A USER CENTERED APPROACH FOR QUALITY ASSESSMENT

IN SOCIAL SYSTEMS

Nicolas Weber

1,2

and Stefanie N. Lindstaedt

1,2

1

Knowledge Management Institute, Graz University of Technology, Inffeldgasse 21a, Graz, Austria

2

Know-Center GmbH, Inffeldgasse 21a, Graz, Austria

Keywords: Information quality, Social information systems, Quality models.

Abstract: Analyzing the meaning of quality in information systems has a long tradition. As a result of the increasing

amount of user generated content on the web, addressing quality is more relevant than ever. Since

information is produced and consumed by different people in various contexts the perception of quality is

always closely tied to the users’ situation. This work proposes an approach for assessing quality in social

systems with respect to the users’ current needs.

1 INTRODUCTION

During last years the Web went through a

metamorphosis from a more or less static source of

information to a network of actively contributing

users. A new consciousness of web usage and new

technologies enabled the user to share knowledge on

the web. Systems that allow being author and

consumer at the same time are rapidly evolving.

Therefore, it is more and more important to check

and ensure information quality of the social

information system. Discovering a lack of quality is

the bottleneck in many social information systems

because provision of high-quality data is essential

for system acceptance (Ahn et al., 2007). The model

of information system success (Delone and McLean,

2003) names system quality and information quality

as crucial factors for system use and user

satisfaction.

Large social systems such as Wikipedia with

millions of entries overcome this problem by

arguing that having many pairs of eyes is the best

strategy for weeding out errors in wiki content. In

this way Wikipedia achieves a stupendous quality

for their articles (Giles, 2005). However, there are

only approximately 50 such large social systems on

the web while there are thousands of smaller social

systems dealing with a specific topic that cannot

make use of this strategy to ensure quality of the

web content. These systems are often denoted as the

long tail. Examples include corporate Wikis for

hard- and soft-ware products, forums and wikis

operated by communities of interest. Due to their

specific content, the community of users is smaller

and so there are less pairs of eyes for observing the

content quality. Systems that represent the long tail

are therefore more likely to face problems in dealing

with information quality. Information quality seems

to be a subjective concept for assessing an object;

hence quality cannot be generally measured.

This paper proposes a user centered approach for

quality assessment in social systems. Therefore three

questions are answered: First, how can we detect and

represent quality needs of the user? Second, how can

we measure the qualitative status of a resource?

Third, how can we map the resource quality status to

the user quality requirements in order to provide

resources that comply with the users´ quality needs?

2 MEASURING QUALITY

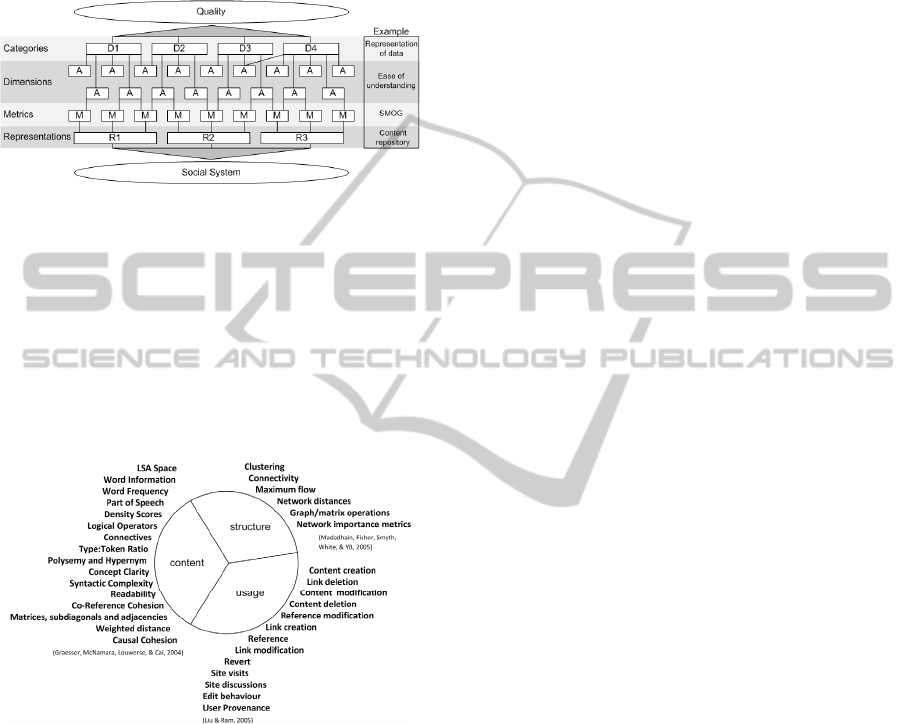

This section describes our approach for evaluating

the qualitative status of resources. Quality

assessment requires several levels of abstraction.

This approach proposes four levels of system

abstraction: Categories, Dimensions, Metrics,

Representations (see Figure 1). The approach of

Wang and Strong (1996) provides the technical

foundation of this model. Categories and

Dimensions are directly adopted. From the top-down

perspective the model provides a step by step

211

Weber N. and Lindstaedt S..

A USER CENTERED APPROACH FOR QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN SOCIAL SYSTEMS.

DOI: 10.5220/0003664502110216

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2011), pages 211-216

ISBN: 978-989-8425-81-2

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

specification of the concept quality; from the

bottom-up perspective the model provides an

abstraction from the system. The

specification/abstraction level of the quality

dimensions allows measuring them directly using a

set of metrics.

Figure 1: System abstraction layers for quality assessment.

Metrics are used to provide measures on a given

data set. Formal system representations provide a

computer readable basis for evaluating a system.

Representations provide different perspectives on an

information system and they are chosen depending

on the aspect of the system to be assessed; i.e. based

on content, structure or usage. Figure 2 shows

different possible system representations and

proposed metric categories for each representation.

Figure 2: System representations and metric categories.

A very common representation is structure based

representation in a directed graph. Several

approaches use graphs that represent relations

between objects. One example is social network

analysis (SNA) where a social system is represented

by nodes (people in the system) and edges

(relations/activities/events) to make a statement

about the whole system or individuals in the system

(Dom et al., 2003). Graph representations are not

only used for analysis of social networks; Jeon et al.

(2006) applied metrics on a graph structure to assess

the quality of answers in answering services where

people ask and other people give answer. Hotho et

al., (2006) present an approach for analysis of

folksonomies based and their graph representation.

Another representation of information stored in

social systems (e.g. Wikis) is content based

representation. This representation consists only of

the textual (and multimedia) content of the system.

Content based metrics assess the status of texts,

video, audio and pictures. Since wikis still consist

almost solely of text, for this work only text based

content metrics are considered. One very common

approach to assess the quality of text is by means of

reading scores. Examples for reading score based

approaches are Gunning Fog Reading Ease Score,

Flesh-Kincaid Readability Formula (Agichtein et al.,

2008) and the SMOG Reading Score (McLaughlin,

1969). But metrics for content based quality

assessment are not only limited to reading scores.

Graesser et al., (2004) propose, for instance, text

coherence as one indicator relevant for text quality.

In addition they present a framework consisting of

more than 200 metrics for text assessment.

Furthermore resources can be assessed based on

the way they are used in the system. The usage of

resources denotes any interaction of users and

resources in the system. The assumption behind the

application of usage metrics is that if quality of a

resource changes, interaction patterns of this

resource change too. This means users interact

differently with an article if it is of high quality than

a low quality article (Ram and Liu, 2007). Lih,

(2004) shows that there is a direct correlation

between the quality of an article and the number of

edits in a particular time span respectively the

number of unique authors. Cress and Kimmerle

(2008) show that interaction pattern are observable

that lead to a qualitative improvement of an article

and some that do not influence the quality. So it is

both, interactions can influence the quality of an

article and the interactions can be used as indicator

for article quality.

The example in Figure 1 shows the category

Representation of data that covers a set of

dimensions. One of the dimensions of this set is

Ease of understanding. Each dimension is related to

at least one metric. The metric can be seen as

measurement tool for attributes. In the example the

SMOG reading ease score provides a tool for

measuring ease of understanding (McLaughlin,

1969). By nature, metrics are based on a particular

data structure. This structure is provided by the

lowest level of abstraction, the system

representation. In case of the SMOG metric a textual

representation is required as input.

The approach for assessing quality described in

this section proposes a multi layered model

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

212

representing the qualitative status of a resource.

Since the assessment only covers the resource

perspective, individual (task-dependent) user quality

requirements are not covered by this approach. The

following section describes how quality dimensions

can differently weighted depending on the users

current context.

3 USER CENTERED QUALITY

ASSESSMENT

Quality of information is a very general term, (Juran,

1992) defined information quality as data that is fit

for use in their (the users') tasks. This definition

suggests that quality is strongly connected to the

user and her/his requirements (Cappiello et al.,

2004). If we assume that information quality can be

measured by looking at the performance of a system

which is based on that information (Ivanov, 1972),

we still must acknowledge that for social media the

performance can differ depending on the target

groups: different users may assess the quality of one

and the same Wiki article completely different

depending on their situation and current tasks. This

means, since the objective is to assess the quality of

social content, one can never assess quality without

having information about the consumer of the data

in the social system (Klein, 2001).

To a certain extent, quality requirements which

are based on situational aspects may depend on the

background knowledge of a user, or the user’s

experience in a certain area. An expert for a topic

would assess the quality of an article differently than

someone who is new to this topic. Similarly, a child

may have different quality requirements than an

adult. Furthermore, for assessing quality we have to

consider intentional and motivational aspects of the

users (Pipino et al., 2002). The current task and the

reason why the user consumes social media are

decisive for quality perception. If a user wants to get

an overview over a certain topic, the user’s

perception of quality may differ from the perception

of a user who wants to know as much as possible

and hopes to find entry points for further

information sources. Therefore, quality cannot be

assessed in general but rather for a user or a

community with similar quality requirements. The

quality of the same wiki article is perceived

differently if the article is read on a computer screen,

printed out or presented on a mobile device.

This section proposes an approach for quality

assessment in social systems based on user

requirements. Therefore we present a procedure of

steps for identifying how different quality

dimensions are weighted by the user.

Quality assessment goes hand in hand with the

elicitation of individual quality perception. The first

step is the elicitation of the individual weighting of

quality dimensions that reflect the user’s quality

requirements. That means to represent the quality

requirements for each user in a quality profile that

subsequently facilitates the provision of an adaptive

system behavior based on the users quality needs. In

the following, two different methods for identifying

relevant quality dimensions and establishing the user

quality profile are presented.

The first approach is characterized by explicitly

asking the user which quality dimensions she/he

perceives as most important. In order to ask the

people which quality attributes they perceive as

important a questionnaire is presented in the log-in

process (Figure 3). The foundation of this approach

is the empirical selection of quality dimensions (see

Table 1) described in Wang and Strong (1996).

Figure 3: MediaWiki quality requirements elicitation

plugin.

One drawback in their approach is that the

participants of the study of Wang & Strong were

asked without reference to a particular system even

though the perception of quality is also dependent of

the used system. Therefore requirements elicitation

in this approach is conducted directly within the

system that should be assessed in terms of quality to

overcome this problem.

One way of explicitly weighting quality

dimensions is to use a build-in questionnaire. We

developed such a questionnaire as MediaWiki

plugin. After successful login the questionnaire is

presented (cf. Figure 3). The information from the

questionnaire is required to map the quality of a user

A USER CENTERED APPROACH FOR QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN SOCIAL SYSTEMS

213

profile to a particular task.

The second approach describes the implicit

dimension weighting process. Here the user assesses

the quality of articles using embedded rating

buttons. The buttons are added to each page that

contains text. While the user browses through the

wiki, she/he can click the green button if she/he likes

the content or otherwise click the black button.

In this way the user makes an explicit statement

of the quality of an article but does also implicitly

select quality attributes. Therefore after each rating,

all available metrics calculate values for the page

that was rated. If the rating is positive, the system

searches for metrics which show high values for the

given text. Since each metric in the system is

connected to a quality attribute, this method

implicitly provides candidates for quality attributes.

To assess if the value of a metric is high/low in a

particular case, the deviance from the median of the

Wiki article corpus is calculated. The following

formula (1) shows how metrics are selected

implicitly based on user rating. M represents the

Metrics, P the article with i as id (from 0 to n),

Mcurrent is the current metric and T the threshold

for a metric.

(1)

Example: A user rates ten articles as good

quality articles. For all these articles the values for

the RES (Laughlin et al. 1969) metric and the

interaction metric are very high. The RES metric is

connected to the Readability attribute because it

correlates with the readability of the text. The

interaction metric shows that the article is updated

very often, it is connected to the quality attribute

Up-To-Date. Since the user apparently perceives

articles that are easy to read and up to date as high

quality articles, these attributes are stored in the user

profile.

4 EVALUATION

The evaluation is divided into two parts. The first

part addresses the question if the measured quality

of content corresponds to the perception of the user.

In particular, we evaluate whether resources that

would be recommended to the user have the

qualitative status required by the user. The second

part evaluates the assumption that for different tasks

different aspects of quality are important. We

analyze if users perceive quality differently

depending on their current tasks.

The aim of the first part of the study is to

compare the calculated quality status of a resource

and the user quality perception of this resource.

Therefore we used the Wiki questionnaire plugin

(Figure 3) for explicitly weighting the quality

dimensions. In this way we created a quality profile

that represents which quality dimensions are

relevant. For this experiment we assumed that the

context of the user is static, which means the tasks

are always the same. Then we use the rating buttons

to collect quality ratings of Wiki pages given by the

users. Thereby we gathered the information which

articles correspond to the users quality needs. The

next step was to calculate the quality status based on

metric measuring. The objective was to know what

the user understands as good quality, which articles

she rates as good quality and what the system would

recommend as articles that corresponds to the users

needs. The evaluation analyzes whether the system

measures correspond to the users rating. The study

was conducted in an organizational Wiki containing

~2350 articles with ~1750 page accesses per month.

During the test period 78 ratings were given by 18

users. 66 ratings were positive 12 negative. We

identified 2 groups of users with similar quality

requirements and compared the articles rated by

these groups with their quality profiles. The

dependant variable in this experiment is the number

of dimensions that are similar in the resource status

and the user profile. The independent variable is the

threshold which defines similarity. A threshold of

100% means the values are identical, 50% means

both values are higher/lower than system average.

The result shows for 50% threshold a correlation of

10 of 12 dimension, in the other group a correlation

of 8 dimensions. For 75% still 8 respectively 6

dimensions correlate.

Figure 4: Comparison of user profiles created from

implicit and explicit data.

The focus of the second part is evaluating

different weightings of quality dimensions for

different tasks (see description below). The results

presented in this section evolved in line with the

evaluation of a prototype in the MATURE project.

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

214

The participants of this study have been personal

advisors from the career guidance sector in the UK.

During this study the participants used a widget

based information system (cf. Weber et al., 2010) for

several tasks. After completion of the given tasks a

group of expert users filled in the survey. The survey

contained eight questions. For each of the four tasks

the participants were asked how relevant particular

quality dimensions are. The 20 quality dimensions

evaluated in the survey were given by Wang &

Strong (1996).

The tasks were selected according to the familiar

work tasks of the end-users. So the first phase of the

study was to gather relevant tasks from the end-users

by interviewing them. The tasks were divided in two

task groups: the first, group is about receiving

information e.g. by searching. The second group is

about providing information, like writing articles.

The questionnaire was filled in by 5 area

managers as proxy for 25 personal advisors in

different areas. The result represents the mean

values of the answers. In spite of the small number

of participants, the consensus in the answer values

(variance .05p) shows the correctness and the

discrimination of the dimensions values. The fact

that the experts could rate all dimensions for their

areas shows the applicability of the dimension set in

this context. The summary of the results shows that

the relevance of quality dimensions is weighted

differently for various tasks. Figure 5 shows the

cumulated values of the answers for the four tasks.

One noticeable fact is that some of the quality

dimensions are rather depending on a specific task

while others are similar for all tasks. For example

the quality dimension Completeness and

Believability (Figure 5-3) seem to be important

independently of the task, while Cost Effectiveness

states a rather marginal relevance for the selected

domain. In contrast, some values are obviously

dependant on the task. In the case of Concise the

relevance for the second and third task is high

whereas it is low for the first and forth task. The

dimension Timeliness is assessed higher for task 1

and 3 than for task 2 and 4. Regarding the fact that

task 1 and task 3 are tasks that address the quality of

resources that are presented to the user and task 2

and 4 are tasks where the user provides information

the different weights of the quality dimensions make

sense. Timeliness is assessed very important for task

1 and 3 (both of them are about providing

information for other users) whereas it is less

important for 2 and 4 (consuming information from

the system).

Figure 5: Weighting for quality dimensions of different

tasks.

5 CONCLUSIONS

The objective of this paper is to propose an approach

for quality assessment in social systems.

Therefore we raised three questions in the

beginning: First, how can the quality need of the

user be detected and represented? Second, how can

we measure the qualitative status of a resource?

Third, how can we map the resource quality status to

the user quality requirements in order to provide

resources that comply with the users´ quality needs?

The foundation of this work is based on the

awareness that quality is individual and even

depending on the current situation of the user. In

order to provide quality adaptive system behaviour,

the context of the user has to be known. The context

of the user is decisive for the relevance of each facet.

Hence, the quality requirements of the user can be

expressed as fine granular facets of the concept

quality. In this work we argue the importance of

considering the context of the user and propose an

approach for explicitly and implicitly evaluating the

users quality needs.

The task of mapping user quality needs to

resource quality statuses can be accomplished by

specialization of the quality concept on the one hand

and abstraction of the resource status on the other

hand. The resulting quality dimensions and the

metric values are on the same level of granularity

(abstraction/specification) and can so directly be

mapped. The result from the empirical study is that

some quality dimensions depend on a specific task

while others are task independent.

Further research will cover finding algorithms

for quality profile mapping in large datasets.

Clustering articles according to their quality profile

in real-time is still a problem. Due to the increasing

amount of multimedia content another direction for

further research is the qualitative assessment of

images, audio and videos. This would require the

A USER CENTERED APPROACH FOR QUALITY ASSESSMENT IN SOCIAL SYSTEMS

215

enhancement of the exiting metric set with

multimedia metrics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work has been partially funded by the European

Commission as part of the MATURE IP (grant no.

216346) within the 7th Framework Programme of IST and

as part of the FP7 Marie Curie IAPP project TEAM (grant

no. 251514).

The Know-Center is funded within the Austrian

COMET Program - Competence Centers for Excellent

Technologies - under the auspices of the Austrian Ministry

of Transport, Innovation and Technology, the Austrian

Ministry of Economics and Labor and by the State of

Styria.

REFERENCES

Agichtein, E., Castillo, C., Donato, D., Gionis, A., &

Mishne, G. (2008). Finding high-quality content in

social media. Proceedings of the international

conference on Web search and web data mining -

WSDM ’08, 183. New York, New York, USA: ACM

Press.

Ahn, T., Ryu, S., & Han, I. (2007). The impact of Web

quality and playfulness on user acceptance of online

retailing. Information & Management, 44(3), 263-275.

Cappiello, C., Francalanci, C., & Pernici, B. (2004). Data

quality assessment from the users perspective.

international workshop on Information quality, 68-73.

Cress, U., & Kimmerle, J. (2008). A systemic and

cognitive view on collaborative knowledge building

with wikis. The International Journal of Computer-

Supported Collaborative Learning, 3(2), 105-122.

Springer New York.

Delone, W., & McLean, E. (2003). The DeLone and

McLean model of information systems success: A ten-

year update. Journal of management information

systems, 19(4), 9-30.

Dom, B., Eiron, I., Cozzi, A., & Zhang, Y. (2003).

Graph-based ranking algorithms for e-mail expertise

analysis. Data Mining And Knowledge Discovery.

Giles J. Internet encyclopedias go head to head. Nature.

2005;438(7070):900–901..

Graesser, A. C., McNamara, D. S., Louwerse, M. M., &

Cai, Z. (2004). Coh-metrix: analysis of text on

cohesion and language. Behavior research methods,

instruments, & computers: 36(2), 193-202..

Hotho, A., Jaschke, R., Schmitz, C., & Stumme, G.

(2006). Information retrieval in folksonomies: Search

and ranking. The Semantic Web: Research and

Applications, 411–426. Springer.

Ivanov, K. (1972). Quality-control of information: On the

concept of accuracy of information in data banks and

in management information systems. The University

of Stockholm and The Royal Institute of Technology.

Doctoral dissertation.

Jeon, J., Croft, W. B., Lee, J. H., & Park, S. (2006). A

framework to predict the quality of answers with non-

textual features. Annual ACM Conference on

Research and Development in Information Retrieval.

Juran, J. M. (1992). Juran on Quality by Design (p. VI +

538). The Free Press.

Klein, B. D. (2001). User perceptions of data quality:

Internet and traditional text sources. Journal of

computer information systems, 41(4), 9–15.

McLaughlin, G. H. (1969). SMOG grading: A new

readability formula. Journal of reading, 12(8), 639–

646.

Pipino, L. L., Lee, Y. W., & Wang, Richard Y. (2002).

Data Quality Assessment. Communications of the

ACM, 45(4), 211-218.

Ram, S., & Liu, J. (2007). Understanding the semantics of

data provenance to support active conceptual

modeling. Active conceptual modeling of learning,

17–29. Springer.

Wang, R.Y., & Strong, D. M. (1996). Beyond accuracy:

What data quality means to data consumers. Journal of

management information systems, 12(4), 33. ME

Sharpe, Inc.

Weber N., Nelkner, T., Schoefegger, K., Lindstaedt, S. N.,

(2010). SIMPLE - a social interactive mashup PLE.

In: Fridolin Wild and Marco Kalz and Matthias

Palmér and Daniel Müller (eds.): Proceedings of the

Third International Workshop on Mashup Personal

Learning Environments (MUPPLE10), in conjunction

with the 5th European Conference on Technology

Enhanced Learning (EC-TEL2010), 2010

KMIS 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing

216