EXPERIMENTING WITH ENGLISH COLLABORATIVE

WRITING ON GOOGLE SITES

Nicole Tavares and Samuel Chu

Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong,

Centre for Information Technology in Education, Pokfulam, Hong Kong

Keywords: Collaborative Learning, English Writing, Primary Schools, Google Sites, Wikis, Hong Kong.

Abstract: A considerable amount of research in recent years has shown the advantages of integrating Web 2.0

technologies with language teaching. Specifically, this paper will shed light on the positive effects of

web-based collaborative writing on Google Sites based on a project carried out in four primary schools in

Hong Kong, as revealed by the qualitative data samples of students’ and teachers’ comments and revisions,

as well as the result of focus group interviews. Both students’ and teachers’ revisions and feedback not only

endorse but also expand on the benefits of using Google Sites in the linguistic, discourse and motivational

domains for students as suggested by previous research findings. Key observations based on the present

study will also be highlighted to offer insights into ways of merging Web 2.0 technologies and language

teaching in a second or foreign language context like that of Hong Kong.

1 INTRODUCTION

Writing has always been a challenge to students

learning a second or foreign language, not to

mention young learners in a primary school context.

While acknowledging the fruitful results of using

web-based collaborative tools in promoting writing

in group projects across different subjects (Woo et

al., 2011), this study aims to examine the extent to

which collaborative learning in a Web 2.0

environment can enhance students’ writing abilities

in English. Web 2.0 technologies have been

increasingly perceived by teachers, parents and the

general public as an essential tool for equipping

students with the necessary skills, such as

communication and collaboration skills, required in

the 21

st

century (Zammit, 2010). Google Sites is also

believed to provide students with a free online

collaborative platform to co-construct their group

projects — an avenue that enables teachers to

engineer discussions that activate students to see

each other as resources and owners of their own

learning, to monitor their learning progress and to

provide timely feedback that moves them forward

(Wiliam, 2005).

This paper will highlight the literature guiding

the design of the study, discuss the intervention

program prior to and during the project, outline the

data collection methods, report on the main findings,

and raise issues for critical reflection.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

New technologies have been found to have a

tremendous impact on the teaching and learning of

English writing in the last few decades (Goldberg et

al., 2003). Many studies have started to bring in the

application of Web 2.0 in education involving

collaborative tools called wikis (Woo et al., 2011).

Hossain and Aydin (2011) have suggested that social

networking applications such as blogs, forums,

podcasts and wikis are successful in creating a

collaborative virtual society for users to share

information interactively. Google Sites, a kind of

wiki, is a “collaborative web space where anyone

can add content and anyone can edit content that has

already been published” (Richardson, 2006, p. 8).

A considerable number of studies in the past

decade has pointed out specific benefits of Google

Sites and other similar wikis. First of all, such form

of technology can promote social and achievement

motivation. The interactive and read-write nature of

Web 2.0 technologies facilitates users’ participation

in and building of many rich and user-centered

virtual communities (Alexander, 2006). What’s

more, providing a genuine audience to the

217

Tavares N. and Chu S..

EXPERIMENTING WITH ENGLISH COLLABORATIVE WRITING ON GOOGLE SITES.

DOI: 10.5220/0003924502170222

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2012), pages 217-222

ISBN: 978-989-8565-06-8

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

participants motivates them become more engaged

writers (Lo & Hyland, 2007). With this, they are

likely to get more actively involved in the co-writing

process (Parker & Chao, 2007) and in their own

knowledge construction (Boulos et al., 2006).

Apart from igniting students’ motivation to be

involved in the writing process, Google Sites also

offers a convenient context for them to contribute in

various ways. Hossain and Aydin (2011) indicated

that wikis allow users to have different levels of

access to edit or delete content. Students can play a

part according to their availability as well as their

ability. This study provides solid evidence of this in

Section 4 of the paper.

Most recently, Woo et al. (2009) conducted a

study to explore the challenges and benefits that a

wiki may bring to the students and teachers in a

primary five English class in Hong Kong. The

results showed that the students held a positive

attitude towards both the process and the product of

the collaborative writing experience. A follow-up

investigation done by Woo et al. (2011) on students

of the same age group has reconfirmed previous

findings that students enjoy using the wiki and that it

had a significant impact on their collaboration and

writing skills development. Although these two

studies and a few others (e.g., Wheeler et al., 2008)

have generated encouraging results in the use of

wikis to facilitate primary students’ writing and

revision of their texts, no larger scale projects have

been carried out in Hong Kong with students of

different ability groups in primary schools across the

territory to investigate the value of using Web 2.0

technologies in English language learning. This

paper therefore aims to bridge these research gaps

by describing the effects of using Google Sites for

collaborative English writing online with examples

of students’ work from four local primary schools.

The divergence in the approach adopted by the

teachers in the four schools in monitoring their

students online is nevertheless beyond the scope of

this discussion here.

3 RESEARCH METHOD

3.1 Participants

Four primary schools located in different parts of

Hong Kong, including KF, SH, CP and WS

1

, were

1

KF = CCC Kei Faat Primary School; SH = Cheung Chau Sacred Heart

School; CP = Canossa Primary School; WS = STFA Wu Siu Kui Memorial

Primary School (a.m.). The population in these four schools should reflect

the language performance of upper primary students in the higher, average

and lower range across the territory.

invited to participate in this project so as to ensure

that a sufficient quantity of student writings

representative of those of the average local primary

student population could be gathered to examine the

effects of online collaborative writing in English.

The 401 Primary five students who took part in the

study were first required to do at least one

collaborative piece of writing on paper in the first

term (Phase One) to experience writing as a team

and to be acquainted with peer evaluation, a part of

the intervention program to be discussed in 3.2. In

the second term (Phase Two of the study), students

completed their writing on Google Sites. The four

schools differed in terms of the number of classes

involved, the composition topic as well as the

duration and details of their implementation plan. At

KF, for example, two classes took part in the study

and their writing topic was Our Weekend Activities.

Similarly, two classes from SH joined the study with

Cheung Chau Bun Festival as their theme. CP had

Lost as their topic while WS chose Good Person,

Good Deeds; both CP and WS had a larger number

of students taking part in the study. It is worth noting

that all the topics were closely relevant to the

students’ daily life, school activities and lesson

focus.

3.2 Intervention Program

Teachers facilitated students’ writing in a

pen-and-paper format in the first phase and then via

Google Sites in Phase Two. Pre- and

while-intervention professional development

workshops were held and teachers from the four

participating schools took part. Two pre-intervention

workshops were organized prior to the

commencement of the study and designed to deepen

the teachers’ understanding of the potential benefits

of process and collaborative writing using White and

Ardnt’s (1991) model that illustrates the cyclical and

developmental nature of the writing process as

shown below. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: (White & Ardnt, 1991, p. 4).

At the workshops, the teachers’ knowledge of the

writing process, approaches to the teaching of

writing, their role in facilitating learning and the

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

218

giving of quality feedback was strengthened. In

particular, the teachers were reminded of the

importance of having a clear set of assessment

criteria and ways of guiding their students in

interpreting the criteria and evaluating one another’s

written work with the help of different evaluation

templates. The workshop organized during the

intervention provided the opportunity for the

teachers from the four schools to come together

again to share and reflect on their experience of their

try-outs in Phase One, to compare the evaluation

templates they used and the impact on the quality of

students’ written work, to voice their concerns and to

collectively plan ahead for Phase Two. What was

notable about this while-intervention workshop was

that teachers received feedback on the comments

they made on their students’ work, discussed the

impact of their use of prompts, questions,

suggestions and revisions in different forms, and

explored how they could maximize the benefits of

their strategy use.

3.3 Data Collection

3.3.1 Focus Group Interviews with Teachers

and Students

Focus group interviews were conducted on 42

students and 19 teachers from the four participating

schools to gather their opinions on the use of Google

Sites. In general, the majority held a positive attitude

towards Google Sites as a collaborative writing

platform. Some interesting qualitative findings are

captured in Section 4 of the paper.

3.3.2 Documentary Analysis of the Students'

Progress

Google Sites has the function of ‘page history’ that

generates information on the person making the

revisions and identifies the types of revisions done,

thereby enabling one to trace how different kinds of

peer and teacher feedback lead to the latest version

of students’ work. Qualitative data was thus

gathered and analyzed through multiple sources of

evidence, including students’ first drafts, peer

evaluation of their writing from their group mates

and classmates depending on the accessibility of

their writing to everyone in class as determined by

the teachers, information edited as recorded in the

wiki history page and a comparison of this with the

revised texts posted on Google Sites. The analysis

revealed benefits for students of different ability

groups and this is documented below.

4 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

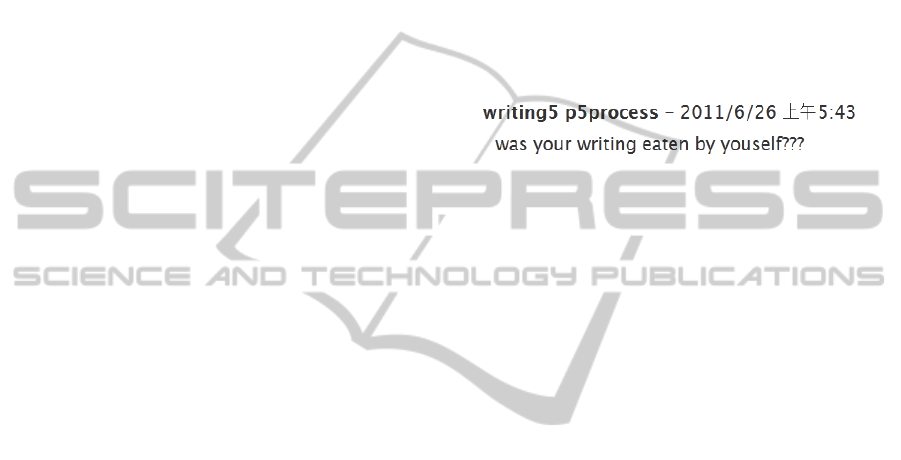

4.1 Positive Pressure to Write

Throughout Phase Two of the study, when writing

was all done on Google Sites, it was observed that

there were fewer instances of non-starters, compared

to writing in the pen-and-paper format. As

exemplified in the online exchanges below from a

class of students in CP, the candid and innocent

responses from students such as “was your writing

eaten by yourself ?” served as a powerful socially

motivating factor in encouraging their friends to at

least begin to write:

Figure 2: Sample one.

Another comment “You are very lazy” by a

classmate was also proven to be more persuasive

than a similar remark made by the teacher as it came

in a more timely fashion on Google Sites than it

would on paper and was made public to everyone in

the class.

4.2 Writing for a Real Audience

Students generally valued Google Sites as an avenue

for mutual exchange, peer learning and publication

of their work. Comparing this to the pen-and-paper

mode they experienced in an earlier phase of the

study, two students had the following views: “When

we use Google Sites, we have the chance to read the

compositions from other classes, comment on our

classmates’ work and exchange ideas. When we did

our work on paper, we could only read a few pieces

of writing.” “Google Sites allows other people to

comment on our work and we can learn more from

that.” Interestingly, a third student shared the pride

he took in having the opportunity to publish his

work: “… we can save our work easily on Google

Sites and show it to others.”

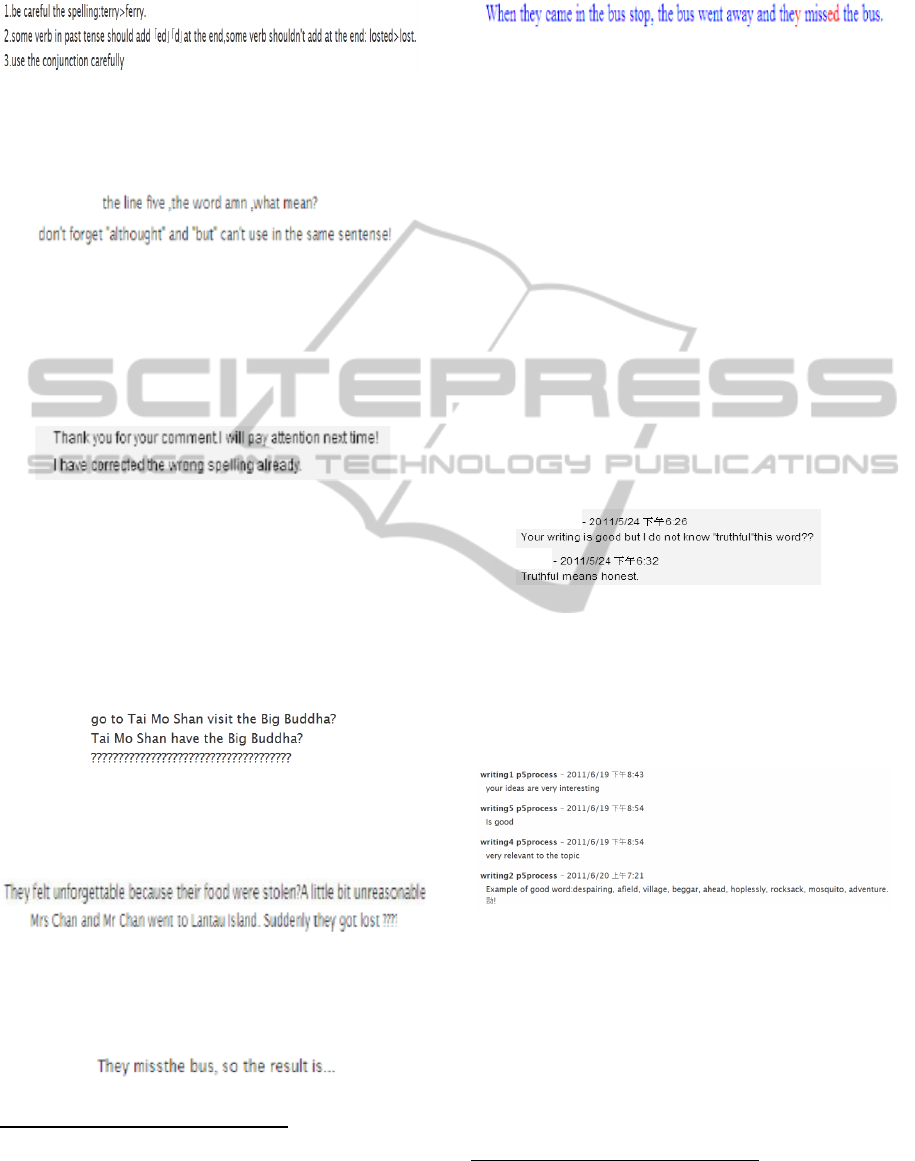

4.3 Better Writing and Peer Learning

It is precisely because of the communicative nature

of this collaborative writing platform that students

have demonstrated their interest in commenting on

not only the orthographic, grammatical and syntactic

aspects of their peers’ writing but also, much more

importantly, its content.

While some linguistically more advanced

students were seen making detailed suggestions for

EXPERIMENTINGWITHENGLISHCOLLABORATIVEWRITINGONGOOGLESITES

219

their peers on spelling, tenses and the use of

conjunctions as indicated below,

Figure 3: Sample two.

their not-so-strong counterparts

2

left comments such

as

Figure 4: Sample three.

which had an equally positive influence on their

peers’ revisions as shown in their edited work. The

communicativeness of such exchanges is further

evidenced through responses to the comments above

and actions taken by students:

Figure 5: Sample four.

Even more impressive were nevertheless the

questions that students raised which led their

classmates to reflect on and revise their writing on

the content level. For example, one student noticed a

classmate writing a story about The Big Buddha in

Tai Mo Shan and posed the following two questions

for him

3

:

Figure 6: Sample five.

Other examples of comments of this nature

include:

Figure 7: Sample six.

These friendly but stimulating and provoking

questions, plus helpful prompts such as

Figure 8: Sample seven.

2

The students were classified as high, average and low performers in the

English language by their teachers according to their official results in

school.

3

Geographically, The Big Buddha is situated on Lantau Island in Hong

Kong and not Tai Mo Shan.

in response to a writer who brought his composition

to a close with the following sentence

Figure 9: Sample eight.

gave their fellow students useful pointers to revise

their work by further developing their ideas,

enriching the content of their writing and fixing

problems with relevance for overall greater logical

and textual coherence

4

. This not only supports the

argument put forward by Woo et al. (2009) that

primary students have the ability to comment on

their peers’ work but even takes it further to prove

that they are capable of reviewing one another’s

writing in different dimensions, given appropriate

guidance from the teacher.

There were also concrete examples of peer

learning and peer tutoring at work from the average

to lower performers as identified by their teachers.

In the following instance, a student was noted

reading another group’s piece of writing and, in his

eagerness to understand its content, tried to find out

what “truthful” means and got this reply:

Figure 10: Sample nine.

Overall, both teachers and students were found

giving encouraging feedback on ideas as well as

language use as shown in some of the examples

cited above and in this interaction between four

students and the target writer:

Figure 11: Sample ten.

All this is reinforced by the students’ perceptions

as expressed in focus group interviews that “Google

Sites allows other people to comment on (their)

work and (so they) can learn more from that” and

teachers’ beliefs that this collaborative environment

offers the advantage of “promot(ing) the writing

skills of a group of students – not just one”. What is

4

There were ample examples of this from the ‘page history’ and improved

versions of students’ work based on their classmates’ feedback which

unfortunately the limited space in this paper does not allow us to show.

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

220

worth highlighting too is that the students were in

general writing more than they would otherwise

have produced in a pen-and-paper format, and were

communicating most of the time in the target

language – English – in natural, spontaneous and

anxiety-free ways.

4.4 Teachers’ Role in the Collaborative

Writing Process

Teachers’ roles can be conceptualized as being

three-fold in the process of guiding their students in

completing the collaborative writing task: (i) as “a

genuine and interested reader” (White & Ardnt,

1991, p. 125) who responded naturally to the content

of students’ writing as Ms Cheng from KF below

attempts to achieve.

Figure 12: Sample eleven.

(ii) as facilitator in helping students strengthen the

quality of their ideas as Ms Cheng does above with

her suggestion “You can describe the appearance of

(your) mum, how hard-working she is, how good

she is” or as another teacher Ms Kwok from KF

does through the use of questions:

Figure 13: Sample twelve.

and (iii) as language assistant (Tribble, 1996, p. 119)

as a teacher from WS Ms Lam illustrates via her

prompts and guidance given to a student on his

grammatical mistakes:

Figure 14: Sample thirteen.

4.5 Benefits of Google Sites in Itself

Overall students found the experience of writing on

Google Sites rewarding. Endorsing a teacher’s view

that “(a)ll students have the right to evaluate other

groups’ work and later the groups share their work

with the other class and comment on it” and that

students “learn to appreciate others’ work and ideas”,

here are some student voices: “If there are some

words we don’t know how to spell, we can look them

up in the dictionary immediately by using the

computer.”“Using the computer greatly arouses my

interest in writing in English.”

The word-search, spell-check and translation

options made available to students via Google Sites

have made them find “working online more

convenient” and the editing process less

cumbersome, giving them “the motivation to

accomplish tasks” not in their mother tongue.

5 TEACHING IMPLICATIONS

AND CONCLUSIONS

Indeed, “(o)ne can get close to perfection through

producing, reflecting on, discussing, and reworking

successive drafts or a text” (Nunan, 1991). There is

no doubt that self-reflection and peer evaluation

have the potential of giving students extensive

practice in developing the skills necessary for

editing and revising their work before it reaches

‘perfection’ (Witbeck, 1976). We have seen from the

online exchanges cited in this paper how students of

varying abilities took part in and benefitted from the

use of Web 2.0 technologies. Yet there is still room

to learn from the more successful implementations at

different schools based on the observations of the

researchers. It is in this light that some

recommendations for the use of such technologies

are to be made.

Throughout the study, it was observed that

schools and teachers that opened up the online

platform for students to post their work as early in

the writing process as possible created greater

opportunities for students to receive feedback from

their teachers and peers. These students were also

found making more thorough and advanced

revisions on the content, organization and language

of their writing. This suggests the need for teachers

to help students view Google Sites or similar online

writing environments as a risk-taking and supportive

avenue for them to experiment with language use

while not being afraid of showing their mistakes to

and learning from as well as with one another.

Teachers who were identified to have succeeded

in stretching their students’ potential more fully were

ones who grasped the chance to make use of student

comments such as “Too short!” or “Very long!” to

guide them in discovering how they could better

develop their ideas or learn from other students to

make their writing richer in content and more

coherent. The quality of these teachers’ feedback

was also notable.

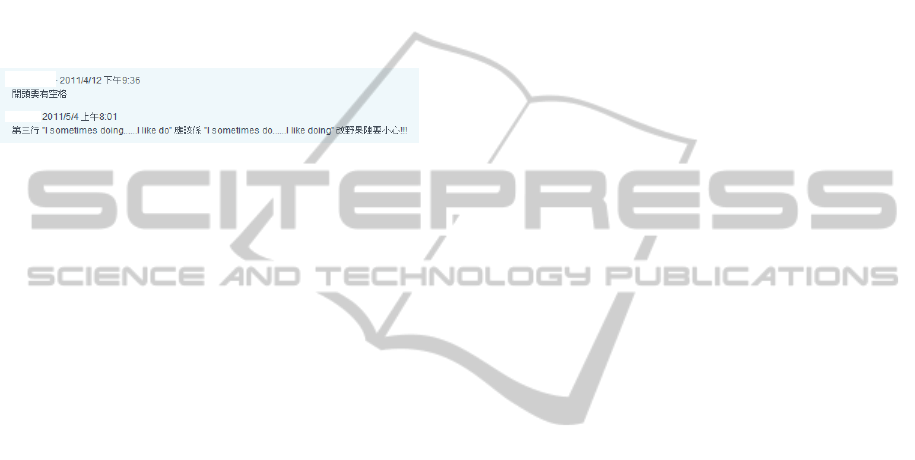

The environments found to be more conducive to

constructive and specific feedback from students

were also ones where the teachers were more

EXPERIMENTINGWITHENGLISHCOLLABORATIVEWRITINGONGOOGLESITES

221

tolerant of students’ use of their first language (L1).

What one may wish to question is whether or not

there should be an insistence on an all-English

interaction at the expense of non-communication or

whether teachers should acknowledge students’

relevant contributions in L1 and then guide them in

gradually using more of the target language. After all,

aren’t words of praise like “ 勁 !” (meaning

“Brilliant!”) as quoted in Figure 11 more reinforcing

in the students’ L1? Shouldn’t concepts which may

be difficult to express, such as the idea of indenting

the paragraph from the first suggestion below, be

encouraged?

Figure 15: Sample fourteen.

All in all, the primary students who took part in

the study generally enjoyed using Google Sites,

experienced the linguistic, discourse-related and

motivational benefits of using the online platform to

practise their writing, evaluate their peers’ work and

learn from one another. What merits further and

more in-depth investigation is nonetheless individual

teachers’ management of the web-based

collaborative platform, their strategy use in

facilitating peer interaction, their approach to

feedback and their tolerance of the use of L1.

As Engstrom and Jewett (2005) assert, the

effectiveness of wiki application in learning and

teaching depends on “careful planning and training

of both students and instructors to familiarize them

with the technology”. A systematic approach

coupled with a pedagogically informed plan is of

vital importance to the successful integration of this

technology into the curriculum of any second or

foreign language.

REFERENCE

Alexander, B. 2006. Web 2.0 – a New Wave of Innovation

in Teaching-learning. Retrieved from http://net.educaus

e.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERM0621.pdf

Boulos, M. N. K., Maramba, I., & Wheeler, S. 2006.

Wikis, blogs and podcasts: a new generation of

Web-based tools for virtual collaborative clinical

practice and education. BMC Medical Education, 6(41).

Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-69

20/6/41

Engstrom, M. E., & Jewett, D. 2005. Collaborative

learning: The wiki way. TechTrends, 49(6), 12-15.

Goldberg, A., Russell, M., & Cook, A. 2003. The Effect of

Computers on Student Writing: A Meta-analysis of

Studies from 1992 to 2002. The Journal of Technology,

Learning, and Assessment, 2(1), retrieved from http://es

cholarship.bc.edu/jtla/vol2/1/.

Hossain, M., & Aydin, H. 2011. A Web 2.0-based

Collaborative Model for Multicultural Education,

Multicultural Education & Technology Journal,

5(2),116 – 128

Lo, J., & Hyland, F. 2007. Enhancing Students'

Engagement and Motivation in Writing: The Case of

Primary Students in Hong Kong. Journal of Second

Language Writing, 16, 219-237.

Nunan, D. 1999. Second language teaching & learning.

Boston, Mass: Heinle and Heinle Publishers.

Parker, K. R., & Chao, J. T. 2007. Wiki as a Teaching Tool.

Learning, 3(3), 57-72. Citeseer. Retrieved from http://

scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=in

title%3AWiki+as+a+Teaching+Tool#0

Richardson, W. 2006. Blogs, wikis, podcasts and other

powerful web tools for cClassrooms. Thousand Oaks,

CA: Corwin Press.

Sze, P. 2010. Online Collaborative Writing Using Wikis.

Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Sze-Wikis.

html

Tribble, C. 1996. Writing. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Wheeler, S., Yeomans, P., & Wheeler, D. 2008. The good,

the bad and the wiki: Evaluating student-generated

content for collaborative learning. British Journal of

Education Technology, 39(6), 987-995.

White, R. & Arndt, V. 1991. Process writing. London:

Longman.

Wiliam, D. 2005. Assessment for Learning: Putting it into

Practice. SETT – The Scottish Learning Festival,

Transforming Professional Practice, Glasgow, UK,

September, 2005.

Witbeck, C. 1976. Peer Correction Procedures for

Intermediate and Advanced ESL Composition Lessons.

TESOL Quarterly, 10(3), 321-326. Retrieved from

http:// www.jstor.org/stable/3585709

Woo, M., Chu, S., Ho, A., & Li, X. 2011. Using a Wiki to

Scaffold Primary-School Students' Collaborative

Writing. Educational Technology & Society, 14

(1),

43–54.

Woo, M., Chu, S., Ho, A., & Li, X. 2009. Collaborative

Writing with a Wiki in a Primary Five English

Classroom. Proceedings of the 2009 International

Conference on Knowledge Management [CD-ROM].

Hong Kong, Dec 3-4, 2009.

Zammit, K. 2010. Working with Wikis: Collaborative

Writing in the 21st Century. IFIP Advances in

Information and Communication Technology, 324,

447-455.

CSEDU2012-4thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

222