AGGREGATION OF STAKEHOLDER PREFERENCES

IN SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT USING AHP

C. Maroto

1

, M. Segura

1

, C. Ginestar

1

, J. Uriol

2

and B. Segura

3

1

Department of Applied Statistics, Operations Research and Quality, Universitat Politècnica de València,

Camino de Vera s/n, 46021-Valencia, Spain

2

Department of Rural and Agrifood Engineering, Universitat Politècnica de València,

Camino de Vera s/n, 46021-Valencia, Spain

3

Department of Economics and Social Sciences, Universitat Politècnica de València,

Camino de Vera s/n, 46021-Valencia, Spain

Keywords: Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis, Group Decision Making, Analytic Hierarchy Process, Sustainable

Forest Management.

Abstract: The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is the most often applied approach to modelling strategic forest

management problems. When dealing with Multiple Criteria Decision Making, AHP allows one to take

social, economic and environmental criteria of sustainability concept, as well as public participation, into

account. We carried out a workshop to validate a decision hierarchy for Sustainable Management in

Mediterranean forests, as well as two surveys to elicit social priorities. Stakeholder and expert judgments

were integrated using the geometric mean to obtain group preferences. We applied this method to develop

empirical research into sustainable forest management in a Mediterranean region, where the environmental

and social services of the forest are more important than the economic ones. We quantified weights of

criteria, objectives and management strategy priorities and discuss the obtained results.

1 THE PROBLEM

The environmental problems and decision making in

this area are issues that governments, companies and

citizens are more aware of each day. Over the last

decade, Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) has

emerged as a dominant forest management paradigm

(Ananda, 2007). An accepted definition of SFM is

the following: The management and use of forests

and forest lands in such a manner and at such a rate

that they can maintain their biodiversity,

productivity, regeneration capacity, vitality and the

potential to fulfill, now and in the future, important

ecological, economic and social functions at local,

national and global levels without causing damage to

other ecosystems (Ministerial Conference on the

Protection of Forests in Europe, 1993). This

definition implies the inclusion of environmental,

economic and social criteria in the decision making

at every level, whether strategic, tactical or

operative. This is the reason for using Multiple

Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) tools.

Nowadays public participation is also, in general,

an essential part of sustainable forest management

particularly in Europe. Public participation means

that citizens are involved in decision-making that

has an effect on natural resources. In addition, the

legitimacy of the final decision may be better, when

the different stakeholders are involved in the

decision making (FORSYS, 2011). For this reason,

Group Decision Making (GDM) is also necessary.

However, from the Operations Research field, we

know that the inclusion of the preferences of the

stakeholders in public decision making is not an

easy problem to solve, given the conflict of interests

that usually appears between the stakeholders. The

application of GDM methods in forestry from a

multicriteria perspective is a relatively new area of

research (Diaz-Balteiro and Romero, 2008).

In past decades forest management has been the

source of many problems in decision making,

mainly related to the wood industry (Martell, Gunn

and Weintraub, 1998). For that reason, publications

refer to the principal productive zones: North

America, Latin America, Scandinavia, Australia and

New Zealand. We can state that the situation is still

100

Maroto C., Segura M., Ginestar C., Uriol J. and Segura B..

AGGREGATION OF STAKEHOLDER PREFERENCES IN SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT USING AHP.

DOI: 10.5220/0003697401000107

In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems (ICORES-2012), pages 100-107

ISBN: 978-989-8425-97-3

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

the same, as demonstrated by Ananda and Herath

(2009). In addition, these authors show that

theoretical developments have moved faster than

empirical applications of MCDM.

The Mediterranean forest is one of the more

vulnerable ecosystems (IPCC, 2007) and is one

which plays an essential role as a regulating element

of water resources and climate change, as well as

minimizing advancing of erosion and biodiversity

loss. Nevertheless, we do not see, in the scientific

literature, studies which deal with decision making

at a regional level, the inclusion of public

participation and the concept of sustainability in

forest management. In regional planning, the works

of Ananda (2007) and Ananda and Herath (2008)

presented a real application integrating MCDM and

GDM approaches in the North East Victoria region

(Australia). In Europe, studies concentrate on

specific, limited, areas (Diaz-Balteiro, González-

Pachón, J. and Romero, C., 2009; Nordström, E.M.,

Romero, C., Eriksson, L.O. and Öhman, K., 2009;

Nordström, E.M.; Eriksson, L.O. and Öhman, K.,

2010).

The objective of this study is to develop a model

for the sustainable forest management at a regional

level for the Mediterranean forest that takes public

participation into account as well as the relevant

objectives, integrating both aspects to inform public

policies, using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP).

We have organized the paper as follows: In

section 2 we present the most relevant data of the

Valencian Community forest, the decision making

hierarchy that we have developed, as well as the

process for validating it with the stakeholders and

elicit their preferences. In section 3 we explain how

we aggregate the preferences and expert knowledge

through geometric mean. Following that, we present

the results about criteria, objectives and strategies of

management. Finally we highlight the conclusions

and the future lines of research.

2 METHODOLOGY:

STAKEHOLDERS, DECISION

HIERARCHY, WORKSHOP

AND SURVEYS

2.1 Mediterranean Forests in

Valencian Community and Forest

Stakeholders

The Valencian Community is located on the

Mediterranean coast of Spain. It is an Autonomous

Region of the Spanish State with its own authority

for strategic forest management. Nowadays, the

relevance of the Mediterranean forest is mainly due

to the services that it provides and not to the

traditional production of wood and cattle where its

productivity is very low compared when to the

Atlantic forest, characteristic of the North of Spain

and Europe. The Valencian forest surface, covers

almost 60% of the territory, but contributes barely

0.03% of the GNP. The Valencian Community has a

total forest area of 1,323,465 hectares (PATFOR,

2011) and 4.5 million people, a population density

higher than the European Union average.

The regional government annually distributes an

important quantity of money amongst different lines

of action, dedicating as much to private as to public

forest. In 2010, the budget was more than 147

million Euros of which more than 70% was spent on

fire prevention and extinction, mostly the latter. The

public forest is approximately one third of the total

and is mainly managed by the forestry

administration.

Several authors consider that MCDM must adopt

a more participatory posture at all levels of the

modeling process. Stakeholders must be able to

participate and contribute actively to modeling

(Mendoza and Martins, 2006). The main role of

stakeholders in sustainable forest management has

also been highlighted in other recent studies which

focused on regional forest programs in Finland

(Kangas et al, 2010).

In our case, we have identified the following

stakeholder groups in the Valencian Community:

Administration, Professional Engineering

Associations, people involved in Forest Research

and Education, Hunting and Fishing Federations,

Forest Owners (private owners and municipalities),

Companies and Land Stewardship, Environmentalist

and Conservationist Groups. Representatives of

these groups are the ones previously invited by the

Regional Government to collaborate in developing

new forest programmes in the Valencian

Community.

2.2 Decision Hierarchy and Workshop

In developing our value tree or decision hierarchy

we tried to construct the simplest possible model,

while taking into account several other important

considerations. We tried to balance completeness

(wherein all important aspects of the problem are

captured) with conciseness (keeping the level of

detail to a minimum), two conflicting requirements

in defining criteria and objectives for our problem.

Another important characteristic of the work as an

AGGREGATION OF STAKEHOLDER PREFERENCES IN SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT USING AHP

101

operational model is to take into account that the

volume of information and the demands on the

people involved should not be excessive (Belton and

Stewart, 2003).

We organized an all day workshop (April 2010)

with representatives of all stakeholder groups to test

the criteria, objectives and management strategies

we had proposed and previously discussed with

several experts. In this workshop, with almost 200

participants, we carried out a round table with

stakeholder’s representatives, followed by a

colloquium and general debate between all

participants. We had previously presented principal

statistical data on Valencian forests and maps with

public and private forest areas, as well as the

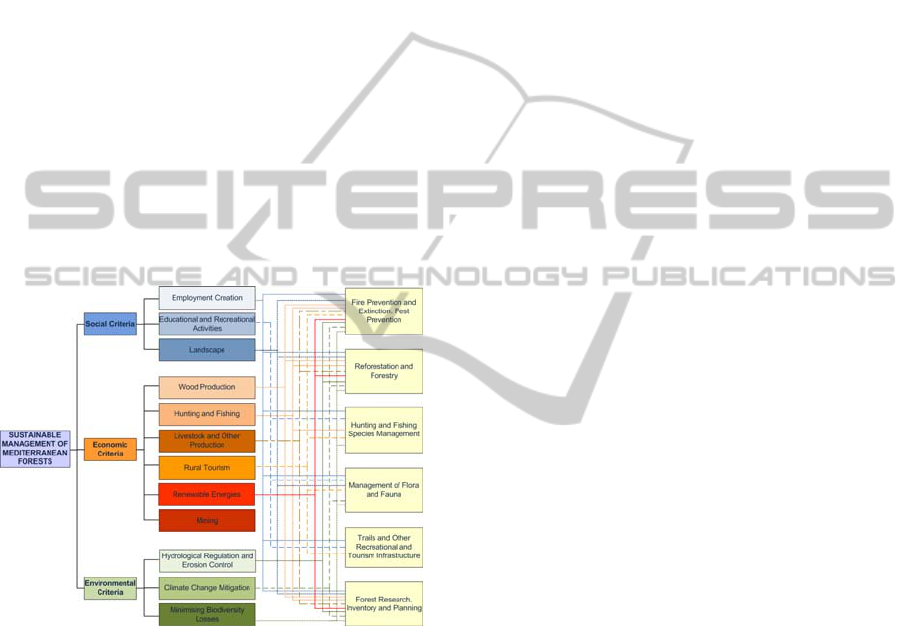

decision hierarchy. Figure 1 synthesizes the goal, the

criteria, the objectives and the management

strategies, finally adopted after this workshop.

Group participation with knowledgeable people is a

good way to ensure that the decision hierarchy is a

logical and complete structure (Saaty and Shih,

2009).

Figure 1: Decision hierarchy for Sustainable Management

of Mediterranean Forests.

The lowest level of the decision hierarchy is for

management strategies at regional level:

1. Fire prevention and extinction. Pest prevention.

2. Reforestation and forestry.

3. Hunting and fishing species management.

4. Management of flora and fauna.

5. Trails and others recreational and tourism

infrastructure.

6. Forest research, inventory and planning.

The model represented in Figure 1 intends to be

a strategic model for the public administration to

inform sustainable forest management, both public

and private, at a regional level. For this reason it has

been structured with the same objectives for all

stakeholders. We consider that this is the proper

structure for a regional model which can be used as

a general framework for small scale planning, such

as, demarcation, regional, municipal or areas such as

protected natural parks, etc. This differentiates the

model from those which focus on a specific piece of

forest, such as the one developed for an urban forest

in Nordström et al. (2009), in which each group of

stakeholders has different interests and it is not

possible to define a structure that everybody accepts.

2.3 Surveys, Questionnaires and

Matrix Consistency

In the three first levels of figure 1, the stakeholders

might have a different opinion, for example, in the

importance that the social criteria might have in the

sustainable forest management. Thus, some might

assign greater importance to social criteria, other

might emphasize the environment and the owners

would probably be more interested in economic

objectives. We can see that whether we consider that

job creation or the landscape is the attribute which

contributes more to the social criteria is a subjective

question. After accepting the hierarchical structure

of the model, the participation of the stakeholders

consists in defining their preferences for the first

three levels. With this objective we made a first

survey of the representatives of all the 7 groups of

stakeholders considered.

In the workshop we explained Saaty´s basic scale

of comparisons between pairs of criteria with the

objective that stakeholders could respond to a

questionnaire. We carried out a first survey to elicit

the preferences of stakeholder groups for criteria and

objectives. 46 stakeholders generated 5 pairwise

comparison matrices each, where each element in an

upper level is used to compare the elements in the

level immediately below with respect to it (Saaty,

2006). We obtained 2 matrices that contain the

preferences of each person surveyed on the

contribution of the social, economic and

environmental criteria to the sustainable

management of the Mediterranean forest. One

matrix refers to all forests of the region and another

specifically for public forest. The other 3 matrices

refer to the contribution of the third level objectives

to the criteria of the second level (social, economic

and environmental). We asked the stakeholders to

complete the top half of the comparison matrix and

we assumed a reciprocal matrix.

The contribution of the strategies from the lowest

level of the hierarchy to the objectives from the third

ICORES 2012 - 1st International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

102

level is not a subjective question of stakeholder

preferences rather it is a technical matter. The lack

of data about the contribution of each strategy to

each objective lead us to propose a second survey

using the same methodology as in the first one, but

this time consulting only the experts who

participated in the first survey. We have grouped the

alternatives in six categories, due to the

methodology of pairwise comparison. A greater

number of strategies would imply a greater number

of questions and thus less consistency in the

resulting matrices. In this second phase we obtained

17 completed questionnaires, with 11 matrices in

each one, and their distribution amongst the groups

of forestry experts is as shown in table 1. As the

mining activity does not receive public money from

the forest administration it is not necessary to obtain

a matrix for this objective. Nevertheless, we have

considered it necessary to include it explicitly in the

model given that it economically benefits the

owners.

We have analyzed the consistency of the answers

to both surveys with SuperDecisions Software

(2010) and we have only taken into consideration

those that have an Inconsistency Index less than or

equal to 0.1, which is considered acceptable when

using AHP (Saaty, 2006). The percentage of

matrices with an Inconsistency Index less than or

equal to 0.1 in the first survey is 67% when

stakeholders compare 3 criteria and 50% when 6

criteria were involved in pair comparisons.

Inconsistencies are not unexpected, as making value

judgments is difficult (Keeney, 2002).

Table 1: Distribution of questionnaires among stakeholder

groups (first survey) and expert group (second survey).

Stakeholder Groups

Number of questionnaires

First survey Second survey

Administration 17 9

Professional Engineering

Associations

5 3

Forest research and education 8 3

Hunting and fishing

federations

3 -

Forest owners 4 -

Forestry companies 6 2

Land stewardship,

environmentalist and

conservationist groups

3 -

TOTAL 46 17

The second questionnaire was conducted

amongst the experts that had answered the first

survey consistently. The consistency of these

matrices is greater than in the first questionnaire and

does not depend so much on the number of strategies

to be compared. The percentage of consistent

matrices has been between 71 and 82% with 3, 4, 5

and 6 strategies to compare. Only in climate change

(65%) and renewable energies (53%) did the

percentage decrease, which would seem to be related

to the newness of these criteria.

3 AGGREGATION OF

PREFERENCES USING

GEOMETRIC MEAN

The weighted geometric mean is the most common

group preference aggregation method in the AHP

literature. If judgment matrices M

1

, M

2

,..., M

n

given

by stakeholders or experts are of perfect consistency,

then their group consensus matrix is of perfect

consistency. In addition, the consensus matrix is of

acceptable consistency (Inconsistency Index ≤ 0.1)

on the condition that each individual matrix is of

acceptable consistency (Xu, 2000).

Figure 2: Aggregation of individual preferences to obtain

group consensus matrix and weight vector.

In Figure 2 we can see the procedure for

integrating the values R

i

jk

of the individual

stakeholder matrices into the values R

C

jk

of the

consensus matrix for each group. As we only use

matrices of an acceptable consistency in the AHP

method, the consensus matrices that represent the

preferences of the group have been obtained by the

geometric mean and also have an acceptable

consistency. We consider that all people are equally

important. The priorities that reflect those

preferences are the values of the eigenvector,

obtained using SuperDecisions software (Saaty and

Peniwati, 2008). We have used this procedure to

obtain the priorities that each group of stakeholders

gives to the criteria and objectives considered in the

AGGREGATION OF STAKEHOLDER PREFERENCES IN SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT USING AHP

103

model, as well as to synthesize the knowledge of the

experts in the second survey. In this last case the

synthesis of the opinions of all the experts allow us

to estimate how much each management strategy

contributes to each of the considered objectives. We

should emphasize that in the survey we highlighted

that the comparison between each pair of strategies

supposes that we spend the same amount of money

on each of them.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Preferences of Stakeholder about

Criteria and Objectives

All the experts have traditionally assigned great

importance to the multiple functionality of the

forest. Nevertheless, the best way of integrating this

characteristic into strategic management at a

regional level, taking into account the preferences of

the stakeholders, is a complex decision making

problem. Nowadays, we should also add that the

concept and measurement of forest sustainability is

still an open problem (Diaz-Balteiro and Romero,

2008). We have to start by quantifying the weight

that society wishes to assign to the three basic

criteria of the SFM and the attributes from the ones

we measure. In this section we present the main

results obtained in our first survey to learn the

preferences of all of the groups of stakeholders and

of society as a whole.

Figure 3 shows that, in general, the most

important criteria is the environmental one except

for some of the groups that represent economic

interests, such as land owners and forestry

companies, for whom the economical criteria are the

most relevant. The associations of forest engineers

give the greatest weight to social criteria, as do as

the Land Stewardship, Environmentalist and

Conservationist Group (LSEC group), even though

we will later see that this is due to different

objectives. We also want to highlight the low weight

of economic criteria for all of the groups in general

and for forestry administration in particular.

In Figure 4 we can observe the relative weights

of the different criteria, referred only in this case to

public forest. The public forest represents one third

of the forestry surface and the majority of it is

managed by the forestry administration. The relative

weights are very similar to those obtained for all of

the forests in general. Nevertheless, the importance

of environmental criteria rises slightly in the public

forest for the priorities of the administration, the

land owners, the companies and the LSEC group.

Something similar occurs with social criteria, while

the economic criteria have even less importance.

Figure 3: Priorities of social, economic and environmental

criteria in sustainable management of Valencian Forest by

stakeholder groups.

Figure 4: Priorities of social, economic and environmental

criteria in sustainable management of Valencian Public

Forest by stakeholder groups.

The distribution of the preferences of the social

criteria between the three considered attributes can

be observed in Figure 5. Globally as well as

individually, the groups give more weight to

employment, with the exception of the LSEC group.

In this case, recreational and educational activities

are the objectives with greatest priority. Even though

at a regional level there are landscape regulations

and programs, these are the objectives with less

weight, except for the group of forest research and

education, which gives greater importance to the

landscape than to educational and recreational

activities.

Even though economic criteria are not very

relevant in the Mediterranean forest, some activities

and services have more importance than the rest.

0

0,1

0,2

0,3

0,4

0,5

0,6

Social

Economic

Environmental

0

0,1

0,2

0,3

0,4

0,5

0,6

0,7

0,8

Social

Economic

Environmental

ICORES 2012 - 1st International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

104

Figure 5: Priorities of Social Objectives of Valencian

Forest by stakeholder groups.

Figure 6: Priorities of Economic Objectives of Valencian

Forest by stakeholder groups.

Rural tourism, hunting and fishing and the income

from renewable energies (biomass and wind energy)

are the greatest ones as we can see in Figure 6. This

figure also shows the not at all negligible economic

interest of the quarries (clay, gravel, sand…), that

nowadays overtakes the productivity of more

traditional activities of wood and livestock

production.

Figure 7: Priorities of Environmental Objectives of

Valencian Forest by stakeholder groups.

Figure 7 represents the weights obtained for the

environmental attributes. Hydrological regulation

and erosion control stand out above the others.

Climate change mitigation and the minimization of

biodiversity loss have similar weights individually

and globally for all of the considered groups. In this

case we do not have consistent surveys from the

LSEC group, which is the reason why this group

does not appear in Figure 7.

4.2 Global Priorities of Management

Strategies

As the contribution of management strategies to the

objectives of the third level of the decision hierarchy

(Figure 1) is not a matter of preference, but of

technique, our second survey was conducted only

among experts in forest management; from the

administration services, people who are dedicated to

research and university teaching and people in

positions of responsibility in forest enterprises.

Experts who participated in this second survey

also responded consistently to the first survey. In

this case they made judgments comparing pairs of

management strategies (the fourth level of the

hierarchy, Figure 1) establishing their relative

contribution to the corresponding objective of the

third level, on the assumption that the same amount

of money is spent on both. We assumed that the

matrix was reciprocal and only used the consistent

matrices.

First, we calculated the local priorities of the

strategies for each of the objectives, except for

mining as this is an industrial activity which is not

funded by the forestry administration. We then

obtained the overall priorities of the strategies in a

distributive mode weighting the local priorities with

the weights obtained in the first survey to the criteria

and objectives of the second and third levels of the

hierarchy. The sum of all global priorities of

strategies is, therefore, equal to 1 (Saaty, 2006).

In Figure 8 we can see the results of the overall

priorities of management strategies for each

stakeholder group. Reforestation and forestry are the

most important lines of action, followed closely by

fire prevention and extinction and pest control. In all

groups both of these lines of action account for over

50% of the global priority. The third is Forest

research, inventory and planning, their weight

varying amongst the groups, between 15 and 20%

approximately. The overall weight of the other three

strategies varies from one group to another. In the

global ranking the first strategy is the management

of hunting and fishing, followed by the flora and

fauna and finally the lowest priority is trails and

other recreational facilities with a weight below

0

0,1

0,2

0,3

0,4

0,5

0,6

0,7

Employment

RecreationalAct.

Landscape

0

0,05

0,1

0,15

0,2

0,25

0,3

0,35

0,4

0,45

WoodProduction

Huntingand Fishing

Livestock_OP

RuralTourism

RenewableEnergies

Mining

0

0,1

0,2

0,3

0,4

0,5

0,6

HydrologicalRegulation and

ErosionControl

ClimateChange Mitigation

Biodiversity

AGGREGATION OF STAKEHOLDER PREFERENCES IN SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT USING AHP

105

Figure 8: Global priorities of strategies by stakeholder

groups.

10%. Global priorities, referring only to public

forests, are similar, given the small difference

between the weights of the social, economic and

environmental criteria for public and for all forests.

In 2010 over 147 million Euros were spent in the

forest management of public and private forests.

Preventing and extinguishing fires, pest prevention

amounted to 76% of the total. Excluding funding for

forest fire fighting, if we have into account the

budget distribution between different forest

management strategies, we find a distribution closer

to the reflecting the priorities of the social groups

considered. However, we can observe the following

considerations. About 43% of the budget is

dedicated to the prevention of fires and pests,

occupying the first place, while the money for

reforestation and forestry is 24% of the total. In

priorities, the order in the ranking is reversed and

slightly more for reforestation and forestry. The

priority of forest research, inventory and planning is

18%, while receiving only 3.5% of the budget.

However, the situation in trails and other

recreational and tourism infrastructure is the reverse,

receives 17% of the overall budget and give

stakeholders a priority only 9% obtained with AHP

method. The management of hunting and fishing

also receives less funding (3%) than would result

from taking into account the priority of the

stakeholders (11%). Finally, management of flora

and fauna receives a percentage of funds (9.4%)

very similar to the value of priority obtained for all

groups together (10%).

5 CONCLUSIONS

We have used the Analytic Hierarchy Process to

develop a sustainable forest management model that

will allow us to adequately inform public policies in

a region with an important part of the territory of

which is formed of Mediterranean forest. This

ecosystem is one of the most vulnerable and its

current importance lies in the environmental services

provided, along with the social and economic ones

other than the traditional wood and livestock

services. AHP is a powerful and useful method that

easily allows the integration of the concept of SFM

and public participation through the preferences of

stakeholders and also allows the quantification of the

priorities that characterize the various stakeholders.

The empirical model that we have developed has

allowed us to quantify the increased importance of

environmental and social criteria compared with the

economic criteria in the Mediterranean forest. We

have also highlighted that stakeholder groups show

very few differences between the strategic

management of public forests and that of forest land

management in total. This is a very interesting

result, given that two thirds of the forest are

privately owned and currently give little or no

economic return to most of the owners.

Job creation is the most important social goal for

most stakeholders, with a total contribution close to

50%. However, there are differences between

groups; the other half is divided between recreation

activities and landscape. We have quantified a

greater contribution of hunting and fishing to the

economic criteria than the traditional activities of

timber production and livestock. Quarries are also of

greater importance than timber and livestock. Rural

tourism and renewable energies such as biomass and

wind energy are the most important objectives along

with hunting and fishing. The stakeholders have

shown that the role of forests in water regulation and

prevention of desertification has a higher priority

than its role in mitigating climate change and loss of

biodiversity. With regard to the priorities for the

action plans, we can say that society places a higher

priority on reforestation and forestry than the

prevention and extinction of fires, which is where

the forest administration spends the greater part of

its budget. Forest administration also spends

proportionally more on promoting recreational

activities than is suggested by the priorities obtained

using AHP. On the other hand, the stakeholders

place greater importance on furthering investigation,

carrying out forest inventories and supporting

adequate planning than is indicated by the funds

actually invested in these activities.

Finally, we wish to say that it would be very

interesting to compare the results of this research

with the analysis of the data using other multiple

criteria techniques, such as goal programming and

outranking methods. An analysis that studied the

subject using various different approaches would

help to give greater credibility to, and help promote

0,00

0,05

0,10

0,15

0,20

0,25

0,30

FirePreventionandExtinction. Pest

Prevention

ReforestationandForestry

Huntingand FishingSpeciesManagement

ManagementofFloraand Fauna

TrailsandOtherRecreationaland

Tourisminfrastr ucture

ForestResearch,Inve ntoryand Planning

ICORES 2012 - 1st International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems

106

the acceptance of, the conclusion which we have

obtained.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the support received from

the Ministry of Science and Innovation through the

research project Modelling and Optimisation

Techniques for a Sustainable Development, Ref.

EC02008-05895-C02-01/ECON, as well as the time

and expert judgments from all the stakeholders

involved in workshop and surveys we have carried

out.

REFERENCES

Ananda, J. 2007. Implementing Participatory Decision

Making in Forest Planning, Environmental

Management, 39, 534-544.

Ananda, J. and Herath, G., 2008. Multi-attribute

preference modelling and regional land use planning,

Ecological Economics, 65, 325-335.

Ananda, J. and Herath, G. 2009. A critical review of

multi-criteria decision making methods with special

reference to forest management and planning,

Ecological Economics, 68, 2535-2548.

Belton, V., and Stewart, T. J. 2003. Multiple Criteria

Decision Analysis— an integrated approach. Kluwer

Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Díaz-Balteiro, L. and Romero, C. 2008. Making forestry

decision with multiple criteria: A review and

assessment, Forest Ecology and Management, 255,

3222-3241.

Díaz-Balteiro, L.; González-Pachón, J. and Romero, C.

2009. Forest management with multiple criteria and

multiple stakeholders: An application to two public

forests in Spain, Scandinavian Journal of Forest

Research, 24, 87-93.

FORSYS. 2011. Forest Management Decision Support

Systems. http://fp0804.emu.ee/wiki/index.php/Partici

patory_processes

IPCC. 2007. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Fourth Assessment Report. Climate Change 2007:

Synthesis Report. Summary for Policymakers

Kangas, A.; Saarinen, N.; Saarikoski, H.; Leskinen, L. A.;

Hujala, T. and Tikkanen, J. 2010. Stakeholder

perspectives about proper participation for Regional

Forest Programmes in Finland, Forest Policy and

Economics, 12, 213-222.

Keeney, R. L. 2002. Common mistakes in making value

trade-offs, Operations Research, 50 (6), 935-945.

Martell, D. L.; Gunn, E. A. and Weintraub, A. 1998.

Forest management challenges for operational

researchers, European Journal of Operational

Research 104, 1 –17.

Mendoza, G. A. and Martins, H. 2006. Multi-criteria

decision analysis in natural resource management: A

critical review of methods and new modelling

paradigms. Forest Ecology and Management. 230, 1-

22.

Nordström, E. M.; Romero, C.; Eriksson, L. O. and

Öhman, K. 2009. Aggregation of preferences in

participatory forest planning with multiple criteria: an

application to the urban forest in Lycksele, Sweden.

Can.J.For.Res., 39, 1979-1992.

Nordström, E. M.; Eriksson, L. O. and Öhman, K. 2010.

Integrating multiple criteria decision analysis in

participatory forest planning: Experience from a case

study in northern Sweden. Forest Policy and

Economics, 12,562–574

PATFOR, 2011, Plan de Acción Territorial Forestal de la

Comunitat Valenciana, Generalitat Valenciana, http://

www.cma.gva.es/web/indice.aspx?nodo=72266&idio

ma=C.

Saaty, T. L. 2006. Fundamentals of decision making and

priority theory with the analytic hierarchy process

.

RWS Publications, Pittsburgh,USA.

Saaty, T. L. and Peniwati, K. 2008. Group Decision

Making: Drawing out and Reconciling Differences.

RWS Publications.

Saaty, T. L. and Shih, H. 2009. Structures in decision

making: On the subjective geometry of hierarchies and

networks, European Journal of Operational Research,

199, 867-872.

SuperDecisions.2010. http://www.superdecisions.com/

Xu, Z. 2000. On consistency of weighted geometric mean

complex judgement matrix in AHP. European Journal

of Operational Research, 126, 683-687.

AGGREGATION OF STAKEHOLDER PREFERENCES IN SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT USING AHP

107