cares about the harmful levels of supply risk,

allowable time to deal with risks, and the risk

management mechanism, and financial support is the

last one to be considered. For his second supplier,

firm A firstly requests the financial support should

be enough, second the harmful levels of supply risk

better be lower. The probability of supply risk, the

number of affected units, and the risk management

mechanism are on the third place. The harmful

levels of supply risk are considered last.

Based on the firm A’s requirements of supply,

evaluate P

i. For the main supplier: let Pi be 0.25,

0.15, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, and 0.15. For the second

supplier: let P

i be 0.15, 0.10, 0.25, 0.20, 0.15, and

0.15.

The decision matrix is showed in table 3 and

table 4.

Choose the minimum one from the last row of

the two decision matrixes, the corresponded supplier

is the most suitable supplier for buyer.

Table 3: Decision matrix of the main supplier.

Ei

Pi

Si

E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6

∑

0.25 0.15 0.10 0.15 0.25 0.15

S1

0.24 0.17 -0.17 -0.23 0.25 -0.24 0.06

S2

0.10 0.17 -0.14 -0.19 0.10 -0.12 0.01

S3

0.11 0.13 -0.20 -0.13 0.16 -0.12 0.03

S4

0.17 0.22 -0.22 -0.16 0.13 -0.24 0.03

S5

0.23 0.13 -0.15 -0.18 0.27 -0.18 0.08

S6

0.15 0.17 -0.12 -0.11 0.08 -0.12 0.04

MITIGATE SUPPLY RISK IN SUPPLY CHAIN

547

Table 4: Decision matrix of the second supplier.

Ei

Pi

Si

E1 E2 E3 E4 E5 E6

∑

0.15 0.10 0.25 0.20 0.15 0.15

S1 0.24 0.17 -0.17 -0.23 0.25 -0.24 -0.03

S2 0.10 0.17 -0.14 -0.19 0.10 -0.12 -0.04

S3 0.11 0.13 -0.20 -0.13 0.16 -0.12 -0.04

S4 0.17 0.22 -0.22 -0.16 0.13 -0.24 -0.05

S5 0.23 0.13 -0.15 -0.18 0.27 -0.18 -0.01

S6 0.15 0.17 -0.12 -0.11 0.08 -0.12 -0.02

In this example, firm A should choose the fourth

supplier S

2 as its main supplier, and the fifth supplier

S

4 as its second supplier.

If a firm considered more factors when it chooses

suppliers, such as distance, methods and price of

transportation, exchange rate fluctuations, changes

in demand and raw materials cost, etc, these factors

can be transformed to special risk indicators, and use

this model to choose the suitable suppliers.

4 CONCLUSIONS

As one of the most important part of supply chain,

supply disruption may bring great loss to the

enterprise and the whole supply chain, even break

down the whole supply chain. This paper analyses

the composition of supply risk, and methods to

mitigate supply risk, addresses dual-supplier or

multi-supplier supply model may be an effective

method. In order to choose suppliers for the whole

supply chain, a mathematical model is developed

and verified by a numerical example.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our thanks go to everyone who supported our work,

and who provided us lots of material. We also thank

the team members from the company who sponsored

this work, whose support is greatly appreciated.

REFERENCES

Jian Li, Shouyang Wang, T. C. E. Cheng, 2010,

Competition and cooperation in a single-retailer

two-supplier supply chain with supply disruption, Int.

J. Production Economics 124, 137–150.

Scott C. Ellis, Raymond M. Henry, Jeff Shockley, 2009,

Buyer perceptions of supply disruption risk: A

behavioural view and empirical assessment, Journal of

Operations Management 28, 34-36.

Xueipng Li, Yuerong Chen, 2009, Impacts of supply

disruptions and customer differentiation on a

partial-backordering inventory system, Simulation

Modelling Practice and Theory 18, 547–557.

Zhang Yi-bin,Chen J un-fang, 2007, A Framework of

Identifying Supply Chain Risks and Their Flexible

Mitigating Polices, Industrial Engineering and

Management, 47-52.

Chen Chang-bin, Miu Li-xin, 2009, An Analysis of

Supply — chain Classification , vulnerability and

Management Method, business economy, 98-101.

Li Leiming, Liu Bingquan, 2010, Research Review of the

Management Research of the Supply Chain Disruption

Risk, Science and Technology Management Research,

236-239.

Lou Shan-zu0,Wu Yao-hua,Lu Wen,Xiao Ji-wei, 2010,

Optimal inventory management under stochastic

disruption, Systems Engineering — Theory &

Practice,469-475.

R. Eglin, 2003, Can suppliers bring down your firm?

Sunday Times (London), appointments sec., p. 6.

Oke, A., Gopalakrishnana, M., 2009, Managing

disruptions in supply chains: a case study of a retail

supply chain. International Journal of Production

Economics 118 (1), 168–174.

Craighead, C. W., Blackhurst, J., Rungtusanatham, M. J.,

Handfield, R. B., 2007, The severity of supply chain

disruptions: design characteristics and mitigation

capabilities. Decision Sciences 38 (1), 131–156.

S. Chopra, M. Sodhi, 2004, Managing risk to avoid

supply-chain breakdown, MIT Sloan Management

Review 46 (1) 53–61.

Sheffi, Y., Rice Jr., J., 2005, A supply chain view of the

resilient enterprise. MIT Sloan Management Review

47 (1), 41–48.

Hendricks, K. B., Singhal, V. R., 2003, The effect of

supply chain glitches on shareholder wealth. Journal of

Operations Management 21 (5), 501–522.

Tomlin, B., 2005, Selecting a disruption-management

strategy for short life-cycle products: diversification,

contingent sourcing, and demand management

Working Paper, Kenan-Flagler Business School,

University of North Carolina.

Tomlin, B., 2006, On the value of mitigation and

contingency strategies for managing supply-chain

disruption risks. Management Science 52, 639–657.

Lariviere, M. A., Porteus, E. L., 2001, Selling to a

newsvendor: an analysis of price-only contracts.

Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 3,

293–305.

Wang, Y., Gerchak, Y., 2003. Capacity games in assembly

systems with uncertain demand. Manufacturing &

Service Operations Management 5, 252–267.

Tomlin, B., 2003. Capacity investment in supply chains:

sharing the gain rather than sharing the pain.

Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 5,

317–333.

ICEIS 2011 - 13th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems

548

Bernstein, F., DeCroix, G. A., 2004, Decentralized pricing

and capacity decisions in a multitier system with

modular assembly. Management Science 50,

1293–1308.

Cachon, G., Lariviere, M., 2001, Contracting to assure

supply: how to share demand forecasts in a supply

chain. Management Science 47, 629–646.

MITIGATE SUPPLY RISK IN SUPPLY CHAIN

549