Search Engine Optimization Meets e-Business

A Theory-based Evaluation: Findability and Usability as Key Success Factors

Andreas Auinger

1

, Patrick Brandtner

1

, Petra Großdeßner

2

and Andreas Holzinger

3

1

Department for Digital Economy, School of Management, Upper Austria University of Applied Sciences, Steyr, Austria

2

BMD System Software, Online Marketing, Steyr, Austria

3

Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Documentation,

Research Unit Human-Computer Interaction, Graz, Austria

Keywords: Search Engine Optimization, Usability, ISO Criteria, Eye Tracking, Usability Evaluation.

Abstract: What can not be found, can not be used. Consequently, the success of a Website depends, apart from its

content, on two main criteria: its top-listing by search engines and its usability. Hence, Website usability

and search engine optimization (SEO) are two topics of great relevance. This paper focusses on analysing

the extent that selected SEO-criteria, which were experimentally applied to a Website, affect the website’s

usability, measured by DIN EN ISO 9241-110 criteria. Our approach followed (i) a theory-based

comparison of usability-recommendations and SEO-measures and (ii) a scenario- and questionnaire-based

usability evaluation study combined with an eye-tracking analysis. The findings clearly show that Website

usability and SEO are closely connected and compatible to a wide extent. The theory-based measures for

SEO and Web Usability could be confirmed by the results of the conducted usability evaluation study and a

positive correlation between search engine optimization and Website usability could be demonstrated.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today, the Internet is the most important medium

for consumers all over the world. Index measures of

44% for UK, 45% for Germany and 46% for France

show that it is now twice as important as TV

(McRoberts and Terhanian, 2008). Besides its

importance as a research tool, communication and

entertainment platform, it is a fact that

approximately 97% of the internet users (Kaspring,

2011) consult the Web as their main information

source when making purchasing decisions (“search

before the purchase”). To benefit from the Internet

as a company, the aim should be pursued to lead as

many visitors as possible to one’s own web

offerings. Furthermore, the optimization of the

website usability with the aim of conforming to user

expectations all over the world (Auinger et al.,

2011), it is equally important to achieve a top

position in search engine results. End-users should

be able to use a website; however, before they can

use it, they must find it, even by using a standard

search engine (e.g. Google).

In the literature, a number of policies and

measures can be found, which have to be taken into

consideration when designing a useable and search

engine-friendly website (Nielsen, 1993, Nielsen and

Loranger, 2006; Leavitt and Shneiderman, 2006

etc.), (Hearst, 2009), (Baeza-Yates et al., 2011).

Different aspects must be considered with mobile

search (Bloice et al., 2010).

SEO is of high relevance, especially for E-

Business, because more than 60% of search engine

users click only on the results that appear on the first

search engine results page (SERP) and less than

10% of users click on results that appear after the

third page (Malaga, 2008).

If “ease of use” is a primary goal of Web

usability, then “findability” is the most critical

concept, because both accessibility and usability

depend upon findability (White, 2003).

For this reason, this paper will address search

engine optimization as well as web usability. The

aim is to analyze to what extent proven SEO-

measures reconcile with established usability-

guidelines. To be more precise, this paper analyzes

to what extent applied SEO-recommendations affect

website usability.

To meet this objective, the paper first outlines

the topic of usability and the implementation of

usability guidelines within the DIN EN ISO 9241-

237

Auinger A., Brandtner P., Großdeßner P. and Holzinger A..

Search Engine Optimization Meets e-Business - A Theory-based Evaluation: Findability and Usability as Key Success Factors.

DOI: 10.5220/0004062302370250

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Communication Networking, e-Business and Optical Communication Systems (ICE-B-2012),

pages 237-250

ISBN: 978-989-8565-23-5

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

110 standard. Hence, the understanding of usability

in the course of this paper is focused on the

fulfillment of those guidelines. Furthermore, not

only recommendations found in ISO Standard 9241-

110 but also relevant literature and recommended

guidelines of acknowledged usability-experts were

taken into consideration.

Secondly, the topic of search engine

optimization is dealt with, and on-site measures and

factors that are crucial for a top ranking in search

engine results lists are analyzed. In a next step, the

SEO-measures are examined with regard to their

impact on website usability. A theory-based

comparison of usability recommendations and SEO-

measures is then conducted. To further refine results

and validate findings, a usability evaluations study is

part of the present paper. Hence, the defined

objective is approached based on theory found in

literature as well as based on the results of the

conducted usability evaluation study.

2 WEB USABILITY AND ITS

IMPLEMENTATION

A generally applicable definition of usability can be

found in ISO Standard 9241 (ISO 9241:2006:

Ergonomics of human-system interaction, 2006).

ISO Standard 9241-110 sets seven dialog

principles for human-system interaction (ISO 9241-

110:2006: Dialogue principles, 2006):

suitability for the task

self-descriptiveness

conformity with user expectations

suitability for learning

controllability

error tolerance

suitability for individualisation

In addition to those seven principles the ISO

9241-110 provides over 50 recommendations for

implementing usability.

In the course of the present study, those seven

principles were taken as a reference framework to

point out principles for designing a useable system.

Therefore, the recommendations in ISO Standard

9241-110 were enriched by suggestions and

guidelines of prestigious usability experts. This

section outlines how the particular dialog principles

can be implemented in practice. Because these

recommendations will be used later on in this paper

they are provided with shorthand symbols, apposite

to the particular dialog principle.

2.1 Implementing Suitability for the

Task (T)

A website is suitable for a certain task if it supports

users getting a particular task done. That means that

functionality and design of dialog are based on the

characteristic attributes of the task, rather than on

those of the applied technology. (ISO 9241-

110:2006: Dialogue principles, 2006).

To implement the suitability for the task, certain

recommendations can be found in the relevant

literature (e.g.(Gould, 1991), (Diaper, 2002),

(Holzinger, 2005)).

Cross-platform Design (T1): To ensure that a

website is suitable for a certain task, designers on

the one hand have to consider that the right

information is provided. On the other hand, they also

have to deal with limitations and constraints due to

different hardware and software employed by the

users (Leavitt and Shneiderman, 2006).

Hence, it is necessary to consider different web

browsers, operating systems, screen resolutions and

hardware (Nielsen and Loranger, 2006).

Separation of Content and Design (T2): To

make sure that a website is accessible for a wide

public, it is essential to stick to certain web

standards. Separating content and structure (HTML)

from design (CSS) provides the basis for that

(Bornemann-Jeske, 2005) and allows a higher

flexibility, e.g. when a website is viewed on multiple

output devices, which has positive effects on the

accessibility (Krug, 2006).

Visual Clearness (T3): To ensure that a website

is easy to understand and suitable for a certain task,

it is necessary to follow a consistently defined

structure. “Visual clearness” states that each website

should be clear in presentation, correctly aligned,

should not convey an impression of being

overloaded and its components should be easy to

comprehend (Stickel, Ebner & Holzinger, 2010).

Content and Page Structure (T4): To support

users in finding relevant information in a timely

manner, important information should be placed at

the top of a webpage. Thereby scanning and

comprehending content is considerably facilitated

(Herendy, 2009) . During scrolling, headings should

be constantly visible or at least repeated (Leavitt and

Shneiderman, 2006).

Writing for the Web (T5): Information in text

format should be presented clear and simply and

should comply with three rules: text on the web

should be scanable, short, precise and objective

(Morkes and Nielsen, 1997). Hence, meaningful

headings, highlighted keywords and lists and

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

238

enumerations should be used while excessive

adjectives and buzzwords should be avoided.

Typography & Colour Scheme (T6): The

legibility of a website is a crucial factor of success

(Nielsen, 2000). Therefore, standard fonts and an

adequate and adjustable font size should be

provided, whereas animated text and text in capital

letters only should be reduced or avoided entirely.

Scrolling and Paging (T7): There is no general

rule on whether scrolling or paging is more

convenient for presenting information on a website.

However, studies showed that especially elderly or

inexperienced people are significantly slowed down

by scrolling and would prefer paging. Nevertheless,

when it is a matter of reading comprehension,

information on a single page is perceived more

related (Leavitt and Shneiderman, 2006)

Pop-ups (T8): Information that is not needed in

order to complete a certain task should not be

displayed (ISO 9241-110:2006: Dialogue principles,

2006).

Pictures and Graphics (T9): To keep loading

times low, image files should not be too large. When

high-resolution images are available, thumbnails

should be provided (Leavitt and Shneiderman,

2006). Text in pictorial form should be avoided and

each image should be provided with alternative text

to support screen readers and improve accessibility

(Nielsen and Loranger, 2006; Krug, 2006)

Animation and Flash (T10): Animated website

elements are likely to distract and annoy users and

often cause usability problems (e.g. with

bookmarking or by deactivating the back button).

Hence, they should only be used when conveying

information can be countenanced, e.g. for presenting

motion sequences (Manhartsberger and Musil,

2001). Especially Flash-animations often cause

usability and accessibility problems (Nielsen and

Loranger 2006; Broschart, 2010).

Multimedia Content (T11): Multimedia content

should be used with caution and only when added

value is created and interacting with the website is

facilitated (Nielsen and Loranger, 2006).

Furthermore, alternative text or subtitles should be

provided for disabled users (Lynch and Horton,

2008).

Frames (T12): Frames are used to separate

navigation from content. Thus navigation has a fixed

position on a website while at the same time content

can be scrolled. Nevertheless, frames also implicate

a lot of disadvantages, e.g. when setting bookmarks

or printing websites (Manhartsberger and Musil,

2001). Therefore, frames are only used within limits

(Broschart, 2010).

Design of Forms (T13): Forms should be kept

as simple and lean as possible. The less data a user

has to put in, the higher the probability that he will

fill out the entire form. On account of this redundant

inputs, such as zip code plus federal stat, should not

be requested (Fischer, 2009). The acceptance of

forms can also be increased by providing selectable

default values which are recommended to facilitate

the input of data (Manhartsberger and Musil, 2001).

2.2 Implementing Conformity with

User Expectations (E)

A website should always be designed to meet user

expectations. Every action a user conducts is

associated with certain expected results. If a website

does not consistently deliver the same expected

results it can easily lead to a confused user. The

following recommendations explain how to meet

user expectations (Manhartsberger and Musil, 2001).

Consistency and Conventions (E1): If a

website is designed in a consistent way, this will

also increase the predictability when interacting with

it. Users know which functionality to expect where

and how to get to a desired result. Therefore, it is

important that design elements have a fixed position

and a consistent terminology is used. (Nielsen and

Loranger, 2006; Leavitt and Shneiderman, 2006)

User-oriented Information Architecture (E2):

A user visits a website to get a certain matter done as

quickly and simply as possible. This matter could

e.g. be to gather information about or to purchase a

desired product. The website operator on the other

hand wants to present himself and advertise and sell

his products. As a result of those two positions

websites are often designed following the website

operator’s needs rather than those of the customers

(Nielsen and Loranger, 2006). Measures to avoid a

situation like this include; keeping navigation as

simple and as expectation-conform as possible and

putting similar elements side by side (Fischer, 2009).

Expectation-conformal Positioning and

Presentation of Important Website Elements

(E3): Despite the necessity of an individual website

structure there are certain web-standards and

generally applicable conventions. Standards and

conventions facilitate the human-system interaction

by using established elements (Krug, 2006). This

includes a fixed, expectation-conform position and

design for navigation elements, the search function

and the corporate logo.

Presentation of Hyperlinks (E4): A hyperlink

should always work as the user expects it to: when

the link is clicked, the desired result is delivered.

Search Engine Optimization Meets e-Business - A Theory-based Evaluation: Findability and Usability as Key Success

Factors

239

Hence, expectation-conformity of hyperlinks is very

important (Fischer, 2009). Hyperlinks should

therefore be underlined, blue if they have not been

clicked yet and violet if they have been clicked

(Cappel and Huang, 2007; Nielsen, 2000).

Use of Interactive Controls (E5): To enable

human-system interaction different control elements

are used: mainly hyperlinks, radio-buttons,

checkboxes, pull-down menus and input fields

(Manhartsberger and Musil, 2001). Although those

controls are widely known it is important to make

sure they work in the expected and conventional

manner (Lynch and Horton, 2008).

Feedback and Status Display (E6): Every

website should deliver direct and expectation-

conforming results and feedback to user actions. If a

direct result cannot be delivered the user should be

informed about the delay and when the result can be

expected (ISO 9241-110:2006: Dialogue principles,

2006). For instance, when the download of a large

file is requested, a status display should inform the

user about the remaining download time (Nielsen

and Loranger, 2006). Another example would be a

progress bar during the process of buying products

in a web shop (Erlhofer, 2011).

2.3 Implementing Self-Descriptiveness

(SD)

According to Krug’s first law of usability “Don’t

make me think!” a website should be self-

descriptive. Users should be able to realize what a

website is about without long-winded thinking

(Krug, 2006).

Clear Navigation (SD1): Navigation allows

users to move between the different pages and parts

of a website. To make navigation structure as clear

and self-descriptive as possible, it should always

answer the following question: where is the user

right now, where has he been before and where can

he go from here (Nielsen, 2000).

Page Titles and Bookmarks (SD2): The title of

a webpage is displayed on the upper left of a web

browser. Although this area is not in direct user

focus, a page title is important for search engines,

reference purposes and for setting bookmarks

(Leavitt and Shneiderman, 2006; Nielsen and Tahir,

2002). With standard Websites setting bookmarks is

simple but can become a problem area when

technologies, such as AJAX are used. AJAX

facilitates designing interactive and optically

appealing websites (Holzinger et al., 2010).

Regarding bookmarks AJAX makes it problematic

to bookmark particular content because the URL

does not change (Carl, 2006).

Meaningful Headings (SD3): Meaningful

headings are of great significance for making

content scannable, supporting user orientation and

for structuring. Headings should always be provided

with appropriate HTML-tags and should be defined

distinctive and clear (Leavitt and Shneiderman,

2006; Nielsen, 2000).

Navigation Wording (SD4): Every navigation

element should have a distinctive, clear and

meaningful description (Nielsen and Loranger,

2006). Hyperlinks should give an indication of

where they lead, the language used should be

adapted to the users’ language, unknown

abbreviations and wordings should be avoided

(Lynch and Horton, 2008; Fischer, 2009; Nielsen

and Loranger, 2006).

Self-explanatory Icons and Symbols (SD5):

Icons and symbols should be self-descriptive, but

only a few – e.g. the printer or the magnifier icon -

really are. According to Fischer icons usually show

objects but trigger a process. Hence, users can easily

get confused and icons should only be used if they

are widely known and can easily and doubtlessly be

interpreted (Fischer, 2009).

Labelling of Input Fields (SD6): A logical

arrangement as well as a clear and distinctive

description of input fields should be used and

information on how to fill out a form should be

provided (Nielsen and Loranger, 2006;

Manhartsberger and Musil, 2001).

2.4 Implementing Suitability for

Learning (L)

A system or a website is suitable for learning if users

receive support and instructions when needed.

Suitability for learning contradicts other dialog

principles because a self-descriptive, expectation-

conformal, error-tolerant, controllable and

customisable website should not need to be learnt

(Arndt, 2006). Nevertheless, a website which is too

complex and cannot be understood instantly by the

user will lead users to leave if there is no form of

support whatsoever (Nielsen and Loranger, 2006).

Help (L1): The need for a help function depends

on the users' experience and the complexity of a

website. If complicated and non-standard

functionalities are used, it is advisable to provide a

separate help area (Broschart, 2010).

Guided Tour (L2): A guided tour makes sense

when a website offers revolutionary or unknown

features. In that case, it can help users to understand

the way the website works (Jacobsen, 2005).

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

240

Frequently Asked Questions (L3): Frequently

asked questions (FAQs) must not be confused with

the help function: FAQs are meant to list the most

common user questions and the answers to them.

Furthermore, FAQs are usually used for product or

company related rather than for usability questions

(Manhartsberger and Musil, 2001).

Sitemap (L4): A sitemap allows the user to

obtain a quick and simple overview of a website and

provides orientation aid. It is usually presented in a

tree structure and consists of logically arranged

groups of hyperlinks (Balzert and Klug and

Pampach, 2009).

2.5 Implementing Controllability (C)

A dialog is controllable when users are able to start

it and to influence its direction and speed until a

desired result is reached (ISO 9241-110:2006:

Dialogue principles, 2006).

Process Control Navigation (C1): Clearly

structured and easy to use navigation is a key

element to navigation through multi-step processes,

such as the order process one can find in web shops:

users should be able to realize in which part or step

of the process they are at the moment, how many

process steps there are in total and they should have

the possibility to switch between the different steps

(Broschart, 2010).

Supporting Keyboard-operated Input (C2):

Many internet users are not equipped with a mouse,

because they are using devices, such as mobile

phones or speech commanded input devices. Hence,

all website elements should also be controllable via

a keyboard (Lynch and Horton, 2008).

Deactivating the Back Button and Opening

New Browser Windows (C3): According to

Nielsen and Loranger, deactivated back buttons, and

opening new browser windows without notification,

rank among the biggest usability mistakes and

should be avoided entirely (Nielsen and Loranger,

2006). Especially AJAX causes problems with back

buttons (Carl, 2006).

Controlling Multimedia Elements (C4): Users

should always know what to expect, so that they do

not have to invest redundant time in playing or

downloading multimedia files. A summary of its

content could precede a video file and the indication

of a file’s size and the estimated download file could

help users to decide whether to download it or not

(Nielsen, 2001; Lynch and Horton, 2008).

Designing Printer-friendly Pages (C5):

Information often needs to be printed to share it

offline e.g. in a company. Hence, each page should

be printable. The print version should contain the

total content in one file und should be formatted in a

printer friendly way (Fischer, 2009; Nielsen, 2001).

2.6 Implementing Error Tolerance

(ET)

A website can be regarded as error tolerant if a

desired result can be obtained despite incorrect

input. Hence, errors have to be detected early and

support for error correction has to be provided (ISO

9241-110:2006: Dialogue principles, 2006).

Error Prevention (ET1): Most errors occur due

to incorrect or incomplete input to forms, which is

often caused by insufficient labelling of mandatory

fields or by unclear description of the input format.

Thus, input fields should be accurately described,

the maximum number of characters stated and non-

permitted characters indicated (Fischer, 2009).

Error Detection and Correction (ET2): A

usable website should provide immediate feedback

when incorrect input was made. Hence, a website

should not only detect but also give an indication of

how to correct errors. Error messages should easily

be identifiable as such, clearly assignable to a

particular input field and should provide short and

meaningful feedback on how to correct any errors

made (Fischer, 2009; Manhartsberger and Musil,

2001; Lynch and Horton, 2008). Technologies, such

as JavaScript or AJAX support validating input

during the input process itself, respectively directly

after the input is confirmed (Broschart, 2010). One

big disadvantage of validating input with AJAX or

JavaScript is the fact that JavaScript has to be

activated in the users browser, therefore server-sided

validation should not be omitted (Wenz, 2007).

2.7 Implementing Suitability for

Individualisation (I)

A website is suitable for individualisation when

users can adapt interaction, presentation and content

to their specific needs (Arndt, 2006).

Personalising a Website (I1): Personalising a

website means that individual, user-specific content

is provided. There are different ways of how a

website can be personalised: e.g. customizable

layout, individually selectable content or scalable

font size (Broschart, 2010; Balzert and Klug and

Pampuch, 2009).

Search Engine Optimization Meets e-Business - A Theory-based Evaluation: Findability and Usability as Key Success

Factors

241

3 ON-SITE SEARCH ENGINE

OPTIMIZATION

Search engine optimization (SEO) describes the

process of “how to” and methods used to improve a

website’s rank in organic search results (Lammenett,

2010), (Chen et al., 2011). When talking about SEO,

one has to distinguish between on-site and off-site

optimization. On-site optimization encompasses all

methods which can be implemented on the website

itself, e.g. content, source-code or keyword

optimization (Erlhofer, 2011; Bischopinck and

Ceyp, 2009). Off-site optimization on the other hand

involves methods which are implanted on third party

websites, e.g. external linking (Lammenett, 2010).

Since the aim of the present study was to analyze

the influence of implemented SEO-methods on

website usability, off-site methods will not be

relevant for this paper. Hence, the following sections

deal with on-site SEO methods only.

3.1 Accessibility for Search Engines

Website accessibility describes the fact that a

website can be accessed independent of physical

user attributes or of hardware used. Furthermore, an

accessible website can be analysed and processed by

search engines without any problems (Erlhofer,

2011).

Using Appropriate File Formats: In order that

websites can be listed in search engine results, they

have to be indexable. More precisely, the website

content has to be searchable, analysable and rateable

according to its relevance. Hence, only search

engine friendly file formats should be used. Besides

HTML-documents; text files, PDF-Files, MS-Office

files and structured XML-formats, such as RSS can

be indexed easily (Bischopinck and Ceyp, 2009;

Broschart, 2010; Erlhofer, 2011). Nevertheless,

HTML is the best choice for relevant content,

because it is most appropriate for being processed

and analysed by search engines (Bischopinck and

Ceyp, 2009).

Valid HTML-Code and Use of CSS: Correct

use of HTML and CSS is a key factor for successful

SEO. Hence, syntax errors have to be avoided

entirely (Erlhofer, 2011).

Potential Problem Areas: Web designers often

want to create an extraordinary website and leave

search engine relevant technical aspects aside

(Broschart, 2010). Especially the use of dynamic

content, frames, Flash, JavaScript or AJAX is

frequently at the costs of usability.

Robots.txt: The robots.txt-file can influence

websites indexation behaviour. This file is located in

the root directory of the webserver and is requested

before crawling (Erlhofer, 2011). In this file, one can

define which directories and files may be accessible

for crawlers and which are hidden (Bischopinck and

Ceyp, 2009).

3.2 Navigation and Page Structure

A logically structured navigation and page

construction enables users to navigate through a

website intuitively. Furthermore, it is also of great

significance when the site is processed by search

engines (Erlhofer, 2011).

Overall Structure and Directory Depth: The

deeper a file is located in the file directory the more

irrelevant it is interpreted by search engines

(Erlhofer, 2011). Also the number of clicks it takes

to access a file is important for search engines

(Broschart, 2010). Hence, important files should be

placed high in file directory and should easily be

accessible for users.

Meaningful Directory and File Names: Search

engines also analyse the URL when processing a

document. Therefore, file directory and file names

should be specified carefully and relevant keywords

ought to be used (Alby and Karzauninkat, 2007).

Internal Link Structure: As mentioned before,

the number of clicks it takes to access a file is

important for search engines. Relevant content

should hence be placed as close to the homepage as

possible and direct links to access those files should

be provided (Broschart, 2010). Sitemaps and other

subscript lists offer further starting points for search

engines (Erlhofer, 2011).

3.3 Search Engine Relevant Entries in

Website Headers

An HTML-document consists of a header and a

body: the header contains the document title and

additional information, the so called meta-

information. Meta-tags are not visible for users but

are relevant for search engines (Fischer, 2009).

Page Title: The page-title is one of the most

important ranking criteria for search engines. Hence,

it should represent the documents content as

accurately as possible (Broschart, 2010).

Meta Tags: In the past, meta-tags were often

used to analyse and rank websites. Due to the misuse

of meta-tags to manipulate search results, a number

of search engines either minimized the impact of

meta-tags on their ranking system or do not consider

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

242

them at all (Erlhofer, 2011).

3.4 Text Optimization

Search engines operate text based and still have

problems dealing with images, pictures and Flash.

Hence, text optimization plays a key role for SEO

(Lammenett, 2010).

Keyword-oriented Writing: Keyword-oriented

text design is very important for search engine

oriented writing. Therefore, the keywords which

were defined during keyword research have to be

integrated in the webpages’ content to enable a

simple indexation of content (Erlhofer, 2011). There

are three factors influencing search engine ranking:

keyword density, keyword prominence and keyword

proximity.

Amount of Text: The optimal amount of text

can only be defined with due regard to usability

(Broschart, 2010).

Headings and Mark-up: Headings should be

defined using HTML-tags and should be simple and

clear. Furthermore, they are relevant for search

engines, lists and mark-up text and should therefore

be used purposefully (Erlhofer, 2011).

Alt-attribute: Due to the fact that search

engines are not yet able to interpret images and

graphics reliably and that disabled users often have

problems with them, providing alternative text is of

great significance (Broschart, 2010; Bischopinck

and Ceyp, 2009).

Content is King: According to IAB

Switzerland, unique and high-quality content is the

most important ranking criteria for search engines.

Hence, providing topic-relevant content of high-

quality is a key factor for SEO (IAB Switzerland,

2010).

4 SEO-METHODS AND THEIR

EFFECT ON USABILITY

SEO-methods are influencing website usability and

vice versa. The following tables sum up in detail,

which SEO-methods have which effect on the

usability criteria mentioned. Therefore, the SEO-

methods presented in section three are assigned to

the web usability guidelines and its effects described

in section two. Positive effects are marked with

“(+)” and negative with “(-)” .

Table 1: Accessibility for search engines and its effects on

usability.

SEO-methods

Effects on usability

Appropriate file formats:

primarily HTML-files,

PDF, .txt, .rtf. or MS-

Office documents

(+) supports accessibility (T2)

(+) makes content accessible for

screen readers (T2)

Valid HTML-Code and

use of CSS:

Semantic

characterization of

content

(+) supports accessibility (T2)

(+) facilitates access for screen

readers (T2),(T5)

(+) smaller HTML-files

reduction of loading time (T2)

(+) Enables individual design for

different output devices (T2),(C5)

Potential problem areas:

Dynamic contents,

frames, Flash, JavaScript

and AJAX

(+) AJAX makes interactive

websites possible (SD2)

(+) JavaScript and AJAX supports

validating inputs during input

process (ET2)

(-) Frames, Flash and AJAX are

potentially problematic for

bookmarking (T10), (T12), (C2)

(-) Frames can cause printing

problems (T12)

(-) Flash and AJAX deactivate the

browsers back-button (T10), (C3)

(-) Flash-animation is not acces-

sible for screen readers (T10)

(-) Inappropriate Flash-animation

distracts and disrupts users (T10)

(-) Long Flash-intros take

bandwidth and annoy users (T10)

(-) Without having JavaScript

activated in the browser,

JavaScript and AJAX-applications

cannot be run (ET2)

Robots.txt

No effects on usability

Table 2: optimal navigation and page structure and its

effects on usability.

SEO-methods

Effects on usability

Overall structure and

directory depth:

Logical navigation and

page-structure, flat link

and directory structure

(+) supports visual clearness and

site control (T3),(C1)

(+) facilitates search for

information (T4)

Directory and file

names:

Meaningful terms and

relevant keywords

(+) directory and file names are

part of the URL (SD1),(SD4)

(+) An URL with a descriptive

name is more professional an

trustworthier (SD1),(SD4)

Internal link structure:

Flat link structure,

descriptive link titles,

sitemap and subscript

lists as starting points

(+) a flat link structure supports

efficient working (T4)

(+) meaningful link titles support

predicting its content (SD4)

(+) sitemaps provide a table of

contents an support capturing a

websites structure (L4)

Search Engine Optimization Meets e-Business - A Theory-based Evaluation: Findability and Usability as Key Success

Factors

243

Table 3: Search engine relevant entries in website headers

and its effects on usability.

SEO-methods

Effects on usability

Descriptive page title:

individuality and context

relevance

(+) supports finding and

distinction between websites in

browser history, favourites and

bookmarks (SD2)

Meta-tags

No effects on usability

Table 4: Text optimization and its effects on usability.

SEO-methods

Effects on usability

Keyword-oriented

writing:

Consideration of

keyword density,

prominence and

proximity

(+) Using keyword supports scanning

and helps identifying relevant

information (T5)

(+) too high density influences text

readability and understand-ability, text

may appear ex-aggerated and

unprofessional (T5)

Optimal amount of

text:

dependent on

context, from a half

up to two pages

(+) short and precise text without

redundant information is preferred by

users (T5)

(+) short pages avoid scrolling, longer

pages facilitate fast and continuous

reading (T4),(T5),(T7)

Using headings and

mark-up

Apply suitable

HTML-tags

(+) improves website scannability (T5)

(+) provides orientation marks (T5)

(+) supports accessibility (T5)

(+) facilitates access for screen readers

(T5)

Using the ALT-

attribute

Providing

alternative text for

images

(+) Offers text alternative for disabled

people (screen reader) and users of

text-browsers (T9)

(+) Supports accessibility (T9)

Content is king

(-) duplicate content appears

unprofessional (T5)

(+) unique and high-quality content

generates additional value for users

and increases trust (T5)

Collectively, it can be concluded that SEO-methods

also lead to improved website usability and that

these two areas are closely connected. Furthermore,

the following statements can be made:

Search engine optimized websites are more

accessible because they facilitate using a

website for visually handicapped people

Search engine oriented text improves website

usability by increasing scannability and

readability

SEO-methods primarily meet the requirements

of the ISO 9241-110 dialog principle

“suitability for the task”

Except for meta-tags and the robots.txt-file, all

quoted SEO-methods have effects on usability

Potential SEO-problems also have negative

effects on usability

Decisive contradictions between SEO-

methods and usability could not be found

5 USABILITY EVALUATION OF

SEO OPTIMIZED WEBSITES

To further analyse the effects of SEO-methods on

website usability, a scenario-based usability

evaluation study was conducted. The goal of this

study was to determine if, and to what extent, SEO

influences effectiveness and efficiency of task

accomplishment and user satisfaction. In the

following sections, study design and results will be

presented.

5.1 Study Design

The usability evaluation study includes an eye

tracking analysis with additional questionnaires to

qualitative refine the results. The study followed a

determined design, which will be described in

sections 5.1.1 to 5.1.4.

5.1.1 Test Object

The usability evaluation study was conducted in

cooperation with BMD Systemhaus GmbH, a local

software house in Steyr that made their website

available as a test object. The target audience of this

website is professionally qualified but has only little

interest in technological issues.

5.1.2 Test Subjects

To ensure that the selected test subjects correspond

to the website’s target audience, test users were

selected from students of topically matching study

courses. In total, 22 students of different ages and

experience levels (fulltime and extra-occupational)

participated in the study.

5.1.3 Test Scenarios

Four different scenarios were designed to conduct

the usability evaluation study. For each scenario,

two versions of one webpage were used: one version

was optimized according to SEO requirements (on-

site optimization) while the other one was left

entirely unchanged and was equivalent to the

publically accessible version of the website, as

shown on the screenshot below:

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

244

Figure 1: Unchanged version of a test page.

The optimized versions of the webpages were

changed with regards to the following SEO-criteria:

Focus on defined keywords: three terms max.

per document, consider context relevance,

keyword density and keyword prominence,

use synonyms.

Use meaningful page-titles (title-tags)

Structure content by using headings, lists and

mark-ups

Write according to the inverted pyramid style

Use internal links

Define meaningful alternative text (alt-attr.)

The screenshot below shows the optimized version:

Figure 2: Optimized version of a test page.

Thus, the current usability evaluation study

focussed on content and text optimization, page

structure and navigation were negligible.

To make it possible to contrast them, the two

versions were shown to different subject groups: the

unchanged versions were presented to group A and

the optimized ones to group B.

In each scenario, test subjects were given the

task of informing themselves about a certain topic or

keyword. For this task, the unchanged page version

was shown to group A and the optimized one to

group B, each was displayed for a defined timespan:

In scenario one (“One2Meet”) the test pages

were shown for 30 seconds while in scenarios two

(“Controlling Software”), three (“Financial

Accounting”) and four (“Costing Software”) they

were shown for 60 seconds. Those timespans were

not chosen randomly but correspond to the pages’

actual visitor retention time from Google Analytics

which indicates how long users stay on the webpage

on average.

5.1.4 Test Procedure

As mentioned before, the conducted usability

evaluation study consisted of four scenarios,

whereby in each scenario different tasks had to be

solved. Before solving the respective tasks, users got

a brief introduction to the page and were prompted

to inform themselves about the given topic.

When users were ready, the page was shown for

the defined timespan, during which eye movement

was recorded by using an eye tracking system.

After each task, users were given a scenario-

specific questionnaire containing questions about the

content and the topic of the page. Furthermore, users

had to evaluate the fulfilment of the characteristics

of presented information as found in ISO 9241-12

(ISO 9241-12:1998: Presentation of information,

1998):

Clarity

Discriminability

Conciseness

Consistency

Detectability

Legibility

Comprehensibility

After completing the eye tracking for each of the

four different scenarios, another questionnaire

containing seven general questions was handed out.

This questionnaire had to be answered considering

all four scenarios at once.

Search Engine Optimization Meets e-Business - A Theory-based Evaluation: Findability and Usability as Key Success

Factors

245

5.2 Study Results

In the following three sections, the results of the

usability evaluation study will be presented: First,

evaluation of scenarios-specific questionnaires

allows drawing conclusion as to the efficiency of

task accomplishment and perceived quality of

information presentation. Second, eye tracking

analysis results are presented, followed by an

evaluation of the general questionnaires handed out

after all four scenarios were completed.

5.2.1 Evaluation of Scenario-Specific

Questionnaires

The evaluation of scenario-specific questionnaires

clearly shows that group A, who was given the

unchanged page versions, had far more difficulty

answering the questionnaire than group B, who was

given the optimized version. When being asked

comprehension questions, for example: to describe

page content and summarize content-related topics,

group B performed noticeably better than group A.

The following charts illustrate those findings

based on the results from scenario one “One2Meet”:

Figure 3: Comprehension of One2Meet (1).

Figure 4: Comprehension of One2Meet (2).

In addition to comprehension questions,

enumeration questions were part of the scenario-

specific questionnaire. These questions were asked

in order to analyse how many specific content-

related details users were able to remember,

depending on which version (unchanged and

optimized) they were shown. Therefore, the

questionnaire particularly asked for specifics, such

as fields of application, planning levels of the

particular tool, single functionalities, tool areas, new

improvements or development details. For this

purpose, a mixture of open questions and multiple

choice questions was applied, as the following table

shows:

Table 5: composition of enumeration questions applied.

Question

Choices

Correct answers

Scenario 1,

question 3

10

6

Scenario 2,

question 1

open question

3

Scenario 2,

question 2

8

4

Scenario 3,

question 1

9

6

Scenario 3,

question 2

open question

4

Scenario 3,

question 3

open question

1

Scenario 4,

question 1

open question

4

Scenario 4,

question 2

open question

5

When multiple choice questions were asked, test

subjects were given the number of right answers,

which was at the same time the maximum number of

choices allowed. Open questions had to be answered

without any answers to choose from.

The following charts visualize the differences in

results between subject group A (unchanged page

version) and subject group B (optimized page

version):

Figure 5: Participants’ enumeration of specific points in

scenario 3, question 1, refer to table 5.

As figure 5 clearly shows, subject group B, who was

shown the SEO-optimized page version, performed

considerably better in terms of remembering specific

points than subject group A. This could also be

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

246

found in all the other scenarios.

In total, the average percentage of correct

answers in subject group A was about 42%, while in

subject group B 69% of all answers were correct:

Figure 6: comparison of percentage of correct answers.

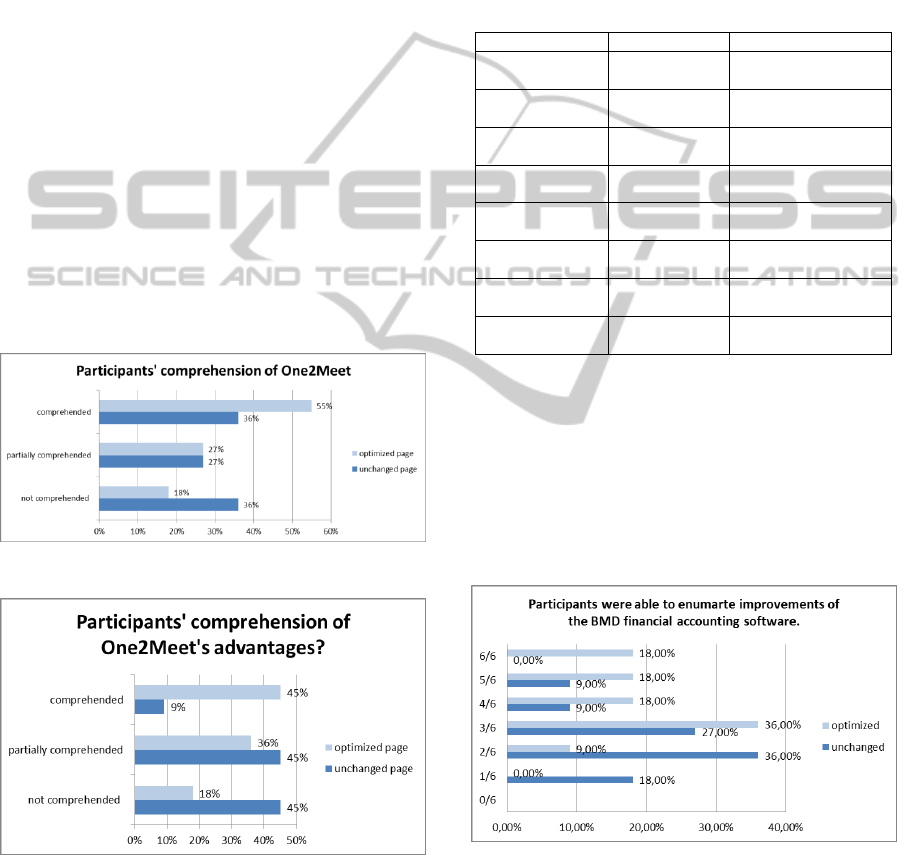

As shown in the previous evaluations, pages that

are optimized according to SEO-measures are

clearly more likely to convey information than

unimproved pages. To further refine and confirm

this finding test, subjects were asked to evaluate the

attainment of the characteristics of presented

information as defined in ISO 9241-12 (ISO 9241-

12:1998: Presentation of information, 1998). The

evaluation was based on the grading system used in

Austrian schools (1 = very good, 2 = good; 3 =

satisfying, 4 = sufficient, 5 = insufficient). The

following chart (figure 7) summarizes the scenario-

specific results and compares optimized and

unchanged page versions:

Figure 7: Evaluation of information presentation.

As figure 7 clearly shows, optimized pages were

significantly better marked (average mark: 2,2) than

unchanged, original page versions (average mark:

3,6).

Hence, optimized website are not only more

adequate to convey information, but are also

perceived as considerably better in terms of

information presentation.

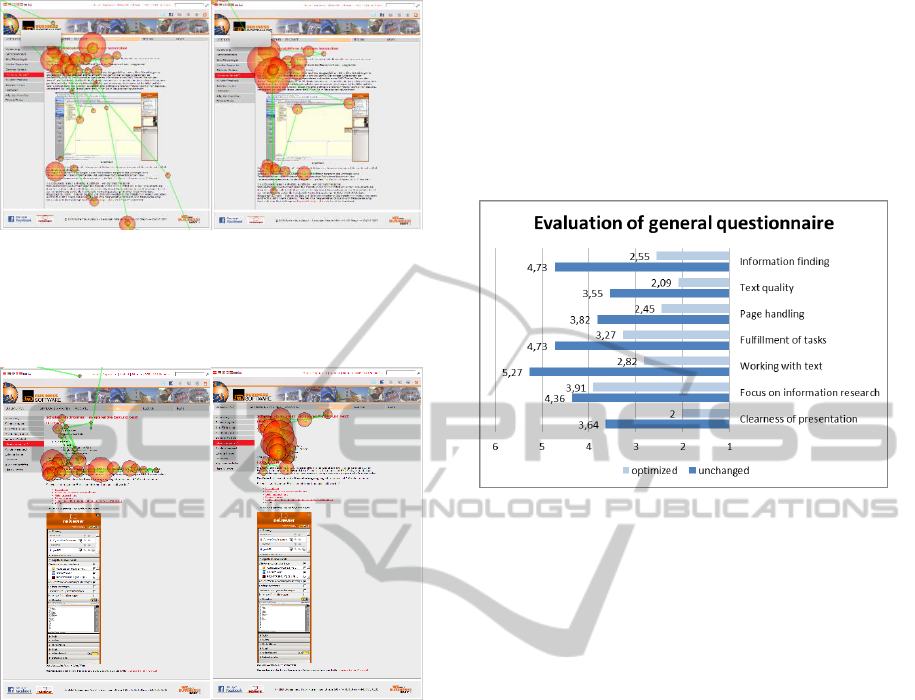

5.2.2 Eye Tracking Analysis Results

The eye tracking analysis was an important part of

the conducted usability evaluation study and allowed

drawing inferences from recorded saccades and

fixations about user behaviour. Thus, it was possible

to analyse which parts of a webpage were looked at

for how long, which, in turn, gave indication of the

way the presented content was perceived.

The following comparison of heat-maps from an

optimized and an unchanged page clearly shows

why optimized pages are better in terms of

conveying information and information presentation:

Figure 8: Heat-map comparison of an unchanged (left) and

optimized (right) page.

Figure 8 visualizes that the test subjects’ focus when

looking at the unchanged page is limited to the upper

third. That means that more than half of the page

was not part of the user focus and the possibility of

information placed there being conveyed was low.

The heat-map of the optimized page on the other

hand had a much broader focus area: especially lists

and headings were focussed. Hence, content was

much more likely to be conveyed.

Eye movement analyses also showed why

optimized pages are more likely to convey content

than unoptimized ones. To visualize this, the first ten

seconds of eye movement of the test subjects from

group A and B - each of scenario one - are

compared. The following figure clearly shows that it

was pretty hard for subject group A to identify

relevant page areas in the early seconds:

Search Engine Optimization Meets e-Business - A Theory-based Evaluation: Findability and Usability as Key Success

Factors

247

Figure 9: Eye movement on unchanged page (group A).

Subject group B on the other hand had a much

narrower focus and was able to identify relevant

content right from the start:

Figure 10: Eye movement on optimized page (group B).

Summarizing, eye tracking results confirm the

findings of the scenario-specific questionnaire and

clearly show that SEO-methods positively influence

websites in terms of information conveyance and

presentation.

5.2.3 Evaluation of General Questionnaires

As previously mentioned, in addition to the

scenario-specific questionnaire, a questionnaire

containing general questions was handed out after

the subject groups had completed the four scenarios.

Test subjects had to evaluate the following seven

questions based on a seven-level grading system,

whereby 1 stood for very easy respectively very

satisfied and 7 stood for not easy at all respectively

not satisfied at all:

How clear was the site presentation?

How difficult was it to focus on information

research?

How easy was it to work with the text?

How fast could you finish your task?

How would you describe page handling?

How satisfied were you in terms of text

quality?

How easy was it to find information?

The following chart visualizes the results of this

questionnaire and compares optimized and

unchanged page versions:

Figure 11: Evaluation of general questionnaire results.

Hence, not only the applied scenario-specific

questionnaires, but also the general questionnaire

clearly shows that optimized pages are perceived as

more usable in terms of information finding, page

handling, text quality, clearness of presentation and

pleasantness of working with them.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Usability and Findability are two key factors for

every website and can make the difference between

success and failure. Hence, not only usability

measures but also SEO-methods should be applied

to improve a website’s overall performance.

In the course of this study, a range of theory-

based usability requirements and recommendations

as well as SEO-standards and methods were

introduced in a first step. In a second step, SEO-

methods, presented in section three, were assigned to

the web usability guidelines and its effects described

in section two. Thereby, it could be ascertained that

these two areas are closely connected, and SEO-

methods positively influence website usability.

By conducting a theory-driven usability

evaluation study the effects of SEO-methods on

website usability could be further analysed.

Hence, the main findings of this paper are:

SEO-methods positively influence website

usability and potential SEO-problems also

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

248

have negative effects on usability.

Decisive contradictions between SEO-

methods and usability could not be found.

The usability evaluation study conducted

clearly showed that SEO-methods improve

effectiveness and efficiency of task

accomplishment.

Websites optimized according to SEO-

methods are perceived as more usable in terms

of information presentation, information

conveyance and user satisfaction.

In conclusion, the theory-based findings could be

confirmed by the results of the usability evaluation

study conducted and a positive correlation between

search engine optimization and website usability

could be found.

REFERENCES

Alby, T., Karzauninkat, S., 2007.

Suchmaschinenoptimierung – Professionelles Website-

Marketing für besseres Ranking, Carl Hanser Verlag,

München, 2

nd

edition.

Arndt, H., 2006. Integrierte Informationsarchitektur – Die

erfolgreiche Konzeption professioneller Websites,

Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg, 1

st

edition.

Auinger, A./Aistleithner, A./Kindermann, H./Holzinger,

A, 2011. Conformity with User Expectations on the

Web: Are There Cultural Differences for Design

Principles? Proceedings of HCII 2011, Springer LNCS

Balzert, H., Klug, U., Pampuch, A., 2009. Webdesign &

Web-Usability, W3L-Verlag, Herdecke, 2

nd

edition.

Baeza-Yates, R., Boldi, P., Bozzon, A., Brambilla, M.,

Ceri, S. & Pasi, G. (2011) Trends in Search

Interaction. In: Ceri, S. & Brambilla, M. (Eds.) Search

Computing, Lecture Notes in Computer Science

LNCS 6585. Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer.

Bischopinck, Y., Ceyp, M., 2009. Suchmaschinen-

Marketing – Konzepte, Umsetzung und Controlling für

SEO und SEM, Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg, 2

nd

edition.

Bloice, M. D., Kreuzthaler, M., Simonic, K.-M. &

Holzinger, A. (2010) On the Paradigm Shift of Search

on Mobile Devices: Some Remarks on User Habits.

Lecture Notes in Computer Science, LNCS 6389.

Berlin, Heidelberg, New York Springer, 493-496.

Bornemann-Jeske, B., 2005. Barrierefreies Webdesign

zwischen Webstandards und Universellem Design. In

Information – Wissenschaft & Praxis. DGI e.V.

Broschart, S., 2010. Suchmaschinenoptimierung &

Usability – Website-Ranking und Nutzerfreundlichkeit

verbessern, Franzis Verlag, Poing, 1

st

edition.

Carl, D., 2006. Praxiswissen AJAX, O’Reilly, Köln, 2

nd

edition.

Cappel, J., Huang, Z., 2007. A Usability Analysis of

Company Websites. In Journal of Computer

Information Systems, International Association for

Computer Information Systems.

Chen, C. Y., Shih, B. Y., Chen, Z. S. & Chen, T. H.

(2011) The exploration of internet marketing strategy

by search engine optimization: A critical review and

comparison. African Journal of Business Management,

5, 12, 4644-4649.

Diaper, D. (2002) Task scenarios and thought. Interacting

with Computers, 14, 5, 629-638.

Erlhofer, S., 2011. Suchmaschinen-Optimierung – Das

umfassende Handbuch, Galileo Computing, Bonn, 2nd

edition.

Fischer, M., 2009. Web Boosting 2.0, Redline,

Heidelberg, 2nd edition.

Gould, J. D. (1991) Making usable, useful, productivity-

enhancing computer applications. Communications of

the ACM, 34, 1, 74-85.

Holzinger, A. (2005) Usability engineering methods for

software developers. Communications of the ACM,

48, 1, 71-74.

Holzinger, A., Mayr, S., Slany, W. & Debevc, M. (2010).

The influence of AJAX on Web Usability. ICE-B

2010 - ICETE The International Joint Conference on

e-Business and Telecommunications, Athens (Greece),

INSTIC IEEE, 124-127.

Hearst, M. (2009) Search User Interfaces. Cambridge,

Cambrige University Press.

Herendy, C. (2009) How to Research People's First

Impressions of Websites? Eye-Tracking as a Usability

Inspection Method and Online Focus Group Research.

In: Godart, C., Gronau, N., Sharma, S. & Canals, G.

(Eds.) Software Services for E-Business and E-

Society. Berlin, Springer-Verlag Berlin, 287-300.

Jacobsen, J., 2005. Website-Konzeption – Erfolgreiche

Web- und Multimedia-Anwendungen entwickeln,

Addison-Wesley, München, 3rd edition.

Krug, S., 2005. Don’t make me think!, New Riders,

Berkeley, 2

nd

edition.

IAB Switzerland, 2010. Suchmaschinenoptimierung –

Ranking-Kriterien 2012, http://www.iabschweiz.ch/

tl_files/iab_schweiz/pdf/IAB-Ranking-Kriterien-201

0.pdf.

International Organization for Standardization, 1998.

Ergonomics of human-system interaction - Part 12:

Presentation of Information (ISO 9241-12:1998).

International Organization for Standardization, 2006.

Ergonomics of human-system interaction - Part 110:

Dialogue principles (ISO 9241-110:2006). http://

www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue

_detail.htm?csnumber=38009.

Kaspring, B. 2011. Online Vermarkter Kreis Report

2011/01.AGOF and OVK. http://www.ovk.de/

fileadmin/downloads/fachgruppen/Online-Vermark

terkreis/OVK_Online-Report/OVK_Online-Report

_2011-01.pdf

Lammenett, E., 2009. Praxiswissen Online Marketing,

Gabler, Wiesbaden, 2nd edition.

Leavitt, M., Shneiderman, B., 2006. Research Based Web-

Design & Usability-Guidelines. http://www.usability.

gov/guidelines/guidelines_book.pdf.

Lynch, P., Horton, S., 2008. Web Style Guide – Basic

Search Engine Optimization Meets e-Business - A Theory-based Evaluation: Findability and Usability as Key Success

Factors

249

Design Principles for creating Websites, Yale

University Press, New Haven/London, 3rd edition.

Malaga, R. A. (2008) Worst Practices in Search Engine

Optimization. Communications of the ACM, 51, 12,

147-150.

Manhartsberger, M., Musil, S., 2001. Web Usability – Das

Prinzip des Vertrauens, Galileo Press, Bonn, 1st

edition.

McRoberts,B., Terhanian, G.H., 2008. Digital influence

Index Study, Harris Interactive, http://www.harris

interactive.de/pubs/Digital_Influence_Index_Whitepa

per_DE.pdf

Nielsen, J., 1993. Usability Engineering, Academic Press,

San Diego, 1st edition.

Nielsen J., Morkes, J., 1998. Applying Writing Guidelines

to Web Pages. http://www.useit.com/papers/webwri

ting/rewriting.html.

Nielsen, J., 2000. Designing Web Usability, New Riders

Publishing, Berkeley, 1st edition.

Nielsen, J., 2001. Designing Web Usability,

Markt+Technik Verlag, München, 2001, 2nd edition.

Nielsen, J., Tahir, M., 2001. Homepage Usability – 50

Websites Deconstructed, New Riders Publishing,

Indianapolis, 1st edition.

Nielsen, J., Loranger, H., 2006. Prioritizing Web Usability,

New Riders, Berkeley, 1

st

edition.

Stickel, C., Ebner, M. and Holzinger, A. (2010) The

XAOS Metric: Understanding Visual Complexity as

measure of usability. Lecture Notes in Computer

Science (LNCS 6389). Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer.

Wenz, C., 2007. JavaScript und Ajax – das umfassende

Handbuch, Galileo Press, Bonn, 7th edition.

White, B. (2003). Web accessibility, mobility and

findability. Web Congress, IEEE, 239-240.

ICE-B 2012 - International Conference on e-Business

250