Organisation, and Information Systems between Formal and Informal

Continuum, Balance, Patterns, and Anti-patterns

Karim Baïna

ENSIAS, Université Mohammed V-Souissi, BP 713 Agdal, Rabat, Morocco

Keywords:

Formal/Informal Organisation, Information System, Formalisation, Over-formalisation, Deformalisation,

Continuum, Balance, Patterns, Anti-patterns.

Abstract:

There is no doubt that formalising information systems is of great value to an organisation. This enables,

among others, business processes, rules, services and objects models to be standardized, structured, capital-

ized and reused. A formal information system involves a structured organisation, clearly defined roles and

responsibilities and therefore a rational management. However, generalising a formalisation approach to all

information system perspectives or all levels of granularity can inversely be fatal to the smooth running of

the business, its management, and operation. The aim of this paper is to explore information systems formal-

informal continuum, to discover and understand its characteristics, patterns, anti-patterns, and the forces part-

cipating to its equilibrium, and to propose recommendations to reach right level of formalisation

∗

.

1 INTRODUCTION

Formalisation

1

- From Object to Form. Through-

out its evolution, man has always used the formali-

sation more or less explicit for his needs of survival,

communication, memory, friendliness, trade, war, etc.

He shared his ideas by gestures and sounds, then

transcribes his ideas and sounds in writing. Then,

he changed his writing system (based on pictograms,

ideograms, and phonograms) and tools for these writ-

ing systems (reed and clay tablet, papyrus, paper).

Long after, man has delegated the reproduction of

his writing he has formalised to machines (inven-

tion of printing). Man then knew mastering energy

by inventing the steam engine he has replaced after

by the electric motor. He made remarkable progress

in all theoretical and experimental sciences (physics,

∗

This work is partially financed by the research grant

EvA (vulgarisation of Enterprise Architecture) n

o

002/EN-

SIAS/2011 of Université Mohammed V-Souissi.

1

To formalise is (i) to give (something) legal or for-

mal status (a year has elapsed since the marriage was for-

malised), (ii) to give a definite structure or shape to (we be-

came able to formalise our thoughts) (OUP, 2012). Formal-

isation for Husserl, is precisely the relationship of an object

to form (Quesne, 2003). (Ostrom, 2009) distinguishes be-

tween rules-in-form (dead letters) and rules-in-use (actually

followed) (Kingston and Caballero, 2009). formalisation

means a reduction in personal and relational elements of

coordination and an emphasis on objectively documenting

decisions, discussions, and work processes (Meijer, 2008).

chemistry, biology, etc., but also economics, psychol-

ogy, sociology, etc.). He has delegated his duties he

has rationalised and formalised by programming ma-

chines to reproduce them faithfully (system automa-

tion, computer science, robotics, etc..), He even for-

malised learning mechanisms and delegated to the

machine tasks of decision making or at least decision

support (application of pattern recognition on events

in critical environments, dashboards and automated

governance of complex systems, application of game

theory in economics, application of bio-medical tech-

nologies, etc.). The evolution continues and with it

the process of formalising ideas. For (Fraser et al.,

1994), formalisation process may be direct (transition

informal to formal) or transitional (transitions infor-

mal to semi-formal then semi-formal to formal).

The aim of this paper is to explore information

systems formal-informal continuum, to discover and

understand its characteristics, patterns, anti-patterns,

and the forces partcipating to its balance.

Human and Formalisation

Example of implicit formalisation - man and bodily

faculties externalisation. According to (Serres et al.,

2004), what is a hammer else than a fist with a fore-

arm, which fell to our arm. The technique was in-

vented by outsourcing a bodily factulty. Actually,

there exists a mechanism that produces continuous

despecialisation of human organs. Human being is

unique in his capacity to lose a faculty and to develop

85

Baïna K..

Organisation, and Information Systems between Formal and Informal - Continuum, Balance, Patterns, and Anti-patterns.

DOI: 10.5220/0004401000850093

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 85-93

ISBN: 978-989-8565-60-0

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

others. In instrumenting, and transforming his body,

the human is involved in a endless loop of transsub-

stantiation that is transmitted by using technical ob-

jects (Serres, 2001). In fact, externalising his or-

gans to objects (first hominescence loop), humanity

has freed itself from species adaptation mechanisms

(exodarwinism). Invention of first tools has freed

human being from evolution towards culture. Since

the technique appears, the human exit from evolutive

laws, his body changes sparsely, but his adaptation

becomes very quick. We believe that bodily facul-

ties externalisation includes, among others, a contin-

uous formalisation mechanism of ("defining a shape

to" (Quesne, 2003)) objects, tools, and processes nec-

essary to achieve human tasks.

Example of Explicit Formalisation - Human Writing

Systems. According to (Wilson, 2005), all writing

systems followed the same general progression. The

first actual writing was pictographic or iconographic

where a simple picture designated a real object. Gen-

erally the pictures were very simple and abstractions

of what we might think of as a drawing (a drawing of

a deer represented a real deer). A stylised picture is

called a pictogram. Gradually the pictures were for-

malised and also began to be used to represent rela-

tionships and ideas as well as objects. This is called

ideographic writing. A symbol standing for an idea

is a semantic sign and is called an ideogram or lo-

gogram (a picture of the moon could represent the

idea of night or darkness as well as that of the moon

itself). Also, the sounds corresponding to pictograms

are combined to form a word. This can markedly re-

duce the number of symbols required for a full writ-

ing system. Symbols representing sounds are called

phonograms. All writing systems are a combination

of phonetic and logographic elements but the propor-

tions of these two elements vary among languages

(for instance, French and Finish are more phonetic

than English, while, Chineese and Japaneese are more

ideographic). We think that all informal, semi-formal

and formal languages, and notations used to represent

information systems, are only results of this continu-

ous process of writing system formalisation based of

pictograms, ideograms, and phonograms.

Formalisation - From Human to Entreprise Activ-

ity. If man is the heart of the enterprise, any analysis

of phenomena in this business cannot be conducted

without considering the evolution of man from micro

and macro viewpoints. Thus, could not we make the

analogy between the development of the enterprise

and the development of man both as an individual

and a species? Could not we make the analogy be-

tween the analysis of the formalisation aspects in the

enterprise and the study of the formalisation evolution

accompanying human species evolution? The analy-

sis of human development was conducted using two

approaches: micro and macro. The microscopic ap-

proach (ontogeny) focuses on human individual bio-

logically and psychologically from conception, birth,

development, maturity, aging until his death. As for

the macroscopic approach (phylogeny), it analyses

man development as reproducing the evolution of the

human species in relation to his instincts, reflexes,

emotions, language development, motor skills, biped

posture, games, intelligence, interaction, social life,

ledearship, etc. We will look at the second point of

view to try to understand the enterprise through the

evolution of man in a macroscopic scale. Businesses

did not they (i) start by improving their oral cul-

ture and visual communication (sounds and ges-

tures) internal (customs, rumors, discussions, meet-

ings, etc.) and external (corporate identity, adver-

tising slogans, informal marketing, communications

and audio-visual marketing, etc.).? Then, companies,

did not they (2) develop their written culture either

formalised (official letters, orders, hierarchical esca-

lation, coorporate public communication, newspaper

articles, patents, etc.) or informal (or rather defor-

malised: e-mail, web 2.0, blogs, vblogs, wiki, pro-

fessional social networking, etc.).? Companies, did

not they, for capitalising their memory, standardis-

ing their interactions, and controlling the quality of

their products and services, (iii) opt for cartography-

ing their knowledge, strategic know-how, and their

operational information systems (business and or-

ganisational visions and strategies, knowledge, qual-

ity manuals, management processes, business pro-

cesses, business rules, procedures) in a semi-formal

style based on pictograms and ideograms (graphic no-

tation and symbolic with flexible semantics)? Did

not they, since the advent of information technology

and communications, (iv) project their information

system into more formal electronic and computer

frames (physical computer infrastructures, telecoms,

networking and embedded systems, security direc-

tories, rules engines, computer applications, gover-

nance dashboards, etc.) in order to be automated,

measurable and therefore improvable? Table 1 shows

some artifacts examples having evolved through a for-

malisation process.

2 INFORMATION SYSTEMS

BETWEEN FORMAL

AND INFORMAL - MODEL

We will never over emphasis on the formalising power

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

86

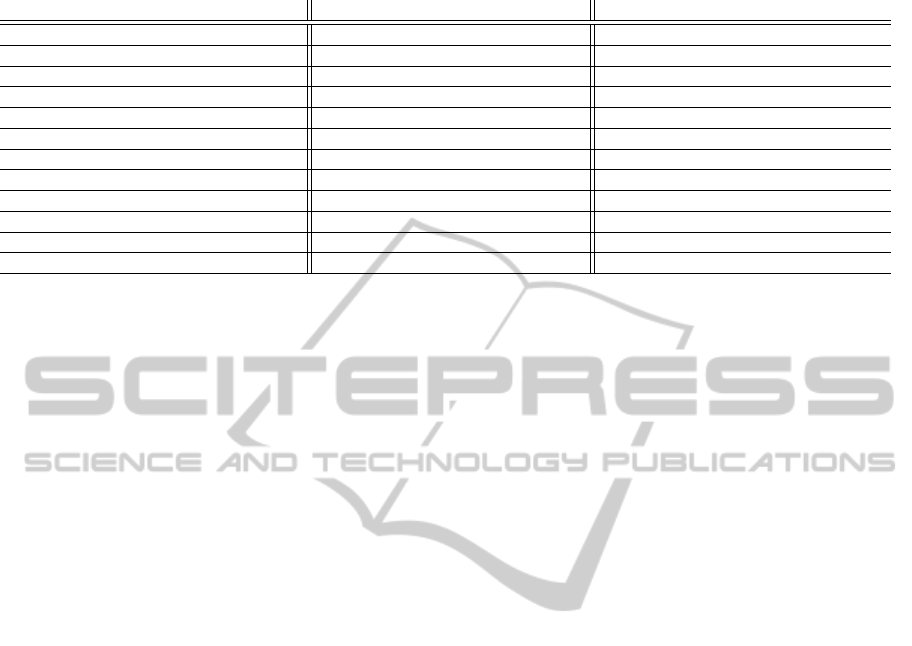

Table 1: Examples of artifact evolution at entreprise level and their formalisation process.

Origin artifact Purpose of formalisation formalised artifact

oral culture preservation of knowledge writing culture

paper data dematerialisation digital data

handwriting externalisation of bodily faculties printed writing (keyboard)

information system modelling information systems models

manual procedure dematerialisation & automation automatic procedure

real information system automation virtual computer system

line work dematerialisation & automation automated process

physical (in-house) computer system virtualisation & outsourcing virtual (out-house) computer system

real bank counter virtualisation automated teller machine

real agency virtualisation virtual office (online)

real money virtualisation electronic money

real machine virtualisation virtual machine

of informal style. In fact, it is, often better, to pre-

fer the informal style instead of semi-formal or even

formal styles to provide a good knowledge descrip-

tion, sharing, sustainability, implementation and op-

eration. Do not they say, "A picture is a thousand

words"? According to (Renaud, 1995), (Enriquez,

1990) has noted: "Organisations have never been only

formal, functional, impersonal. Even in the most rigid

bureaucracies, there exist informal relations, groups

based on elected affinities, on the work necessity, on

the circumvention of rules, or collective defense. Any

organisation contains within itself diverse communi-

ties, micro-cultures and is a place to live not just a

workplace". (Stamper et al., 2000) highlights that or-

ganisations that learn most easily are often those able

to work well informally. He adds that classical meth-

ods tend to increase the proportion of formality in an

organisation without drawing attention to the possi-

bility of meeting requirements by improving or ex-

tending the informal part of the organisation. For

(Schmidt and Bannon, 1992), no formal description

of a system (or plan for its work) can be complete.

The formal is best used for predictable and repeat-

able work that needs to be done efficiently and with

little variance. The predictability and repeatability of

the work warrants the effort to develop the infrastruc-

ture of the formal organisation, which can be docu-

mented and constantly improved upon to improve ef-

ficency and remove variation. Many of formal pro-

cesses and tasks can be and have been implemented

over the years. Payroll distributions are a good exam-

ple. Conversely, the informal is best applied against

unpredictable events. Issued that arise outside the

scope of the formal organisation are often surprises

that need to be sensed and solved. Increasingly, pe-

pole who need to do the solving need to be motivated

outside the reward system, collaborate across organ-

isational boundaries. Every organisation must deal

with both predictable and unpredictable work, that is

why it is necessary to learn how and when to call on

the logic of the formal and balance it with the magic

of the informal (Katzenbach and Khan, 2010).

The information that must be distributed in a hu-

man activity system indicates that two separate infor-

mation systems must be considered. One is imple-

mented through policies and processes (that is, the

formal information system), whereas the other (the

informal information system), ties the people in the

organisation together. If something goes wrong with

the formal system, we still need experimented people

to fix it (Flatau, 1988).

Informal information systems complement formal

systems. They are more spontaneous and provide

for flexibility and adaptation yet they may themse-

leves suffer from bias and noise. The key design

decision is where to draw the line between the for-

mal and informal and to monitor continuously the

dividing line. This may mean, on occasions adopt-

ing an unofficial system and formalising it, or ceas-

ing to produce information which becomes inappro-

priate (Lucey, 2005). For (Howarth, 2005), formal

information systems consist of rules and procedures,

while informal information systems rely on common

practice and common sens of the organisation’s em-

ployees. Informal information systems usually arise

from restraints or inadequacies of the formal system.

By filling in the gaps in the formal system, the in-

formal system creates an added flexibility to the way

in which the organisation functions. Ideally, the two

systems should complement one another. However,

unless managers monitor the interaction between the

two systems to ensure that they are working together

effectively, there is a danger in having the two systems

(Howarth, 2005).

Formal Information systems (particularly infor-

mation retrieval systems) are developed to be con-

sulted and queried in purposeful ways, meaning that

users must have some idea of what they need to know.

While, informal information systems generally evolve

from the bottom up rather that the top down, emerg-

Organisation,andInformationSystemsbetweenFormalandInformal-Continuum,Balance,Patterns,andAnti-patterns

87

ing directly from the community of users. By the

way, even if teanagers do not clearly differentiate be-

ween informal and formal information environments,

it certainly appears that formal information systems

are loosing out with the teen audiance who use them

only when required to (Harris, 2011).

This section studies duality, continuum and bal-

ance between formal & informal and between formal

& informal information systems in particular.

2.1 Informal - Formal: Duality

The contribution of informal is undeniable for the

enterprise, it complements the formal. In (Renaud,

1995), informal (badly named) is not a "complemen-

tary" resource that should be "formalised and ratio-

nalised", the form hits the formlessness which makes

it live. For instance, informal communication chan-

nels complement the formal communication channels

when they are no longer sufficient or are no longer

adequate (Amosse et al., 2010). Also, instead of de-

structuring effects by which the informal sector is des-

ignated, it is its complementarity with formal mech-

anisms that is nowadays highlighted, which signifi-

cantly alters the approach to problems (Désert, 2006).

Companies that balance between their formal and

informal organisations, retain the efficiency and clar-

ity of the well-defined structures that define the for-

mal organisation while also capitalising on the flexi-

bility and speed of the social networks (Katzenbach

and Khan, 2010). (Renaud, 1995) calls the formal

and informal a "notional couple" where one does not

combine without the other. According to (Kingston

and Caballero, 2009), for the first half-century of its

existence Lloyd’s insurance operator had virtually no

formal structure at all, and when a formal structure

was eventually created, largely as a result of the im-

petus provided by the Napoleonic wars, formal rules

were adopted mainly to systematise a practice which

had already been adopted to meet the requirements of

commerce as they arose. Even then, informal rules

and reputation mechanisms (not written down, ethi-

cal codes or moral, social norms and conventions) re-

mained the dominant mode by which participants at

Lloyd’s were constrained from opportunistic behav-

ior. Business practices which evolved acquired the

force of informal custom long before they were sys-

tematised as formal rules.

According to (Foudriat, 2007), the extent and na-

ture of the informal have led some theorists to propose

a metaphor comparing the organisation to an iceberg,

where the emergent part corresponds to the formal as-

pects (behavior related to the organisations scientific

approach), while the submerged part, consists of indi-

viduals strategies, affective ties, coalitions of groups,

power relations. (Foudriat, 2007) studied informality

in three views:

For scientific management (Taylorism) single ra-

tional point of view, the informal is considered as a

temporary residual rationality deficit that new formal

rules will reduce or to remove. While human relations

school (including surveys of Elton Mayo at Western

Electric), considers that the informal includes goals

and psychological needs of individuals which can nei-

ther be filled, nor reduced, nor manipulated by ratio-

nal logics, and which are in shift with the local order

that the formal organisation seeks to impose. Infor-

mal and formal are two opposite and irreducible sides

of the the organisational phenomenon. For systemic

and strategic analysis ((Crozier and Friedberg, 1977)

surveys), the informal is not limited to the psycho-

logical needs of individuals, but includes the inter-

ests centered power games that individuals find in the

formal organisation. Informal behaviors are seen as

strategies.

We believe that each formal system, has and

depends on a dual informal system (complemen-

tary image) more important (duality or dichotomy).

Both systems evolve in parallel and interact con-

tinously. There exist several examples of for-

mal/infomal duality in the entreprise. The idea of

the duality of formal/informal information systems is,

by no means, a simplistic binary polarity of informa-

tion systems states, but a consideration of the possi-

ble levels of formalisation of information systems be-

tween the two limits: over-deformalisation and over-

formalisation. Evaluation of this duality is closely re-

lated to the size and business of each organisation or

part of organisation (department, business unit, etc.)..

The following sections are intended to define the dif-

ferent concepts characterising this duality.

2.2 Informal - Formal: Characteristics

Degree of Formalisation/Deformalisation. The for-

malisation (respectively defomalisation) degree of a

system is a qualitative value that evaluates on a dis-

crete scale its level of formalisation (respectively

deformalisation). The level of formalisation is an

attempt to model discrete steps defined in a uni-

verse of infinite posibilities between two limits: over-

deformalisation and over-formalisation. The degree

of formalisation (deformalisation respectively) may

be called "degree/level of standardisation" (Hughes

et al., 2005; Ross et al., 2006) (respectively defor-

malisation (Delzescaux, 2002)). (Hughes et al., 2005)

mentions that the degree of formalisation of an organ-

isation depends on its size and nature of work (for in-

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

88

stance, a production unit cannot have the same degree

of formalisation that a unit of R&D).

Gap between Formal and Informal. The formal-

informal gap is the difference between the degree of

formalisation and deformalisation of a system and its

dual at a given time (peak-to-peak - ptp). The gap is a

discrete value not necessarily positive. (Delzescaux,

2002) calls this gap "synchronic" (as opposed to "dy-

achronic gap" which measures the difference between

formal and informal systems at two different instants

in time). Furthermore, (Delzescaux, 2002) noted that

the larger the gap in society, the greater the distinc-

tion between social classes (one could project this gap

on the depth of a hierarchy in an organisation, that

(Hughes et al., 2005) called vertical complexity of

an organisational structure). (Delzescaux, 2002) adds

that the reduction of this gap indicates a shift in the

balance of power (which we will define later as the

center of gravity of the couple formal / informal).

Centre of Gravity of Formal-informal Couple. The

center of gravity of formal-informal system couple

is a point representing the balance of power between

formal and informal. (Renaud, 1995) says the forms

are not of the same rigor, the same mass, the same

power of attraction and energies conformation. Be-

tween volunteering and professional relationship, be-

tween the community and the public network, there

is a mass difference, that when it differs, the attrac-

tion/conformation are changing from one to another.

The center of gravity of formal-informal couple fol-

lows the metaphor of the formal / informal iceberg

evoked by (Foudriat, 2007). In fact, moving the cen-

ter of gravity of an iceberg is sufficent for the iceberg

to capsize or roll on itself. We can confirm this anal-

ogy through (Delzescaux, 2002) who talks about the

balance of formal/informal power. Indeed, shifting

the center of gravity of the couple formal/informal is

a characteristic of a regulation (search for the balance

of forces governing them).

Trail of Formal-informal Couple. The area delim-

ited by fomal and informal systems time evolution de-

fines the trail of formal-informal system couple. The

trail records the different levels of information sys-

tems formalisation. If an information system is at a

certain level of formalisation, behaviours of differents

actors of this information system should be consid-

ered not only through the current formalisation level,

but also through (1) the whole history of informa-

tion system formalisation, (2) the history of dual in-

formal information system formalisation, and (3) the

trail contained between the two formalisation evolu-

tion histories.

2.3 Informal - Formal: Continuum

Complementarity between formal and informal sup-

ports a kind of it continuum which ensures the move

from one to the other in a continuous way. If the tran-

sition from informal to formal is insured by formali-

sation, the dual transition from formal to informal is

provided by deformalisation. Knowledge deformali-

sation, according to (Volckrick and Deliège, 2001) is

to defer the weight of problems and conflicts resolu-

tion mainly on participating parties (e.g., for (Deliège,

2010), knowledge deformalisation is also reflected in

the fact that the patient become himself well informed

about his illness, or on the fact that all the actors in-

volved in a problematic claim as legitimate their point

of view and "experience know how" on some situa-

tion). In addition, justice procedures deformalisation

is easing rules by the players or the law itself (Cadiet,

2008). Table 2 shows some examples of formal arti-

facts deformalisation.

Based on the work of (Crozier and Friedberg,

1977), (Livian, 2004) emphasizes that there is a close

relationship between formal and informal. In fact, in

learning situations, for example, deformalising for-

mal is taking the risk to formalise what is by nature in-

formal (over-formalisation duality) (Brougère, 2007).

Thus, replacing traditional training situations (formal

artifact) by less formal projects debrieffing situations

(intermediate situation between formal & informal) is

trying to transform informal learning activities (dual

informal artifact) to in more framed learning while

one cannot eliminate the role of informal learning.

According to (Kingston and Caballero, 2009) in-

formal constraints are the major source of institutional

(formal) inertia, because (i) they continue to exist

within formal rules that they were prior configura-

tions, and (ii) they change in an incremental slow evo-

lution. The influence of informal on formal rules is

not wholly conservative, cultural endowments can ac-

tually make some kinds of institutional change easier.

He gives the example of Japan, where he argues that

traditional patterns of cooperation which emerged in

the distant past facilitated modern rural development

programs. (Kingston and Caballero, 2009) highlights

the importance of temporal dimension when he con-

sideres the role of the whole organisation past evolu-

tion systems current change. Thus, formalising pro-

cess is not a choice but an evolution.

One can deduce, with generalisation, that defor-

malising a formal system returns to formalising its

dual informal system (negative correlation). This

type of correlation can also connect systems not nec-

essarily formally dual. Also, ability to formalise a

system depends on the preparation of other infor-

Organisation,andInformationSystemsbetweenFormalandInformal-Continuum,Balance,Patterns,andAnti-patterns

89

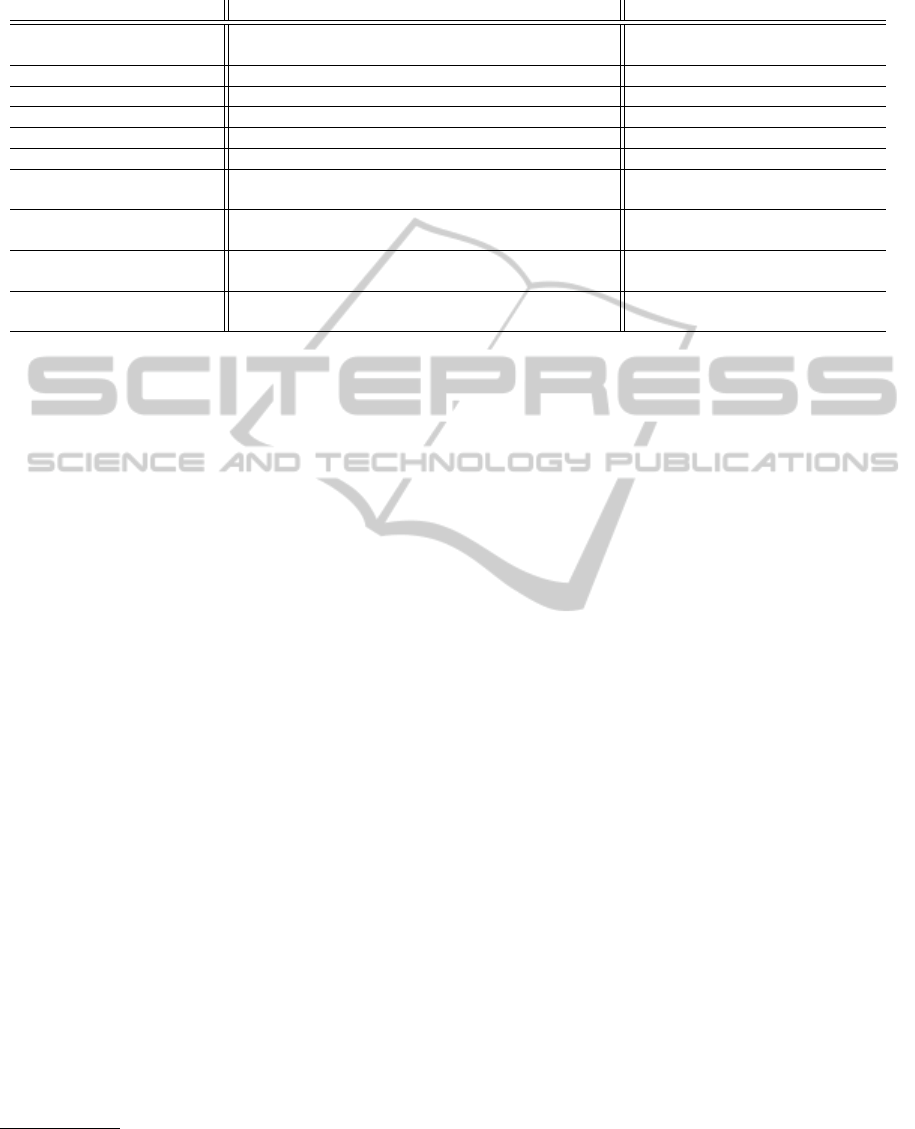

Table 2: Examples of deformalisation processes in organisations.

Formal artifact Purpose of deformalisation deformalised artifact

"formal" hierarchical mail make bureaucratic communication more flexible "informal formalisation" (e-mail)

(Meijer, 2008))

autocratic management involve the group in decision making permissive management

classical innovation put the individual/user in the center of innovation open innovation

classical leraning democratise access to knowledge & cost sharing e-learning

personal computers favor mobility intelligent tablets

real networks banalise professional networking virtual networks

workflow give more freedom to the user handle the unpre-

dictible

groupware & advanced case

management

web with passive users,

etc.

integrate social dimension & crowdsourcing in

knowledge production

web 2.0 with wiki, etc.

SOAP + WS-* web ser-

vices

reduce dependences to protocols & static formats RESTful web services (light

stack)

relational databases efficient & scalable data storage for distributed en-

vironment

NoSQL (Not Only SQL)

databases

mal systems on which it depends (positive correla-

tion). In this continuum between formal and infomal,

there exists a dynamics acting between formal and

informal systems in space and time.

3 INFORMATION SYSTEMS

BETWEEN FORMAL AND

INFORMAL - BALANCE,

PATTERNS, AND

ANTI-PATTERNS

If there exist a continuum between formal and infor-

mal, dynamics of this continuum is governed by a

regulation of power between different systems pro-

ducing a state of stable equilibrium. If research

works affirm the existence of this equilibrium (bal-

ance) (e.g., (Hesse and Verrijn-Stuart, 2000; Purao

and Truex, 2004; Ailawadhi and Heller, 2010)), they

do not study the problem in depth and think that for-

malisation can respect that balance through a deci-

sion rather than considering power evolution between

formal and informal systems

2

. Certainly, we must

choose a useful and pragmatic formalisation (neces-

sary and sufficient) rather than a purpose-less formal-

isation, disconnected from the priority needs of in-

progress projects, but what is more important is to

consider the whole organisation eco-system in a sys-

temic (holistic) vision.

We believe that the continuum between formal-

informal information systems finds its balance

2

(Ailawadhi and Heller, 2010) offers a best practice to

achieve this level of formalisation just by modeling just-

time (JIT) just-enough architecture that reflects the business

requirements and technical available resources.

through regulation cycles of those informa-

tion systems (series of oscillations formalisation-

deformalisation until an equilibrium position). Levels

of insufficient-formalisation or over-formalisation are

relative thresholds that vary over time. Also, infor-

mation systems cannot be compared against a level

of formalisation except if they have the same char-

acteristics and evolve in the same context. Regula-

tion between formal-informal information systems re-

spects the formal/informal iceberg metaphor evoked

by (Foudriat, 2007). Moreover, a floating body (e.g.

a ship) does not hold for a moment its stable state,

but it continuously oscillates around this state. More

particularly, the movement of an iceberg depends on

its characteristics (density, thickness, shape) and is af-

fected by external phenomena: ocean currents, winds

push, wave action (when storms), Coriolis force (ice-

berg drift). Also, each iceberg has its own iceberg

oscillation period depending to its characteristics and

movements of its center of gravity enough to capsiz-

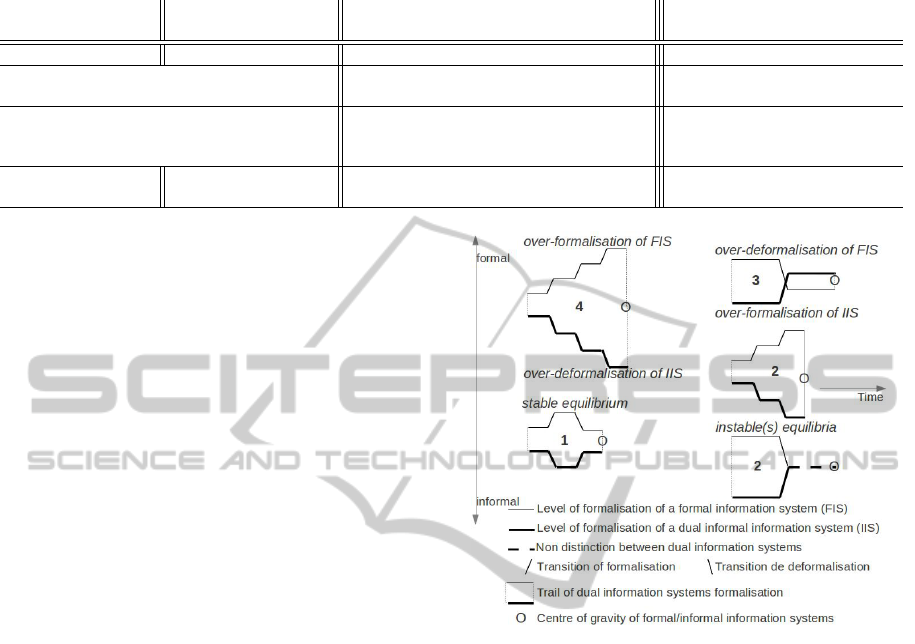

ing or rolling. Figure 1 shows four states of the dual

formal/informal information system couple including

three anti-patterns.

1. Formal/Informal Stable Equilibrium: deformal-

isation of a formal information system leads to a logi-

cal and normal deformalisation of dual informal infor-

mation system and vice versa without neither impor-

tant gap nor overlap (i.e. neither instability nor over-

fomalisation/over-deformalisation). The application

of the iceberg metaphor means that the center of grav-

ity of the formal/informal couple remains stable. The

state of stable equilibrium represents a highly desired

situation (pattern). (Ring and van de Ven, 1994) de-

notes the formal/informal equilibrium state as a sit-

uation of organisational cooperation. (Katzenbach

and Khan, 2010) mentions that managers, are able

to motivate their people to higher levels of perfor-

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

90

mance, not by enslaving workers with rigid top-down

metrics or by being nice to all and making friends.

Their approaches were neither hard nor soft. Instead

they took the best of both the formal and informal or-

ganisations and integrated them to drive their people

and partners to a shared purpose. While on a business

trip to China, a manager of Bank of America was no-

tified about an exceptional performance accomplish-

ment at TeleTech. He wanted to congratulate every-

body, which meant schedulting a call during a shift

change. The only time he could arrange that was at

3AM local China time. The fact that Sheehy would

make a call at that hour made his words of congratula-

tion all the more meaningful to the TeleTech employ-

ees. In just a few months, TeleTech’s call center rose

from last place to fist place among BofA’s call centers.

While Gregg Sheehy has very little formal authority

on TeleTech staff, he could find a balance between

formal imperatives with informal mechanims in ways

that would create the emotional commitment and en-

ergy needed to change behaviors to push Teletech up

the ladder of performance results.

2. Formal/Informal Instable Equilibria: there are

two kinds of instable formal/informal equilibria, (i)

the first is characterised by a deformalisation of a for-

mal information system that meets the formalisation

of an informal dual system so that we no longer dis-

tinguish the two dual systems (zero formal/informal

gap). Instability comes from the fact that this gap may

become negative and cause an over-deformalisation

of the formal information system. (ii) The second

instable formal/informal equilibrium is characterised

by successive information system formalisations that

may yield, if repeated, an over-formalisation of the

formal information system. Unless managers moni-

tor the interaction between the formal and informal

systems to ensure that they are working together ef-

fectively, there is a danger in having the two sys-

tems (Howarth, 2005). (D’Adderio, 2003) mentions

that the interactions between formal tools and infor-

mal practices can be described as a fragile, unstable

equilibrium, characterised by never-ending frictions,

loose ends, and unforeseen consequences. While de-

vices or routines may be created to ’fix’ recurrent

tensions, these will also tend to generate new prob-

lems. (Gerrard et al., 2001) warns against the over-

formalisation and over-institutionalisation by promot-

ing creative situations known to be instable, chaotic

and disorderly and maintaning a kind of structured

informality. States of instable equilibria are called

"chaos border area" by (Stacey, 1992) and are known

to be states of creativity and innovation.

3. Over-deformalisation of Formal Informal Sys-

tem: deformalisation of formal information system

drops below the minimum informal limits for formal

system for this system (this leads to a formalisation of

the dual informal system beyond the maximum for-

mal limits for informal system -over-formalisation

of informal IS-). State of over-defomalisation is an

anti-pattern. Suppose the organisation moves into a

new market or increases its workforce so that the na-

ture of the organisation is changed or developed in

some way. The flexibility created by the informal sys-

tem allows the changes to be accomodated without

any revision to the formal system. This is acceptable

up to a point, but, it means that the informal system

is overriding the formal system and therefore the ef-

fectiveness of the formal system has decreased. As a

result, the managers’ knowledge of the way in which

the organisation functions has decreased. This means

they have lost control to some extent (Howarth, 2005).

We categorise the state of over-deformalisation as a

chaos state by (Stacey, 1992).

4. Over-formalisation of Formal Informal System:

formal information systems follow a succession of

formalisations more and more complex without any

regulation (this leads to deformalising the dual in-

formal information system in the same pace -over-

deformalisation of informal IS). The causality may

be reversed: (2) may precede and yield (1). This

state is characterised by an abnormal growth of for-

mal/informal gap. State of it over-defomalisation is

an anti-pattern. (Gerrard et al., 2001) describes over-

formalisation as "the obsession by the processes in-

stead of results." (Lewis et al., 2010) adds that over-

formalising the collaboration can impede what a few

informants called the open dialogue of the collabo-

rative process. Regimented agendas and too many

subcommittees were common symptoms of an over-

formalised collaboration. We categorise the state of

over-formalisation as a chaos and messiness state by

(Stacey, 1992).

Even if we take the notion of "chaos" from

(Stacey, 1992), we do not agree with him on sev-

eral points of classification of business states. While,

R. Stacey highlights the equal importance of formal

and informal organisations and advises managers to

consider both formal processes and structures and in-

formal systems, he did not study the subtleties be-

tween formalisation and over-formalisation and their

dual state deformalisation and over-deformalisation.

He badly transcribed this duality as he called nonlin-

ear feedback system when it defines a linear transition

relationship between chaos, instable equilibrium and

stability flattening formal/informal duality. This flat-

tening pushes R. Stacey to qualify the state of over-

formalisation (that he called "ossification") as a state

of stability and state of over-deformalisation (that he

Organisation,andInformationSystemsbetweenFormalandInformal-Continuum,Balance,Patterns,andAnti-patterns

91

Table 3: Semantics of formal/informal states.

Formal system

state

Dual informal sys-

tem state

Semantics (Stacey, 1992) Enterprise

state semantics

over-formalisation over-deformalisation obsession by processes instead of results

instable equilibrium endless frictions between formal & in-

formal

chaos border: tensions & in-

novations

stable equilibrium organisational cooperation & regulation

of powers

stability: harmonious, or-

derly & with previsible repe-

titions

over-

deformalisation

over-formalisation loss of control chaos:paradoxal, conflitual,

fractal & infinitely creative

called "disintegration") as a state of instability. How-

ever, the two states in terms of formalisation, are dual

chaotic states, one testing the limits of form and the

other testing the limits of formless. The same flat-

tening, pushes R. Stacey to consider a single state of

chaos, certainly unpredictable, but rich of conflicts,

paradoxes, and innovations counter-balancing the sta-

ble equilibrium state. Thus, R. Stacey has considered

only a single instable equilibrium state, in middle way

between chaos and instability, characterised by ten-

sions predicting the chaos. The fact that he ignored

the formal/informal dualilty in his classification, it

was forgotten that the stable equilibrium is, in turn a

middle way between formal and informal instability.

4 CONCLUSIONS

AND PERSPECTIVES

Computing, based on mathematical rigor and ratio-

nality of scientific management, has strongly inher-

ited of the defect of formalising and rationalising ev-

erything, even the most ordinary tasks or the most

unique events. This excessive use of meta, axiomati-

sation, and abusive rationalisation has exceeded hard

sciences to reach also social sciences (economics,

management, psychology, etc.). As far as we study

this phenomenon from information systems formali-

sation point of view, companies can be found in five

different states: two extreme states (i) state of over-

formalisation and (ii) state of over-deformalisation,

(iii) one state of formal/informal equilibrium, and (iv)

two states of instable equilibrium, the first predicting

formal instability, and the other predicting informal

instability. The purpose of this paper is to highlight

the importance of the informal, and to study infor-

mation systems formal/informal duality, continuum,

and formalisation patterns and anti-patterns charac-

terising formal/informal regulation cycles. The origi-

nality of this work is its approach genericity towards

formal/informal enterprise facets, which ensures its

applicability to study several problems. Our current

Figure 1: Correlation between dual systems in all states.

works aim to apply our model to organisational and

technical problematics within enterprises.

REFERENCES

Ailawadhi, A. and Heller, P. (2010). An oracle

white paper in enterprise architecture – soa anti-

patterns: How not to do service-oriented architecture.

http://www.oracle.com.

Amosse, T., Guillemot, D., Moatty, F., and Rosanvallon,

J. (2010). Échanges informels et relations de tra-

vail à l’heure des changements organisationnels et

de l’informatisation. Number 60 in Rapports de

recherche du CEE - Centre de l’étude de l’emploi.

Brougère, G. (2007). Les jeux du formel et de l’informel.

Revue française de pédagogie, (160):5–12.

Cadiet, L. (2008). Case management judiciaire et dé-

formalisation de la procédure. Revue française

d’administration publique, (150):133–150.

Crozier, M. and Friedberg, E. (1977). L’acteur et le système.

Seuil, Paris.

D’Adderio, L. (2003). Bridging formal tools with informal

practices: How organisations balance flexibility and

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

92

control. In DRUID Summer Conference 2003 on Cre-

ating, Sharing and Transferring Knowledge. The role

of Geography, Institutions and Organisations, Copen-

hagen, Danemark.

Deliège, I. (2010). Articulation des savoirs professionnels

et de l’usager dans un réseau d’intervenants psycho-

médico-sociaux. Santé et Sciences Sociales - Commu-

nication et santé: enjeux contemporains, pages 17–

28.

Delzescaux, S. (2002). Norbert Elias: civilisation et dé-

civilisation. Logiques sociales: Série Sociologie de la

connaissance. Harmattan.

Désert, M. (2006). Le débat russe sur l’informel. Num-

ber 17 in Questions de Recherche / Research in Ques-

tion.

Enriquez, E. (1990). les enjeux éthiques dans les organisa-

tions modernes. Sociologie Sociétés, XXV(1).

Flatau, U. (1988). Designing an information system for in-

tegrated manufacturing systems. In Compton, D., edi-

tor, Design and Analysis of Integrated Manufacturing

Systems, pages 60–78. National Academy Press.

Foudriat, M. (2007). Sociologie des organisations. Pearson

Education France.

Fraser, M. D., Kumar, K., and Vaishnavi, V. K. (1994).

Strategies for incorporating formal specifications in

software development. Commun. ACM, 37(10):74–

86.

Gerrard, C., Ferroni, M., and Mody, A. (2001). Global Pub-

lic Policies and Programs: Implications for Financ-

ing and Evaluation: Proceedings from a World Bank

Workshop. Commodity Working Papers. World Bank.

Harris, F. J. (2011). I found it on the internet, coming of age

online, 2nd edition. American Library Association.

Hesse, W. and Verrijn-Stuart, A. A. (2000). Towards a the-

ory of information systems: The frisco approach. In

Tenth European-Japanese Conference on Information

Modelling and Knowledge Bases (EJC’2000), pages

81–91, Saariselkä, Finland. Information Modelling

and Knowledge Bases XII, IOS Press, Amsterdam,

The Netherlands.

Howarth, A. (2005). Information Systems Management,

Cambridge International Diploma in Management at

Higher Professional Level. Select Knowledge Lim-

ited.

Hughes, R., Ginnett, R., and Curphy, G. (2005). Leader-

ship. McGraw-Hill Education.

Katzenbach, J. and Khan, Z. (2010). Leading Outside the

Lines: How to Mobilize the Informal Organization,

Energize Your Team, and Get Better Results. John Wi-

ley & Sons.

Kingston, C. and Caballero, G. (2009). Comparing theo-

ries of institutional change. Journal of Institutional

Economics, 5(2):151–180.

Lewis, L., Isbell, M. G., and Koschmann, M. (2010).

Collaborative tensions: Practitioners’ experiences of

interorganizational relationships. Communication

Monographs, 77(4):460–479.

Livian, Y.-F. (2004). Les structures organisationnelles. In

Lancry, E. B. A. and Louche, C., editors, Les Dimen-

sions Humaines du Travail - Théories et pratiques de

la psychologie du travail et des organisations, pages

335–358. Presses Universitaires de Nancy.

Lucey, T. (2005). Management Information Systems, 9th

edition. Thomson Learning.

Meijer, A. J. (2008). E-mail in government: Not post-

bureaucratic but late-bureaucratic organizations. Gov-

ernment Information Quarterly, 25(3).

Ostrom, E. (2009). Understanding Institutional Diversity.

Princeton Paperbacks. Princeton University Press.

OUP (2012). Oxford dictionaries. http://

oxforddictionaries.com/.

Purao, S. and Truex, D. P. (2004). Supporting engineer-

ing of information systems in emergent organizations.

Information Systems Research, Relevant Theory and

Informed Practice, 143.

Quesne, P. (2003). Les Recherches Philosophiques Du Je-

une Heidegger, volume 171 of Phaenomenologica.

Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Renaud, G. (1995). Le formel et l’informel : une tention

créatrice continuelle. Théologiques, 3(1):129–152.

Ring, P. S. and van de Ven, A. H. (1994). Developmental

processes of cooperative interorganizational relation-

ships. Academy of Management Review, 19(1):90–

118.

Ross, J., Weill, P., and Robertson, D. (2006). Enterprise

Architecture As Strategy: Creating a Foundation for

Business Execution. Harvard Business School Press.

Harvard Business School Press.

Schmidt, K. and Bannon, L. (1992). Taking CSCW Seri-

ously: Supporting Articulation Work. Computer Sup-

ported Cooperative Work, 1:7–40.

Serres, M. (2001). Hominescence. Le Pommier, Paris.

Serres, M., Atlan, H., Omnès, R., Charpak, G., Mongin,

O., Dupuy, J.-P., and Canto-Sperber, M. (2004). Les

Limites de l’Humain, volume XXXIX (2003) of Ren-

contres Internationales de Genève. L’Age d’Homme,

Lausanne, Suisse.

Stacey, R. (1992). Managing the Unknowable: Strategic

Boundaries Between Order and Chaos in Organiza-

tions. Jossey-Bass Management Series. Jossey-Bass.

Stamper, R., Liu, K., Hafkamp, M., and Ades, Y. (2000).

Understanding the roles of signs and norms in organ-

isations - a semiotic approach to information systems

design. Journal of Behaviour & Information Technol-

ogy, 19(1):15–27.

Volckrick, E. and Deliège, I. (2001). Savoirs formels

et savoirs informels, une approche pragmatique.

Recherches en communication, (15).

Wilson, P. (2005). Philology - the alphabet tree. TUGboat,

26(3):199–214.

Organisation,andInformationSystemsbetweenFormalandInformal-Continuum,Balance,Patterns,andAnti-patterns

93