WHY DOES SOCIAL CONTEXT MATTER?

Integrating Innovative Technologies with Best Practice Models for Public and

Behavioral Health Promotion

Luba Botcheva and Shobana Raghupathy

Sociometrics Corporation, Los Altos, California, U.S.A.

{lbotcheva, shobana}@socio.com

Keywords: Technology, Innovation, Acceptance, Integration, Adoption, Behaviour, Change, Health, Social context.

Abstract: In this paper we will present a framework that is intended to guide synthesis of different theoretical

perspectives for the purpose of developing strategies for integrating IT use in diverse social settings. First,

we will briefly review existing theoretical models grounded in behavioural science; and present our

company’s approach for development of products using technology innovation that take in account the

individual, organizational and contextual community characteristics. Secondly, we will illustrate this

approach with three case study examples in the fields of public/behavioral health and education. Finally, we

will conclude with theoretical and practical considerations that can be used by IT developers to maximize

adoption and implementation of innovative technologies.

1 INTRODUCTION

It is universally acknowledged that information and

communication technologies (ICTs or IT) hold huge

potential for enhancing the effectiveness of services

in different sectors. Their ability to reach new

populations, improve communications, and

transform service delivery can increase the

effectiveness and social impact of private, public

and non-profit initiatives. Yet, the positive effects of

innovative IT will only be fully realized if, and

when, they are widely spread and used. It is a well-

accepted fact that the existence of technology does

not guarantee its utilization. Attempts to promote the

adoption and diffusion of innovative IT have often

failed due to a lack of understanding of the factors

that affect acceptance and use of technology by

individuals and organizations. A notable example is

the recent failure of the One Laptop Per Child

(OLPC) project, which aimed to distribute millions

of $100 laptops to disadvantaged school children but

failed to anticipate the social and institutional

problems that could arise in trying to diffuse

technology in the developing country context

(Kraemer, Dedrick, & Sharma, 2009).

As the OLPC case demonstrates, investigating

social context is vital to understanding the

acceptance and use of technologies. Researchers

have often addressed the issue of why individuals

and organizations who would benefit from

technological systems do not use them but

traditionally most of the research has focused on

technological factors and has rarely been applicable

to different sectors and social contexts (Al-Gahtani,

2008). With the rapid utilization of IT in different

spheres of life and across geographical and

economic dimensions, best practice models have

shifted focus to the potential adopter and the

organization or community into which the

technology will be integrated. An adopter based,

instrumentalist approach incorporating both macro-

and micro-level perspectives now appears to be the

most widely used to promote the adoption and

diffusion of innovative ITs.

However, a gap exists between these best

practice models and IT adoption strategies. In

particular, the non-profit and public sectors as a

whole lag behind the private sector in the adoption

of technologies. There has been little scholarly

research into the IT adoption in the non-profit and

public sectors. This paper discusses ways that

technology acceptance models can be utilized to

develop multi-level approaches for facilitating IT

adoption in diverse social settings (educational,

health and community-based organizations) with

special emphasis of the contextual characteristics

that determine the success of this process.

151

Botcheva L. and Raghupathy S.

WHY DOES SOCIAL CONTEXT MATTER?Integrating Innovative Technologies with Best Practice Models for Public and Behavioral Health Promotion.

DOI: 10.5220/0004459701510157

In Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2011), pages 151-157

ISBN: 978-989-8425-68-3

Copyright

c

2011 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

2 BEST PRACTICE IN

TECHNOLOGY ADOPTION

2.1 Existing Theoretical Models

A rich body of literature has emerged that employs

behavioural science theories to model factors

affecting the acceptance and use of technology at

both the individual level and the organizational

level. Prominent examples include the Technology

acceptance model (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw,

1989), Theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1985),

Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology

(Venkatesh, Morris, Gordon B. Davis, & Davis,

2003), Diffusion of innovation (Rogers, 1995), and

the Technology, organization, and environment

framework (Tornatzky and Fleischer 1990). Some of

these models focus on technological and individual

factors influencing acceptance but as models have

become more sophisticated and better validated,

there has been an increasing acknowledgement of

the centrality of environmental and contextual

constructs. Key constucts in these models that relate

to contextual factors include compatability (with

existing technology, work practices, beliefs and

values), social influence, professional environment,

organizational structure. In addition, many of the

models discuss individual factors that are inevitably

related to broader environmental and social contexts,

such as attitudes, beliefs and subjective norms. A

comparison of theories of change and contextual

constructs defined in models of technology

acceptance is presented in the Appendix.

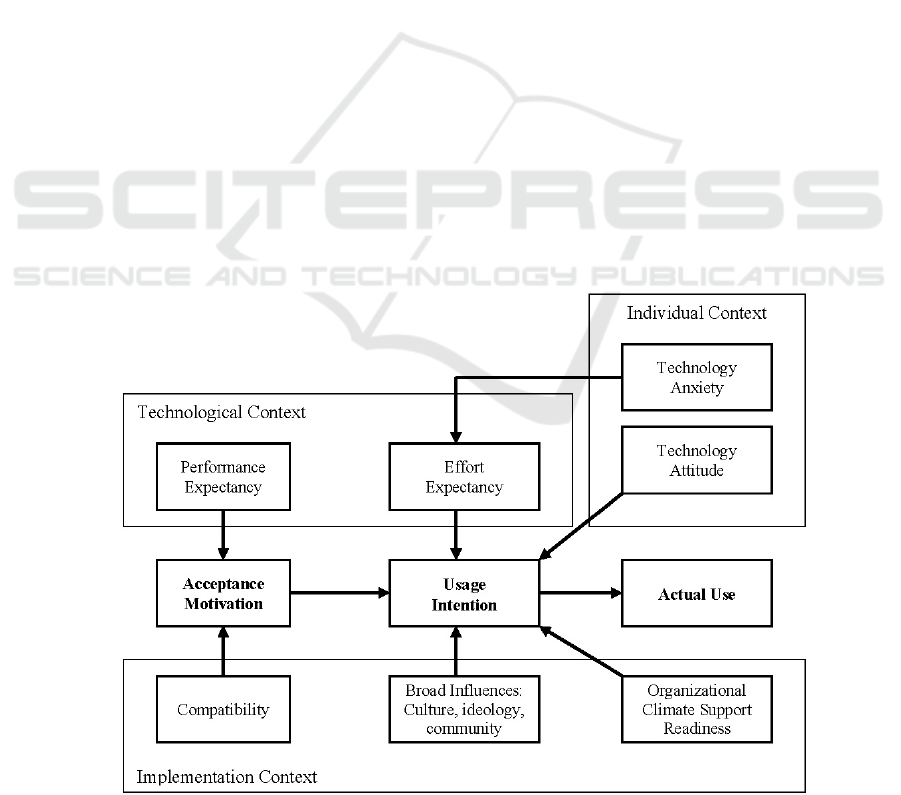

Drawing from these theories we present a revised

multi-contextual model, adapted from the extended

technology acceptance model (Dadayan & Ferro,

2005) to incorporate broad social influences such as

culture, community context, and ideologies that are

critical for technology adoption in real life contexts

(see Figure 1).

• Individual context refers to the characteristics of

individual end-users and their attitudes to

technology;

• Technological context refers to the characteristics

of the technology such as functionality and user-

friendliness; and

• Implementation context refers to the user’s

environment, including organizational factors

(climate, support, readiness); broad social influences

(community, culture, ideologies); and technology

compatibility.

In the next sections drawing on the extensive

experience of our company in developing innovative

products for public and behavioural health

promotion, we will outline the methodology that we

use to examine these different characteristics for

developing technology products that are adequately

integrated within real-life contexts.

Figure 1: Revised Multi-contextual Model of Technology Acceptance.

BMSD 2011 - First International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

152

2.2 Our Approach: The Intersection

Between Research, Technology

and User Needs

Established in 1983 and selected as an exemplary

small business in 2007 by the National Academy of

Sciences, Sociometrics’ primary mission is to

develop and disseminate behavioural and social

science research-based resources for a variety of

audiences in order to: 1) promote healthy

behaviours; and 2) prevent or reduce behaviours that

put an individual’s health

and well-being at risk.

During the last ten years, Sociometrics’ staff has

developed engaging IT public and behavioural

health promotion products and has also accrued

significant experience developing and disseminating

research-based materials tailored for diverse target

audiences through large scale websites, digitalized

effective program materials, data libraries, and

evaluation and training e-tools (see full description

at www.socio.com).

All products are developed based on a thorough

examination of user needs and preferences with a

special attention to the contexts in which they will

be implemented to assure their acceptance and

relevance.

3 CASE STUDIES

3.1 e-Learning Products for Early

Intervention Professionals

In this case example we present the process of deve-

loping interactive program tutorials tailored to the

different learning styles of early intervention

professionals working in diverse settings (child care

centres, hospitals, and community-based centres).

The project was part of a Sociometrics initiative

funded by NIH aimed at assembling in one place—

for public dissemination, distribution, and

replication—treatment programs in the area of early

childhood intervention. One of the important goals

of the project was to design technology assisted

professional tutorial materials to assist early

childhood professionals to implement programs with

fidelity in their professional settings. Following the

principles of Dabbagh and Bannan-Ritland (2005)

for on-line learning design, we first identified users’

characteristics and learning styles and then explored

their learning and professional context. Using

interviews with potential users, observations of their

professional context and reviews of relevant

literature we were able to outline contextual

characteristics that determined the design and

technological modality of the professional tutorials

(see Table 1).

3.1.1 Individual Context

The analysis of the individual context showed that

technology based products are not used routinely by

potential users, which determined relatively high

technology anxiety; attitudes to technology vary

among professionals with medical and

administrative personnel being more positive. In

response to this context we decided to create

learning tools that are easy to use by people with no

previous experience with technology.

Table 1: Context analysis for developing early childhood intervention professional tools.

Context

Early Childhood Intervention Contextual

Characteristics

Solutions

Individual Context

Technology anxiety

Technology attitudes

Technology anxiety relatively high

Attitudes vary among professionals

but in most cases technology based

products are not used routinely

Create learning tools that are easy

to use by people with no previous

experience with technology

Technological Context

Performance expectancy

Effort Expectancy

Performance expectancy is high;

users will not use these tools if they do not

believe that they will improve their direct

work

Based on the high work load and

relative low level of technology skills, the

effort expectancy is for easy use

Constructivist approach– learning

by doing, e.g., cognitive apprenticeships,

situated learning, problem-based learning,

efficient learning (minimizes tangential

activity)

Practical (product of instruction is

useful for everyday activity)

Implementation context

Compatibility with existing

technical systems

Organizational support

Professional culture

Technical system limited to basic

software

Technology support often is scarce

Resistance to change; conservative

organizational climates

System that is compatible with

basic software

Materials that will not require a lot

of additional support

Adaptable to diverse learners’

styles and contexts

WHY DOES SOCIAL CONTEXT MATTER? - Integrating Innovative Technologies with Best Practice Models for Public

and Behavioral Health Promotion

153

3.1.2 Technological Context

The technological context analysis showed that

performance expectancy is high; users will not use

these tools if they do not believe that they will

improve their direct work; based on the high work

load and relative low level of technology skills the

effort expectancy is for easy use. To match these

expectations we selected a constructivist approach

for the pedagogical design of the products that is

efficient and practical.

3.1.3 Implementation Context

We analysed several aspects of the implementation

context: 1) compatibility with existing technological

systems: most of the technical systems used by our

users were limited to basic software, which meant

that the professional tools should utilize basic

software that is widely available; 2) Professional

culture; most of the professionals worked in the non-

profit sector, either at health or educational

environments that have been shown to be relatively

conservative and resistant to change (Botcheva et

al.2003): thus the use of our tools should not require

a lot of changes in the routine practices; they should

be tailored to different professional environments

and specific learner needs allowing customisation;

3) Organisational support of implementation:

technology support is scarce in most of the

organisations; thus the tools should be easy to

maintain with minimum technical support.

This multi-level analysis led us to the decision to

create e-learning materials using Adobe interactive

PDFs that will include hands on examples and

resources tailored to the different learning styles and

experience of the individual learner. Interactive

PDFs fit seamlessly into the complex pattern of

diverse learners’ needs, constraint and resources. On

the one hand, they are: completely stable; typically

get past firewalls; require no special software/system

other than Adobe Reader; printable, and easy to

maintain. On the other hand, they are: highly

dynamic; allow audio, video, automations;

indexing/bookmarking and easy linking. These

characteristics helped us to create interactive and

engaging e-learning tools that fit the context of and

user characteristics of early childhood professionals.

3.2 Using the Individual, Technological

and Implementation Context to

Design e-Tools for Data Collection

Public schools in the United States are required to

annually collect and report data on drug use and

other high-risk behaviours from elementary, middle

and high school children. All schools receiving

federal and state funding are expected to collect

baseline data for establishing incidence or

prevalence of data on truancy rates, drug and

violence related suspensions and expulsions, drug

incidence, and prevalence rates, and for

demonstrating simple percentage changes in

outcomes for end of the year performance reports.

It is often difficult, however, for schools to

engage in periodic data collection efforts in the light

of budget constraints and time constraints (Mantell,

Vittis, & Auerbach, 1997; Sedivy, 2000). Teachers

are expected to take on responsibilities other than

teaching even at a time when there are increasing

pressures on them to raise students’ academic

achievement levels. Thus, collection and monitoring

of data on substance use or other health concerns are

perceived as consuming valuable time (Hallfors,

Khatapoush, Kadushin, Watson, & Saxe, 2000). In

response to this need, Sociometrics designed a web-

based survey development and analysis tool that

would allow for swift, efficient and most

importantly, cost-effective data collection, analysis

and reporting. The online system would allow

students to login to a pre-programmed survey with

measures on drug use patterns, truancy and other

high risk behaviours; answer the survey questions;

then logout once he or she is finished. The survey

data would automatically be deposited in a secure

web server and can be accessed by the teacher for

analysis. Such an e-tool is cost effective as it

automates the survey creation and administration

process, and relieves the teacher of burdensome

tasks such as printing surveys, distributing them and

then entering and processing the data.

In designing such a tool, we first started with a

needs assessment that took account of the larger

operational context: specifically, we investigated the

wide range of constraints, limitations and facilitating

factors at the individual (teacher), technological

(school infrastructure), and implementation context

(school). We first identified the primary consumers

of the product. These included not just school

teachers and principals who were responsible for the

data collection and reporting, but also district and

state level supervisors at the State Department for

Education who were responsible for school funding

allocations and monitored school progress. Next, we

conducted numerous focus groups and interviews

with the target audience. The qualitative studies

yielded useful insights into current data collection

efforts in schools, and offered valuable design,

BMSD 2011 - First International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

154

content and dissemination guidelines for our e-tool.

Some of these insights are outlined below.

3.2.1 Individual Context

Teachers began their data collection efforts by

selecting measures, creating paper and pencil

surveys, and administering the surveys in the

classroom during recess, after school hours or

whenever possible, during a health education class.

The data were coded and entered by hand and then

reported to the district. The schools had to provide

districts with end of the year “performance reports”

which reported simple changes in drug and violence

incidents over the school year as part of their

assessment. Numerous problems with the process

were reported, such as insufficient funding and time,

as well as lack of technical assistance. Those in the

poorly funded districts mentioned high student

movement and attrition, and problems in tracking

students. Teachers complained about the time and

effort involved in tracking such data and preparing

reports. They also complained about not receiving

any form of technical assistance from their districts

in terms of selecting appropriate measures. Many

teachers lacked the capacity to conduct basic

statistical analysis such as means, and percentage

changes in key behavioural indicators. It therefore

became clear to us that any online data collection

tool would need to pre-program measures and

indicators that were popular, reliable and validated.

We conducted a poll of the most popularly used

measures and indicators for capturing school

performance and developed pre-programmed

surveys incorporating such indicators. A basic

statistical tool was developed that would allow

teachers to derive summary statistics such as means

and frequencies (e.g. no: of student arrests on drug

related charges, percentage of boys and girls referred

to treatment services etc) without having download

data or use any external software such as SPSS.

(Teachers were also given the option to download

the data if they desired). Finally, it became clear that

because of time and capacity limitations, an

interface needed to be created that would allow

students to take the survey from multiple locations,

and over different points in time. This realization led

not only in interface design changes, but also the

format and structure in how data were to be stored.

3.2.2 Technological Context

One major concern that emerged was whether the

introduction of a new, online data collection system

would introduce a steep “learning curve” for

teachers. Another concern was related to the

investments that the school would be required to

undertake in order to adopt it. To emphasize the

utility and user-friendliness of the e-tool, we decided

to present our product concept in images and terms

that were already familiar to the groups. For

example, we used an existing online survey

system—SurveyMonkey—to illustrate our e-tool

and the precise manner in which it would different

and specially tailored for their school needs. Some

of the school teachers in the focus group were

already using online teacher evaluations: we

encouraged them to speak to the group about their

experiences (both positive and negative), and

highlighted how our product would attempt to

overcome the limitations and replicate the successes

of their experience. By the end of our needs

assessment, teachers and administrators were by and

large, receptive to the idea of online data collection

indicating that our strategies for reducing

“technology anxiety” and establishing “performance

expectancy” were successful.

3.2.3 Implementation Context

During the design and product development stage of

any school-based e-tool, it is absolutely essential to

ensure its compatibility with the school’s

technological infrastructure. A technology

“screener” was mailed out to the focus group

participants and interviewee’s participants in order

to assess the basic “minimum” technological

capacity that the e-tool would have to be compatible

with. Questions included: number of computers in

the school, Internet access, and bandwidth etc.

While almost all schools in our focus group had

Internet access, it became clear that lack of access to

sufficient computers (along with time constraints)

was yet another feature that necessitated group log-

ins from multiple locations (such as libraries,

computer labs and even homes). Privacy and

confidentiality of student data subsequently emerged

as a concern. As a first step, we designed a single

question interface with autoprogression; the screen

automatically gets refreshed once a question was

answered thereby minimizing the amount of time a

response was present on screen. The interface also

included separate login IDs for students and

administrators. Students could use their IDs to login

from any location that was convenient to them while

the administrator had sole control over the data

collected. Administrators using the online statistical

tool (described earlier) would be able to do so

without accessing individual student data. If the

WHY DOES SOCIAL CONTEXT MATTER? - Integrating Innovative Technologies with Best Practice Models for Public

and Behavioral Health Promotion

155

administrator did choose to download the data, the

downloaded data was made available without subject

identifiers in order to maintain confidentiality.

Besides confidentiality, another concern was

related to product pricing and affordability.

Participants identified “frontline” funding and

decision making agencies and offices at the state,

county and district level that could spearhead the use

of online data collection mechanisms in their

districts. We learned that pursuing business

opportunities with state and district agencies (rather

than individual schools) would allow costs to be

incurred by these agencies and would facilitate large

scale adoption of the technology at the ground level.

4 IMPLICATIONS FOR

DEVELOPERS

There are several theoretical and practical

implications for developers that stem from this

analysis.

First, the review of existing theoretical models of

technology acceptance highlight the importance of

developing multi-dimensional approaches that take

in account different social contexts to fully

understand the processes of technology integration

in real life contexts. Interdisciplinary teams

incorporating the knowledge and skills of

technology developers, social and behavioural

scientists will be best suited to solve this problem.

Second, the analysis of technology acceptance in

the non-profit sector highlights the critical

importance of broad social context, such as culture,

ideology, and community climate.

While in

industry, the transition from research and

development to the field primarily focuses on the

end user, in the non-profit sector, there is a range of

intermediary factors (agencies, policies) that

influence if and how the product reaches the end

user. Thus, conventional theories regarding

technology diffusion and adoption need to be

modified with regard to the non-profit and public

sectors.

Third future research and development effort

should focus on development of practical tools and

screeners that will facilitate the translation of

contextual characteristics into technical

requirements for development of products that can

be easily adopted and integrated in real life contexts.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to thank Katie Boswell and Eileen Moyles

for valuable input to this paper. The research

developments reported in this paper are funded by

National Institute on Deafness and Other

Communication Disorders and National Institute on

Drug Abuse.

REFERENCES

Ajzen, I. (1985). From Intentions to Action: A Theory of

Planned Behavior. Action-Control: From Cognition to

Behavior (pp. 11-39). Springer.

Dabbagh, N., & Bannan-Ritland, B. (2005). Online

learning: concepts, strategies, and application.

Pearson/Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Dadayan, L., & Ferro, E. (2005). When Technology Meets

the Mind: A Comparative Study of the Technology

Acceptance Model. In M. A. Wimmer, R.

Traunmüller, Å. Grönlund, & K. V. Andersen (Eds.),

Electronic Government (Vol. 3591, pp. 137-144).

Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989).

User Acceptance of Computer Technology: A

Comparison of Two Theoretical Models. Management

Science, 35(8), 982-1003.

Hallfors, D., Khatapoush, S., Kadushin, C., Watson, K., &

Saxe, L. (2000). A Comparison of Paper vs.

Computer-Assisted Self Interview for School,

Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drug Surveys.

Evaluation and Program Planning, 23(2), 149-55.

Kraemer, K. L., Dedrick, J., & Sharma, P. (2009). One

laptop per child: vision vs. reality. Communications of

the ACM, 52, 66–73. doi:10.1145/1516046.1516063

Mantell, J. E., Vittis, A. T. D., & Auerbach, M. I. (1997).

Evaluating HIV prevention interventions. New York:

Plenum Press.

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations. Simon and

Schuster.

Sedivy, V. (2000). Is Your Program Ready to Evaluate Its

Effectiveness? A Guide to Program Assessment. Los

Altos, CA: Sociometrics Corporation.

Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Gordon B. Davis, & Davis,

F. D. (2003). User Acceptance of Information

Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Quarterly,

27(3), 425-478.

BMSD 2011 - First International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

156

APPENDIX

Table 2: Comparison of theories of change and key contextual constructs in models of technology acceptance.

Model and authors Theory of change Key constructs related to context

Technology, organization,

and environment (TOE)

framework (Tornatzky and

Fleischer 1990)

At the organizational level, three aspects influence

the process by which an enterprise adopts and

implements a technological innovation:

technological context, organizational context, and

environmental context.

Environmental context is the arena in which a

firm conducts its business—its industry,

market structure, competitive pressures,

technology support infrastructure and

government regulation.

Theory of planned behavior

(TPB) (Ajzen 1985, Ajzen

1991, Bajaj and Nidumolu

1998)

At the individual level, behavior is influenced

solely by behavioral intention and behavioral

intention in turn is influenced by attitudes toward

behavior, by subjective norms and by perceived

behavioral control.

Behavioral intention is influenced by

attitudes, subjective norms and perceived

control but these are not explicitly linked to

broader environmental context.

Diffusion of innovation

(DOI) (Rogers 1995)

At both individual and organizational level,

innovations are communicated through certain

channels over time and within a particular social

system. Diffusion through an organization is

related to individual (leader) characteristics,

internal characteristics of organizational structure,

and external characteristics of the organization.

The external characteristics element of the

model refers to system openness.

Technology acceptance

model (TAM) (Davis 1986,

Davis 1989, Davis et al.

1989)

At the individual level, “perceived usefulness”

(outcome expectation) and “perceived ease of use”

(self-efficacy) influence decisions about how and

when individuals will use a new technology, with

intention to use serving as a mediator of actual use.

External variables may be antecedents or

moderators of perceived usefulness and

perceived ease of use. However, there is an

assumption that when someone forms an

intention to act, that they will be free to act

without limitation.

Multi-contextual technology

acceptance framework (Hu

et al. 1999, Chau and Hu

2002)

At the individual level, technology acceptance

behavior is influenced by factors pertaining to the

individual context, the technological context, and

the implementation context.

“Implementation context” refers to the user’s

professional environment.

Unified theory of acceptance

and use of technology

(UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al.

2003)

At the individual level, technology use is directly

determined by performance expectancy, effort

expectancy, social influence, and facilitating

conditions. The impact of these factors is

moderated by gender, age, experience, and

voluntariness of use.

Social influence refers to the degree to which

an individual perceives that others believe he

or she should use a particular technology.

Facilitating conditions refer to the degree to

which an individual believes that an

organizational and technical infrastructure

exists to support the use of a particular

technology.

Extended technology

acceptance model (Dadayan

and Ferro, 2005)

At the individual level, technology acceptance is

influenced by not only technological factors but

also by the individual context and the

implementation context.

The implementation context includes three

determinants — compatibility, social

influence, and organizational facilitation.

Not-for-profit internet

technology adoption model

(O’Hanlon and Chang 2007)

At the organizational level, technology adoption is

influenced by technical capacity, compatibility

(with the organization’s work practices, beliefs and

values), support (of staff and donors), and

organizational characteristics.

Organisational practices, beliefs and values

are critical for the adoption process.

WHY DOES SOCIAL CONTEXT MATTER? - Integrating Innovative Technologies with Best Practice Models for Public

and Behavioral Health Promotion

157