DESIGNING COLLABORATIVE MULTIPLAYER SERIOUS GAMES

FOR COLLABORATIVE LEARNING

Escape from Wilson Island - A Multiplayer 3D Serious Game

for Collaborative Learning in Teams

Viktor Wendel

1

, Michael Gutjahr

2

, Stefan G

¨

obel

1

and Ralf Steinmetz

1

1

Multimedia Communication Labs - KOM, TU Darmstadt, Rundeturmstr. 10, 64283 Darmstadt, Germany

2

Institut fuer Psychologie, TU Darmstadt, Alexanderstr. 10, 64283 Darmstadt, Germany

Keywords:

Serious Games, Collaborative Learning, CSCL, Game-based Learning.

Abstract:

The concept of collaborative learning has been researched for many years. The idea of Computer Supported

Collaborative Learning (CSCL) is being investigated for more than twenty years. Since a few years, game-

based approaches like video games for learning (Serious Games) offer new fields of application. The combina-

tion of game-based learning concepts and collaborative learning may enable new application areas of CSCL.

However, the design of such games is very complex. The gameplay has to fulfill requirements of traditional

single player games (fun, narration, immersion, graphics, sound), challenges of multiplayer games (concur-

rent gaming, interaction) and Serious Game design (seamless inclusion of learning content, adaptation and

personalization). Furthermore, requirements of collaborative learning have to be considered, like group goals,

positive interdependence, and individual accountability. In this paper we describe an approach for game-based

collaborative learning using multiplayer Serious Games. We developed an approach for a collaborative 3D

multiplayer game fostering collaborative behavior as a foundation for collaborative learning in teams using

games. First evaluations of a prototype for 3-4 players showed that the game enables a collaborative gameplay

and fosters collaborative behavior. This may allow us to use a game-based CSCL approach to combine the

advantages of game-based learning with those of collaborative learning in future.

1 MOTIVATION

Collaborative learning is a learning concept which is

broadly accepted in various institutions of education

today. For more than twenty years, the idea if using

computers to support collaborative learning is being

investigated. However, most of the research in the

field of Computer Supported Collaborative Learning

(CSCL) deals with e-learning applications or how to

use (new) medias like the Internet or email to sup-

port collaborative learning. In recent years, game-

based learning has become an alternative and a sup-

plement to traditional learning concepts. Various re-

search (Gee, 2003), (Prensky, 2001) has shown that

Serious Games offer a new field of application which

can be utilized to support learning in many fields

(learning, sports & health, political education, etc.).

Today there is a multitude of Serious Games for learn-

ing addressing different target groups. Yet most of

those games are for single player use. Only a limited

number of Serious Games have been designed with

multiplayer support due to the lack of concepts for

multiplayer Serious Games.

The combination of game-based learning concepts

in Serious Games with collaborative learning may

enable new methods of CSCL. The design of such

games, however, is challenging. The gameplay has to

fulfill requirements of traditional single player games

(fun, narration, immersion, graphics, sound), chal-

lenges of multiplayer games (concurrent gaming, in-

teraction) and Serious Game design (seamless in-

clusion of learning content, adaptation & personal-

ization). Furthermore, requirements of collaborative

learning have to be considered, like communication

and social skills or a proper group setup.

In this paper we describe an approach for col-

laborative multiplayer Serious Games which enable

game-based collaborative learning. As a first step we

want to develop a game design for multiplayer Se-

rious Games fostering collaborative behavior among

199

Wendel V., Gutjahr M., Göbel S. and Steinmetz R..

DESIGNING COLLABORATIVE MULTIPLAYER SERIOUS GAMES FOR COLLABORATIVE LEARNING - Escape from Wilson Island - A Multiplayer 3D

Serious Game for Collaborative Learning in Teams.

DOI: 10.5220/0003899801990210

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2012), pages 199-210

ISBN: 978-989-8565-07-5

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

players. The game design takes into account both the

design challenges of multiplayer games and of collab-

orative learning. Our approach attempts to fulfill the

requirements for cooperative work as a prerequisite

of collaborative learning while following the design

guidelines for collaborative games found in literature.

We use this approach to design a 3D multiplayer

Serious Game with a collaborative gameplay as a

foundation for collaborative learning. First evalua-

tions of a prototype for 3-4 players showed that the

game enables a collaborative gameplay and fosters

collaborative behavior (teamplay, coordination be-

tween players, communication).

The paper is structured as follows: In Section 2,

we discuss the state of the art, in Section 3, we de-

scribe our approach for game-based CSCL using mul-

tiplayer games. In Section 4, we present a prototype

for our approach, followed by a discussion of first

results in Section 5 based on a user centered study.

We conclude this paper with a brief summary in Sec-

tion 6.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Game-based Learning

Game-based learning is one of the older fields of Se-

rious Games. (Prensky, 2001) explained, why using

games for learning can be a promising approach. He

argues, that motivation is a key factor for learning,

and games can provide the necessary motivation sug-

gesting to combine gaming technology with learning

concepts. (Gee, 2003) argued that

”... schools, workplaces, families, and aca-

demic researchers have a lot to learn about

learning from good computer and video

games. Such games incorporate a whole set

of fundamentally sound learning principles,

principles that can be used in other settings,

for example in teaching science in schools.”

An interesting overview of games used in educational

research is given by (Squire, 2003) who describes the

various forms and genres of games already being used

in education, especially in classroom so far. Those are

mainly ’Drill-and-practice’ games, simulations, and

strategy games. ’Drill-and-practice’ games are mostly

utilized for learning by enriching factual recall exer-

cises in a playful way. Simulation games can be used

to simplify complex systems, i.e. laws of physics,

ecosystems (Sim Earth

1

), or politics. On the other

1

www.maxis.com

hand, high fidelity simulations can be used for real-

istic training scenarios as often used by military or

e.g. flight simulators. However, the number of profes-

sionally created Serious Games today is quite small.

As Zyda states (Zyda, 2007), ”Today’s game indus-

try will not build a game-based learning infrastructure

on its own. It got killed in the early days of edutain-

ment”. This may be true or not, according to IDATE

2

,

the global Serious Games market in 2010 was only 1.5

billion EUR, whereas the entire video gaming market

in 2009 was about 60 billion $. However, although

a large number of today’s Serious Games are created

in universities with naturally smaller budgets, accord-

ing to IDATE ”... we can expect to see the business

worlds interest in serious games increase around 2013

...”

The focus of educational games in the last decade,

especially concerning learning games, was mainly on

simple simulation games (TechForce

3

) or learning ad-

ventures (Geographicus

4

, Winterfest

5

). Those games

were created as a playful alternative to learning facts

by heart or to provide a playful environment learning

through trial and error (e.g. physics games).

However, adventures are traditionally single

player games and the majority of simulation games

are single player games, too, especially in the Serious

Games sector. This means a limitation for the use of

those games.

2.2 Collaborative Learning

The concept of collaborative learning is being dis-

cussed among educators for decades. Collaborative

learning is used in schools today in various forms,

like joint problem solving in teams, debates, or other

team activities. According to (Dillenbourg, 1999),

one definition for collaborative learning is ”a situation

in which two or more people learn or attempt to learn

something together”. (Roschelle and Teasley, 1995)

define collaboration as ”a coordinated, synchronous

activity that is the result of a continued attempt to

construct and maintain a shared conception of a prob-

lem”. Compared to Dillenbourg’s definition of coop-

eration (Dillenbourg, 1999),

”In cooperation, partners split the work, solve

sub-tasks individually and then assemble the

partial results into the final output”,

this is much more than just cooperation. Dillen-

bourg defines collaboration as follows: ”In collabora-

2

http://www.reports-research.com/168/d/2010/08/16/id

ate-serious-games-a-10-billion-euro-market-in-2015/

3

www.techforce.de/

4

www.braingame.de

5

www.lernspiel-winterfest.de/

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

200

tion, partners do the work ’together’ ”, (Dillenbourg,

1999).

The idea of collaborative learning is to make

learners interact in particular ways such that certain

learning mechanisms are triggered. Therefore, sev-

eral mechanism to enhance the probability of these

interactions to occur are currently being researched.

These are according to (Dillenbourg, 1999):

• Setup of Initial Conditions: (Group size, gender,

same viewpoint vs. opposing viewpoint).

• Role-based Scenario: Problems which cannot be

solved with one type of knowledge.

• Interaction Rules: Free communication vs. pre-

defined communication patterns (see also (Baker

and Lund, 1997)).

• Monitoring and Regulation of Interactions:

Need for specific tools for the teacher.

(Johnson and Johnson, 1994) identified five essen-

tial elements which foster cooperative work in face-

to-face groups. These are often cited as ”five com-

ponents that are essential for collaborative learn-

ing” (Zea et al., 2009):

• Positive Interdependence: Knowing to be linked

with other players in a way so that one cannot suc-

ceed unless they do.

• Individual Accountability: Individual assess-

ment of each student’s performance and giving

back the results to both the group and the indi-

vidual.

• Face-to-Face Promotive Interaction: Promot-

ing each other’s success by e.g. helping, encour-

aging and praising.

• Social Skills: Interpersonal and small group skills

are vital for the success of a cooperative effort.

• Group Processing: Group members discussing

their progress and working relationships.

For the success of collaborative learning, both with or

without the use of a computer, it is essential that the

collaborative learning environment enables and fos-

ters those elements.

2.3 Computer Supported Collaborative

Learning

The idea of using computers to support learning arose

in the 1980s, with computers as tools mainly for writ-

ing, and organizing. In the 1990s, with the Internet

and network technologies arising, new ways of com-

munication and collaboration emerged. Intelligent tu-

toring systems were designed. However, the main

task for a computer was being a medium for commu-

nication, in form of email, chat, forums, etc. (Stahl

et al., 2006). In recent years, many forms of CSCL

have been designed and used in curricula at schools.

Collaborative writing (Onrubia and Engel, 2009) is

one such form, where learners collaboratively create a

document using computer technologies. Furthermore,

today many web technologies are used for CSCL, like

Forums or Wikis (Larusson and Alterman, 2009).

2.4 Game-based Collaborative Learning

With the upcoming of Virtual Worlds like Second

Life

6

or private virtual worlds like IBM Virtual Col-

laboration for Lotus Sametime

7

, research also fo-

cused on using those as collaborative learning envi-

ronments (Nelson and Ketelhut, 2008). As they are

very popular and often freely available, also Mas-

sively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOG) have been

used as environments for collaborative learning sce-

narios. (Delwiche, 2006) held online courses in

the MMOG Everquest

8

and Second Life teaching

about videogame design and criticism. (H

¨

am

¨

al

¨

ainen

et al., 2006) tried to find out whether the charac-

teristic features of 3-D games can be used to cre-

ate meaningful virtual collaborative learning environ-

ments. (Zea et al., 2009) presented design guide-

lines enabling incorporation of features of collabora-

tive learning in the videogame development process

based on the five essential elements for collaborative

learning stated by Johnson & Johnson. (Voulgari and

Komis, 2008) investigated the design of effective col-

laborative problem solving tasks within MMOGs, and

(Rauterberg, 2002) performed a test about collabora-

tion in MMOGs finding out that communication is es-

sential for effective collaboration. An approach for a

3D collaborative multiplayer Serious Game for learn-

ing with freely definable learning content is presented

in (Wendel et al., 2010).

2.5 Game Design

Computer game design is a well researched field, with

lots of literature available (Crawford, 1984), (Salen

and Zimmerman, 2004). Those books cover topics

like game goals, how to create immersion, graphics,

sound, network technologies. In the field of Seri-

ous Games there are additional challenges to game

design. Serious Games for learning not only have

to fulfill the same requirements as other games, but

6

http://secondlife.com

7

http://www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/2783

1.wss

8

www.everquest.com

DESIGNINGCOLLABORATIVEMULTIPLAYERSERIOUSGAMESFORCOLLABORATIVELEARNING-Escape

fromWilsonIsland-AMultiplayer3DSeriousGameforCollaborativeLearninginTeams

201

they also have to equip the player with knowledge.

(Kiili, 2005) proposed a gaming model for educa-

tional games based on flow theory by (Csikszentmi-

halyi, 1991). (Said, 2004) proposed a model for chil-

dren, which presents five factors necessary to create

an engaging experience for children. These factors

are ’Simulation interaction’, ’Construct interaction’,

’Immediacy’, ’Feedback’, and ’Goals’. (Kelly et al.,

2007) describe how to create a Serious Game for

teaching focusing both on traditional gameplay ques-

tions and on the integration of learning tools. To solve

this problem, (Wendel et al., 2011) proposed a set

of guiding principles for Digital Educational Games

design focusing on the seamless integration of learn-

ing content in Serious Games. (Manninen and Korva,

2005) proposed an approach for puzzle design for col-

laborative gaming along with an implementation in

the collaborative game eScape. (Harteveld, 2011) de-

scribes various aspects to be considered when design-

ing Serious Games. The book covers gaming founda-

tions, how to define the real world problem, the ne-

cessity to define the purpose of the game, and gives

tips about interesting choices during Serious Games

design.

A different approach for collaborative game de-

sign is made in (Zagal et al., 2006). They analyzed

a collaborative board game and identified important

lessons learned and pitfalls when creating collabora-

tive games. They finally try to convert their findings

on the design of collaborative computer games:

• Lesson 1: To highlight problems of competitive-

ness, a collaborative game should introduce a ten-

sion between perceived individual utility and team

utility.

• Lesson 2: To further highlight problems of com-

petitiveness, individual players should be allowed

to make decisions and take actions without the

consent of the team.

• Lesson 3: Players must be able to trace payoffs

back to their decisions.

• Lesson 4: To encourage team members to make

selfless decisions, a collaborative game should be-

stow different abilities or responsibilities upon the

players.

• Pitfall 1: To avoid the game degenerating into one

player making the decisions for the team, collabo-

rative games have to provide a sufficient rationale

for collaboration.

• Pitfall 2: For a game to be engaging, players

need to care about the outcome and that outcome

should have a satisfying result.

• Pitfall 3: For a collaborative game to be enjoyable

multiple times, the experience needs to be differ-

ent each time and the presented challenge needs

to evolve.

3 OUR APPROACH

As shown in the previous section, the concept of

collaborative learning is known for many years and

has also been combined with computer technology

(CSCL). Furthermore, many game-based learning ap-

plications or Digital Educational Games (DEGs) are

being used for various fields in education. However,

to the best of our knowledge, there are no multiplayer

Serious Games for collaborative learning so far.

In order for collaborative learning to take place

in a game-based learning environment, the Serious

Game must fulfill the requirements for collaborative

learning. As we showed in Section 2, there are sev-

eral requirements for collaborative learning to take

place (e. g. requirements of cooperative working,

see (Johnson and Johnson, 1994)). Furthermore, in

a Serious Game, requirements regarding game design

and learning content integration have to be met. In our

approach, we integrated the requirements for cooper-

ative working into the game design to create a Serious

Game for collaborative learning based on one of the

most popular Serious Gaming genres for learning: 3D

virtual worlds.

Resulting from the literature review shown in the

previous section, we developed the following concept

ideas. They are designed in a way such that they

match the necessary elements for cooperative work-

ing of (Johnson and Johnson, 1994): (Positive inter-

dependence, Individual Accountability, Face-to-Face

Promotive Interaction, Social Skills, and Group Pro-

cessing). Furthermore, they take into account the

lessons and pitfalls of (Zagal et al., 2006) as described

in Chapter 2 and the design guidelines stated in (Zea

et al., 2009).

• Common Goal/Success: The goal of the game

should be designed in a way such that success

means success for all players.

• Heterogeneous Resources: Each player should

have one unique tool or ability enabling him/her

to perform unique tasks in the game which other

players cannot perform, e.g. only the player with

the axe can fell palms in order to get wood for

building the hut, the raft or for fire.

• Refillable Personal Resources: In order to cre-

ate a certain tension, there should be certain re-

fillable resources (e.g. a health or hunger value)

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

202

which slowly deplete automatically or when play-

ers act dangerously. Furthermore, they should be

influenceable in a way such that players can help

each other (e.g. food could be gathered by one

player and then be given to another player to pre-

vent him/her from starving).

• Collectable and Tradable Resources: There

should be resources in the game world necessary

for the players to win the game. These resources

should be tradable between players in order to cre-

ate space for decisions to negotiate or collaborate

(e.g. giving a resource to another player for the

common good of the team or trading resources be-

tween players).

• Collaborative Tasks: If all tasks could be solved

by one player, there would be no need to collab-

orate. So there should be tasks which are solv-

able only if players act together. Those tasks may

include the heterogeneous resources described

above to create a need for certain players to partic-

ipate in team tasks. This may cause a need for dis-

cussion among players when the group depends

on one individual.

• Communication: It has been shown that commu-

nication is vital for collaborative learning. So the

game should provide a way for players to com-

municate (e.g. chat system, voice communica-

tion). While voice communication might be easier

for most players, a text-based chat system might

be easier to evaluate. Also a third party tool for

communication like Skype, TeamSpeak or Mum-

ble could be used.

• Ingame Help System: The game should provide

help to the players when they are stuck. The eas-

iest way is a popup when players fail a task or it

takes them too long to solve it. Furthermore, the

help system should be triggerable by the players.

A more sophisticated but also more immersive

way is to include help in the game itself, e.g. by

having ingame characters (NPCs) providing help

when needed.

• Scoreboard: A scoreboard should show both in-

dividual efforts and team efforts at the end of the

game. This may help players judge the overall

success (e.g. by comparison with other teams

or previous attempts) and each player’s contri-

bution to the team performance. The individual

score may function as a motivator for selfish ac-

tions which helps to make collaboration not self-

evident.

• Trading System: Players should be able to trade

items among each other. This creates space for

decisions for or against collaboration.

3.1 Reference to Related Work

As a next step we want to discuss our concept in rela-

tion to the lessons and pitfalls of Zagal et al.:

Regarding Lesson 1: By having an individual

score board for each player, we create a competi-

tive element. Individual scores can sometimes be

achieved by helping the group (e.g. when participat-

ing in solving a task together), or they can be selfish

(e.g. when gathering resources).

Regarding Lesson 2: By the nature of the game

(3D third person, open environment), each player may

move and act freely. No player is forced to perform

any action, although some actions are not possible

without other players’ consensus.

Regarding Lesson 3: The results of decisions are

always visible to the players as they are immediate.

A player may e.g. decide to help solving a task or

to gather resources. If he/she decides not to help, the

group might not be able to complete the task, which

will slow them down. The player, however, will have

a personal resource refilled.

Regarding Lesson 4: By providing players with

heterogeneous resources (tools), each player has a dif-

ferent ability and responsibility.

Regarding Pitfall 1: The nature of a 3D 3rd Per-

son game makes it very difficult for one person to

fell decisions for all players, however leader roles will

certainly be possible and relevant.

Regarding Pitfall 2: As all players either win or

lose together, each player should care about the out-

come assumed he/she has the proper motivation to

play at all. Such a motivation is provided by the nar-

rative background story, which creates a similar mo-

tivation to ’win’ the game as in any other game.

Regarding Pitfall 3: Although the core game it-

self will not change, when played repeatedly, the free

game world and the free sequence of available ac-

tions can create completely different progressions of

the game in different runs. Also, playing with dif-

ferent players will be a completely different expe-

rience for a player than a previous game. Further-

more, the difficulty of the game can be influenced by

a teacher/trainer both before and during runtime, so

that more experienced players will still find the game

challenging.

Finally, we discuss our concept in relation to

the cooperative working requirements by Johnson &

Johnson:

Positive Interdependence: As many tasks are

only solvable if players work as a team, we think

players will realize quickly that they cannot succeed

alone.

Individual Accountability: By introducing an

DESIGNINGCOLLABORATIVEMULTIPLAYERSERIOUSGAMESFORCOLLABORATIVELEARNING-Escape

fromWilsonIsland-AMultiplayer3DSeriousGameforCollaborativeLearninginTeams

203

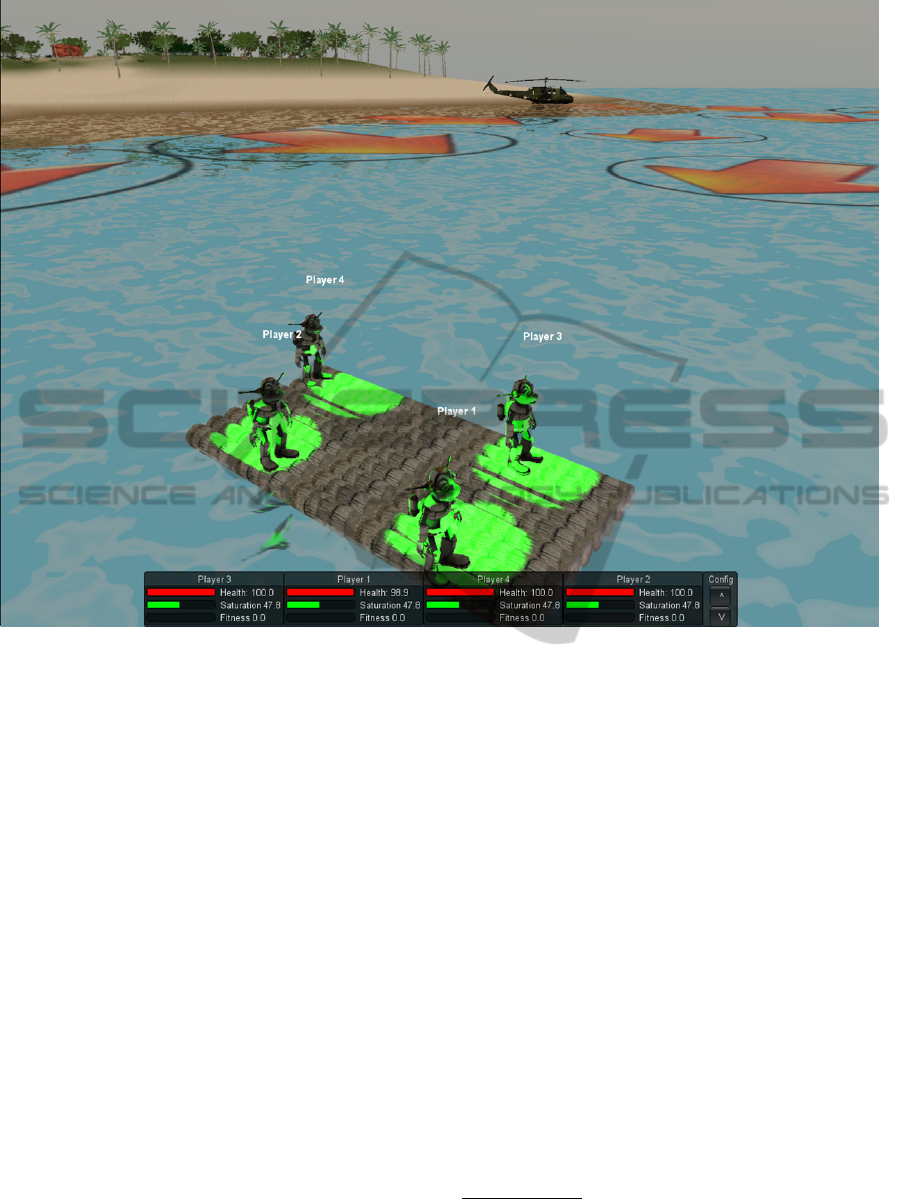

Figure 1: Four players steering the raft together.

individual scoreboard, the game can assess each play-

ers personal performance. As the scoreboard is visible

to the whole group, the results are given back to both

the group and the individual.

Face-to-Face Promotive Interaction: Although

the game itself does not encourage promoting behav-

ior like encouraging or praising fellow players, the

game enables players to do so. Players can help, en-

courage, or praise other players via chat. Further-

more, they can help other players through their ac-

tions. A player who decides to help his/her fellow

players, will significantly improve his/her chances of

success.

Social Skills: We believe that interpersonal and

small group skills can be trained by use of this game if

observed and guided by a teacher. The game provides

lots of opportunities for practicing social skills both

in speech (chat) or behavior (gameplay).

Group Processing: Again, this is not a process

created through the game itself, but the game pro-

vides the players with the possibilities to discuss their

progress and relationships (chat) and to reflect on

them (scoreboard).

4 ESCAPE FROM WILSON

ISLAND

Escape from Wilson Island (EFWI) (see Figure 1) was

created using the Unity3d

9

game engine. For the first

prototype we used standard assets which are freely

available for Unity3d. The game is scripted in C#.

The game can be classified as a 3rd person role-

play game (RPG) with limited roleplaying aspects.

The focus of the game is the collaborative gameplay

itself, including social skills like teamwork, coordina-

tion, or communication.

As we wanted to create a collaborative game for

a small group of up to four players, we chose a se-

cluded game world in form of an island. This allows

us to create natural looking boundaries (the sea) for

the players’ ’playground’. Most of today’s Massively

Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (World Of

Warcraft, Guild Wars

10

, etc.) or Virtual Worlds (Sec-

ond Life) are played in a 3D 3rd person perspective.

9

www.unity3d.com

10

www.guildwars.com

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

204

Figure 2: Players carrying a palm; another player felling a palm.

So many players are used to this perspective. For this

reason, we decided to use this perspective in Escape

From Wilson Island.

As a narrative background, we chose a well known

scenario (’Robinson Crusoe’) which creates a setting

that motivates the players to collaborate: The play-

ers stranded on a deserted island and have to escape

from there. Therefore, they have to reach a neigh-

bored island with a high mountain to ignite a signal

fire there. The starting island contains resources like

trees for wood, bushes with berries for food, or NPC

herons running around randomly. Furthermore, the is-

land is designed in a way such that it seems realistic,

e.g. sand strands with palms near the water, hills and

other trees inland. The island has both green mead-

ows and rocky spots which look rather dangerous. In

order to reach the other island they first have to build

a raft for which they need wood and other items. Be-

fore they can start to build the raft, they have to en-

sure that they can survive on the island. Hence, they

have to build a hut to sleep and gather berries or hunt

herons for food.

The narrative background is told to the players in

a short intro showing how the players strand on the

island. At their starting point, they are welcomed by

a Non-Player Character (NPC) which tells them their

goal (leave the island) and gives hints on how to reach

it (build a hut, gather wood for a fire, gather berries

and hunt herons to have food, finally build a raft and

reach the neighboring island).

To provide an ingame help system for the players,

the NPC can be found at every time on the island and

players can ask a set of predefined questions in form

of dialogues. The NPC is also integrated in the game

in form of a person who gives quests to the players

(as additional tasks to be solved) when the game de-

velops.

The game can be played in three camera views:

1st person, 3rd person (camera following the player)

and isometric (top down). We decided to add different

camera views as different players have different pref-

erences and in various situations it can be helpful to

change the camera view. The game controls are stan-

dard ’W-A-S-D’ for movement with mouse cursor for

the direction. Camera views can be switched by use

of hotkeys. Interaction with game items is done by

mouse click (mouse curser changes whenever an ac-

tion with an item is possible when the mouse is moved

DESIGNINGCOLLABORATIVEMULTIPLAYERSERIOUSGAMESFORCOLLABORATIVELEARNING-Escape

fromWilsonIsland-AMultiplayer3DSeriousGameforCollaborativeLearninginTeams

205

over the respective item).

In the following list, we show how we applied our

design guidelines:

• Common Goal/Success: Players can only escape

together, not one player alone. An outro will be

played at the end of the game as a reward if the

games was finished successfully.

• Heterogeneous Resources: Each player has one

unique tool (axe, map, whistle, hunter’s badge)

enabling him/her to perform unique tasks in the

game which other players cannot perform, e.g.

only the player with the axe can fell palms in or-

der to get wood for building the hut, the raft or for

fire.

• Refillable Personal Resources: Need for food,

health, and fitness; The players’ avatars need to

eat from time to time in order not to starve. Fur-

thermore, they have a fitness value which regen-

erates when the avatars are sleeping. The fitness

value is influenced by running and working. A

lack of fitness slows players down. The health

value is negatively influenced when players are

starving or when they are drowning. It is regen-

erated when eating or sleeping.

• Collectable and Tradable Resources: Wood,

Berries, Meat; There are two ways to get food:

A player can gather berries from a bush which re-

store a small amount of saturation, or the play-

ers can hunt a heron, which will give them some

pieces of meat that can be cooked. Each piece

of cooked meat restores a large amount of satura-

tion, making heron meat a lot more valuable than

berries. Wood can be gathered from palms if they

are chopped.

• Collaborative Tasks: Some tasks are only solv-

able if players act together: Felled palms can only

be carried in team (dependent of the size, this re-

quires 2-3 players). Herons can only be hunted in

team, as they have to be surrounded, which needs

at least 2 players but is easier if more players take

part in it. The raft can only be steered when all

players are participating, as each player can only

sit in one corner, steering the raft towards his/her

corner when paddling. So the players have to co-

ordinate their actions when steering the raft.

• Communication: Players are able to communi-

cate with each other via an integrated chat. We

integrated a simple chat window for the players

where a player can select the listeners. It is possi-

ble to chat with only one other player, with a set

of other players or with all other players. The chat

window is always visible in the lower left corner.

Of course, it is also possible to allow players in

the same room to talk with each other or to use

a third party tool for communication like Skype,

TeamSpeak or Mumble.

• Ingame Help System: We integrated an NPC,

which is living on the island. The NPC’s task is to

guide the players through the game, giving them

hints when necessary and answering some game

related questions. The NPC communicates with

the players via a predefined structured chat sys-

tem or can be controlled by another player, e.g. a

teacher. It then is able to talk to the players via

a chat system or the teacher can design structured

dialogs ad-hoc at runtime.

• Scoreboard: At the end of the game, each player

will have an individual score that is visible to the

whole group. The score depends on the number

of (potentially) helpful actions performed during

the game like gathering berries, carrying wood,

building the raft, helping to catch a heron, etc.

• Trading System: Every player has a personal

inventory where he/she can place items gathered

throughout the game. Those items can be given to

other players by placing them in a community box

accessible by every player. Access to the chest is

trust based, there is no control mechanism to pre-

vent someone from taking something out of the

chest.

To make the ingame feeling more realistic and to

increase immersion we included some sound effects

(footsteps, sounds for opening boxes, etc.). Addition-

ally, the NPC dialogs are spoken by a real human

voice simultaneously to the text. In Figure 2, play-

ers are shown during a collaborative action (carrying

a palm) while another player is felling another palm.

5 RESULTS

5.1 Setup

For evaluation of EFWI, we made a user centered

study with 23 participants and the following setup:

After a five minute introduction into how to play

the game (goal, controls, etc.), games were played

in groups of four players per game (one group with

only three players). All players were located in one

room, observed by two members of our team. Each

gaming session took 30 minutes after which the par-

ticipants had to stop playing and answer a question-

naire. The questionnaire retrieved information about

User Experience (UX) and game design. Further-

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

206

Table 1: User experience questions.

Min Max Mean Dev

No Boredom 3 10 8.70 1.74

No Frustration 1 10 5.87 2.07

No Anger 1 10 7.00 2.39

Challenged 2 10 7.35 2.12

Fantasy 1 10 5.91 2.83

No Overload 3 10 6.96 2.01

Fun 5 10 9.00 1.28

Competence 2 9 6.39 1.83

Esthetics 3 10 6.09 2.00

Immersion 4 10 7.87 1.91

Motivation through

development 4 10 8.13 1.74

Self-Rewarding 1 10 5.30 3.07

Part of game world 2 10 6.30 2.27

Identific. with char. 1 10 5.87 2.82

Development of

own concept 1 10 6.39 1.97

Attention claiming 3 10 7.87 1.69

Loss of time 5 10 8.91 1.20

Compelling and

engaging 2 10 7.26 2.09

Relief due to failure 1 9 4.43 2.57

Emotionally involved 1 10 7.09 2.18

Comfortable State 4 10 7.39 1.95

more, the participants were asked to freely add com-

ments about what they liked, disliked or missed. In

addition, we logged game relevant information about

player performance, success, and player behavior. We

set up goals for all teams requiring collaboration to be

reached: survive, build a hut, hunt a heron, and build

a raft. In order to build the hut, one player had to fell

palms, and three players had to carry the palm to the

destination (which is difficult as players have to coor-

dinate their movements in order not to drop the palm).

To capture the heron, at least three players had to sur-

round it while pushing it towards a cliff. One player

(the one with the hunters badge) can see possible es-

cape routes of the heron which players have to close

by moving cleverly before the heron runs away. This

requires a significant amount of coordination. Also,

before the players can surround the heron, the player

having the whistle has to attract it. The whole process

is only possible if the team works collaboratively.

5.2 Questionnaire

To test for User Experience, a questionnaire was used

after playing the game for 30 minutes. Not only posi-

tive and negative emotions were asked about, but dif-

ferent concepts like immersion and flow were used,

Table 2: Game design questions.

Min Max Mean Dev

Free choice of tasks 1 10 6.36 2.74

Many interesting tasks 3 10 7.26 1.71

Clear goal 3 10 7.91 2.29

Rich impressions 1 9 5.70 1.66

No Boredom 1 10 5.83 2.69

Freedom of action 1 10 6.22 2.45

Control of avatar 2 10 6.57 2.00

Sustainable changes 3 10 6.61 1.64

Feedback of success 5 10 7.83 1,53

Hints for task solution 1 10 6.91 2.09

Fate of character 1 10 5.26 2.42

Interesting places 1 8 4.65 2.27

Development of

Own identity 1 8 4.22 1.86

Own style of play 1 9 5.65 2.42

Emotionally

supporting music 1 5 1.78 1.28

Available options

always clear 2 9 6.13 1.79

Conditions clear 3 10 6.83 1.90

State of game visible 1 10 6.35 2.40

Part of solved tasks 1 10 6.83 1.77

Difficulty related

rewards 1 10 5.22 2.39

How close to goal 1 9 5.78 2.09

Acknowl. and status 1 8 4.22 2.11

Possibility of

further develop. 1 8 5.35 1.92

Knowledge acquired 1 9 6.35 1.92

Interesting characters 3 10 4.35 1.53

Good story 1 10 6.30 2.20

Interesting form

of narration 1 9 5.00 2.71

Tasks vary in difficulty 1 10 5.52 2.73

Training of skills 1 9 6.26 2.09

Interest. side narrations 1 9 5.04 2.40

too. Following (Nacke, 2009) (p. 146), we define im-

mersion as

”immersion in the game world derives from

the player becoming the game character, in the

sense of the player having the experience of

acting within the game world”

and as (Przybylski et al., 2009) suggest, perceived au-

tonomy and competence may be an important source

of positive emotions. Believing that there could be a

link between the game design and the UX, we split

the questionnaire in items testing elements of game

design (like ”ability to choose between different tasks

on his/her own”) and items testing elements of UX

DESIGNINGCOLLABORATIVEMULTIPLAYERSERIOUSGAMESFORCOLLABORATIVELEARNING-Escape

fromWilsonIsland-AMultiplayer3DSeriousGameforCollaborativeLearninginTeams

207

(like positive and negative emotions) to have a closer

look on the possible link between UX and game de-

sign. Seven dimensions of UX and ten dimensions of

game design were asked in the questionnaire. Every

dimension includes three items, which could be an-

swered on a ten point scale (10 = ”I agree”, 1 = ”I

don’t agree”). The mean of the 21 items (see Table 1)

of the seven UX scales can be interpreted as a value

of the UX. The 30 items (see Table 2) of the 10 game

design scales can show specific weaknesses of the vir-

tual world.

5.3 Critics and Suggestions

In addition to the questionnaire, we asked the par-

ticipants to give feedback in form of critics or sug-

gestions for improvement. The most frequently men-

tioned problems were:

• Improvement of character control (12 / 23).

• Need for a minimap (5 / 23).

• More camera views (5 / 23).

• Improvement of graphics (4 / 23).

• More interaction with game world /

more tasks (4 / 23).

• More ways to differentiate the own avatar from

others (4 / 23).

5.4 Game Relevant Logged Data

In order to measure what and how much the player

groups achieved during the 30 minutes of play, we

logged several actions: berries gathered, berries ate,

palms felled, palms carried, fires ignited, wood added

to fire, meat chopped, meat roasted, dialogues with

NPC, herons caught. These data was logged for each

player and for the group. Additionally, we logged the

player chat, so that we could see, which player chat-

ted with which other player(s), and how often. The

logged data was saved to log files after the gaming

sessions ended.

5.5 Discussion

As shown in Table 1, the participants perceived the

game as fun, engaging and motivating through its de-

velopment. They also were in an convenient condi-

tion, felt a loss of time and paid a lot of attention to

the game. These are indications for a high perception

of immersion. The most negative value was ’Relief

due to failure’, which we interpret like follows: Usu-

ally this emotion occurs when a player is in a state

of high tension (like in a shooter, or a horror game).

Many players feel better immediately after being shot

in a shooter because the tension is gone. In EFWI, we

have no ’life threatening’ circumstances, so there is

hardly any failure which could reduce a form of ten-

sion, which then could cause a form of relief to the

player. Also players did not really identify with their

avatars and found the game a little frustrating from

time to time which we can credit mainly to the diffi-

cult controls (see later in detail) and some bugs.

Table 2 shows mostly average or slightly positive

values. However, there is a number of very low val-

ues, which we want to discuss here. ’Own identity’

has an average value of 4.22, which means players do

rather not think that they can create an own identity

with their character. In fact, there is currently no op-

tion to personalize the avatar in an optical way (skins,

pieces of cloth, etc.) or by development of virtual

character skills as usual in role playing games. Also,

the bad value for ’Interesting characters’ may be ex-

plained by this fact. Music is rated very low which

is not surprising as there is currently no music in the

game. The players seem to evaluate this very neg-

atively which indicates a demand for a background

music. However, it is interesting that some players

did obviously not miss music as crossed a value of 5,

which is rather neutral. ’Acknowledgment and sta-

tus’ is rated with 4.22 on average, which means that

players did rather not feel they received the proper

acknowledgment for their effort in the game. This

may be due to the fact that the scoreboard is only dis-

played after the game. Also currently, there are no

achievements implemented which could display a cer-

tain progress to the player.

So, we can assume that all of our player groups

had fun at playing, many of them wanted to play on

for ’just a few more minutes’ after the 30 minutes of

play. The good values in the UX part with a mean

value of 6.95 and a standard deviation of 1.10 support

this hypothesis. The Cronbach’s alpha of the UX part

of the questionnaire is .82 which indicates that the UX

question set belongs to one construct. However, the

players criticized some gaming parts like controlling

the character or graphics. These are implementation

details which we will have to address. The need for

a minimap for a better orientation is a real deficiency

which we will have to solve. Also more interactions

with the game world should be necessary in order to

keep the game interesting for a longer time. Addi-

tionally, we will have to include more sounds and a

meaningful background music.

Although we did not measure success by num-

bers or recorded the discussions between the play-

ers, we can state some interesting observations: All

teams were able to achieve at least some if not all of

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

208

the goals given by us in 30 minutes for which they

had to collaborate. This indicates that it is possible

to design collaborative tasks in a computer game for

training of collaboration. We could observe the play-

ers to talk to each other about problems to be solved

in the game, thus discussing their working relation-

ships, helping and promoting each other’s success.

Although we did not measure any improvement of so-

cial skills like teamwork, coordination, or communi-

cation, we can say that all of those skills have been

used by the players throughout the game. This indi-

cates that it is possible to specifically improve those

skills using a proper game design.

During the gaming sessions, we noticed two dif-

ferent types of groups. Some groups had a clearly

visible team leader while others did not have. Teams

with a team leader seemed to perform better than

teams without. Those teams seemed not to collabo-

rate at all. We noticed that those teams mostly ful-

filled solo tasks like gathering berries or felling trees,

but it took them very long to carry a palm to the place

where the hut was to be build or to hunt a heron. Some

teams did not achieve to hunt a heron at all. We in-

tend to further investigate this in a follow-up evalu-

ation centered on team behavior and team leader be-

havior.

Regarding our design guidelines, we observed that

the common goal was clear to the players. The het-

erogeneous resources made players coordinate their

actions and the refillable personal resources (e.g.

hunger value) made players help each others. We ob-

served players gather food (berries) for other players,

so that those could concentrate on other tasks. There-

fore players used the collectable and tradeable re-

sources (like berries or wood for fire). Furthermore,

we could observe players to solve the collaborative

tasks, which could only be solved in a group (i.e.

carrying a palm). All teams significantly improved

at performing this task throughout the game which

indicates that they improved their coordination (for

this task) during play. As all players were seated in

one room, they were able to communicate verbally

with each other. The ingame help system in form

of an NPC was used very intensely by some groups,

whereas other groups failed to use it. This indicates

that another help option like an always present help

button may be useful, too. Due to the time restrictions

of the evaluation, the game could not be played to the

end, so that no scoreboard could be shown to players.

The trading system was used by players, but without

an individual goal, there was no motivation not to col-

laborate, so no real trading could be observed.

Our results indicate that it is possible to design

and create multiplayer Serious Games which meet

the requirements of collaborative learning principles

by using principles of collaborative gameplay and to

practice collaborative learning in a game-based learn-

ing environment combining the advantages of game-

based learning with those of collaborative learning.

We think that it is easily possible to extend the

game(play) of EFWI in a way such that players learn

something in the game beyond teamplay and social

skills.

6 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper we proposed an approach for collab-

orative gameplay in 3D multiplayer Serious Games

as a foundation for game-based collaborative learn-

ing. Resulting from an extensive literature review, in

our approach we tried to combine game design guide-

lines for collaborative games with the requirements

of cooperative learning. Our resulting approach was a

game design for a 3D multiplayer game for 3-4 play-

ers with a collaborative gameplay as a foundation for

collaborative learning. We implemented a prototype

using our game design approach with a 3D game en-

gine and performed a user centered study for evalua-

tion of user experience and game design issues. Re-

sults of the evaluation are promising. Players had a

lot of fun playing the game despite some miner draw-

backs like poor graphics or difficult controls. We

could observe the players to be able to solve tasks for

which they had to collaborate. We also could observe

players making use of social skills like communica-

tion skills, teamwork, etc. while playing. Further-

more, we recognized an influence caused by the pres-

ence or absence of a team leader. This indicates that

collaborative multiplayer games supporting collabo-

rative learning can be promising alternative to tradi-

tional CSCL.

Next steps will include the implementation of the

demanded missing features. Furthermore, we will

extend gameplay with more tasks. Also, it will be

necessary to include subject specific tasks to be able

to evaluate the learning outcomes of the game (e.g.

in form of a pre-post-test). One major feature will

be the inclusion of a Game Master component for a

teacher/trainer to be able to oversee, control and adapt

the game according to his/her professional opinion at

runtime. The Game Master can either play a leading

role or be a passive and invisible control instance. In a

follow-up study we want to evaluate which effects on

collaboration the presence of such a Game Master can

have and if it can improve the learning performance of

players in a collaborative multiplayer Serious Game.

DESIGNINGCOLLABORATIVEMULTIPLAYERSERIOUSGAMESFORCOLLABORATIVELEARNING-Escape

fromWilsonIsland-AMultiplayer3DSeriousGameforCollaborativeLearninginTeams

209

REFERENCES

Baker, M. and Lund, K. (1997). Promoting Reflective

Interactions in a Computer-supported Collaborative

Learning Environment. Journal of Computer Assisted

Learning, 13:175–193.

Crawford, C. (1984). The Art of Computer Game Design.

Osborne/McGraw-Hill.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The Psychology of Op-

timal Experience. Harper Perennial.

Delwiche, A. (2006). Massively Multiplayer Online Games

(MMOs) in the New Media Classroom. Educational

Technology & Society, 9(3):160–172.

Dillenbourg, P. (1999). What Do You Mean by Col-

laborative Learning? In Dillenbourg, P., edi-

tor, Collaborative-learning: Cognitive and Computa-

tional Approaches, pages 1–19. Elsevier, Oxford.

Gee, J. P. (2003). What Video Games Have to Teach Us

About Learning and Literacy. Computers in Enter-

tainment (CIE), 1:20.

H

¨

am

¨

al

¨

ainen, R., Manninen, T., J

¨

arvel

¨

a, S., and H

¨

akkinen, P.

(2006). Learning to Collaborate: Designing Collabo-

ration in a 3-D Game Environment. The Internet and

Higher Education, 9(1):47 – 61.

Harteveld, C. (2011). Triadic Game Design. Springer-

Verlag New York Inc.

Johnson, D. and Johnson, R. (1994). Learning Together and

Alone, Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic

Learning. Needham Heights, MA: Prentice-Hall.

Kelly, H., Howell, K., Glinert, E., Holding, L., Swain, C.,

Burrowbridge, A., and Roper, M. (2007). How to

Build Serious Games. Communications of the ACM,

50(7):44–49.

Kiili, K. (2005). Digital Game-based Learning: Towards an

Experiential Gaming Model. The Internet and higher

education, 8(1):13–24.

Larusson, J. and Alterman, R. (2009). Wikis to Support the

Collaborative Part of Collaborative Learning. Interna-

tional Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative

Learning, 4(4):371–402.

Manninen, T. and Korva, T. (2005). Designing Puzzles for

Collaborative Gaming Experience–CASE: eScape. In

Castell, S. and Jennifer, J., editors, Selected papers

of the Digital Interactive Games Research Associa-

tions second internationalconference (DiGRA 205),

pages 233–247, Vancouver, Canada. Digital Interac-

tive Games Research Association.

Nacke, L. (2009). Affective Ludology: Scientific Measure-

ment of User Experience in Interactive Entertainment.

PhD thesis, Blekinge Institute of Technology, Karl-

skrona, Sweden. http://phd.acagamic.com, (ISBN)

978-91-7295-169-3.

Nelson, B. and Ketelhut, D. (2008). Exploring Embed-

ded Guidance and Self-efficacy in Educational Multi-

user Virtual Environments. International Journal of

Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 3:413–

427. 10.1007/s11412-008-9049-1.

Onrubia, J. and Engel, A. (2009). Strategies for Collab-

orative Writing and Phases of Knowledge Construc-

tion in CSCL Environments. Computers & Education,

53(4):1256 – 1265.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Game-based Learning. Mc-

Graw Hill.

Przybylski, A., Ryan, R., and Rigby, C. (2009). The Moti-

vating Role of Violence in Video Games. Personality

and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35:243–259.

Rauterberg, G. (2002). Determinantes for Collaboration in

Networked Multi-user Games. In Entertainment Com-

puting: Technologies and Applications.

Roschelle, J. and Teasley, S. (1995). The Construction

of Shared Knowledge in Collaborative Problem Solv-

ing. In OMalley, C., editor, Computer-supported Col-

laborative Learning, pages 69–97, Berlin. Springer-

Verlag.

Said, N. (2004). An Engaging Multimedia Design Model.

In Proceedings of the 2004 conference on Interaction

design and children: building a community, pages

169–172. ACM.

Salen, K. and Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of play: Game

Design Fundamentals. The MIT Press.

Squire, K. (2003). Video Games in Education. Interna-

tional journal of intelligent simulations and gaming,

2(1):49–62.

Stahl, G., Koschmann, T., and Suthers, D. (2006). Cam-

bridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences, chapter

Computer-supported Collaborative Learning: An His-

torical Perspective, pages 409–426. Cambridge Uni-

versity Press.

Voulgari, I. and Komis, V. (2008). Massively Multi-user

Online Games: The Emergence of Effective Collabo-

rative Activities for Learning. In DIGITEL ’08: Pro-

ceedings of the 2008 Second IEEE International Con-

ference on Digital Game and Intelligent Toy Enhanced

Learning, pages 132–134. IEEE Computer Society.

Wendel, V., Babarinow, M., H

¨

orl, T., Kolmogorov, S.,

G

¨

obel, S., and Steinmetz, R. (2010). Transactions

on Edutainment IV, volume 6250 of Lecture Notes

in Computer Science, chapter Woodment: Web-Based

Collaborative Multiplayer Serious Game, pages 68–

78. Springer, 1st edition.

Wendel, V., G

¨

obel, S., and Steinmetz, R. (2011). Seamless

Learning In Serious Games - How to Improve Seam-

less Learning-Content Integration in Serious Games.

In Proceedings of the CSEDU 2011, volume 1, pages

219–224. SciTePress - Science and Technology Pub-

lications.

Zagal, J. P., Rick, J., and Hsi, I. (2006). Collaborative

Games: Lessons Learned From Board Games. Sim-

ulation and Gaming, 37(1):24–40.

Zea, N. P., S

´

anchez, J. L. G., Guti

´

errez, F. L., Cabrera,

M. J., and Paderewski, P. (2009). Design of Educa-

tional Multiplayer Videogames: A Vision From Col-

laborative Learning. Advances in Engineering Soft-

ware, 40(12):1251–1260.

Zyda, M. (2007). Creating a Science of Games. Communi-

cations of the ACM, 50(7):26.

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

210