TOWARD A SILENT SPEECH INTERFACE BASED ON UNSPOKEN

SPEECH

Alejandro Antonio Torres García, Carlos Alberto Reyes García and Luis Villaseñor Pineda

Computer Sciences Department, National Institute for Astrophysics Optics and Electronics

Luis Enrique Erro # 1, Tonantzintla, México

Keywords:

Silent Speech Interfaces (SSI), Electroencephalograms (EEG), Unspoken Speech, Discrete Wavelet Transform

(DWT), Classification.

Abstract:

This work aims to interpret the EEG signals associated with actions to imagine the pronunciation of words

that belong to a reduced vocabulary without moving the articulatory muscles and without uttering any audi-

ble sound (unspoken speech). Specifically, the vocabulary reflects movements to control the cursor on the

computer. We have recorded EEG signals from 21 subjects using a markers based basic protocol. The dis-

crete wavelet transform (DWT) is used to extract features from the delimited windows, and a subset of them

with frequency ranges below 32 Hz is further selected. These subsets are used to train four classifiers: Naive

Bayes (NB), Random Forests (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and Bagging-RF. The results are still pre-

liminary but encouraging because the accuracy rates are above 20%, i.e. up to chance for five classes. The

implementation process as well as some experiments with their corresponding results are shown.

1 INTRODUCTION

Oral communication is the natural way in which hu-

mans interact. However, in some circumstances, it is

not possible to emit an intelligible acoustic signal, or

it is desired to communicate without making sounds.

In these conditions systems that enable spoken com-

munication in the absence of an acoustic signal are

desirable. This kind of systems are part of a recent

research area called silent speech interfaces (SSI).

Among the SSI technologies described by Denby

(Denby et al., 2010), of particular interest are those

that use EEG because they are non invasive, rela-

tively simple, economical, and insensitive to environ-

ments with large amounts of audible noise. Particu-

larly those associated with unspoken speech, also re-

ferred as internal or imagined speech.

Works using unspoken speech can be divided into

two approaches: by words and by syllables. The first

approach is followed in (Porbadnigk, 2008; Suppes

et al., 1997; Wester, 2006). While in (Brigham and

Kumar, 2010; DaSalla et al., 2009; D’Zmura et al.,

2009) only syllables are treated. In the specific case of

works that explore words, where this study falls, the

following problems had been identified. In (Suppes

et al., 1997) was presented a prototypes based method

that is not unsuitable for real-time processing. While

in (Porbadnigk, 2008; Wester, 2006) it is assumed that

the extracted features can be recognized with existing

models for common speech recognition, nonetheless

speech acoustic signal and EEG signals have very dif-

ferent characteristics. In the words approach, the most

recent work described in (Porbadnigk, 2008) uses a 5

words vocabulary, EEG signals from seven subjects

were recorded, and each word of vocabulary was re-

peated 20 times.

This research aims to interpret the EEG signals as-

sociated with unspoken speech. Specifically, it aims

to interpret the signals to recognize five unspoken

words of the Spanish language: “arriba”, “abajo”,

“izquierda”, “derecha”, and “seleccionar”, which are

repeated 33 times by each subject. They were chosen

because with them it could be possible to control a

computer screen cursor.

2 METHODOLOGY

The stages of proposed methodology are the follow-

ing: EEG signal adquisition, EEG signal enhance-

ment (Pre-processing), feature extraction, feature se-

lection, and classification.

For EEG signal acquisition an EMOTIV kit is

370

Antonio Torres García A., Alberto Reyes García C. and Villaseñor Pineda L..

TOWARD A SILENT SPEECH INTERFACE BASED ON UNSPOKEN SPEECH.

DOI: 10.5220/0003769603700373

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing (BIOSIGNALS-2012), pages 370-373

ISBN: 978-989-8425-89-8

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

used. This kit is wireless and has fourteen high resolu-

tion electrodes (channels) whose sampling frequency

is 128 Hz.

2.1 Brain Signals Acquisition

In this stage the EEG kit is used to acquire the

brain signals. According to the Geschwind-Wernicke

model, EEG signals related to speech production

come from specific areas in the left side of the brain

(Geschwind, 1972). Particularly, channels F7, FC5,

T7 and P7 are of interest because they are the nearest

to Geschwind-Wernicke’s model areas.

Moreover, a basic protocol is used to acquire EEG

signals from each subject, a mouse is used to send

markers to the EEG signals acquisition software, to

delimit the start and end of imagining the pronunci-

ation of the words (see Figure 1). A set of samples

between both markers is called window or instance.

Considering that, it is known in what part of the

EEG signal the patterns associated with the imagina-

tion of the word pronunciation should be searched.

Figure 1: EEG signal from F7 channel that it belong subject

S1 while he imagines word pronunciation“abajo” following

the data acquisition protocol.

2.2 Pre-processing

In this stage, the EEG signals obtained from the chan-

nels of interest (F7, FC5, T7 y P7) are filtered using

a finite impulse response (FIR) band-pass filter at the

range 4 to 25 Hz.

It is noteworthy that, similarly to conventional

speech, the duration of the unspoken speech’s win-

dows for each word is variable, for one subject as well

as for different subjects. Thus, it is necessary to es-

tablish an equal size for all windows.

At the end of this stage windows with 256 sam-

ples and a frequency range between 4 and 25 Hz. are

kept and used for the creation of the experimental data

base. Windows lower than 256 samples are completed

with zeroes, and those with more than 256 samples

are discarded.

2.3 Feature Extraction

In (Lotte et al., 2007) it is mentioned that the features

to be used in BCI are not stationary and con-

tain time information, which makes necessary an ad-

equate representation. The discrete wavelet transform

(DWT) provides a highly efficient wavelet represen-

tation by restricting the variation in translation and

scale, usually to powers of two.

In consequence, in this work the discrete wavelet

transform (DWT) with six decomposition levels is

applied, using a second order Daubechies (db2) as

mother wavelet function. With this, a vector with 269

wavelet coefficients is obtained for each window in

each of the interest channels. Subsequently, the co-

efficients in the same time interval that belong to the

four interest channels are concatenated following this

order F7-FC5-T7-P7. At the end of this stage is ob-

tained a vector with 1076 features, and its correspond-

ing class label is obtained.

2.4 Feature Selection

The feature selection problem implies to select a min-

imum subset, with M features, S = (S

1

, ..., S

M

) from

original feature set F = (F

1

, · · · , F

N

), where M ≤ N

and S ⊆ F, so that the feature space is optimally

reduced and the classification performance is main-

tained, improved or not significantly degraded.

At this stage, the subset of features greater than

25 Hz. is discarded. Therefore, the feature subset se-

lected consists of the detail coefficients D2 to D6 and

the approximation A6 which reduces the dimension of

the feature vectors, and at the same time reduces the

impact of the curse of dimensionality in the classifi-

cation stage. With this, each window of each channel

is represented with 140 wavelet coefficients. Then,

the DWT coefficients of windows in the same time

interval were concatenated as in the feature extraction

stage.

2.5 Classification

In this work the following three classifiers are trained

and tested: Support Vector Machines (SVM), Ran-

dom Forests (RF) and Naive Bayes (NB). After eval-

uating the individual classifiers, the classifier with the

higher accuracy percentage is selected to use it as the

base classifier in Bagging ensamble.

TOWARD A SILENT SPEECH INTERFACE BASED ON UNSPOKEN SPEECH

371

3 EXPERIMENTATION AND

RESULTS

3.1 Preliminary Experiments

Preliminary experiments consisted in training and

testing the three described classifiers (NB, RF, and

SVM) with the EEG signals recorded from three sub-

jects (S1, S2 and S3). Previously, complete and re-

duced feature vectors are obtained. These experi-

ments aim to evaluate the convenience of using the

complete or reduced vectors, and select the classifier

to be used as a basis for the Bagging classification.

For this purpose, the measure to evaluate the classi-

fiers is accuracy. The classification accuracy is ob-

tained through 10-fold cross validation.

The accuracy percentage for each of the three clas-

sifiers using the complete feature vectors are in table

1.

Table 1: Accuracy percentages obtained for the classifiers

using the complete feature vectors (1076 features).

Accuracy

Subject NB RF SVM

S1 23.35 24.08 23.35

S2 17.09 31.63 24.78

S3 35.75 41.21 18.18

Table 2 presents the accuracy percentage for each

of the three classifiers using the reduced feature vec-

tors.

Table 2: Accuracy percentages obtained for the classifiers

using the reduced features vectors (540 features).

Accuracy

Subject NB RF SVM

S1 24.08 43.78 21.9

S2 18.8 38.46 21.37

S3 33.94 43.64 19.39

The results described in tables 1 and 2 show that,

generally, better results are obtained when using the

reduced feature vectors than when using complete

vectors. Nonetheless, in occasions when better results

are obtained using the whole vectors, the improve-

ment is not significant.

In addition, the tables 1 and 2 show that the clas-

sifier which obtains the best accuracy percentages is

RF, so it was selected to be used for the following

experiments as the base classifier for Bagging. From

here, this ensemble will be denoted as Bagging-RF.

3.2 Experiment with the Whole Corpus

In these experiments participated 21 right-handed

subjects (S1-S21) to collect a corpus of data. From

each of them 33 instances of each of the five imag-

ined words were recorded. However, those instances

with more than 256 samples (two seconds long), are

discarded in the experimental phase. After that se-

lection process, the remaining instances pass by all

methodology stages.

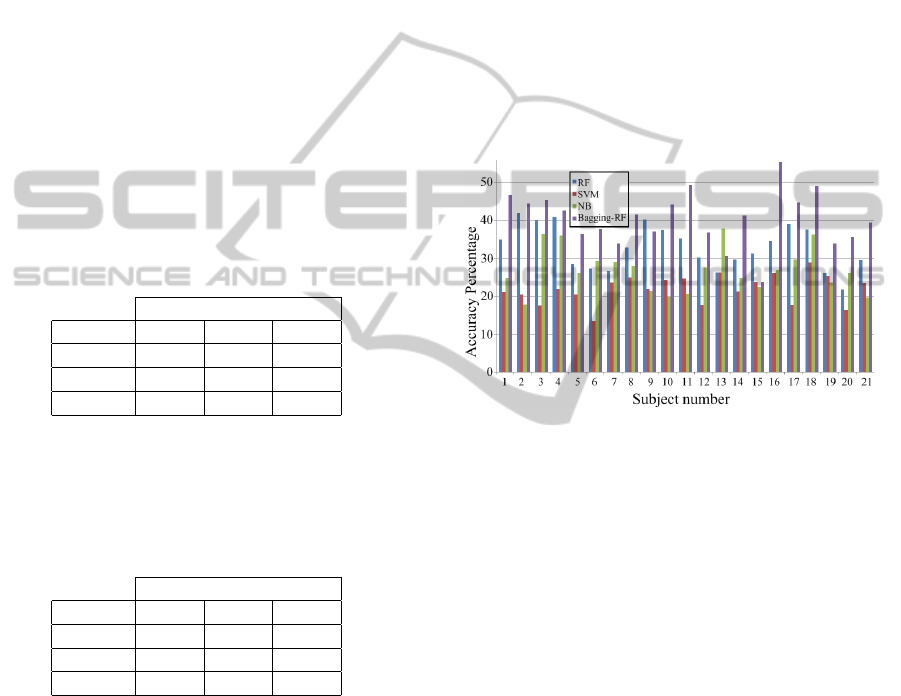

In the first experiment the instances from each of

the twenty-one subjects (S1-S21) are separately uti-

lized for training and testing the four evaluated classi-

fiers (RF, SVM, NB, Bagging-RF). The accuracy per-

centages are obtained using 10-folds cross validation.

In figure 2 these percentages are shown.

Figure 2: Accuracy percentages for each classifier obtained

after 10-folds cross validation on the data of each subject.

Figure 2 shows that, generally, the accuracy per-

centages obtained by the four classifiers are above

chance for five classes, which is 20%. This accuracy

rate is taken as a lower bound because, according to

(Dietterich, 2000), “an accurate classifier is one that

has an error rate better than chance at the stage of

generalization (testing)”. Furthermore, figure 2 shows

that, according to accuracy percentages, the best clas-

sifier is Bagging-RF and the worst is SVM. Also, it

is important to note that, for all subjects both RF

and Bagging-RF are kept above chance for the five

classes.

Further on, results at word level obtained by RF

and Bagging-RF, utilizing the F-measure, are next

presented. For each subject’s dataset, the classifiers

calculate a F-measure value for each of the words.

Figure 3 shows the average F-measure obtained by

RF and Bagging-RF for each of the words. In the case

of RF, the words order according to the f-measure

from high to low, is: “arriba”, “izquierda”, “selec-

cionar”, “abajo”, and “derecha”. While, in the case

of Bagging-RF according to the same F-measure the

order is: “seleccionar”, “arriba” , “derecha”, “abajo”,

and “izquierda”.

BIOSIGNALS 2012 - International Conference on Bio-inspired Systems and Signal Processing

372

Figure 3: Graph of average f-measure for each word ob-

tained for RF and Bagging RF using 10-folds cross valida-

tion on the subject’s data.

It is important to note that, the words “selec-

cionar” and “arriba” classified by Bagging-RF have a

F-measure above 0.4, which is twice bigger than ran-

dom.

Last, it is worth to mention that in the presented

work the results obtained are relatively comparable to

state of the art similar works, like those reported in

(Porbadnigk, 2008) where the classification was eval-

uated only based in accuracy, reporting 45.95% for

five words. This comparison is mentioned consider-

ing the differences described in section 1.

4 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

The acoustic speech signal and the EEG signals have

different features, which makes them naturally dis-

similar. In consequence, we explored an alternative

processing and classification approach to treat the

EEG signals, in particular those related to unspoken

speech. Indeed, the problem of interpreting unspo-

ken speech is still far to be solved. However, from

our experiments we obtained evidence to affirm that

the EEG signals actually carry useful information to

allow the classification of unspoken words. We con-

clude this based on the percentages of accuracy in

the classification for the four classifiers, which, are

above chance for five classes (see figure 2). Our re-

sults and experimental procedures are consistent with

those reported in the state of the art, because: we per-

formed experiments with more than one classifier, we

explored a language different to English, we used a

reduced vocabulary with more semantic meaning, and

we worked with features obtained by a feature selec-

tion approach instead a dimensionality reduction ap-

proach. The average f-measure was below the per-

centages due to chance for five classes.

To improve the reported results we propose to ex-

plore how to utilize and compare all windows regard-

less their size. We propose to apply independent com-

ponent analysis (ICA) and assess each independent

component using the Hurst’s coefficient to eliminate

some artifacts as blinks and heartbeats. To select an-

other wavelet family also could help. We also plan to

test another EEG signal representation and combine

them with the DWT coefficients. Finally, it is still

possible to use hybrid intelligent systems, and others

ensemble schemes to improve classification results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was done under partial support of CONA-

CyT (scholarship # 234705), and INAOE.

REFERENCES

Brigham, K. and Kumar, B. (2010). Imagined Speech

Classification with EEG Signals for Silent Commu-

nication: A Preliminary Investigation into Synthetic

Telepathy. In Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engi-

neering (iCBBE), 2010 4th International Conference

on, pages 1–4. IEEE.

DaSalla, C. S., Kambara, H., Koike, Y., and Sato, M.

(2009). Spatial filtering and single-trial classification

of EEG during vowel speech imagery. In i-CREATe

’09: Proceedings of the 3rd International Convention

on Rehabilitation Engineering & Assistive Technol-

ogy, pages 1–4, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Denby, B., Schultz, T., Honda, K., Hueber, T., Gilbert, J.,

and Brumberg, J. (2010). Silent speech interfaces.

Speech Communication, 52(4):270–287.

Dietterich, T. (2000). Ensemble methods in machine learn-

ing. Multiple classifier systems, pages 1–15.

D’Zmura, M., Deng, S., Lappas, T., Thorpe, S., and Srini-

vasan, R. (2009). Toward EEG sensing of imagined

speech. Human-Computer Interaction. New Trends,

pages 40–48.

Geschwind, N. (1972). Language and the brain. Scientific

American.

Lotte, F., Congedo, M., Lécuyer, A., Lamarche, F., and Ar-

nald, B. (2007). A review of classication algorithms

for EEG-based brain-computer interfaces. Journal of

Neural Engineering, 4:r1–r13.

Porbadnigk, A. (2008). EEG-based Speech Recognition:

Impact of Experimental Design on Performance. Mas-

ter’s thesis, Institut für Theoretische Informatik Uni-

versität Karlsruhe (TH), Karlsruhe, Germany.

Suppes, P., Lu, Z., and Han, B. (1997). Brain wave

recognition of words. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,

94(26):14965.

Wester, M. (2006). Unspoken Speech - Speech Recognition

Based On Electroencephalography. Master’s thesis,

Institut für Theoretische Informatik Universität Karl-

sruhe (TH), Karlsruhe, Germany.

TOWARD A SILENT SPEECH INTERFACE BASED ON UNSPOKEN SPEECH

373