THE JUSTIFICATION OF THE USE OF INFORMATION

TECHNOLOGY IN PATIENT SAFETY INITIATIVES

Kathleen Detar Gennuso

Department of Healthcare Ethics, Duquesne University, 600 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA, 15282, U.S.A.

Keywords: Patient safety, Human factors, Analytical methods, Ethical issues.

Abstract: Using information technology (IT) to reduce adverse events in healthcare has been a growing trend since its

endorsement in the 1999 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report. The implementation of comprehensive

information systems in healthcare practices has proved to be a path riddled with pitfalls. Not unlike other

industries, initially there are more failure stories than successes. Unfortunately the more comprehensive the

technology, or the wider the span of the implementation, the more difficult it is to achieve success. This

paper looks at the need for information technology (IT) in patient safety initiatives. Based on this

foundation, it examines critical concepts in the process of implementation of systems supporting patient

safety initiatives. Last, the paper identifies a sampling of ethical issues that commonly arise when IT is

utilized in patient safety initiatives. Even though a transformational application of IT in this type of

endeavor is difficult, it does not undermine the significant benefits that automation can provide and is

required to provide by society and the law.

1 THE NEED FOR THE USE

OF IT IN PATIENT SAFETY

INITIATIVES

Patient safety, as defined by the U.S. National

Patient Safety Foundation, is concerned with the

avoidance, prevention, and improvement of adverse

events or injuries caused by the process of

healthcare. It is understood that safety is the

outcome of the interaction of the variables in a

situation. It is not based solely on the actions of a

person; nor is it an organization’s responsibility, but

rather, it is a holistically driven outcome. An

adverse event is defined as an injury caused by

medical management, rather than the disease

process, that results in either prolonged hospital stay

or disability at discharge. A patient safety practice is

a process by which the probability of adverse events

resulting from exposure to the healthcare system,

across a range of diseases and procedures, can be

reduced or avoided.

(Vincent, 2010) These

processes, entwined in human intervention, become

candidates for automation.

Methods will produce different levels of

effectiveness; for example, Leape’s study suggests

that voluntary self-reporting will catch one in 500

adverse events, while the combination of

computerization and chart review will catch one in

ten adverse events. (Leape, 2002) Unfortunately the

risk is not proportional; some patients may be at

higher risk to suffer an adverse event or prone to the

possibility of multiple events. In fact, studies report

that a patient in ICU stands to suffer from 1.7 errors

made in their care per day. (Spear, 2005)

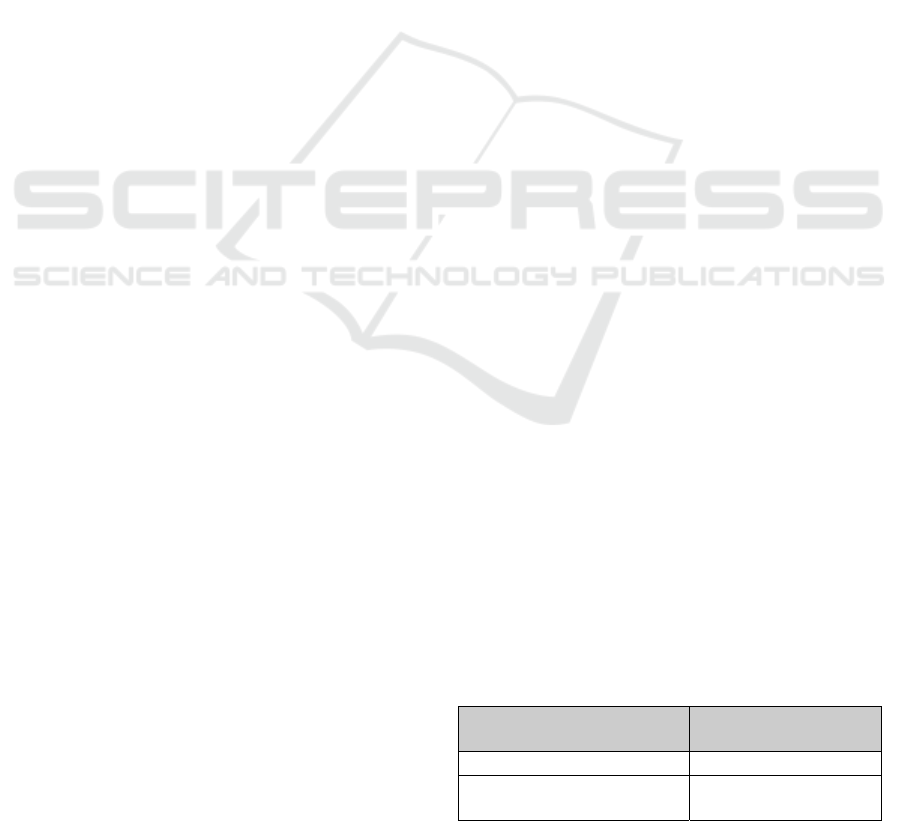

Table 1: Comparative Effectiveness of Patient Safety

Initiatives.

Patient Safety Initiative

Adverse Events

Identified

Voluntary Self-Reporting 1/500

Computerization and Chart

Review

1/10

1.1 Human Limitations and

Organizational Memory

Since the invention of the computer in the 1950s, the

key driver of its use has been the desire to retain and

use data that the human brain does not have the

capacity to maintain. Yet, significant resistance

143

Detar Gennuso K..

THE JUSTIFICATION OF THE USE OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IN PATIENT SAFETY INITIATIVES.

DOI: 10.5220/0003726501430146

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2012), pages 143-146

ISBN: 978-989-8425-88-1

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

exists when it comes to turning over decision

making to a computer. The fact is, machines are

better at doing some things than humans are, while

other tasks are better left alone; it is the ability to

know the difference that is in short supply. The

challenge lies in identifying the need for and

persuading others to make use of computer systems,

or, to rely solely on human intervention, or take

advantage of both.

Information is the key asset of the knowledge

organization. As individuals have limitations with

their memory so do organizations that do not use

automation to manage better processes. Efficient

automation extends and amplifies an organization’s

memory by capturing, organizing, disseminating,

and reusing the knowledge created by its employees.

However, organizational memory is not just a

facility for accumulating and preserving

information; in fact, greater value is achieved via

sharing knowledge.

1.2 Proven Success in Reduction of

Errors through Automation

As knowledge is made explicit and managed, it

augments the organizational culture, thereby

providing a basis for communication and learning.

In 2006, a comprehensive analysis of the literature

that existed on the effects of healthcare IT systems

on the quality and efficiency of care was completed.

The research uncovered evidence that implementing

a multifunctional automated healthcare system could

increase the delivery of care that adhered to

guidelines and protocols; enhance the capacity of the

providers of healthcare to perform surveillance and

monitoring for disease conditions and care delivery;

reduce rates of medication errors; and decrease

utilization of care. Effects on the efficiency of care

and the productivity of physicians were mixed.

(Blumenthal, 2007)

In 2003, Bates asserted that these systems reduce

medication error by 55 percent. Approximately 28

percent of adverse events is attributed to medication

errors and viewed as preventable. Fifty six percent

of these errors occurred when drug orders were

being placed, which automated systems would most

likely have prevented. In addition, bar coding used

in medication systems has proven to reduce drug

errors by more than 50 percent, preventing

approximately 20 adverse drug events per day.

Although the ultimate goal is to protect patients,

these measures improve the bottom line, since the

average adverse event costs an estimated $4,700 per

patient in extra hospital days and ancillary services

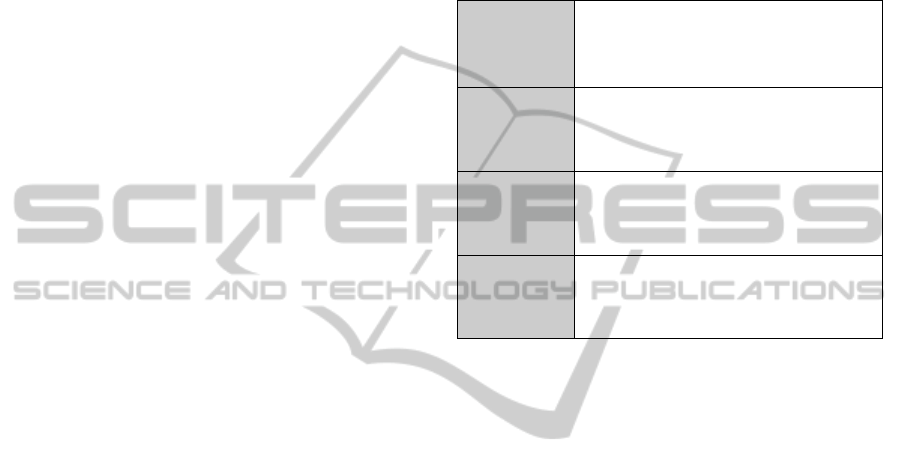

Table 2: Impact of automated systems on drug error rates.

Percentage of total

adverse effects that

are drug-related

Percentage of total adverse

effects that are drug-related

when bar coding technology

is utilized

28% 14%

excluding the cost of litigation. (Bates, 2003)

As

healthcare gets more complex, with patients having

multiple prescriptions and physicians, tracking

medical records (EHR) is adding to the problem of

patient safety.

1.3 The Velvet Hammer:

Electronic Healthcare Records

EHR automates the manual or semi-manual keeping

of records. A survey conducted by the Medical

Records Institute, shows that providers rank the

ability to share information as the top benefit of

EHR, followed by better quality of care, improved

workflow and documentation, and reduction of

medical errors.

In 2009, U.S. Congress provided

incentive and motivation to use IT to increase the

usage of EHR, benefiting patient safety initiatives as

well. The Health Information Technology for

Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH)

authorized incentive payments through Medicare

and Medicaid to clinicians and hospitals when they

use EHRs privately and securely to achieve specified

improvements in care delivery.

Using IT to reduce

adverse events across the entire continuum of care

incorporates the requirement of meaningful use.

2 IMPLEMENTING PATIENT

SAFETY INITIATIVES

WITH IT

There are a number of methods of investigation and

analysis available in healthcare. A more recent

paradigm includes the possibility for human error

and is based on the premise that safety depends on

creating systems that plan for errors or anticipate

errors in order to prevent them before they happen.

British psychologist, James Reason, developed a

Swiss cheese model to represent organizational

accidents, which became widely accepted. This

model’s critical point is that in complex structures, a

single, sharp-end error rarely is enough to cause

harm. Instead, this type of error must penetrate

several layers of incomplete protection to cause a

devastating result. Reason’s model moves the focus

HEALTHINF 2012 - International Conference on Health Informatics

144

from trying to perfect human behavior to fixing the

holes in the Swiss cheese, often called latent errors.

In addition, the layers of overlapping protection

must be put in place to decrease the probability of

the sharp end or root cause making the error possible

or inevitable. (Reason, 1995)

A number of analysts have identified a schema of

most common medical error root causes. The most

widely accepted is Charles Vincent’s adapted

directly from Reason’s model. His schema forces the

reviewer to ask basic questions as to whether there

should have been a checklist or read-back, whether

the resident was too fatigued, or whether the nurse

was too intimidated to speak up. Usually, a wide

variety of contributory factors lead up to the event;

therefore, Vincent extended the root cause of the

incident from a single root cause, to multiple.

Vincent’s model also moves the target past the cause

of the incident. Though important, it is not the final

goal of uncovering the gaps and inadequacies in the

healthcare system. It concentrates on accident

causation, reducing the focus on the individual

persons who may have made an error and aiming it

instead on pre-existing organizational factors.

The

framework essentially summarizes the major

influences on clinicians in their daily work and the

systemic contributions to adverse outcomes versus

good outcomes. (Vincent, 2010)

In the U.S., a

national database (by AHRQ) has developed a

starting point for healthcare organizations by

identifying 27 patient safety indicators, which

measure outcomes that are possible in patient safety

events. Using a proven approach is a key tenet in IT

systems and provides a launch point for patient

safety initiatives and automation.

2.1 Realistic Expectations

There have been several cautionary studies on the

effects on patients' health when using healthcare IT

systems, from harm to mortality. In addition, though

temporary, during transition and implementation

physicians can see up to a 10 to 20 percent reduction

in productivity for a period of six months or more.

The most significant drawback to the use of IT or its

success again comes back to the nature of human

involvement. Though hardware malfunctions can

happen, studies show that zero tolerance machines

exist and stay up consistently. The true problem is

the same as it has been since the invention of the

computer; it is how human beings designed the

system, many times ignoring the real-life way

clinicians go about doing their jobs and ignoring the

way they interact. Second, the implementation

mechanism for these types of systems is commonly

flawed due to numerous resource issues (such as

people, time and money). Technology adaptation is

not a concept of the future, but rather is engrained in

the current individuals entering the healthcare field.

The problems are known; the answers will be found

in overcoming the obstacles.

Table 3: Project implementation considerations.

Application

Ease of navigation

Functionality must be perceived as

better

Cutover strategy

People

Executive champion

Stakeholder buy-in

Clear roles, responsibilities,

expectation

Process

Disciplined procedures

Automated control system

Structured reviews and sign-offs

Communication strategy

Training

Multiple levels of training by role

Provided at the right time, quantity,

and quality

Hands-on commissioning

3 ETHICAL ISSUES IN PATIENT

SAFETY INITIATIVES USING

INFORMATION

TECHNOLOGY

In the U.S., HIPAA regulations released in 2003

served as the means for regulating IT utilization in

healthcare initiatives. Compliance with HIPAA was

required by April 14, 2003, and the regulations, still

in place today, applied to both electronic and paper

records.

3.1 Autonomy of Patient

Under the regulations, patients have the right to

inspect and obtain a copy of their entire medical

record, with the exception of notes from

psychotherapy. A physician can refuse to make the

entire record available in cases in which harm to the

life or physical safety of the individual or another

person may occur. A person also has the right to an

accounting of disclosures of protected health

information made over the previous six years. There

are, however, numerous exceptions to this

accounting requirement.

One study showed that patients having access to

their healthcare records electronically expressed

THE JUSTIFICATION OF THE USE OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY IN PATIENT SAFETY INITIATIVES

145

high value and interest in the concept of autonomy

and welcomed greater access and control of their

health information. While highly valued, autonomy

was perceived as a double-edged sword. Sticking

points, including concerns about the locus of

responsibility for maintaining the accuracy and

integrity of the information, were raised. Substantial

variability based on age (over 35) was evident in

opinions about the safety of their records. (Halamka,

2008)

3.2 Privacy of Data

Patients have had a right to have personal medical

information kept private since the days of

Hippocrates. Physicians have an obligation to keep

medical information secret. The chief public policy

rationale is that patients are unlikely to disclose

intimate details that are necessary for their proper

medical care to their physicians unless they trust

their physicians to keep that information secret.

Basic privacy doctrine in the context of medical care

holds that no one should have access to private

healthcare information without the patient's

authorization and that the patient should have access

to records containing his or her own information, be

able to obtain a copy of the records, and have the

opportunity to correct mistakes in them.

Without informed consent, outside the context of

treatment, a patient's entire medical record can

seldom be lawfully disclosed. The HIPAA

regulations set a federal minimum, or floor, not a

ceiling, on the protection of privacy. Thus, when

other federal laws (such as laws protecting drug and

alcohol treatment records) or state laws (such as

laws that provide special protections for mental

health or genetic records) provide more protection

for patients' privacy than the new regulations, the

more protective federal and state laws will continue

to govern.

3.3 Moral Agency

The privacy of the information that is maintained in

electronic storage and the freedom it provides is

dependent on the personal integrity of employees

and others who will likely never see patients or meet

those who could be adversely affected by the

systems being developed. IT professionals have no

standard code of ethics. Not surprisingly, day-to-day

decision making comes down to moral agency and

personal ethics. However, human beings by nature

have the capacity to recognize normative standards

expected of their role or position. It is well accepted

that this capacity brings with it accountability for

one’s actions, even without a code of ethics.

Personal integrity will provide this type of

accountability; however, without checks and

balances, personal policing may not be enough to

compensate for human errors.

4 CONCLUSIONS

The very low levels of adoption of the key health

information technology systems required for

meaningful use may indicate that hospitals face

difficulty in achieving the level of use required to

receive government incentive payments.

This

finding suggests a very specific need among

hospitals for a greater look at the areas addressed in

this paper, specifically, understanding the need for

automation, the implementation issues, and ethical

challenges in utilizing IT in patient safety initiatives.

REFERENCES

Bates, D.W, Gawande, A, 2003. Improving Safety with

Information Technology, New England Journal of

Medicine 348, no. 25.

Blumenthal, David, Glaser, John, 2007. Information

Technology Comes to Medicine, New England Journal

of Medicine 356.

Halamka, John D., Mandl, Kenneth D, Tang, Paul C.,

2008. Early Experiences with Personal Health

Records, Journal American Medical Information

Association; 15(1).

Leape, L.L., 2002. Reporting of Adverse Events. New

England Journal of Medicine, 347.

Reason, J.T., 1995. Human Error. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Spear, Steven J, Schmidhofer, Mark, A., 2005. Ambiguity

and Workarounds as Contributors to Medical Errors,

Journal Annals of Internal Medicine, V 142:8.

Vincent, Charles, 2010. Patient Safety, Wiley-Blackwell,

2

nd

Edition.

HEALTHINF 2012 - International Conference on Health Informatics

146