Keeping Values in Mind

Artifacts for a Value-oriented and Culturally Informed Design

Roberto Pereira, Samuel B. Buchdid and M. Cecília C. Baranauskas

Institute of Computing, University of Campinas, Av. Albert Einstein N1251, Campinas-SP, Brazil

Keywords: Design, Organizational Semiotics, VIF, CARF.

Abstract: Identifying, understanding and explicitly involving values and cultural aspects of stakeholders have been

regarded as a challenge in the design of interactive systems. There is still a lack of principled and light-

weight artifacts, methods and tools for supporting designers in this task. In this paper we propose two

artifacts for supporting designers in making explicit both stakeholders’ values and system’s requirements

taking these values into account. A case study reports the use of the artifacts in the design of seven

prototypes of applications for the Brazilian Interactive Digital Television. The artifacts showed to be

promising for supporting designers in the complex scenario of designing value-oriented and culturally aware

interactive systems.

1 INTRODUCTION

Interactive systems are a growing reality worldwide.

People use them for different purposes, in quite

different and complex contexts, and with unforeseen

and far-reaching consequences. They are a clear

example of how technology has left the boundaries

of offices and workplaces to pervade every aspect of

people’s personal and social life. As Sellen et al.

(2009) highlight, as far as people are not just using

technology but living with it, values become a

critical issue and must be explicitly involved in the

design of interactive systems.

As design is an activity no longer confined to

specific contexts, several authors, such as Bannon

(2011) and Cockton (2005), have claimed a

rethinking of the way interactive systems are

designed. For them, it is necessary to focus on the

intention of design as a means to improve the world

by reimagining, acting, and delivering new sources

of value. Winograd (1997) had already asserted that

the design role “goes beyond the construction of an

interface to encompass all the interspace in which

people live”, requiring a shift from seeing the

machinery to seeing the lives of the people using it.

According to the author, there is a complex interplay

among technology, individual psychology and social

communication, in a way it demands attention to

relevant factors that become hard to quantify and

even identify.

Knobel and Bowker (2011) point out that

conversations and analysis of values in technology

usually occur after design and launch. Consequently,

most users are faced with design decisions that are

undecipherable to them, that do not reflect a respect

and understanding to their way of life, their

behavioral patterns and values. For the authors, the

issue of values often arises in information

technologies as disaster needing management.

Designers necessarily communicate values

through the technology they produce (Friedman,

1996). In the context of interactive systems,

depending on the way the system is designed it will

afford behaviors that are intrinsically related to

individuals and the complex context in which they

are using it (Pereira et al., 2011). Individuals will

interpret and behave over/through the system

influenced by their cultural systems (e.g., values,

beliefs, behavior patterns). In this sense, as

Friedman (1996) highlights, although the negligence

to values in any organization is disturbing, it is

particularly damaging in the design of computer

technology, because, unlike the situation where

people can disagree and negotiate with each other

about values and their meanings, they can hardly do

the same with technology. Therefore, understanding

the role of human values in technology design is a

key factor to the development of technologies that

make sense to people and do not produce side effects

that harm them.

25

Pereira R., B. Buchdid S. and C. Baranauskas M..

Keeping Values in Mind - Artifacts for a Value-oriented and Culturally Informed Design.

DOI: 10.5220/0003996800250034

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2012), pages 25-34

ISBN: 978-989-8565-12-9

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Miller et al. (2007) and Sellen et al. (2009) point

out values as the critical issue when designing

technologies for the digital age. Some authors have

explicitly addressed issues on values in technology

design. Cockton (2005) proposes a framework to

support a Value-Centred Design, suggesting

activities and artifacts to support designers in an

understanding of technology design as a process of

delivering value. Adopting a different perspective,

Friedman (1996) has been working on an approach

she named Value-Sensitive Design, to support

concerns regarding values, especially the ethical

ones, in the design of software systems.

Other authors have investigated the influences

and impacts of cultural factors in technology design

(Del Gado and Nielsen, 1996; Marcus, 2001) and

other have argued for studies, methods, artifacts and

examples for supporting designers to deal with the

complexity and different requirements that current

technologies demand (Harrison et al., 2007; Miller et

al., 2007). Although the previously cited works have

shed light on this subject, there is a gap between

discussions about values in technology design and

practical solutions for supporting designers in this

task. Additionally, despite the acceptance of the

cultural nature of values, values and culture are

frequently approached as independent issues in

technology design. To our knowledge, no informed

approach or method is explicitly concerned with

supporting the understanding and involvement of

both values and their cultural nature in the design of

interactive systems.

In this work, we draw on Organizational

Semiotics (SO) theory (Liu, 2000) and the Building

Blocks of Culture (Hall, 1959) to create two artifacts

for supporting designers in a value-oriented and

culturally aware design of interactive systems. The

first artifact, named Value Identification Frame

(VIF), supports designers to reason about and list the

values related to the different stakeholders that may

be direct or indirectly interested and/or affected by

the system being designed. The second one, named

Culturally Aware Requirements Framework

(CARF), organizes the identification of requirements

related to cultural aspects that may impact on

stakeholders’ values. The artifacts were conceived to

facilitate their use by professionals that are not

familiar with social sciences, and were experienced

by 34 prospective designers in the context of seven

different projects of social applications for the

Brazilian Interactive Digital Television (iDTV). In

this paper we present the artifacts, the theories

underlying them, and discuss the results obtained

from their usage in the practical context.

2 THEORETICAL AND

METHODOLOGICAL

FOUNDATION

Friedman et al. (2006) understand values as

something that is important to a person or group of

people, and Schwartz (2005) as desirable, trans-

situational goals that vary in importance and that

serve as principles that guide people’s lives. For

Schwartz, values are motivational constructs that

transcend specific situations and actions, serving as

standards or criteria to guide the selection of actions,

policies, people and events.

Values are bound to culture (Hall, 1959;

Schwartz, 2005) in so subtle ways that people realize

they exist usually when rules that impact on them

are broken or violated. In many different ways,

culture influences on what people pay attention to

and what they ignore, what they value and what they

do not, the way they behave and the way they

interpret other’s behavior. The natural act of

thinking is strongly modified by culture (Hall,

1977). In this sense, if we are to approach values in

interactive systems design, we must pay attention to

their cultural nature and complexity.

When talking about culture, Hall (1977) believes

it is more important to look at the way things are put

together than at theories. Hall (1959) introduces the

notions of informal, formal and technical levels in

which humans operate and understand the world,

and approaches culture as a form of communication

giving emphasis to the nonverbal. In the OS theory

(Liu, 2000), the informal, formal and technical

levels are structured in a scheme named “Semiotic

Onion” that represents the idea that any technical

artifact is embedded in a formal system, which in

turn, exists in the context of an informal one. The

OS considers an organization and its information

system as a social system in which human behaviors

are organized by a system of norms. For Stamper et

al. (2000), these norms govern how members, think,

behave, make judgments and perceive the world,

being directly influenced by culture and values.

Aiming to formalize and structure the

characterization, analysis and comparison between

different cultures, Hall (1959) proposes 10 Primary

Messages Systems (PMS), or areas, named the basic

building blocks of culture — see Table 1. According

to the author, all cultures develop values with regard

to the 10 areas. For instance, values in “Defense” are

related to the rules, strategies and mechanisms

developed in order to protect the space (physical,

personal), the objects used to guarantee protection,

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

26

the kind of medical therapy adopted/preferred, etc.

Table 1: Hall’s (1959) building blocks of culture.

PMS

DESCRIPTION

Interaction

Everything people do involves interaction with

something/someone else: people, systems, objects, animals,

etc. The interaction is at the centre of the universe of

culture and everything grows from it.

Association

All living things organize their life in some pattern of

association. This area refers to the different ways that

society and its components are organized and structured.

Governmental and social structures may vary strongly

according to the culture.

Learning

Learning is one of the basic activities present since the

beginning of life. Education and educational systems are

strongly tied to emotion and as characteristic of a culture as

its language.

Play

Funny and pleasure are terms related to this area. Although

its role in the evolution of species is not well understood

yet, “Play” is clearly linked to the other areas: in learning it

is considered a catalyst; in relationships a desirable

characteristic, etc.

Defense

Defense is a specialized activity of vital importance.

People must defend themselves not only against hostile

forces in nature, but also against those within human

society and internal forces. Cultures have different

mechanisms and strategies of protection.

Exploitation

It is related to the use of materials in order to explore the

world. Materials in an environment are strongly related to

the other aspects of a culture. It is impossible to think

about a culture with no language and no materials.

Temporality

Time is related to life in several ways: from cycles, periods

and rhythms (e.g., breath rate, heartbeat) to measures (e.g.,

hours, days) and other aspects in society (e.g., division

according to age groups, mealtime). The way people deal

with time and the role of time in society varies across

cultures.

Territoriality

It refers to the possession, use and defence of space.

Having a territory is essential to life; the lack of a territory

is one of the most precarious conditions of life. There are

p

hysical (e.g., country, house) as well as social (e.g., social

p

osi

t

ion, hierarchy) and personal spaces (e.g., personal

data, office desk).

Bisexuality

It is related to the differences in terms of form and function

related to gender. Cultures have different forms of

distinction and classification and give different importance

to each one.

Subsistence

This area includes from people’s food habits to the

economy of a country. Professions, supply chains, deals,

natural resources, are all aspects developed in this area and

that vary strongly according to the culture, being

influenced not only by the other areas but also by

geographical and climatic conditions.

Values may also be developed in the intersection

of different areas and one may approach them in

terms of the informal, formal and technical levels.

For instance, “Privacy” may be understood as a

value developed in the intersection of “Protection”

and “Territoriality” areas. People from different

cultures tend to have their own informal

understanding of what privacy is and what it means.

There are social protocols, conventions, rules and

laws that are formally established to define the

meaning, limits and guarantees of an individual’s

privacy and that varies according to the culture

being analyzed. There are also some facets of

privacy that are so formally accepted that can be

technically supported, such as a curtain to cover a

window, the wall for restricting the visibility of a

house and the privacy of medical examinations.

In the context of interactive systems, the way the

value of “Privacy” (or the lack of it) has being

handled and supported by applications, mainly the

so-called Social Software, has been the cause of

several problems widely reported in the Web.

Winter (2010) draws attention to how Facebook

®

has become a worldwide photo identification

database and highlights that privacy issues go from

what the application does with users’ data to what it

allows other applications to do. In the complex

scenario of designing interactive systems for wide

audiences, designers have to show an understanding

of the different ways people value and manage their

privacy, and also to comply with the laws

established in the social environment these people

live. Otherwise, the produced system may trigger

undesired side-effects both in the environment it is

introduced and on the people living in it.

The OS theory (Liu, 2000) provides methods

(e.g., Problem Articulation Method, Norm Analysis

Method) and artifacts (e.g., Semiotic Ladder,

Ontology Charts) that support designers in

considering the social world and its complexity from

the articulation of problems stage to the modeling of

computer systems. The Stakeholders Identification

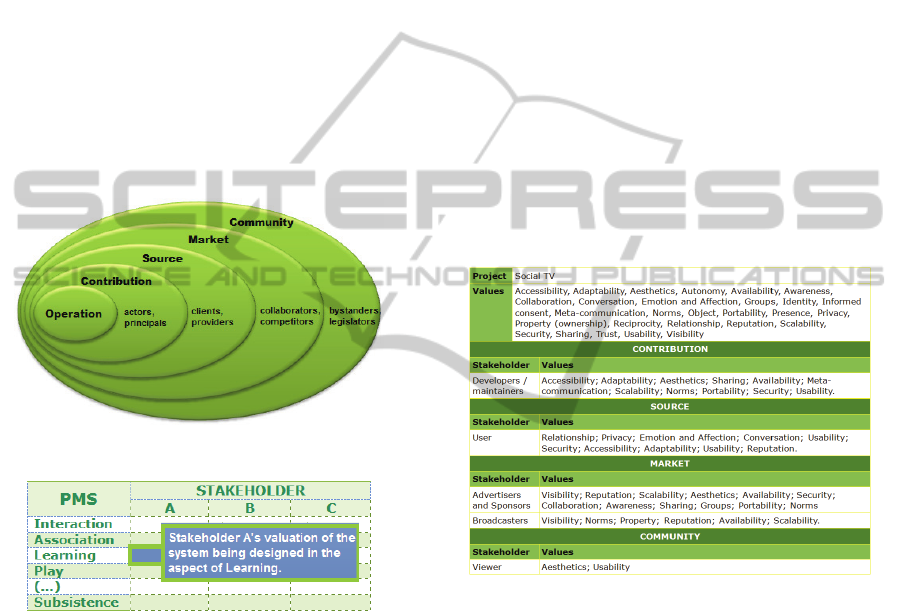

Diagram (SID) is an artifact from OS — see Figure

1, that supports the identification of all the

stakeholders direct or indirectly affected by the

system being designed. The artifact distributes

stakeholders into different categories: from the

actors directly involved in the project to the people

who may not use the system but may be affected by

it. The SID considers that each group of stakeholder

brings different perspectives to the innovation being

designed, having its own cultural system that

governs the way it will see, understand, value and

react to the proposed innovation (Kolkman, 1993).

KeepingValuesinMind-ArtifactsforaValue-orientedandCulturallyInformedDesign

27

Understanding the way different stakeholders

would value and react to an innovation requires

designers to see the world through the lenses of

these different stakeholders. The Valuation Framing

(VF) is another artifact from OS (Liu, 2000) that

helps in carrying out this kind of analysis by

favoring the analysis of the cultural dimensions of a

product — see Figure 2.

The VF is built on Hall’s (1959) areas of culture

with a few adjustments. For instance, “Defense” was

renamed to “Protection” and “Bisexuality” to

“Classification” (Kolkman, 1993) in order to

encompass, beyond the notion of gender, issues of

age, instructional, social and economical levels. In

the artifact, the analyst’s work consists of

questioning, predicting and hypothesizing how the

innovation may affect/is affecting the different

groups of stakeholders regarding the 10 areas.

Figure 1: SID artifact. Adapted from (Kolkman, 1993).

Figure 2: Valuation framing. Adapted from (Liu, 2000).

3 TWO NEW ARTIFACTS

As Sellen et al. (2009) suggest, the curricula in

Computer Science do not traditionally direct much

effort in enabling its students to cope with social

issues. It stresses as important the work with

multidisciplinary teams that can contribute with

different visions to a project. Multidisciplinary

teams, however, are not always possible or viable

due to project’s scope, restrictions and limitations.

Consequently, as Miller et al. (2007) highlight, if

designers working in industrial settings are to

account for values, we have to provide them light-

weight and principled methods to do so.

We have used artifacts from OS and techniques

inspired on Participatory Design (Schuler and

Namioka, 1993) to support design activities in

different contexts (Pereira and Baranauskas, 2011).

However, dealing with values is not a trivial activity,

and designers need practical artifacts to help them to

think of values in an explicit way and to identify the

project’s requirements related to these values.

Following, we present the VIF and CARF artifacts,

both created on the grounds of OS theory (Liu,

2000) and Hall’s (1959) building blocks of culture

— the artifacts’ templates can be downloaded at

www.nied.unicamp.br/ecoweb/products/artifacts.

The VIF artifact was created to support the

identification of the values related to the different

stakeholders that may be direct or indirectly

interested and/or affected by the system being

designed — see Figure 3. Its input is the list of

stakeholders identified through the SID artifact; and

its output is a list of the values each different

stakeholder brings to the project.

Figure 3: Value identification frame.

The basic principles of the artifact are: each

stakeholder has a set of values that may cause/suffer

impact with the introduction of the innovation being

designed. The analyst’s work is to map what values

each stakeholder brings to the project and have to be

considered in the design.

The artifact is inspired on the SID — illustrated

by Figure 1. Its header has a space in which

designers can put the name of the project —

corresponding to the SID’s core layer, and a list of

values to serve as a start point for the activity. The

VIF has also four blocks related to the other layers

of SID: “Contribution”, “Source”, “Market” and

“Community”. Each block has two columns: in the

first one, designers put the stakeholders identified in

the respective layer; in the second one, they indicate

what values the stakeholder is bringing to the project

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

28

and must be taken into account. Because the SID

induces designers to think of all the stakeholders

direct/indirectly involved in the system being

designed, by preserving its structure, the VIF leads

designers to think of the values of all the different

stakeholders making them explicit.

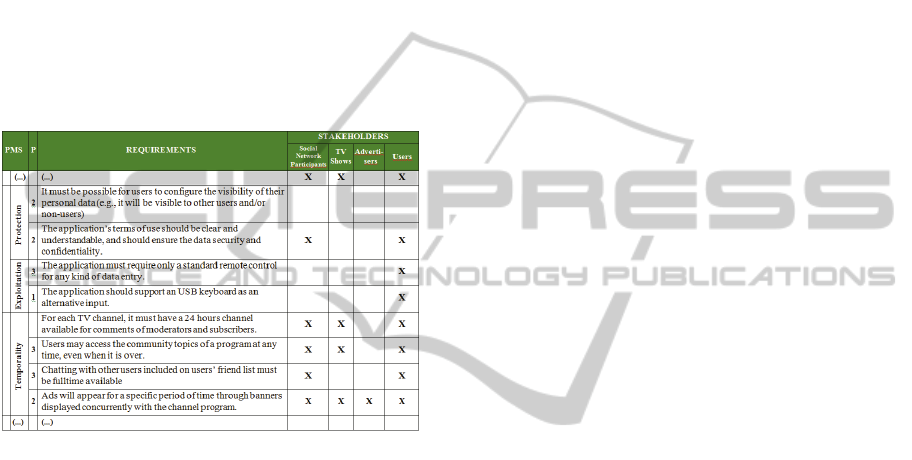

The CARF artifact was created to support the

identification and organization of requirements that

are related to cultural aspects of the different

stakeholders and their values — see Figure 4. Its

inputs are: the 10 areas of culture; the stakeholders

identified through the SID; and the values mapped

for each stakeholder through the VIF. The output is

a ranked list of requirements that are related to the

stakeholders and their values.

Figure 4: Culturally aware requirements framework.

The basic principles of the artifact are: values are

culturally developed according to the Hall’s 10 areas

of culture. Depending on the way the innovation is

designed it will impact on different aspects of these

areas, promoting/inhibiting the values of different

stakeholders. The analyst’s work consists of: i)

identifying requirements for the project according to

the 10 areas in order to respect the values of the

stakeholders, ii) defining priorities among these

requirements and iii) dealing with possible conflicts.

The artifact is inspired on the VF — illustrated

by Figure 2. The column “PMS” presents the Hall’s

10 areas; the column “P” indicates the priority of

each requirement specified (“3”–High, “2”–

Average; “1”–Low); the column “Requirements”

describes the requirements related to each area of

culture that may impact on stakeholders’ values; and

the column “Stakeholder” indicates the stakeholders

whose values may be positively/negatively affected

by the requirement.

In practical terms, the stakeholders identified

through the SID are inserted into the artifact, and

designers have to reason, make questions and try to

identify, in each area, the requirements that are

related to the values of these stakeholders. Finally,

they mark an “X” in the column of each stakeholder

that may be affected by the requirement and assign a

priority to the requirement (from 1 to 3).

4 THE CASE STUDY

In 2003, the Brazilian government instituted the

iDTV intending to promote: i) the formation of a

national network for distance learning; ii) the access

of people to knowledge by reducing economic,

geographical and social barriers; iii) the research and

development; and iv) the national industry (Brasil,

2003). In this context, values of different

stakeholders may suffer and cause influence on the

applications, the way they are used, and the impact

they may trigger on the society. The government,

private organizations, the media etc., have different

interests and perspectives regarding the introduction

of iDTV in the country. The contents broadcasted,

the interaction possibilities, the applications’

interface, and even the devices needed for receiving

the digital signal and interacting with the iDTV,

communicate some of those interests. Brazil is the

fifth largest country in territory and population,

having a very heterogeneous population in terms of

ethnicity, social and economical conditions, and the

analogical television is present in more than 97% of

Brazilian homes (IBGE, 2010). Consequently, it

becomes critical to think of values and culture when

designing applications for the iDTV in order to not

deliver applications that trigger undesired side-

effects on the society. In this section we present a

practical activity in which the VIF and CARF were

used in the design of applications for the iDTV.

The case study was conducted in a Computer

Science undergraduate discipline for “Construction

of Human-Computer Interfaces”, in which the

Problem Articulation Method from OS (Liu, 2000)

was used as an approach for the design of

information systems. A total of 34 participants were

divided into 7 groups: G1 (formed by the

prospective designers: D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5), G2

(D6..D10), G3 (D11..D14), G4 (D15..D19), G5

(D20..D24), G6 (D25..D29) and G7 (D30..D34).

The theme proposed to the participants was “social

applications for the iDTV”. The course took place

from August to December, 2011, and by its end each

group had to present a functional prototype of its

project and socialize the final results with the other

groups.

KeepingValuesinMind-ArtifactsforaValue-orientedandCulturallyInformedDesign

29

From the 7 projects: G1 and G5 are applications

intended to promote sustainable behavior on their

users. G2 is an application to support social

interaction on football matches programs. G3 and

G4 are related to social networks for the iDTV. G6

is an application to support online chat and G7 is

related to interactive online courses through the

iDTV — see Figure 5 for some examples. After the

course was finished, the groups were asked to

voluntarily answer an online questionnaire in order

to evaluate the activity and it was requested their

permission for using all the material they produced

in the course, including their answers to the

questionnaire. Another group of 4 participants (G8)

opted for not answering the questionnaire and is not

being included in this analysis.

The activity was divided into two parts. In the

first part, the groups used the VIF to make it explicit

the values each stakeholder was bringing to the

project. In the second part, the groups used the

CARF to identify what requirements they should pay

attention to in order to develop systems that make

sense to users and do not cause negative effects on

them. When the activity started, each group had

defined the focus of its project, had identified the

stakeholders using the SID, and discussed the

possible problems, solutions and ideas related to

each stakeholder using the Evaluation Frame (EF)

(Baranauskas et al., 2005)— another artifact inspired

on OS, which organizes the stakeholders according

to the SID’s structure and invites designers to reason

about the problems and solutions related to each one.

The main steps when using the VIF artifact were:

1. Participants selected the most representative

stakeholders identified through the SID and inserted

them into the VIF’s corresponding block. 2. For

each stakeholder, participants discussed what values

it would bring to the project; what would be

important to it and how the system being designed

would (should) impact on its values. In order to give

participants a starting point, it was suggested 28

values in the context of systems for promoting social

interaction (Pereira et al., 2010). As a result, each

group had a map showing the different stakeholders

and their values — Figure 3 illustrates the

VIF filled

by G3, translations were made by the authors.

The main steps when using the CARF artifact

were: 1. Participants selected at least one

stakeholder from each SID’ layer, inserting them as

a new column into the CARF’s “Stakeholder”

section. 2. For each area (PMS), they should identify

requirements (resources, norms, quality attributes,

functionalities, etc.) that should be considered in the

system in order to support the stakeholders’ values.

3. Participants should mark an “X” in the column of

each stakeholder whose values would be promoted/

inhibited by the requirement. 4. After filling the

artifact, participants should rank the requirements

according to their importance to the project.

As a result, each group had a list of requirements

related to cultural aspects and values of its

stakeholders, a map of the possible impact of these

requirements on different stakeholders and an

indication of priority for each requirement — Figure

4 illustrates the CARF filled by G7, translations

were made by the authors.

As background material for supporting the

activity each group was supplied with: i) guidelines

explaining the activity’s steps; ii) the VIF and CARF

artifacts both in press and digital format; iii) a table

containing the list of 28 values in the context of

social applications (Pereira et al., 2010); iv) a

simplified explanation of each area of culture — as

in Table 1; and v) at least 3 questions related to each

area the groups should think about — see Table 2.

The letters into the brackets in Table 2 indicate the

stakeholders directly related to each question: [D]

Designer, [G] Government, [S] TV Station, [T]

Figure 5: Prototypes from G1, G5 and G6.

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

30

Transmission Industry, [U] User.

Table 2: Questions in each area for the iDTV context.

PMS

DESCRIPTION

Interaction

What interaction possibilities will the application offer? [D];

What kinds of actions can users perform? With what\who?

Why? Through which devices? [U, T]; How do people

interact with the analogical TV? What will be changed? [G,

S, T, U]

Association

Is the application usage individual or collective? [U]; Is

there any dependence on other organizations/ entities (e.g.,

data supply)? [S]; May it cause impact on any aspect o

f

collective life? [G, U]; Is it associated with television

content? [S]

Learning

Is it required any prior knowledge for learning how to use

the application? What is the cognitive effort for learning it?

What kind of learning it can provide? [U]; It is required

training, new abilities or tools for developing the

application? Which ones? [D]

Play

What kind of emotions the application may/should evoke

/avoid (e.g., fun, challenge, warning)? Why? [D, G, S, U];

How the application has to be designed to promote/inhibi

t

these emotions? [D]; What are the possible impacts on

users? [U]

Defense

Can the application compromise users’ safety? [U]; What

are its policy and terms of use? [D, G, S, U]; Is there any

rights, patent or property? [G, S, T]

Exploitation

What are the physical devices required to interact

with/through the application? [D, T]; Is it required any othe

r

material or modification in the environment (e.g., sound,

media)? [D, U]; Will the introduction of new devices

generate the disposal of old ones? Is there any way to reuse?

[D, G, S, U]

Temporality

Is there a formal period for interacting (morning, lunch)? [D

, G, T]; What is the expected frequency of use (daily,

monthly)? [U]; What about the interaction duration? Is it

brief, medium or long? [D]

Territoriality

In which space the application will be used? [U]; Are there

specific requirements for the interaction space (size,

lighting, sound)? What kind of impact may

b

e generated?

[D, U]; Is the usage individual or collaborative? [D, S]

Bisexuality

Are the technologies necessary to develop the application

open source? [D]; Is its final cost (including the physical

devices) viable/accessible for the different socio-economic

conditions of users? [U, G, S]; May it cause negative impact

on economic issues? How? [U]

Subsistence

What is the target audience? [U]; Is it required minimum

age to participate? [A, G, U, S]; Is it required information

redundancy (the same information in different formats)? [D,

G, S, U]

The material produced in this activity was used

to support groups in the forthcoming steps of

their projects. 1. With the list of values and

requirements at hands, each group produced the first

version of its system’s prototype — an adapted

version of the Brain Drawing technique (Schuler and

Namioka, 1993) was conducted and the iDTV

design patterns from Kunert (2009) were followed.

2. The Balsamiq

®

tool was used to draw the users’

interfaces and the CogTool

®

was used to create the

interactive prototypes.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on the material produced in the case study,

including the final prototypes created by the groups,

it was possible to identify the VIF and CARF as

promising artifacts for supporting designers in a

value-oriented and culturally aware design. Both the

artifacts met the needs that led to their conception: i)

thinking of values in an explicit way and ii)

identifying the requirements related to these values.

As an illustration, Figure 6 shows the prototype

produced by G3 regarding a social application for

the iDTV. Through the VIF, the group made explicit

the values of the stakeholders involved in the

project. For instance, the group pointed out

“Privacy”, “Accessibility”, and “Relationship” as

values of the stakeholder “users”. Through the

CARF, the group discussed about the project

according to each area of culture, and specified

requirements that should be considered in order to

account for the values.

For promoting the value of “Privacy”, in CARF’s

“Protection” area, the group specified that: 1. “Users

have to agree explicitly for letting their profile

publicly visible”. 2. “The application must be

included in the ‘Parent’s Control’ functionality,

protected by a password”. 3. “The application must

allow users to turn on/off the ‘History recording’

feature”. The detail (1) in Figure 6 represents the

configuration feature that allows users to choose: i)

whether their activity history will be recorded; ii)

whether other users are allowed to see their updates;

and iii) whether they want to receive

recommendations from other users.

For promoting the value of “Accessibility”, in

CARF’s “Exploitation” area, participants specified

that the application must have: 1. “The possibility of

changing the size of interface elements and the color

contrast”. 2. “Subtitles for spoken communication”.

3. “A help section and additional information about

the features”. The detail (2) in Figure 6 indicates the

possibility of changing the size of the interface

KeepingValuesinMind-ArtifactsforaValue-orientedandCulturallyInformedDesign

31

elements and the detail (4) indicates a “Help” feature

— it is related to the “Learning” area. Understanding

the “Exploitation” and “Learning” areas of culture is

key to design an accessible solution in the proposed

scenario because, as Neris et al. (2007) argue,

designers need to know users in their abilities,

preferences, and motor and cognitive limitations,

formalizing the interaction requirements and

investigating solutions of interaction and interface

for the diversity. This is very different from

developing applications for the “average user” that

would not capture the reality of a plural context such

as the Brazilian one.

Figure 6: Prototype designed by G3.

For promoting the value of “Relationship”, in

CARF’s “Association” and “Interaction” areas the

participants specified that: 1. “It must be possible for

users to interact with each other through chat and

messages”. 2. “The application should recommend

‘friends’ to users according to the information of

their profile”. 3. “It must be possible for users

creating their lists of friends, family members, other

groups, etc.”. The detail (3) in Figure 6 indicates the

feature for managing “friends”. Furthermore, we can

point out another example: through the VIF, the G3

identified the value of “visibility” for the stakeholder

“Sponsorship”. In CARF’s area of “Subsistence”,

G3 adopted the strategy of providing ads services for

funding the maintenance costs: “The profit will be

generated through ads from sponsors and the TV

programs”. The detail (5) in Figure 6 indicates a

banner where ads are displayed.

Values of other stakeholders and their related

requirements were also considered by G3. For

instance, “Reputation” is a value of the stakeholder

“TV Station” and is related to the area of

“Classification”. The group specified requirements

and designed a feature in which users can rate

programs, add them to their favorite list, and share

the list with their friends. The same was identified

on the projects of other groups. For instance, before

using the artifact, G1 (designing a game for

sustainable behavior) was not paying attention to the

value of “Identity” of its stakeholder “user”. When

discussing the area of “Classification”, participants

perceived that their initial ideas would lead to a

biased design in which users would have to use the

avatar of a little boy — no possible changes were

possible. After filling the artifacts, they designed a

feature where users could choose between a little

boy and a girl avatar, accounting for the differences

of gender and preferences when playing.

According to the answers in the evaluation

questionnaire, identifying the values of the

stakeholders involved in the application being

designed led the groups “to evaluate the impact of

the project on each stakeholder and, then, to adapt

the project according to the stakeholders’ needs and

values” [G4]. Other group mentioned that thinking

of values “contributes to have a wider perception

and understanding of the stakeholders involved in

the project, their point of view, and the real purpose

of the application we should develop to them” [G5].

And also, that thinking of values “is of critical

importance because it helps us to see who may be

affected by the project, and what values we should

pay attention to in order not to cause negative side-

effects on any stakeholder” [G6].

Regarding the utility of VIF and CARF, groups

were asked about their perceived utility and

contribution to the project. Two groups answered

that both artifacts contribute strongly and were

determinant to the identification of the values (VIF)

and the requirements related to stakeholders’ values

and culture (CARF). Four groups answered they

contribute to the process, and a group answered they

are indifferent (neutral). None answered the artifacts

do not contribute or make the activity difficult —

see Figure 7.

Figure 7: Contribution of the artifacts to the projects.

For G2, understanding culture and values is

mandatory when designing applications for a wide

and complex context like iDTV. For G3, this

understanding favors “the identification of important

points during the design stage” preventing re-work,

additional costs with modifications and even the

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

32

project’s failure. For G4, the artifacts “contribute to

structure and organize ideas”; they “support a better

view and understanding of the project”, and they

“contribute to the development of the application

taking into account the points that are truly

important in the users’ context”.

When asked about the positive aspects of both

artifacts, G1 answered they “provide a wide

perception (what is needed and why), and a basis for

reasoning about the project”. G2 cited the artifacts

contribute to “structure, organize and better

understand the ideas for the project”. G4 pointed out

that the artifacts are “simple and easy to understand”

and that they “direct the project toward the

consideration of values”. And G6 answered that the

artifacts contribute to “manage and develop the

project, respecting the values of each stakeholder

and finding new requirements to the project”. On the

other hand, when asked about the negative aspects,

G4 asserted that the artifacts “need additional

information for supporting their usage”. G7 cited

the high quantity of terms and aspects to be

considered. And G2 suggested that the “areas of

culture in CARF could be more explained” and that

the artifacts have “too many variables, making it

difficult to keep the simplicity and to think of only a

few stakeholders and their values”.

These aspects suggest that the artifacts must be

as simple as possible in order to not overload

designers with complex terms and unnecessary

steps. However, as the authors we cited previously

have argued, dealing with values and culture in

technology design is a great challenge we are facing

in the present. In part, it is due to the topic’s inherent

complexity, and that becomes even more difficult

due to the lack of training and familiarity with social

subjects students in technological areas have.

Therefore, some initial difficulty in learning how to

use the artifacts is expected.

Indeed, our main concern when creating the

artifacts was to find a balance between making them

self-explanatory and informative, while keeping

them as simple and easy to use as possible. For

instance, during the case study we identified that it

would be useful to include a column named “Value”

in the CARF in order to make explicit the

relationship among the requirements, the areas of

culture and the stakeholders’ values. Additionally,

the values included in the VIF artifact (see Figure 3)

have been used in different contexts (Pereira and

Baranauskas; Pereira et al., 2011) and seems to be a

good starting point for the discussion on values in

applications intended to promote social interaction.

In the evaluation questionnaire, groups were asked

whether the values contributed to the activity. Two

groups (28%) answered they were indifferent, while

5 groups (72%) answered they contributed or

contributed strongly to the activity.

For the CARF artifact, groups were asked

whether the description of each area of culture, and

the questions related to it, contributed to the

clarification of requirements related to stakeholders’

cultural aspects that could impact on their values.

The 7 groups (100%) answered positively (the

artifact contributed), and highlighted that the CARF

“is comprehensive, and the questions make it self-

explanatory” [G1]; “give a direction in the

requirements identification activity” [G3], and “it is

a well-synthesized structure to support seeing and

understanding culture during the development stage;

they make you reason on all the aspects that can

influence in the project development” [G4].

Regarding all the artifacts used in the case study,

the 7 groups (100%) answered they would use the

artifacts to support their activities in other contexts,

mainly when designing a new product to be used by

a wide audience. The SID and CARF were cited by

the 7 groups (100%); while 6 groups cited the VIF

(86%) and 5 groups cited the EF (72%).

In sum, although further exposition of the

artifacts to other students and professional designers

in different contexts is still needed, the results

obtained from the case study as well as the answers

to the evaluation questionnaire indicate both VIF

and CARF as promising artifacts for supporting

designers in the complex scenario of designing

value-oriented and culturally aware solutions.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Designing technologies that understand and respect

human values is an ethical responsibility, a need and

a challenge for all those who are direct or indirectly

involved with design. However, although clearly

recognized as important, there are few initiatives in

literature relating culture and values to technology

design. There is also a lack of approaches, methods

and artifacts for supporting designers in dealing with

values and cultural aspects in practical contexts. In

this paper we shed light on this scenario proposing

the VIF and CARF artifacts and suggesting other

existing artifacts (e.g., SID, VF, EF) that may

support designers in practical settings.

The artifacts were used by 34 prospective

designers in a case study related to the design of

applications for the Brazilian Interactive Digital

Television. The results obtained from this case study

KeepingValuesinMind-ArtifactsforaValue-orientedandCulturallyInformedDesign

33

indicate the benefits of using the artifacts for

supporting designers in keeping values in mind

during the design activities and in identifying

requirements related to the cultural aspects of

stakeholders that may impact on their values. The

case study also suggested some points that could be

improved in the artifacts and that may be subject of

further studies.

Finally, although the artifacts have shown

interesting results, they alone are not enough to

guarantee an effective consideration of values and

culture in interactive systems design. Indeed, as the

experiment presented in this paper has shown, other

artifacts, methods and tools are needed in order to

allow the articulation and involvement of values and

other cultural aspects during the different stages of a

system design. We are naming value-oriented and

culturally informed approach (VCIA) such set of

artifacts and methods we are investigating in

ongoing and further research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is partially funded by CNPq through

the EcoWeb Project (#560044/2010-0) and FAPESP

(#2009/11888-7). The authors specially thank the

participants of the case study who voluntarily

collaborated and authorized the use of the

documentation of their projects in this paper.

REFERENCES

Bannon, L. 2011. Reimagining HCI: Toward a More

Human-Centered Perspective. Interactions. 18(4).

p.50-57.

Baranauskas, M. C. C., Schimiguel, J., Simoni, C. A. C.,

Medeiros, C. M. B. 2005. Guiding the Process of

Requirements Elicitation with a Semiotic Approach. In

11

th

International Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction. Las Vegas. Lawrence Erlbaum p.100-111.

Brasil, Presidential Decree No 4.901. 2003. retrieved from

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/2003/d4

901.htm, on Jan 20, 2012.

Cockton, G. 2005. A Development Framework for Value-

Centred Design, in ACM CHI 2005. p.1292-1295.

Del Gado, E. and Nielsen, J. 1996. International Users

Interface. New York: John Wiley.

Friedman, B. 1996. Value-Sensitive Design. Interactions.

3(6). p.16-23.

Friedman, B., Kahn, P. H. and Borning, A. 2006. Value

sensitive design and information systems, In Human-

Computer Interaction and Management Information

Systems: Foundations. Armonk. p.348-372.

Hall, E. T. 1959. The Silent Language. Anchoor Books.

Hall, E. T. 1977. Beyond Culture. Anchor Books.

Harrison, S., Tatar, D., Sengers, P. 2007. The three

paradigms of HCI. in AltCHI – CHI'07. p.1-21.

IBGE. National Survey by Household Sample. 2010.

Retrieved from: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/

download/estatistica.shtm, on Jan 20, 2012.

Knobel, K. and Bowker, G. C. 2011. Values in Design,

Communications of the ACM. 54(7). p.26-28.

Kolkman M. 1993. Problem articulation methodology.

PhD thesis. University of Twente, Enschede.

Kunert, T. 2009. User-Centered Interaction Design

Patterns for Interactive Digital Television

Applications. Springer.

Liu, K. 2000. Semiotics in Information Systems

Engineering. Cambridge University Press.

Marcus, A. 2001. International and Intercultural user

interfaces. In Users Interfaces for All: Concepts,

Methods and Tools. Lawrence Erlbaum. p.47-63.

Miller, J., Friedman, B., Jancke, G. and Gill, B. 2007.

Values Tensions in Design: The Value Sensitive

Design, Development, and Appropriation of a

Corporation’s Groupware System. In ACM

GROUP’07. p.281-209.

Neris, V. P. A. and Baranauskas, M. C. C. 2007. End-user

Tailoring: a Semiotic-informed Perspective. In ICOS’

2007 International Conference on Organizational

Semiotics. p.47-53.

Pereira, R., Baranauskas, M. C. C. and Silva, S. R. P.

2010. Softwares Sociais: Uma Visao Orientada a

Valores. In IX Brazilian Symposium on Human

Factors in Computer Systems ( IHC’10). p.149-158.

Pereira, R., Baranauskas, M. C. C. and Almeida, L. D.

2011. The Value of Value Identification in Web

Applications. In IADIS International Conference on

WWW/Internet (ICWI). p.37-44.

Pereira, R. and Baranauskas, M. C. C. 2011. Valuation

framing for social software: A Culturally Aware

Artifact,

In 13th International Conference on

Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS), p. 135-144.

Schuler, D. and Namioka, A. 1993. Participatory design:

principles and practices. Hillsdale. Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Schwartz, S. H. 2005. Basic human values: Their content

and structure across countries. in Values and

Behaviors in Organizations. Vozes. p.21-55.

Sellen, A. Rogers, Y. Harper, R. and Rodden, T. 2009.

Reflecting Human Values in the Digital Age,

Communications of the ACM. 52(3). p.58-66.

Stamper, R., Liu, K., Hafkamp, M. and Ades, Y. 2000.

Understanding the Role of Signs and Norms in

Organisations – a semiotic approach to information

systems design. Journal of Behaviour and Information

Technology. 19(1). p.15-27.

Winograd, T. 1997. The design of interaction. In Beyond

Calculation: The Next Fifty Years of Computing.

Copernicus. Springer-Verlag. p.149-161.

Winter, J. 2010. Pedophiles Find a Home on Wikipedia.

Fox News. Retrieved from: http://www.foxnews.com/

scitech/2010/06/25/exclusive-pedophiles-find-home-

on-wikipedia/, on Jan 20, 2012.

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

34