Towards Evidence-aware Learning Design for the Integration of

ePortfolios in Distributed Learning Environments

Ang

´

elica Lozano-

´

Alvarez, Juan I. Asensio-P

´

erez and Guillermo Vega-Gorgojo

GSIC-EMIC, University of Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain

Keywords:

ePortfolio, Design Model, Learning Design, Distributed Learning Environment, Computer Supported

Collaborative Learning.

Abstract:

The benefits of using ePortfolios in widespread Distributed Learning Environments are hindered by two prob-

lems: students have difficulties in selecting which learning artifacts may demonstrate the acquisition of certain

learning skills; and, both teachers and students have difficulties in collecting evidences produced by means

of distributed and heterogeneous tools. This paper proposes a model aimed at enhancing the description of

learning activities with information about the evidences they are expected to generate. This model is a first

step towards the definition of an evidence-aware learning design process by means of which teachers make

explicit pedagogical-informed decisions involving the generation and subsequent utilization of learning evi-

dences. As a proof of concept, we apply this model in an authentic learning scenario, trying to alleviate the

two aforementioned problems.

1 INTRODUCTION

Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) is a research

field that promotes the use of information technolo-

gies to better support learning. Following this ap-

proach, it is common to use VLEs (Virtual Learning

Environments) (Dillenbourg, 2000) to orchestrate the

involved activities by managing students and groups

of them, as well as learning tools and resources. In

addition to VLEs, teachers typically make use of ex-

ternal tools, specially Web 2.0 ones such as blogs or

wikis, in their learning settings. Indeed, there are a

number of approaches to integrate third-party tools in

VLEs such as IMS LTI (IMS-LTI, 2012) or GLUE!

(Alario-Hoyos et al., 2013). As a result, the term

DLE (Distributed Learning Environment) (MacNeill

and Kraan, 2010) is employed to refer to the techno-

logical setting composed of VLEs and external tools.

On the other hand, ePortfolios, may be understood

as an organized compilation of selected work sam-

ples (evidences), which show the process and results

of a learning path (Barber

`

a-Gregori and Mart

´

ın-Rojo,

2009). ePortfolios are gaining momentum, due to

their benefits over the cognitive process of the stu-

dents (Barrett, 2007b) (Buzzetto-More, 2010) (Reese

and Levy, 2009).

By using ePortfolios, learners get a better under-

standing of their own learning progress and their level

of accomplishment of the targeted competences, as

well as increase their motivation for learning (Sweat-

guy and Buzzetto-More, 2007). At the same time,

teachers may complement traditional summative eval-

uation with formative assessment and feedback on the

on-going work, considering ePortfolios as both a pro-

cess and a product (Barrett, 2011).

However, when putting together ePortfolios and

technically heterogeneous DLEs, the assessment of

individual students becomes specially difficult, due

to learning evidence dispersion among the employed

tools (Buba

ˇ

s et al., 2011) (Barrett, 2007a). Teach-

ers’ workload increases when trying to gather those

work samples. At the same time, students find it dif-

ficult to understand and choose the suitable pieces of

work which allow showcasing the acquired compe-

tences (Buzzetto-More, 2010). These problems are

exacerbated in group work due to the complexity of

collaboration (Koschmann, 1996).

Hence, teachers should be helped to gather ev-

idences, plan and carry out assessment; while stu-

dents should be guided to exploit the advantages of

ePortfolios in these environments (Barber

`

a-Gregori,

2005). In order to reach this purpose, learning ev-

idences need to be identified among all the artifacts

generated by students in a learning situation. Also,

learning evidences need to be linked to learning ob-

jectives, as to clearly state which work samples help

405

Lozano-Álvarez A., I. Asensio-Pérez J. and Vega-Gorgojo G..

Towards Evidence-aware Learning Design for the Integration of ePortfolios in Distributed Learning Environments.

DOI: 10.5220/0004382804050410

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2013), pages 405-410

ISBN: 978-989-8565-53-2

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

reaching which goals.

This way, it seems important that teachers are

asked to make explicit the aforementioned guidelines.

Learning design (Conole, 2012) (Laurillard, 2012)

has evolved during the last decade as the approach

for helping educators to make their pedagogical de-

cisions, as well as the use of educational technology,

explicit and sharable. However, no attention has been

paid so far, within the learning design community,

to the inclusion of learning evidences (and their pur-

pose) in the design of learning situations. Therefore,

this paper proposes a so-called learning evidence-

aware model that defines how a teacher might define

learning evidences and how he might relate those ev-

idences with the components of current learning de-

signs.

This contribution is seen as a first, necessary step

to build a solution aimed at avoiding the main draw-

backs of integrating ePortfolios in DLEs. That is,

in order to be able to exploit technology for the au-

tomation of evidence collection (and, therefore, miti-

gate the workload increase due to ePortfolios), teach-

ers are required to explicitly identify those artifacts

which will be considered learning evidences and the

purposes and learning objectives they will serve to.

At the same time, the link between learning evidences

and objectives will be explicit, therefore helping stu-

dents to exploit ePortfolios to build their digital iden-

tity, by showcasing what they have learned.

The structure of the document goes as follows.

Section 2 explains the most important problems

which students and teachers need to face, when using

ePortfolios in DLEs. Section 3 presents a learning

evidence integration model, which will enable tack-

ling the aforementioned problems; and applies it to

a DLE-based learning situation. Finally, conclusions

and future work are given in Section 4.

2 ePortfolios AND DLEs

ePortfolios are known for their capability of docu-

menting the learning process, being an ordered store

of work samples, called learning evidences. In or-

der to do so, evidences must go through the following

processes: collection, selection, reflection and presen-

tation (Barber

`

a and Bautista, 2006).

That is, students need to take samples of their

work, decide whether they are suitable to show

the achievement of some learning objectives, self-

evaluate their work on the selected samples and fi-

nally publish the contents of their portfolio so that the

audience may understand how far they got in reaching

a given competence.

By doing so, ePortfolios help students to become

aware of their self-progress, increasing their under-

standing of what, why and how they learnt (Barrett,

2007b). This capability (providing a glance at the

learning path) also enables the use of ePortfolios as

assessment tools (Balaban et al., 2011).

Three main approaches may be followed in the use

of ePortfolios (Barrett, 2011). On a first approach,

ePortfolios may be seen as a way to centralize digi-

tal work samples. That is, the main purpose of this

kind of portfolios is storage, paying special attention

to evidence collection.

Secondly, the selection of evidences allows the use

of ePortofolios as a workspace, focused on the ongo-

ing learning situation. Students execute short-term re-

flection on the learning process, while teachers should

provide feedback and formative assessment towards

the aimed learning objectives.

Finally, students may present the level of achieve-

ment of certain competences by using the ePortfo-

lios as a showcase of their final retrospective on what

they learned, either after a given learning situation or

across several ones.

This way, in order to exploit those benefits in dis-

tributed learning environments, some proposals ap-

pear, for the joint use of VLEs, web 2.0 and ePortfo-

lio systems (Salinas et al., 2011) (Buba

ˇ

s et al., 2011)

(H

¨

am

¨

al

¨

ainen et al., 2011).

However, even when a conceptual link is estab-

lished among VLE, tools and ePortfolios, there is

not a real connection among them, thus hindering the

management of learning evidences. This means that,

at the end of the learning situation, the work sam-

ples are scattered along the different tools or the VLE

itself, difficulting their gathering and the teacher’s

tasks to provide assessment (either summative, for-

mative of feedback). This problem gets more com-

plicated in collaborative flows, including portfolios.

The teachers’ workload increases, while their confi-

dence in portfolio benefits decreases (Balaban et al.,

2011) (Sweat-guy and Buzzetto-More, 2007). Addi-

tionally, lack of consistency among different teachers

for the same learning objectives may appear (Barber

`

a-

Gregori, 2005).

From the students’ perspective, the main prob-

lem in evidence selection is their lack of experience

in doing so. It may be difficult for them to identify

which parts of their work better match the learning

objectives (Barrett, 2007b) (Barber

`

a-Gregori, 2005)

(Buzzetto-More, 2010).

Taking all this into account, it seems reasonable

for teachers to devote some time to decide which

learning evidences are most interesting to fit the learn-

ing objectives they aim at. That is, they should be

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

406

able to explicitly identify what to collect, what for and

how that links to the learning objectives they defined

(Venn, 2004).

This kind of decisions should be taken when de-

signing the learning situation. At that point, the flow

of activities to be executed is specified, where stu-

dents and teachers play roles and use services and

tools with the aim of accomplishing their learning

goals (Conole, 2012) (Laurillard, 2012). Some re-

search works criticize that current Learning Design

(LD) approaches do not allow the specification of data

flow among tools and activities (Palomino-Ram

´

ırez

et al., 2007) (Prieto et al., 2011). To address this limi-

tation, they propose workflow models for automating

the flow of learning artifacts in a learning situation.

However, their focus is mainly technological, leaving

out assessment considerations, as well as the use of

those artifacts for showcasing learning competences.

This paper, on the other hand, tries to go a lit-

tle further, by providing meaning to those artifacts,

highlighting the most relevant ones, and linking them

to the learning goals. Gathering all this information

in a structured manner is the first step towards au-

tomation of collection and management of learning

evidences. This way, technology can help to reduce

teacher workload in DLEs and to create better de-

signs, as well as to tackle students’ lack of experience

in evidence selection.

3 LEARNING EVIDENCE AWARE

DESIGN

Along the previous sections, the main difficulties in

the adoption of ePortfolios in DLEs have been spot-

ted.

The need of teachers taking learning evidences

into account in the design phase is identified as a nec-

essary step to provide technical aid to overcome those

difficulties. In order to do so, LD authoring tools,

such as Collage (Hern

´

andez-Leo, 2006) (Villasclaras-

Fern

´

andez et al., 2009), may be used. Design tools

offer certain possibilities to describe a learning sit-

uation, by using the model they implement as ref-

erence. However, none of those models explicitly

talk about learning evidences, nor ePortfolios (Prieto

et al., 2011) (Palomino-Ram

´

ırez et al., 2008).

Therefore, Section 3.1 proposes a design model

to integrate learning evidences in the design of learn-

ing situations, while Section 3.2 instantiates a CSCL

situation in which learning evidences play an impor-

tant role. By doing so, the basis of an evidence-aware

design process is set, which will allow overcoming

the main problems in the integration of ePortfolios

in DLEs. The aim of this process is to help teach-

ers elaborate an evidence-aware design, by applying

the proposed model.

3.1 Learning Evidence Integration

Model

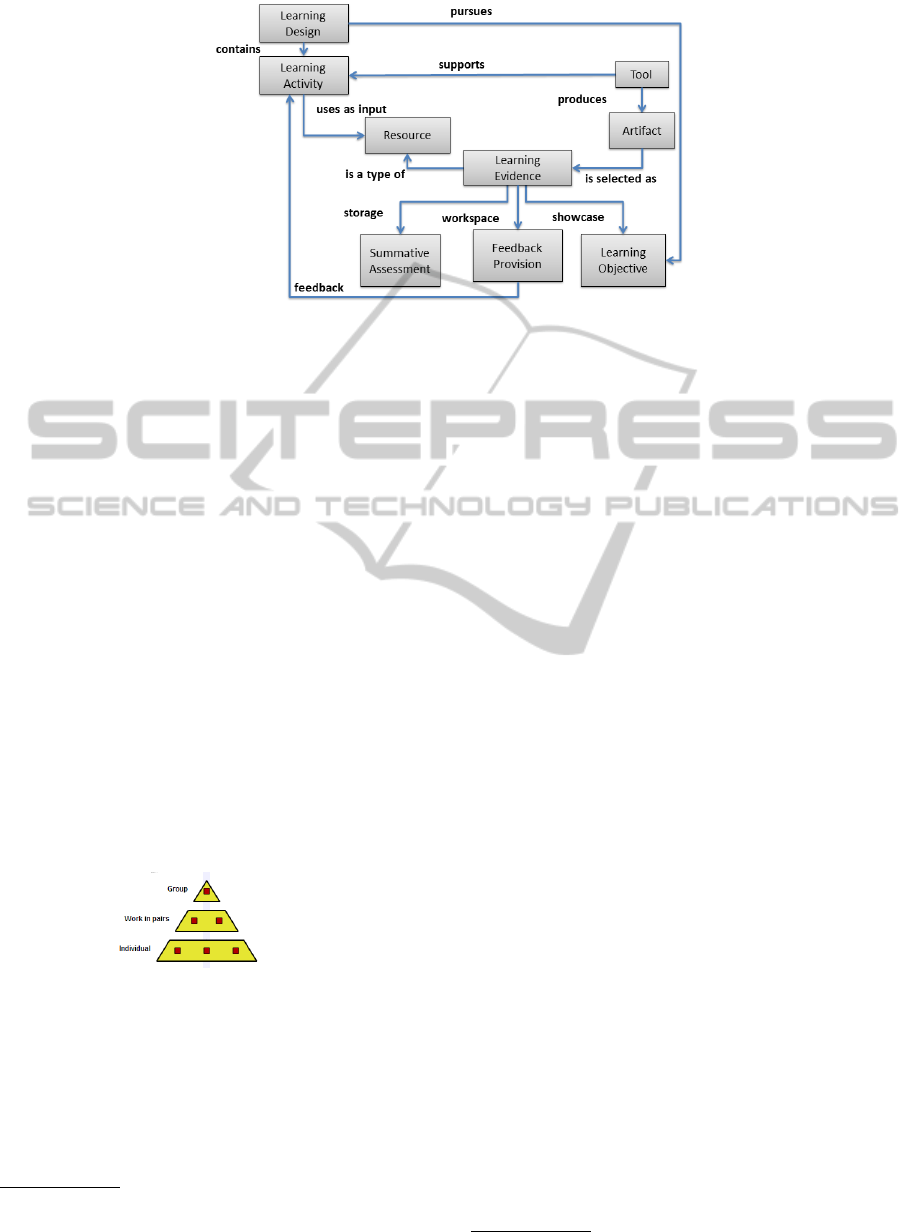

Figure 1 depicts the proposed integration model to in-

clude learning evidences in the design of learning sit-

uations.

Learning objectives are inherently linked to the

learning design itself, which will contain some

learning activities, leading to those goals. Learning

activities are supported by different tools (either in-

side or out of the VLE), which produce work samples

to evidence the student’s progress.

There are several purposes an evidence may pur-

sue (as detailed in Section 2). First, simple storage

will allow later use and summative assessment. For

example, the mind map at the end of a given activ-

ity may be evaluated by the teacher when the learning

situation is over.

However, learning evidences may be also used

along the enactment of the learning situation, in order

to provide feedback on the student’s learning path,

either by the teacher or the students themselves.

Finally, it is important to indicate which learning

evidences demonstrate which learning objectives, so

that students may use this information to showcase

the acquired competences.

By specifying all this information, a cyclic work-

flow is established. Learning evidences are the output

product of given steps in the learning process, but may

also become input resources in forthcoming learning

and/or assessment activities; as shown in the example

in Section 3.2.

3.2 Application Scenario

This section applies the evidence-aware learning de-

sign model described in Section 3 to a collabora-

tive scenario, inspired in a course in the study plan

for Telecommunications Engineering at the Univer-

sity of Valladolid (Networks and Telematics Systems,

3rd semester

1

). This course, among other topics, cov-

ers the analysis of network diagrams, and the use of

network discovery and routing tools.

One of the learning situations in that course has

the following learning objectives:

• LO01: Depict and read network diagrams.

1

http://www.tel.uva.es/docencia/asignaturas/

descripcion.htm?controlador(titulacion)=Pcomun

&controlador(asignatura)=A45016

TowardsEvidence-awareLearningDesignfortheIntegrationofePortfoliosinDistributedLearningEnvironments

407

Figure 1: Learning Evidence Integration Model.

• LO02: Learn how to use network routing and di-

agnosis tools

• LO03: Understand that other’s work is important

to reach my objectives (positive interdependence)

• LO04: Learn how to use collaborative editing

tools

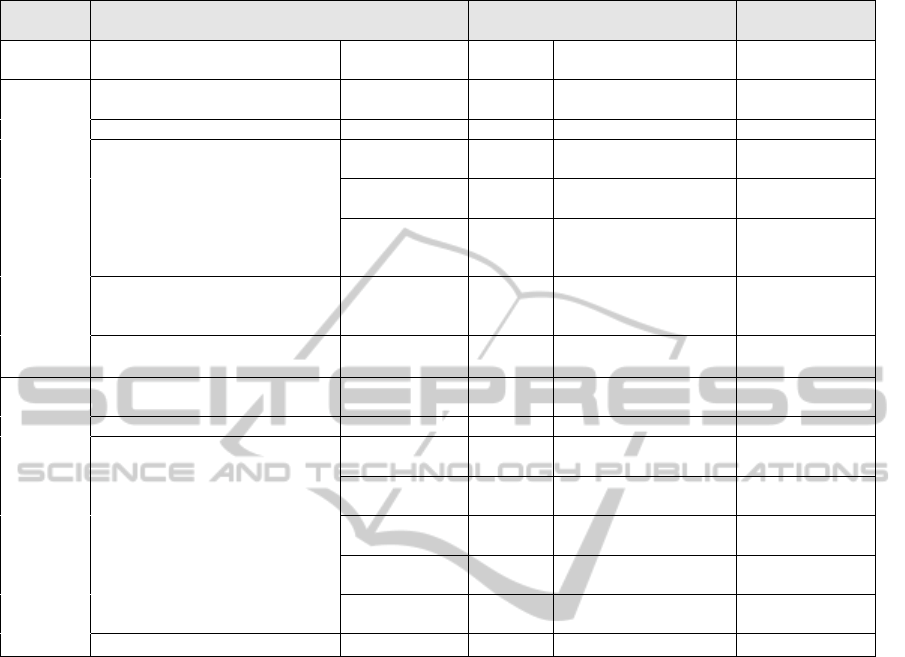

Focusing on those aims, the teacher decides to use

the pyramid collaborative pattern depicted in Figure 2

(Hern

´

andez-Leo, 2006). The leading thread along the

learning situation will be held by the VLE Moodle

2

,

but different activities will make use of specific tools:

Network Notepad

3

, Google Docs

4

.

Additionally, the teacher decides to exploit the

main capabilities of ePortfolios, by setting up an in-

stance of Mahara to be used as evidence meeting

point, so that teachers and peers may provide feed-

back over the generated artifacts. At the same time,

work samples may be shared across phases and stu-

dents.

A schema of this learning situation is depicted in

Table 1

Figure 2: High-level overview of the learning situation.

Being an example of DLE, generated artifacts are

scattered among tools, services and platforms. Count-

ing all evidences (networks diagrams, test results and

reports), the number of relevant artifacts goes up to

almost two and a half times the number of students.

That is, in a classroom of 40 people, the teacher ends

up facing 90 artifacts.

2

http://moodle.org/

3

http://www.networknotepad.com/

4

http://docs.google.com/

Both teacher assessment and peer review imply an

extra piece of work for authors of the artifacts, as they

need to manually gather their results and place them

in Mahara

5

. Also there is a lot of extra generated

items (drafts, execution logs...), needed to get to the

final product, whose link to learning objectives is not

clear to students.

By following the design model in Section 3.1,

as shown in Table 1, the teacher completes the tra-

ditionally provided information (activity description,

tool, ...), by explicitly picking up some artifacts (e.g.

[LE01]) to be considered as evidences. Those work

samples should go into the ePortfolio management

system (Mahara in the example), easing feedback pro-

vision and avoiding evidence dispersion.

Also, evidences may be identified as the output of

an activity, but also as input resources to some learn-

ing and/or assessment activities (e.g. [LE02]). These

pieces of information will be eventually used to in-

dicate an automation engine where to find and where

to place the necessary learning evidences to enact the

provided design.

Finally, evidences are clearly related to learning

objectives, which will help students understand what,

how and why they learnt.

To sum up, using the evidence-aware learning

model as reference is the first step to build a consis-

tent solution for the integration of ePortfolios in DLE.

Next lines of work are identified in Section 4.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Along this document, the challenges of using ePort-

folios in DLEs have been identified. First, students

lack of experience in evidence selection, which hin-

ders the task of linking work samples to learning ob-

5

http://mahara.org/

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

408

Table 1: Evidence-aware design of a pyramid (Learning Evidences in bold font).

Phase Learning Activity Tool Resource Artifact Learning

Objective

Individual Depict first draft of the ETSIT

Network, theoretical base

Network

Notepad

- Network Diagram

[LE01]

[LO01]

Work in

pairs

Review the first network draft by

my colleague

Mahara [LE01] Feedback [FB01] -

Consume feedback Mahara [FB01] - -

Depict second draft of the

ETSIT Network, empiric base

email - Collaboration mails

between students

-

ping, tracert,

lookup, whois

- Execution logs -

Network

Notepad

- Network diagram

[LE02]

[LO01],

[LO02],

[LO03]

Answer test Google Form - Questionnaire

Response

[LE03]

-

Teacher

Assess questionnaire re-

sponse

Google Form [LE03] - -

Groups Review the network diagram

generated by my colleagues

Mahara [LE02] Feedback [FB02] -

Consume feedback Mahara [FB02] - -

Create report, include network

diagram, support decisions on

theory

email - Collaboration mails

between students

-

chat - Collaboration conver-

sations among students

-

ping, tracert,

lookup, whois

- Execution logs -

Network

Notepad

- Network diagram -

Google Docs - Written report

[LE04]

[LO01],[LO02],

[LO03],[LO04]

Teacher

Assess written report Google Docs [LE04] - -

jectives. On the other hand, assessment of students

becomes harder when using ePortfolios in distributed

and heterogeneous environments, due to learning ev-

idence dispersion. Teachers are exposed to a larger

workload which decreases confidence in the benefits

of ePortfolios as assessment tools.

This paper supports the idea of making pedagogi-

cal decisions explicit on what evidences may be used

to prove the achievement of some learning objectives

and at which point within the learning situation they

must be taken. Teachers use learning design to untan-

gle their ideas to organize learning situations. How-

ever, current learning design approaches do not con-

sider the use of learning evidences. To overcome this

limitation, a model for the integration of learning ev-

idences has been presented in Section 3. This model

has been used on a sample scenario, to highlight the

use of evidences within a collaborative learning pat-

tern.

This way, by considering learning evidences in the

design phase, technology can be used to alleviate the

workload of teachers, as well as guide students to un-

derstand which work samples relate to which compe-

tences.

However, evidence collection remains a big prob-

lem in the chosen distributed and technically hetero-

geneous scenario, composed of VLE, external tools

and ePortfolio management systems. The develop-

ment of technical solutions for evidence gathering in

DLEs based on this model is the following step in this

research work. Additionally, the definition of a learn-

ing design process also based on the proposed model

is aimed, so as to influence teacher-oriented authoring

tools presented along this paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research has been partially funded by the Eu-

ropean Commission Lifelong Learning Programme

projects 531262-LLP-1-2012-1-ES-KA3-KA3MP

and 526965-LLP-2012-1-GR-COMENIUS-CMP,

the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competi-

tiveness project TIN2011-28308-C03- 02, and the

Autonomous Government of Castilla and Le

´

on,

Spain, project VA293A11-2.

TowardsEvidence-awareLearningDesignfortheIntegrationofePortfoliosinDistributedLearningEnvironments

409

REFERENCES

Alario-Hoyos, C., Bote-Lorenzo, M. L., G

´

omez-S

´

anchez,

E., Asensio-P

´

erez, J. I., Vega-Gorgojo, G., and Ruiz-

Calleja, A. (2013). GLUE!: An architecture for the

integration of external tools in Virtual Learning Envi-

ronments. Computers & Education, 60(1):122–137.

Balaban, I., Mu, E., and Divjak, B. (2011). Critical Success

Factors for the implementation of the new generation

of electronic Portfolio systems. In Proceedings of the

ITI 2011 33rd International Conference on Informa-

tion Technology Interfaces (ITI), pages 251–256.

Barber

`

a, E. and Bautista, G. (2006). Electronic port-

folio: development of professional competences (in

spanish). Revista de universidad y sociedad del

conocimiento (RUSC), 3:55–66.

Barber

`

a-Gregori, E. (2005). Evaluation of complex comple-

tences: using portfolio (in spanish). La Revista Vene-

zolana de Educaci

´

on (Educere), 9(31).

Barber

`

a-Gregori, E. and Mart

´

ın-Rojo, E. (2009). ePortfolio:

learning to evaluate the learning process (in spanish).

Editorial UOC.

Barrett, H. (2007a). ePortfolios and Adult Learning. In Pro-

ceedings of NIACE (National Institute of Adult Con-

tinuing Education).

Barrett, H. (2007b). Researching Electronic Portfolios and

Learner Engagement: The REFLECT Initiative. Jour-

nal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 50:436–449.

Barrett, H. (2011). Balancing the Two Faces of E-

Portfolios. British Columbia Ministry of Education,

Innovations in Education, 3(1).

Buba

ˇ

s, G., Coric, A., and Orehovacki, T. (2011). The in-

tegration of students’ artifacts created with Web 2.0

tools into Moodle, blog, wiki, e-portfolio and Ning. In

MIPRO, Proceedings of the 34th International Con-

vention, pages 1084–1089.

Buzzetto-More, N. (2010). The E-Portfolio Paradigm: In-

forming, Educating, Assessing, and Managing With E-

Portfolios. Informing Science.

Conole, G. (2012). Designing for Learning in an Open

World. Springer.

Dillenbourg, P. (2000). Virtual Learning Environments. In

Learning in The New Millennium: Building New Edu-

cation Strategies for Schools. EUN Conference Work-

shop on Virtual Learning Environments.

H

¨

am

¨

al

¨

ainen, H., Ikonen, J., and Nokelainen, I. (2011). The

status of interoperability in e-portfolios: Case Ma-

hara. In 7th E-learning Conference, e-Learning’11

(E-Learning and the Knowledge Society), volume 11,

pages 64–69, Bucharest, Romania.

Hern

´

andez-Leo, D. (2006). COLLAGE, a collaborative

learning design editor based on patterns. Educational

Technology & Society, 9(1):58–71.

IMS-LTI (2012). IMS Learning Tools Interoperability:

Specification. Technical report, IMS Global Consor-

tium.

Koschmann, T. (1996). CSCL: theory and practice of an

emerging paradigm. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates,

Inc.

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a Design Science: Build-

ing Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technol-

ogy. Routledge.

MacNeill, S. and Kraan, W. (2010). Distributed learning en-

vironments: a briefing paper. Technical report, JISC

Center for Educational Technology and Interoperabil-

ity Standards (CETIS).

Palomino-Ram

´

ırez, Mart

´

ınez-Mon

´

es, A., Bote-Lorenzo,

M., Asensio-P

´

erez, J., and Dimitriadis, Y. (2007).

Data flow between tools: Towards a composition-

based solution for learning design. In Seventh

IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learn-

ing Technologies, number Icalt, pages 354–358.

Palomino-Ram

´

ırez, L., Bote-Lorenzo, M., Asensio-P

´

erez,

J., Dimitriadis, Y., and de la Fuente-Valent

´

ın, L.

(2008). The Data Flow Problem in Learning Design

: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 6th Interna-

tional Conference on Networked Learning, Halkidiki,

Greece, pages 285–292.

Prieto, L. P., Asensio-P

´

erez, J. I., Dimitriadis, Y., and Ed-

uardo, G. (2011). GLUE ! -PS : A multi-language

architecture and data model to deploy TEL designs to

multiple learning environments. In Proceedings of the

6th European Conference on Technology Enhanced

Learning, EC-TEL 2011, Palermo, Italy. Universidad

de Valladolid.

Reese, M. and Levy, R. (2009). Assessing the Future: e-

portfolio trends, uses and options in higher education.

Research Bulletin - EDUCASE, 2009(4).

Salinas, J., Mar

´

ın, V., and Escandell, C. (2011). A case of

institutional PLE: integration of VLE and e-portfolio

for students. Technical report, Universitat de les Illes

Balears.

Sweat-guy, R. and Buzzetto-More, N. (2007). A Compar-

ative Analysis of Common E-Portfolio Features and

Available Platforms. Informing Science: International

Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline, 1(4):327–

342.

Venn, J. (2004). Assessing students with especial needs.

Prentice Hall.

Villasclaras-Fern

´

andez, E., Hern

´

andez-Leo, D., Asensio-

P

´

erez, J., Dimitriadis, Y., and Mart

´

ınez-Mon

´

es, A.

(2009). Towards embedding assessment in CSCL

scripts through selection and assembly of learning

and assessment patterns. In Proceedings of the Pro-

ceedings of the 9th international conference on Com-

puter supported collaborative learning, pages 507–

511, Rhodes, Greece.

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

410