Modeling the Design of Value in Service-oriented Business Models

Arash Golnam

1

, Paavo Ritala

2

, Vijay Viswanathan

1

, Valerian Hanser

1

and Alain Wegmann

1

1

Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, School of Computer and Communication, Sciences (I&C),

Systemic Modeling Laboratory (LAMS), Station 14, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland

2

Lappeenranta University of Technology, School of Business

PO Box 20, FI-53851 Lappeenranta, Finland

{arash.golnam, vijay.viswanathan, valerian.hanser, alain.wegmann}@epfl.ch, ritala@lut.fi

Keywords: Amazon.com, Modeling, Service-Oriented Business Models, Value Capture, Value Creation.

Abstract: Many firms redesign their business models to be service-oriented in light of the increasingly central role that

services play in their business models. Two fundamental questions should be addressed in designing

service-oriented business models: how is value created for and with the customers by the service provider?

and, how is the value captured by the service provider?. The first question deals with “value creation” while

the second addresses “value capture” in the “service value equation”. A service-oriented business model that

addresses these two questions can sustain the viability and competitiveness of the firm as a service provider.

The extant research mainly focuses on the service design from the value creation perspective. Thereby, there

has been little discussion about service providers’ value capture and its trade off with value created for and

with service customers. In this paper, adapting a holistic perspective, we introduce a modeling framework

that can assist in understanding, analysis and design of value (i.e. value creation and capture and their

interplay) in service-oriented business models. Our modeling framework is grounded in insights and

conceptualizations of the extant theories, constructs and frameworks on value creation and capture in

business and service systems. We illustrate the applicability of our framework by conducting a descriptive

case study of the value creation and capture in Amazon service system in the period between 1997 and

2001.

1 INTRODUCTION

A business model is defined as a generic platform

between strategy and practice, describing the design

or architecture of the value creation, delivery, and

capture mechanisms the firm employs (e.g. Teece,

2010). Due to the increasing and even focal role of

services in their businesses and strategy, many firms

have been forced to completely re-think their

business models (Teece, 2010). In fact, this recent

tendency of business model redesign has led to the

emergence of “service-oriented business models”.

This development can be explained from the

perspective of “service-dominant (S-D) logic”

(Vargo and Lusch, 2004 and 2008), that attempts to

view and extend the concept of service beyond a

“particular” kind of intangible good as traditionally

viewed in the “goods-dominant (G-D) logic”. S-D

perspective conceptualizes a firm’s offerings not as

an output, but as an input for the customer's value-

creation process.

Central to the service-oriented business models

are the concepts of value creation and capture. In

order to understand how a service-oriented business

model remains viable and competitive, two

fundamental questions should be addressed: “how is

value created for and with the customers by the

service provider?” and, “how is the value captured

by the service provider” (for discussion, see e.g.

Grönroos and Ravald, 2011; Bowman and

Ambrosini, 2011; Pitelis, 2009; Ritala et al., 2011).

In the search for understanding such questions, the

extant research has developed value modeling

frameworks such as (Gordijn and Akkermans, 2003;

Weigand et al. 2009; Pijpers and Gordijn, 2007; Yu,

1997; Weigand, 2009; Osterwalder and Pigneur,

2010) that provide conceptual tools to support the

design of service offerings. However, such tools and

framework mainly address the service design from

the service customers’ perspective and do not

sufficiently address suppliers’ value capture in the

“service value equation”. The same gap can be

broadly identified in the service literature in general,

81

Golnam A., Ritala P., Viswanathan V., Hanser V. and Wegmann A.

Modeling the Design of Value in Service-oriented Business Models.

DOI: 10.5220/0004461400810093

In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design (BMSD 2012), pages 81-93

ISBN: 978-989-8565-26-6

Copyright

c

2012 by SCITEPRESS – Science and Technology Publications, Lda. All rights reserved

where value creation and co-creation issues have

been emphasized over value capture. In addition, the

interplay between value creation for and with

customers and value capture by the suppliers has not

been explicitly investigated in the design and

analysis of service offering in service-oriented

business models.

In this study, we propose a holistic approach that

takes into account both value creation (for and with

customers) and value capture (by service providers)

in order to fully understand and model the new logic

of service provisioning process in service-oriented

business models. To this end, our research aims to

provide a modeling framework that can assist in

understanding, analysis and design of value (i.e.

value creation and capture and their interplay) in

service-oriented business models. We illustrate the

applicability of our framework by means of a

descriptive case study of the value creation and

capture in Amazon.com service system. In a

descriptive case study, the researcher pursues to

describe a phenomenon of interest that occurs within

the data. This type of research begins with an a

priori theoretical perspective. Then, a pattern

matching is conducted to describe the phenomenon

in the data in a rigorous way (Yin, 2009). More

specifically, the descriptive case we conduct can be

labelled as an instrumental case study (Stake, 1995),

where we aim to illustrate the applicability of the

suggested framework. The case study focuses on one

of the services offered by Amazon.com, more

particularly; the sales of used and new books in

Amazon.com over the period 1997-2001.

We have used data triangulation in order to

gather rich evidence on Amazon.com, various

aspects of its business model and its service

offerings over time. We began the data gathering

process in January 2009. Since then, a variety of

secondary data sources have been accessed,

analyzed and synthesized in order to gain an

accurate understanding of diverse facets of

Amazon.com’s service offerings and implementation

in Amazon Marketplace. Such sources include:

• Amazon.com annual reports between 1997–

2010 (Amazon, 2011a); presentations and

news releases (Amazon, 2011b).

• Books published on Amazon.com such as;

Afuah and Tucci, 2002; Spector, 2002;

Kalpanik and Zheng, 2011), etc.

• Harvard Business Review (HBR) cases

published between 2000 and 2010 such as

(Applegate 2002 and 2008)

• Journal articles such as (Heck and Vervest,

2007), etc.

There are several advantages in using secondary

sources. For instance, in Ambrosini et al. (2010)

suggest that teaching cases are an unexploited and

rich source of data that should be used when primary

data is not available. They also suggested using

reputable sources for teaching cases (we mainly use

Harvard Business Review cases here) and combine it

with other sources to attain data triangulation.

Analyzing multiple sources of objective and

subjective evidence has enabled us to combine

evidence in a way that gives an overall

understanding of the research topic.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2

we present a conceptual model that summarizes the

theoretical insights and perspectives on value

creation and capture. In Section 3, after a brief

introduction to Amazon.com we represent the design

of value Amazon.com’s business model applying

our value modeling framework. Section 4 includes

the related work and in section 5, we present the

conclusion and the future work.

2 THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL

In this section, we develop a theoretical framework

examining value creation and capture in service

systems. The theoretical insights are presented in

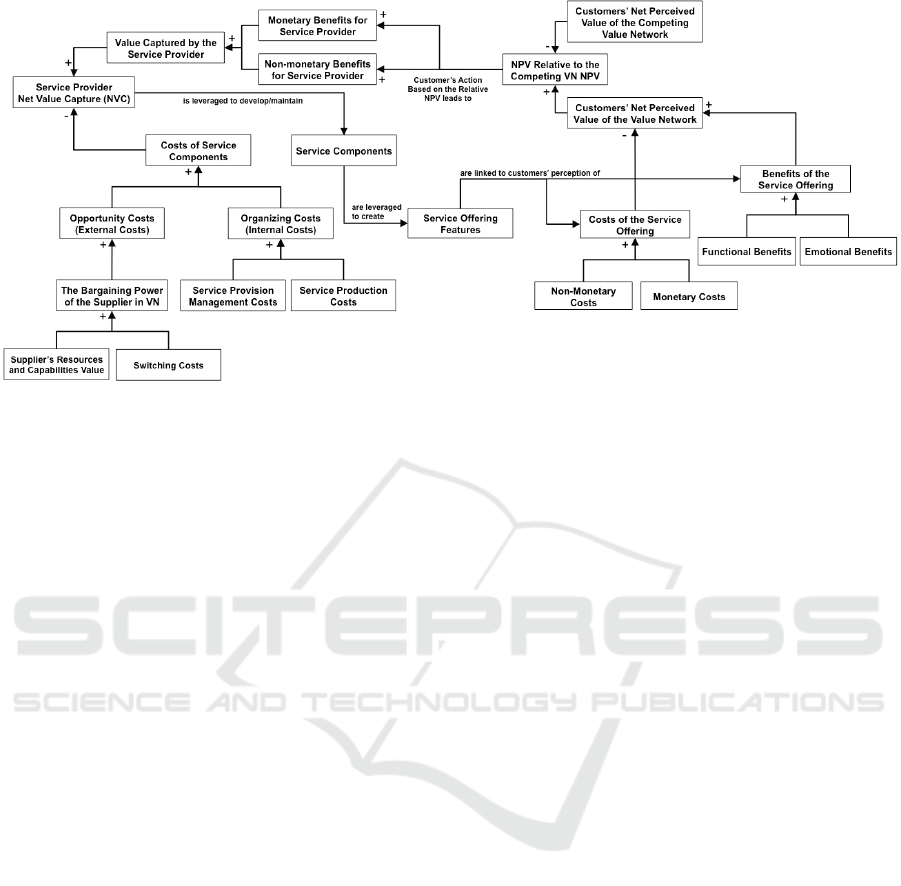

form of a conceptual model illustrated in Figure 1.

In the following, we first discuss the tenets of

customer value creation and then we proceed to

examine how the service provider eventually

captures value.

2.1 Customer Value Creation

Conceptualizations

Creating value for the customers is the fundamental

reason why any company exists and thrives in

competition (e.g. Bowman and Ambrosini, 2000),

and customer value creation is most pronounced in

service-oriented companies (Chesbrough and

Spohrer, 2006). Customer value creation is a

process, where the service provider delivers the

customer a service offering that creates value when

the customer uses the service, i.e. the use value (see

e.g. Grönroos and Ravald, 2011). In this setting, the

service provider (and its value network) is

responsible in producing the service, and actual

customer value (co-)creation takes place when

customer receives/uses the service (ibid.). The main

interface where the service provider can affect

customer value creation (e.g. time saving

convenience) is through a concrete service offering

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

82

Figure 1: The conceptual model.

(e.g. transportation, entertainment). In order to

provide any type service offering, the provider has a

set of service components that are leveraged to

create the service offering (Golnam et al., 2012).

These components are created by the service

provider and its value network, and they reflect the

underlying resources and capabilities that are put to

use to provide a certain set of service components.

Thus, service components can be seen as a way of

organizing the service, while service offering

features are those that are linked to the actual

customer’s perceptions of service value.

2.1.1 Net Perceived Value (NPV)

In understanding customer value creation from the

customer perspective, the net perceived value has

been seen as a key concept, which is related to the

overall benefits minus the costs of receiving the

service (e.g. Kotler, 2000; Day, 1990; Huber, 2001).

A related concept is the consumer surplus, in

layman’s terms often expressed as “value for

money”, that Bowman and Ambrosini (2000) define

more precisely as the difference between the

monetary amount the consumer is willing to pay and

the actual price paid. It is important to recognize that

consumer surplus or net perceived value is assessed

ex-ante, i.e. prior to the transaction. This is precisely

the reason why benefits and costs are assessed as

“perceived”; this is in contrast to complementary

concepts such as consumer satisfaction, which are

ex-post. For instance, if a service offering consists of

entertainment services, the customer perceives a

certain value for being entertained, while costs of

receiving

it are linked to e.g. to time spent to going

to the venue, as well as the monetary costs involved.

Thus, in any situation where a transaction

actually occurs it is expected that net perceived

value will be positive. That is, the customer is

willing to pay an amount in excess of the costs

(including monetary and non-monetary costs), and

thus made the purchase, pocketing the “surplus”.

The larger this surplus is the more eager the

consumer will be to make the purchase; the converse

is also true, the smaller this surplus becomes, the

less eager the consumer is in willing to engage in the

transaction. The borderline situation is that of the

monopoly supplier, where the firm is able to charge

exactly the maximum amount the consumer is

willing to pay, thus netting zero surplus for the

consumer. Therefore net perceived value can only

increase through one of the following situations: (1)

an increase in perceived benefits while maintaining

perceived costs unchanged; (2) a decrease in

perceived costs while maintaining perceived benefits

unchanged; or (3) a simultaneous increase in

perceived benefits with a decrease in perceived

costs.

2.1.2 Customers’ Perception of Service

Offering’s Benefits

Customer’s perceptions of the benefits are related to

the use value of the service for the customer (e.g.

Grönroos and Ravald, 2011). Use value covers the

specific characteristics of the product or service

perceived by the customer as potentially serving

their needs. Bowman and Ambrosini (2000)

emphasize the subjective nature of use value - it

maps uniquely to each customer. Use value itself can

Modeling the Design of Value in Service-oriented Business Models

83

be further categorized into two sub-components,

namely functional and emotional benefits.

Functional benefits represent the tangible

benefits of the product or service that fulfill the

primary needs the consumer had in seeking the

solution, and Grönroos (2000) calls this the “core

value” of the service. Kotler’s (2000) pinpoints that

these benefits – although functional – are expressed

in customer terms, further reinforcing their

subjective nature. Furthermore, as discussed by

Amabile (1996), customers make their subjective

assessment of appropriateness of the functional

benefit of the service. In the majority of cases, where

the product and context are well understood and

established, the process is straightforward. However,

in cases of innovation and disruptive products, or

change in social and cultural context, buyers might

not be able to properly make their assessment,

resulting in a net negative impact on functional

benefits.

Emotional benefits are made up of the intangible

extras that the firm is able to offer that go above and

beyond meeting primary needs; the analogous

terminology of Grönroos (2000) is added value.

Kotler (2000) highlights various specific strands of

these types of benefits, such as personal interaction

value and image value. Groth (1994) also suggests

that customers buy products and services for other

than just “pure [i.e. functional] utilitarian reasons”.

He provides the example of consumers not assigning

significant value to near-perfect replications of

famous art work as a case-in-point. Groth terms this

kind of utility, serving the psychic needs of people,

as an exclusive value premium (EVP).

2.1.3 Customers’ Perceptions of Service

Offering’s Costs

In addition to various types of benefits, there are

always costs incurring to the customers of receiving

a service. The extant literature details the many

types of such costs. The most obvious is the actual

monetary cost (i.e. exchange value, Bowman and

Ambrosini., 2000) In addition, it is also important to

take into account the non-monetary costs. Regarding

these, Kotler (2000) identifies three other varieties:

time, energy, and psychic costs. Time cost is made

up by the sum of durations the consumer has to

spend in acquiring and acquainting oneself with the

product or service. Energy cost is the net of energy

that needs to be expended by the customer. Finally

psychic costs form a complement to psychic utility -

the cognitive stress experienced by the customer in

purchasing and using the product.

2.1.4 Competing Value Networks and the

Relative Net Perceived Value

In addition to the value created by the focal firm and

its value network, the net perceived value created by

competing value networks’ offerings should also be

taken into account. In analyzing this, we refer to

relative net perceived value, which is the net

perceived value created by the focal firm’s offering

in relation to the competing offerings. The higher the

relative net perceived value is, the higher is the

competitiveness of the focal firm in the eyes of the

customers.

2.2 Service Provider Value Capture

Conceptualizations

Value capture (also termed as value appropriation or

retention in some sources) by the focal firm is an

issue of much interest in management research and

even more so in organizations themselves. Value

capture is related to the actualized profit-making of a

certain party. Regarding this, an in-depth discussion

is provided by Bowman and Ambrosini. (2000)

where they address the importance of analytical

distinction between value creation and capture.

Lepak et al. (2007) also makes a point of mentioning

that “the process of value creation is often confused

or confounded with the process of value capture or

value retention” and that the two should be

understood as distinct processes.

While there is certainly a strong correlation

between the two, it is essential to recognize the

former neither automatically nor fully translates into

the latter. Bowman and Ambrosini (2000) argue that

while value is created for the customer by

organizational members (i.e. the value network),

value capture has a different set of determinants,

including “perceived power relationships between

economic actors” (in other words, the bargaining

power between the firm and other entities, which is

explored at depth below). Lepak et al. (2007) and

Ritala and Hurmelinna-Laukkanen (2009) follow a

similar line of argumentation, suggesting that only

through the use of specific mechanisms is the creator

of value able to capture it, and that value creation

and capture may have sometimes have completely

different determinants and timeframes.

2.2.1 Net Captured Value (NCV)

In our model, value capture by the service provided

is determined by the benefits/compensation it can

extract from the markets. Furthermore, the net

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

84

captured value (NCV) of the service provider

consists of two factors: the benefits for the service

provider minus the costs of service components. It is

notable that this view is symmetrical to the customer

side where the net perceived value of the customer is

also dependent on benefits and costs. However, the

perspective is different in that the service provider is

the producer of the value (which incurs costs), and is

receiving various types of compensation for doing

that.

In our model, the benefit side of net value

capture is fundamentally affected by customer’s

action, which are based on the net value of the

service as perceived by the customer. Customer’s

action means the activities that result in generating

more or less tangible (e.g. annual subscription fee)

and intangible (e.g. referrals, word-of-mouth,

loyalty) contributions by the customer for the service

provider as a compensation for the net perceived

value of the service offering. From the service

provider’s perspective, these actions then lead to

actual monetary and non-monetary benefits, which

are discussed next, and are followed by the

discussion on the costs of providing the service.

2.2.2 Benefits for the Service Provider

Benefits from the service provider range from direct

monetary benefits (i.e. revenue streams) to non-

monetary benefits (e.g. customer loyalty, learning).

While monetary benefits for the service provider are

quite straightforward to interpret (e.g. bulk price,

subscription fees etc.), the non-monetary benefits are

more varied and ambiguous. This is partly because

non-monetary benefits consist of non-negotiable

value, which means that these types of compensation

cannot be clearly agreed on between the parties.

Ulaga (2003) proposes various types of non-

negotiable value coming from the customers, such as

commitment, trust, satisfaction, and loyalty. Of

course non-negotiable values in and of themselves

are not the ultimate end for profit-seeking firms.

Thus arises the discussion as to conversion

mechanisms for non-negotiable value into negotiable

forms. Allee (2008) offers significant insight in this

regard, offering two pathways that this conversion

can take: (a) direct conversion into monetary value,

and (b) an intermediate conversion into a negotiable

form that can be bartered. For instance, customer

loyalty involves major (non-monetary) benefits for

the service provider, which may also contribute to

the monetary benefits in both short and long term. In

fact, customer loyalty manifests itself in the form of

repeat purchases and is thus strongly linked with

superior profits: Reicheld (1994) found out that “a

small increase in customer retention leads to a major

increase in net present value profits.”

In addition, organizations learn by doing and

thus constantly evolve themselves (e.g. Nelson and

Winter, 1982). Thus, one type of non-monetary

benefit is also linked to the organizational learning

in the form of trial-and-error, customer feedback,

and therefore improved service offerings. This type

of value is highly non-negotiable, but it may

translate into improved service offerings and value

creation in the future.

In assessing the received benefits for the

provider, the offerings of competing value networks

should also be taken into account. Receiving both

monetary and non-monetary benefits are linked to

the customer’s net perceived value relative to the

competing offerings, since this determines the

compensation customers are willing to pay (here:

customer’s actions) and contribute to compensate a

particular service provider. Thus, issues concerning

competitive pressure and competitors’ offerings are

important determinants on the eventual value

capture. Regarding this, Lepak et al. (2007) explains

that a consequence of competition is increased

supply, which following fundamental economic

principles, results in decrease in exchange value (i.e.

price). We suggest competition also decreases the

possibility of achieving non-monetary benefits, since

the potential places of customer loyalty, learning and

other benefits may be decreased if competitors are

too attractive.

2.2.3 Costs of the Service Components

In addition to the monetary and non-monetary

benefits for the service provider, the costs of

providing the service components affects value

capture. We divide these costs into two broad

categories: the internal organizing costs, and the

external opportunity costs. Combined, these costs

decrease the value captured by the service provider.

First, the organizing costs refer to the internal

costs of the service provider related to producing the

service components. These costs are comprised of

the production costs, related to producing firm's

offerings, and the management costs, related to

administration, control, monitoring, and incentives

in organizing firm’s operations (e.g. Masten et al.,

1991; Blomqvist et al., 2002).

Second, in addition to the organizing costs, the

value network includes costs dependent on the

suppliers of various independent or jointly provided

service components. Following Brandenburger and

Modeling the Design of Value in Service-oriented Business Models

85

Stuart (1996), we refer to the costs of the service

components provided by the suppliers/partners in the

service provider value network as opportunity costs.

Opportunity cost is defined as the financial

compensation provided to the suppliers in exchange

to the service components they provide to the

offering, also taking into account the highest

alternative compensation that they could receive

from utilizing their resources in other context (ibid.).

Thus, the economic rationale of the suppliers’

involvement in the service system is tied to the

opportunity costs of the suppliers in providing

certain service components. Opportunity cost is a

widely-recognized economic concept that is a

measurement of the best alternative passed up on. In

this analytic context opportunity cost is the option a

supplier foregoes in choosing instead to deal with

the focal firm – and in effect this determines the

eventual cost burden that needs to be taken into

account when analyzing the costs related to

maintaining the external network of suppliers and

partners.

The key issue affecting the opportunity costs of

the suppliers is the relative bargaining power.

Indeed, Bowman and Ambrosini (2000) argue that a

firm’s ability to bargain with suppliers and buyers

from a position of strength positively influences the

value it is able to capture. Macdonald et al. (2004)

reinforce this line of argumentation, with a formal

model, stating that bargaining is what determines a

firm’s “precise” level of capture. Similarly

Brandenburger and Stuart (1996) state that it is

bargaining power between the “players” that

determines the division of value, and further that

bargaining power is what determines the price of

exchange between supplier and firm. Simply put, the

higher the bargaining power of a focal firm relative

to its suppliers and partners, the lower are the

eventual costs that it has to pay for suppliers to be

involved in the value network, and vice versa. There

are several issues that affect the relative bargaining

power of actors. At its most basic level bargaining

power is garnered by the relative value of resources

and capabilities of different actors, determined by

e.g. rarity, inimitability, and non-substitutability of

those (see e.g. Barney, 1991). The relative

bargaining power is also affected by the switching

costs of the supplier. Switching costs is a general

microeconomics concept identifying the redundant

investment (monetary and otherwise) that a supplier

needs to make when switching customers. Porter

(1980) highlights the proportional relationship

between high switching costs and high bargaining

power. This means that the higher are the switching

costs of suppliers, the higher is the relative

bargaining power of the focal firm.

2.3 Net Captured Value and Future

Value Creation

The cyclical feedback that net captured value offers

to future value creation activity remains a relatively

unexplored domain in the literature. However, we

suggest that this should be taken into account when

building a practically oriented model of value

creation and capture. As the most evident issue, the

actual monetary value and related resources (i.e. the

revenue streams coming to service provider) directly

help to maintain service providing activities in that

they provide funding for the on-going operations.

In addition, and more important in longer term,

is the development of value creation activities that

take place over time. Lepak et al. (2007) touches on

this point in his conclusion, suggesting that “a key

question is whether actors learn from past value

creation efforts in terms of the amount of value they

capture and use this knowledge for decisions

regarding future value creation activities.” In other

words organizational learning accumulated by value

capture over time can guide a firm to better structure

its value creation efforts.

Thus, we suggest that over time, there is a

feedback loop from value capture to developing and

maintaining service components. In terms of

development of service components, the feedback

loop is a result of organizational learning, leading to

improved capabilities and resources related to

service production. This can lead to either increasing

the customers’ value, or cost reduction on the

service provider’s side, or both. In general, these

improvements can be linked to Porter’s (1980)

generic strategies of cost leadership and the second

as differentiation.

3 MODELING THE DESIGN OF

VALUE IN AMAZON.COM

BUSINESS MODEL

In July 1995 Amazon.com began as an online

bookseller and by September 1995, the company

was selling $20,000 per week. After nearly three

years as an online bookseller, the company began

aggressively diversifying its offerings to include

other product categories beyond books, initially

adding music, videos, toys, and electronics (

Afuah

and Tucci, 2002)

. Such diversifications were followed

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

86

by the launch of several other stores such as home

improvement software and etc. In parallel with such

product diversifications, in October 1998,

Amazon.com expanded geographically by launching

its first international sites Amazon.co.uk and

Amazon.de through the acquisition of UK-based

online bookstore Bookpages and German-owned

Telebook (Applegate, 2002). The rationale behind

such diversifications was Amazon.com’s strategy of

“get big fast” to turn Amazon into the biggest mass

merchandiser or E-mall in the online world (Spector,

2002).

Following its evolution from an online bookseller

or to an e-tailer by diversifying its product offering

through new store openings, Amazon.com extended

its business model to become a third-party market

place by launching Amazon Marketplace in

November 2000. Marketplace idea was then

implemented in Amazon.com’s international

websites, UK and Germany in 2002, and France,

Canada and Japan in 2003.

In the case study analyzed in this paper, we focus

on the Amazon.com’s evolution from an online

bookseller to a third-party Marketplace in the online

bookselling segment. From a service perspective, we

model the value creation and capture in

Amazon.com’s transition from selling new books to

establishing a partnership with other booksellers to

sell used and new books. To this end, we develop a

value model representing the design of value

creation and capture in Amazon.com business model

circa 1997. In order to map our modeling framework

to the theoretical discussions in the previous section

and to gain a better understanding of the modeling

constructs and notations, we present the model in

three parts (i.e. customer value; customer value

creation; and provider value capture) and explain

each part step by step. Finally, we discuss the

rationale behind changes in the business model of

Amazon.com in 2001 in light of the theoretical

insights embodied in our modeling framework.

3.1 Modeling Customer Value in

Amazon.com’s Business Model

The first part of our modeling framework deals with

the service value attributes as perceived by

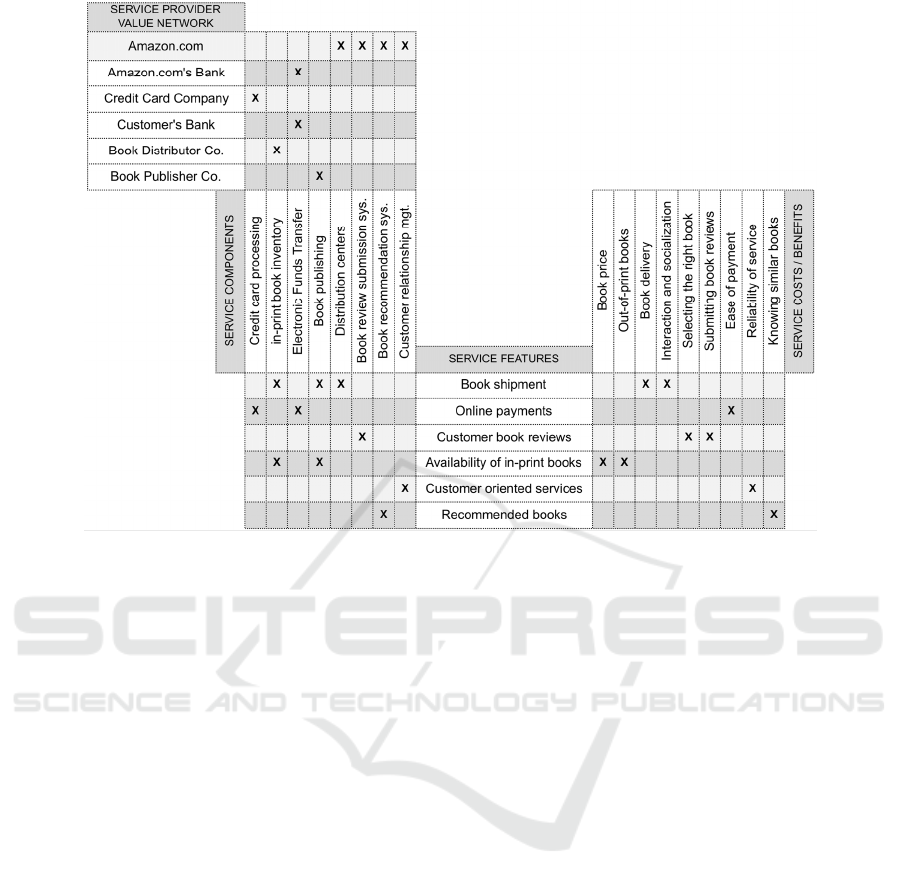

Amazon.com’s customers circa 1997. In Figure 2,

we have listed a number of value attributes to reflect

the perceptions of customers about the benefits and

costs of Amazon.com’s online book selling service.

In Section 2.1, we discussed that a customer assesses

a service based on its net perceived. The next step is

to understand the relative importance of value

Figure 2: Modeling customer value.

attributes in terms of their impact on the net

perceived value. As illustrated in Figure 2, we use

minuses and pluses to represent the nature of impact

(i.e. negative or positive) and its intensity (medium

or strong).

Information on customers’ perception and their

relative importance can be gathered through direct

interaction with customers or customer surveys.

Revealed preference methodologies (Carson et al.,

1996) can also be used to understand customer’s

needs and preferences based on their behavior. In

this paper, the information provided on the value

attributes the Amazon.com customers perceive and

their relative importance has been gathered through

the secondary sources outlined in Section 1.

As illustrated in Figure 2, different customers

can perceive different value attributes of the service

offered by the service provider. Similarly a value

attribute can have different impacts on different

customers. For instance as shown in Figure 2, the

value attributes “Ease of payment” and “Book

delivery” do not have any impact on Customer X’s

perception of Amazon.com’s service offering. By

the same token, “Submitting reviews” and

“Interaction and socialization” do not influence

Customer Y’s perception of service value.

Moreover, “Book price” and the “Reliability of

service” are more important for Customer Y.

Whereas, Customer X cares more about value

attributes such as (availability of) “Out-of-print

books” and “Knowing about similar books”.

Finally, as already discussed in Section 2, it is

important to identify the strategic positioning of the

Modeling the Design of Value in Service-oriented Business Models

87

Figure 3: Modeling customer value creation.

service provider by understanding where the

provider is standing relative to the competing value

networks in terms of the value attributes. This assists

the service provider in identifying the service

improvement opportunities as well as analyzing

whether delivering the perceived value attributes

results in a competitive advantage. In our example

we compare Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble and the

Bookstores with respect to the value attributes listed

in the model. By Bookstores we refer to small and

independent bookstores that were not a part of the

book superstores or chains such as Barnes and Noble

or Borders. As illustrated, Bookstores were doing

better in the price and availability of out-of-print

books. Bookstores superiority in these two value

dimensions was mainly due to selling used books.

3.2 Modeling Customer Value Creation

in Amazon.com’s Business Model

The previous section focused on the analysis of

value attributes and their impact on net perceived

value as well as the strategic positioning of the

service relative to the competition. In this section we

present the design of the value creation process.

Figure 3 illustrates the value creation process in

Amazon.com business model wherein we model the

service features created by the service components

that are provided by the service provider and its

value network and their corresponding value

attributes. In the model, we put an X to map the

service components to service features and service

features to the value attributes. More concretely, we

can see that for instance, Amazon.com provides the

service component “Book recommendation system”

which creates the service feature “Recommended

books” that is linked to the value attribute “knowing

similar books”. Similarly, the Distributor Co. holds

an “In-print book inventory” that creates the feature

“Availability of in-print books” which pertains to the

value attribute “Book delivery”.

3.3 Modeling Service Provider Value

Capture in Amazon.Com’s

Business Model

In Section 2 we explored different choices available

to service providers to increase their net captured

value (NCV). As discussed in section 2.2.2 the

monetary and non-monetary benefits created by the

customers determine the value captured by the

service provider that increases the net value captured

by the service supplier. The costs of the service

components (i.e. organizing cost of service provider

and the opportunity cost of the suppliers in the value

network) reduce the net captured value by the

service supplier.

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

88

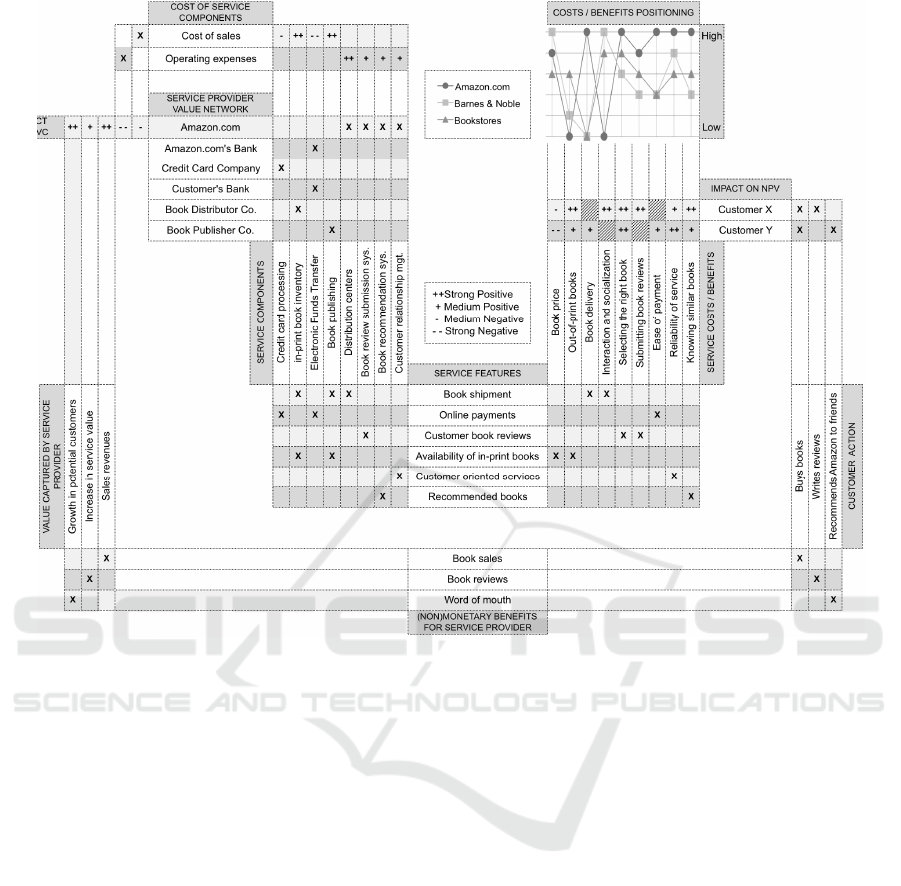

Figure 4: The overall modeling framework, including service provider value capture.

To model the service provider’s net captured

value we start our analysis from the customer side.

As discussed in Section 2.2, the customers of the

service offering take actions based on their

perceptions of the net perceived value of the service

provider relative to the competing offerings. As

illustrated in Figure 4, both Customer X and Y buy

books on Amazon.com. This action generates the

monetary benefit of “Book sales” which leads to

“Sales revenues” as the value captured by

Amazon.com. As illustrated, revenues have a strong

positive impact on Amazon.com’s net captured

value. Similarly, Customer X “Writes reviews” and

generates the non-monetary benefit of “Book

reviews” which results in an “Increase in the service

value” of Amazon.com and thereby a higher net

perceived value that can lead to more sales and

revenues. Thereby, a non-monetary benefit can lead

to the generation of monetary benefit by the passing

of time. As shown in the model “Increase in the

service value” has a medium positive impact on the

net value captured by Amazon.com. Finally,

Customer Y “Recommends Amazon.com to

friends”. The non-monetary benefit of “word of

mouth” results in “Growth in potential customers”

and a strong positive impact on Amazon.com net

captured value by the passing of time. The gray

background denotes that this impact will not occur

immediately.

To model the cost of service components, we

represent the “opportunity cost” and “organizing

cost” concepts as elaborated in Section 2.2.3, by

“cost of sales” and “operating expenses” constructs.

We define these two indicators based on the

definitions in the Amazon.com’s annual reports

1997 – 2010 (Amazon, 2011b). As our study focuses

on the book segment of Amazon.com’s business, we

modify these definitions to match the scope of our

analysis.

• Cost of sales consists of the purchase price of

the books sold by Amazon.com, inbound and

outbound shipping charges to Amazon.com,

packaging supplies, etc.

• Operating expenses comprise; marketing and

sales expenses (i.e. advertising, promotional

and public relations expenditures including the

related expenses for personnel engaged in

marketing, selling and fulfillment activities.

Modeling the Design of Value in Service-oriented Business Models

89

Product development expenses, and general

and administrative expenses (i.e. payroll and

related expenses).

As illustrated in Figure 4, we link the service

components to the cost of sales and the operating

expenses. More specifically, to represent the

organizing and opportunity costs, the service

components provided by Amazon.com are linked to

the “Operating expenses” and the service

components provided by the suppliers in

Amazon.com value network are connected to the

“Cost of sales”.

In 1997, books could be acquired from publishers

or from a network of distributors. Both the

publishers and the distributors had very high

opportunity costs. Months before publishing a book,

the publishers should determine the number of

copies they intend to print. Publishers could not

come up with an estimate before negotiating a deal

with the booksellers that grant the booksellers the

permission to return the unsold books. In 1994 for

instance, 35% of the 460 million books shipped by

the publishers were returned to them. The

distributors, on the other hand carried around

500,000 titles in their inventories to ensure they met

the demand (Spector, 2002). Moreover,

Amazon.com was also suffering from its high

organizing costs that were mainly related to

managing its huge distribution centers. In November

of 1997 Amazon.com opened up its second

distribution center. The 200,000-square-foot state-

of-the-art Delaware distribution center, the length of

three football fields, together with the expansion of

its Seattle distribution center, drastically increased

the operating expenses.

In the late 1990s, Amazon.com’s net captured

value capture had decreased, mainly due to: high

opportunity costs of publishers and distributors; high

operating expenses of its operations, and the

attributes reducing the net value perceived by its

customers (see Figure 4.). This reduction in the net

captured value had placed Amazon.com on the brink

of bankruptcy. As a matter of fact, by the summer of

2000, Amazon's stock price had dropped by more

than two-thirds and by the end of 2000, was down

more than 80% of the beginning of 2000. Wall

Street speculated that Amazon would file for

bankruptcy or that another company would buy it.

Analysts assert that if Amazon had not been able to

borrow $680 million in February of 2000, it would

have run out of cash and gone bankrupt (Applegate,

2002 and 2008).

3.4 Value Redesign in Amazon.com

Business Model Circa 2001

In November 2000, Amazon.com introduced its

new service offering, Amazon Marketplace. In the

online book value segment, Marketplace allows

bookstores to sell new, used (including out-of-print

books) on the same page that Amazon.com sells its

new books. This side-by-side placement

dramatically expanded the book selection available

to the book buyers by enabling them to choose

between new and used books from multiple

booksellers including Amazon.com on one single

store (Spector, 2002) and thereby, led to an increase

in the value perceived by the customers by

expanding the titles available.

By launching the Marketplace services,

Amazon.com put itself in a head-on price

competition with the bookstores to win over

customer orders.

Amazon Marketplace increased customer’s net

perceived value by reducing the book prices and the

availability of out-of-print books. Amazon.com and

the bookstores had to think out ways to decrease

their organizing costs so that they could offer the

book at the lowest price possible in a reverse bidding

process in order to win customer orders. This

competition resulted in a reduction in book prices on

Amazon Marketplace. In addition, the presence of

the Bookstores in Amazon Marketplace led to the

sales of used books on Amazon Marketplace that

could once more result in a lower prices and

availability of out-of-print books

Amazon Marketplace enables sellers to utilize the

e-commerce services and tools to present their

products alongside Amazon.com’s on the same

product detail page on Amazon.com’s website

pursuing what Bezos phrased as “single store

strategy”. To realize this single-store strategy, by

adapting a coopetitive (simultaneously competitive

and cooperative) strategy, Amazon.com provided

third-part sellers with automated tools to migrate

their catalogs of millions of used and out-of-print

books onto the new single product pages inside the

Amazon books tab and thereby, reducing the

bookstores’ opportunity cost by decreasing their

costs of doing business with Amazon.com. More

importantly, the Marketplace created the opportunity

for the bookstores to merchandise their products on

the highly trafficked web pages that historically had

sold only Amazon products. This, in effect, would

mean higher volume of orders and thus lower

opportunity costs for bookstores.

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

90

The Marketplace led to the generation of

significant business and thereby considerable

increase in net sales and gross profit helping

Amazon.com to offset operating expenses and sales

costs and achieve profitability in 2003 for the first

time after its establishment. The Marketplace was

the major factor behind Amazon.com’s profitability.

Amazon reported that third-party transactions

accounted for 20% of its North American units sold

in the second quarter of 2002 (Applegate, 2008).

4 RELATED WORK

e3Service (Kindern and Gordijn, 2008) is a method

for semi-automatically reasoning about matching

service offerings with service adopter needs. In

order to make this semi automatic reasoning

possible, e3Service assumes that the service adopter

and service supplier share the same ontology, that

the service adopter specifies her needs in the same

vocabulary as the service supplier specifies its

offering. We precisely avoid making this simplifying

assumption. This comes at the cost of enormously

complicating automatic or event semi-automatic

reasoning with the benefit of models that more

accurately reflect reality. Also, e3Service defines the

value of a service only from the point of view of the

service adopter.

House of Quality (Clausing and Hauser, 1988) is

an improvement method, in which the main

modeling artefact is very similar to the modeling

framework presented in this paper. The House of

Quality was derived from Quality Function

Deployment (QFD), a method that was developed by

Japanese companies to improve manufacturing

processes for greater service adopter satisfaction.

House of Quality is, therefore, more geared toward

manufacturing processes.

Strategy canvas (Kim and Mauborgne, 2004 and

2005) is a diagnostic framework for strategy

development. It allows an organization to visualize

the competitive factors and the current state of play

of those factors within a market place and to

compare the organization’s offering with those of

the industry in general.

The Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder and

Pigneur, 2010) is a strategic management tool,

which assists in the development of new and

improvement of existing business models. The

canvas includes the nine blocks of a business model:

key partners; key activities; key resources; value

propositions; customer relationships; channels, and

customer segments. While Business Model Canvas

presents all the building blocks of a business model

it does not provide a holistic view where the

interplay and the linkages between the building

blocks are modeled.

Value model in this paper is an extension to the

SAR (Supplier Adopter Relationship) diagram in

(Golnam et. al, 2010 and 2011). The SAR is a part

of the Systemic Enterprise Architecture

Methodology (SEAM) (Wegmann, 2003).

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

In this paper we proposed a modeling framework to

conceptualize and represent the design of value in

service-oriented business models. Our framework is

theoretically grounded in the theoretical insights

from management science and economics, drawing

principally upon work from the past two decades on

value creation and capture including theories,

frameworks, constructs, and other models. Thanks to

the theoretical rigour embedded our framework the

modeling artefact is generic enough to be applicable

in the representation of value design in service-

oriented business models.

We illustrated the usability and applicability of

our framework by modeling value creation and

capture in Amazon.com service system circa 1997

and gained insights into the changes that occurred in

Amazon.com’s business model circa 2001.

Future work will seek to validate and refine the

proposed model by way of applying it to an actual

firm and it’s ecosystem. In this way this research,

which has already drawn on the knowledge base for

its foundations, will draw upon the environment

(composed of people, organizations, and technology)

through its real business needs for feedback and

validation. Following this a justification and

evaluation process should take place, eventually

leading to the next iteration of the model.

REFERENCES

Afuah, A. , Tucci, C. L. 2002. Internet business models

and strategies: Text and cases, McGraw-Hill Higher

Education.

Amazon 2011a. Amazon Media Room: News Releases

http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=176060,

p=irol-news.

Amazon 2011b. Amazon.com Investor Relations: Annual

Reports and Proxies http://phx.corporate-ir.net/

phoenix.zhtml?c=97664,p=irol-reportsannual.

Modeling the Design of Value in Service-oriented Business Models

91

Ambrosini, V., Bowman, C. , Collier, N. 2010. Using

teaching case studies for management research.

Strategic Organization, 8, 206.

Applegate, L. 2002. Amazon. com: 1994-2000. Case#: 9-

801-194, Harvard Business School.

Applegate, L. M. 2008. Amazon. com: The Brink of

Bankruptcy. Harvard Business School Case, 9-809.

Barney, J. 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive

advantage. Journal of management, 17, 99.

Blomqvist, K., Kylaheiko, K. , Virolainen, V. M. 2002.

Filling a gap in traditional transaction cost

economics::: Towards transaction benefits-based

analysis. International Journal of Production

Economics, 79, 1-14.

Bowman, C. , Ambrosini, V. 2000. Value creation versus

value capture: towards a coherent definition of value

in strategy. British Journal of Management, 11,

1–15.

Brandenburger, A. M. , Stuart Jr, H. W. 1996. Value based

Business Strategy. Journal of Economics and

Management Strategy, 5, 5-24.

Carson, R. T., Flores, N. E., Martin, K. M. , Wright, J. L.

1996. Contingent valuation and revealed preference

methodologies: comparing the estimates for quasi-

public goods. Land Economics, 80-99.

Chesbrough, H., Spohrer, J., 2006. "A research manifesto

for services science," Communications of the ACM,

Vol. 49, No. 7, pp. 35-40.

Clausing, D. , Hauser, J. R. 1988. The house of quality.

Harvard Business Review, 66, 63-73.

Clulow, V., Barry, C. , Gerstman, J. 2007. The resource-

based view and value: the customer-based view of the

firm. Journal of European Industrial Training, 31, 19-

35.

Cousins, P. D. , Spekman, R. 2003. Strategic supply and

the management of inter-and intra-organisational

relationships. Journal of Purchasing and Supply

Management, 9, 19-29.

Daum, J.H., 2003. “Intangible assets and value creation”.

John Wiley & Sons.

Day, G.S., 1990. “Market Driven Strategy: Processes for

Creating Value” Journal of Marketing, vol. 55, no. 4,

pp. 116.

De Kinderen, S. , Gordijn, J. E 3 Service: A Model-Based

Approach for Generating Needs-driven E-Service

Bundles in a Networked Enterprise. Proceedings of the

16th European Conference on Information Systems

(ECIS), Galway, Ireland, 2008.

Dierickx, I., Cool, K., 1989. “Asset stock accumulation

and sustainability of competitive advantage,”

Management science, pp. 1504–1511.

Eggert, A., Ulaga, W., 2002. “Customer perceived value: a

substitute for satisfaction in business markets?,”

Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, vol. 17,

no. 2/3, pp. 107-118.

Freel, M. 2006. Patterns of technological innovation in

knowledge intensive business services. Industry and

Innovation, 13, 335-358.

Golnam, A., Regev, G., Ramboz, J., Laparde, P. ,

Wegmann, A, 2010. Systemic Service Design:

Alaigning Value with Implementation. In: Snene, M.,

Ralyté, J. & Morin, J.-H., eds. 1st International

Conference on Exploring Services Sciences, Geneva,

Switzerland. Springer, 150-164.

Golnam, A., Regev, G., Ramboz, J., Laprade, P. ,

Wegmann, A, 2011. Aligning Value and

Implementation in Service Design - A Systemic

Approach. International Journal of Service Science,

Management, Engineering, and Technology

(IJSSMET), In Press.

Golnam, A., Ritala, P., Viswanathan, V., Wegmann, A,

2012. Modeling Value Creation and Capture in

Service Systems. In: SNENE, M., ed. Third

International Conference on Exploring Services

Sciences, February 2012 Geneva, Switzerland.

Springer, 155-169.

Gordijn, J. , Akkermans, J. 2003. Value-based

requirements engineering: Exploring innovative e-

commerce ideas. Requirements Engineering, 8, 114-

134.

Gordijn, J., Yu, E. , Van Der Raadt, B. 2006. E-service

design using i* and e 3 value modeling. IEEE

software, 23, 26-33.

Grant, R. M. 1996. Toward a knowledge-based theory of

the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109-122.

Grönroos, C., 2000. “Service Management and

Marketing” European Journal of Marketing, vol. 15,

no. 2, pp. 3-31.

Grönroos, C. , Ravald, A. 2011. Service as business logic:

implications for value creation and marketing. Journal

of Service Management, 22, 5-22.

Heck, E. , Vervest, P. 2007. Smart business networks: how

the network wins. Communications of the ACM, 50,

28-37.

Jacobides, M.G., Knudsen, T., Augier, M., 2006.

“Benefiting from innovation: Value creation, value

appropriation and the role of industry architectures,”

Research Policy, vol. 35, no. 8, pp. 1200-1221.

Johannesson, P., Andersson, B., Bergholtz, M. , Weigand,

H. 2009. Enterprise modelling for value based service

analysis. The Practice of Enterprise Modeling, 153-

167.

Kalpanik, S. , Zheng, C. 2011. Inside the Giant Machine -

An Amazon.com Story, Center of Artificial

Imagination, Inc. 2nd Edition.

Khalifa, A.S., 2004. “Customer value: a review of recent

literature and an integrative configuration,”

Management Decision, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 645-666.

Kim, W. C. , Mauborgne, R. 2004. Blue ocean strategy. If

you read nothing else on strategy, read thesebest-

selling articles., 71.

Kim, W. C. , Mauborgne, R. E. 2005. Blue Ocean

Strategy: How to Create Uncontested Market Space

and Make Competition Irrelevant, Harvard Business

Press.

Kothandaraman, P. , Wilson, D. T. 2001. The Future of

Competition:: Value-Creating Networks. Industrial

Marketing Management, 30, 379-389.

Kotler, P. 2000. Marketing management, millennium ed.

Second International Symposium on Business Modeling and Software Design

92

Lepak, D., Smith, K., Taylor, M., 2007. “Introduction to

Special Topic Forum: Value Creation and Value

Capture: A Multilevel Perspective,” The Academy of

Management Review ARCHIVE, vol. 32, no. 1, pp.

180-194.

Masten, S. E., Meehan, J. W. , Snyder, E. A. 1991. The

costs of organization. Journal of Law, Economics, and

Organization, 7, 1.

Moller, K. , Svahn, S. 2006. Role of Knowledge in Value

Creation in Business Nets*. Journal of Management

Studies, 43, 985-1007.

Norman, R. , Ramirez, R. 1993. From Value Chain to

Value Constellation. Harvard Business Review, 71,

65-77.

Osterwalder, A. , Pigneur, Y. 2010. Business model

generation: A handbook for visionaries, game

changers, and challengers, Wiley.

Peppard, J., Rylander, A., 2006. “From Value Chain to

Value Network:: Insights for Mobile Operators,”

European Management Journal, vol. 24, no. 2-3, pp.

128-141.

Pijpers, V. , Gordijn, J. 2007. e 3 forces : Understanding

Strategies of Networked e 3 value Constellations by

Analyzing Environmental Forces. Advanced

Information Systems Engineering.

Pitelis, C. N. 2009. The co-evolution of organizational

value capture, value creation and sustainable

advantage. Organization Studies, 30, 1115.

Ritala, P., Andreeva, T., Kosonen, M. , Blomqvist, K.

2011. A Problem-Solving Typology of Service

Business. Electronic Journal of Knowledge

Management, 9, 37-45.

Ritala, P., Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P. 2009. What's in it

for me? Creating and capturing value in innovation-

related coopetion. Technovation, 29, 819-828.

Spector, R. 2002. Amazon. com: Get big fast, Harper

Paperbacks.

Stake, R. E. 1995. The art of case study research, Sage

Publications, Inc.

Teece, D. J. 2009. Dynamic capabilities and strategic

management: organizing for innovation and growth,

Oxford University Press, USA.

Tether, B. S. , Hipp, C. 2002. Knowledge intensive,

technical and other services: patterns of

competitiveness and innovation compared. Technology

Analysis and Strategic Management, 14, 163-182.

Vargo, S. L. , Lusch, R. F. 2004. Evolving to a new

dominant logic for marketing. Journal of marketing,

68, 1‚17.

Vargo, S. L. , Lusch, R. F. 2008. Service-dominant logic:

continuing the evolution.

Journal of the Academy of

Marketing Science, 36, 1.

Vargo, S. L., Maglio, P. P. , Akaka, M. A. 2008. On value

and value co-creation: A service systems and service

logic perspective. European Management Journal, 26,

145–152.

Weigand, H. 2009. Value Encounters: Modeling and

Analyzing Co-creation of Value. Software Services for

e-Business and e-Society, 51-64.

Weigand, H., Johannesson, P., Andersson, B. , Bergholtz,

M. Value-based service modeling and design: Toward

a unified view of services. 2009. Springer, 410-424.

Yin, R. K. 2009. Case study research: Design and

methods, Sage Publications, Inc.

Yu, E. 1997a. Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE International

Symposium on Requirements Engineering. Citeseer.

Yu, E. S. K. 1997b. Towards modelling and reasoning

support for early-phase requirements engineering.

Requirements Engineering, 1997., Proceedings of the

Third IEEE International Symposium on.

Modeling the Design of Value in Service-oriented Business Models

93