ACQUISITION OF SERVICE PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE

BASED ON ONTOLOGIZED MEDICAL WORKFLOW

Taisuke Ogawa

1

, Mitsuru Ikeda

1

, Muneou Suzuki

2

, Kenji Araki

2

and Koiti Hasida

3

1

School of Knowledge Science, Japan Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Nomi-shi Asahidai, Ishikawa, Japan

2

Medical Information Technology, University of Miyazaki Hospital, Miyazaki, Japan

3

Social Intelligence Technology Research Laboratory, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology

Tokyo, Japan

Keywords:

Practical knowledge, Medical service, Sense of value, Purpose oriented, Ontology.

Abstract:

It is ideal to provide medical services as patient-oriented. The medical staff share the final goals to recover

patients. Toward the goals, each staff has practical knowledge to achieve patient-oriented medical services.

But each medical staff has his/her own priorities and sense of value, that derive from their expertness. And

the results (decisions or actions) from practical knowledge sometimes conflict. The aim of this research is

to develop an intelligent system to support externalizing practical wisdoms, and sharing them among medical

experts. In this article, the author propose a method to model each medical staffs’ sense of value as his/her way

of task-understanding in medical service workflow, and to obtain the practical knowledge using the models.

The method was experimented by developing a knowledge-sharing system base on the method and running it

in the Miyazaki University Hospital.

1 INTRODUCTION

Service science is an attempt to seek a scien-

tific/engineering framework, in order to sophisticate

continuously that service, by defining it as the ac-

tions and activities through which one person serves

another (Yoshikawa, 2008). This paper proposes that

information and knowledge for the design and evalua-

tion of such services be shared not only among service

providers, but also among service recipients (which

we call an intelligence cycle). This study uses a sci-

entific framework to understand the phenomenon that

service values vary depending on the subjectivity of

the stakeholder. Knowledge engineering is widely ex-

pected to serve as a basic technology to support the

intelligence cycle and value creation, but there are

enormous variations in targets—such as knowledge

and problems. Therefore, this study seeks to estab-

lish a new system to support the sharing of practical

knowledge to convey medical information and knowl-

edge in consideration of individual patient conditions

when medical professionals provide medical services

(hereafter “practical knowledge”), as an application

of knowledge engineering for medical services.

A system of knowledge engineering has been

investigated wherein knowledge can be shared and

reused in the medical field from an early stage of

development, and through which medical knowledge

can be obtained and used to help solve problems such

as computer-aided diagnosis (glaucoma CASNET

(Weiss and et al., 1977), internal disease Caduceus

(Myers and et al., 1982), and infection Neomycin

(Clancey, 1983)). In addition, an ontology for shar-

ing medical knowledge has been studied in line with

the development of knowledge sharing via the Inter-

net. For example, the EON project (Tu and Musen,

2001)(Musen and et al., 2006) has studied a patient-

oriented clinical decision support system by modeling

clinical guidelines. Likewise, the SAGE project (Tu

and et al., 2007) has investigated a methodology for

modeling guidelines in the light of the GLIF3 stud-

ies (Boxwala and et al., 2004), and PROforma (Sut-

ton and Fox, 2003), which demonstrate a modeling

method to create a medical workflow to appropriately

explain the context of medical practice. (Hurley and

Abidi, 2007) is a study of the construction of a clin-

ical path (discussed later), which is one of the tran-

scriptions of a medical workflow, and Abidi attempts

to unify a clinical path and knowledge from the guide-

lines based upon the Hurley study (Abidi, 2009).

These studies on medical knowledge support the

sharing of the knowledge that medical services can

118

Ogawa T., Ikeda M., Suzuki M., Araki K. and Hasida K..

ACQUISITION OF SERVICE PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE BASED ON ONTOLOGIZED MEDICAL WORKFLOW.

DOI: 10.5220/0003719401180130

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development (KEOD-2011), pages 118-130

ISBN: 978-989-8425-80-5

Copyright

c

2011 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

provide. In comparison, our study focuses on the ac-

quisition and sharing of knowledge (practical knowl-

edge) on how to provide a service after that service

is established from the standpoint of patients. In

particular, this paper proposes a method to structure

knowledge-acquisition interviews in which experts

(medical professionals who provide medical services

in this study) are asked about their practical knowl-

edge.

Previous studies on knowledge acquisition clas-

sified the knowledge of experts into the references

used, the knowledge content, and the implementa-

tion of the modeling (KADS methodology (Schreiber

and et al., 2000)), the defined nature of problems,

and a problem-solving method as task knowledge

to enhance the reusability of the knowledge, and

used them in knowledge-acquisition interviews (SIS

(Kawaguchi et al., 1989), Prot´eg´e (Gennari et al.,

2003), and others). In these cases, knowledge about

tasks pertaining to the problems was used to ac-

quire knowledge in order to solve problems. A

method to conduct interviews with respect to the

conceptual structure of tasks whose type is speci-

fied (ROGET (Bennett, 1985)), generic tasks that

are defined by concepts with a high general ver-

satility (Chandrasekaran, 1986), and a system for

knowledge-acquisitioninterviews (MULTIS (Tijerino

and et al., 1993)) based on modeling by task ontology

that was developed based on the above-mentioned

items (Mizoguchi and et al., 1995) have been pro-

posed. These studies selected targets and conducted

in-depth analyses of the nature of the tasks, which

enables computers to help decide the “what to pro-

vide” of “what to and how to provide” by medical ser-

vices. The authors focus on the fact that knowledge

about “what to provide” plays a role in the prepara-

tion phase of an interview (some practical knowledge

is needed for “what” to do) when conducting a practi-

cal knowledge-acquisition interview to inquire “how

to provide.” This study proposes a modeling method

for logical medical tasks. The modeling of medi-

cal tasks aims to help medical professionals under-

stand their own values and purposes (called an “un-

derstanding of services” by medical professionals),

which demonstrates the recognition level of the tasks

of medical professionals. Medical-service providers

such as doctors and nurses share the same final goal—

that patients regain healthy and comfortable physical

and mental conditions—but they have different exper-

tise. Therefore, they sometimes find their own values

and purposes for a task, which may influence their

practical knowledge. To be more specific, the value

of medical service tasks, which is a subjective and

vague factor, is modeled, and a method is studied

to conduct modeling at an appropriate level to share

information. The modeling focuses on a knowledge

medium of a clinical path (hereafter “Path”). Path

is defined as a standard workflow for typical cases

(Coffey, 2005) and guarantees a minimal medical care

quality (Tachikawa and Abe, 2005). This concept has

been spreading rapidly. A path is made by integrat-

ing the opinions of experienced medical profession-

als. It is considered that the modeling of the contents

of a Path from the above-mentioned viewpoints may

enable a differentiated understanding of medical ser-

vices provided by medical professionals, and that the

result may clarify the acquisition of practical knowl-

edge.

This paper proposes a method to differentiate the

understanding of medical services by medical pro-

fessionals by Path-modeling based upon an ontology

(see Section 3), and demonstrates a technique to use

the model for a practical knowledge-acquisition in-

terview (use as a handle to acquire knowledge) (Sec-

tion 4.2). The technique was included in the system

(Section 4), and verified in the University of Miyazaki

Hospital (the Hospital), (Section 5).

2 CONCEPT FOR A SUPPORT

SYSTEM FOR SHARING

PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE ON

MEDICAL SERVICES

Medical professionals are required to provide patient-

oriented medical services. They obtain the knowl-

edge they need about patients by means of trial and

error when providing medical services, as shown in

Fig. 1. Such acquisition may be supported by ad-

vice and the experience of other medical profession-

als such as seniors and colleagues. This study terms

such advice and experience “practical knowledge” (in

a broad sense). This practical knowledge is quite di-

versified, and varies depending upon the conditions

of the patients, the extent to which medical services

are provided, and the sense of values of the providers.

In sharing support of practical knowledge, medical

professionals should consider how to access practical

knowledge after the necessary information has been

obtained, for example, in which phase patients are—

the acute phase, the recovery phase, or the mainte-

nance phase, and who is responsible for making deci-

sion (whether the patient can decide for themselves or

whether medical professionals need to make the deci-

sions because of the extreme urgency of a situation).

This study focuses on practical knowledge during the

recovery phase (during a hospital stay). Observations

ACQUISITION OF SERVICE PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE BASED ON ONTOLOGIZED MEDICAL WORKFLOW

119

Figure 1: Practical knowledge to support patient-oriented

medical treatment.

made during the provision of medical services during

hospitalization reveal that there is some typicality in

the conditions of patients and this has been standard-

ized by the clinical path and other factors. This study

seeks to create a model for computer processing such

as typicality in patients’ conditions and a standard-

ized service in order to establish a system of provi-

sion based upon practical knowledge that simultane-

ously enables the conducting of practical knowledge-

acquisition interviews by computer and the use of an

electronic health record system.

Recently, standard medical treatment has been

scheduled for typical cases in clinical settings in an

attempt to secure a minimal quality of medical ser-

vices. A clinical path is a knowledge medium to de-

fine such medical services (Fig. 2). A Path contains

inclusion/exclusion criteria, medical tasks, outcomes,

and other factors. Each hospital formulates and uses

its own Path by trial and error. The Hospital, which

conducted this study, introduced an electronic health

record system based on a Path in 2006, and uses 150

or more clinical paths. The Hospital reports that the

introduction of the system has reduced the number of

instructions and orders required to carry out routine

work, and that it has rationalized medical treatment.

In contrast, another survey on the use of a clinical

path (Kato and et al., 2005) reported that there was

concern that the “use of a clinical path interferes with

thinking in clinical settings.” In addition, a guide for

the introduction of a clinical path ((Fukushima, 2004)

and others) emphasized that “a Path is not a schedule.

It is tool for thinking about good medical practice.”

Concerns about the use of a Path can be summarized

as follows.

• The use of Path decreases communication among

medical staff and decreases opportunitiesfor shar-

ing knowledge, and

• Medical staff feel comfortable in implementing

medical practice according to Path and cease to

think for themselves.

Figure 2: Clinical pathway.

This study aims to establish a system to promote

practical knowledge sharing by using an electronic

health record system based on Path in order to elimi-

nate concerns about a lack of communication among

medical staff. The targeted practical knowledge in-

cludes strategies after a decision has been made as

to which medical tasks are to be provided, for ex-

ample, strategies to offer safer treatment and higher

satisfaction for patients, as well as guidelines to im-

plement the strategies, and the contents of commu-

nications among medical professionals and between

medical professionals and patients.

Figure 3: Support system for sharing practical medical

knowledge.

In order to integrate practical knowledge sharing

into the use of Path, the most important thing is that

an understanding of the services provided by medi-

cal professionals is clearly specified (how they think

about their patients and what they are trying to pro-

vide to their patients). In general, medical profession-

als share the goal of returning patients to health, but

KEOD 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

120

their sense of values varies depending on their spe-

cialty and personality (Yoshitake and others point out

this conflict, which is part of the difficulty in reach-

ing agreements in clinical settings (Yoshitake, 2007)),

which may influence the conditions of patients, an un-

derstanding of their feelings, and the priority of the

projected outcomes. That is, medical professionalsf

understanding of service defines the significance of

practical knowledge.

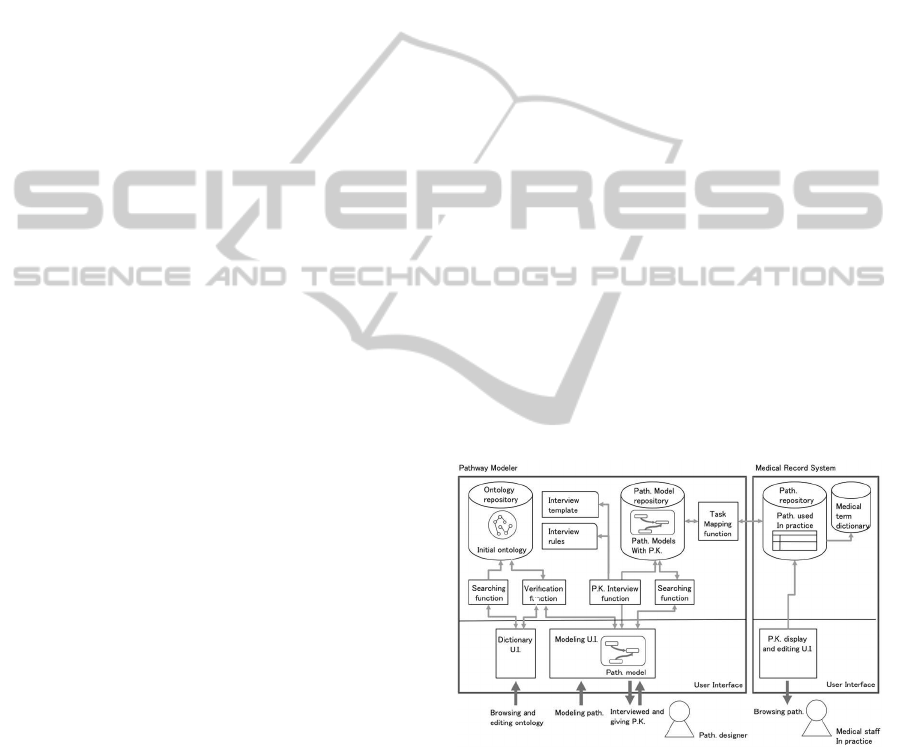

Figure 3 shows the concept of the support system

used in this study. The system for the preparation of

Path (1 to 5 in the figure) shows that the framework

for an understanding of the services provided by med-

ical professionals is modeled based upon an ontology

(Section 3). Our method is to use the model as a han-

dle to obtain knowledge from medical professionals

(hereafter “the knowledge handle”) at the time of the

interview to acquire the practical knowledge (6 to 7 in

the figure), and this is presented in Section 4.

3 MEDICAL WORKFLOW

MODELING BASED UPON

MEDICAL SERVICE

ONTOLOGY

3.1 Modeling the Understanding of

Services by Medical Professionals

As mentioned, this study models medical workflow to

clearly specify the understanding of services provided

by medical professionals. This model aims to express

the intention of the design of Path, and is intended to

be used as a step prior to interviewing medical pro-

fessionals about their practical knowledge (how they

recall their medical practice). Specifically, this mod-

eling aims to identify the purpose that medical profes-

sionals find in the medical practices (tasks) that con-

stitute workflow, and how they correlate their purpose

with other medical practices, and to what level and

extent.

3.2 Guideline for Construction of an

Ontology

The construction of an ontology for the modeling of

an understanding of service has two entangled prob-

lems.

• There are no agreed common words to express

difference in ways of thinking

• Difference in ways of thinking arises when a con-

crete Path is reviewed.

At the time of designing a Path, medical profession-

als have repeated discussion held to share their un-

derstanding of “service.” This study seeks a method

to prepare a vocabulary (ontology) to facilitate com-

munication. It is desirable that an ontology be pre-

pared prior to communication, but it is communica-

tion that causes difference in the understandingof ser-

vice. Thus, there is a dilemma as to which one should

(or can) acquire first—the content or the means to ex-

press the content.

In light of these problems, a method of construct-

ing an ontology is prepared by dividing the task into

the early phase and continuous phase.

• Early phase: By focusing on the understanding

of service, extract the necessary concepts for the

modeling of medical practice in order to prepare

the ontology (“early ontology”)

• Continuous phase: Model the understanding of

service according to the early ontology at the time

of the design and revision of a Path. If there are

no necessary concepts for the modeling (no match

with the modeling) in it, it should be added to the

ontology (or the ontology should be revised).

Knowledge engineers interview medical profes-

sionals during the early phase. Medical professionals

take the lead in constructing the continuous phase af-

ter a system utilizing the early ontology is completed

(the result is reviewed by a knowledge engineer). The

following two points were the focal points of the con-

struction of the method.

• Accept ambiguities and errors when adding to the

ontology and using the ontology

• Receive the benefits of the ontology immediately

3.3 Medical Service Ontology

As mentioned, the modeling of medical services is

aimed at clarifying the understanding of services pro-

vided by medical professionals. This section summa-

rizes the ontologyso as to make it easier to understand

the purpose of this modeling. The early ontology was

prepared by analyzing the Path in a liver biopsy under

the condition that the clinical paths used in the Hos-

pital have been used for a long time and are simple.

The selection of a Path whose contents have been ac-

cepted by all medical professionals can avoid unnec-

essary discussions about medical practice and allow

for a focus on the ontology used. As an environment

for ontology construction, Semantic Editor (Hasida,

2007) was used. A method to express differences in

ways of thinking by medical professionals is summa-

rized as follows.

ACQUISITION OF SERVICE PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE BASED ON ONTOLOGIZED MEDICAL WORKFLOW

121

Figure 4: Medical service ontology.

• What medical goals do you find in each medical

task?

• How do you structuralize medical tasks to accom-

plish these medical goals?

Fig. 4(a) shows medical ontology. For medical pur-

poses, highly abstract goals, such as the enhancement

of therapeutic effect, risk reduction, and enhancement

of a patient’s Quality of Life (QOL), are given prior-

ity. The enhancement of a patient’s QOL includes a

reduction of physical and mental burdens.

Medical purpose is a term used to express how

much the goal of accomplishing each medical task of

their medical services means to medical professionals

(which may vary depending on specialty and the role

played by each medical professional).

Fig. 4 (b.1, 2) show concept configurations for

medical tasks. Medical tasks consist of a “performer”

who deals with the tasks; “input”, which are items

handled in the task, such as patients and samples col-

lected from patients; and “output” which is goods, in-

formation, and knowledge obtained when the task is

conducted; and “part tasks,” which are parts of a task

(the opposite term is “whole task”). The task includes

one or more medical purposes. Each task has the pur-

pose of the task itself and a purpose from higher tasks.

Medical tasks are classified into tasks to do (actions

that influence the real world, such as treatment to pa-

tients) and tasks to think about (actions that do not

influence the real world, such as diagnosis and deci-

sion making) in order from the highest medical tasks

downward.

By clarifying that medical tasks for a medical pur-

pose and that the relationship between the medical

tasks and medical purpose have been clarified, the

modeling for the understanding of a service by medi-

cal professionals is achieved. A Path as used in clin-

ical settings never includes tasks to think about , be-

cause a Path is used only for progress management

of medical practices, and because the method of con-

ducting medical practices and the decision on what to

do are left in the hands of individual medical staff.

The modeling reveals not only tasks to do, but also

tasks to do in the mind (diagnostic tasks). The un-

derstanding of service by medical professionals is ex-

pressed by how much and how they are correlated

with the treatment provided.

3.4 Examples of Modeling of

Understanding of Service

This section explains how an understanding of ser-

vice by medical professionals is expressed as a model.

Figure 5 shows a model of one of the medical tasks set

in a Path, which includes a medical procedure, “walk-

ing patients to the toilet.”

Figure 5: Model of the medical task “walk patients to the

toile”.

This medical task evaluates patient recovery (for

medical purposes). A prerequisite of the medical task

is urination via a catheter, and the requirement for the

KEOD 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

122

medical task is the removal of the catheter. In addi-

tion, the task has the purpose of decreasing an infec-

tion risk (B) by removing the catheter as soon as pos-

sible, because once inserted a catheter may become

contaminated and cause an infection. The removal of

the catheter enables the provision of better mobility

to patients and encourages patients to move about in

order to accelerate their recovery (C). In considera-

tion of these purposes, a catheter should be removed

as soon as possible, which sets the timing of the med-

ical task “walking patients to the toilet.” At the same

time, there is a secondary medical task of “judging

whether patients can walk,” which is aimed at secur-

ing the safety of patients (A). In this case, it is not

always necessary to accelerate the timing for when

patients can walk to the toilet.

Such modeling of medical tasks helps find mul-

tiple purposes. In the above-mentioned purposes, A

and B “focus on risk reduction” as the purpose of the

medical practice, while C places a “focus on the rapid

recovery of health,” which may be set according to

the specialty of the medical professional in question.

Therefore, the timing and method of a series of med-

ical practices may vary depending on purpose, which

suggests that acquisition of the practical knowledge

may need clarification for each purpose. However,

it is difficult to comprehensively systematize in ad-

vance that each medical task has a medical purpose.

It is more practical that systematization be gradually

arranged throughout the continuous phase of the con-

struction of the ontology.

4 SUPPORT SYSTEM FOR

SHARING PRACTICAL

KNOWLEDGE ON MEDICAL

SERVICES

As mentioned in Section 2, a support system for shar-

ing practical knowledge on medical services has been

established by: expressing as a model the understand-

ing of medical services by medical professionals; ac-

quiring practical knowledge by an interview function

based upon the model; and providing practical knowl-

edge acquired in clinical settings via an electronic

health record system. This section explains “Path

modeler,” which is a tool that has the functions to

model the understanding of services by medical pro-

fessionals and interviews about practical knowledge,

and which can provide practical knowledge (and is

equipped with the electronic Path (medical record)

system used in the Hospital).

4.1 Path Modeler

Path modeler is a tool through which medical profes-

sionals can discuss the design intent of Path, which

has a framework and vocabulary through which to ex-

press the ideas of medical professionals on medical

service (understanding of service). The framework is

based on an ontology, as described in Section 3, and

it has a mechanism through which it can be gradu-

ally developed by modeling an ontology to be used in

meetings on the design of and revision to Path. Repre-

sentatives of medical professions attend the meetings

to discuss the contents of Path. Health information

managers, who are considered the end-users of the

tool because basic ontology literacy is required to use

Path modeler, also participate in meetings and deal

with issues of computerizing the content of Path (en-

try into an electronic Path system).

Path modeler is implemented as a JAVA applica-

tion. Figure 6 shows the configuration of the system,

which includes a repository for the ontology, and a

support system for the modeling of medical services

and practical knowledge interviews. Semantic Au-

thoring Server (Hasida, 2007) handles the ontology

repository as well as ontology editing and sharing

from multiple clients.

Modeling procedures using Path modeler for the

understanding of services by medical professionals is

explained here. Figure 7 shows the user interface.

Figure 6: Structure of functions of Path modeler.

A task for discussion on design intent is displayed

on the main viewer (a in Fig. 7). As the tasks neces-

sary to explain the design intent of the task are added,

the relation with these tasks is described as a link. At

the same time, the ontology panel (b in Fig. 7) is used

as a dictionary (adding the necessary ontology if it

is not defined). Detailed information, such as “who

uses the task and for what purpose,” is registered in

the detailed information panel (c in Fig. 7) (modeling

is described in detail in Section 4). While the purpose

ACQUISITION OF SERVICE PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE BASED ON ONTOLOGIZED MEDICAL WORKFLOW

123

Figure 7: Interface of Path modeler.

and value of medical tasks by medical professionals

are expressed by modeling, any relation with tasks

for realization is expressed as a model. The interview

panel (d in Fig. 7) obtains the practical knowledge ac-

quired through interviews using the knowledge han-

dle, and performs a practical knowledge-acquisition

interview using the resulting model, based upon the

relation between the targeted medical task and other

medical tasks. The details of this are described in the

next section.

4.2 Practical Knowledge Acquisition

using a Model and the Knowledge

Handle

The interview functions are set to ask questions of

Path designer about practical knowledge in light of

the relation between the purpose of the task and other

tasks. The interaction between Path designer and the

system is as follows.

1. Path designer selects a task that he/she pays atten-

tion to or wants to accomplish.

2. The system checks the applicability of the knowl-

edge to the task selected by the Path designer and

decides upon the type of practical knowledge to

be utilized in the task.

3. The system explains the understanding of the ser-

vice based upon the relation between the selected

task and related tasks, and asks questions about

the practical knowledge needed.

4. Practical knowledge is acquired from the answers

provided by Path designer.

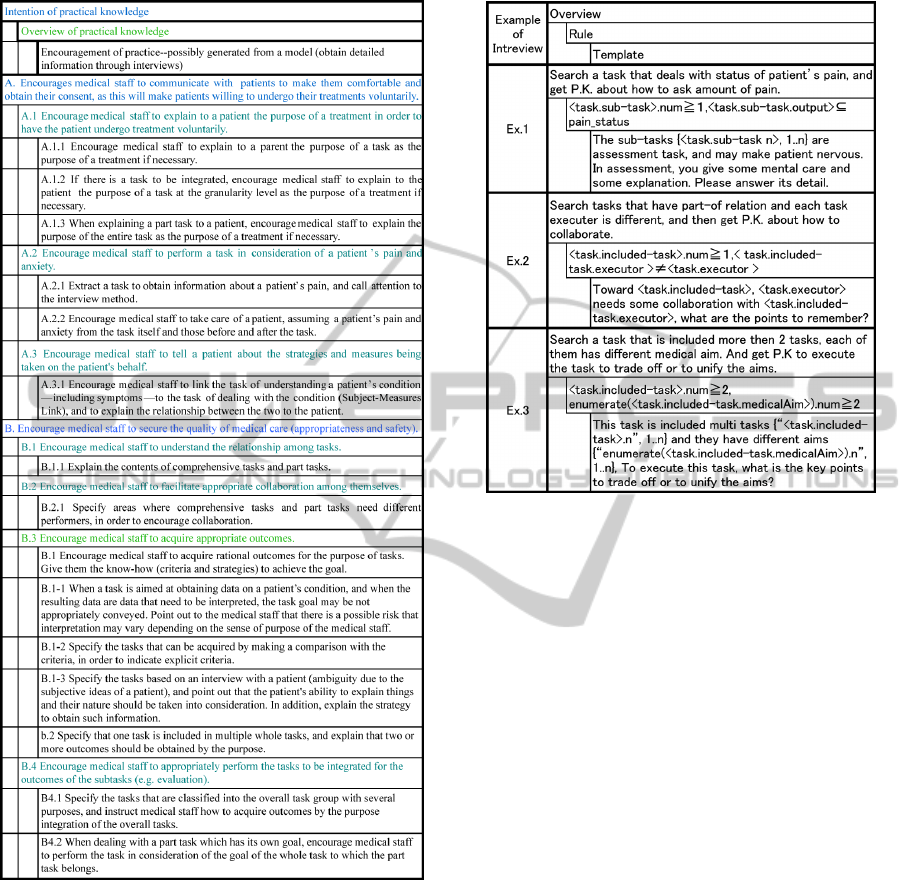

Table 1 shows a sample interview created from the

model. The words in black in the table explain the

way of thinking of Path designer about medical ser-

vices (what level the tasks are and how they are re-

lated), while the words in blue ask questions based

Table 1: Example interview.

Table 2: Example answer.

upon them. Table 2 shows answers to the questions.

Table 4 shows that the knowledge handle defines the

type of interview to the model (a handle to obtain

knowledge). The knowledge handle consists of prac-

tical knowledge patterns (Table 3), rules, and tem-

plates. The knowledge handle is created in accor-

dance with the following procedures.

1. Make a model using Path modeler.

2. The knowledge engineer explains the content of

the model to medical professionals who cooperate

in creating the knowledge handle, and asks them

to evaluate the appropriateness of the content.

3. Samples of practical knowledge are collected

from the medical professionals.

4. The practical knowledge samples are analyzed by

the knowledge engineer and the medical profes-

sionals, and the features of the practical knowl-

edge pattern are abstracted and described as “type

of practical knowledge.”

KEOD 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

124

Table 3: Pattern of practical knowledge.

5. An effective aspect of the type of practical knowl-

edge is encoded as a rule, based upon the practical

knowledge described in the step 4.

6. Templates are prepared for descriptions and ques-

tions for the tasks so as to obtain practical knowl-

edge from samples.

Table 3 shows types of practical knowledge. The

largest category was defined as “Intention” to ac-

quire practical knowledge, and the second-largest cat-

egory was defined as “Summary” of achievement of

the intention, which was further divided into concrete

“Method.” For example, practical knowledge with In-

tention “A. Provide a sense of safety and understand-

Table 4: Knowledge handle.

ing to patients to encourage them to undergo treat-

ment” includes “A.2. Medical staff conduct the task

in consideration of the pain and anxiety of patients,”

and as the concrete method, there is “Method 2. Ad-

minister treatment to patients by estimating their pain

and anxiety from the task itself and the previous or

next task.”

This rule is used to decide which type of practi-

cal knowledge should be asked in which task in the

model. The rule is described using task and/or pur-

pose. Table 4 shows some of the knowledge handles.

For example, concepts about pain (the concept of pain

as a subclass and the concept of bearing pain as a

part) are specified in the output in order to find med-

ical tasks that induce pain, when asking a method to

treat patients for their pain (The practical knowledge

pattern, A.2.1). As mentioned above, the knowledge

handle consists of practical knowledge patterns that

medical professionals conduct, the aspect in which

the type of practical knowledge interview is effective

(Rule), and descriptions to interview them about their

practical knowledge. These patterns look like a gener-

alized empirical rule so that the completeness cannot

be guaranteed, but they are positively effective, which

suggests that an accumulation of patterns could grad-

ually improve the completeness.

4.3 Provision of Practical Knowledge

Via Electronic Health Record

The practical knowledge acquired is provided for the

ACQUISITION OF SERVICE PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE BASED ON ONTOLOGIZED MEDICAL WORKFLOW

125

clinical settings via an electronic health record sys-

tem. The Hospital, the venue for this study, uses

an electronic medical record system based upon Path

(electronic Path). This electronic Path system orig-

inally had a function to explain each Path. In this

study, a function to indicate practical knowledge was

added. Accordingly, the Path system matches the Path

items that are defined in Path with the medical tasks

in the Path modeler, which enables practical knowl-

edge to be indicated when items are performed (Fig.

8). The aim of this is to ensure compatibility with

electronic health records, which vary from hospital to

hospital, and to place less of a demand on a critical

system for the electronic health records, by making

the Path modeler independent from electronic health

records.

Figure 8: Interface of Path modeler.

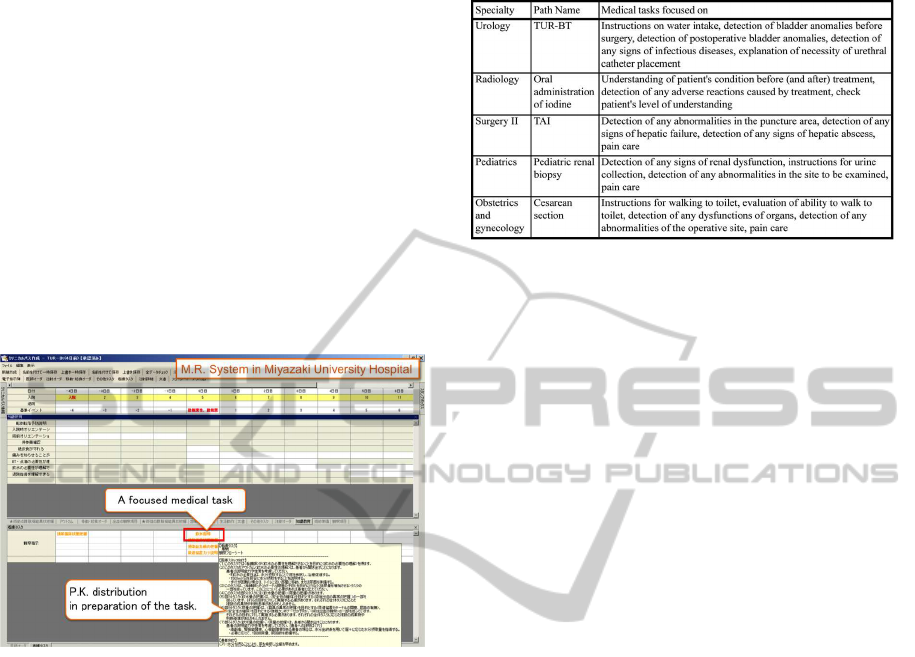

5 OPERATION OF SYSTEM

This section shows the result of the acquisition of

practical knowledge using the Path modeler and the

provision of the acquired knowledge to the clinical

settings, verifies whether the function works as in-

tended, and discusses the rationale of the function.

5.1 Practical Knowledge Acquisition

using Path Modeler and a

Discussion on Acquired Knowledge

5.1.1 Operation Procedures for Path Modeler

The understanding of service by medical profession-

als was modeled and practical knowledge was ac-

quired in the five clinical departments of the Hospital.

Table 5 shows the targeted Path and medical tasks.

The clinical paths were selected in consideration of

experience of long-term use and content that did not

need to be modified in order not to adjust the service

Table 5: Path and medical tasks used in operation.

content but to understand a service whose content had

been agreed upon medical experts. The procedure is

as follows.

1. Modeling of medical tasks in which the under-

standing of service may vary according to occupa-

tion (extract the task from the results of interviews

with medical professionals in the clinical settings,

and modeling by knowledge engineers and doc-

tors in the medical information department.

2. Obtain problems and questions related to the

descriptions (and questions) of the task that is

produced by the interview functions (the report

should be corrected by doctors and nurses in the

clinical setting).

3. Acquire practical knowledge from the answers to

the practical knowledge interview (performed by

doctors and nurses in the clinical settings).

4. Discuss the results of (2) and (3) (performed by

knowledge engineers and doctors in the medical

information department)

5.1.2 Discussion about Modifications of

Descriptions

As mentioned, the descriptions produced by the in-

terview functions help explain the understanding of

service as a model by natural language, and illustrate

the state of the service that is asked of respondents

(medical professionals). When medical profession-

als correct the descriptions, they will understand the

modeling errors and the difference in the understand-

ing of the service modeled and their understanding of

the service. This section discusses the necessity of the

understanding of service by medical professionals at

the time of acquiring practical knowledge in light of

the results.

It was pointed out that there was one modeling

error. There was a task “measurement of hematoma

size” after a kidney biopsy on a child, which was at

first defined as a part task, “wound treatment,” for

KEOD 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

126

Table 6: Sample answers.

nurses. However, medical professionals in the clini-

cal settings pointed out that the description of “wound

treatment” was not appropriate, saying “the size of

this kind of hematoma in a kidney is measured by a

doctor using an ultrasonic echo so that it should not

be included in wound treatment.” Therefore, it was

classified into a part task of the task “diagnosis of

kidney abnormalities” by doctors. This was the only

modeling error, and it was reviewed on a model basis

and confirmed in “Trial use of practical knowledge in

clinical settings” (Section 5.2). Thus, the model is

reviewed and modified by a correction of the descrip-

tions in consideration of the ontology literacy of the

system users, which functions as we expected.

Next, when an understanding was reached that the

service was different from the model, an instruction

was issued to adjust the medical tasks and purposes

to match those of the actual work. For example, con-

cerning the task of “measurement of urine volume” in

the Path for TURBT (transurethral resection of a blad-

der tumor), the entire task of “understanding of blad-

der dysfunction” was changed to “understanding of

urination abnormalities,” and “risk reduction of infec-

tion” for the purpose of “instruction for water drink-

ing” was changed to “prevention of catheter obstruc-

tion.” These instructions expressed the degree to how

much medical professionals understood the medical

knowledge of “bladder dysfunction by knowing the

urinary volume (whether it significantly decreases)

and the fact that a low infection risk can be main-

tained by predicting the chance of catheter occlusion

(catheter occlusion increases infection risk).”

The correction instructions were studied by the

person in charge of the modeling and the person in

charge of correcting the descriptions. According to

the results, it was found to be ideal that these instruc-

tions be explained both before and after the correc-

tions. The task of “understanding of bladder dysfunc-

tion” was evaluated by doctors as a final stage, but the

part task of “measurement of urination volume” was

conducted by nurses. The nurses in charge of this task

understood the task of “measurement of urination vol-

ume” as “understanding of bladder dysfunction” for

the medical purpose, and “urination abnormalities”

for operational purposes. Nurses in charge of the task

of “instruction for water drinking” were also responsi-

ble for the task of “checking catheter abnormalities.”

For nurses, “prevention of catheter obstruction” may

more appropriately express the purpose of “instruc-

tion for drinking water” rather than “risk reduction of

infection” and their actual medical tasks. However,

the description before modification may be more rea-

ACQUISITION OF SERVICE PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE BASED ON ONTOLOGIZED MEDICAL WORKFLOW

127

sonable if the medical purpose is emphasized. Thus,

the descriptions should convey the understanding of a

service containing medical logic, and the understand-

ing of a service that underscores an important point

in promoting work flow in clinical settings. In other

words, it suggests that at least these two types of de-

scriptions are necessary to describe the status of a ser-

vice when interviewing medical professionals about

their practical knowledge.

5.1.3 Discussion about Answers to Questions

about Practical Knowledge

Table 6 shows sample answers to the questions used

to acquire practical knowledge. The total number of

questions was 97 for 23 medical tasks, which were

contained in five clinical paths, of which 88 questions

were answered. Of the nine unanswered questions,

three were invalid due to instructions for modifying

the model structure; four were not necessary because

the content overlapped; and two were excluded for

unknown reasons. Such a high response rate demon-

strated that the function to conduct interviews on the

practical knowledge of medical services in light of

the understanding of service by medical profession-

als was as successful as intended.

This study provided examples wherein the acqui-

sition of practical knowledge required an understand-

ing of the tasks. For example, the Path for cesarean

section contained the task of “understanding of the

severity of pain,” which was modeled to be included

in the task of “understanding of organ dysfunction”

and a task of “detection of abnormalities in the oper-

ative site.” However, there was an instruction to ex-

cluding the task of “understanding of organ dysfunc-

tion.” According to the reason, the pain described in

the task “understanding of the severity of pain” indi-

cated wound pain and was not related to the organs.

When asked more specifically, the answer obtained

was: “the result of the detection of abnormalities in

the surgical wound site has been described as wound

pain in the medical record. Based upon the result, it

is decided whether or not an analgesic is prescribed.

Therefore, the description has been corrected to de-

scribe the task flow, and the task of ’understanding of

organ dysfunction’ has not been included in the task

flow.” In addition, there was another answer, “we ob-

serve them thinking about two such possibilities in de-

tection of abnormalities in the surgical wound site.”

Here, we have to focus on the medical task that

is performed while thinking about the two possibil-

ities in “detection of abnormalities in the surgical

wound site.” However, when questioned about prac-

tical knowledge as a task of “understanding of organ

dysfunction,” the respondents stated it was different

from their understanding of the medical service, and

did not talk about their practical knowledge. On the

other hand, when questioned about practical knowl-

edge as a task of “detection of abnormalities in the

surgical wound site,” the respondents talked about

their practical knowledge. This phenomenon sug-

gests that medical professionals relate their practical

knowledge to their understanding of service, and that

their understanding of service should be taken into

consideration when acquiring practical knowledge on

a service.

5.2 Trial Use of Practical Knowledge

A trial use of practical knowledge was conducted

to determine whether there was any inadequacy or

underlying problems in the practical knowledge ac-

quired in terms of descriptions and questions about

the understanding of service during an operation.

5.2.1 Trial Method

• Venue: Five clinical departments (obstetrics and

gynecology, urology, radiology, second depart-

ment of surgery, and pediatrics

• Path: Cesarean section, transurethral resection of

a bladder tumor (TUR-BT), intake of iodine, hep-

atic arterial infusion chemotherapy, renal biopsy

in a child

• Trial period: November 10, 2008 - January 15,

2009 (*the knowledge has been continuously

used)

• Date of interview: Latter part of January 2009

5.2.2 Impressions and Findings after the Trial

We received replies from medical professionals that

there were no inadequacies in the descriptions on the

relation between medical tasks and the understand-

ing of service and the content of practical knowledge.

Their impressions after the trial included: “I could ex-

plain to patients showing them evidence,” “it is easy

to give instructions and explain things to patients us-

ing a uniform presentation,” and “newly hired staff

and shift workers also understand the intentions of

the tasks,” which were generally positive impressions.

After the trial, the practical knowledge has been con-

tinuously used in the hospital. However, there were

some negative opinions about the template of the de-

scriptions, such as “the descriptions are complicated

and unnatural,” and a request that medical profession-

als needed individual presentation according to their

experience.

KEOD 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

128

5.3 Future Subjects

The practical knowledgeon medical services acquired

through the operation was generally accepted, which

suggested that it might have some usefulness. Fur-

thermore, as described in 5.13, attention should be

paid first to the understanding of service by medical

professionals for the acquisition of practical knowl-

edge. However, in order to realize this, we note that

the understanding of service should be modeled from

different points of medical logic and actual medical

practice, as mentioned in 5.12. This suggests a direc-

tion of greater functionality of the modeling, but the

implementation may make the modeling more com-

plicated. Greater functionality should be advanced

according to the level of ontology literacy of the users.

Medical service ontology as used in this paper is

a form of ontology to express the understanding of

medical service as a model depending on the structure

of medical tasks and their medical purpose, and an

ontology constructed in the early phase is the frame-

work. Basically, medical professionals add their con-

cepts to the early ontology, which can then be ap-

plied to other medical institutions. Currently, how-

ever, only five Paths, that were tested in the system

used at the Hospital, have been used. We intend to

conduct a future study in which we will classify the

ontology established by the modeling into one with a

strong field dependency, and one with high general-

purpose properties and degree of reusability, and ar-

range them as guidelines for the construction of an

ontology to ensure interoperability with a model be-

yond the relation among the clinical departments in

a hospital and among hospitals. In medical ontolo-

gies, the concepts of the medical tasks included in

Path can be comprehensively arranged to some extent

based upon medical dictionaries, while the concepts

of tasks that are not included in Path need to be re-

viewed in more detail and in consultation with the re-

sults of studies such as the field of medical diagnosis.

The vision at the root of this study is that individual-

ity by clinical settings should be respected, and that

a special methodology to construct and use a medical

ontology is needed. In view of such a theory for the

construction of an ontology, there are some quite in-

teresting points of views, for example, what the level

of medical purposes is: to what degree is actual medi-

cal service—not medical logic—recognized; and how

much does this recognition differ by occupation or

hospital. We will collect as many modeling cases as

possible in order to obtain sufficient findings.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper introduced a method of using an ontology-

based information support system for the acquisition

and sharing of information in a clinical setting (prac-

tical knowledge) when a patient-oriented service is

performed. It is difficult to comprehensively system-

atize ontology based upon service modeling to ex-

press medical professionalsf understanding of service

in terms of the operationof the system, and it was con-

firmed that the practical knowledge of medical profes-

sionals and the understanding of service were closely

related—according to the results of interviews con-

ducted to acquire practical knowledge. We consider

that the results of this study show that the acquisition

of practical knowledge should be ontologized, as well

as expressing the understanding of service by medi-

cal professionals (what do they think and what values

do they provide to patients through the medical tasks)

support the contention of this study.

A future study will focus on such challenges as de-

vising a method to systematize an ontology, a method

to eliminate intra-sender conflict during the process of

compilation, and a function to support the elimination

of conflict by promotingusage of the system. The sys-

tem described in this paper provides a framework to

express the understanding of service by medical pro-

fessionals. In addition to the framework, a function

to guide procedures for expressions and a supporting

function to check whether there is any imperfection in

the model are required. To implement these functions,

not only was a modeling of the understanding of ser-

vice as the result of thinking investigated, but also an

approximate modeling technique of the thinking pro-

cess, such as assumption of patients to be treated and

problems in the assumption, have been investigated.

Also, a close relation with the electronic health record

needs to be achieved by obtaining access to medical

dictionaries. We will study a method of connecting to

the to ontology in light of a discussion about the con-

cept level of disease and pathology (Mizoguchi and

et al., 2009) (Ohe, 2010).

REFERENCES

Abidi, S. (2009). Towards the merging of multiple clinical

protocols and guidelines via ontology-driven model-

ing. 5651:81–85.

Bennett, J. (1985). Roget: A knowledge-based system for

acquiring the conceptual structure of diagnostic expert

system. 1:49–74.

Boxwala, A. and et al. (2004). Glif3: a representation for-

mat for sharable computer-interpretable clinical prac-

tice guidelines. 37(3):147–161.

ACQUISITION OF SERVICE PRACTICAL KNOWLEDGE BASED ON ONTOLOGIZED MEDICAL WORKFLOW

129

Chandrasekaran, B. (1986). High-level building blocks for

expert system design. 1(3):23–30.

Clancey, W. (1983). The epistemology of a rule-based ex-

pert system: A framework for explanation. 20(3):215–

251.

Coffey, R. (2005). An introduction to critical paths.

14(1):46–55.

Fukushima, H., editor (2004). Changes Medical Record!

Definitive Edition Clinical Path (in Japanese). Igaku

Shoin Ltd., Tokyo.

Gennari, J., Musen, M., and et al. (2003). The evolution

of prot´eg´e: An environment for knowledge-based sys-

tems development. 58(1):89–123.

Hasida, K. (2007). Semantic authoring and semantic com-

puting. 3609:137–149.

Hurley, K. and Abidi, S. (2007). Ontology engineering to

model clinical pathways: Towards the computeriza-

tion and execution of clinical pathways. In Proc. in

20th IEEE Symposium on Computer-Based Medical

Systems. IEEE Press.

Kato, K. and et al. (2005). An empirical study on nursing

activity using critical paths (in japanese). 8.

Kawaguchi, A., Mizoguchi, R., and Kakusho, O. (1989).

A shell for interview systems : Sis (in japanese).

4(4):441–420.

Mizoguchi, R. and et al. (1995). Task ontology for reuse of

problem solving knowledge. 4(4):46–59.

Mizoguchi, R. and et al. (2009). An advanced clinical ontol-

ogy. In Proc. of International Conference on Biomed-

ical Ontology (ICBO), pages 119–122.

Musen, M. and et al. (2006). Clinical decision-support sys-

tems. pages 689–736.

Myers, J. and et al. (1982). Caduceus: A computerized

diagnostic consultation system in internal medicine.

In Proc of Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care, pages

44–47.

Ohe, K. (2010). Standardization of disease names and

development of an advanced clinical ontology (in

japanese). 52(12):701–709.

Schreiber, G. and et al. (2000). Knowledge Engineering

and Management : The CommonKADS Methodology.

MIT Press.

Sutton, D. and Fox, J. (2003). The syntax and seman-

tics of the proforma guideline modeling language.

10(5):433–443.

Tachikawa, K. and Abe, T. (2005). Standardization and

Quality Improvement of Medical Practice by Clinical

Path (in Japanese). Igakushoin Ltd.

Tijerino, Y. and et al. (1993). Methodology for building

expert systems based on task ontology and reuse of

knowledge. 8(4):476–487.

Tu, S. and et al. (2007). The sage guideline model :

Achievements and overview. 14(5):589–598.

Tu, S. and Musen, M. (2001). Modeling data and knowl-

edge in the eon guideline architecture. 84:280–284.

Weiss, S. and et al. (1977). A mode-based consultation sys-

tem for the long-term management of glaucoma. In

Proc. of the 5th international joint conference on Ar-

tificial intelligence, volume 2, pages 829–832.

Yoshikawa, H. (2008). Introduction of service science (in

japanese). 23(6):714–720.

Yoshitake, K. (2007). Medical Ethics and Consensus De-

velopment - Decision Making in the Clinical Settings

- (in Japanese). Toshindo Publishing Co. Ltd.

KEOD 2011 - International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Ontology Development

130