Managing the Process Conglomeration in Health and Social Care

Monica Winge, Paul Johannesson, Erik Perjons and Benkt Wangler

Department of Computer and Systems Sciences, Stockholm University, Forum, SE-164 40, Kista, Sweden

Keywords: Process Conglomeration, Patient Care Process, Coordination Theory, Speech Act Theory, Information

Services.

Abstract: The organisation and processes of today’s health and social care are becoming ever more complex as a

consequence of societal trends, including an ageing population and an increased reliance on care at home.

One aspect of the increased complexity is that a single patient may receive care from several separate care

providers, which easily results in situations with potentially incoherent, uncoordinated and interfering care

processes. In order to describe and analyse such situations, the paper introduces the notion of a process

conglomeration. This is defined as a set of patient care processes that all influence the same patient, which

are overlapping in time, and that all have the goal of improving or maintaining the health and social

wellbeing of the patient. Problems and challenges of process conglomerations are investigated using

coordination theory and speech act theory. In order to address the challenges, a number of information

services are proposed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Today’s health and social care systems face a

number of challenging trends that contribute to their

increased complexity. One trend is that the

population in developed countries is ageing meaning

that more and more people are suffering from

multiple diseases. Many patients are being cared for

in their homes due to both individual preferences

and needs for cost containment. This adds to

complexity as health and social care at home

typically requires that many care providers with

different specialities are involved, private as well as

public ones. Not only health care is required but also

social care with assistance for daily living.

Furthermore, informal care parties like family

members and neighbours also get a more prominent

role for support and mediation.

In this complex and patient centered care

environment, multiple care parties are hence

engaged in concurrent and asynchronous processes

for assisting, investigating and treating a patient. The

complex environment results in situations where

care is provided through an aggregation of

potentially incoherent, uncoordinated and interfering

processes. In order to represent and analyse these

emergent aggregations of processes, we introduce

the notion of a process conglomeration that consists

of separate and more or less independent care

processes. In a process conglomeration, the patient

may experience problems like several care parties

visiting at the same time, different care parties

prescribing conflicting treatments, or care parties

neglecting their responsibilities.

Most work on business process management in

health care has focused on improving organisational

performance, medical effectiveness, knowledge

exchange and information system integration (e.g.,

Lenz and Reichert, 2007; Walburg, 2006; Beveren,

2003). However, to the best of our knowledge, the

research literature has as yet not paid any attention

to the problems that arise when several similar,

interdependent and concurrently ongoing business

processes are entangled in what we here refer to as a

process conglomeration.

In order to overcome the problems and

challenges of process conglomerations, multiple

complementing solutions are needed. Some

solutions aim at improving organisational structures

and processes, while others focus on attitudes and

behaviours among personnel. There are also

solutions that address reimbursement models and

incentive structures. In this paper, we focus on

information and communication solutions that

enable multiple care parties and patients to

coordinate their activities. A main goal of the paper

374

Winge M., Johannesson P., Perjons E. and Wangler B..

Managing the Process Conglomeration in Health and Social Care.

DOI: 10.5220/0004248903740381

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2013), pages 374-381

ISBN: 978-989-8565-37-2

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

is to propose a set of information services that, in the

context of process conglomerations, can facilitate

effective and seamless communication between

health care parties.

2 THEORETICAL BASIS

2.1 Language Action Perspective

A common view on business processes is that they

transform inputs into outputs. The activities of a

process are seen as contributing to more value for a

customer as inputs are successively refined into

outputs. However, as noted by Goldkuhl and Lind

(2008), this view may be too restrictive as it

disregards the coordinative aspects of business

processes. From a coordination perspective, a

business process focuses not on value

transformations but on communicative acts like

requests, offers, counteroffers, commitments,

agreements, acknowledgments, etc. The theoretical

foundations of this view come primarily from speech

act theory, (Searle, 1970). A basic idea in speech act

theory is that people carry out social activities (also

called speech acts) that, if properly combined and

executed, result in social relationships. For example,

a request (social activity) followed by a commitment

(social activity) will result in a contract (social

relationship) between two actors.

One influential approach to a communicative

view on business processes is the action workflow

loop (Winograd and Flores, 1987), see Figure 1. The

loop consists of four parts:

Request. One party requests another party to

carry out some activity.

Commitment. After an optional negotiation, the

party who received a request for an activity may

commit to carry it out. This results in an

agreement, a social relationship, between the

two parties that one of them is to carry out an

activity for the benefit of the other.

Execution. The party who committed to carry

out an activity actually executes it.

Acknowledgement. The requesting party

acknowledges the execution of the activity and

confirms that she is satisfied with it.

2.2 Coordination Theory

In order to work smoothly, processes need to be

coordinated. Malone and Crowston (1990) suggest

the following definition of coordination: “the act of

Request

Commitment

ExecutionAcknowledgement

Figure 1: The action workflow loop.

managing interdependencies between activities

performed to achieve a goal”. Such dependencies

may give rise to conflicts and need to be detected

and resolved. There are three main kinds of activity

dependencies:

Flow Dependencies. A flow dependency

between two activities occurs when one of the

activities needs to be carried out before the

other one, often because the first activity

produces some resource required by the other

one.

Share Dependencies. A share dependency

occurs when two activities try to get exclusive

access to the same resource at the same time.

An example is that two physicians want to use

the same X-ray machine at the same time, or

simply that two actors need to get access to a

patient at the same time.

Fit Dependencies. A fit dependency occurs

when two activities modify the same resource

and need to ensure that the modifications are

consistent and coherent, taking into account the

overall needs and constraints of the resource.

An example is that a patient is given two drugs

that interfere with each other.

3 THE PROCESS

CONGLOMERATION

CHALLENGE

This section introduces the notion of process

conglomerations as well as the challenges they give

rise to. Before addressing these issues we introduce

some basic concepts for the actors involved in health

care, see Figure 2. These concepts are based on

(CONTSYS, 2007) and (Gustafsson and Winge,

2003).

A health/social care party (sometimes

abbreviated care party) is a person or organisation

that is involved in health/social care. There are three

kinds of care parties: health/social care provider,

health/social care third party, and patient. A

health/social care provider (sometimes abbreviated

ManagingtheProcessConglomerationinHealthandSocialCare

375

Health/social

care provider

Health/social

care party

Health/socialcare

organisation

Health/socialcare

professional

Health/social

care third party

Patient

Figure 2: Basic concepts for actors involved in health care.

care provider) is a person or organisation that

provides health/social care. A health/social care

third party (sometimes abbreviated carer) is a

person or organisation that supports care services

and is not a professional health/social care party. An

example could be a relative to a patient that

performs some or all care activities needed for

taking care of the patient. A patient is a care party

that receives or can receive health/social care.

Finally, a care provider can be of two kinds:

health/social care organisation and health/social care

professional. A health/social care organisation

(sometimes abbreviated care organisation) is a

private or public organisation that provides care as

its main service, while a health/social care

professional is a person that in her professional role

provides care.

The work carried out by one care provider for

one patient can be described as an action workflow

loop, see Figure 3, which we refer to as the Patient

Care Process. It contains the following activities:

Request. A care provider receives a request

from a care party to address a health/social

problem for a patient.

Negotiation. The care provider commits to

address the care request.

Execution. The care provider together with the

patient set up a plan including a set of goals and

activities that aims to improve the patient’s

health/social situation. The care provider then

performs the planned activities.

Acknowledgment. Finally, the requester

evaluates goal fulfilment.

Request

Commitment

ExecutionAcknowledgement

• Receive care

request

• Confirm care

commitment

• Determine

health/social

problem

• Decide care goals

• Specify care plan

• Performcare

activities

• Evaluate goal

fulfillments

Figure 3: The patient care process described as a workflow

loop.

While Figure 3 provides an overview of the Patient

Care Process, Figure 4 describes it in greater detail.

This model is based on the patient care processes

described in SAMBA (Samba, 2004) and SAMS

(Winge, 2007), though adapted for the purpose of

addressing process conglomerations.

The detailed Patient Care Process (described in

Figure 4) contains the following activities:

Request. The Patient Care Process starts when a

care provider receives a care request from a

care party.

Negotiation. The receiving care provider checks

Receive

care request

Confirm

care commitment

Specify care

plan

Evaluate goal

fulfillments

Send care request

foractivity

Receive care

commitment foractivity

Isthere an

activityin

theplan

thatisstill

left tobe

carried out ?

Yes

Receive activity

completion

No

Isthe

activity

decided to

becarried

out inthe

organisa‐

tion?

Yes

No

Schedule

activity

Perform

activity

Identify health/

socialstatus

Determine health/

socialproblem

Decide care

goals

Figure 4: The Patient Care Process described in more detail.

HEALTHINF2013-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

376

that it is able to take responsibility for the care

request. If so, it confirms a care commitment.

Execution - planning level. The responsible care

provider identifies the patient’s health/social

status, i.e., anamnesis, symptoms and earlier

treatments, and determines the patient’s

health/social problems. Thereafter, a care plan

is to be specified. This can often be done by the

responsible care provider and the patient

themselves, but it sometimes requires a planning

conference, in which several care parties

participate.

Execution - performance level. Each activity in

the care plan needs to be performed by either

the responsible care provider or another actor. If

the activity is performed by the responsible care

provider, it will both schedule the activity and

then perform the activity. If the activity is to be

performed by another actor, a care request is

sent to this actor asking it to be responsible for

the activity.

Acknowledgment. Finally, when all the activities

in the care plan have been carried out, the

responsible care provider evaluates the goal

fulfillment of the care plan. This includes an

acknowledgement from the original requester

that the care plan has been executed as well as a

confirmation or refutation that the patient’s

health/social situation has been improved.

A patient is often involved in several processes, as a

patient care process can be nested within another as

a consequence of a care provider outsourcing some

activities. In addition to several processes being

nested due to activities being outsourced from one

care provider to another, a patient can also be

subject to a number of more or less independent care

processes, each conducted by separate care parties.

The reason may be that the patient suffers from and

is treated for multiple health/social problems.

A set of independent care processes around a

patient will form a process conglomeration, see

Figure 5, which includes activities that are

potentially incoherent, uncoordinated and

interfering. More precisely, we define a process

conglomeration as a set of patient care processes

that all influence the same patient, which are

overlapping in time, and that all have the goal of

improving or maintaining the health and social

wellbeing of the patient.

Process conglomerations give rise to

coordination problems that go beyond those

encountered in single or nested patient care

processes. A key difference between single patient

care processes and conglomerations is that the

activity dependencies in a patient care process are

PATIENT

Figure 5: A process conglomeration, i.e., a set of

individual though interdependent care processes around a

patient.

planned and known beforehand, while those in a

conglomeration are emergent and may occur

unexpectedly for the involved care parties. While

each patient care process is internally coordinated in

the form of an action workflow loop with a clear

structure and distribution of responsibilities, there is

no corresponding coordination across the care

processes in a process conglomeration. Thus,

dependencies between activities from different

patient care processes may easily be neglected,

which may cause worries and inconveniences for the

patient as well as ineffective and inefficient care.

Furthermore, as many parties are involved in a

process conglomeration, responsibility issues may

arise.

As a process conglomeration can be highly

complex, problems can easily occur if it is not

adequately managed. Based on coordination theory

and previous work in Gustafsson and Winge (2003)

and Centrum för e-Hälsa (2007), we have identified

four main categories of problems in a process

conglomeration.

Share Negligence. Two or more care parties try

to provide care to a patient at the same time. In

other words, the parties try to carry out activities

between which there exists a share dependency.

For example, a patient may be busy with her

physiotherapist when a nurse shows up to

plaster a leg ulcer.

Flow Negligence. Two care parties carry out

activities in the wrong order. In other words,

there is a flow dependency between activities

that is not respected by the care parties. For

example, a nurse first plasters the leg ulcer of a

patient, and thereafter the home care personnel

give the patient a shower, while these activities

ought to be carried out in the opposite order.

ManagingtheProcessConglomerationinHealthandSocialCare

377

Fit Negligence. Two activities are carried out

though they may conflict with each other. In

other words, there is a fit dependency between

activities that is not respected. For example, a

patient is given a therapy by a physiotherapist

that is not suitable for a certain medical

treatment given by a nurse from primary care.

Responsibility Negligence. A health care party

who is responsible for a task does not carry it

out or carries it out in an unsatisfactory way.

For example, a nurse may not distribute

prescribed medication to a patient, though this is

her responsibility.

The underlying causes to these problems may vary,

including deficiencies in organisational structures

and gaps in personnel competence. However, in a

process conglomeration, a main cause for the

problems is lack of information, knowledge and

common views due to inadequate communication.

Based on the activities of the Patient Care Process as

well as previous work by Gustafsson and Winge

(2003), we have identified four categories of

knowledge deficiencies that cause problems in

process conglomerations.

Lack of knowledge about the health/social

problems and health/social status of patients

Lack of knowledge about performed, ongoing

and planned activities as well as activity

dependencies and changes in plans

Lack of knowledge and consensus on care goals

and their priorities

Lack of clearly allocated responsibilities and

knowledge about them.

4 SOLUTION REQUIREMENTS

The information and communication problems of

process conglomerations can be addressed by

providing care parties with information services that

support them in exchanging information, building

consensus and distributing responsibilities. This

section identifies a number of requirements that

these services need to fulfil in order to effectively

address the problems. The requirements below are

structured according to the problem causes they

address.

Lack of knowledge about the health/social problems

and health/social status of patients

R1: Care providers shall be able to exchange their

assessments on the health/social problems of a

patient

R2: Care providers shall receive support for

detecting, discussing and negotiating differences in

their assessments of the health/social problems of

patient

R3: Care parties shall be able to communicate about

the health/social status of a patient

Lack of knowledge about performed, ongoing and

planned activities as well as activity dependencies

and changes in plans

R4: Care parties shall be able to communicate about

care activities planned to be carried out

R5: Care parties shall be able to request care from

other care parties as well as commit to carry out care

R6: Care parties shall be able to communicate

ongoing and completed care activities

R7: Care parties shall be able to communicate about

the results of care activities

R8: Care parties shall receive support for detecting

and managing activity dependencies

Lack of knowledge and consensus on care goals and

their priorities

R9: Care parties shall be able to communicate about

the goals for activities carried out by care providers

R10: Care parties shall receive support for detecting

and managing care goal conflicts

Lack of clearly allocated responsibilities and

knowledge about them

R11: Care parties shall be able to communicate

about the responsibilities of care providers

R12: Care parties shall receive support for detecting

and managing responsibility negligence

As can be seen from the above requirements, the

information services need to handle complex

information structures. A first step towards defining

the services is, therefore, to construct an information

model that can represent all the information needed

by the services.

5 SOLUTION - INFORMATION

MODEL AND INFORMATION

SERVICES

A solution to the process conglomeration challenge

is suggested in this section in the form of a number

of information services, see Section 5.2. First, in

HEALTHINF2013-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

378

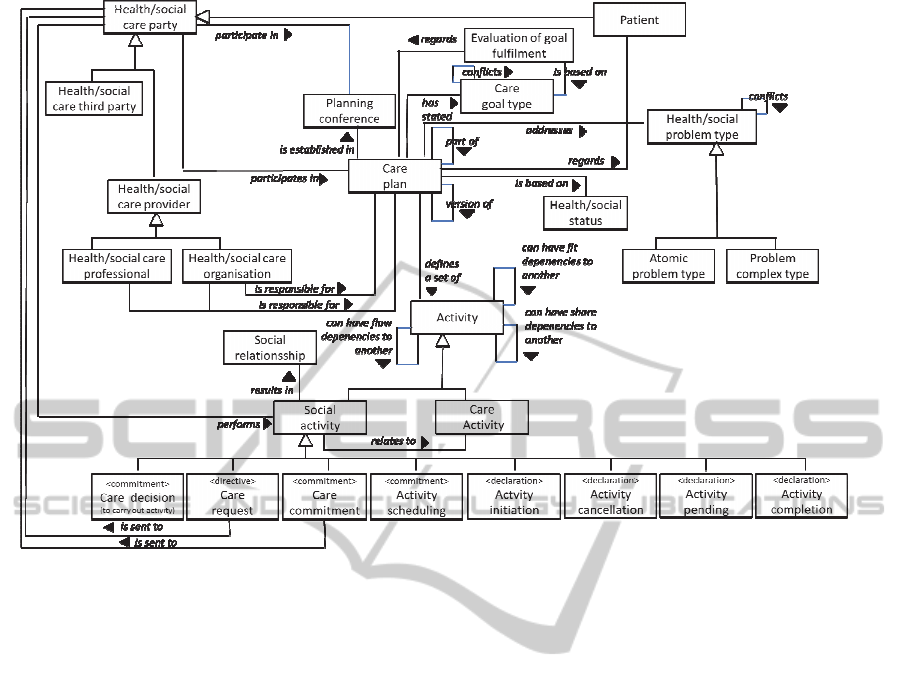

Figure 6: An information model that represents all the information needed by the services.

section 5.1, an underlying information model is

presented, which can represent all the information

needed by the services.

5.1 Information Model

The proposed information model, which is based on

(CONTSYS, 2007) and (Gustafsson and Winge,

2004), is described below and shown as a UML

class diagram in Figure 6. The first group of

requirements in Section 4 demands that the

information services be able to manage information

about the health/social problems and health/social

status of patients. To handle this, the information

model includes the classes health/social problem

type (sometimes abbreviated health problem) and

health/social status (sometimes abbreviated health

status). A health/social care problem type is a need

for care for a patient as defined by a care provider,

often expressed as a diagnosis. A health/social

problem type is either an atomic problem type or a

combination of problem types, called problem

complex type. The latter notion is useful as patients

often experience a number of related health/social

problems, which can be effectively addressed by the

same care plan. The information model also includes

the class health/social status, which contains a

description of a patient’s anamnesis, symptoms and

earlier treatments when a care plan is established.

The second group of requirements in Section 4

demands that the information services be able to

manage information about activities and activity

dependencies. To handle this, the information model

includes the class care plan. A care plan can be a

part of or a version of another care plan. To establish

the care plan, there is sometimes a need for a

planning conference, which can be carried out

synchronously or asynchronously as well as at a

central place or in a distributed way. To represent

activity dependencies, the information model

includes associations for flow dependency, fit

dependency and share dependency.

The third group of requirements demands that

the information services be able to manage

information on care goals. To handle this, the

information model includes the class care goal type,

which is a set of predefined goals. To represent goal

conflicts, the information model includes an

association called conflicts. Each plan has one or

several of these goals related to it. The information

model is also able to represent the evaluation of the

goal fulfillment of the plan, that is, the result of a

performed care plan.

The fourth group of requirements demands that

the information services be able to manage

information about responsibility allocation. A care

ManagingtheProcessConglomerationinHealthandSocialCare

379

activity is a clinical activity that aims to investigate

or treat a patient. Around a care activity, various

care parties take a number of decisions that can be

seen as driving the care activity forwards. For

example, one care party can decide that a certain

care activity is to be carried out, and another care

party can decide to actually carry it out.

In order to represent decisions about care

activities, we introduce a class social activity. A

social activity, as described in Section 2.1, is a

sequence of speech acts that results in one or several

social relationships. There exist a number of

subclasses to social activity:

A care decision is a decision taken by a care

professional that a certain care activity is to be

carried out.

A care request is a social activity where one

care party asks another care party to take on the

responsibility for a care activity.

A care commitment is a commitment by a care

party, who has received a care request and that

takes on the responsibility for the care activity.

An activity scheduling includes a commitment

by a care party to start carrying out a care

activity at a time point.

An activity initiation includes a declaration by a

care party that a care activity has started.

An activity cancellation includes a declaration

that a care activity has been aborted before

completion and that no further work is planned.

An activity pending includes a declaration that a

care activity has been aborted before completion

as well as a commitment that it is to be

restarted.

An activity completion includes a declaration

that a care activity has been completed as

intended.

5.2 Information Services

Five high level services are identified, based on the

activities of the patient care process, and for each of

these a number of sub-services. For each sub-

service, its relationship to the information model is

specified and the requirements (R) it addresses.

Identify Health/Social Status and Determine

Health/Social Problem

This service provides support for communicating

about care need assessments. The included sub-

services are:

● Create, read and update health/social status

and health/social problem (R1, R3)

● Notify about conflicting views of

health/social problem among care parties

(R2)

Decide Care Goals

This service provides support for communicating

about care goal creation. The included sub-services

are:

● Create, read and update care goals (R9)

● Notify about about conflicting views of

care goals among care parties (R10)

Specify Care Plan

This service provides support for communicating

and negotiating care planning. The included sub-

services are:

● Create, read and update care plans, care

activities, care decisions, care requests and

care commitments (R4, R5, R11)

● Notify about activity dependencies that

occur when creating new care decisions and

care plans (R8)

● Support resolution of conflicts due to

activity dependencies (R8)

● Check for outstanding care decisions, i.e.,

care decisions for which there are as yet no

care requests (R12)

● Check for outstanding care requests, i.e.,

care requests for which there are as yet no

care commitments (R12)

Schedule and Perform Care Activity

This service provides support for communicating

about and managing the performance of care

activities. The included sub-services are:

● Create, read and update activity initiations,

activity cancellations, activity pendings,

and activity completions (R6)

● Notify about activity dependencies that

occurred when care activities were initiated

or completed (R8)

● Check for outstanding activity schedulings,

i.e. activity schedulings for which there are

as yet no activity initiations (R12)

Care Evaluation

This service provides support for communicating

about care evaluation. The included sub-services are:

● Create, read and update evaluations of goal

fulfilment (R7)

6 CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this paper, we have investigated how care

activities and processes are organised in today’s

complex and patient centered health and social care

HEALTHINF2013-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

380

landscape. The main theoretical contribution of the

paper is the introduction of the notion of process

conglomeration, which is used to capture the

emergent nature of health care provisioning in an

environment of independent care parties. The paper

also provides practical contributions through an

analysis of the challenges posed by process

conglomerations as well as solutions in the form of

information services.

The proposed information services are based on

the assumption that care activities offered by one

care provider can be structured according to the

patient care process, basically an action workflow

loop. The patient care process structures the internal

work of a care provider and its interactions with a

patient, thereby producing a large amount of

information. This constitutes the bulk of the

information needed by the proposed information

services. Thus, implementing the services does not

require extensive additional information

management for care providers that already use the

patient care process.

Our work has been carried out according to the

design science framework, which is also reflected by

the structure of the paper that follows the methods

proposed by Peffers et al. (2007). While this paper

focuses on problem analysis, requirements definition

and solution design, previous work has addressed

demonstration and evaluation of the services.

In future work, we will detail the contents of the

information services and integrate them into an

overarching systems and service architecture. We

will also continue our work on empirical validation

of this architecture.

REFERENCES

Beveren, J. Van, 2003. Does health care for knowledge

management? In Journal of Knowledge Management,

7 (1): 90 – 95.

Centrum för för eHälsa, 2007. IT-implementering i vård

och omsorg: Slutrapport 2007-12, Centrum för eHälsa

(in Swedish)

CONTSYS, 2007. Health Informatics – Systems of

concepts to support continuity of care. Part 1: Basic

Concepts, EN-13940-1:2007.

Goldkuhl, G., and Lind, M., 2008. Coordination and

transformation in business processes: towards an

integrated view. In Business Process Management

Journal, 14 (6): 761–777.

Gustafsson, M., and Winge, M., 2003. SamS-projektet:

Process- och begreppsmodellering – delrapport (in

Swedish).

Gustafsson M., Winge M., 2004. SAMS Konceptuell

Informationsmodell – delrapport (in Swedish).

Lenz, R., and Reichert, M., 2007. IT support for healthcare

processes - premises, challenges, perspectives. In Data

and Knowledge Engineering 61: 39-58.

Malone, T.W., and Crowston, K., 1990. What is

coordination theory and how can it help design

cooperative work systems? In Proceedings of the 1990

ACM conference on Computer-supported cooperative

work, New York, NY, USA, pp. 357–370.

Peffers, K., Tuunanen, T., Rothenberger, M.A., and,

Chatterjee, S., 2007. A Design Science Research

Methodology for Information Systems Research. In

Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(3):

45-78.

SAMBA, 2004. Structured Architecture for Medical

Business Activities. Available (2012-09-03) at:

http://www.contsys.net/documents/samba/samba_en_s

hort_1_3.pdf.

Searle, J.R., 1970. Speech Acts: An Essay in the

Philosophy of Language, Cambridge University Press

Walburg, J., 2006. The outcome quadrant. In Walburg, J.,

Bevan, H., Wilderspin, J., and Lemmens, K. (eds.)

Performance Management in Health Care. Improving

patient outcomes: an integrated approach, Routledge..

Winograd, T. and Flores, F., 1987. Understanding

Computers and Cognition: A New Foundation for

Design. Addison-Wesley Professional

Winge., M., Johansson, L.-Å., Gustafsson, M., Fors, U.,

Lind Waterworth, E., and Sarv-Strömberg, L., 2007.

Slutrapport MobiSams-projektet: Mobilt IT-stöd för

samverkan i vård och omsorg.

ManagingtheProcessConglomerationinHealthandSocialCare

381