Accelerating Health Service and Data Capturing Trough Community

Health Workers in Rural Ethiopia

A Pre-requisite to Progress

Zufan Abera Damtew

University of Oslo, Informatics Department, Oslo, Norway

Keywords: Community Health Workers, Health Extension Package, Health Data, Knowledge Boundaries,

Communication, Brokering.

Abstract: Community based health service is escalating in many developing countries as a means to fulfill health

related millennium development goals. Community health workers provide primary health care, and collect

and compile health data in collaboration with different actors. This collaboration requires knowledge

communication. An interpretative case study was conducted in Ethiopia to understand the knowledge

communication across boundaries. Using transfer, translation and transformation framework of Carlile, this

study discuss how knowledge related to the health extension packages is communicated across syntactic,

semantic and pragmatic boundaries among health extension workers, their teachers, supervisors, community

volunteers and rural households. The study also describes the knowledge brokering role of health extension

workers and voluntary community health workers. They interact and negotiate with rural households to

facilitate communication of novel knowledge concerning the health extension packages. The study

identified impediments that preclude knowledge communication. In order to improve knowledge

communication across boundaries and enhance the implementation of health extension packages, it is

essential; to formulate apt target for health services, equip health extension workers training schools with

essential resources, offer trainings to community volunteers and make available standardized register and

report formats at health posts for proper recording and reporting.

1 INTRODUCTION

Community health workers are best positioned to

deliver health services at grass-root level as

countries around the globe strive to meet the

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) (WHO

and Global Health Workforce Alliance, 2010). In

addition to health care provision, community health

workers are also playing an important role in

capturing and communicating the community health

data (Otieno, 2012). Information that is available in

most developing countries is derived from health

facilities, yet most illness and death occur outside

the health system. Presently, community health

workers are providing primary health care and

collect health status data at the community and

household level that helps for informed decisions

(ibid). Community health workers have been used to

collect health related data in many countries that

increases the health coverage, for example,

achieving high rates of case detection for

Tuberculosis in Bangladesh (Chowdhury et al,

2009). Although it is emerging, computerization of

HIS at all levels in the health care system of most

developing countries seems intricate with the

existing infrastructure and human resources. Thus,

data from the community service sites and primary

health care units are currently gathered manually.

This paper draws on empirical findings from

Ethiopia, a country striving to improve the health

service access and data capturing through salaried

community based health workers called health

extension workers (HEWs).

In Ethiopia, health extension program is

designed to improve the health status of families,

with their full participation, using community’s skill

and wisdom (FMOH, 2005). The main pillars for the

health extension program are HEWs. Their primary

role is to perform preventive health education to

households in their homes. Through close

interactions, HEWs improve the implementation of

innovative health extension packages by rural

168

Abera Damtew Z..

Accelerating Health Service and Data Capturing Trough Community Health Workers in Rural Ethiopia - A Pre-requisite to Progress.

DOI: 10.5220/0004135101680177

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2012), pages 168-177

ISBN: 978-989-8565-31-0

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

dwellers. HEWs are supported by trained body of

voluntary community health workers (VCHWs),

who are members of a given community and they

volunteer to support HEWs.

Health care is a dynamic discipline whereby new

procedures, practices and treatments are introduced

very often, which demand in-service training,

mentoring and knowledge communication.

Nevertheless, providing in-service training for entire

HEWs will not be an easy for resource constraint

country like Ethiopia. Studies also indicated that

knowledge communication among the public health

actors is a challenging process. For instance, a study

conducted with the premise of target setting

procedure for immunization service in Ethiopia has

showed the gap between target given for health

services from districts to health posts (HEWs) and

head counted population by HEWs (Damtew and

Kaabøll, 2011). This gap created confusion and lack

of common understanding between HEWs and the

health authorities. The effort to scale-up the

innovative health extension packages requires close

interaction and negotiation between HEWs and rural

households. Moreover HEWs interact with their

colleagues, supervisors, VCHWs and traditional

birth attendants (TBAs) that require knowledge

communication.

In this study, the knowledge transfer, translation

and transformation (the 3-T) framework by Carilie

(2002; 2004) was used to understand the knowledge

communication across boundaries in day-to-day

practices of community health workers. In this

framework the author revealed that communicating

knowledge across three progressively complex types

of boundaries— syntactic (structure), semantic

(meaning), and pragmatic (practice) — requires

different processes that include transfer, translation

and transformation. In this framework, four

characteristics, which facilitate effective boundary

process and knowledge communication, are

specified. These characteristics include---establishes

a shared language; provides a concrete means of

specifying differences and dependencies; facilitates

the way for jointly transformation of knowledge and

enable multiple interactions. This framework helps

to analyze the knowledge communication process

across boundaries in the public health sector. In this

case, knowledge communication or sharing refers to

the way HEWs along with their teachers,

supervisors, colleagues, VCHWs, TBAs, and the

community transfer, translate and transform their

knowledge while performing their day-to-day

activities.

Different researchers also mentioned that

knowledge brokering can contribute to innovation

and knowledge communication (Hargadon, 2003;

Howells, 2006) and it is effective in improving the

service quality and decision making (Dobbins et al.,

2009). Brokering involves process of translation,

coordination, and alignment between perspectives

and it promotes interaction. The role of knowledge

brokers as intermediaries is widely documented.

The broker is constantly seeking knowledge

opportunities in his/her immediate environment,

capable of introducing promising new innovations

(ibid). Brokering knowledge thus means far more

than simply moving knowledge—it also means

transforming knowledge (Myer, 2010). Knowledge

brokering tends to happen in particular locations—in

spaces that privilege the brokering of knowledge

across boundaries. For instance,

Ward, V., House

(2009) indicated that individuals were employed to

act as “knowledge brokers” and their job was to

facilitate the transfer of knowledge between

researchers and practitioners in order to improve the

health outcomes. Within the same vein, this research

identifies the role of HEWs and VCHWs as

knowledge brokers in the expansion of the

innovative health extension packages.

This research addresses the following two

questions; what is the role of HEWs and VCHWs as

knowledge brokers to facilitate the implementation

of the innovative health extension packages by rural

households? And, how can knowledge

communications regarding the health extension

packages is facilitated across boundaries?

A qualitative case study through observation,

interviews, focus group discussion and document

analysis was conducted to answer the research

questions.

The rest of the paper is organized as follow. In

section two, I briefly discuss the literature reviewed.

In section three, I provide background of the

research context. This chapter also summarizes the

research methods adopted for the data collection and

analysis. Thereafter, in section four, the findings

will be presented. I then provide the discussion and

conclusion of the study in section five.

2 LITRATURE REVIEW

2.1 Knowledge Boundary and

Communication

This paper deals with the notion of knowledge

communication across boundaries between

communities. These communities consist of public

AcceleratingHealthServiceandDataCapturingTroughCommunityHealthWorkersinRuralEthiopia-APre-requisiteto

Progress

169

health actors from different specialized domain that

include HEWs, VCHWs, traditional birth attendants

(TBAs), health managers and rural dwellers.

According to Carlile (2004: 2002), the difference in

the knowledge domain, dependence (the degree to

which people take each other’s views into account to

meet their goals) and novelty of domain-specific

knowledge among people at the boundary determine

the complexity of communicating knowledge.

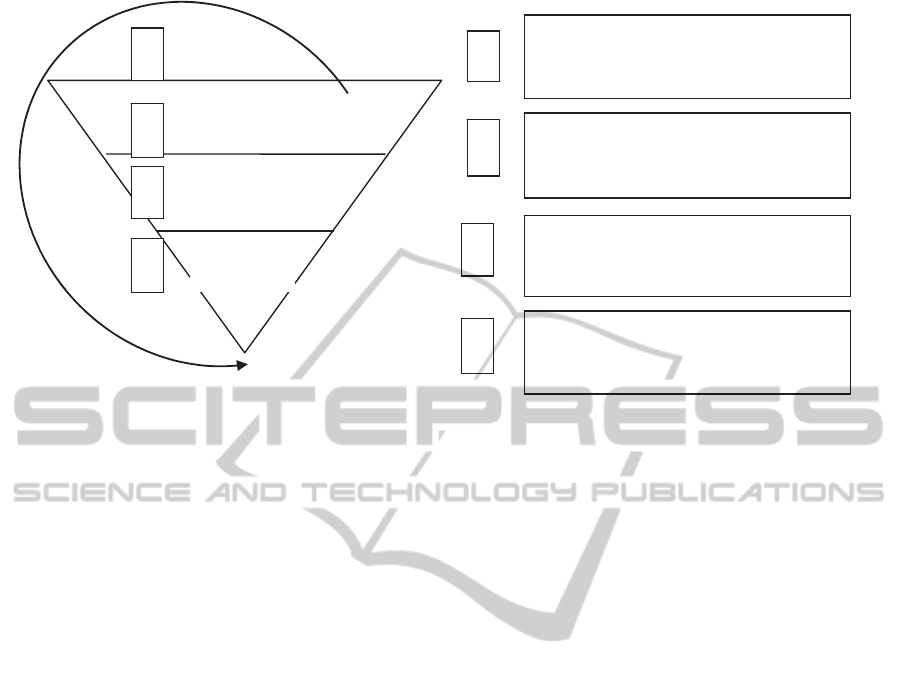

Carlile (2004) used an inverted triangle to show how

increases in the difference, dependence, and novelty

of knowledge between people create three

progressively complex boundaries— syntactic,

semantic and pragmatic (See figure1).

As shown in figure1, tip of the inverted triangle

represents situations where the syntax/language is

shared and sufficient, so knowledge can be

transferred across the boundary. Knowledge transfer

focuses on one-way movements of knowledge or

learning from one place to another or from sender to

receiver (Argote, 1999; Szulanski, 1996). The major

challenge of knowledge transfer is using a

communication medium that is capable of

transmitting the richness of the information to be

conveyed (Daferdst and Lengel, 1984). However, as

novelty increases and the gap grow, new differences

and dependencies arise that requires a semantic

boundary and translation to create new agreements.

This necessitates conversation or discourse to share

knowledge between actors. Discourse is needed to

create shared meanings as way to address the

interpretive differences among actors (Carlile, 2004;

2002). Through collaboration, the participants

produce common meanings and coordinate local

agreement, for instance when co-authors of a paper

simultaneously construct meanings of their work and

make sense of their interaction.

On the other hand, under conditions of

conflicting interests, creating common meanings

(translation) may not be possible: what is required is

a process in which participants negotiate and are

willing to transform their own knowledge and

interests to fit a collective domain (ibid). A

pragmatic boundary assumes the conditions of

difference, dependence and novelty are all present,

and requires transforming the existing knowledge.

Differing background and interest of

stakeholders who are commonly engaged in similar

work may face complex (pragmatic) boundaries to

communicate their knowledge that require multiple

iterations. This is why the knowledge a group

currently uses is such a problematic anchor point

when novelty arises across the knowledge boundary.

Carlile, (2002; 2004) also identified four

characteristics (see Figure1), which facilitate

effective boundary process that include: 1)

establishes a shared language to represent

knowledge; 2) provides a concrete means of

specifying differences and dependencies; 3)

facilitates a method in which individuals can jointly

transform the knowledge used and 4) the need of

multiple interactions. He stated that different

combinations of characteristics of a boundary

process are required depending on the type of

boundary faced.

If a syntactical boundary is faced, only

characteristics 1 and 4 are necessary because it is a

matter of transferring knowledge through a given

syntax. At a semantic boundary, characteristics 1, 2

and 4 are necessary. Here, with some shared syntax

and a negotiation on the differences and

dependencies, new agreements can be created to

reconcile the discrepancies. At a pragmatic

boundary, characteristics 1, 2, 3 and 4 are necessary.

The current and novel forms of knowledge have to

be jointly transformed to create new knowledge.

Hence, communicating at more complex boundaries

requires the capacity below them. For example,

knowledge translation assumes knowledge transfer,

and knowledge transformation also requires

knowledge transfer and knowledge translation

processes.

2.2 Knowledge Brokering

Knowledge brokers can facilitate the knowledge

communication by identifying, synthesizing and

adapting knowledge for the potential users (Meyer,

2010). Sverrisson (2001) also mentioned that

knowledge brokers can be individuals or

organizations that facilitate the creation, sharing, and

use of knowledge. An important task for the broker

is to foster the conditions where the level of

acceptance for any action is considerably higher than

the level of resistance (Jackson, 2003). This may

requires much iteration undertaken over a substantial

period of time.

According to Meyer (2010), brokering involves a

range of different practices: the identification and

localization of knowledge, the redistribution and

dissemination of knowledge, and transformation of

this knowledge.

The role of knowledge brokers as intermediaries

to facilitate knowledge communication is not new

(Hargadon, 2003). Over time, this role of knowledge

brokers has diversified and has often been adapted to

different contexts including the health sector (van

Kammen, et al., 2006). The authors discussed the

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

170

Pragmatic

Semantic

Syntactic

1

2

3

4

1

2

3

4

Supportsaniterativeapproachwhere

individualsgetbetteratrepresenting,

specifyingandtransformingknowledge.

Allowsindividualstonegotiate,validateand

transformtheirknowledgeinorderto

createnewknowled

g

e

.

Provide individualsaconcretemeanso

f

specifyingtheirdifferences

and

dependencies.

Establish somesharedlanguage/syntaxfor

representingeachother’sknowledge.

Figure1: 3-T Framework and the four characteristics of a “Boundary Process”, adapted from Carlile (2004: 563).

importance of knowledge brokering to develop

evidence based health policy. In this context, we

want to explore the intermediaries (knowledge

brokering) role of HEWs and VCHWs between the

source of knowledge (the health extension package)

and users of knowledge (the rural community) that

may facilitate expansion of the innovative health

extension activities.

3 RESEARCH CONTEXT AND

METHODS

3.1 Research Setting

The case study site presented in this paper is based

in Ethiopia, a developing country located in the horn

of Africa. Organizational structure of the health care

system of Ethiopia comprises four tiers, primary,

secondary and tertiary levels of health care. The first

two tiers are the primary health care units consist of

health posts where HEWs are deployed and health

centers that provide basic curative services. The

health extension program in Ethiopia, which this

study is focused on, was introduced in 2004.

Accordingly, each household is expected to

implement sixteen health packages, which could be

broadly categorized into four areas--environmental

sanitation and hygiene promotion, family health,

major diseases prevention and control, and health

education and communication (FMOH, 2005). Two

HEWs are mostly responsible for a community with

about 5,000 populations where about 20 VCHWs

also work in cooperation with HEWs. Households

are motivated to practice health extension packages

that may lead them to healthy living. According to

the HEP national guideline, households graduate

within six month after implementing 75% of the

sixteen health extension packages.

3.2 Methods

This study employed an interpretive case study

approach (Walsham, 2006) with the use of

interviews, observations, document analysis and

focus group discussion. We have also attended the

primary health care unit meeting in one health

center. “Case studies emphasize detailed contextual

analysis of a limited number of events or conditions

and their relationships” (Soy, 2006). A case study

was chosen because this approach brings about an

understanding of a complex issue hence provide

insights in investigating the cooperation and

knowledge communication in day-to-day practice of

public health actors.

The empirical materials presented in this study

were collected during the periods from December

2009 to February 2010 and from June to July 2011.

Data gathering was carried out at two HEWs

training schools, Amhara region health Bureau, two

zonal health departments, four district health offices,

and eight health posts. Data were collected by the

author and informed consent was sought from each

study participant. Interviews were conducted with

four HEWs’ teachers, nine health managers at

regional, zonal and district health offices and 12

HEWs. We also conducted focus group discussions

AcceleratingHealthServiceandDataCapturingTroughCommunityHealthWorkersinRuralEthiopia-APre-requisiteto

Progress

171

with HEWs and VCHWs in three villages where

each group consisted of five to six participants.

Observation helped to get first hand information

about the organization of rural health posts, the tools

that HEWs using including the registers and health

communication support materials. Document

analysis was done on various sources such as,

working manuscripts, HEWs field note-books and

official registers and formats used to collect,

analyze, and transmit data.

A research diary was maintained throughout the

data collection to document interview notes,

observations and ideas raised during the meeting and

focus group discussions. Notes taken during data

collection were transcribed at the end of the day.

The data analysis was interpretative through

triangulating data from different sources and some

notes were cross-checked with respective

respondents. Theoretical concepts that include

knowledge boundary, communication and brokering

were used to analyze the empirical data. A list of

themes were constructed from the data and presented

in the finding section as follow;

4 CASE DESCRITION

4.1 The Role of HEWs and VCHWs in

Health Service Provision and Data

Management

More than 34,000 female HEWs are deployed in

rural Ethiopia. They are mainly engaged in creating

health awareness and support communities to

practice health actions. According to the national

guideline of the health extension program, HEWs

are supposed to spend 70-75% of their working time

on home based and outreach health services

provision modalities (FMOH, 2005). This was also

confirmed by interviewed HEWs as follow: “We

stay at health posts in the morning and

evening…during the day time we go to home visiting

and outreach”. Two HEWs are assigned in most

visited villages thereby they divided their catchment

area into two and conduct their activities. When the

number of population exceeds 7500 in a specific

village, the district health office deploys three to

four HEWs.

Interviewed HEWs noted that, there are VCHWs

in each village (Got) who usually help them for their

duties. As they are working at health post, household

and outreach level, HEWs are mostly over stretched

in scattered settlement hence they appreciated the

help of VCHWs. At the beginning of their job

assignment, HEWs collected the baseline health data

from their respective catchment villages and

prepared map of their localities. In the visited health

posts, they have collected data with the help of

VCHWs. HEWs, on the other hand, offer formal and

informal trainings for VCHWs. They do have

monthly meetings, as well as, informal gatherings,

which were found to be good media for knowledge

sharing. Besides, some HEWs also share experience

with TBAs and develop their skill related to

managing normal delivery. TBAs give delivery

service as most births occur at home in rural

Ethiopia. Some HEWs have gained skill on how to

assist delivery with the help of TBAs. However,

some TBAs were not interested in establishing close

contact with HEWs.

While conducting home visiting, HEWs hold

some essential equipments and supplies including

their ordinary register book which they call “field

note-book”. HEWs use their field notes for two

purposes; for follow-up of the implementation of

health extension packages by households and to

copy the data captured in the field to a main register

for reporting. While providing health services, they

record in the field note-book the services they

provided, next appointment date and health actions

to be performed for the next visit. Afterwards,

during the following visit, they check whether

households perform the health extension packages

based on the given advice. HEWs gather and

compile the community health data continuously.

The main registers serve for data recording and

preparing monthly and quarterly reports. However,

these registers are not standardized thus the data

collected across health posts were not consistent

and

there is redundancy of data elements. HEWs, even

within the same district, use different types of

formats for reporting that sometimes affect

comparison of health facilities performances and

constrain experience sharing. With the compiled

data, HEWs prepare minimum wall charts with key

health targets and indicators and post them on walls

of the health posts. They usually use the data to

monitor the progress of their services and one can

easily look at the profile of their catchment areas at

health posts. HEWs discuss with the VCHWs on the

monthly performance report and design strategies to

improve the health service coverage.

In practice, there are two population data source

for the health sector at lower level. One is the

official number of population projected based on the

national census and the second is head counted by

HEWs and VCHWs in their catchment area. In line

with Damtew and Kaasbøll (2011), the findings of

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

172

this study show that the target for health services

given to health posts from the districts is mostly

different and higher than head counted population by

HEWs and VCHWs. In some visited villages,

however, HEWs and their supervisors made effort to

resolve the ambiguity created by the discrepancy

between the official target and head counted

population. They rather follow the notion such as

“There should be not unvaccinated infant, no

household without pit latrine, and so forth.” than

being overwhelmed by the inflated target given from

district authorities. For instance, to ensure that every

child is vaccinated, HEWs and VCHWs search for

defaulters in their vicinity and their supervisors also

conduct random revisits in selected villages.

4.2 Knowledge Sharing Mechanisms

4.2.1 The Input from Pre-service Training of

HEWs

The pre-service training provides basic knowledge

for HEWs which helped them to perform their tasks.

For example, community health documentation is

one course given during pre-service training.

Interviewed HEWs mentioned that this course

helped them to sketch village maps manually, and to

collect and analyze health data. However, in the

HEWs training institutions, the proportion of

trainees was higher compared to the number of

teachers and teaching facilities that challenged the

teaching learning process. Scarcity of supplies, such

as demonstration materials and standardized data

collection tools, and inadequate practical sessions

compromised the quality of pre-service training.

Lecturing was the main method of instruction in

HEWs training schools, where the role of teachers

was offering lecture to trainees. The language barrier

was highlighted as a hindrance for transferring

knowledge. HEW teachers mentioned that the

instructional media is English and most HEWs

appeared to lack English language proficiency that

preclude them from being fully engaged. Moreover,

all books in HEWs training schools library, as well

as, some training, and recording and reporting

formats were prepared in English. This caused

difficulties to HEWs to absorb them effectively.

Interviewed HEWs also commented that the pre-

service training does not equip them effectively to

implement tasks included in the health extension

packages.

4.2.2 Knowledge Sharing among Peers

Some additional tasks are shifted to health posts

(HEWs) recently that require additional on-the-job

trainings. The FMOH with support from partners has

tried to organize and offer complimentary on-the-job

trainings for HEWs, such as “clean delivery training

and integrated refresher training”. Clean delivery

training is provided for one month. It is skill based

training, which enables HEWs to manage normal

delivery, recognize danger signs for early referral

and to capture the required information across the

continuum of care. They get training at relatively

well-equipped health centers and district hospitals,

which have better set up compared to rural health

posts. For instance, health centers have ready-made

register books for delivery, albeit HEWs are

supposed to modify bare exercise books, draw lines

and write titles to prepare delivery register books.

According to our observation, the maternity rooms

of rural health posts are also ill-equipped. Integrated

refresher training, on the other hand, includes all

tasks supposed to be performed by HEWs. It is

comprehensive training given for one month in three

phases. There are also other on-the-job trainings for

HEWs organized by the health sector and other

stakeholders, especially when the new health service

is initiated at the health post level.

HEWs and their supervisors noted that mostly

one of the two HEWs from the same health post

attends on-the-job trainings alternatively. Then the

other one share the knowledge from her friend. In

six of the visited health posts, one of the two HEWs

working in the same health post trained on providing

clean delivery. The training helps them to offer

delivery service and register births as ascertained by

the following quote; “After I received clean delivery

training, I can able to identify high risk mothers,

manage delivery, give newborn and postpartum

care, and register data properly. I also showed the

procedure to my colleague. We adapted the delivery

register and record all the required information.”

HEW who received in-service clean delivery

training.

Similarly HEW at one of the visited health posts

who was not trained on prevention of mother to

child transmission of HIV/AIDS said; I did not

receive formal in-service training on HIV testing.

However, I learned from my colleague who had

training and currently I am offering the service in

her absence.

In most visited health posts, the two HEWs work

together and interact closely, which created an

opportunity for knowledge sharing. They mentioned

that they keep materials which were provided from

trainings in their health post and use them jointly.

HEWs stated that they meet on monthly bases at the

AcceleratingHealthServiceandDataCapturingTroughCommunityHealthWorkersinRuralEthiopia-APre-requisiteto

Progress

173

nearest health center with their workmates from

neighboring health posts and health center (primary

health care unit meeting) and they discuss their

monthly performances, constraints and future

actions to improve performance based on the service

statistics. In some health centers, they organize the

meeting with special coffee ceremony that may

strengthen the social bond among staff and trigger

informal discussion that promote knowledge sharing

(see picture1).

Picture 1: Staff meeting with coffee ceremony at Chara

health center.

There is also quarterly performance review

meeting and experience sharing sessions of HEWs

with district health office and health center staffs, as

well as, biannual review meeting with zonal health

office and annual review meeting at the regional and

national level. Other partners may also take part in

those meetings. Experience sharing sessions take

place during these meetings where best performing

districts and HEWs communicate their best practices

with their colleagues that may improve performance

of the health sector. Experience sharing usually

takes place through written reports or oral

presentation that may illustrate knowledge transfer.

Awards also were given for selected HEWs and

districts owing to their good performance. However,

sometimes the ambiguity of target set for health

services cause tense argument to select best

performing health posts and HEWs.

4.2.3 Knowledge Sharing with the

Community: The Role of HEWs and

VCHWs as Knowledge Brokers

In their day-to-day practices, HEWs discuss,

converse and negotiate with households thereby help

them to practice health actions and enjoy healthy

lives. They play a role of knowledge broker by

facilitating knowledge communication between the

rural community and the new initiative by the health

sector (the health extension packages) through

continuous interaction with households. During

home visiting, HEWs acknowledge, praise and

encourage the family that performed the

recommended health activities based on their

suggestions. If the household didn’t perform the

recommended actions, they keep on motivating,

demonstrating and negotiating with the household to

accomplish the intended task for the following visit.

This action is continued until a specific family

practiced at least 75% of the health extension

packages and graduated. HEWs revealed that some

households accept the health advice and guidance

promptly and some may implement the health action

following their friends or neighbors. However, some

households may resist changing thereby continuing

the usual way of doing. Some others, on the other

hand, may revert back and stop executing healthy

practices for themselves and their children. For

instance, an interviewed HEW stated; “There are

families who consider “having many children as an

asset”; it is difficult to convince them to use

contraceptive methods for birth spacing and fertility

control”.

Some other families may yet consider traditional

practices as best for their family health. Hence,

HEWs stressed the importance of continuous

negotiation, and the exemplary role of VCHWs to

bring the requisite progress in health action. The

following excerpts from HEWs illuminate the

intermediary role of VCHWs; When there is a

defaulter client for a health service, we inform a

VCHW then s/he explains the absentee about the

advantage of the service…..converse and negotiate

thereby help the defaulters to resume the service.

There are about 18 VCHWs in our vicinity; their

presence helped most households to implement the

health extension packages.

Sometimes, the health sector and other partners

organize trainings that include VCHWs, thus they

propel clients to seek health service. For instance,

one VCHW during focus group discussion

mentioned “We received training about community

mobilization for HIV counseling and testing service:

afterwards we advise pregnant women in our village

to take voluntary counseling and testing for HIV

before delivery”.

5 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSION

Our findings showed that HEWs provide basic

preventive, promotive and curative health services to

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

174

rural households. Capturing and communicating the

community health data is also one of the major tasks

of HEWs as good health management highly relies

on accurate and relevant information to make health

services responsive to the demands of the

population. Meanwhile, knowledge sharing was

taking place during their day-to-day practices. In the

pre-service trainings of HEWs, the main mode of

instruction was lecture. It was mainly one way of

transferring information from sender to receiver,

which may fosters knowledge transfer according to

Carlile (2004). However, lack of the common syntax

between teachers and HEWs due to a language

barrier and shortage of facilities affected knowledge

transfer process negatively. Lack of discourse

because of the language problem also inhibited the

knowledge translation and transformation processes.

Interviewed HEWs stated that they did not get

sufficient knowledge and skill at their pre-service

training.

On the other hand, the experience sharing

sessions from best performing districts or HEWs to

others can indicate knowledge transfer from sender

to receiver through shared syntax. This resonates

with the knowledge transfer explanations by Argote

(1999) and Szulanski (1996). These authors

explained that knowledge transfer can occur when,

for example, a unit communicates with another unit

about a practice that it has found to improve

performance. Carlile (2004) explained how

transferring knowledge through shared syntax is

unproblematic. In this study, experience sharing

sessions among the health staff were found crucial

for knowledge sharing. The findings of the study

also showed that HEWs and VCHWs discuss,

converse and interpret the meaning of performance

reports thereby create common syntax. They

translate the meaning of performance reports in a

sense making way to their specific situation. HEWs

and their supervisors also make dialogue during

meetings and supportive supervisions, and create

common understanding. For example, to reconcile

the discrepancy created by the difference between

the official target and head counted population by

HEWs and VCHWs, they discussed and created

common syntax such as “there should be not

unvaccinated infant” to ensure every child got

vaccines. This process requires creating new

agreements through dialogue and collaboration

across a semantic boundary.

In their day-to-day practices, the two HEWs

assigned in the same health post interact with each

other thus share knowledge. They bring new

concepts and knowledge from in-service trainings,

and they converse each other and negotiate to create

syntactic, semantic and pragmatic understanding

among themselves. This may require changing of the

knowledge they currently use. For instance, after

taking clean delivery training, HEWs disregarded

the previous register for delivery and prepared new

register based on the new knowledge they acquired

from the training.

According to Carlile (2002), the knowledge a

group currently use may create problem when

novelty arises. In our study, the rural households

may have their own knowledge and ways of doing to

keep their family health, for instance, they may

follow traditional practices. The innovative health

extension package is a new initiative designed by the

health authorities to improve health status of rural

dwellers. The finding of this study showed the

knowledge that households used preclude them to

practice new actions in the health extension

packages. HEWs and households are specialized in

different knowledge domains and they have many

dependencies in completing a task, hence the

boundary is complex (pragmatic). The dependencies

between HEWs and households happen from the

need of their joint input to implement the health

extension packages. HEWs facilitate the

implementation of the health extension packages by

full participation of the rural households. As

(Carlile, 2004; 2002) put it, communicating

knowledge between people with different knowledge

domain and high dependency face pragmatic

boundaries that require close interaction and

negotiating of conflicting interests. Therefore, it was

not easy to transform the existing knowledge of the

rural community to accommodate the new health

initiatives.

In summary this paper has addressed processes

of communicating knowledge related to the health

extension packages and the community health data,

across syntactic, semantic and pragmatic boundaries

among public health actors in the context of a

developing country. From the case description, it

can be concluded that knowledge communication of

HEWs with their teachers, peers, VCHWs, TBAs,

supervisors and the community needed different

processes

. For example, experience sharing sessions

during meetings denoted knowledge transfer through

shared syntax. HEWs made dialogue with VCHWs

and their district supervisors thereby created shared

meanings across semantic boundaries. Pragmatic

boundaries were faced between HEWs and rural

households because of the difference in their domain

specific knowledge and high dependency to

accomplish the task related to the health extension

AcceleratingHealthServiceandDataCapturingTroughCommunityHealthWorkersinRuralEthiopia-APre-requisiteto

Progress

175

packages. This needed close interaction and

negotiation to transform the current knowledge of

rural households.

The findings also showed that some households

slip-back from implementing new ways underlining

the need of further research to identify the reasons to

sustain the required change and improve the health

of the community.

The research questions outlined in the

introduction section are addressed as follow;

1. What is the role of HEWs and VCHWs as

knowledge brokers to facilitate the implementation

of the innovative health extension packages by rural

households?

HEWs continuously communicate the new

knowledge (health extension packages) with

households. They repeatedly converse, negotiate and

renegotiate with households to influence them to

transform their current knowledge and practice.

Their efforts continue until the families accept the

advice and implement the health initiative.

Meanwhile, the undertaking of HEWs to advance

knowledge communication across pragmatic

boundary was intensified by the efforts of VCHWs.

Both HEWs and VCHWs can take the role of

knowledge brokers who are facilitating the

communication and use of knowledge regarding the

health extension packages. As to Sverrisson (2001),

they facilitate knowledge communication and use

between the source of knowledge (health extension

packages) and potential users (rural households).

New health services are introduced to rural Ethiopia

and as novelty increases, the gap at the boundary

grows (Carlile, 2002). Meanwhile, the knowledge

brokering role of HEWs and VCHWs will continue

to close the gap that emerged as a result of novelty.

Theoretically, the study contributes to the 3-T

framework (Carlile, 2002; 2004) by identifying the

role of HEWs and VCHWs as knowledge brokers

that strengthen the four characteristics of a boundary

process: establishes a shared language; provides a

means of specifying differences and dependencies;

facilitates jointly transformation of knowledge and

multiple interactions. The knowledge brokering role

of HEWs and VCHWs was noticeable throughout

the four characteristics of a boundary process. They

make dialogue and multiple interactions with

households thereby help the families to transform

their knowledge and follow the new health

initiatives in the health extension package.

2. How can knowledge communication regarding

the health extension package be facilitated across

boundaries?

The findings of this study have shown the

knowledge communication process across

boundaries in the efforts of expanding the health

extension packages, and capture and compile

community health data. The study also identified

constraints that preclude knowledge communication

across syntactic, semantic and pragmatic boundaries.

For instance, shortage of resources and language

barriers has affected the knowledge transfer process

at HEWs pre-service trainings. The obsolete target

also imposed a challenge on sharing and

multiplication of good experiences during meetings.

The collaboration and social network were also

hindered by lack of confidence and interest as seen

by absence of communication between HEWs and

some TBAs. The following recommendations are

proposed to facilitate the implementation of the

health extension packages and to make the context

more conducive to knowledge communication;

Provide Essential Resources to HEWs Training

Schools; HEWs training schools should be equipped

with essential teaching facilities to facilitate the

teaching-learning process.

Appropriate Target Setting Procedure; there is a

need to follow apt target setting procedure for health

services to increase understanding among the health

staff and other stakeholders.

Availability of Standardized Data Collection

Tools; appropriate supplies and standardized data

collection tools should be made available at health

posts for proper recording and reporting.

Training for Community Volunteers; providing

training to community volunteers (VCHWs and

TBAs) is required for boosting their confidence and

work motivation that increase service coverage.

While the analysis of this study has been drawn

from the findings of the public health sector in

Ethiopia, the study has also broader implication for

other disciplines and contexts where knowledge

sharing is crucial. Therefore, more comprehensive

studies are recommended in different settings to

strengthen the findings of this study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The field work for the study was sponsored by the

Norwegian Research Council to which we are

grateful. We are also grateful to participants of the

study who spent their spare time for the study.

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

176

REFERENCES

Argote, L., 1999. Organizational learning: Creating,

retaining, and transferring knowledge. Norwell, MA:

Kluwer.

Carlile. P. R., 2002. A pragmatic view of knowledge and

boundaries: Boundary objects in new product

development. Organ. Science. 13: 442-445.

Carlile, P. R., 2004. Transferring, translating and

transforming: an integrative framework for managing

knowledge across boundaries. Organization Science.

15. 555-568.

Chowdhury, A., Chowdhury S., Islam M., Islam A.,

Vaughan J., 2009. Control of tuberculosis by

community health workers in Bangladesh. The

Lancet.; 350 (9072):169–172.

Daferdst, R. L., Lengel, R. H., 1984. Information

Richness: A New Approach to Managerial

Information Processing and Organizational Design,

Research in Organization Behavior. Greenwich.

CT:JAI Press, P.6.

Damtew, Z., Kaasbøll, J., 2011. Target Setting procedures

for Immunization Services in Ethiopia: Discrepancies

between Plans and Reality. Journal of Health

Management. 13(1): 39-58.

Dobbins, M., Robeson, P., Ciliska, D., Hanna, S.,

Cameron, R., O'Mara, L., DeCorby, K., Mercer, S.,

2009. A Description of a Knowledge Broker Role

Implemented As Part of a Randomized Controlled

Trial Evaluating Three Knowledge Translation

Strategies. Implementation Science. 4: 23.

Federal Ministry of Health, 2005. Health Sector Strategic

Plan (HSDP-III) 2005/6-2009/10. Ethiopia.

Hargadon, A. B., Ed. 2003. How Breakthroughs Happen,

The Surprising Truth about How Companies Innovate.

Boston, Massachusetts.

Howells, J., 2006. Intermediation and the role of

intermediaries in innovation. Research Policy. 35(5):

715.

Jackson, N., 2003. Introduction to brokering in higher

education. In N. Jackson (Ed.), Engaging and

changing higher education through brokerage.

Aldershot , UK: Ashgate.

Meyer, M., 2010. The Rise of the Knowledge Broker.

Science Communication. 32: 118-127.

Otieno, C. F., Kaseje, D., Ochieng, B. M., Githae, MN.,

2012. Reliability of Community Health Worker

Collected Data for Planning and Policy in a Peri-

Urban Area of Kisumu, Kenya. J. Community Health.

37(1): 48-53.

Soy, S. K., 2006. The Case Study as a Research Method,

http://www.gslis.utexas.edu /~ssoy uses

users/l391d1b.htm “accessed on 01/03/2010”.

Sverrisson, A., 2001. Translation networks, knowledge

brokers and novelty construction: pragmatic

environmentalism in Sweden. Acta Sociologica. 44:

313-327.

Szulanski, G., 1996. Exploring external stickiness:

Impediments to the transfer of best practice within the

firm. Strategic Management Journal. 17: 27-43.

van Kammen, J., de Savigny, D., Sewankambo, N., 2006.

Using Knowledge Brokering to Promote Evidence-

Based Policy Making: the Need for Support Structure.

Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 84: 608-

612.

Walsham, G., 2006. Doing Interpretive Research.

European Journal of Information Systems. 15: 320-

330.

Ward, V., House, A., and Hamer, S., 2009. Knowledge

Brokering: The Missing Link in the Evidence to

Action Chain? Evidence and Policy: A Journal of

Research.

Ziam, S., Landry, R., and Amara, N., 2009. Knowledge

Brokers: a Winning Strategy for Improving

Knowledge Transfer and Use in the Field of Health.

International Review of Business Papers 5: 491-505.

AcceleratingHealthServiceandDataCapturingTroughCommunityHealthWorkersinRuralEthiopia-APre-requisiteto

Progress

177