Modeling Dynamic Behavior of Business Organisations

Extension of BPM with Norms

Kecheng Liu, Majed Al-rajhi, Anas R. Alsoud, Lawrence Chidzambwa and Jasmine Tehrani

Informatics Research Centre, The University of Reading, Reading, RG6 6AH, U.K.

Keywords: Organisational Semiotics, Business Process Modelling, Norm Analysis, DEMO, e-Government.

Abstract: A successful system first begins with an understanding of the business processes of an organisation. As

such, business process modelling (BPM) represents a collection of related, structured activities or set of

tasks that produce a specific service or product to stakeholders. It graphically represents how a business

organisation conducts their business processes conceptually. Throughout the literature, some challenges

with BPM have emerged, such as standardisation of process modelling, identification of the value of process

modelling, and model-driven process execution. However, one of the most challenging issues in business

process management is that organisations are traditionally considered to be static networks of transaction

processes rather than dynamic. There is therefore a need to aide analysts and practitioners alike by providing

methods that can guide and capture the dynamic aspects of an organisation. This paper aims to present two

BPM methods, and discusses extending them using the norm analysis method (NAM) to enable the analysts

to model the dynamics of business processes and to accommodate exceptions that have not been dealt with

by other conventional methods.

1 INTRODUCTION

Adding value to business process has become

nowadays more and more the objective of organising

business, in contrast to the traditional hierarchy

perspective. As such, the concept of business

process modelling (BPM) is a very popular way in

which to better understand business processes.

Throughout the literature, most experts in the field,

in particular, information technology and business

engineers, have suggested that a successful system

first begins with an understanding of the business

processes of an organisation (Davies et al., 2006).

As such, business process has emerged as an

important and relevant domain to facilitate the

development of software, analysis of requirements,

and re-engineering (Davies et al., 2006); (Recker et

al., 2009). BPM represents a collection of related,

structured activities or set of tasks that produce a

specific service or product to stakeholders. BPM is

typically performed by business analysts and

managers who are seeking to improve process

efficiency and quality in organisations. Hence, BPM

is a way in which to graphically represent how

business organisations conduct their business

processes conceptually. There are many BPM

conceptual models, for example, in a recent study by

Davies et al. (2006), they conclude that the most

common modelling techniques and methods used by

practitioners in business organisations are ER

diagramming, data flow diagramming, systems

flowcharting, workflow modelling, RAD, and UML;

all of which provide the means to represent the real

world conceptually. As such, BPM is considered to

be a key tool for the analysis and design of

information system in business organisations.

Notably, there are some challenges with BPM. Such

as, standardisation of process modelling,

identification of the value of process modelling, and

model-driven process execution (Indulska et al.,

2009). However, one of the most challenging issues

in business process management is that

organisations are traditionally considered to be static

networks of transaction processes rather than

dynamic. Van der Aalst et al. (2003) confirms such

fact in the context of software development and state

that “the goal is clear and it is easy to see that

software development [within organisations] has

become more dynamic”. Organisations are dynamic

networks of interrelated transaction processes. When

examining the inter-workings of organisations, the

dynamic aspects need to be considered (Liu et al.,

196

Liu K., Al-rajhi M., R. Alsoud A., Chidzambwa L. and Tehrani J..

Modeling Dynamic Behavior of Business Organisations - Extension of BPM with Norms.

DOI: 10.5220/0004142101960201

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2012), pages 196-201

ISBN: 978-989-8565-31-0

Copyright

c

2012 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2003). The popularity of business process

orientation has produced a fast growing number of

methodologies, modelling techniques, and tools to

support it (Charfi et al., 2010). The process of

selecting the right technique and the right tool has

become more and more complex not only because of

the huge range of approaches available, but also due

to the complex dynamic nature of large

organisations. There is therefore a need to aide

analyst and practitioners alike by providing methods

that can guide and capture the dynamic aspects of an

organisation. This paper builds on previous work on

modelling the dynamic behaviour of business

organisations (Liu, 2000) by presenting two BPM

methods, and discusses extending them using norm

analysis method (NAM) to enable the analysts to

model the business processes and to accommodate

exceptions which have not been dealt with by other

conventional methods (Liu, 2001); (Stamper, 2001).

Norm analysis is method used to model the dynamic

conditions of patterns of behaviour. Patterns of

behaviour, in turn, share a set of ‘norms’ which

govern how members behave, think, and make

judgment. There are many types of norms depending

on the way in which norms control human

behaviour; however, for the purpose of this paper the

analysis will focus on behavioural norms, which

govern people’s behaviour within regular patterns

(Liu and Dix, 1997).

The aim of this paper is two-fold. On the one

hand, it is to aid in modelling the dynamic behaviour

of business organisations. On the other hand, it is to

demonstrate the applicability of ‘norms’ with two

BPM methods through presenting two case studies

as a research method. The following section

introduces two examples of modelling organisational

processes, the notion of norms, and two case studies

one in e-Government services and the other in home

telecare. The paper ends with a discussion and

conclusion.

2.1 Examples of Modelling

Organisational Processes

2.1.1 Life-event Approach

The extraordinary growth in government

information and services published and provided

online raises a need for an efficient way to structure

these government contents and to effectively deliver

them to citizens. Life-event approach satisfies this

need by being citizen-centric through providing

these services based on real life-events and

situations in order to facilitate and enhance citizens’

experience when accessing governmental

information and services. In information systems

literature, Wimmer and Tambouris (2002) define

life-events as a way to describe situations of human

beings where public services may be required, or

triggered according to Kavadias and Tambouris

(2003) definition. According to Momotko et al

(2006) most of the existing technologies that are

used to implement life-events are either too static or

too dynamic. Static as they cannot offer an effective

way to incorporate potential differences in the needs

and circumstances of a citizen or they are too

dynamic to be used effectively by public

administrations (Momotko et al., 2006). Therefore,

they proposed an approach for implementing life-

events based on generic workflows technologies by

using workflow management. This organises life-

events as processes and rule management to make

them more flexible by including dynamic rules.

They define the term “dynamic” as rules that can be

validated at execution phase and during simulation.

However, their use of dynamic rules is limited to

identifying the responsible agent for the execution

process.

2.1.2 DEMO

Dynamic essential modelling of organisations

(DEMO) (Dietz, 1999) is a communication based

modelling methodology aligned to language action

perspective (LAP) theory. DEMO uses high-level

process descriptions to analyse processes at the

ontological level instead of focusing on

implementation details. It highlights communication

patterns between human actors, instead of the

sequences in which activities are performed. The

aim is to highlight the commitments that are entered

during the communication process as drivers of

action that is subsequently performed (Dietz, 1999).

One of five DEMO models is the business

process model (BPM). Causal and conditional

relationships are highlighted in BPM. The causal

relationship cause the start of a transaction and a

conditional relationship forms a condition of the

start or completion of another. Although DEMO

BPM shows such conditions, the process model is

only capable of capturing static conditions and does

not show dynamic conditions the exclusive-or

transaction. Unexpected events might occur that

require human judgement. These exceptions are

difficult to represent using a process diagram.

Catering for exceptional situations in behaviour is

handled well by norm analysis.

ModelingDynamicBehaviorofBusinessOrganisations-ExtensionofBPMwithNorms

197

3 NORM – A KEY CONCEPT

Norms exist in a community and will govern how

members behave, think, make judgements and

perceive the world. Norms are represented in various

kinds of signs, whether in documents, oral

communication or software code. A norm is more

like a field of force that makes members of the

society tend to behave in a certain way. As (Wright,

1963) explains: Norm has several partial synonyms

which are good English. ‘Patterns’, ‘standard’ and

‘type’ are such words. So are ‘regulation’, ‘rule’ and

‘law’ ”. The shared norms are what defined a culture

or subculture. In an organisation, norms reflect

regularities in the behaviour of members allowing

co-ordination of their actions. Norms are developed

through practical experiences of agents in a society

and in turn have functions of directing, coordinating

and controlling actions within society (Liu, 2000).

Therefore, an organisation is system of social agents

where people conduct themselves in an organised

way by conforming to regularities of perception,

behaviour, belief and value. The function of norm is

to determine whether patterns of behaviour are

lawful or acceptable in the context of the society.

3.1 Specification of Norms

Once the organisational norms are identified, it is

possible to express rules using general shape:

If <condition> then <consequent>

However, norms do not constitute a closed logical

system and in an actual situation, there are variations

to be considered as people do not always conform to

every organisational norms. When modelling the

agent and the actions, which reveals the repertoire of

available behaviour of the agent, the norms will

supply the rationale for actions. Therefore, to

capture and formally represent norms additional

components including the authority(s) of action

(agent), the effect and content of the norm, norm

subject and context have to be considered (Wright,

1963). Behavioural norms prescribe what people

must, may or must not do. These are equivalent to

their fundamental deontic operators, ‘obliged’,

‘permitted’ and ‘prohibited’. The following format is

considered suitable for specification of behavioural

norms (Liu and Dix, 1997).

Whenever <condition> If <state> Then <agent> Is

<deontic operator> To <action>

The condition clause, describes the matching

mechanism to apply. It clarifies the context in which

norm can be applied and defines the data the norm

subject requires. The actor clause describes authority

(s) of action that is responsible for the action. The

action clause specifies the consequence of norm,

which can be an action, or generation of

information.

Norm analysis gives a means to formally specify

the general patterns of behaviour in business

systems. The analysis of patterns of behaviour

focuses on the social, cultural and organisational

norms that govern the actions of agents in business

domain. In general, a complete NA is performed in

four steps, which are described in table 1.

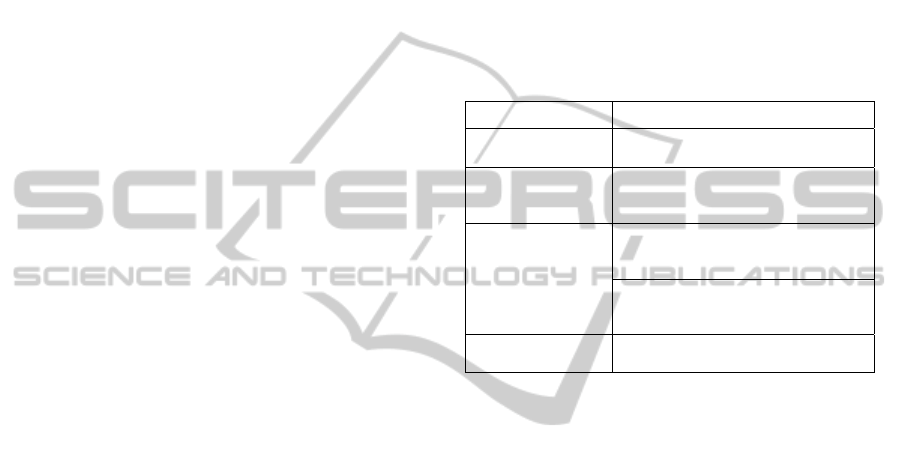

Table 1: Main stages on norm analysis.

Norm ID Description

Responsibility

analysis

Identify responsible agents,

i.e. norm subject

Proto-norm analysis

Select types of information required

by the

execution of the norm

Trigger analysis

Pre-condition:

The conditions before invoking the

norm

Post-condition:

The resultant after the successful

execution of the norm

Detailed norm

specification

Norms specified in the standard

format

4 LIFE-EVENT ORIENTED

E-GOVERNMENT SERVICES

Life-Event Approach is an emergent paradigm for

providing e-government services and information to

citizens, by distributing information and available

electronic services (e-services) according to the

major events of a citizen's life such as birth,

education, employment and marriage. It can be a

citizen lifecycle from birth to death. Life-events

describe situations where citizens may require one or

more of e-government services. The adoption of life-

event approach enables the service selection process

to be more tailored to citizen needs at a particular

time of their life (Dias and Rafael, 2007).What

makes it attractive is that a sequence of relevant

services can result from a single request. For

instance, in “getting married” life-event; the citizen

with a single request and, ideally, a single form,

could update all relevant departments on the new

marital status, request for new personal documents,

or obtain any other relevant information.

However, this cannot be achieved in a systematic

way unless life-events are matched to relevant e-

services in a dynamic manner. Therefore, a matching

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

198

mechanism is needed to provide public e-services

based on some needs that have been implied due to

the occurrence of a particular life-event. Using

norms is a promising solution for such a challenge,

especially after the failure of current technologies in

supporting the “publish and find” process of the core

e-service provision (Atkinson et al., 2007). Norms

can play a key role in supporting the standard

service brokerage model by identifying actual

service needs (implications of life-events) to be used

in finding the related services in the service registry.

Life-events are matched with relevant services using

the two ends of the norm construct. The workflow of

the activities in life-event oriented e-government

service provision system can be controlled using

norms, which can trigger the relevant e-services of a

particular life-event that are by a citizen.

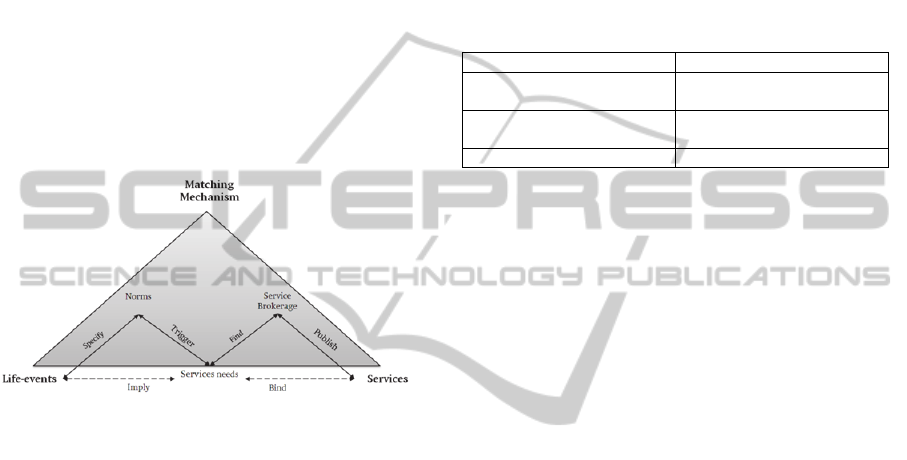

Figure 1: Matching Life-events with e-services using

norms.

Norms can capture conditions and assign them to

the responsible agents who can be a citizen (either

the bride/wife or the groom/husband or both in some

instances), a registrar (in this case registrar is a

government officer at registrar office), or a system

(government portal), and identify the actions that are

associated with them. Norms can be checked against

citizen profiles to determine the eligibility for a

particular service. Norms can be useful to govern the

static workflow of processes in life-event oriented e-

government service provision system.

5 EXTENDING DEMO WITH

NORMS (HOME TELECARE

CASE STUDY)

Home telecare is the application of electronic and

communication technology in caring for individuals

at home. Before the service is installed it is essential

to define the condition of the service user in order to

determine their care needs. The best way to manage

the expectations of users whilst raising acceptance

and commitment to solutions is to let them define

their important needs and express how they wish

those needs to be met. Discussion between the user

and assessor clarifies the acceptable statements and

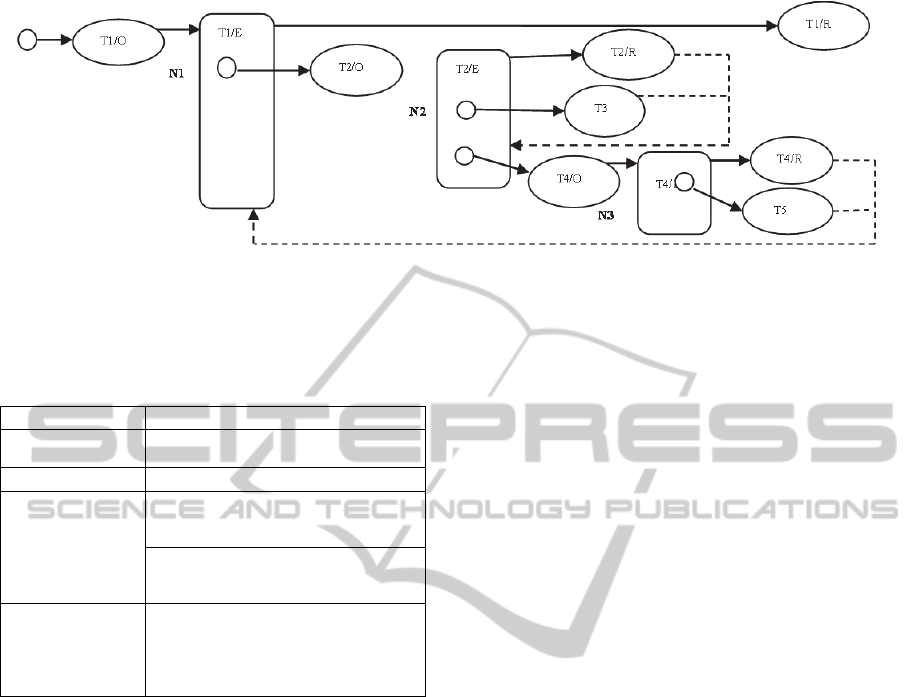

aligns them to service goals. Table 2 shows the

transactions that take place during the assessment

procedure as represented by DEMO. The transaction

type is represented by “T” e.g. T1 and represented

by a disk in Figure 2.

Table 2: Transaction results on compiling service user

preferences using DEMO.

Transaction type Transaction result

T1 Compile user care

preferences

F1 Preferences defined

T2 Request condition

definition

F2 User condition defined

T3 Define care problems F3 Care problems defined

Home telecare is applied to the elderly, disabled

and those with learning living in their homes. Family

members and carers are usually involved in user

assessment. Perceptual norms are applied in defining

user conditions and cognitive norms are applied in

defining causal relationships between care problem

and condition. Axiological norms are applied in

selecting care preferences. These norms affect how

the individual behaves. Behavioural norms give

structure to the complex world between actors.

These norms are added to business process diagrams

in order to guide the prediction and collaboration of

future behaviour as design norms.

Conditions prevail which are not covered by

static process diagrams but can be captured by

applying norms. For example from Table 2 the

service user, their representative or both can define

user condition with the assessor. The user might

only give one intervention preference which means

there is no ranking required. The individual values,

which would have been identified by ranking

interventions, are still be required to understand the

values impacting user decision making.. If valuation

of interventions is dependent on external forces then

those forces need to be involved in decision making

because decisions done in their absence will not hold

and may need to be revisited. Whilst DEMO

identifies the core transaction it does not capture the

dynamic properties of the transaction. This is

important where social factors play an important role

in the commitment that is made by the stakeholders

like in home telecare. For example to capture the

value system of a service user the norm in Table 3 is

identified. Capturing these dynamic aspects provides

greater flexibility in the execution of the tasks whilst

ensuring that the objective of the transaction is

ModelingDynamicBehaviorofBusinessOrganisations-ExtensionofBPMwithNorms

199

Figure 2: Business process diagram for compiling user preferences using DEMO BPM.

achieved. Using norms enables the inclusion of

social aspects in systems design.

Table 3: Result of norm analysis.

Norm ID: N3 Determining service user value system

Responsibility

analysis

Assessor

Proto-norm analysis Identified care need/s

Trigger analysis

Pre-condition:

The user has not provided information on

their value system

Post condition:

How user values acceptable care has been

established

Detailed norm

specification

Whenever there is one care intervention

preference given if the service user has

provided information on their value

system, then the assessor is prohibited to

ask other value related questions

6 DISCUSSION AND

CONCLUSIONS

As mentioned previously, the aim of this paper is

two-fold, 1) To aid in modelling the dynamic

behaviour of business organisations, and 2) To

demonstrate the applicability of ‘norms’ using two

BPM methods. In this sense, extending the BPM

method using ‘norms’ enables analysts to model the

dynamic behaviour of organisations, which has not

been dealt with by other conventional methods. The

paper contributes to the notion that organisations are

not static networks of transaction processes but

rather dynamic ones, by aiding analysts with

modelling the dynamic networks of interrelated

transaction processes. We have demonstrated the

applicability of ‘norms’ using two BPM methods:

The life-event oriented e-government and the home

telecare system. As supported by both case studies,

the applicability of extending the method using the

norm analysis method is demonstrated. It is also

shown, given that it has been feasible to study and

define the patterns of behaviour within each case

study, that norms play a vital role in identifying the

responsibility and eligibility of both e-government

and telecare services, as well as in defining the

consequences. When examining the inter-workings

of organisations, bearing in mind that organisations

are dynamic networks of interrelated transaction

processes, the dynamic aspects of such inter-

workings need to be considered (Liu et al., 2003).

Hence, information systems consist of social as well

as technical dimensions all of which need to be

taken into consideration. With the realisation that the

individual is not outside, but is indeed part of the

system, the importance of addressing users’ social

requirements, from a system design perspective, is

increased. Thus, in telecare provision we need to

understand which personal norms may impact the

acceptance or use of the telecare solution. Bearing

this in mind, we conclude that it is not only the

technical functions of the devices that matter for the

successful deployment of telecare systems. Instead,

the social aspects also play an important part in such

process and therefore warrant consideration in

designing systems. The structuring of these social

aspects using norm analysis enables their inclusion

in technical systems and therefore can be automated.

A current limitation may be the management of the

increasingly complex set of norms underlying large

organisations. An avenue for future work is to

develop a way in which to manage such large sets of

norms. Overall, extending BPM by norms helps to

ensure that both, the social and technical systems,

are captured and documented. The strength of this

modelling approach results from the powerful base

methods: DEMO and NAM. DEMO, on the one

hand, is a rigorous approach that provides a solid

understanding, first, of the types of transactions that

take place within an organisation; second, of the

participants involved in these transactions; third, the

information that is needed and created while

KMIS2012-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

200

carrying through the transactions; and fourth, the

relationship between the different transaction types.

NAM, on the other hand, enables the analyst to

specify business rules, which is necessary for

systems design. The specification of norms allows

the recognition of human responsibilities and

obligations. In addition, it has been demonstrated

that NAM allows the modelling of the dynamics of

business organisations, since deontic operators

facilitate modelling situations were decisions are

made solely based on human judgment and there is a

degree of flexibility in patterns of behaviour. The

extended method of DEMO with NAM leads to a

powerful modelling approach for information

systems analysis and design in business

organisations.

REFERENCES

Atkinson, C., Bostan, p., Hummel, O. & Stoll, D.: A

practical approach to web service discovery and

retrieval. In 2007. IEEE, 241-248.

Charfi, A., Müller, H. & Mezini, M., 2010. Aspect-

Oriented Business Process Modeling with AO4BPMN

Modelling Foundations and Applications. In: Kühne,

T., Selic, B., Gervais, M.-P. & Terrier, F. (eds.).

Springer Berlin / Heidelberg.

Davies, I., Green, P., Rosemann, M., Indulska, M. &

Gallo, S., 2006. How do practitioners use conceptual

modeling in practice? Data & Knowledge

Engineering, 58, 358-380.

Dias, G. P. & Rafael, J. A., 2007. A simple model and a

distributed architecture for realizing one-stop e-

government. Electronic commerce research and

applications, 6, 81-90.

Dietz, J. L. G., 1999. Understanding and Modelling

Business Processes with DEMO. In:

SPRINGERLINK (ed.) Lecture Notes in Computer

Science 1999.

Filipe, J. & Liu, K.: The EDA model: an organizational

semiotics perspective to norm-based agent design. In,

2000. Citeseer.

Indulska, M., Recker, J., Rosemann, M. & Green, P.:

Business process modeling: Current issues and future

challenges. In, 2009. Springer, 501-514.

LIU, K., 2000. Semiotics in information systems

engineering, Cambridge ; New York, Cambridge

University Press.

Liu, K., Sun, L., Barjis, J. & Dietz, J. L. G., 2003.

Modelling dynamic behaviour of business

organisations—extension of DEMO from a semiotic

perspective. Knowledge-Based Systems, 16, 101-111.

Momotko, M., Tambouris, E., Bliźniuk, G., Izdebski, W.

& Tarabanis, K.: Towards implementation of life

events using generic workflows. In 2006.

Recker, J. C., Rosemann, M., Indulska, M. & Green, P.,

2009. Business process modeling: a comparative

analysis. Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, 10, 333-363.

Stamper, R. K., 2001. Organisational semiotics:

Informatics without the computer. Information,

organisation and technology: Studies in

organisational semiotics, 115-171.

Tan, S., 2006. A Semiotic Approach to Enterprise

Infrastructure Modelling—The Problem Articulation

Method for Analysis and Applications. Phd, University

of Reading.

van der Aalst, W., Ter Hofstede, A. & Weske, M., 2003.

Business process management: A survey. Business

Process Management, 1019-1019.

Wright, G. H., 1963. Norm and action: a logical enquiry,

Humanities Press.

ModelingDynamicBehaviorofBusinessOrganisations-ExtensionofBPMwithNorms

201