Effects of Mid-term Student Evaluations of Teaching as Measured

by End-of-Term Evaluations

An Emperical Study of Course Evaluations

Line H. Clemmensen

1

, Tamara Sliusarenko

1

, Birgitte Lund Christiansen

2

and Bjarne Kjær Ersbøll

1

1

Department of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science, Technical University of Denmark, Richard Petersens Plads,

Lyngby, Denmark

2

LearningLab DTU, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark

Keywords: End-of-Term Evaluations, Midterm Evaluations, Student Evaluation of Teaching.

Abstract: Universities have varying policies on how and when to perform student evaluations of courses and teachers.

More empirical evidence of the consequences of such policies on quality enhancement of teaching and

learning is needed. A study (35 courses at the Technical University of Denmark) was performed to illustrate

the effects caused by different handling of mid-term course evaluations on student’s satisfaction as

measured by end-of-term evaluations. Midterm and end-of-term course evaluations were carried out in all

courses. Half of the courses were allowed access to the midterm results. The evaluations generally showed

positive improvements over the semester for courses with access, and negative improvements for those

without access. Improvements related to: Student learning, student satisfaction, teaching activities, and

communication showed statistically significant average differences of 0.1-0.2 points between the two

groups. These differences are relatively large compared to the standard deviation of the scores when student

effect is removed (approximately 0.7). We conclude that university policies on course evaluations seem to

have an impact on the development of the teaching and learning quality as perceived by the students and

discuss the findings.

1 INTRODUCTION

For decades, educational researchers and university

teachers have discussed the usefulness of, as well as

the best practice for student evaluations of teaching

(SET). To a large extent discussions have focused on

summative purposes like the use of SETs for

personnel decisions as recruitment and promotion

(Oliver and Sautter 2005; McKeachie, 1997; Yao

and Grady, 2005). The focus in the present study is

the formative aspect, i.e. the use of SETs to improve

the quality of teaching and learning.

Much effort has been put into investigating if

SETs give valid measurements of teaching

effectiveness with students’ learning outcome as the

generally accepted – though complex to measure –

core factor (see metastudies of Wachtel, 1998, and

Clayson, 2009). Though SETs can be questioned to

be the best method for measuring teaching

effectiveness (Yao and Grady, 2005), there is a

general agreement that it is the most practical and to

some extent valid measure of teaching effectiveness

(Wachtel, 1998). Additionally, SETs provide

important evidence that can be used for formative

purposes (Richardson, 2005).

Studies of the long-term effect of SETs tend to

lead to the discouraging conclusion that no general

improvement takes place over a period of 3-4 years

or more (Kember et.al., 2002; Marsh and Hocevar,

1991). However, it is generally found that when the

feedback from SETs is supported by other steps,

such as consultations with colleagues or staff

developers, or by a strategic and systematic

approach to quality development at university level,

improvements can be found according to the SET

results (Penny and Coe, 2004; Edström, 2008).

Some attention has also been directed to the

timing of the evaluations – midterm, end-of-term,

before or after the exam (Wachtel, 1998). There is

some evidence that evaluation results depend on

whether they were gathered during the course term

or after course completion (Clayson, 2009;

Richardson, 2005).

Keeping the formative aim in mind, it is of

303

H. Clemmensen L., Sliusarenko T., Lund Christiansen B. and Kjær Ersbøll B..

Effects of Mid-term Student Evaluations of Teaching as Measured by End-of-Term Evaluations - An Emperical Study of Course Evaluations.

DOI: 10.5220/0004353503030310

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2013), pages 303-310

ISBN: 978-989-8565-53-2

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

interest whether midterm evaluations can lead to

improvement within the semester to meet the needs

of the students in a specific class context (Cook-

Sather, 2009). In a meta-analysis of a number of

studies comparing midterm and end-of-term SET

results, Cohen (1980) concluded that on average the

mid-term evaluations had made a modest but

significant contribution to the improvement of

teaching. His analysis confirms findings from other

studies that the positive effect is related to

augmentations of the feedback from students –

typically consultations with experts in teaching and

learning (Richardson, 2005; Penny and Coe, 2004).

In Denmark as in other Nordic countries, the

general use of course evaluations has a shorter

history. SETs have primarily been introduced for

formative purposes as well as an instrument for the

institution to monitor and react on student

satisfaction in general and on specific issues (e.g.

teachers’ English proficiency). As an effect of a

requirement from 2003, all Danish universities make

the outcome of course evaluations public (Andersen

et al., 2009). Thus, key results of the existing SET

processes are also used to provide information to

students prior to course selections.

At the Technical University of Denmark, average

ratings of answers to closed questions related to the

course in general are published on the university’s

web site. Ratings of questions related to individual

teachers and answers to open questions are not

published. The outcome is subject to review in the

department study board that may initiate follow-up

actions.

As an extensive amount of time and effort is

spent on the evaluation processes described, it is of

vital interest to examine whether the processes could

be improved to generate more quality enhancement.

Therefore, the present study provides a basis to

consider whether mid-term course evaluations can

be used as a supplement to (or partial substitution of)

end-of-term evaluations to create an immediate

effect on quality of teaching and learning in the

ongoing course.

In the study, the student evaluations are treated

as a source of information on the teaching and

learning process, as perceived by the students, which

can be used as a basis for improvements. An

experimental setup is designed to address the

question: What is the effect of mid-term course

evaluations on student’s satisfaction with the course

as measured by end-of-term evaluations?

The study addresses how general university

policies can influence the quality of courses by

deciding when to perform student evaluations.

Therefore, the course teachers were not obliged to

take specific actions based on the midterm

evaluations.

The paper is organized as follows. The

experimental design is explained in Section 1.

Section 2 gives the methods of analysis, and Section

3 the results. Section 4 discusses the findings, and

we conclude in Section 5.

2 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Since 2001 standard student evaluations at the

Technical University of Denmark are performed

using an online questionnaire posted on

“CampusNet” (the university intra-net) as an end-of-

term evaluation in the last week of the semester

(before the exams and the grades are given). The

semesters last thirteen weeks. On one form the

student is asked questions related to the course in

general (Form A) and on another form questions

related to the individual teacher (Form B). The

questions can be seen in Table 1. The students rate

the questions on a 5 point Likert scale (Likert, 1932)

from 5 to 1, where 5 corresponds to the student

“strongly agreeing” with the statement and 1

corresponds to the student “strongly disagreeing”

with the statement. For questions A.1.6 and A.1.7, a

5 corresponds to “too high” and 1 to “too low”. In a

sense for these two questions a 3 corresponds to

satisfactory and anything else (higher or lower)

corresponds to less satisfactory. Therefore the two

variables corresponding to A.1.6 and A.1.7 were

transformed, namely: 5-abs(2x-6). Then a value of 5

means “satisfactory” and anything less means “less

satisfactory”. Furthermore, the evaluations contain

three open standard questions “What went well –

and why?”, “What did not go so well – and why?”,

and “What changes would you suggest for the next

time the course is offered?” Response rates are

typically not quite satisfactory (a weighted average

of 50%). However, they correspond to the typical

response rates for standard course evaluations. The

results are anonymous when presented to teachers

while they in this study were linked to encrypted

keys in order to connect a student’s ratings from

midterm to end-of-term.

A study was conducted during the fall semester

of 2010 and included 35 courses. An extra midterm

evaluation was setup for all courses in the 6th week

of the semester. The midterm evaluations were

identical to the end-of-term evaluations. The end-of-

term evaluations were conducted as usual in the 13th

week of the semester. The criteria for choosing

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

304

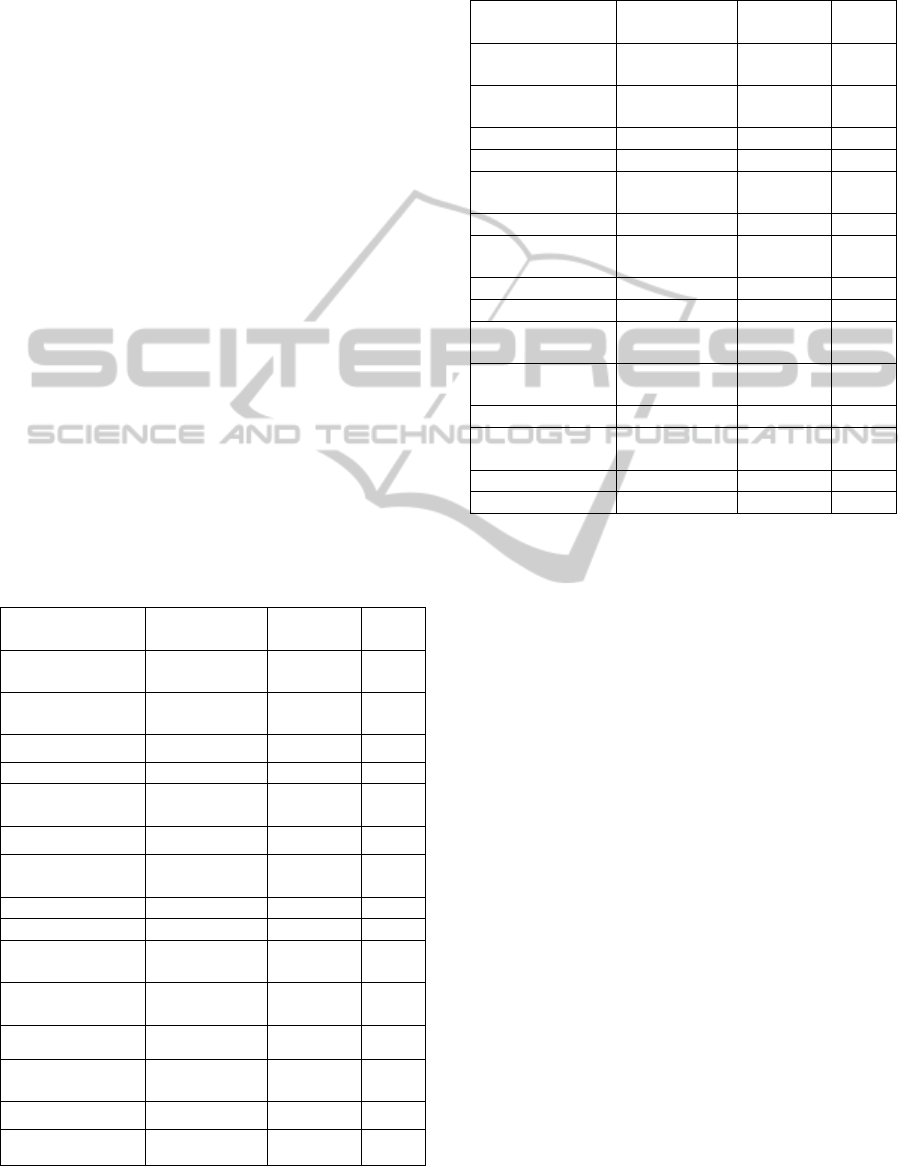

Table 1: The evaluation questions.

Id no. Question

Short version of

question (for

reference)

A.1.1

I think I am learning a lot in

this course

Learning a lot

A.1.2

I think the teaching method

encourages my active

participation

TM activates

A.1.3

I think the teaching material is

good

Material

A.1.4

I think that throughout the

course, the teacher has clearly

communicated to me where I

stand academically

Feedback

A.1.5

I think the teacher creates

good continuity between the

different teaching activities

TAs continuity

A.1.6

5 points is equivalent to 9

hours per week. I think my

performance during the course

is

Work load

A.1.7

I think the course description's

prerequisites are

Prerequisites

A.1.8

In general, I think this is a

good course

General

B.1.1

I think that the teacher gives

me a good grasp of the

academic content of the

course

Good grasp

B.1.2

I think the teacher is good at

communicating the subject

Communication

B.1.3

I think the teacher motivates

us to actively follow the class

Motivate

activity

B.2.1

I think that I generally

understand what I am to do in

our practical assignments/lab

courses/group

computation/group

work/project work

Instructions

B.2.2

I think the teacher is good at

helping me understand the

academic content

Understanding

B.2.3

I think the teacher gives me

useful feedback on my work

Feedback

B.3.1

I think the teacher's

communication skills in

English are good

English/English

skills

courses were that:

1. The expected number of students for the course

should be more than 50

2. There should be only one main teacher in the

course

3. The course should not be subject to other

teaching and learning interventions (which

often imply additional evaluations)

The courses were randomly split into two groups:

one half where the teacher had access to the results

of the midterm evaluations (both ratings and

qualitative answers to open questions) and another

half where that was not the case (the control group).

The courses were split such that equal proportions of

courses within each Department were assigned to the

two groups. The distribution of responses in the two

groups is given in Table 2. Furthermore the number

of students responding at the midterm and final

evaluations and the number of students who replied

both evaluations are listed. For each question the

number of observations can vary slightly caused by

students who neglected to respond to one or more

questions in a questionnaire.

The majority of the courses were introductory (at

Bachelor level), but also a few Master’s courses

were included. The courses were taken from six

different Departments: Chemistry, Mechanics,

Electronics, Mathematics, Physics, and Informatics.

Table 2: The two groups in the experiment.

Access to

midterm

evaluations

Number of

courses

No. of

matched

responses

Percentage o

f

responses

Yes 17 687

53

No 18 602

46.7

No further instructions were made to the teachers

on how to utilize the evaluations in their teachings.

3 METHOD

It has been disputed whether, and to what extent,

SET ratings are influenced by extraneous factors

(Marsh, 1987; Cohen, 1981). In the present study it

is taken into consideration that student evaluations

may be biased, e.g. by different individual reactions

to the level of grading or varying prior subject

interest (Wachtel, 1998; Richardson, 2005), or as a

result of systematic factors related to the course such

as class size or elective vs. compulsory (McKeachie,

1997; Wachtel, 1998; Alamoni, 1999). In order to

test the differences between midterm and final

evaluations as well as differences between

with/without access to midterm evaluations while

removing factors like students’ expected grade

(Wachtel, 1998; Clayson, 2009) or high/low rated

courses, we performed two kinds of tests.

a) Paired t-tests where a student from midterm to

the final evaluation is a paired observation and we

test the null-hypothesis that there is no difference

EffectsofMid-termStudentEvaluationsofTeachingasMeasuredbyEnd-of-TermEvaluations

-AnEmpericalStudyofCourseEvaluations

305

between midterm and final evaluations (Johnson et

al., 2011).

b) t-tests for the null-hypothesis that there is no

difference between having access to the midterm

evaluations and not (Johnson et al., 2011).

These tests were based on differences in evaluations

for the same student in the same course from

midterm to end-of-term evaluation in order to

remove course, teacher, and individual factors. In

Table the number of students who answered both

midterm and final evaluations are referred to as the

number of matches.

4 RESULTS

Pairwise t-tests were conducted for the null-

hypothesis that the mean of the midterm evaluations

were equal to the mean of the end-of-term

evaluations for each question related to either the

course or the course teacher. The results are

summarized in Table 3 and Table 4 for the courses

where the teacher had access to the midterm

evaluation results and those who had not,

respectively.

Table 3: Summary of pairwise t-tests between midterm

and end-of-term course and teacher evaluations. For

courses without access to the evaluations.

Final-midterm

Mean difference

(std)

p-value

p-value

< 0.05

A.1.1

(Learning a lot)

-0.056 (0.96) 0.17 No

A.1.2

(TM activates)

-0.053 (0.98) 0.21 No

A.1.3 (Material) -0.065 (1.0) 0.13 No

A.1.4 (Feedback) 0.081 (1.1) 0.085 No

A.1.5

(TAs continuity)

-0.075 (1.0) 0.095 No

A.1.6 (Work load) -0.040 (0.15) 0.53 No

A.1.7

(Prerequisites)

-0.049 (1.2) 0.32 No

A.1.8 (General) -0.12 (0.97) 0.0038 Yes

B.1.1 (Good grasp) -0.044 (0.86) 0.23 No

B.1.2

(Communication)

-0.066 (0.84) 0.068 No

B.1.3 (Motivate

activity)

-0.035 (0.90) 0.36 No

B.2.1 (Instructions) -0.048 (0.99) 0.33 No

B.2.2

(Understanding)

-0.012 (0.85) 0.78 No

B.2.3 (Feedback) -0.015 (0.97) 0.76 No

B.3.1 (English) -0.046 (0.79) 0.54 No

Table 4: Summary of pairwise t-tests between midterm

and end-of-term course and teacher evaluations. For

courses with access to the evaluations.

Final-midterm

Mean difference

(std)

p-value

p-value

< 0.05

A.1.1 (Learning a

lot)

0.089 (0.77) 0.0040 Yes

A.1.2 (TM

activates)

0.048 (0.93) 0.20 No

A.1.3 (Material) 0.019 (0.88) 0.59 No

A.1.4 (Feedback) 0.18 (1.0) <0.0001 Yes

A.1.5 (TAs

continuity)

0.039 (0.92) 0.29 No

A.1.6 (Work load) 0.058 (1.4) 0.30 No

A.1.7

(Prerequisites)

0.053 (0.93) 0.16 No

A.1.8 (General) 0.039 (0.85) 0.26 No

B.1.1 (Good grasp) 0.020 (0.78) 0.50 No

B.1.2

(Communication)

0.039 (0.74) 0.15 No

B.1.3 (Motivate

activity)

0.016 (0.89) 0.64 No

B.2.1 (Instructions) -0.038 (0.94) 0.36 No

B.2.2

(Understanding)

0 (0.89) 1.0 No

B.2.3 (Feedback) 0.059 (1.0) 0.20 No

B.3.1 (English) -0.071 (0.73) 0.13 No

For the courses without access to the midterm

evaluations the general trend is that the evaluations

are better at midterm than at end-of-term. This is

seen as the mean value of the midterm evaluations

subtracted from the final evaluations are negative for

most questions. In contradiction, the courses with

access to the midterm evaluations have a trend

towards better evaluations at the end-of-term, i.e. the

means of the differences are positive. The question

related to the general satisfaction of the course

(A.1.8) got significantly lower evaluations at end-of-

term when the teacher did not have access to the

midterm evaluations (p = 0.0038). The question

related to the academic feedback throughout the

course (A.1.4) got significantly higher scores at the

end-of-term when the teacher had access to the

midterm evaluations (p < 0.0001). The question

related to whether the student felt he/she learned a

lot (A.1.1) got significantly higher evaluations at

end-of-term when the teacher had access to the

midterm evaluations (p = 0.0040). The increase or

decrease in student evaluations were of average

values in the range [-0.12,0.18]), and significant

changes were of average absolute values [0.089;

0.18], (A.1.1 with access being the lowest and A.1.4

with access being the highest). The size of the

(dis)improvement should be compared with the

standard deviations of the differences divided by the

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

306

squareroot of two (approximately 0.7), which is the

standard deviation of the scores where the student

effect has been removed.

For the last analysis the midterm evaluations

were subtracted from the end-of-term evaluations for

each student and each course. The two groups

with/without access to midterm evaluations were

then compared based on these differences using a

two sample t-test for differences between means; the

results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5: Summary of t-tests of the null-hypothesis that

there is no difference in the evaluation differences from

midterm to end-of-term between courses with and without

access to the midterm evaluations. A folded F-test was

used to test if the variances of the two groups were equal.

If so, a pooled t-test was used, otherwise the

Satterthwaite’s test was used to check for equal means.

With-without access Mean

difference

p-value Significant

(p-value <

0.05)

A.1.1 (Learning a lot) 0.15 0.0045 Yes

A.1.2 (TM activates) 0.10 0.071 No

A.1.3 (Material) 0.084 0.13 No

A.1.4 (Feedback) 0.099 0.11 No

A.1.5 (TAs continuity) 0.11 0.05 Yes

A.1.6 (Work load) 0.098 0.24 No

A.1.7 (Prerequisites) -0.0037 0.95 No

A.1.8 (General) 0.16 0.0032 Yes

B.1.1 (Good grasp) 0.064 0.18 No

B.1.2 (Communication) 0.11 0.021 Yes

B.1.3 (Motivate activity) 0.051 0.32 No

B.2.1 (Instructions) 0.0095 0.88 No

B.2.2 (Understanding) 0.012 0.84 No

B.2.3 (Feedback) 0.073 0.27 No

B.3.1 (English skills) -0.025 0.77 No

The general trend is that the courses where the

teacher had access to the midterm evaluation results

get a larger improvement in evaluations at the end-

of-term than those where the teachers did not have

that access (the differences are positive). The only

exceptions to this trend are found in two questions

regarding factors that cannot be changed during the

course (course description of prerequisites (A.1.7)

and teacher’s English skills (B.3.1)). However, these

are not significant. The questions related to the

student statements about learning a lot, the

continuity of the teaching activities, the general

satisfaction with the course, and the teacher’s ability

to communicate the subject (A.1.1, A.1.5, A.1.8, and

B.1.2) had significantly higher increases from

midterm to end-of-term when the teachers had

access to the midterm evaluations, compared to the

courses where the teachers did not have access. Note

that the significant differences in means for the

questions are of sizes in the range [0.11, 0.16].

According to subsequent interviews (made by

phone), the percentage of the courses with access to

the midterm evaluations where the teachers say they

shared midterm evaluations with students was 53%,

and the percentage of courses where the teachers say

they made changes according to the midterm

evaluations was 53%. The percentage of the courses

with access to the midterm evaluations where the

teachers say they either shared the evaluations, made

changes in the course, or both was 71%.

5 DISCUSSION

The results illustrate that students are generally more

satisfied with their courses and teachers at end-of-

term when midterm evaluations are performed

during the course and teachers are informed about

the results of the evaluations.

According to the evaluations, students perceive

that courses improve when midterm evaluations are

performed and the evaluations and the teachers are

informed. Though the teachers were not instructed

how to react on the results from the mid-term

evaluation, it turned out that almost ¾ of the

teachers followed up on the evaluations by sharing

the results with their students and/or making changes

in the course for the remaining part of the semester.

The fact that ¼ of the teachers acted like the group

who were not allowed access to the midterm results

could cause the effects to be even smaller than if all

teachers acted. The effects are relatively large when

compared to the standard deviation of the scores

where the student effect has been removed:

approximately 0.7.

We expect that the actions upon the midterm

evaluations of the ¾ in many cases have included

elaborated student feedback to the teacher, a

dialogue about possible improvements, and various

interventions in the ongoing teaching and learning

activities, which can explain the increased

satisfaction as expressed in the end-of-term

evaluation. For this to happen, the teachers should

both be motivated and able to make relevant

adjustments (Yao and Grady, 2005). The ability to

make relevant adjustments will usually increase as a

result of participation in teacher training programs

that will also encourage teachers to involve both

students and peers in teaching development

activities. However, less than half of the teachers

responsible for the courses in this study have

participated in formal University teacher training

programs. The proportion of the teachers who have

EffectsofMid-termStudentEvaluationsofTeachingasMeasuredbyEnd-of-TermEvaluations

-AnEmpericalStudyofCourseEvaluations

307

participated in training programs is the same for

both groups of courses (35 % and 38 %,

respectively). Therefore, the observed effect of the

mid-term evaluation does not seem to be directly

dependent of whether the teacher has participated in

formal teacher training.

For future work it would be of interest to directly

measure the placebo effect of conducting midterm

evaluations as opposed to also measuring the effect

of real improvement.

From the student comments in the evaluation

forms we noticed that there in some courses was a

development pointed out. As an example one student

writes at midterm that: “A has a bad attitude;

Talking down to you when assisting in group work”.

At end-of-term the student writes: “In the beginning

of the course A’s attitude was bad – but here in the

end I can’t put a finger on it”. Such a development

was found in courses with access to the midterm

evaluations and where the instructor said he/she

made changes according to the evaluations. This

illustrates the usefulness of midterm evaluations

when addressing students evaluations within a

semester.

In most of the courses the major points of praise

and criticism made by the students are reflected both

at midterm and end-of-term. Examples are: That the

course book is poor, the teaching assistants don’t

speak Danish, the lecturer is good etc. Thus such

points which are easily changed from semester to

semester rather than within a semester are raised

both from midterm and end-of-term evaluations.

Various studies show that mid-term evaluations

may change the attitudes of students towards the

teaching and learning process, and their

communication with the teacher, especially if the

students are involved actively in the process e.g. as

consultants for the teachers (Cook-Sather, 2009,

Fisher and Miller, 2008; Aultman, 2006; Keutzer,

1993) – and it may even affect the students’

subsequent study approaches and achievements

(Greenwald and Gilmore, 1997, Richardson 2005).

Such effects may also contribute to the improved

end-of-term rating in the cases where teachers with

access to the mid-term evaluation results share them

with their students.

There is evidence that SETs in general do not

lead to improved teaching as perceived by the

students (Marsh, 1987) and one specific study

quoted by Wachtel (1998) of faculty reactions to

mandatory SETs indicate that only a minority of the

teachers report making changes based on the

evaluation results.

However, the present study indicates that mid-

term evaluations (as opposed to end-of-term

evaluations) may provide a valuable basis for

adjustments of the teaching and learning in the

course being evaluated.

As the course teachers were not obliged to take

specific actions based on the mid-term evaluations,

the study gives a good illustration of how the

university policies can influence the courses by

deciding when to perform student evaluations.

It seems to be preferable to conduct midterm

evaluations if one is concerned with an improvement

of the courses over a semester (as measured by

student evaluations).

One may argue that both a midterm and an end-

of-term evaluation should be conducted. However, it

is a general experience that response rates decrease

when students are asked to fill in questionnaires

more frequently. If this is a concern, it could - based

on the results of this study - be suggested to use a

midterm evaluation to facilitate improved courses

and student satisfaction.

On the other hand, it is widely appreciated that

the assessment of students’ learning outcome should

be aligned with the intended learning outcomes and

teaching activities (TLAs) of a course in order to

obtain constructive alignment (Biggs and Tang,

2007). Therefore, to obtain student feedback on the

entire teaching and learning process, including the

alignment of assessment with objectives and TLAs,

an end-of-term student evaluation should be

performed after the final exams where all assessment

tasks have been conducted (Edström, 2008). In this

case, teachers can make interventions according to

the feedback only for next semester’s course. This

approach does not facilitate an improvement in

courses according to the specific students taking the

course a given semester.

Based on the results of the present study it could

be suggested to introduce a general midterm

evaluation as a standard questionnaire that focuses

on the formative aspect, i.e. with a limited number

of questions concerning issues related to the

teaching and learning process that can be changed

during the semester. It should conform to the

existing practice of end-of-term evaluations by

including open questions and making it possible for

the teacher to add questions – e.g. inviting the

students to note questions about the course content

that can immediately be addressed in the teaching.

This can serve as a catalyst for improved

communication between students and teacher

(Aultman, 2006).

As a consequence, the standard end-of-term

questionnaire could be reduced and focus on general

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

308

questions (like A.1.4, A.1.8. and B.1.1, see Table 1)

and matters that are left out in the mid-term

evaluation (e.g. teachers proficiency in English,

B.3.1). Besides, it could be considered to encourage

the teachers to use different kinds of consultations

by faculty developers and/or peers to interpret the

student feedback (ratings and comments) and

discuss relevant measures to take (Penny and Coe,

2004).

The present study considered improvements over

one semester as measured by end-of-term student

evaluations as opposed to long-term improvements

as well as studies including interviews with

instructors and students. These limitations were

discussed in more detail in the introduction of this

paper.

6 CONCLUSIONS

An empirical study conducting midterm as well as

end-of-term student evaluations in 35 courses at the

Technical University of Denmark was carried out in

the fall of 2010. In half of the courses the teachers

were allowed access to the midterm evaluations, and

the other half (the control group) was not. The

general trend observed was that courses where

teachers had access to the midterm evaluations got

improved evaluations at end-of-term compared to

the midterm evaluations, whereas the control group

decreased in ratings. In particular, questions related

to the student feeling that he/she learned a lot, a

general satisfaction with the course, a good

continuity of the teaching activities, and the teacher

being good at communicating the subject show

statistically significant differences in changes of

evaluations from midterm to end-of-semester

between the two groups. The changes are of a size

0.1-0.2 which is relatively large compared to the

standard deviation of the scores where the student

effect is removed of approximately 0.7.

If university leaders are to choose university- or

department-wise evaluation strategies, it is worth

considering midterm evaluations to facilitate

improvements of ongoing courses as measured by

student ratings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all the teachers and

students who participated in the study, the Dean of

Undergraduate Studies and Student Affairs Martin

Vigild for supporting the project, and LearningLab

DTU for assistance in carrying out the study.

Furthermore, the authors thank five anonymous

reviewers for their valuable comments.

REFERENCES

L. M. Alamoni, 1999. Student Rating Myths Versus

Research Facts from 1924 to 1998: Journal of

Personnel Evaluation in Education, 13(2): 153-166.

Vibeke Normann Andersen, Peter Dahler-Larsen &

Carsten Strømbæk Pedersen, 2009. Quality assurance

and evaluation in Denmark, Journal of Education

Policy, 24(2): 135-147.

L. P. Aultman, 2006. An Unexpected Benefit of Formative

Student Evaluations: College Teaching, 54(3): 251.

J. Biggs and C. Tang, 2007. Teaching for Quality

Learning at University, McGraw-Hill Education, 3

rd

Ed.

D. E. Clayson, 2009. Student Evaluations of Teaching:

Are They Related to What Students Learn? A Meta-

Analysis and Review of the Literature: Journal of

Marketing Education, 31(1): 16-30.

P. A. Cohen, 1980. Effectiveness of Student-Rating

Feedback for Improving College Instruction: A Meta-

Analysis of Findings: Research in Higher Education,

13(4): 321-341.

P. A. Cohen, 1981. Student rating of instruction and

student achievement. Review of Educational Research,

51(3): 281–309.

A. Cook-Sather, 2009. From traditional accountability to

shared responsibility: the benefits and challenges of

student consultants gathering midcourse feedback in

college classrooms, Assessment & Evaluation in

Higher Education, 34(2): 231-241.

K. Edström, 2008. Doing course evaluation as if learning

matters most: Higher Education Research &

Development, 27(2): pp. 95–106.

R. Fisher and D. Miller, 2008. Responding to student

expectations: a partnership approach to course

evaluation: Assessment & Evaluation in Higher

Education, 33(2): 191–202.

A. G: Greenwald and G. M. Gillmore, 1997. Grading

leniency is a removable contaminent of student

ratings, The American Psychologist, 52(11): 1209-16.

R. Johnson, J. Freund and I. Miller, 2011. Miller and

Freund’s Probability and Statistics for Engineers,

Pearson Education, 8

th

Ed.

D. Kember, D. Y. P. Leung and K.P. Kwan, 2002. Does

the use of student feedback questionnaires improve the

overall quality of teaching? Assessment and

Evaluation in Higher Education, 27: 411–425.

C. S. Keutzer, 1993. Midterm evaluation of teaching

provides helpful feedback to instructors, Teaching of

psychology, 20(4): 238-240.

R. Likert, 1932. A Technique for the Measurement of

Attitudes, Archives of Psychology 140: 1–55.

EffectsofMid-termStudentEvaluationsofTeachingasMeasuredbyEnd-of-TermEvaluations

-AnEmpericalStudyofCourseEvaluations

309

H. W. Marsh, 1987. Students’ evaluations of university

teaching: research findings, methodological issues,

and directions for future research: International

Journal of Educational Research, 11: 253–388.

H.W. Marsh and D. Hocevar, 1991. Students’ evaluations

of teaching effectiveness: The stability of mean ratings

of the same teachers over a 13-year period, Teaching

and Teacher Education, 7: 303–314.

H. W. Marsh and L. Roche, 1993. The Use of Students’

Evaluations and an Individually Structured

Intervention to Enhance University Teaching

Effectiveness, American Educational Research

Journal, 30: 217-251.

W. J. McKeachie, 1997. Student ratings: The Validity of

Use, The American Psychologist, Vol. 52(11): 1218-

1225.

R. L. Oliver and E. P. Sautter, 2005. Using Course

Management Systems to Enhance the Value of Student

Evaluations of Teaching, Journal of Education for

Business, 80(4): 231-234.

A. R. Penny and R. Coe, 2004. Effectiveness of

consultation on student ratings feedback: A meta-

analysis.: Review of educational Research, 74 (2):

215-253.

J. T. E. Richardson, 2005. Instruments for obtaining

student feedback: A review of the literature. Asessment

and Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(4): 387–

415.The Technical University of Denmark, web sites

http://www.kurser.dtu.dk/finalevaluationresults/Defaul

t.aspx?language=da-DK

http://www.learninglab.dtu.dk/English/kurser/undervis

ere/udtu.aspx

H. Wachtel, 1998. Student Evaluation of College Teaching

Effectiveness: a Brief Overview. Assessment and

Evaluation in Higher Education, 23(2): 191–213.

Y. Yao, Y. and M. Grady, 2005. How Do Faculty Make

Formative Use of Student Evaluation Feedback?: A

Multiple Case Study. Journal of Personnel Evaluation

in Education, 18: 107–126.

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

310