ERP-BASED SME BUSINESS LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

Karoliina Nisula

Department of Business Information and Logistics, Tampere University of Technology,

Korkeakoulunkatu 10, Tampere, Finland

Keywords: Business Education, Business Simulation, Learning Environment, ERP, SME.

Abstract: Small and medium size enterprises are an important and growing part of the economy. They lack an

adequately skilled workforce. Higher education is claimed to provide students with theoretical knowledge

rather than skills. Enterprise resource systems, business simulation games and the practice enterprise model

are all practical, experiential learning environments. Each of them solves different learning challenges but

does not provide a comprehensive learning environment. This paper presents a simulated learning

environment that merges the three environments together, allowing students to learn the daily operations of

SMEs in a practice-focused manner. In addition, the instructor can create learning situations appropriate for

the learning objectives at hand. The paper describes experiences of the first pilot from both the student and

the teacher perspective. An initial evaluation shows positive learning outcomes on the long-term

memorizing of declarative knowledge among the low and average students.

1 INTRODUCTION

Small and mid-size enterprises (SMEs) are an

important and a growing part of the economy. They

need skilled employees that are work-ready when

they are hired (Woods and Dennis 2009). Higher

education is claimed to produce graduates who have

good theoretical knowledge but lack practical skills

(Martin and Chapman 2006, Holden, Jameson and

Walmsley 2007). Regardless of the long term

efforts to bring education closer to the business,

there still seems to be a gap between the skills of the

business graduates and the requirements of business

life (Jackson 2009).

“Rich environments for active learning” are

broad instructional systems that stimulate study

within authentic contexts and create a feeling of

knowledge building communities (Grabinger and

Dunlap 1995). They utilize interdisciplinary learning

activities with realistic tasks.

This paper presents an active learning

environment that supports the learning of the skills

needed in SMEs. It is based on experimental

learning theory that views learning as a continuous

and iterative cycle of concrete experience, reflection,

conceptualization and testing the concepts in new

situations (Kolb 1984).

Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems are

used for acquiring the practical experience

(Targowski and Tarn 2006). Business simulation

games are also experiential learning environments

(Lainema 2009). Another, less IT-focused learning

environment is the practice enterprise model, which

aims at teaching entrepreneurship skills through a

business-to-business network where student teams

run simulated SME companies (Kallio-Gerlander &

Collan, 2007).

These learning environments are used to

accomplish different business learning objectives

(Nisula and Pekkola 2011). ERP systems focus on

IT skills and business process understanding (Jaeger,

Rudra, Aitken, Chang and Helgheim 2011) whereas

business simulation games focus on strategy and

decision-making (Faria, Hutchinson, Wellington and

Gold 2009). The practice enterprise model

emphasizes entrepreneurship, teamwork and

communication (Kallio-Gerlander and Collan 2007).

This paper argues that the learning environments

should be combined into one to promote all skills at

the same time. The paper presents the new combined

SME business learning environment, and reports an

initial evaluation of its success.

2 SME BUSINESS LEARNING

ENVIRONMENT

ERP systems give a good technical environment for

233

Nisula K..

ERP-BASED SME BUSINESS LEARNING ENVIRONMENT.

DOI: 10.5220/0003893202330238

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2012), pages 233-238

ISBN: 978-989-8565-07-5

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

hands-on learning of different disciplines and

business IT-systems. They illustrate the integration

between different business processes in practice. On

their own, however, their pedagogical benefits are

limited (Seethamraju 2011). They remain only a tool

and need a case study to work on (Markulis, Howe

and Strang 2005).

Business simulation games contain a dynamic

and interactive case. They are widely used for

learning active decision-making and teamwork

(Faria et al. 2009). They typically focus on top

management strategic decision-making or a specific

business operation. They lack the SME perspective

and a view of day-to-day operations. Many business

simulation games utilize the ERP mindset or ERP-

like system and some are even built on a commercial

ERP system (Léger 2006, Ben-Zvi 2007). The

challenge of business simulation games, however,

lies in modelling the real life situations without

oversimplifying them (Hofstede 2010, Goosen,

Jensen and Wells 2001).

In the practice enterprise model, the students

work in a virtual SME company without actual

transfer of goods or money. Unlike business

simulation games, the practice enterprise model does

not have pre-planned scenarios or contain an

element of competition. The business environment is

provided by an administrator who acts as the

authorities, the bank, the insurance company, etc.

The students trade with other similar student-run

enterprises (Kallio-Gerlander and Collan 2007). The

aim is to form customer-supplier-relationships,

negotiate agreements and market to other virtual

companies run by students.

The practice enterprise model lacks extensive

raw material and consumer markets. The learning

situations arise mostly from the student company

cooperation. The practice enterprise model is strong

on practical day-to-day SME operations and

interaction between real people. But as there is no

consumer market to create the initial demand, the

trade between student enterprises soon becomes

artificial (Santos 2006, Miettinen and Peisa 2002).

Jackson (2009) and Fernald, Solomon, &

Bradley (1999) have investigated industry-relevant

business competencies. Nisula and Pekkola (2011)

compared their findings with the learning goals of

the three experiential learning environments to find

that an optimal learning environment combines

features and benefits of all three.

3 SYSTEM OVERVIEW

The core of the SME business learning environment

is an open source ERP system Pupesoft used by

commercial SME companies (Devlab Oy). There are

three layers in the environment: The external layer is

visible to the general public. The internal layer

contains the activities inside each company and it is

run in the ERP system. The system layer contains

the data traffic caused by transactions between the

companies.

3.1 External Layer

The external layer of the learning environment is

built with web-pages. It is a fictitious market area

with providers of basic infrastructure: real estate,

electricity, telephones, insurance, transportation and

health services. The raw market consists of

wholesalers with a wide product offering. The

students start and run their companies in this

environment.

The media of the market area is a web

publication that contains imaginary local news as

well as real-life external news. A virtual online

banking provides financing. The learning

environment’s tax authorities are accessed with an

electronic tax account which is a replica of the

official Finnish electronic tax account (Finnish tax

administration 2009).

3.2 Internal Layer

All companies run their internal operations in the

Pupesoft ERP system. The system structure is

illustrated in figure 1. The ERP systems of the

various student companies, support companies, bank

and the tax officials appear separate to the end users,

but they reside in the same database. Access is

managed with user rights and profiles.

Figure 1: The learning environment database structure.

3.2.1 User Roles and Profiles

There are three user roles in the database: student,

teacher and administrator. The profiles assigned to

Pupesoft ERP

Business

game

Teacher

reporting

Bank

Tax account

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

234

these roles define which activities are available to

each user.

The student profile is adjusted to the students’

skills and learning goals. The profile grows as the

student’s learning increases.

The teacher profile enables monitoring the

students’ learning process through standard ERP

reports and user statistics.

The administrator sets up the companies and the

user accounts, sets the ERP parameters and acts as a

help desk on technical problems. In addition, he/she

runs the learning environment acting as the banker

and managing the support companies. He/she

communicates through different e-mail aliases to

create the illusion of communicating with several

companies

.

3.2.2 The Business Game Element

The business game element is administered in the

ERP system. It e-mails automated consumer

purchase orders to the student companies. The

frequency and intensity of the purchase orders can

be adjusted to emulate the market fluctuations of the

consumer market.

The business game element produces two types

of purchase orders: Random orders are created

regardless of the student company’s business

performance. The amount of work and profit are

equal in all student companies. Routine orders are

related to how professionally the student company is

running its business operations. A well performing

student company gets financially more valuable

orders than another company with a lower

performance

.

3.3 System Layer

The system layer transfers financial data between

ERP and bank systems. The data transfer creates a

closed ecosystem with double-entry book-keeping.

Every external transaction is recorded in two

companies. This provides the basis for the business

game indicators as it populates the companies’ ERP

systems with income and cost data. It also enables

the administrator and the facilitating teachers to stay

up-to-date on the student companies’ activities. The

facilitating teachers get company reports based on

transactional data rather than the students’

interpretation of the situation.

4 EVALUATION

The first version of the learning environment was

piloted in the Tampere University of Applied

Sciences (TAMK) School of business and services

in 2010-2011. Before this pilot, the practice

enterprise model had been in use since 2005. The

pilot was run with 170 business students in 17

simulated companies. 12 teams were first-year BBA

students and five teams were second-year BBA

students. The student teams started a simulated

business-to-business company and operated it for a

year. In addition to their other business studies they

worked 4-8 hours a week in their companies. The

curriculum integrated disciplinary lectures into the

student company life cycle. The teams had

supervising teachers who coached and mentored

them in the learning environment.

The learning process was based on Kolb’s

experiential learning model. The student companies

were divided into three departments of 3-4 students:

marketing, logistics and accounting. Each student

worked in a department for a period of time to gain

practical experience and reflect on that. They also

followed lectures, which helped them to

conceptualize their experiences. At the end of each

period, the department roles rotated. The students

taught each other the tasks of their new departments.

They were able to test their skills in new situations,

which, again, completed Kolb’s learning cycle. Each

student worked in all the departments during the

academic year. This gave them a full overview of a

company’s business processes (Nisula and Pekkola

2011).

The pilot was evaluated through the learning

outcomes as well as student and teacher feedback.

The evaluation was done with two groups of first

year students, each containing 117 students. The first

group, class of 2009, used the practice enterprise

model. The second group, class of 2010, used the

SME business simulation.

The learning outcome was evaluated through the

acquisition of declarative, disciplinary knowledge. It

was measured with open-end and multiple-choice

questions. The evaluation had three phases: a pre-

understanding, a mid-term and an end test. The end

test was given 3 months after the end of the

academic year in order to measure longer term

learning effects.

Feedback from the students and the teachers was

collected through web questionnaires at mid-term.

The teachers also had a face-to-face feedback

session in the end of the academic year.

4.1 Effects on Learning

Both the practice enterprise group and the simulation

ERP-BASEDSMEBUSINESSLEARNINGENVIRONMENT

235

group gained similar average scores in the pre-

understanding test (62%) and the mid-term test (70-

71%). In the long-term efforts the simulation group

scored slightly higher with 62% against the 58% of

the previous practice enterprise model group.

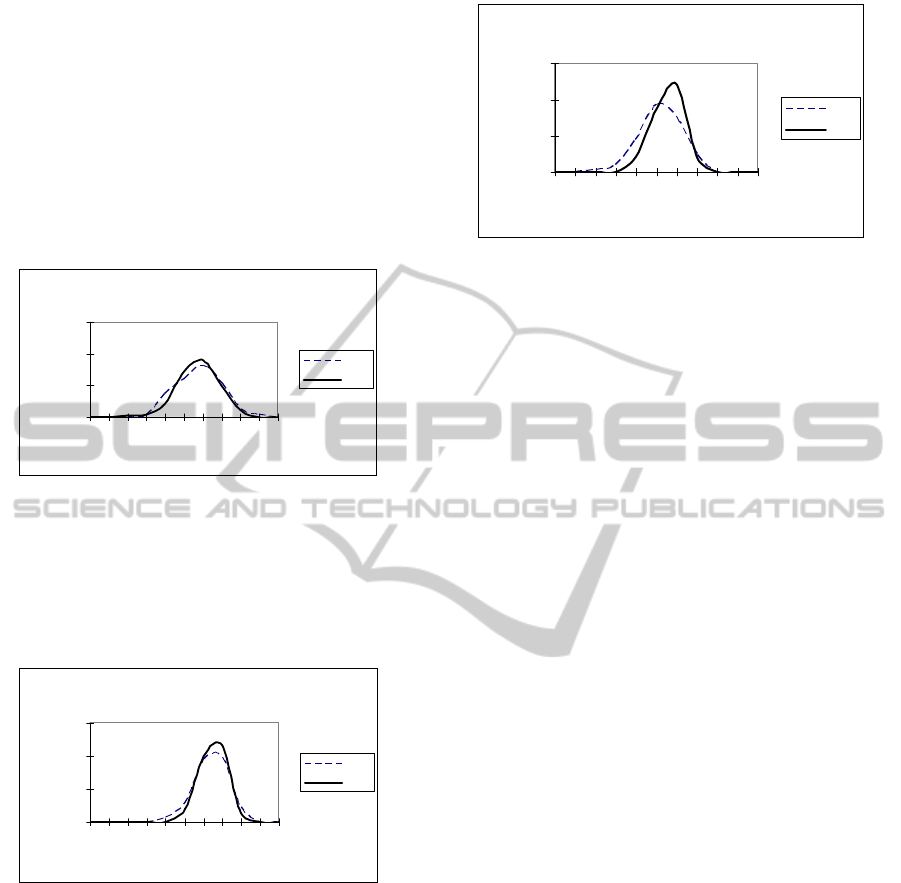

When looking at the distributions of the scores,

however, some more distinctive results can be

found. Figure 2 shows the score distribution for the

pre-understanding test in the beginning. On both

groups the score distribution follows approximately

the same bell shaped curve.

Figure 2: Score distribution on the pre-understanding test.

Figure 3 shows that at mid-year the same trend

continues. The practice enterprise group has a

slightly wider range of scores in both highs and lows

whereas the simulation groups’ scores were more

focused on the average 60-70% range.

Figure 3: Score distribution on the mid-term test.

In the figure 4, at the year end, there is a difference

between the groups. The curves are identical in the

high scores, but the low and average scores are

better in the simulation group. This seems to indicate

that the high performers score well regardless of the

learning environment where as the low and average

performers benefit from the simulation environment.

This evaluation shows some promising signs of

improvements in the long term memorizing of the

low and average performing students. However,

alone it does not provide enough evidence to show

the SME business simulation’s superiority to the

practice enterprise model.

Figure 4: Score distribution on the year-end test.

This evaluation was restricted to the learning

goals of the disciplinary expertise which is just one

learning objective among many. A study on the

efforts on other learning objectives is an interesting

area for further research.

4.2 Student Feedback

At mid-term the students were given a web-

questionnaire with a set of statements as well as

some open end questions. There were 101 responses.

The best average scores on a Likert-type scale

(1=strongly disagree, 5= strongly agree) were on

applying theory to practice and making studying

versatile (4,1). Integration between the simulation

environment and the curriculum also scored well

(3,8). Moreover, students appreciated the simulation

in creating the big picture of the business processes

(3,8). The poorest scores were on the motivational

aspect (3,2) and the uneven distribution of workload

(2,8). The uneven work load is a typical challenge in

a team-oriented learning method.

In the open-end questions the most frequently

mentioned positive sides reflect Kolb’s learning

cycle: practical, hands-on approach, combining

theory with practice and versatility, variation and

change to traditional studying methods. Also, team

work was seen as a positive factor. Critical feedback

focused mostly on the uneven distribution of work

load, simplification vs. reality, technical problems

and communication challenges.

4.3 Teacher Feedback

The supervising teachers’ feedback reflected the

students’ reaction. According to the teachers the

students had learned to use the systems quickly. On

the other hand, this learning environment seemed to

require more intensive coaching and guiding.

The teachers felt more uneasy with the IT

orientation than the students. They also found the

Pre-understanding test

0 %

20 %

40 %

60 %

0 20 40 60 80 100

score

% of all scores

2009

2010

Mid-term test

0 %

20 %

40 %

60 %

0 20406080100

score

% of all scores

2009

2010

End test

0 %

20 %

40 %

60 %

0 20406080100

score

% of all scores

2009

2010

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

236

new environment challenging because it required a

lot of general business and IT knowledge. Most of

them, however, found it motivating to learn new

things together with the students. They appreciated

the increased opportunities to combine theory with

practice by using examples of the learning

environment in their lectures. The increased

visibility to the student teams’ activities was also

mentioned as a benefit.

5 RELATED SYSTEMS

ERP systems have been used as a teaching tool for

approximately 10 years (Targowski and Tarn 2006).

ERP systems can provide a nerve system to integrate

different disciplines and remove redundancies

between them (Joseph, George 2002). Yet ERP

systems remain mechanical tools for training rather

than a comprehensive environment for deep learning

(Seethamraju 2011).

Business simulation games are widely used in

strategic management courses (Faria et al. 2009).

INDUSTRYPLAYER (Faria et al. 2009) is a global

online multiplayer game. INTOPIA (Thorelli 2001)

focuses on international business. MICROMATIC

simulates a small manufacturing company

(Washbush and Gosen 2001) whereas CYCLOAN

runs a branch office of a service company

(Scherpereel 2005). These are only a few examples

of the wide range of business simulation games.

RealGame is an example that contains some

ERP-like functionality even though it is not based on

a commercial ERP system (Lainema and Makkonen

2003). ERPSim is a combination of the SAP

environment and simulated events caused by student

teams’ business decisions (Léger 2006).

An ERP-based business simulation game is a

good learning environment for diverse simulations

that resemble running real-life operations. However,

the business simulation games tend to focus on the

top management decision making or a specific

functional area. They are not optimal in learning the

day-to-day SME operations.

6 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

RESEARCH

The main difference between the new SME learning

environment and the related systems is twofold:

First, the new SME learning environment excels the

related systems because it combines their specialized

features for an improved result. Second, it is a

flexible, comprehensive environment where the

instructor can choose how to incorporate it into

learning.

The learners become active participants in the

learning process. They repeat Kolb's learning cycle

several times and have opportunities to reflect their

experiences. In addition to simple task delivery, the

learners face unexpected, instructor created

problems that do not always have simple solutions.

The first evaluation on the learning results

indicates improvements in the long-term

memorizing of disciplinary declarative knowledge.

It is particularly interesting that the improvements

were found amongst the low and average scoring

students. However, more research is needed to

study the learning outcomes on other business skills.

Based on the feedback the new learning

environment appears to be a motivating environment

to students and teachers alike. The learning

environment requires the teachers to expand to

outside their comfort zone both professionally and

mentally. A deeper research into the effects on the

teachers’ work would be of interest.

The learning environment is still only a tool for

teaching and learning. The teachers and students

give it meaning. It is crucial that it is integrated into

other teaching and the whole curriculum.

Curriculum integration of the learning environment

is another interesting topic for future research.

REFERENCES

Ben-Zvi, T. (2007). Using Business Games in Teaching

DSS, Journal of Information Systems Education,

18(1), 113-124. Retrieved from http://www.jise.org/

Devlab Oy web-pages. Retrieved February 10, 2012, from

http://www.devlab.fi/#/pupesoft

Faria, A. J., Hutchinson, D., Wellington, W. J. & Gold, S.

(2009). Developments in Business Gaming: A Review

of the Past 40 Years, Simulation & Gaming, 40(4),

464-487. doi:10.1177/1046878108327585

Fernald, L. J., Solomon, G. & Bradley, D. (1999). Small

business training and development in the United

States, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise

Development, 6(4), 310-325. doi:10.1108/EUM00000

00006685

Finnish tax administration, Tax Account Guide. Retrieved

September 17, 2009, from ttp://portal.vero.fi/Public/

default.aspx?culture=en-US&contentlan=2&nodeid

=7882

Goosen, K. R., Jensen, R. & Wells, R. (2001). Purpose

and Learning Benefits of Simulations: A Design and

Development Perspective, Simulation & Gaming,

32(1), 21-39. doi:10.1177/104687810103200104

ERP-BASEDSMEBUSINESSLEARNINGENVIRONMENT

237

Grabinger, R. S. & Dunlap, J. C. (1995). Rich

environments for active learning: a definition,

Association for Learning Technology Journal, 3(2), 5-

34. Doi:10.1080/0968776950030202

Hayen, R. L. & Andera, F. A. (2006). Analysis of

enterprise software deployment in academic curricula,

Issues in Information Systems, VII(1), 273-277.

Hofstede, G. J. (2010). Why Simulation Games Work-In

Search of the Active Substance: A Synthesis,

Simulation & Gaming, 41(6), 824-843. doi:10.1177/10

46878110375596

Holden, R., Jameson, S. & Walmsley, A. (2007). New

graduate employment within SMEs: still in the dark?

Journal of Small Business and Enterprise

Development, 14(2), 211-227. doi:10.1108/146260007

10746655

Jackson, D. (2009). An international profile of industry-

relevant competencies and skill-gaps in modern

graduates, International Journal of Management

Education, 8(1), 85-98. doi:10.3794/ijme.81.281

Jaeger, B., Rudra, A., Aitken, A., Chang, V. & Helgheim,

B. (2011). Teaching business process management in

cross-country collaborative teams using ERP, The 19th

European Conference on Information Systems ICT

and Sustainable Service Development, June 9-11,

2011.

Jensen, T. N., Fink, J., Møller, C., Rikhardsson, P. &

Kræmmergaard, P. (2005). Issues in ERP Education

Development – Evaluation of the Options Using Three

Different Models, 2nd International Conference on

Enterprise Systems and Accounting (ICESAcc’05), 11-

12 July 2005.

Joseph, G. & George, A. (2002). ERP, learning

communities, and curriculum integration, Journal of

Information Systems Education, 13(1), 51-58.

Retrieved from http://www.jise.org/

Kallio-Gerlander, J. & Collan, M. (2007). Educating

Multi-disciplinary Student Groups in

Entrepreneurship: Lessons Learned from a Practice

Enterprise Project Retrieved May 5 2010 http://mpra.

ub.uni-muenchen.de/4331/1/MPRA_paper_4331.pdf

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as a

source of learning, Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

Lainema, T. & Makkonen, P. (2003). Applying

constructivist approach to educational business games:

Case REALGAME, Simulation & Gaming, 34(1),

131-149. doi:10.1177/1046878102250601

Lainema, T. (2009). Perspective Making: Constructivism

as a Meaning-Making Structure for Simulation

Gaming, Simulation & Gaming, 40(1), 48-67. doi:10.1

177/1046878107308074

Léger, P. (2006). Using a Simulation Game Approach to

Teach Enterprise Resource Planning Concepts,

Journal of Information Systems Education, 17(4), 441-

448. Retrieved from http://www.jise.org/

Markulis, P. M., Howe, H. & Strang, D. R. (2005).

Integrating the business curriculum with a

comprehensive case study: A prototype, Simulation &

Gaming, 36(2), 250-258. doi:10.1177/104687810427

2434

Martin, P. & Chapman, D. (2006). An exploration of

factors that contribute to the reluctance of SME

owner-managers to employ first destination marketing

graduates,

Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 24(2),

158-173. doi:10.1108/02634500610654017

Miettinen, R. & Peisa, S. (2002). Integrating School-based

Learning with the Study of Change in Working Life:

the alternative enterprise method, Journal of

Education and Work, 14(3), 303-313. doi:10.1080/13

63908022000012076

Nisula, K. & Pekkola, S. (2012). ERP-based simulation as

a learning environment for SME business. To appear

in International Journal of Management Education.

Santos, J. A. (2006). Practice Firms and Networked

Learning: Unaccomplished Potentialities, Proceedings

of the Fifth International Conference on Networked

Learning 2006, Lancaster University, Lancaster, April

10-12, 2006.

Scherpereel, C. M. (2005). Changing mental models:

Business simulation exercises, Simulation & Gaming,

36(3), 388-403. doi:10.1177/1046878104270005

Seethamraju, R. (2011). Enhancing Student Learning of

Enterprise Integration and Business Process

Orientation through an ERP Business Simulation

Game, Journal of Information Systems Education,

22(1), 19-29. Retrieved from http://www.jise.org/

Targowski, A. S. & Tarn, M. J. (2006), Enterprise Systems

Education in the 21st Century, Information Science

Publishing, Hershey, USA.

Thorelli, H. B. (2001). Ecology of International Business

Simulation Games, Simulation & Gaming, 32(4), 492-

506. doi:10.1177/104687810103200406

Washbush, J. & Gosen, J. (2001). An exploration of game-

derived learning in total enterprise simulations,

Simulation & Gaming, 32(3), 281-296. doi:10.1177/1

04687810103200301

Woods, A. & Dennis, C. (2009). What do UK small and

medium sized enterprises think about employing

graduates? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise

Development, 16(4), 642-659. doi:10.1108/146260009

11000974

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

238