The Role of Smartphones as an Assistive Aid in

Mental Health

John J. Guiry

1

, Lisanne Warmerdam

2

, Patrick van der Hilst

2

, Heleen Riper

2

Pepijn van de Ven

1

and John Nelson

1

1

University of Limerick, Limerick, Ireland

2

VU University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Abstract. Recent developments in wearable sensors and smartphone technolo-

gy have demonstrated the applicability and viability of such devices to the suc-

cessful and cost effective treatment of mental illness, particularly depression.

This paper describes a software toolkit and physical activity algorithms deve-

loped at the University of Limerick that will be used to monitor and assist clini-

cal professionals in analyzing physical activity and physiological data. The re-

sulting information is used in the ICT4Depression project to deduce an indivi-

dual’s mental state, and progression through mental illness. Two trials were per-

formed to assess the algorithms and the resulting data are discussed.

1 Introduction

Major depression is currently the fourth disorder worldwide in terms of disease bur-

den, and is expected to be the disorder with the highest disease burden in high-income

countries by 2030. Current treatment methods can reduce the burden of this disease

by approximately one third [1]. ICT4Depression is an FP7 funded project that aims to

reduce the disease burden significantly further. To this end the ICT4Depression con-

sortium has set out to develop a system for the provision of online and mobile treat-

ment of depression. Where current methods rely on direct contact with health care

professionals or are Internet-based self-help therapies with a low level of interaction

with the patient, the ICT4Depression system is a responsive system that allows the

patient to receive a highly personalized and interactive treatment and work on their

own progress anywhere and anytime.

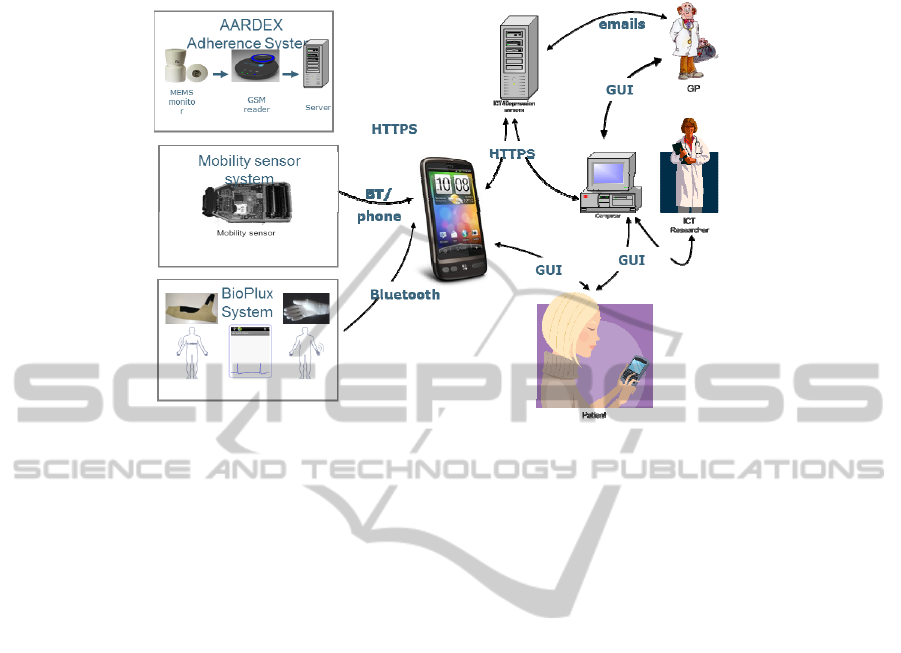

Fig.

1 presents an overview of the ICT4Depression system. Central to the technol-

ogy used is a smart phone, which is used to provide treatment to the user. This treat-

ment consists of the provision of self-help modules, the gathering of sensor data (phy-

siological sensors, activity sensors and various user ratings and questionnaires) and

the measurement of medication adherence. This information is used in a decision

support system to reason about the user’s progression and to advise on further treat-

ment if and when necessary. In addition to being able to interact with the system on

the mobile phone, the user has access to a web interface which can be used to provide

more extensive feedback to the system and to view information generated by the sys-

tem on a larger screen.

J. Guiry J., Warmerdam L., van der Hilst P., Riper H., van de Ven P. and Nelson J..

The Role of Smartphones as an Assistive Aid in Mental Health.

DOI: 10.5220/0003885601050113

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Computing Paradigms for Mental Health (MindCare-2012), pages 105-113

ISBN: 978-989-8425-92-8

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Fig. 1. Overview of the ICT4Depression System.

Sensor information plays an important role in the system as it is used in an innova-

tive way to assess the user’s treatment progression. To this end, heart rate (and varia-

bility), breathing rate and trunk acceleration are measured with a chest strap. A glove

type sensor is used to measure skin conductance and blood volume pulse with the data

analysed for emotive triggers. Using acceleration sensors on the mobile phone the

user’s physical activity is recorded. The latter plays an important role as exercise and

depression are intricately linked. Various scientific studies have shown the important

role physical activity plays in depression and it is widely known that depression tends

to result in lower patterns of physical activity. From this perspective, it is interesting

to measure the levels of physical activity for patient’s diagnosed with depression to

obtain an insight in the disease progression. However, it has also been shown that the

reverse is true and that a regime of increased physical activity can be used to reduce

the severity of the depression [2]. Several reasons for the positive effect of physical

activity on mood and depression have been suggested. First, exercise may act as a

diversion from negative thoughts. Second, the mastery of a new skill may be impor-

tant. Third, social contacts during the activity may act as a working mechanism. And

fourth, physical activity may have physiological effects such as changes in endorphin

and monoamine levels, or reduction in the levels of the stress hormone cortisol which

all may improve mood. Exercise has been found to be effective in the treatment of

depression in more than 20 randomized controlled trials [3]. Moreover, Blumenthal

reported in 1999 that 16 weeks of group exercise training was as effective as antide-

pressant treatment with sertraline and that the 10-month relapse rate for the group that

performed exercise was 8% whereas this same rate was at 38% for the group treated

with Sertraline [4].

In the ICT4Depression system exercise is recognized as a treatment in itself which

is normally conducted in parallel to other treatments. This paper discusses how smart

phone based sensors are used in the ICT4Depression project for the identification and

106

monitoring of user physical activities (measured as periods spent lying, sitting, stand-

ing, walking, running, cycling and energy expenditure).

2 Physical Activity Monitoring

Physical activity monitoring using accelerometers is a well-established art which has

seen a large interest from the research community in the last 20 years. Whereas re-

search has long focused on the use of dedicated sensors rigidly attached to the user’s

body, recent efforts have focused on use of the accelerometers available on most

modern mobile phones. Due to the high uncertainty as to the exact location and orien-

tation of the device in a realistic setting, physical activity monitoring on mobile

phones poses significant challenges. Accelerometers measure acceleration from two

sources: the output signal contains both acceleration resulting from user movement

and acceleration due to gravitational forces. If the orientation of the device is not

known a priori, as is the case for a mobile phone, it is difficult to separate the two

contributions to the acceleration output signal. For this reason early endeavours with

mobile phones focused on step count and energy expenditure measurements [5] as

both measures have the advantage that the orientation of the measurement device

need not be known. Recent developments in this area of research go a step further and

show promising results for sensors which can be attached to the user’s body with

more freedom whilst still being able to identify various physical activities [6,7]. The

methods used, typically do not explicitly separate gravitational and movement com-

ponents from the acceleration data. As a result, the wealth of existing algorithms can-

not be re-used. The work on mobility monitors described in this paper builds on the

results found in the literature, but explicitly attempts to obtain the direction of gravity

in device-fixed coordinates, such that a rotation of the measured accelerations (in

device-fixed coordinates) can be performed to world-fixed coordinates (with the grav-

ity vector pointing straight down). Where this can be done with sufficient accuracy,

existing algorithms can be employed to then obtain accurate insight in specific user

activities.

2.1 The PA Monitor

The PA monitor was developed and tested on a Samsung Galaxy S GT-I9000 which

integrates Bosch’s SMB 380 TA accelerometer. This digital accelerometer falls into

the differential capacitive line, whereby a change in capacitance can be mapped to

changes in acceleration, and consumes 290µA while in use. The Samsung uses a

1500mAh battery, with which a mobility monitoring application will run for approx-

imately 6 hours. Output RMS noise from the accelerometer is in the order of 0.5mg/

√

Hz

. Android does not allow developers to specify the sampling rate explicitly. In-

stead, suggestions are made to the Android platform, such as DELAY_NORMAL,

DELAY_UI or DELAY_FASTEST. These determine the priority with which the

accelerometer readings are processed but do not guarantee a fixed sampling rate.

Using the DELAY_FASTEST attribute on the Samsung provides applications with

samples at approximately 90Hz.

107

2.2 Data Processing

As the sampling frequency of the accelerometer is not constant, raw acceleration data

from the phone are first interpolated. A lightweight linear interpolator is used to faci-

litate any real time requirements. Interpolation facilitates processing further down the

chain, since the quantity of samples in the incoming stream becomes fixed, at 120Hz

in this case. For the case of linear interpolation, let: x = {x

m+1

, x

m+2

,…x

n-1

} be the

vector of missing data points bounded either side by the known points (x

m

, y

m

) and

(x

n

, y

n

) where n>m. The n-m-1 missing data points can be found using linear interpo-

lation between the two known points:

∀i∈

〈

m,n

〉

y

=

y

+

y

−

y

x

−x

(

x

−x

)

(1)

Next, the interpolated stream is median filtered with a 3-point median filter to elimi-

nate any sporadic spikes in the signal. This median filtered stream is then used to

fragment the acceleration signal in two using both band pass and low pass filters to

give estimated vectors for the dynamic and static (gravitational) components respec-

tively. The static and dynamic acceleration components are then fed into a physical

activity state machine algorithm to derive user physical activity.

2.3 Activity Inference

Firstly, the incoming sample stream is converted to a world fixed coordinate system

to overcome variations in the input signal due to changes in the phone’s orientation.

The transformed stream is given by: a

wf

= a

df

R, where R is the rotation matrix which

is derived from the static component of the acceleration signal, and is defined by:

1+

(

1−cos

(

))

∗(

−1) −∗

(

)

+(1−cos

(

)

)

∗∗ ∗sin

(

)

+(1−cos

(

)

)

∗∗

∗sin

(

)

+

(

1+cos

(

))

∗∗ 1+

(

1−cos

(

))

∗(∗−1) −∗sin

(

)

+

(

1−cos

(

))

∗∗

− ∗ sin

(

)

+

(

1−cos

(

))

∗∗ ∗sin

(

)

+

(

1−cos

(

))

∗∗ 1+

(

1−cos

(

))

∗(∗−1)

Once world-fixed accelerations are available, traditional physical activity algorithms

can be used. The first step undertaken to achieve activity recognition involves select-

ing a heuristic feature set. The features chosen to distinguish between high and low

energy activities are one-dimensional counts per minute (CPM) and the coefficient of

variation (CV) [8], which give an indication of the energy contained in the accelera-

tion signal and the variation in the latter respectively. Formulae for these can be found

in equation 2 and 3.

CPM(

k

)=

|

(+ )

|

N

(2)

C

V

(

k

)

=

Standard De

v

(

|

(: + −1)

|

)

|

mean(

(: + −1))

|

(3)

where a

z

is the component of the acceleration pointing straight down and N is the

number of samples collected in a 1 minute window starting at time k.

Whereas the CPM is per definition high for high energy activities, the CV is rela-

tively low in these cases. CV tends to be high for sedentary activities as small move-

108

ments results in the CV increasing significantly. Hence these features are ideal candi-

dates for the classification of high energy versus sedentary activities. Moreover, these

features are used to distinguish between varying high energy activities, such as walk-

ing, running and cycling.

Further classification of sedentary activities is performed based on the static com-

ponent of the acceleration signal which indicates the orientation of the device. This

information is only useful if one also knows the orientation of the device relative to

the orientation of the user. This information is obtained whilst the user is performing

dynamic activities (for which activity the orientation of the user’s body is relatively

well known) and updated regularly to account for the changing orientation of the

phone as it is being used by its owner.

3 Trials Performed

Two separate trials were conducted to assess the performance of the PA monitor. In

initial short technical trials the performance of the physical activity algorithms were

assessed and trial results were used to fine-tune the algorithms. At present these algo-

rithms are being employed in a larger study which also assesses the mood of the user.

Fig. 2. GUI used for trials in Limerick.

The first trial took part in the University of Limerick, Ireland and entailed the

monitoring of prescribed activities organized in a protocol lasting around half an hour.

Six healthy individuals (5 males, 1 female) went through a range of activities which

can be found in Table 1. The combined mean age of all participants was 30.6 years.

Activities recorded included: sitting, standing, walking at the subject’s comforta-

ble pace on a corridor, cycling on an indoor bike, treadmill walking at 5km/h &

6km/h, jogging at 8km/h, and finally running on a treadmill at 9.6km/h. A total of 327

minutes of data were collected using three Samsung Galaxy S phones per subject,

109

which included a central controller, and two clients. Each subject was asked to place a

phone in their right and left pants pockets. Both phones were controlled remotely via

Bluetooth by the central controller. This program could issue commands to the client

PA monitors including facilitating a synchronization request between devices. For

example, if the individual performs an activity beyond the scope of the trial, the ob-

server could issue a synch request when the subject started the next scripted activity.

Both smartphones placed in the subject’s pockets, sent real-time activity information

back to the controller. Using Matlab, the data was labeled for each activity performed

and processed to obtain a confusion matrix showing the rates of correct and incorrect

classification. In case of an incorrect classification, the confusion matrix also indi-

cates which activity was incorrectly inferred by the PA monitor. The obtained confu-

sion matrix, which is depicted in Table 1, shows that correct classification rates lie

between 82% and 91% for all activities other than sitting. Sitting is misclassified as

lying as for both activities the phone (which is in the pants’ pocket) is in the exact

same orientation. This shortcoming can be overcome by also measuring trunk orienta-

tion which is measured by the aforementioned sensor for heart rate and breathing rate.

Although this feature was beyond the scope of the described trials, use will be made

of the trunk orientation in the final ICT4Depression system. The reader should also

note that all rows sum to a likelihood of 1, apart from the row describing the Stand

activity. This is due to the fact that the algorithms use an extra ‘Transition’ stage

which indicates that the state machine is in between two of the listed activities. This

only affects the Stand activity and occurred in 9% of the time.

Table 1. Confusion Matrix.

Lie Sit Stand Walk Run Cycle

Lie N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A

Sit 1 0 0 0 0 0

Stand 0 0 .91 0 0 0

Walk 0 0 0 0.86 0.14 0

Run 0 0 0 0.13 0.85 0.02

Cycle 0 0 0 0.01 0.17 0.82

Further trials are currently underway at the VU University, Amsterdam, The

Netherlands. The goal of this study was testing the feasibility of wearing the devices

(mobile phone plus aforementioned chest strap and wrist strap) for prolonged period

of time and the ability to reliably detect the ongoing activity (specifically posture and

physical activity) from the sensors. In this study a larger cohort of volunteers are

subjected to an hour of scripted activities and consecutively to 23 hours of unscripted

activities. Thirty healthy volunteers were recruited for this study, aged 18-25. The

scripted activities consist of sitting, standing, lying, walking, cycling and tone avoid-

ance activities (see Figure 3). The tone avoidance task is an experiment in which the

user has to react to a visual stimulation by pressing a button as fast as possible. The

visual stimulation is presented as a square on a computer screen that can appear in all

four corners. The user has to react by pushing a button corresponding with the oppo-

site corner. By doing this in time, the user prevents a loud noise from sounding. This

test was used to induce a stress situation in the user, which was measured through the

use of heart rate, breathing rate and skin conductance sensors. However, this part of

the trial falls outside the scope of this paper. Subjects engage in the scripted activities

110

under supervision of the experimenter. They subsequently perform 23 hours of daily

activities without further instructions. Subjects will be monitored during this time.

During this unsupervised period, an iPod will be used by the subjects to fill out a self-

report every 30 minutes. They rate how they felt, what they did, where they were and

with who and how much time (in %) they spent on lying, sitting, standing, walking

and biking.

Fig. 3. Overview of elements assessed during the trials at the VU University.

Data analysis for these trials so far has focused on the physical activity aspects

performed as part of the ‘Regular Daily Activities’ and the ‘Standardized Physical

Activities’ as defined in Figure 3. This yields incomplete yet modestly encouraging

confusion matrices as depicted below in Table 2 and Table 3. Note that ‘Climbing

Stairs’ is not currently identified as a separate category in the physical activity algo-

rithms and that ‘Recovery’ is a period of sitting.

Table 2. Confusion Matrix for User 03.

Lie Sit Stand Walk Cycle

Sit 0.46 0.47 0.06 0.01 0

Walk 0 0 0.01 0.98 0.01

Cycle 0 0 0 0.66 0.34

Table 3. Confusion Matrix for User 04.

Lie Sit Stand Walk Cycle

Sit 1 0 0 0 0

Walk 0 0 0 0.98 0.02

Cycle 0 0 0 0.15 0.85

The results in above tables show that the difference between static (lying, sitting,

standing) and dynamic activities (walking, cycling) is accurately identified by the

algorithms. For user 03, the sitting activity is often confused with standing and lying

due to the fact that this particular sitting activity was a Recovery activity which took

place while the participant sat on an exercise bike. As the physical activity algorithms

111

assume that both upper legs are horizontal, the sitting activity on the exercise bike is

not identified correctly. The identification of the cycling activity for user 03 shows

that further features may be needed to identify the difference between walking and

cycling accurately.

For user 04 results show good identification rates. Although sitting and lying are

confused 100% of the time, the trunk orientation of the user would give a potentially

perfect feature to correctly identify sitting. The identification of static versus dynamic

activities is 100% for this participant and the correct identification of walking and

cycling 98% and 85% respectively. Similar to user 03, the correct identification of

cycling is still rather low whereas the correct identification of walking is similar at

98%, which suggests that the algorithms could be improved by fine-tuning the identi-

fication of cycling. As data analysis of these trials is ongoing, more extensive results,

also including the other activities performed during the trial, will be published in a

subsequent paper.

4 Conclusions

This paper outlines the use of mobile phones in the treatment of depression as a

means of communication with the user, presentation of the treatment modules, sensor

data gatherer and physical activity monitor in its own right. The focus of this paper

was on the latter and two physical activity monitoring trials performed as part of the

ICT4Depression project are described. The inherent challenge in measuring physical

activity with a sensor whose orientation is not known, is addressed through a data

transformation from device-fixed coordinates to world-fixed coordinates through the

use of an approximated gravity vector. The world-fixed acceleration signal is then

used to apply thresholding based algorithms to the identification of various activities.

Preliminary results show that the phone can lead to a reasonable estimate of user

activity although it is also clear that further work is needed to obtain accuracies simi-

lar to these obtained with traditional sensors.

References

1. Andrews et al: Utilising survey data to inform public policy: comparison of the cost-

effectiveness of treatment of ten mental disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, (2004)

184, 526-33

2. Ströhle, A.: Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders, J Neural Transm,

(2009) Vol. 116, pp. 777–784.

3. Blumenthal J. A., Babyak M. A., Moore K. A. et al.: Effects of exercise training on patients

with major depression. Arch Int Med (1999) 159:2349–2356.

4. Maed et al.: Exercise for depression, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews ,(2008),

Issue 4. Art. No.: CD004366. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub3.

5. Manohar, C., Mc Crady, S., Fujiki, Y., Pavlidis, I. and Levine, J.: Laboratory evaluation of

the accuracy of a triaxial accelerometer embedded into a cell phone platform for measuring

physical activity. 2010 Experimental Biology meeting (2010)

6. Bieber, G., Voskamp, J., and Urban, B.: Activity Recognition for Everyday Life on Mobile

Phones. UAHCI '09 Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Universal Access

112

in Human-Computer Interaction. Part II: Intelligent and Ubiquitous Interaction Environ-

ments. (2009)

7. Bieber, G., Koldrack, P., Sablowski, C., Peter, C., Urban, B.: Mobile physical activity

recognition of Stand-Up and Sit-Down Transitions for User Behavior Analysis. Petra

(2010).

8. Crouter, S. E, Clowers, K. G., Basset, D. R.: A novel method for using accelerometer data

to predict energy expenditure. J. Appl Physiol (2006) 100: 1324-1331

113