Contemporary e-Learning as Panacea for Large-scale Software

Training

John van der Baaren and Iwan Wopereis

Centre for Learning Sciences and Technologies, Open University of the Netherlands, Heerlen, The Netherlands

Keywords: e-Learning, Software Training, Instructional Design, Electronic Medical Records.

Abstract: Large organizations renew their core business software with some regularity, resulting in serious challenges

for in-company training officers. Especially when large numbers of employees need to be trained to use

updated software on short notice, traditional face-to-face training methods fall short. Contemporary e-

learning is regarded a solution for such short-term and large-scale training. This paper discusses the effect of

a didactically sound e-learning solution on learning to use a new version of an Electronic Medical Record

(EMR) software package. This solution not only features generally recognized e-learning characteristics like

any time, place, path, and pace, but also marks the element ‘just enough’ to emphasize that the e-learning

content only covers knowledge (concepts and procedures) necessary to perform the daily professional tasks.

Around 2000 healthcare workers of a mental healthcare institution were educated online to use a renewed

version of an EMR software package within two months. Results (i.e., time on task, test results, and

perceived effectiveness) indicate that contemporary online solutions can help large organizations to face

short-term and large-scale training problems.

1 INTRODUCTION

Organizations largely depend on business software,

especially when this type of software supports core

processes of an organization (Pinn-Carlisle, 1999). It

is not uncommon that software companies renovate

business software packages with some regularity.

These new versions of core business software are a

serious challenge for in-company training officers.

Especially when large numbers of employees need

to be trained to use updated software versions on

short notice, traditional face-to-face training

methods fall short. For instance, when 2100

employees need to be trained to use renewed

software and a classroom-based setting is the

customary option to train software skills, an institute

would probably have to organize a minimum of 140

training sessions to train the total workforce (i.e.,

when a training session includes a four-hour training

for 15 employees, directed by one trainer). If an

institution has the disposal over one fully equipped

training classroom (i.e., a room with at least 15

computers), this means it would take at least 70 days

to instruct all employees of the institute, weather

permitting it is possible to schedule two training

session each day. In addition, such a training set-up

entails large organizational costs, since 2100

employees should get half a paid day off and receive

travelling expenses to attend a training session. In

situations like this e-learning is often considered a

panacea for learning and instruction (Clark and

Mayer, 2011; DeRouin et al., 2005; Driscoll, 2012;

Jochems et al., 2004). Since learners can proceed

through an e-learning course at their own place and

pace, and at any time, organizational costs related to

aforementioned organizational issues can be

minimized. Moreover, contemporary e-learning

offers opportunities for flexible instruction that is

tailored to the requirements of learners (Clark and

Mayer, 2011; Shute and Towle, 2003; Stoyanov and

Kirschner, 2004). However, until recently for many

organizations e-learning has proved long in lead

time to produce, inflexible to amend and

prohibitively expensive. Furthermore, the

development and implementation of e-learning has

been exclusively reserved to information technology

experts, rather than educational specialists.

Fortunately, due to a technology shift, new and

relatively easy to use tools have become available

for educationalists and trainers to facilitate e-

learning development and implementation (Driscoll,

2012; Weller et al., 2005).

612

van der Baaren J. and Wopereis I..

Contemporary e-Learning as Panacea for Large-scale Software Training.

DOI: 10.5220/0004384606120618

In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2013), pages 612-618

ISBN: 978-989-8565-53-2

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

This paper describes a project that used user-friendly

tools to create didactically sound e-learning courses

for a variety of Electronic Medical Record (EMR)

software users of Mondriaan, a large Dutch

institution for mental healthcare. Around 2000

employees of Mondriaan had to be trained within

two months’ time to use an upgraded EMR software

package called Psygis Quarant. Since employees

needed to be trained on short notice and training

facilities (i.e., availability of classrooms and

trainers) were relatively scarce, it was decided to

look for an e-learning solution. In addition, the

intention to develop e-learning courses geared the

adoption of contemporary instructional design

guidelines for designing the courses. An example of

a state-of-the art principle for designing instruction

is the whole task approach as basis for creating

learning tasks (Merrill, 2002; Van Merriënboer and

Kirschner, 2013). According to Merrill (2002)

“learning is promoted when learners are engaged in

a task-centered instructional strategy. […]. A task-

centered instructional strategy is a form of direct

instruction but in the context of authentic, real-world

problems or tasks. […] The effect of this strategy is

enhanced when learners undertake a progression of

whole tasks.” The task-centered instructional

strategy and other effective design principles, like

the demonstration principle, the application

principle, and the activation principle were

employed to design the e-learning courses.

An important goal of the Mondriaan project was

to study the effect of the instruction (i.e., the e-

learning courses) on EMR skill learning. Therefore

we explored student behaviour within the e-learning

courses and analysed perceived effects of these

courses on EMR skill learning. Results of the study

were used to compare the e-learning approach to

skill learning with customary classroom and onsite

training methods.

The main research question of this exploratory

study is:

- Is a contemporary e-learning method for

software training effective and more efficient than a

customary classroom training method?

In order to answer this question we formulated

sub-questions (measurement between brackets):

- Do participants of the course perceive the

course as effective / useful? (perceived effectiveness

of so called superusers);

- What do participants of the course do in order

to complete the course? (registration of time on task

and testing results of all participants);

- Did the e-learning work? (identification of

problems superusers faced within a four-week

period after the introduction of Psygis Quarant).

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants

A total of 1973 employees of Mondriaan, a Dutch

mental healthcare institution based in the south of

the Netherlands, entered the e-learning courses.

Participants belonged to one of four groups: (a)

administrative staff (n=172; ADMIN), (b) nursing

staff (n=956; NURSE), (c)

psychotherapy/psychiatric staff (n=659; PSYCH),

and (d) occupational therapeutic staff (n=186;

THERA). For analysing perceived course

effectiveness, evaluations of so-called superusers

(n=100) were analysed. Superusers are

representatives of the aforementioned groups. They

function as contacts within departments and help

solve problems users of the EMR software have.

Further, they serve as intermediate between the

EMR software user and information technologists of

the Mondriaan institute. The superuser group

included 26 administrators, (ADMIN), 33 nurses

(NURSE), 32 psychotherapists/psychiatrists

(PSYCH), and 8 occupational therapists (THERA).

2.2 Materials

2.2.1 Courses

For each of the four groups of users an e-learning

course was designed. Each course consisted of two

modules and a test. The first module covered an

introduction to the EMR software and was the same

for all users. The second module aimed at

professional task learning and was different for the

four groups. Each of these modules included

between six and nine tasks. Instructional design

principles for complex learning were used to design

the learning tasks (cf. Van Merriënboer and

Kirschner, 2013). Authentic tasks formed the basis

for designing the learning tasks. Tasks were

scheduled from easy (more instructional support) to

difficult (less support). Table 1 shows an overview

of the tasks covered in the courses for the four

different groups.

For each task two or more exercises were

designed with increasing difficulty level. During the

first exercise learners were guided through the task.

Contemporarye-LearningasPanaceaforLarge-scaleSoftwareTraining

613

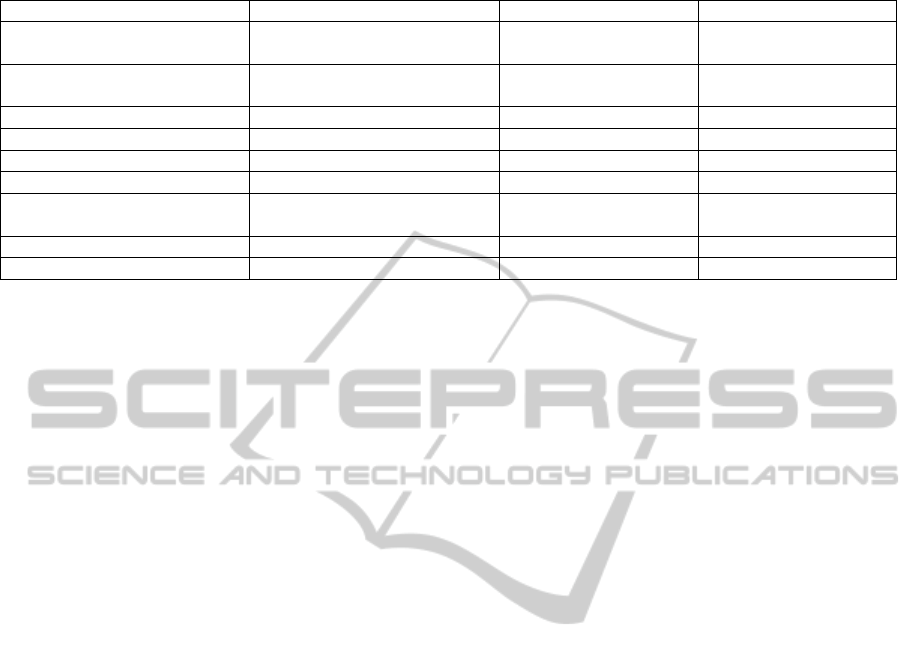

Table 1: Overview learning tasks per user group.

Course ADMIN Course THERA Course PSYCH Course NURSE

Registration and creating

dossier

Appointments and dossier (4)

Appointments and

dossier (4)

Report (6)

Unplanned activity (1)

Adapt appointment (5)

Adapt appointment (5)

Outside authorization

(2)

Outside authorization (2) Unplanned activity (1) Report (6) Consult archive (3)

Consult archive (3) Outside authorization (2) Consult archive (3) Guidance plan

Add documents Consult archive (3) Anamnesis Dialogue model plan

Make an appointment Report (6) Unplanned activity (1) Gordon model plan

Outgoing correspondence

Create sub plan

Outside authorization

(2)

Register client Day care plan Medication

Activity plan

Note: Numbers indicate the same task is used for different groups. Tasks without number are unique.

In subsequent excercises guidance was faded and

learner control had been increased. In the latter case

feedback was only given after wrong user actions.

Each exercise starts with a realistic task

description. An example of such a task description

is: “You just received the referral letter for Ms Post

born 06-10-1951. You are going to register her and

make an application for care for her. After that you

will create her dossier. Ms Post has not been in care

before.“ A task decription is followed by a ‘guided

interaction’ with the EMR application. To develop

the interactive exercises detailed scripts were

written. In total about 100 of these exercises were

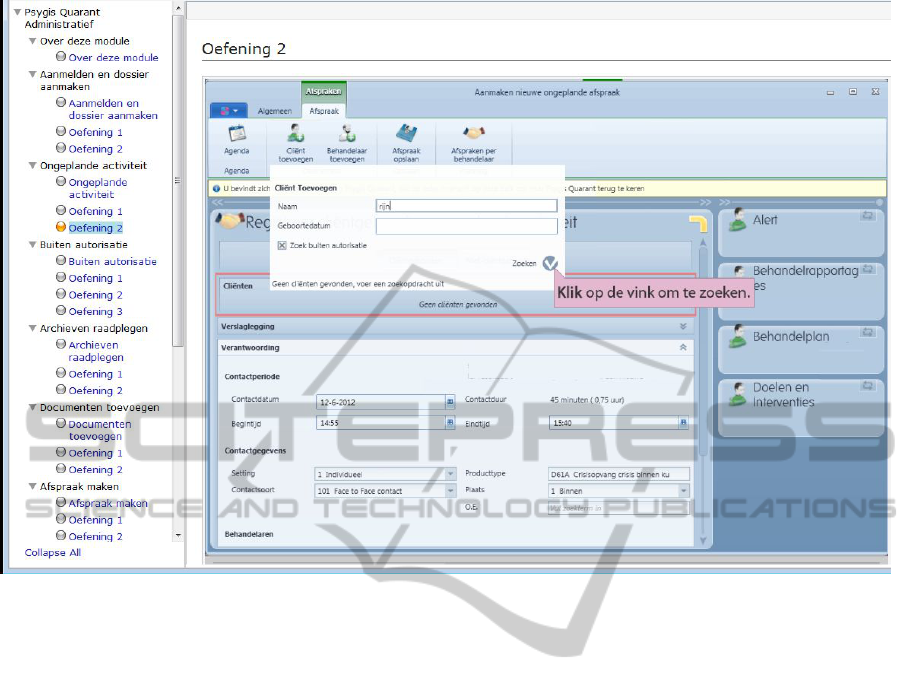

developed for the four courses. Figure 1 shows a

screenprint of an interactive exercise including

feedback.

Ilias V4.2.3 (www.ilias.de) was used as learning

management system. Ilias is an open source learning

system that also includes authoring facilities for

developing e-learning modules complying to the

SCORM standards and tests using a wide variety of

question types. Adobe Captivate 5.5 TM was used

for building the exercises. Ilias was linked to a

course/training management system called

Edumanager (www.lnm.nl). Based on the function

profile of the Mondriaan employee Edumanager

could ‘decide’ which of the four courses should be

offered. Ilias reported back to Edumanager when

somebody passed the test of the course.

2.2.2 Tests

For each course a test was constructed containing an

average of twelve multiple choice questions. Both

test items and test were made in Ilias V4.2.3. Test

items mainly focused on assessing (new) procedural

steps. Further, questions related to the updated

graphical user interface and questions aimed at

assessing conceptual understanding were added to

the test. Alternative answers of test items included

‘anticipated errors’, that is: possible errors identified

by Psygis Quarant experts.

The cut-of score for the test was set at 70%.

Because students were allowed to make the test

multiple times, alternative answers to questions were

randomized whenever possible. Ideally a question

pool would have been constructed but time and

resource constraints prohibited this. It was possible

to quit a test and continue it later on which was

practical because it could very well happen that a

test had to be interrupted for more urgent work.

2.2.3 Evaluation Form

The evaluation form consisted of 10 statements that

used a Likert-scale (1=completely disagree –

5=completely agree). Questions covered topics like

course login, the course modules (content, sequence,

readability), the test, and perceived effectiveness of

the e-learning course. Questions were selected from

the course evaluation database of the Open

University of the Netherlands (Westera et al., 2007).

Participants were able to add comments to each

question.

2.2.4 Follow-up Questionnaire

Four weeks after the launch of the new EMR

software a follow-up questionnaire was sent to the

superusers. The questionnaire consisted of 14

questions, both multiple-choice and open questions.

The questions covered problems encountered with

the e-learning courses (how many, nature of

problems), problems users encountered with the

EMR (how many, nature of problems), and the

evaluation of the e-learning tool. Questions were

selected from Westera et al. (2007).

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

614

Figure 1: Sample screenshot from the e-learning course showing an interactive exercise including feedback.

2.3 Procedure

A project team was formed consisting of e-learning

specialists from the Open University of the

Netherlands and ICT-support and training specialists

from the Mondriaan institute. A tight project plan

was needed because there was only a six-month

period between the start of the project and the start

of the training of the employees. The project

included phases for analysis, design, development,

testing the course with 100 users, and

implementation. The project was further

complicated by the fact that it was the first time the

electronic learning environment was used in the

organisation. Moreover the project was used to train

the Mondriaan project members to design and

maintain e-learning courses themselves.

The first step for the project members was to get

acquainted with the learning management system

(Ilias) and to select the necessary authoring tools. It

was decided to use the Ilias Scorm editor to build the

modules for the course and use Adobe Captivate 5.5

TM for building the exercises. To construct the tests

the Ilias test editor was used which supports a wide

variety of question types.

During the design phase of the project examples

were presented to a focus group for feedback. After

the development phase the 100 superusers tested

both the e-learning courses and the tests. Testing

was done during ten workshops in August 2012. The

superusers evaluated course and test content, time on

task, and time on test, and filled in an evaluation

form and a follow up questionnaire after four weeks.

The superusers also provided the project team with

valuable feedback and several errors could still be

corrected before the e-learning courses and tests

were finally implemented.

On 15 August 2012 all employees of Mondriaan

received an email asking them to follow the course

and complete the test before October 1st 2012. In the

two months before the launch employees were

already informed during plenary sessions and the

company website. The progress during this six week

period was closely monitored, reminders were

mailed and in some cases department heads were

informed that employees were lacking behind.

3 RESULTS

In order to answer the main research question of this

exploratory study, three sub-questions were posed.

In this section we will present the results necessary

to answer the sub-questions.

Contemporarye-LearningasPanaceaforLarge-scaleSoftwareTraining

615

3.1 Perceived Effectiveness

In order to measure perceived effectiveness, 100

superusers were asked to fill in a questionnaire after

the testing session (a two-hour workshop). Seventy-

two out of 100 returned the evaluation form. This

group was very positive about the e-learning. Sixty-

seven of 72 (93%) superusers indicated this form of

learning was well or very well suited for learning to

use an EMR. Also the specific course offered got

good marks:

- The structure of the course is logical: 98%

agreed or strongly agreed.

- Text was clear: 95% agreed or strongly agreed.

- Interactive exercises easy to understand: also

scored 95%.

Answers to the questions about the tests were also

positive, be it less outspoken:

- The questions were well formulated: 89%

agreed or strongly agreed.

- The questions were well connected to the course

content: 63% agreed or strongly agreed.

- Mastering the EMR software is tested well in

this way: 72% agreed or strongly agreed.

3.2 Course Progress

What did participants of the course do in order to

complete the course? Between 15 August and 1

October 2012, 1973 employees of Mondriaan

followed the e-learning course and completed the

test. During this six-week period, the e-learning ran

without any significant problems. A few people

complained they were offered the wrong course; this

was corrected manually. After six weeks almost

80% of all Mondriaan employees had successfully

completed the course. Table 2 presents the number

of employees that followed and completed the e-

learning courses and tests (successfully).

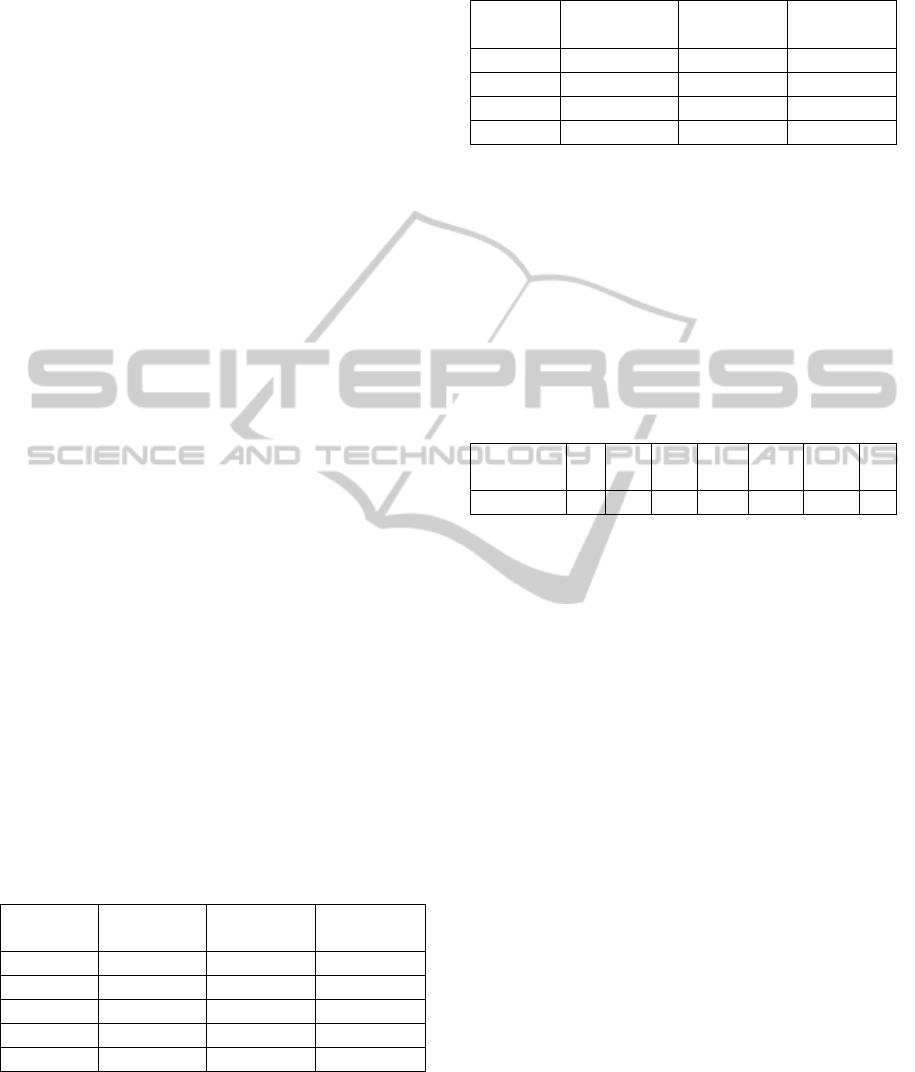

Table 2: Course completion rate.

No. users

No.

completed

%

completed

ADMIN 172 132 77

PSYCH 659 483 73

THERA 186 151 81

NURSE 956 749 78

Total 1973 1515 77

Note: reference date 3 October 2012.

Table 3 presents the time participants spent on

the course and the test. Overall it took the students

about one and a half hour to complete the course of

which about 20 minutes was spent on the test.

Table 3: Time on course, time on test and score test for

each function group.

Time

course

Time test Score test

ADMIN 1h46m 17m 88%

PSYCH 1h29m 15m 85%

THERA 1h41m 17m 84%

NURSE 1h22m 23m 80%

Note: reference date 3 October 2012

The average of one and a half hour for time on

course was well within the two hours that was

estimated for a classroom course on the topic.

The variation in study times suggests that the

freedom learners have compared to classroom

instruction is welcomed by many learners. Table 4

for instance shows a large variation in study times of

the administrators (ADMIN) course learners.

Table 4: Study times in minutes related to number of

learners that completed the ADMIN course.

Time

(minutes)

0-30

30-

60

60-

90

90-

120

120-

150

150-

180

>

Learners 15 12 28 33 11 11 26

3.3 Course Quality

Did the e-learning work? Four weeks after the

launch of the new EMR application an online

questionnaire was sent to the 100 superusers. After

one week 59 out of 100 had filled in the

questionnaire. The first two questions asked for

problems with the e-learning. The amount of

problems with the e-learning they received was

limited. 75% of them received 5 or less problems

during this period. Only a small amount of problems

were actually related to the content of the course.

Most problematic (19 times) was making the new

password needed to access the course. Second were

complaints about having the wrong course offered

(usually outdated or wrong information in the

personnel system). Several other problems were

mentioned some of which very useful in the context

of further development. But on a total of almost

2000 users the amount of problems was minimal

certainly taking into account this was the first time

e-learning was used. The question whether e-

learning was a good tool to use for this kind of

training was agreed with by 78% of the respondents.

Other questions looked into the problems users

had with using the new EMR application. In this

case more problems arose: 60% of the superusers

received 5 or less problems during this period. But

also in this case most problems were not related to

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

616

not being able to perform tasks but for instance to

wrong authorization leading to wrong clients in the

caseload. But some complaints clearly indicate

potential improvement in the design of the training.

For examples, several users complained some

actions did not work while they simply needed to

refresh the page they were working on. While this

information was provided in one of the course

modules it was clearly not practiced enough to be

remembered in the working context.

4 DISCUSSION

Large organizations regularly face new versions of

software applications. Especially when all

employees of an organization use a specific

application and both the old and new version of the

application cannot be supported concurrently, the

organisation is confronted with a major training

challenge. This study explored the effects of an e-

learning solution for large-scale software training

when large numbers of employees need to be trained

on short notice. Our research question was: Is a

contemporary (i.e., didactically and technologically

sound) e-learning method for software training

effective and more efficient than a customary

classroom training method?

A state-of-the art e-learning solution was

developed since the regular training approach (a two

hour classroom session for a maximum of 15

people) was not an option. The e-learning solution

was founded on contemporary instructional design

principles, like the whole task approach (cf. Van

Merriënboer and Kirschner, 2013). First, this study

explored the (perceived) effectiveness of the e-

learning solution in order to be able to conclude that

contemporary, didactically sound, e-learning courses

can be given preference to classroom training and

traditional e-learning solutions (i.e., the

‘computerized page-turners’; cf. Jochems et al.,

(2004)). Results of the questionnaires of the

superusers indicate that the e-learning courses and

tests were effective and a large majority of the

superusers stated that the courses are well suited for

learning to use (updated) EMR software.

Analyses of the time on task of participants who

finished their e-learning course showed that

participants managed to finish the course within an

hour and a half on average, which is less than the

expected two hours. In addition a high percentage of

the participants passed the concluding test, which

proved they gained the knowledge base necessary to

use the EMR software for daily professional tasks.

Also the effectiveness of the e-learning solution as

perceived by the group superusers turned out to be

positive. A total of 78% of the superusers concluded

that the e-learning courses were ideal for training an

upgraded version of the software.

The e-learning was designed using a “just

enough” principle and succeeded in training the

tasks users applied often in a time-efficient way.

Ideally the learning is continued on the job using

available online help facilities. However current

online help does not take a task perspective but

provides information on system commands and data

structures. A more intelligent solution based on task

recognition and active coaching (Breuker et al.,

1987) might be more effective but this is still a topic

for future research and development (Delisle and

Moulin, 2002).

The e-learning solution proved to be effective

and should be given preference to classical software

training methods. Contemporary (open source) tools

for developing the e-learning courses turned out to

be useful and effective (cf. Dewever, 2006; Godwin-

Jones, 2012). In addition, using present-day

instructional theories for guiding the instructional

design (Merrill, 2002; Van Merriënboer and

Kirschner, 2013) contributed to good quality e-

learning courses (as perceived by the participants).

For future research we propose two strands of

research. The first strand aims at optimizing the

quality of the e-learning courses. In order to improve

the instruction for coming Psygis Quarant software

updates, an educational design based research

approach (McKenney and Reeves, 2012) will be

used. The second research strand aims at

generalizing findings. Since the results of the present

study are based on a single case in one domain, it is

our intention to replicate the design based research

approach in other domains as well.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The development of the e-learning program

described is a team effort. We would like to thank

the team members for contributing to its success:

Natascha Smeets, Helma Huijnen, Maaike Bos,

Mirièl Troeman and Jan Meinster (Mondriaan

Zorggroep), Wendy Kicken, Marjo Rutjens, Marjo

Stalmeier, and Kees Pannekeet (Open University of

the Netherlands) and Chris Dorna (Chris Dorna E-

learning). We would also like to thank Ine

Verstappen for proof reading.

Contemporarye-LearningasPanaceaforLarge-scaleSoftwareTraining

617

REFERENCES

Breuker, J., Winkels, R., & Sandberg, J. (1987). A shell

for intelligent help systems. In Proceedings of the 10th

IJCAI (pp. 167-173). San Mateo, CA: Morgan

Kaufman.

Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2011). E-learning and the

science of instruction: Proven guidelines for

consumers and designers of multimedia learning (3rd

ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Delisle, S., & Moulin, B. (2002). User interfaces and help

systems: From helplessness to intelligent assistance.

Artificial Intelligence Review, 18, 117-157.

DeRouin, R. E., Fritzsche, B. A., & Salas, E. (2005). E-

learning in organizations. Journal of Management, 31,

920-940.

Dewever, F. (2006) Opportunities for open source

elearning. International Journal of Web-Based

Learning and Teaching Technologies, 1(2), 50-61.

Driscoll, M. (2012). Web-based training: Creating e-

learning experiences (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA:

Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Godwin-Jones, R. (2012). Emerging technologies:

Challenging hegemonies in online learning. Language

Learning & Technology, 16(2), 4-13.

Jochems, W., Van Merriënboer, J., & Koper, R. (Eds.)

(2004). Integrated e-learning: Implications for

pedagogy, technology and organization. New York,

NY: RoutledgeFalmer.

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. C. (2012). Conducting

educational design research. New York, NY:

Routledge.

Merrill, M. D. (2002). First principles of instruction.

Educational Technology Research and Development,

50(3), 43-59.

Pinn-Carlisle, J. (1999). Ethical considerations of the

software-dependent organization. The Journal of

Systems and Software, 44, 251-255.

Shute, V., & Towle, B. (2003). Adaptive e-learning.

Educational Psychologist, 38, 105-114.

Stoyanov, S., & Kirschner, P. A. (2004). Expert concept

mapping method for defining the characteristics of

adaptive e-learning: ALFANET project case.

Educational Technology Research and Development,

52(2), 41-56.

Van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Kirschner, P. A. (2013). Ten

steps to complex learning: A systematic approach to

four-component instructional design (2nd ed.). New

York, NY: Routledge.

Weller, M., Pegler, C., & Mason, R. (2005). Use of

innovative technologies on an e-learning course. The

Internet and Higher Education, 8, 61-71.

Westera, W., Wouters, P., Ebrecht, D., Vos, M., & Boon,

J. (2007). Dynamic probing of educational quality: the

SEIN system. In A. Landeta (Ed.), Good practice e-

learning book (pp. 165-176). Madrid, Spain: ANCED.

CSEDU2013-5thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

618