KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL

PERFORMANCE - A KM IMPLEMENTATION

FRAMEWORK IN INDIAN CONTEXT

Himanshu Joshi

and Deepak Chawla

International Management Institute, B-10, Qutab Institutional Area, Tara Crescent, 110016, New Delhi, India

Keywords: Knowledge management, Strategy, Assessment, Framework, Performance, India.

Abstract: Knowledge Management (KM) is much more than just dissemination of knowledge. The real challenge

organizations and decision makers face is conceptualizing the right approach to implement KM and

developing strategies to manage the entire knowledge value chain. The purpose of this paper is to determine

the state of KM implementation in Indian organizations. Literature survey, focus group discussion (FGD)

and personal interviews are used for data collection. This paper reviews the existing KM frameworks and

attempts to identify key dimensions. The sample comprised of Indian organizations which have either

implemented KM or initiated the process of KM in their organizations. Convenience sampling is used to

select the respondents. Transcripts prepared from FGD and personal interviews are subjected to content

analysis. The paper reports the perceptions, views and experiences of senior executives. An attempt has

been made to integrate the data collected into a framework to facilitate KM implementation. Although a

number of empirical studies have been conducted in the past to study KM impact on performance, not many

qualitative studies exist. The findings can help organizations to leverage knowledge in a structured manner

to improve performance.

1 INTRODUCTION

The 21

st

century knowledge economy is

characterized by profound changes and

transformation related to nature of work,

employment, skill sets and the way business is

conducted. Developing trends like pervasive

computing, mass customization, continuous

learning, globalized competition, collaborating

partnering and virtual enterprise define the nature of

knowledge driven economy (Holsapple and Jones,

2004). Further rising expectations of customers,

suppliers and investors; emergence of global

workforce; availability of opportunities and attrition

rate also contribute to changes in the marketplace.

To ensure consistent differentiation and competitive

advantage, there is a greater emphasis being given to

exploitation of knowledge resource.

Knowledge and its importance to economy is

nothing new, however, the degree of reliance on

knowledge driven strategies to generate value in the

economic system is increasing. The last two decades

have witnessed a growth in computing power along

with reduction in cost of computing and

communications. This IT revolution in the form of

digital technologies and open system standards have

made it possible to store, process, manipulate and

transmit large quantities of information at low costs.

In India, knowledge driven economy is

considered to include primarily high-technology or

information and communication technology (ICT)

industries. But the time is opportune for it to use the

concept more broadly to include all stakeholders and

industries which use existing and new knowledge to

improve their productivity and overall performance.

India with its large consumer base, English speaking

knowledge workforce, active private sector,

developed financial sector and robust science &

technology infrastructure makes it best suited to

harness its strengths to enhance its economic

performance along with boosting social welfare.

Successful KM implementations are those that

rely on sharing of knowledge for competitiveness

and growth. A number of empirical studies exist

which investigate and explain the relationship

between management of knowledge and

competitiveness. Competiveness is a broad theme

136

Joshi H. and Chawla D..

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE - A KM IMPLEMENTATION FRAMEWORK IN INDIAN CONTEXT.

DOI: 10.5220/0003626801360145

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2011), pages 136-145

ISBN: 978-989-8425-81-2

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

defined by the ability of an individual or an

organization to mobilize and manage its resources

for enhancing performance. A study conducted by

KPMG on 423 organizations from UK, Europe and

US, reports that organizations surveyed had an

understanding of the potential role KM could play

and expected significant benefits in the form of

improving competitive advantage, marketing,

customer focus, employee development, product

innovation and profit growth – providing real

benefits like improved decision making, faster

response rate and better delivery of customer service

(Knowledge Management Research Report 2000).

Similarly, in a study conducted by Griffith

University and BML Consulting in Indian context,

respondents expected revenue growth, competitive

advantage and overall employee development as

long term benefits. Short term benefits perceived

were reducing cost, improving marketing and

enhanced customer focus (Knowledge Management

Research Report, 2002). In another study conducted

by The Economist Intelligence Unit (2007), sharing

of best practices, better response to customer

demands, innovative product development, better

usage of intellectual property, better collaboration

with external partners, improved decision making,

greater visibility across value chain and greater

likelihood of developing new intellectual property

were cited as the main benefits of KM. Davenport et

al. (1998) identified likely success factors leading to

KM project success. The major factors are linking to

economic performance or industry value, technical

and organizational infrastructure, standard flexible

knowledge structure, knowledge friendly culture,

clear purpose and language, change in motivational

practices, multiple channels for knowledge transfer

and senior management support. Although, there are

a number of empirical studies that substantiate on

KM planning and implementation process, key

enablers and performance dimensions, little support

is found in the literature for a qualitative study based

implementation framework in Indian context.

The objective is to conduct an exploratory

qualitative study through literature survey and taking

to KM experts from Indian organizations to gather

evidences on the process of KM implementation and

its impact on performance. To achieve that, various

KM implementation frameworks have been

discussed and a comparison of its dimensions carried

out. Finally, the paper presents a practical

framework for organizations to facilitate the KM

journey.

In order to systematically derive value of

knowledge, it’s essential to formalize and structure

the initiative. A good way of doing this is in the

form of a conceptual framework which guides and

facilitates the planning and implementation of

initiatives. According to Wong and Aspinwall

(2004), developing a KM implementation

framework should be the first stage of any KM

initiative as it guides the implementation process and

improve the chances of successfully incorporating

the same in an organization.

The paper is organized as follows: review of

literature is discussed next. This is followed by

methodology used in the research study. The fourth

section presents the analysis of data followed by

results. The final section discusses the conclusion,

limitations and directions for future research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

According to Wong and Aspinwall (2004), an

important reason why many organizations are still

struggling with KM and failing to realize its full

potential is that they lack the support of a strong

theoretical foundation to guide them in its

implementation. Managing knowledge in

organizations requires managing several processes

of knowledge such as initiation, implementation,

ramp-up and integration (Szulanski, 1996);

generation (acquisition; dedicating resources; fusion;

adaptation; and building knowledge networks),

codification and transfer (Davenport and Prusak,

1998); acquisition, conversion, application and

protection (Gold et al., 2001); acquisition, selection,

generalization, assimilation and emission (Holsapple

and Jones, 2004); creation, transfer, integration and

leverage (Tanriverdi, 2005), creation, storage,

sharing and evaluation (Gumus, 2007); generation,

codification, transfer and application (Singh and

Soltani, 2010).

Holsapple and Jones (2004) have defined

knowledge chain model to understand the linkage

between KM and organizational performance. The

model presents nine distinct, generic classes of

activities, five primary and four secondary

(measurement, control, coordination and leadership)

that an organization performs in the course of

managing its knowledge resources. Tanriverdi

(2005) identified four interrelated processes which

form a part of three KM capabilities defined as

product KM capability, customer KM capability and

managerial KM capability.

According to O’Dell et al. (2004), APQC has

studied KM implementation in organizations they

have worked with and developed APQC roadmap to

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE - A KM IMPLEMENTATION

FRAMEWORK IN INDIAN CONTEXT

137

KM. It includes five stages common to successful

KM implementations, viz. getting started, explore &

experiment, pilot and KM initiatives, expand &

support and institutionalize KM. Apart from that,

culture, buy-in, measurement and creating a business

case for KM are themes that transcend the stages.

Gold et al. (2001) suggest that a knowledge

infrastructure consisting of technology, structure and

culture along with a knowledge process consisting of

are essential preconditions for effective KM.

Some of the earlier research studies, for e.g.

Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) emphasized on the

importance of knowledge-creation and have tried to

explain the interplay between tacit and explicit

knowledge in the form of a generic model to

demonstrate knowledge-creation. Further Soo et al.

(2002) look at knowledge-creation process

comprising of sourcing of information, internalizing,

integrating and applying it. The source of

information can either be from formal/informal

networking and internal/external acquisition. Next,

organizations must have absorptive capacity to

internalize and integrate it. Finally, it must be

applied to improve quality of problem

solving/decision making resulting in knowledge

based outcomes, i.e., innovation and better business

performance.

Wiig (1993) has proposed a KM framework

which comprises of three pillars (survey, analyze

and categorize knowledge; appraise and evaluate

knowledge; and synthesize knowledge) to explain

the process of knowledge creation, manifestations,

use and transfer. Similarly, Arthur Anderson and

APQC have proposed a KM process comprising of

seven activities (share, create, identify, collect,

adapt, organize and apply) and four enablers

(leadership, culture, technology and measurement)

that facilitate the development of organizational

knowledge through the KM process (Jager, 1999).

Leonard-Barton (1995) has proposed a framework

which revolves around the concept of core capability

comprising of managerial activities and systems

which offer competitive advantage. These core

competencies can be created if the focus is on

knowledge-building activities – shared problem

solving, importing and absorbing technological and

market knowledge, experimenting and prototyping,

and implementing and integrating new

methodologies and tools. Demarest (1997) has

attempted to model knowledge economies within the

firm by focusing along four processes, viz.,

construction, embodiment, dissemination and use.

Construction is the process of discovering or

structuring knowledge, embodiment is selecting a

container for created knowledge; dissemination

refers to human processes and technical

infrastructure required for make it available within

the firm; and use is the application of knowledge to

generate customer value.

Bukowitz and Williams (1999) have developed

Knowledge Management Diagnostic (KMD) based

on a model known as Knowledge Management

Process Framework, which consist of seven KM

activities (get, use, learn, contribute, access,

build/sustain, divest). They distinguish two

processes in KM, i.e., tactical (triggered by market-

driven opportunities) and strategic (triggered by

macro-environment factors) with focus on the use of

knowledge based assets to respond to these triggers.

Maier and Moseley (2003) have looked at KM

implementation involving five dimensions:

identification and creation; collection and capture;

storage and organization; sharing and distribution;

and application and use.

The starting point of any KM initiative is

instilling a belief that there are certain business

problems which can be addressed by effective

management of knowledge. Holsapple and Joshi

(2004) believe that organizations are places for

episodes which are triggered by knowledge need

(opportunity) and culminates with the satisfaction of

that need (or abandonment). These knowledge

management episodes (KME) create value for the

organization in the form of learning and projection

which in turn form the basis for innovation.

An examination of the various frameworks and

approaches to KM implementation reveals that past

efforts have focused on implementing KM with

inadequate reference to how it’s going to impact the

performance. It is only recently, however, that

organizations have started discussing linking KM

activities with measurable business results. Any

model or framework is of little use without an

understanding of how the activities can be

operationalized to be geared for enhancing business

performance. Therefore, there is a need to

systematically examine the elusive link between KM

and its impact on business performance.

2.1 KM and Performance

Some evidences of improved performance through

KM can be seen in organizations which have a

formal KM initiative in place. But, linking KM

practices to business results and competiveness is

not easy and there are disparate views among

researchers. Hiebler (1996) believes that

organizations that are able to create and use a set of

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

138

measures tied to financial results seem to come out

ahead in the long run. According to Wolford and

Kwiecien (2004), the frequently asked question is,

how can you put a value to knowledge? KM

initiatives must show a return otherwise the effort

goes waste. Soo et al. (2002) feel that although

knowledge is difficult to measure, it does have a

clear impact on outcome. There are a good number

of proxies that can be used to measure KM, e.g.,

measuring certain firm processes (i.e., problem

solving and decision making) or outcomes (i.e.,

innovative outputs).

A number of organizations have developed

indicators to measure and evaluate the impact of KM

initiative on business performance. Saunders (2007)

believes that it’s important to define KM value

proposition in the very beginning. Most KM efforts

are primarily aimed at increasing customer intimacy,

faster time to market or operational excellence.

Holsapple and Singh (2004) have provided

evidences on how KM practices can manifest itself

from the following standpoints: improving

productivity (e.g. lower cost, greater speed), enhance

reputation (e.g. better quality, dependability, brand

differentiation), enhancing organizational agility

(e.g. greater flexibility, rapid responsiveness, change

proficiency), and fostering innovation (e.g. new

knowledge products, services, processes).

Tanriverdi (2005) used Tobin’s Q and Return on

Assets (ROA) to measure market-based firm

performance. Tobin's Q is the ratio of the market

value of a firm's assets to the replacement cost of the

firm's assets. Zack et al. (2009) found KM practices

to be directly related to organizational performance

which, in turn, was directly related to financial

performance. However, no direct relationship was

found between KM practices and financial

performance. Similarly, Gold et al. (2001) have

associated KM capabilities with organizational

effectiveness as a key aspect of performance. They

feel that capturing the contribution of knowledge

capabilities in terms of bottom line (Return of

investment (ROI), ROE etc.) may be confounded by

other uncontrollable business, economic and

environmental factors. They have measured

effectiveness through various non-financial items

like ability to innovate, coordination of efforts,

commercialization of new products, ability to

anticipate surprises, responsiveness to market

change, reduced redundancy to information or

knowledge. According to Lee and Choi (2003), in

order to achieve a better understanding of KM

performance, companies should attempt to link KM

processes with intermediate outcomes. They have

identified organizational creativity as an important

intermediate outcome to organizational effectiveness

and survival. It is this creativity that transforms

knowledge into business value. However, Hariharan

(2002) feels that to keep KM implementation

oriented and business focused, its important to have

a combination of lagging (actual business outcomes)

and leading (performance drivers that would lead to

business outcomes) measures should be used.

3 METHODOLOGY

The method used to conduct the study involved four

steps. To start with, an extensive literature review

was carried out to understand the KM

implementation models and frameworks developed

by researchers. This was followed by a focus group

discussion (FGD) and personal interview. FGD is a

qualitative research technique best suited to get the

true representation of participant’s feelings and

beliefs. The questions used were open-ended,

designed to gather perception, beliefs and ideas

around experiences from KM implementation.

Personal interviews were used to get an in-depth

understanding about participant’s experiences

around KM. Finally, a comprehensive list of KM

planning and implementation activities was

identified from the data collected.

The sample comprised of KM practitioners,

mainly senior executives (CEO, Vice President,

General Managers – IT, Directors, etc.) who have

experienced KM implementation in their current or

in previous organizations. One aspect of

homogeneity in the sample was the fact that

respondents had either led or been involved with

KM implementation in their organizations.

Respondent diversity was maintained by recruiting

them from various private sector industries, age

group and work experience. This was done in order

to get all possible insights into the attitude,

perception and beliefs held by KM practitioners. The

age of the respondents ranged from 32-60 years. On

an average the working experience of the

participants was around 15 years. Respondents were

primary from Manufacturing, IT/ IT enabled

services, consumer durables, insurance,

telecommunications and publishing industry.

Convenience sampling scheme was used.

For FGD, 30 emails were sent to prospective

participants and subsequent follow-ups over email

and phone resulted in 10 agreeing to participate but

2 dropped out due to some urgent work

commitments. A discussion guide was prepared

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE - A KM IMPLEMENTATION

FRAMEWORK IN INDIAN CONTEXT

139

before the FGD to ensure that the sequencing of

questions and issues discussed facilitate conducting

the session in a logical manner. Similarly, 20

respondents operating in Delhi and surrounding

areas were contacted, out of which 10 agreed for a

personal interview. The interviews were conducted

in an unstructured, open and discussion oriented

manner to encourage interviewees to share their

experiences, opinions and insights on the KM

journey.

The questions included in the discussion guide

and interview template covered various aspects

related to KM planning and implementation like the

need for KM, its objectives, alignment with business

strategy, resource requirements, execution, business

impact and measurement. The proceedings of the

FGD and interviews were audio/video recorded and

transcribed into documents which was subjected to

content analysis. The analysis is discussed in the

next section.

4 ANALYSIS OF DATA

As mentioned earlier, each respondent shared their

views on how KM was being implemented in their

organization. Majority of respondents felt that KM is

important, although divergent views emerged on the

approach to be used for KM implementation. Based

on the content analysis, five dimensions were

identified which form a part of the KM

implementation process being used by organizations.

They are plan, design, implement, evaluate and

accelerate. These five dimensions have been selected

because they were considered salient by

respondents. Further, they also appeared in

approaches and frameworks discussed by previous

researchers.

Plan: Respondents felt that exhaustive planning

is crucial to determine the value derived out of KM

initiatives. Since most of the initiatives are

unstructured or informal, planning an approach to

KM implementation is the first step. But, the

unstructured approach is leaving too much to chance

because a lot of information is shared through the

grapevine. The real issue is “Is it important to

structure or formalize it, so that it becomes part of

strategy?” Therefore, if KM is made a part of overall

vision, it has a chance of influencing strategic

decision. Respondents also felt that putting it as part

of the vision statement makes implementation

simpler. It’s important to specify the goals and

objectives of KM system in the beginning.

According to Saroch and Barmash (2007), a key

success factor for a KM system is to plan it around a

specific, critical issue in the company.

Planning involves conceptualizing a systematic

representation of various KM stages, processes,

activities within each stage, resource requirements

and output derived. It entails first figuring out what

knowledge a company possesses and devising

strategies to share it with other people who can use it

to create new products and services or improve

existing processes. It’s important to ask yourself

relevant questions during the planning stage itself to

get clarity on KM implementation strategy. Some

key questions which may be important during

planning stage are summarized in table 1 below:

Table 1: KM Planning Activities.

Plan Issues

Literature

Support

KM

Objectives

Need for KM;

identification of business

problems; anything we

already do which could

be related to KM;

relevant resources

(human, technological,

financial); who will be

involved

Szulanski

(1996);

Maier and

Moseley

(2003);

Holsapple

and Jones

(2004);

O’Dell et al.

(2004);

Saroch and

Barmash

(2007)

Business

Objectives

Define KM; How KM fits

into the overall vision

Top

Management

Buy-In

100% commitment

Design: It’s important to identify a process to

deploy KM. A big-bang approach may kill the

initiative in the initial stages itself. Top management

buy-in at this stage is crucial to secure additional

funding for full scale development and deployment.

If possible identify an organization which has

implemented KM. Talking to people from other

companies who have already achieved KM maturity

is must to benefit from their experience and to avoid

early pitfalls. Respondents were of the view that

organizations should establish a set of key

performance indicators (KPIs) to assess

organizational performance in implementing KM.

Minonne and Turner (2009) believe that choosing

the right KPIs is critical to success. Every KPI,

whether it is used to clarify the current position,

guide the implementation of KM strategy or track

changes in the image of the future, will affect

actions and decisions. According to Hanley and

Malafsky (2009), the measurement process is

composed of several steps to clearly identify what

should be measured, how to measure it and how to

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

140

use the measures.

Table 2: KM Design Activities.

Plan Issues

Literature

Support

Business

Case

Select a process; learn

from KM implementers;

Define team composition,

structure and

accountability; KM

technology; KM budget;

duration of the pilot

Leonard-

Barton

(1995);

O’Dell et al.

(2004);

Minonne and

Turner

(2009);

Hanley and

Malafsky

(2009)

Define

Measures

Identify KPIs; how to

measure; how to analyze

Implement: The adoption of KM best practices

becomes easier if benefits associated with it can be

demonstrated early. A case study is good approach

to initiate a pilot. Involvement of KM practitioners

in the team to plan for right kind of pilot is crucial.

Respondents were of the view that the biggest issue

faced by KM practitioners is capturing tacit

knowledge for organizational benefit. Nonaka

(1991) suggests socialization as a way through

which our mental models, belief systems, value

systems and the way we do things gets transferred.

Respondents felt that it’s important to make

arrangements for socialization so as to make

personal knowledge organizational knowledge. It

could be in simple ways like coffee table talk, recess

breaks etc. Socialization can also happen when a

person in a domain works with peers or people from

different department come together as part of Cross

Functional Team (CFT).

Table 3: KM Implementation Activities.

Plan Issues Literature

Support

KM

Pilot

Build Communities of

Practice; Use IT tools

Nonaka

and

Takeuchi

(1995);

Leonard-

Barton

(1995);

O’Dell et

al. (2004)

KM

Strategy

Mandatory Replication

(Push); reward & recognition

(pull)

Success

Stories

Documentation of

improvements; sharing best

practices; build evidence by

showing leadership small

gains

A lot has been talked about KM strategy.

Initially it’s important to pull people towards the

initiative by creating awareness about the overall

objective and benefits. Push would mean making

people follow formal documented written down

processes. The push strategy works well to ensure

compliance to integrate the best practices in all

workflows. “Simply follow the process as given in

the KM platform”, would help in ensuring

consistency and minimize deviations.

Evaluate: A number of organizations have

developed indicators to measure and evaluate the

impact of KM initiative on business performance.

Evolve KM metrics along the journey. It’s important

to plan for measurements in the very beginning to

track progress and take corrective measures.

Organization should develop ways to determine how

KM initiative is impacting human behaviours and

bottom line. Hanley and Malafsky (2009) believe

that KM initiative measurement should include both

quantitative and qualitative measures as latter

augments the former with additional context and

meaning. Quantitative measures provide hard data to

evaluate performance between points or to spot

trends whereas, qualitative measures use the

situation’s context to provide a sense of value

(stories, anecdotes and future scenarios).

Table 4: KM Evaluation Activities.

Evaluate Issues Literature Support

Formal

Measure

-ment

Behavioral,

Quantitative,

Financial/

Non-

financial

Wiig (1993); Arthur

Anderson and APQC

(1996); Bukowitz and

Williams (1999); Hariharan

(2002); Lee and Choi

(2003); Holsapple and

Jones (2004); Tanriverdi

(2005); Gumus (2007);

Zack et al. (2009);

Hanley and Malafsky(2009)

Accelerate: To ensure the sustainability of KM

initiative, it’s important to identify business

processes within and outside the organizations

where the best practices can be replicated. It is

important that key people are identified across

locations who could own the initiative. According to

O’Dell (2004), there are two approaches to

expansion. One is to apply criteria for pilot selection

of other units or to develop an all-at-once strategy.

To augment capabilities globally, it’s important to

leverage internal skills, hire people from outside,

refine existing roles and create new roles.

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE - A KM IMPLEMENTATION

FRAMEWORK IN INDIAN CONTEXT

141

Table 5: KM Acceleration Activities.

Accelerate Issues

Literature

Support

Cultivate and

Expand

Identify new

processes where

KM will work;

identify support

teams; make KM

integral to people

KRA’s and

performance

appraisal

Szulanski (1996),

Bukowitz and

Williams (1999),

O’Dell et al.

(2004), Holsapple

and Jones (2004),

Tanriverdi (2005)

Communicate

Business results

and success stories

4.1 KM Enablers

The following dimensions have been discussed in

the literature and also considered extremely

important by respondents during the FGD and

personal interviews. Arthur Anderson and APQC

propose that four enablers (leadership, culture,

technology and measurement) can be used to foster

the development of organisational knowledge

through the knowledge management process (Jager,

1999). Lee and Choi (2003) consider organizational

culture, structure, people and IT as most important

to successful KM.

Leadership: The commitment for the top

management is a must. Leadership influences the

organizational ability to deal with knowledge related

issues. Chawla and Joshi (2010) believe that

leadership plays a crucial role in creating,

developing, and managing the organizational

capabilities by creating effective teams within a

diverse workforce; tap talent throughout the

organization by recruiting, retaining, and developing

people at all levels; build and integrate cultures as

mergers and acquisitions become common; use IT to

enable and integrate KM processes; and develop

rewards and recognition systems.

Technology: The success of KM initiatives depends

on the appropriateness of technological tools used.

However, KM is broader concept with technology as

a process enabler. Always adopt IT tools which are

relevant to your KM initiative.

Culture: For KM people should be empowered to

take and own up decisions and not always follow a

hierarchy. It’s important to celebrate success of

others. KM brings about a change in the culture of

the organization.

Structure: In all probability KM mandates a loose

structure. Creating a KM office with a leader having

some 10-15 odd people under him doing KM may

not work. All people should be engaged in hearts

and mind by constantly showing benefits of the

programme and addressing the question “What is it

in for me”.

4.2 Business Impact and Performance

Majority of respondents felt that KM relationship

with time and cost could explain its impact. Other

factors could be ROI, customer, supplier and

employee satisfaction index etc. Most respondents

were of the view that if tangible benefit measures

could be developed around KM, the justification for

implementation becomes simpler. To put it simply,

what gets measured gets accepted and implemented.

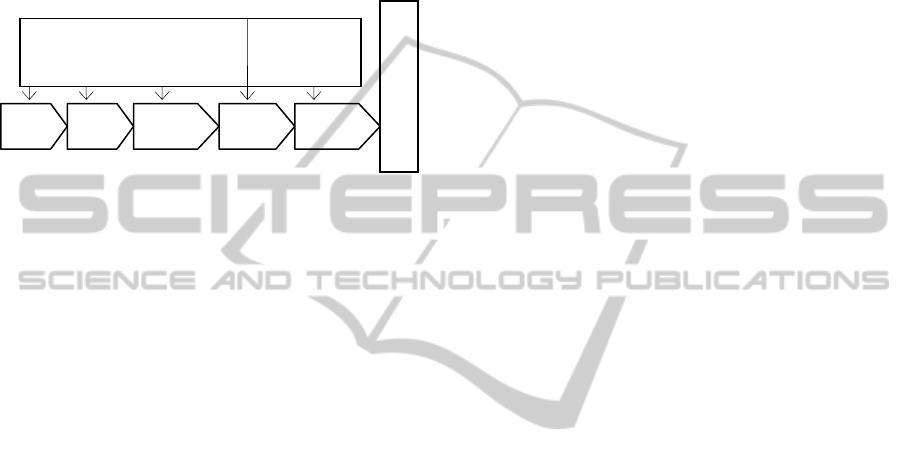

The results are integrated in the form of a KM

framework (see Figure 1) which is discussed next.

5 RESULTS

Based on analysis of data collected from review of

literature and insights derived from FGD and

personal interviews, we propose a framework for

KM planning and implementation. The idea is to

demonstrate how the various stages, activities and

resources contribute to achieving KM objectives and

business benefits.

In addition to the KM activities, a number of

KM enablers have been incorporated into the KM

framework. Organizational leadership, culture,

structure and technology have been researched in

detail and advocated by many researchers. Lee and

Choi (2003) believe that KM enablers may be

structured based upon a socio-technical theory. It is

important to provide a balanced view between a

technological and social approach to KM. Therefore,

KM should always be viewed as a system that

comprises of a technological subsystem as well as a

social one (Wong and Aspinwall, 2004). Just taking

it as an IT initiative can be problematic as most

technologically oriented initiatives have failed to

meet expected business results. Saroch and Barmash

(2007) learnt that the biggest challenge to KM is

getting support, commitment, and a separate budget

from top management. Chong (2006) found in

Malaysian ICT companies that if nature of the

business is knowledge-intensive which involves

employees working in teams; and therefore

leadership plays an important role in empowering

employees to take decisions. Singh and Soltani

(2010) found that in Indian IT organizations the

involvement of top management in allocating the

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

142

necessary resource towards sustaining KM

initiatives require attention. Similarly, Anantatmula

and Kanungo (2010) found top management support

is most crucial to build a successful KM initiative as

it ensures strategic focus. KM is a people driven

initiative and therefore utmost care is needed to

promote social enablers. In our framework

organizational leadership, culture and structure are

social enablers, while IT is a technical enabler.

Figure 1: KM Planning and Implementation (KMPI)

Framework.

This framework will help organizations to gauge

the organizational position in the KM journey,

develop an understanding of the various challenges,

techniques to overcome the same and making it an

enterprise level initiative. The above results are

elaborated through a case study. We believe that this

evidence will offer decision makers an opportunity

to evaluate real world situations and get an

appreciation for successful KM initiative.

5.1 Case Study: Managing Knowledge

at Bharti Airtel

Bharti Airtel Limited is a leading telecommunication

services provider with operations in 18 countries

across Asia and Africa. With increasing employee

and customer base, the company witnessed

challenges associated with keeping consistent

business practices across locations. KM initiative at

Bharti started in 2003, and since then it has come a

long way. The initiative started with Delhi circle and

slowly expanded into other circles. Roll out of

services all over India posed newer challenges for

decision makers. Each circle was using different

practices, process and policies related to business

operations. The real challenge was to bring in

consistency across locations and this was the starting

point for KM at Bharti. The broader KM objectives

were standardization of business processes;

minimize variation; use of available knowledge to

improve decision making; faster time to market and

generation of fresh ideas and innovation.

As Head, Operational Excellence and Quality

noted, “We picked some important key performance

indicators (KPIs) and started looking at variations

across locations. The variations were found to be

large. Next, we picked up locations which were

doing well on the KPIs and tried to identify the best

practices adopted. These best practices were shared

across locations to be replicated. The variations

started coming down.”

Recognizing that an organization the size of

Bharti could not achieve this without the power of

information technology (IT), efforts were made to

develop a system to share best practices. The portal

Insights@Airtel was to be used for sharing

knowledge and experiences. To encourage people to

share, the company also initiated an incentive

scheme where knowledge dollars (K$) were given to

people for sharing as well as replication of best

practices.

But technological platform and monetary

benefits were not enough to make KM happen. To

ensure and sustain quality of best practices, an

improvement was planned. For practices that were

found deemed fit for replication by subject matter

experts (SMEs) were considered for mandatory

replication. To facilitate this sharing and replication,

the company also started knowledge sharing session.

KM Process – The KM process at Bharti

primarily involves four stages, viz., identifying the

knowledge and source; creating a culture of

knowledge sharing and replication; using

information technology and tools to disseminate

knowledge and creating processes to leverage that

knowledge.

Push versus Pull – The key to KM success is

execution. For KM implementation, business

performance indices were linked with extent of best

practice sharing and replication. Through K$,

employees were encouraged to share and replicate

knowledge. Significant contributors are also invited

in various forums to share their experiences and

recognized and rewarded for their efforts. Apart

from K$, each location is given certain business

targets in terms of reducing variation across business

KPIs. Each employee in the organization has these

KPIs as part of key result areas (KRAs). A best

practice is for a particular KPI and therefore, savings

from best practice implementation is calculated. This

financial impact was approved by a finance officer.

Business Impact – KM initiative has helped

Bharti to retain employee knowledge in form of best

practices collected over the last seven eight years. It

has enabled the company in bringing new businesses

spread across geographies, to the KM platform.

Users who are new to the system can now search for

Leadership Culture Structure Technology

Social Enablers Technical Enablers

R

E

S

U

L

T

Plan Design Implement Evaluate Accelerate

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE - A KM IMPLEMENTATION

FRAMEWORK IN INDIAN CONTEXT

143

existing best practices and standardize the processes

according to them. So entire knowledge retained

over the last seven to eight years is extended and

replicated in turnaround time of 2 months. The key

to the success of this initiative has been in terms of

preventing reinventing the wheel, process variation

reduction across location and reduction in time taken

to align process as per best practices. Another reason

is rigorous documentation of practices. This has

resulted in consistent customer experience and

increased savings from best practice creation and

replication across locations.

6 CONCLUSIONS

A review of literature also reveals that since there

are many approaches and frameworks to KM

implementation, discretion of the implementer to

develop a common ground for KM implementation

is critical. The authors feel that although the

proposed KMPI model features most of the relevant

KM activities, there could be other environmental

and resource related dimensions that would

ultimately influence the conduct of KM initiative.

The authors suggest that the framework could be

extended to include other dimensions, which inhibit

or enable KM initiative. This may be required during

testing the applicability of the framework in

different business, industry and national contexts.

Our future research direction is to test the

applicability of the framework in various industries,

sectors, hierarchy levels etc. through survey data.

A limitation of the study is that analysis and

reporting of findings are based on the interpretation

of the researchers. Secondly, the framework is

proposed based on the inputs from Indian

organizations only, although attempt has been made

to incorporate findings from the existing body of

knowledge in the domain of KM. Hence, there is a

need to empirically investigate if any dimensions

have been incorrectly categorized or missed out.

The authors believe that a sound implementation

framework can help organizations with directions

and support to embark the KM journey. Rather than

simply saying that KM enhances performance, the

KMPI framework presents KM practitioners a

structured approach to realize the potential of KM.

However, developing such a framework may pose

challenges initially as they might not be aware of the

dimensions and its elements and their fitment within

the entire framework. Therefore, as KM

implementation is resource intensive involving high

stakes, it’s better to have a formal KM in place

rather than trying different things.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The paper is an outcome of a research initiative

sanctioned by the Department of IT, Ministry of

Communications and IT; Government of India

entitled “National Competitiveness in the

Knowledge Economy” to four institutions, viz. IIT-

M, IIT-R, IMI and NPC.

REFERENCES

Anantamula V. S. and Kanungo S. (2010), Modeling

Enablers for successful KM implementation, Journal

of Knowledge Management, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 100-113

Bukowitz, W. R. and Williams, R. L. (1999), The

Knowledge Management Fieldbook, Pearson

Education, London, Great Britain

Chawla, D. and Joshi, H. (2010) "Knowledge management

practices in Indian industries – a comparative study",

Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 14 No. 5,

pp.708 – 725

Chong, S. C. (2006), “KM Critical Success Factor”, The

Learning Organization, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 230-256

Davenport, T. H, DeLong, D. W, Beers, M. C (1998),

Successful knowledge management projects, Sloan

Management Review, Vol. 39 No.2, pp.43-57

Davenport, T. H., and Prusak, L. (1998), Working

Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They

Know, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School

Press

Demarest, M. (1997), "Understanding knowledge

management", Journal of Long Range Planning, Vol.

30, No.3, pp. 374-384

Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., Segars, A. H. (2001),

"Knowledge Management: an organizational

capabilities perspective", Journal of Management

Information Systems, Vol. 18 No.1, pp.185-214.

Gumus, M. (2007), The effect of communication on

knowledge sharing in organizations, Journal of

knowledge management practices, Vol. 8, No.2

Hanley, S. and Malafsky, G. (2004), A Guide for

Measuring the Value of KM Investments, Handbook

of Knowledge Management 2 – Knowledge Directions,

pp. 215-251

Hariharan, A. (2002), Knowledge Management: A

Strategic Tool, Journal of Knowledge Management

Practice, Vol. 3, No. 3; pp. 50-59

Hiebler, R. (1996), "Benchmarking Knowledge

Management", Strategy and Leadership, Vol. 24, No.2,

pp. 22-29.

Holsapple, C. W. and Singh, M. (2004), The Knowledge

Chain Model: Activities for Competiveness, Handbook

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

144

of Knowledge Management 2 – Knowledge Directions,

pp. 215-251

Holsapple, C. W. and Jones, K. (2004), Exploring Primary

Activities of the Knowledge Chain, Knowledge and

Process Management, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 155-174

Holsapple, C. W. and Joshi, K. D. (2004), A Knowledge

Management Ontology, Handbook of Knowledge

Management 1: Knowledge Matters, Springer Science

and Business Media, pp. 89-124

Jager D. M. (1999), The KMAT, Benchmarking

Knowledge Management, Library Management,

Volume 20, Number 7, pp. 367 – 372

Knowledge Management Research Report – India (2002),

Griffith University School of Management and BML

Consulting, available at http://www.knowledgepoint.

com.au/knowledge_management/Articles/KM-India-

2002.pdf (accessed April 03, 2008)

Knowledge Management Research Report (2000), KPMG

Consulting, available at http://www.providersedge.

com/docs/km_articles/KPMG_KM_Research_Report_

2000.pdf (accessed April 03, 2008)

Lee, H. and Choi., B. (2003), Knowledge Management

enablers, processes and organizational performance:

an integrative view and empirical examination”,

Journal of Management Information System, Vol. 20,

No. 1, pp. 179-228

Leonard-Burton, D. (1995), Wellsprings of Knowledge:

Building and Sustaining the Sources of Innovation,

Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

Maier, D. J. and Moseley, J. L. (2003), “The Knowledge

Management Assessment Tool (KMAT)”, The 2003

Annual: Volume 1, Training, John Wiley and Sons, USA

Minonne, C and Turner, G. (2009), “Evaluating

Knowledge Management Performance”, Electronic

Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 7 No. 5, pp.

583 - 592

O’Dell, C., Hasanali, F., Hubert, C., Lopez, K. Odem, P.

and Raybourn, C. (2004), Successful KM

Implementations: A Study of Best Practice

Organizations, Handbook of Knowledge Management

2 – Knowledge Directions, pp. 411-441

Nonaka, I. (1991), The Knowledge Cresting Company,

Harvard Business Review, Vol. 69, No. 6, pp. 96-104

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995), The Knowledge-

Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create

the Dynamics of Innovation, New York, NY: Oxford

University Press

Saroch R. and Barmash J. (2007), Architecting a

Knowledge Management System, Skyscrapr – An

online resource provided by Microsoft, available at

www.skyscrapr.net

Saunders, R. M. (2007), Managing Knowledge – How to

make money with what you know, Managing

Knowledge to Fuel Growth, Harvard Business School

Press, Boston, Massachusetts

Singh, A. and Soltani, E. (2010), “Knowledge

Management Practices in Indian Information

Technology Companies”, Total Quality Management,

Vol. 21, No.2, pp. 145-157

Soo, C., Devinney, T., Midgley, D. and Deering, A.

(2002), “Knowledge Management: Philosophy,

Processes, and Pitfalls”, California Management

Review, Vol. 44, No. 4, pp. 129-149

Szulanski, G. (1996), Exploring Internal Stickiness:

Impediments to the Transfer of Best Practices within

the firm, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17,

(Winter Special Issue), pp. 27-43

Tanriverdi, H. (2005), Information Technology

Relatedness, Knowledge Management Capability, and

Performance of Multibusiness Firms, MIS Quarterly,

Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 311-334

The Economist Intelligence Unit Report (2007), The

Economist, available at http://a330.g.akamai.net/7/

330/25828/20070628141731/graphics.eiu.com/upload

/portal/KNOWLEDGE_MANAGT_WEB.pdf (accessed

on October 16, 2008)

Wiig, K. M. (1993), Knowledge Management

Foundations, Thinking about Thinking: How people

and Organizations create and use Knowledge,

Arlington TX, Schema Press.

Wong, K. Y. and Aspinwall, E. (2004), Knowledge

Management Implementation Framework: A Review,

Knowledge and Process Management, Vol. 11, No. 2,

pp. 93-104

Wolford, D. and Kwiecien, S. (2004), Driving Knowledge

Management at Ford Motor Company, Handbook of

Knowledge Management 2 – Knowledge Directions,

pp. 501-510

Zack, M., McKeen, J. and Singh, S. (2009), Knowledge

Management ad Organizational Performance: An

Exploratory Analysis, Journal of Knowledge

Management, Vol. 13, No. 6, pp. 392-409

KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE - A KM IMPLEMENTATION

FRAMEWORK IN INDIAN CONTEXT

145