Schools as Organizations

A Semiotic Approach towards Making Sense of Information Technology

Elaine C. S. Hayashi

1

, M. Cecília Martins

2

and M. Cecília C. Baranauskas

1,2

1

Institute of Computing, UNICAMP, Campinas, Brazil

2

NIED, UNICAMP, Campinas, Brazil

Keywords: Human-computer Interaction, Participatory Design, Organizational Semiotics, Educational Technology.

Abstract: Low cost educational laptops have the potential of transforming educational practices in the public schools

from developing and emerging countries. However, in order to be effectively incorporated into schools’

daily practices, technology has to make sense to the people that constitute these schools. This paper reports

on the initial activities with the members of an elementary public school in Brazil, facing the challenge of

constructing meaning for a new digital artefact. Concepts and practices from Organizational Semiotics (OS)

and Participatory Design (PD) were adapted as a methodological frame of reference for the analysis of

structure and context. Preliminary results indicate that, although originally designed for the business and

work domains, practices from OS and PD were suitable and revealed information that other approaches

would hardly reveal, regarding a prospective use of technology in educational contexts.

1 INTRODUCTION

Technology is everywhere in our lives, mediating

our actions. Hence, the use of technology should be

a powerful tool to provide access and to promote the

construction of knowledge in the schools. This is

especially true in the context of developing

countries, where the opportunities of access to

digital technology at home are scarce. However, to

be incorporated into schools’ practices, it needs to

make sense to the community of users. Technology

use should be transparent, providing teachers and

students with learning opportunities, so that a digital

culture might be created at school and perhaps

disseminated to the schools’ physical surroundings.

According to a survey conducted by the

Brazilian’s National Institute for Educational Studies

Anísio Teixeira – INEP; and the Brazilian Ministry

of Education and Culture – MEC (MEC/INEP,

2010) roughly 31,700,000 students are enrolled in

the fundamental level, from which around

27,500,000 are in public schools. A survey

conducted by the Brazilian Internet Steering

Committee - CGI (CGI, 2010) indicated that while

81% of Brazilian public schools (including

fundamental level and high schools) have a

computer lab, only 4% of the public schools have a

computer in the classroom.

Recently, a program from the national

government has proposed the use of educational

laptops in a 1:1 model and has been incrementally

distributing the machines to public schools. The

mobility of the laptop allows students to take it to

their homes, extending the potentials of the laptop to

the students’ family. In a country where 55% of the

population in general have never used a computer

(UNESCO), that initiative might represent a relevant

step towards more access to information and

knowledge, i.e., a fairer society.

For a new digital technology to be effectively

incorporated in educational contexts, it must make

sense to all involved parties and it must consider

their habits, abilities and organizational culture. On

that ground, we believe that the process of bringing

this new artefact of technology to the school context

must happen under a socio-technical approach. This

situation presents the research challenge of

formalizing models and techniques to promote

understanding of the situated scenario towards

meaningful use of technology in schools.

In January 2009, 500 XO laptops were donated

by the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) organization

and are being used at a school in the suburban area

of the city of Campinas, in São Paulo. This project is

a research effort that runs in parallel and

independently to other government’s initiatives. In

15

C. S. Hayashi E., Martins M. and C. Baranauskas M..

Schools as Organizations - A Semiotic Approach towards Making Sense of Information Technology.

DOI: 10.5220/0003995900150024

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2012), pages 15-24

ISBN: 978-989-8565-12-9

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

the approach adopted by the government, to insert

the laptops at schools, a same methodology is

imposed to all the schools from different regions of

the country. Differently, our approach acknowledges

the situated character of the problem and constructs

a methodology based on a joint effort of the different

parties involved: researchers, designers, developers,

educators, school staff, and students.

Taken the school as a complex organization, the

frame of reference to our work is based on methods

and artefacts of the Organizational Semiotics (OS)

(Stamper, 1993 and 1993b), combined with

techniques inspired by Participatory Design (PD)

(Muller, 1993). Both OS and PD are articulated to

compose the collaborative practices of Semio-

participatory Workshops (SpW) (Baranauskas,

2009) conducted within the school.

This paper presents our findings from the initial

stages of the process of clarifying the problem of

technology embedding in a fundamental public

school in Brazil, on the grounds of OS. The paper

captures the impacts of the SpW based methodology

and discusses results of the first workshop. Five

other workshops were conducted in the school

during the year 2010 and four in 2011. The paper is

organized as follows: related approaches are

reviewed in Section 2. Theoretical and

methodological framework adopted by the project is

detailed in Section 3. Section 4 describes the

planning of the workshop. The workshop itself, with

its results and discussion, is detailed in Section 5.

Section 6 concludes.

2 RELATED WORK

Since the proposal of the XO laptop by the OLPC in

2005, many initiatives have taken place to

investigate its use at schools. Not only the XO

laptop is being target of studies, but also similar

technology that has been proposed after OLPC.

From a pure technical perspective, Moody and

Schmidt (2004) present the advantages of wireless

networks in education and numerate some concerns

to be addressed before the wireless networks are

implemented at schools.

From a socio-technical perspective, Cervantes et

al. (2011) analysed the social and technical

infrastructures that support the use of low cost

laptops at schools. That was done by observing the

activities that took place at elementary schools in

Mexico after the laptops were already distributed.

The authors described, based on what they saw in

the schools, how the available infrastructures (both

from technical and human perspectives) shaped the

use of the laptops.

Also describing the laptops use after its

implementation, Flores and Hourcade (2009) report

on the experience in Uruguay. The government in

Uruguay has distributed laptops to every child in the

public elementary school of grades 1-6 in the

country. The authors describe the first year with the

laptops at the schools.

In the Brazilian context, Corrêa et al. (2006)

conducted surveys similar to market researches.

Qualitative (interviews) and quantitative (forms)

approaches supported the investigation on the

acceptability of low cost laptops among teachers and

students before introducing the laptops to the

interviewees. This descriptive study collected and

reported on teachers’ and students’ beliefs on the

impacts of digital technology at school.

The important difference between the approach

of Corrêa et al. and ours lays on the role that

teachers and students play in the project. Instead of

passive informants, we take teachers, students and

other members of the social organization formed by

the school, as active partners. More than eliciting

participants’ concerns, our objective is to promote a

collective awareness, encouraging a collaborative

prospection of ideas and solutions, creating together

more meaningful uses of digital technology, even

before the arrival of that technology.

Expanding from the situated context of

educational laptops to the general use of Information

and Communication Technologies (ICT) in

educational settings, Lim (2002) also argued for the

importance of taking socio-technical perspectives.

Based on the Activity Theory, the author proposes a

theoretical framework that shows the connection of

ICT with learning and the sociocultural setting. The

garden-as-culture metaphor from Cole (apud Lim,

2002) is adopted to provide a broader view of the

school and educational system in the society at large.

Although OS is not mentioned, the author’s

(Lim, 2002) figure displays some ideas that are

similar to those present on OS artifacts: in the

framework from Lim, the garden metaphor with the

activity system is shown as embedded circles, with

the society as the outermost circle. Those more

formal structures are on inner circles; and the

activity system itself as the innermost circle.

Explicit reference to OS is made in the work of

Melo et al. (2008). Different design techniques and

artifacts are combined into the model that the

authors propose for the design centred in children’s

participation. The work of Melo et al. (2008) had its

focus on the process of design for and with children

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

16

towards interfaces that made more sense to the

children

Our work faces the challenge of providing more

meaningful appropriation of technology within a

school community. The simple injection of a foreign

technical device into a community’s life seems

easier but the adjustments demanded by this

approach might feel less natural. Our pursuit aims at

promoting a collective construction of meanings

towards more natural housing of the new

technological tool, having the entire community –

with teachers, students and other members – as

actors.

In this endeavour, we adopted a theoretical and

methodological reference based on Organizational

Semiotics (OS) and Participatory Design (PD). Even

though both OS and PD have origins in industrial

and business areas, we argue that they can be

successfully applied in educational contexts, guiding

the process of technology assimilation to more

meaningful results. The principles and some

instruments from OS and PD applied in this project

are detailed in the next section.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Organizational Semiotics

OS views information systems as organisations,

composed of socially established models of

behaviour, beliefs, perceptions and values (Stamper

et al., 2000). In this approach, the design of

technology starts with the understanding about the

sense that the community of users make of signs and

how the organisation is structured.

According to Stamper et al. (2000), any

organisation can be described in terms of the norms

that govern the behaviour of that social group. The

authors suggest that such norms are applicable to

different types of taxonomies. One possible

categorization is by the level of formality of the

norms. In this case, the categories are: technical,

formal and informal. Strictly precise norms that can

be expressed as instructions to be followed by, for

instance, a computer, comprise the technical norms.

The written norms (i.e., bureaucracy) are the formal

ones; and all other norms that people know and live

according to are the informal. These levels can be

represented as the layers of an onion, where the

technical systems are embedded inside the formal

and informal organisation. The Semiotic Onion

(Stamper, 1993b) comprise the technical, formal and

informal layers of real information systems.

Another possible way proposed by Stamper et al.

(2000) to classify norms is according to their role in

relation to signs and their functions, which can be

organized using the Semiotic Framework (Stamper,

1993). The authors indicate that this taxonomy helps

understanding the impact of information technology

when that technology is the cause of organisational

change. The Semiotic Framework from Stamper

organises the properties of the signs into six levels

(three more levels than the usual semiotic division of

syntax, semantics and pragmatics):

Social level: for a sign to be fully understood, as

argued by Stamper (1993), one needs to understand

its potential or actual social impacts. That includes

concerns about ways of behaving, sets of values,

shared models of reality, etc.

Pragmatic level: for a sign to have a use, it must

have an intention, shared by its creator and its

interpreters. This level involves the understanding of

context and forms of communication.

Semantic level: this level is related to the

meanings that are continuously constructed and

reconstructed while people use syntactic structures

to organize their actions.

Syntactic level: concerns formal structures that

maps or transforms symbolic forms. These are

mechanical transformations and they are proper of

software developers.

Empiric level: this level includes the aspects

related to telecommunication in general: noise,

patterns, redundancy, errors, channel capacity, etc.

Physical level: the physical properties of objects

or events: equipment, hardware, physical structures,

etc.

Together, the layers of the Semiotic Framework

(also Semiotic Ladder) guide the understanding of

how an organisation works. Moreover, it helps in

analysing factors that might contribute to more

successful processes (Liu, 2000; Stamper, 1993).

In the next sections we exemplify the use of the

Semiotic Onion and the Semiotic Framework for the

analysis of data collected from the activities in the

school. Next we briefly describe two other artefacts

that were explored collectively during the

encounters with the community of users.

3.1.1 Stakeholder Chart

The various methods that compose MEASUR

(Methods for Eliciting, Analysing and Specifying

Users’ Requirements), proposed by Stamper (1993),

provide tools for better understanding organizations.

Liu explains that, even when dealing with rather

SchoolsasOrganizations-ASemioticApproachtowardsMakingSenseofInformationTechnology

17

chaotic problem situations, the methods allow

gradual and precise clarification, until a set of

technical solutions can be reached.

The Stakeholder Analysis Chart

(SC) is one of

the Problem Articulation Method techniques, from

MEASUR (Liu et al., 2007). The actions of

stakeholders, with their roles, interests and

responsibilities, usually impact the result of a

project. Because of that, it is important to clearly

identify who the stakeholders are so that they are

properly taken into account in the process.

3.1.2 Evaluation Framing

The Evaluation Framing (EF) (Baranauskas et al.,

2005), differently from the Valuation Framing (Liu,

2001), is a technique that aids in the process of

anticipating problems new technology might bring

to the organisation, and prospecting solutions for

them. The EF guides a reflection on issues and

possible ideas and solutions related to each category

of stakeholders raised through the SC. In the

workshops that we describe in this paper we have

used the EF to help the whole group in the

identification of the main issues related to this

specific context of new technology and educational

change.

3.2 Participatory Design

The Participatory Design (PD) has its origins in

Scandinavia in the late '70s, appearing in the

workplace to promote more democratic insertion of

technology among those more affected by it (Schuler

and Namioka, 1993). Brought to the design context,

the involvement of the users in the design process

contributes to the motivation of participants and to

greater satisfaction with the outcome, since all are

co-authors of the resulting system.

Several techniques have been proposed to allow

this interaction between designers and end users, and

to allow the participation of users in all stages of the

design process. Among the techniques used in PD,

we can mention games, plays and different levels of

prototyping. Muller brought together and listed

several of these activities in (Muller, 1993).

3.3 Semio-participatory Workshops

The insertion of digital artifacts in the educational

environment demands a vision of its socio-cultural

context (Lim, 2002).

The articulation of methods from OS with

principles and practices from DP represents a

powerful tool for the process of understanding the

social context while involving the target community

in the course of actions. This articulation was

materialized in activities that were carefully tailored

for each community who joins the SpW

(Baranauskas, 2009).

OS was proposed in the context of information

systems and business organisations. PD has also its

origins in the work field contexts. However, the

combination of OS and PD has shown important

results in other knowledge domains and practice

areas. For example, Neris el al. (2011) report their

actions during the design of an inclusive social

network, involving a community of young adults

and seniors from a low-income neighbourhood.

Other successful examples include practices related

to the domains of critical systems (Guimarães and

Baranauskas, 2008), geographic information systems

(Schimiguel et al., 2005); (Escalona et al., 2008),

iDTV (Furtado et al., 2009), among others.

Those results encourage us to use the presented

methodological frame of reference to bring

awareness and collective discussion within an

educational organisation, involving school-age

children and their fellows (teachers, parents and

other members of the school). Together, we have

been engaged in the process of constructing a more

meaningful use of technology. The next section

describes how these methods and artefacts have been

collaboratively articulated in our scenario.

4 PRELIMINARY PRACTICE

The first encounter with the school’s community

took place even before the arrival of the laptops at

the school. Researchers from different areas

(computer science, pedagogy, multimedia,

psychology, etc.) gathered with the members of the

school, which included teachers, students, parents

and other employees from the school (e.g., principal,

pedagogue, cook, janitor). Also representatives from

the secretary of education of the city hall were

present. This first SpW had 60 participants and the

composition of this group is represented in Figure 1.

The discussion on the new technology that was

about to be used at the school would be richer if the

participants could have a better idea about that

technology. Because of that, the SpW started with

what was called the “XO Mini Fair”.

The mini fair allowed participants to have their

first contact with the XO laptop. For this event, eight

XO laptops were distributed among four stands. In

the first stand, participants had the chance to

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

18

manipulate the laptop, finding out how to open it,

how to close it, use the antennas, rotate the screen.

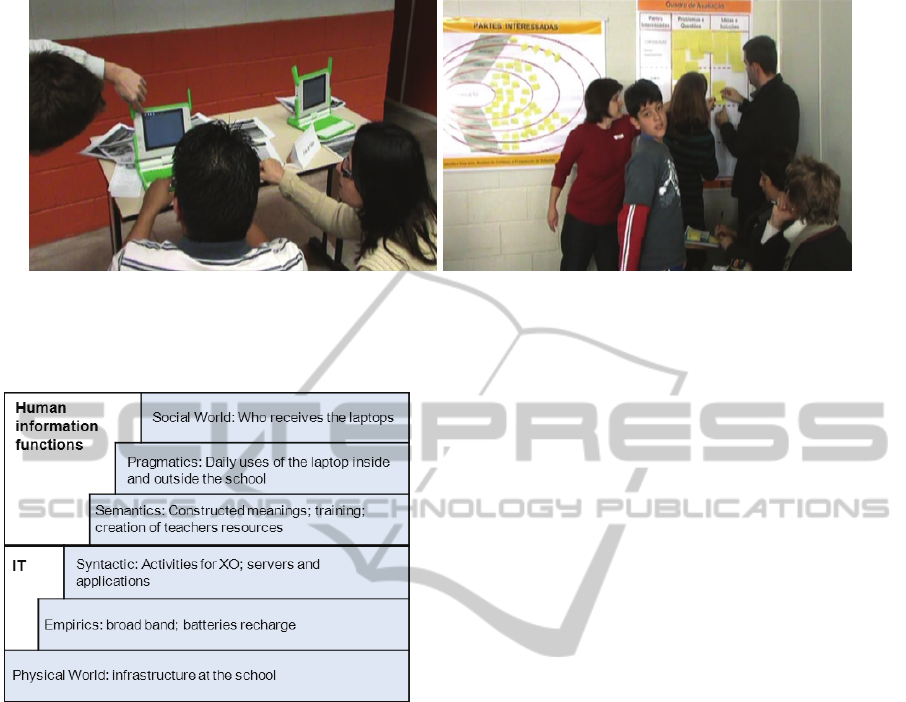

Figure 1: Participants of the SpW and their roles.

At another stand, the features of XO’s webcam

were explored in activities where participants were

able to take pictures and make short videos. The

other two stands examined the chat activity and the

educational game SOO Brasileiro (Silva et al.,

2008). Figure 2(a) illustrates a moment of this

activity in one of the stands.

Each stand had at least one facilitator, i.e., one of

the researchers who would be available to assist

participants in their interactions with the XO

whenever needed.

After the XO Mini Fair, the whole group

gathered together again and videos were presented.

The first video was composed of extracts that

formed a shorter version from a video available on

Youtube

(http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZwQOibphtjc).

This video showed the experience that a public

school in another State in Brazil was having with the

use of XO laptops. The second video presented some

of the initiatives from our research group related to

low cost laptops and the main features of the XO

laptops.

After all participants were familiar with the

laptop and some of its possible uses, they were

invited to discuss, in smaller groups, about the

impacts of bringing that technology to the school.

Posters had been previously prepared, depicting the

empty artifacts of SC and EF. Due to the size of the

group (60 people), they were distributed in three

smaller groups. Each group had one poster of each

artifact; and participants expressed their thoughts

writing in post-it’s that would be fixed on the

posters. In each group, a facilitator led the activity,

eliciting responses and attaching the post-its on the

charts. Figure 2(b) illustrates a moment of this

activity.

After all charts were created, the entire group got

together again and the results were discussed; each

group summarized their results on the activities.

Towards the end of the SpW, participants were

invited to take a moment of introspection. They were

asked to write, individually and anonymously,

adjectives or complete sentences that reflected their

perceptions and expectation about the project. The

activity was not mandatory, but the majority

reported on their impressions.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The XO Mini Fair was an attempt to diminish

participant’s anxieties about the technology they

were going to receive in the school. Participants

visited all stands and learned how to manipulate the

laptop and how to use some of its main features.

After the SpW, researchers analyzed the material

produced during the workshop. The tables that were

filled separately by all three groups were combined

into one consolidated table.

The charts displayed participants concerns

related to varied subjects: safety issues (e.g.,

precaution and protection of children carrying a

laptop from home to school and vice-versa); training

(e.g., how to train teachers, students, parents and

other users); operational issues (e.g., how and where

to store all machines, how to distribute them among

the children, maintenance issues); among others.

Figure 3 illustrates the main issues discussed in the

groups, represented and sorted according to the

levels of the Semiotic Framework. By observing the

summarized general results of the SpW in Figure 3,

we can realize how the use of SC and EF helped the

group to become aware of issues ranging from the

physical to the social domains. Technology related

projects are usually directed mainly towards the IT

levels (physical, empirics and syntactic levels of the

Semiotic Framework). In the context of our project,

the concerns with human information functions (the

social, pragmatic and semantic levels) are of vital

importance. For the technology deployed to make

sense, and thus be incorporated into community

practices, it is necessary to address issues of higher

levels of the framework as well as the issues related

to the lower levels. For example, since the number

of students in the school exceeds the number of

machines, deciding how to distribute the laptops will

have an impact in the schools’ culture and habits.

The infrastructure of the schools (e.g., number of

sockets at a classroom, electric capacities, etc.) may

SchoolsasOrganizations-ASemioticApproachtowardsMakingSenseofInformationTechnology

19

Figure 2: On the left, (a) participants of the SpW examining the XO at the mini fair; and (b) one of the groups constructing

the Evaluation Framing with post-it’s.

influence the daily uses of laptops.

Figure 3: The Semiotic Framework (Liu, 2000) organizing

the main ideas related to the project.

Figure 3 will be further discussed later in this

section. Following, more details on the results from

the workshop is presented.

5.1 Findings from the Artifacts

The SC was originally designed to be used by the

developers of informational systems themselves

(Kolkman, 1993). In our approach, the artifacts were

used collaboratively in a participatory practice

during the SpW, where researchers and the school’s

community interacted together. All participants

recognized themselves as protagonists in the action

of deploying low cost educational laptops at the

school.

5.1.1 The Stakeholders Analysis Chart

The different groups presented similar results and

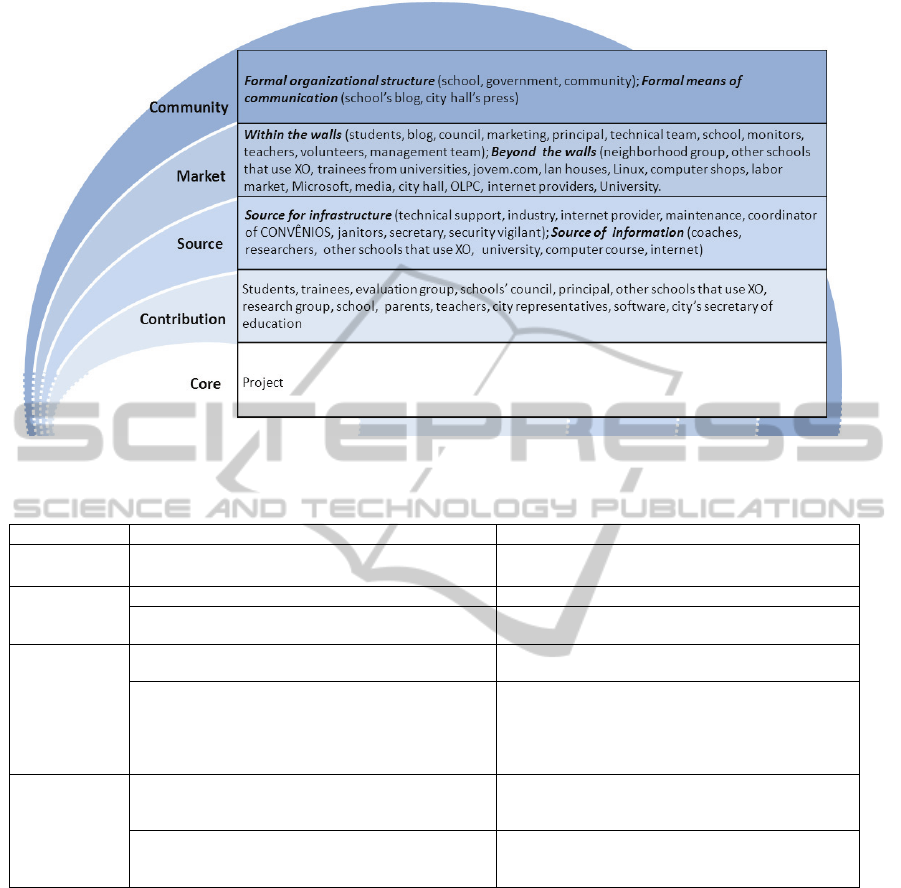

they are summarized in Figure 4. On the

background, the figure shows part of the model of

Stakeholders Analysis (Liu, 2001); and the table on

the foreground shows the main stakeholders elicited.

The contribution layer lists those directly

involved in the course of action. The core of the

analysis was the Project as a whole. Besides those

that are part of the this school’s community, also

other schools were listed on this layer. Those

schools that have already been experiencing with the

use of educational laptops were seen as possible

contributors, as a source for inspiration and example.

For the source layer, the list of possible suppliers

and clients elicited during the SpW was divided in

two categories: those who could be a source of

information for the project and those who would

provide the necessary material infrastructure.

Also the responses for the market layer were

grouped in two categories: the collaborators or

competitors from within the school’s walls, and

those from beyond the school’s walls. This

illustrates how participants are able to see beyond

their own and near environment, understanding that

the impact of the Project might extend beyond the

school itself.

Due to time limits, and also due to the rich

discussions raised on these first layers, some of the

groups were not able to discuss the outer layer

related to bystanders and community. Nonetheless,

the few responses concerned basically the possible

formal means of communication from the

community outside the school and other formal

organizational structures.

5.1.2 Evaluation Framing

After identifying who were the agents that either

would be involved in or affected by the project, the

same groups discussed the issues and possible ideas

related to each layer of stakeholders. The complete

transcription of the issues and ideas raised summed

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

20

Figure 4: Summary of the results constructed with the Stakeholders Analysis Chart.

Table 1: Examples of the ideas elicited by the use of the Evaluation Framing.

Stakeholders Issues Ideas and Solutions

Community What is the government’s role in the project?

Technical support from the Municipal Education

Secretary

Market

How to provide internet access to the laptops? Extend wireless network.

Publicity: how to spread the word about the project?

Write reports about the experience;

Use the school’s official blog.

Source

How to provide training to staff for the usage of the

laptops in the school?

Student monitors as assistants.

Maintenance: how to fix software and/or hardware

problems?

Provide specific courses for teachers, students and

other interested in helping with the maintenance of

the laptops;

Search for agreements with partners from outside the

school.

Contribution

Distribution of the laptops: since the amount of

teachers/students is greater than the amount of

available laptops, who receives the laptops?

Share laptops among siblings; share laptops among

children from different shifts.

Children’s safety: is it safe for the children to go

home carrying a laptop? Would the parents allow it?

Parents signing a Terms of Conditions of Use;

Meeting with parents; Parents accompanying

children to and from school.

more than five pages of texts. Table 1 lists one

example of issue and possible solution related to

each layer of stakeholders.

The concern with the distribution of the laptops

among students and teachers prevailed in all groups.

The school has more than 500 students, plus more

than 30 teachers; and there were around 500 laptops

available to be shared among them. Different ideas

were discussed, including: sharing laptops among

siblings or among children from different shifts (at

this school, grades 1-5 attends the morning shift,

while grades 6-9, the afternoon’s).

Regarding the stakeholders from the source layer

– in this case, more specifically, source of

information – some participants discussed about the

learning curve and who would provide teachers with

the necessary training.

5.2 Expectation and Perceptions

The adjectives and sentences written at the end of

the workshop portray the beliefs, expectation and

perceptions that participants had about the project

and the XO laptop. The full transcript of participants'

expectations, as well as the transcription of all issues

and ideas elicited, shall be available on a technical

report.

From the transcription of participants’

SchoolsasOrganizations-ASemioticApproachtowardsMakingSenseofInformationTechnology

21

expectation and perceptions, a tag cloud was created.

Figure 5 illustrates the words and their occurrence

(how frequently the words appear in participants

reports).

As the project was at the core of the discussion,

the word “project” was the most mentioned one, and

it was taken away from the list so that all other less

mentioned words would be readable in the resulting

tag cloud. Positive adjectives were also frequently

mentioned, e.g., “great” and “good”. The general

opinions expressed revealed participants’ interest

and excitement for the new arrival, which was

denoted by terms like “interesting”, “innovative”,

“challenging”, “motivation”, “cool”, “fantastic” and

“happy”.

Albeit naïve, one hoped for changes to “better

lives” simply by the presence of the laptop itself.

Others demonstrated being aware that the proper use

of the laptops might promote deep changes in the

school, changing paradigms and impacting the entire

school’s systems; and they were also aware that this

does not happen overnight, but instead, as a result of

a long process that demands conjoint actions

(“Innovative, however, a long path lays ahead before

being totally functional”; “(…) interesting, but

demands more detailed planning to work (…)”;

“(…) if well organized (…) a mechanism to promote

the involvement of the community with the school.”)

From the 60 participants, two questioned the

outcome or purpose of the project. One concern was

with the improper use of the internet. The other

made use of a metaphor from the bible, questioning

whether the project was not trying to “throw pearls

to pigs”.

5.3 Analysis Summary

The insertion of the laptops that was about to take

place at the school was an act that would take place

at the technical layer of the Semiotic Onion. This

occurrence would demand that norms be created at

the school to rule the use of the laptops at the six

levels of the Semiotic Framework, as summarized

earlier in this paper on Figure 3.

5.3.1 Social Level

From a social level perspective, one of the rules that

needed to be decided regarded sharing laptops: who

would share the laptops and how was it going to be

controlled. One idea that was positively taken by

most of the adult participants was sharing the laptop

among siblings. It seems feasible and practical that if

brothers and sisters attend the same school, in

different grades and shifts, they could perfectly

share one laptop. That idea, however, would not

work in practice. Students revealed that the

relationship they actually have with their brothers

and sisters is not always friendly enough to keep that

norm working well.

If the norm (formal layer) about sharing the

laptops among siblings were decided and

implemented without accounting children’s opinion,

conflicts might had led to a disruption at the social

level (the social level of the Semiotic Framework, in

this context, can also be seen as the informal layer of

the Semiotic Onion).

The involvement of the children in the decision

processes are important not only to guarantee that

aspects from real live practices are accounted, but

also because they – the children – are central to the

entire project. The meaning the children, together

with other members of the school, will make of the

laptops will have social consequences and might

determine the success or failure of the project.

As Liu (2000, p.111) argues: “Before

introducing an IT system, there should be clear

specifications of rules for business operations”.

These rules must make sense to those involved: “an

IT system presupposes a formal system, just as a

formal system relies on an informal system”.

5.3.2 Pragmatic Level

At a pragmatic level, the use of the laptops

should provide richer learning environment,

promoting improved education. Another issue raised

during the SpW regarded the lack of knowledge

teachers had on the laptop. One of the ideas

suggested that students who were more familiar with

digital technology could provide support to peers

and to the teachers. This approach might contribute

to an important change: moving away from the

instructional paradigm, towards more

constructivist/constructionist (Papert, 1993) ones.

Learning about specific features of the laptop

only for the purpose of learning about that

technology might make less sense than engaging on

the construction of knowledge supported by the use

of the technology.

5.3.3 Semantic Level

In this process, the meanings that will be constructed

(and reconstructed, in a continuous and iterative

process) have an important role. “The meaning of a

sign relates to the response the sign elicits in a given

social setting”; moreover, it “frequently suggests

mental and valuational processes as well” (Liu,

2000, p.30). Children might understand the laptops

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

22

Figure 5: Tag cloud formed with participants' adjectives and sentences about the project.

as a source of distraction and recreation. This can be

a powerful learning tool if teachers choose to take

advantage of what children most like doing at the

laptop in order to create learning opportunities. On

the other hand, recreational activities might be

considered harmful and forbidden

Some of the sentences written at the end of the

SpW suggested that it is important to discuss and

review pedagogical projects, policies and practices

of the school. Indeed the construction of meaning

from the uses of the laptop might promote changes

which will demand that norms be adjusted to the

new reality.

5.3.4 Syntactic, Empiric and Physical Levels

The lower levels of the Semiotic Ladder provide

support to the higher levels. The syntactic level

houses concerns on properly understanding the rules

(of interaction) that allows the use of the laptops.

The operational system and the activities

(applications) from the XO laptop have interaction

metaphors that differ from the ones we usually see in

personal computers or regular laptops. These

differences might confuse those who are familiar to

other computers’ interaction language, but will be

overcome as long as the activities are intended to a

practical and meaningful use.

The last two levels, physical and empirical, are

usually not the concern of users. However, they are

important concerns and they were discussed by all

groups. Although the XO laptop has the Mesh

network that supports communication among the

laptops even when no Internet connection is

available, participants were concerned with wireless

Internet access. Another concern was with the

availability of enough electrical sockets to recharge

all laptops in the classrooms. Such concerns were

easily addressed and solved.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Schools are complex social organizations that shape

the future of generations. The insertion of a

technological innovation within the school should

not happen with the deterministic belief that

technology develops autonomously and by its own

logic. The belief should be towards an environment

that is continually reconstructed in communicative

practices among participants (mediated by

technology). The Semio-Participatory approach,

grounded in the Organizational Semiotics concepts,

helped the group to face the challenge of changing

old concepts. One of them is the concept that the

school has to adapt itself to technological progress.

Instead, the school is an organization that is capable

of influencing the technological innovation, inside

and outside its walls.

In the initial phase of the XO Project, the first

Semio-participatory Workshop sought to clarify the

problem and handle with general expectation about

the project. The activities, guided by artifacts

inspired from OS and PD, allowed the group to line

up the different views (viewpoints of researchers,

students, teachers and school staff) on the

deployment of a new digital technology at an

elementary public school in Brazil.

The SpW helped participants to have a broader

view of the Project, and to articulate issues, ideas

and solutions. Taking a participatory approach to

this analysis was essential. This paper described the

process of conducting the SpW, illustrating its

planning, implementation, results and analysis.

The results indicated that the referential basis

SchoolsasOrganizations-ASemioticApproachtowardsMakingSenseofInformationTechnology

23

and artifacts from OS and PD are appropriate tools

for guiding a collective construction of meanings

and norms regarding the introduction of a new

information technology at an educational

organization. Further work involves a reflection on

the impact of such approach after 2 years of the

project in the school.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank CNpQ (processes# 143487/2011,

475105/2010-9 and 560044/2010-0) for financial

support; our colleagues from UNICAMP and EMEF

Padre Emílio Miotti.

REFERENCES

Baranauskas, M. C. C., Schimiguel, J., Simoni, C. A. C.,

Medeiros, C. M. B. (2005) Guiding the Process of

Requirements Elicitation with a Semiotic Approach

In: Proc. of HCI International, v.3., p.100 – 111.

Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2009) Socially Aware Computing,

In: Proc. of ICECE 2009, 1-5.

Bonacin, R., Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2003) Semiotic

Conference: Work Signs and Participatory Design. In:

10th HCI International, pp. 38-43.

Cervantes, R., Warschauer, M., Nardi, B., Sambasivan, N.

(2011) Infrastructures for Low-cost Laptop Use in

Mexican Schools. In: Proc. of CHI’11, pp. 945-954.

CGI (2010) ICT Education 2010: Survey on the use of

information and communication technologies in

Brazilian Schools. Available at: http://www.cetic.br/

tic/provedores/index.htm (last accessed: Feb. 2012).

Corrêa, A. G. D., Assis, G. A., Ficheman, I. K., Venâncio,

V., Lopes, R. D. (2006) Avaliação de Aceitabilidade

de um Computador Portátil de Baixo Custo por

Criança. In: Proc. of SBIE, 2006.

Escalona, M. J.; Torres-Zenteno, A.; Gutierrez, J.;

Martins, E.; Torres, R. S.; Baranauskas, M. C. C.

(2008) A Development Process for Web Geographic

Information System. In: ICEIS 2008, pp. 112-117.

Flores, P., Hourcade, J.P. (2009) One Year of Experiences

with XO Laptops in Uruguay. In: Interactions, v. 16

(4), p. 52-55.

Furtado, M. E. S.; Kampf T.; Piccolo, L. S. G.;

Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2009) Prospecting the

Appropriation of the Digital TV in a Brazilian Project.

In: Computers in Entertainment, v. 7, p. 10-32, 2009.

Guimarães, M. S.; Baranauskas, M. C. C.; Martins, E.

(2008) Communication-based Modeling and

Inspection in Critical Systems. In: ICEIS 2008, v.

HCI, pp. 215-220.

Lim, C. P. (2002) A theoretical framework for the study of

ICT in schools: a proposal. In: British Journal of

Educational Technology, v. 33(4), 2002, pp.411 – 421.

Liu, K. (2000) Semiotics in Information Systems and

Engineering, Cambridge University Press.

Liu, X. (2001) Employing MEASUR Methods for Business

Process Reengineering in China, PhD Thesis

University of Twente. The Netherlands: Grafisch

Centrum Twente, Enschede.

Liu, K., Sun, L., Tan. S. (2007) Using Problem

Articulation Method to Assist Planning and

Management of Complex Projects. In: Project

Management and Risk Management in Complex

Projects 2007, Part 1, 3-13.

Melo, A. M.; Baranauskas, M. C. C.; Soares, S. C. de M.

(2008) Design com Crianças: da Prática a um Modelo

de Processo. In: Revista Brasileira de Informática na

Educação, v. 16 (1), p. 43-55, 2008.

MEC/INEP. Resumo técnico - censo escolar 2010.

Available at http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?op

tion=com_docman&task=doc_download&gid=7277&

Itemid= (last accessed: Feb., 2012)

Moody, L., Schimidt, G. (2004) Going wireless: the

emergence of wireless networks in education. In:

Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges, v. 19 (4),

pp.151-158.

Muller, J. M. (1993) Participatory Design. In:

Communications of the ACM, vol. 36, issue 6.

Neris, V. P. A., Almeida, L. D., Miranda, L. C., Hayashi,

E. C. S., Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2011) Collective

Construction of Meaning and System for an Inclusive

Social Network. In: International Journal of

Information Systems and Social Change (IJISSC).

OLPC. http://one.laptop.org/ (last accessed in Jan. 2012).

Papert, S. (1993) The Children's Machine: Rethinking

School In The Age Of The Computer. HarperCollins.

Schimiguel, J., Melo, A. M., Baranauskas, M. C. C.,

Medeiros, C. M. B. (2005) Accessibility as a Quality

Requirement: Geographic Information Systems on the

Web. In: Proc. of CLIHC'05, pp. 8-19.

Schuler, D. & Namioka, A. (1993) Participatory design:

Principles and practices. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Silva, B. F., Romani, R., Baranauskas, M. C. C. (2008)

SOO Brasileiro: Aprendizagem e Diversão no XO. In:

Revista Brasileira de Informática na Educação, v. 16

(3), pp. 29-41.

Stamper R. K. (1993) Social Norms in requirements

analysis – an outline of MEASUR. In Requirements

Engineering, Technical and Social Aspects. Academic

Press.

Stamper, R. K. (1993b). A Semiotic Theory of

Information and Information Systems / Applied

Semiotics. In: Invited Papers for the ICL/University of

Newcastle Seminar on "Information", Sept., 6-10.

Stamper, R., Liu, K., Hafkamp, M., Ades, Y. (2000)

Understanding the Roles of Signs and Norms in

Organisations: A semiotic approach to information

systems design. In: Journal of Behaviour &

Information Technology, vol. 19 (1), pp.15-27.

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

24