Managing Literature Reviews Information through Visualization

Sandra Fabbri

1

, Elis Hernandes

1

, Andre Di Thommazo

1,2

, Anderson Belgamo

1,3

,

Augusto Zamboni

1

and Cleiton Silva

2

1

Software Engineering Research Lab, Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, Brazil

2

Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo, São Carlos, SP, Brazil

3

Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de São Paulo, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil

Keywords: Systematic Literature Review, Systematic Mapping, Tool, Visualization.

Abstract: Systematic Literature Review (SR) and Systematic Mappings (SM) are scientific literature review

techniques that follow well-defined stages, according to a protocol previously elaborated. The goal is

helping in finding evidence about a particular research topic and mapping a research area, respectively.

Their steps are laborious and a computational support is essential to improve the quality of their conduction.

Aiming to offer computational support to these types of reviews, the StArt (State of the Art through

Systematic Review) tool was developed. Besides the expected functionalities, StArt generates studies score,

uses information visualization and text mining techniques to facilitate the research area mapping and to

identify the studies relevance. StArt has been developed through an incremental process by academics who

adopt SR and SM. As the expectation is to have a tool that really aids the conduction of these types of

reviews, new ideas are always investigated and make StArt different from other alternatives. Visualization

and text mining techniques seems to be a powerful resource for facilitating data abstraction in the context of

SRs and SMs, allowing the improvement of the review and the conclusions about it.

1 INTRODUCTION

The Systematic Literature Review process (SR or

SM) has its origins in the medical area and its

objective, according to Pai et al. (2004), is the

creation of a complete and impartial summary about

a given research topic following well defined and

known procedures. Recently, this process is being

adapted to the computer science area, particularly in

Software Engineering (Kitchenahm, 2004). Some

advantages of the SR usage are the coverage, the

replicability and the reliability of its process.

Besides systematizing the search for relevant

studies, the SR predicts the organization and the

analysis of the obtained results. However, the SR

process is more laborious than the research

conducted on an informal basis (Kitchenahm, 2004).

A previous activity to the SR should can be the

Systematic Mapping (SM) which objective,

according to Petersen et al. (2008), is to build a

classification scheme and to structure a software

engineering research area. Like a SR, SM is also a

laborious activity and its process is similar to the SR

process, with many repetitive steps. One of the main

differences between SR and SM is that the desired

results of SMs are mainly quantitative but not

qualitative and the studies should not be read in full.

Despite this fact, quantitative data can also aid the

summarization that should be provided by a SR.

Thus, considering that there are several steps to

be executed and several documents to be managed,

the computer support can aid the conformance to the

SR and SM processes, enabling higher quality in

their execution.

Since 2006 the Start tool (Montebelo et al, 2007)

has been developed. In 2008 it was completely

restructured and the new version was available

(Zamboni et al., 2010) (Hernandes et al., 2010). This

version gave full support to carry out SRs and

currently, visualization and text mining resources are

being added for easing data summarization since, in

general, there is a lot of data for transforming into

knowledge, which is a challenge. As mentioned by

Burley (2010), information visualization is a

valuable tool for knowledge integration activities

and, in StArt, such views allow the researcher to

find, in a simple way, information on the most

important events, the evolution of the research topic

by the academic community, and so on. This

36

Fabbri S., Hernandes E., Di Thommazo A., Belgamo A., Zamboni A. and Silva C..

Managing Literature Reviews Information through Visualization.

DOI: 10.5220/0004004000360045

In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2012), pages 36-45

ISBN: 978-989-8565-11-2

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

information is very common in SM.

Another important contribution that has been

reached with information visualization in StArt is

the evaluation of the search strings quality. An

important point in this kind of literature reviews is to

find and ensure that the search strings bring all the

relevant studies on the research topic. The Start tool

provides a visualization of all the studies retrieved as

well as their references. Hence, it is possible

identifying for example, if a frequently cited

reference was or was not retrieved by the search

string.

Based on this context, the objective of this paper

is to explore the contributions of information

visualization for this kinds of literature reviews.

Section 2 presents an overview of StArt

functionalities and highlights some features that aid

the control of the processes related to these kinds of

literature reviews. Section 3 explains the

visualization support provided by StArt and how it

can be used to enhance the summarization of the

investigated topic. Section 4 presents the support of

text mining processing and Section 5 presents the

conclusions and future work.

2 AN OVERVIEW OF THE StArt

Before explaining how information visualization and

text mining processing help on identifying important

information for SM and SRs, an overview of the

main functionalities of StArt is presented below. As

mentioned before, the processes of SR and SM have

some repetitive steps and require discipline and

systematic practice from the researcher. The

information must be registered in an organized way,

such that the expected results are reached, the

process can be replicable and all the information can

be packed.

Thus, StArt has been developed for providing

automated support to as many steps as possible.

Functionalities to ease data summarization were also

implemented in the tool as the possibility to display

data through visualization and Excel formatted

reports, according to the researcher’s needs.

As the SM process is a subset of the SR process,

StArt was initially planned to support SRs and

currently it is being adapted to also support SMs.

Figure 1 illustrates the general process of SR,

highlighting what is done with (left side) and

without (right side) StArt support. As electronic

scientific databases do not allow automated search

of primary studies, steps 2, 3 and 4 must be executed

without the support of the tool. They are: the

adjustment of search strings in search engines,

which happens while the protocol is being defined

and reviewed; the execution of these search strings

after the protocol approval; and the exportation of

the search result in a BibTex file, respectively. The

step numbers used in this figure will be used in the

explanation of the StArt functionalities.

The main functionalities of StArt are presented

in the screen shot of Figure 2. At the left side there is

the hierarchical directory tree with the SR process

phases. At the right side, the information associated

to the functionality selected on the left side is

presented.

Shortly, the goals of the three phases are:

Planning Phase, which consists of the protocol

filling (Step 1 of Figure 1);

Execution Phase, which is composed of Studies

Identification (Steps 2, 3, 4, and 5 of Figure 1),

Selection (Steps 6, 7, and 8 of Figure 1) and

Extraction (Step 9 of Figure 1). In this phase

the researcher should identify the studies, select

them and extract the relevant information for

answering the research question.

Summarization Phase (Steps 10 and 11 of

Figure 1), which corresponds to the analysis of

the data extracted from each accepted study and

the elaboration of a final report describing the

state of the art. For this phase, StArt provides

graphics, spreadsheets and data visualizations,

aiming to make the researcher’s tasks easier.

Such options will be detailed in Section 4.

Following, each phase is detailed, exemplifying

the support provided by the StArt tool.

2.1 Planning

In this phase StArt supports the SR Protocol

elaboration (Step 1 of Figure 1) according to the

attributes suggested by Kitchenham (2007). Some of

the attributes are: research question definition;

keywords that will be used for searching for studies;

search engines; criteria for acceptance or rejection of

studies; etc. There is a help message for each

protocol attribute aiming to guide its filling. The

protocol is stored in the tool and can be accessed and

modified if necessary. It is worth noting that, to

ensure the SR process conformance, the content of

the protocol fields are reflected in later steps of the

SR process. For example, when a search engine is

chosen during the protocol filling, it is added under

the Studies Identification of the Execution Phase, as

shown in Figure 3. Similarly, each attribute inserted

in the Information Extraction Form Attributes during

the protocol filling becomes a field that must be

ManagingLiteratureReviewsInformationthroughVisualization

37

Figure 1: SLR steps: Left side – actions supported and Right side – actions not supported by StArt.

Figure 2: Overview of the StArt tool.

filled in during the Extraction Step (Step 9 of Figure

1), as shown in Figure 4.

2.2 Execution

This phase of the SR has three steps according to the

guidelines proposed by Kitchenham (2004) (2007).

The first one is Studies Identification (Steps 2 to 5 of

Figure 1). In this step, the researcher should adjust the

search string using the keywords earlier defined in the

protocol. After this step, the strings should be applied

in each search engine, for example, IEEE, Scopus,

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

38

ACM, Springer and Web of Science. This action is

not supported by the tool and the search results must

be imported into StArt, As the studies are being

imported into the tool, it assigns a score for each

study according to the occurrences of the keywords

defined in the protocol, in the studies title, abstract

and keywords list. This score can be used, for

example, to establish an order of reading once studies

with higher scores should be more relevant to the SR.

Also, if the studies with higher scores are not relevant

to the research question, it is possible that the strings

should be revisited and improved. The string

definition is an important point to the success of SRs,

and its quality can be accessed through visualization

provide by StArt, which is explored and presented in

Section 4.

The second step is Studies Selection (Step 6 of

Figure 1). In this step, the researcher should use the

inclusion and exclusion criteria, defined in the

protocol, to classify the studies as accepted or

rejected. Duplicated studies are automatically

identified by the tool. When the study is accepted, the

researcher can attribute to it a relevance level (Very

High, High, Low or Very Low).

The third step is Extraction (Steps 7, 8 and 9 of

Figure 2). At this step, the researcher must read the

full version of each study “Accepted study”, elaborate

a summary and fill in the Information Extraction

Form of each study (Figure 4-B).

Aiming to facilitate this step, it is possible to link

the studies full text file (e.g. PDF files) with their

record in the tool.

2.3 Summarization

In this phase (Step 10 of Figure 2), StArt provides

the following facilities:

Easy access to the information of all studies

accepted in Extraction Step. Comments and

information extracted in previous steps can be

accessed and copied to a text editor added in the

tool. After collecting that information, the

researcher can transfer this initial version of the

summary to a more powerful text editor.

Generation of charts that support a quantitative

SR characterization. For example: the percentage

of studies identified by each search engine, the

percentage of studies accepted, rejected and

duplicated in Extraction step, the times that each

inclusion and exclusion criterion was used for

classifying the studies as accepted or rejected

(Figure 11). In fact, this kind of quantitative data

is particularly relevant for Systematic Mappings

(Petersen et al, 2008). In case the researcher

choose to do meta-analysis, carry out statistical

tests or elaborate other charts, StArt can generate,

among other reports, a spreadsheet that allows

data manipulation outside the tool. These reports

can be generated according to researchers’ needs,

based on options that allow grouping data in

different ways, (Figure 5-A), applying different

filters (Figure 5-B) and choosing specific

characteristics of the studies (Figure 5-C). Figure

5-D shows a preview of the report.

Deal with a large volume of data to discover

features, patterns and hidden trends through

visualization. When an SR or SM process is

finished, there is a large amount of data related to

the research topic that can show trends in the

evolution of the topic over time, which is

interesting information to explain the state of the

art. As mentioned before, the information

visualization is a helpful tool for knowledge

integration activities.

3 VISUALIZATION IN StArt

Considering the importance of quantitative data for

both the SR and SM and the fact that information

visualization explores the natural visual ability of

humans aiming to facilitate information processing

(Gershon, Eick, Card, 1998), StArt uses

visualization to facilitate knowledge management

about literature reviews. Using effective visual

interfaces, it is possible to quickly manipulate large

volumes of data to discover characteristics, patterns

and hidden trends.

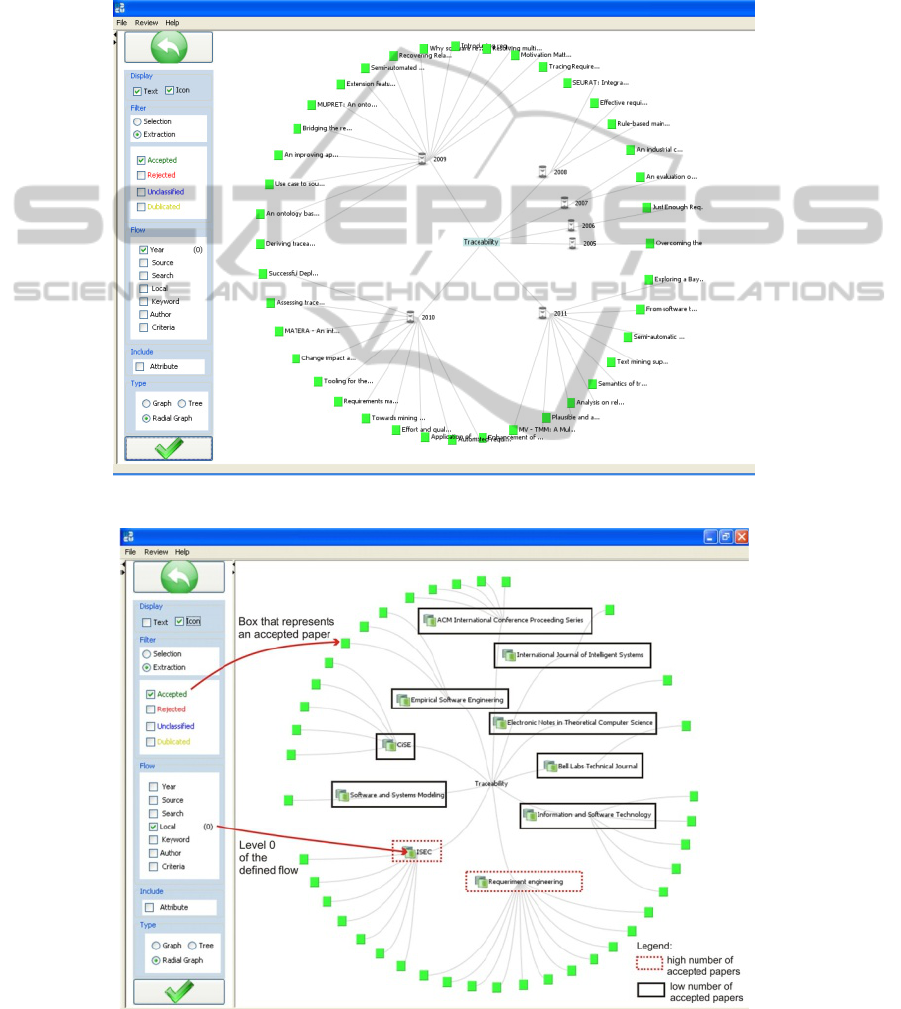

Based on visualization, for example, it is easier

to realize how a specific research topic evolved over

time. See Figure 6 where the researcher’s interest

was to understand how the topic “traceability” was

explored by the academic community, in relation to

the question investigated in this example. It is easy

to identify that in 2005 and 2006 there was only one

study published; in 2007 and 2008 there were few

additional studies, but in 2009, 2010 and 2011, the

number of studies that mentioned the research topic

was more significant than in the previous years.

To build this visualization, the researcher should

select the following options (Figure 6): green

rectangle representing an accepted study; part of the

study title nearby the rectangle, the publication year

as the grouping filter, and the Radial Graph as the

visualization technique.

Now, suppose that the researcher would like to

identify appropriated places for submitting a study

or for publishing results of a literature review. In this

ManagingLiteratureReviewsInformationthroughVisualization

39

Figure 3: Search engines defined in the protocol are automatically inserted under Studies Identification.

Figure 4: Relationship between attributes defined in the protocol and the form available during the Extraction step.

Figure 5: Options for specifying reports.

case he/she should select almost the same options

mentioned before, exchanging year by place. This

visualization (Figure 7), allows identifying the main

discussion forums for the topic under investigation.

Observe that some places have few studies related to

“traceability”, while some others have have more

publications on this topic. Besides, the visualization

type was Radial Graph and the studies titles were

omitted.

If the researcher wishes to merge both the

previous analysis in one graph, it would be better to

use a different visualization type. In this case the

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

40

Tree technique seems better, as shown in the

screenshot of Figure 8. The researcher can expand

the levels according to their need.

A double click on a selected study shows

information (like authors, abstracts, etc) about it.

In addition to the features described above,

visualization is also used to show the relationship

among the studies recovered in literature review.

This information allows evaluating the set of studies

and enhancing the search for them. This resource is

better explained in next section.

4 TEXT MINING IN StArt

According to Dunne et al. (2012), the growing

number of publications combined with increasingly

Figure 6: Visualization of publications on “traceability” over time.

Figure 7: Visualization of places where “traceability” has been published.

ManagingLiteratureReviewsInformationthroughVisualization

41

Figure 8: Visualization of places where “traceability” has been published according to the year.

cross-disciplinary sources makes it challenging to

follow emerging research topics and identify key

studies. It is even harder to begin exploring a new

field without a starting set of references.

During the conduction of literature reviews many

studies are retrieved from various search engines

through search strings. Hence, the researcher must

be careful not to leave out any studies that may be

relevant. According to Boell and Cezec-Kecmanovic

(2010), the usual problem of systematic reviews is

that the more inclusive the search strategy, the more

irrelevant studies will be retrieved; the more precise

and specific the search strategy, the more relevant

studies will be missed.

In order to help minimizing this problem, StArt

provides support to identify the references of each

study retrieved by the search strings. This support

allows knowing if there are studies not retrieved, but

referenced.

As the search engines generally do not provide

the list of references from each study, this

information is obtained by reading and extracting the

references of the PDF files of the retrieved studies.

Every time a PDF file is linked to a study, StArt

searches the references in the PDF file. Aiming to

identify information like authors, publication place

and title, regular expressions are used to identify the

bibliographic reference template that was used

(APA, Harvard, IEEE, etc.). To determine which

study is related to another one, the similarity

between the titles of the studies is calculated using

the text mining algorithm proposed by Salton

(1989). The result of this process is shown through

visualization as presented in Figure 9. The study in

the centre of the figure was not retrieved in the

literature review, but is referenced by five studies

that were retrieved.

This functionality is especially useful during the

execution of pilot literature reviews, which should

be conducted for adjusting the protocol and the

search strings, as suggested by Kitchenham (2007).

If there are studies not found but referenced many

times, the researcher should verify, for example, if

the keywords of these studies should be considered

in the protocol and search strings. If so, a new search

applying these new keywords must be performed

aiming to find relevant studies that were missed.

Start also offers the functionality for detecting

which of the studies imported into the tool are

similar. The similarity is calculated based on the

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

42

abstracts through Vector Processing Model (Salton,

Allan, 1994). The result of this processing is shown

in a table as presented in Figure 10. This table

provides a list of similar studies and their respective

similarity grade in relation to a study previously

selected

This list of similar studies can be used, for

example: (i) to define the next study to be analyzed;

(ii) to facilitate comparison between similar studies

and (iii) to make the inclusion and exclusion of

studies easier – studies with a high level of similarity

to an excluded study tend to be also excluded.

Other researches use text mining in the context

of SR or SM, but it is not available in tools that

support the whole SR or SM processes.

Malheiros et al. (2007) proposed the use of a

visualization tool, named PEx, to support the first

step of studies selection. PEx has a module that

processes the abstract of the primary studies,

eliminates stopwords, calculates the terms frequency

and, based on this result, displays clusters of studies

to facilitate their analysis.

Felizardo et al. (2011) continued the research

cited above presenting the VTM (Visual Text

Mining) tool which supports studies selection. Like

Malheiros et al. (2007), the result of text mining

processes is shown by different visualization

techniques which help applying the inclusion and

exclusion criteria previously inserted in VTM tool.

It is important to notice that the focus of these

studies is the studies selection step. On the other

hand, in Start, visualization and text mining are

currently being used to support the search string

definition and the SR or SM Summarization phase.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

This paper explored the use of visualization for

making easier the interpretation of data provided by

Systematic Literature Review and Systematic

Mapping. This visualization is available in StArt,

which also supports the steps of SR and SM

processes. As these processes are laborious, posses

Figure 9: Relationship among the studies uploaded into StArt and their references.

ManagingLiteratureReviewsInformationthroughVisualization

43

Figure 10: List of similar studies in relation to a selected study – the similarity grade is highlighted.

many repetitive steps and require that all information

is packed, the availability of computational support

is relevant.

Although there are some tools that have been

used by researches to aid the conduction of literature

reviews, most of them are reference manager. Some

examples are JabRef (jabref.sourceforge.net),

EndNote (www.endnote.com), ProCite

(www.procite.com), Reference Manager

(www.refman.com), RefWorks (www.refworks.com)

and Zotero (www.zotero.org). Only SLR tool

(Fernández-Sáez, Genero, Romero, 2010) focuses on

SR process (Kitchenham, 2007). However, it works

only on the English or Spanish versions of the

Windows operating system.

As StArt is closely associated to the SR and SM

processes, it provides many facilities that make

easier the conduction of these types of reviews.

Some characteristics that differentiate it from the

other tools are the score, which is calculated

automatically and can give insights on the paper

relevance; different types of data visualization that

can aid to map the research area; extraction of the

references of the studies gathered in the review, that

allows evaluating the adequacy of search strings and

improving the quality of the whole activity; and

other facilities that make the conduction of the

process more manageable.

Considering the importance of packing the SRs

or SMs data, StArt saves all data in a “.start” file

which allows conducting a review in sessions and

sharing a review with another researcher. In

addition, as StArt provides a simple text editor for

writing an initial summary of the state of the art, this

summary is also packed. StArt is being continuously

evolved and tested. The tool was also evaluated from

the perspective of its usefulness and ease of use,

according to the TAM model, which found that the

tool is useful to users and can be easily used by

researchers (Hernandes et al, 2010).

As future work, it is planned to continue the

development of StArt emphasizing the analysis

related to Systematic Mappings. This objective has

already initiated with the addition of visualization,

but there are other features that can enhance its

support for SM. Besides, it is planned some

experimental studies that aim to establish a strategy

to improve search strings based on the references of

ICEIS2012-14thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

44

the collected studies and also to explore the tool as a

support to conduct meta reviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the students and researchers who

have been used StArt and are giving constant

feedback to development team and CNPq, CAPES

and Observatório da Educação Project for financial

support.

REFERENCES

Boell, S. K., Cezec-Kecmanovic, D. 2010. Are systematic

reviews better, less biased and of higher quality?. In

Proc. European Conference on Information Systems,

Helsinki, Finland.

Burley, D. 2010. Information visualization as a knowledge

integration tool. Journal of Knowledge Management

Practice.

Dunne, C., Shneiderman, B., Gove, R., Klavans, J. &

Dorr, B. 2012. Rapid understanding of scientific paper

collections: integrating statistics, text analytics, and

visualization. JASIST: Journal of the American Society

for Information Science and Technology.

Felizardo, K.R. et al. Using Visual Text Mining to Support

the Study Selection Activity in Systematic Literature

Reviews”. In: Int. Symposium on Empirical Software

Engineering and Measurement, ESEM, 2011, pp. 77-

86.

Fernández-Sáez, A.M., Genero, M., Romero, F.P. SLR-

Tool: A Tool for Performing Systematic Literature

Reviews. In Proc. JISBD, 2010, pp.329-332.

Gershon, N., Eick, S.G., Card, S. 1998. Information

visualization interactions, ACM Interactions, ACM

Press.

Hernandes, E. C. M.; Zamboni, A. B.; Thommazo, A. D.;

Fabbri, S. C. P. F. Avaliação da ferramenta StArt

utilizando o modelo TAM e o paradigma GQM. In: X

Experimental Software Engineering Latin American

Workshop, ICMC-São Carlos.

Kitchenham, B. A. 2004. Procedures for Performing

Systematic Reviews. Software Engineering Group,

Keele University, Keele, Tech. Rep. TR/SE 0401.

Kitchenham, B. A. 2007. Guidelines for performing

Systematic Literature Reviews in Software. Software

Engineering Group, Keele Univ., Keele, Univ.

Durham, Durham, Tech. Rep. EBSE-2007-01.

Malheiros, V., Höhn, E., Pinho, R., Mendonça, M.,

Maldonado, J.C. “A Visual Text Mining approach for

Systematic Reviews”. In: International Symposium on

Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement,

ESEM, 2007, pp. 245-254.

Montebelo, R. P. et. al. 2007. SRAT (Systematic Review

Automatic Tool) Uma Ferramenta Computacional de

Apoio à Revisão Sistemática, In V Experimental

Software Engineering Latin American Workshop.

ICMC-São Carlos.

Pai, M., McCulloch, M., Gorman, J. D., Pai, N., Enanoria,

W., Kennedy, G., Tharyan, P., Colford Jr., J. M. 2004.

Clinical Research Methods - Systematic reviews and

meta-analyses: An illustrated, step-by-step guide. The

National Medical Journal of India.

Petersen, K. et al. 2008. Systematic Mapping Studies in

Software Engineering, In: Proc. Inter. Conf. on

Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering,

Bari, Italy.

Salton, G. 1989. Automatic Text Processing - The

Transformation, Analysis and Retrieval of Information

by Computer. Addison-Wesley.

Salton, G., Allan, J. Text Retrieval Using the Vector

Processing Model. In Symposium on Document

Analysis and Information Retrieval. University of

Nevada, Las Vegas, 1994.

Zamboni, A. B.; Thommazo, A. D.; Hernandes, E. C. M.;

Fabbri, S. C. P. F. StArt Uma Ferramenta

Computacional de Apoio à Revisão Sistemática. In:

Brazilian Conference on Software: Theory and

Practice - Tools session. UFBA.

ManagingLiteratureReviewsInformationthroughVisualization

45