Energy Informatics Can Optimize the Design of Supply and Demand

Networks

Robert Bradshaw

1

and Brian Donnellan

2

1

National University of Ireland Maynooth, Maynooth, Ireland

2

National University of Ireland Maynooth, Innovation Value Institute, Maynooth, Ireland

Keywords: Green IS, Supply and Demand, Networks, Sustainability, Energy Informatics, Bikeshare.

Abstract: This paper proposes that a new green IS framework – Energy Informatics – may provide the best means of

optimising the design of supply and demand networks. The framework proposes an integrated systems

solution which incorporates technical and architectural design elements, eco-goals, and human stakeholders

and places a particular focus on the role of information systems in effectively integrating and managing

service supplier and service user information to optimize network efficiency. The paper explores the

potential of the framework through a case study of an innovative bikeshare initiate from MIT called The

Copenhagen Wheel. The study demonstrates that the framework has the potential to inform system design in

the bikeshare domain. Further research will be required to determine its potential in informing other supply

and demand areas.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

A recurring theme in the sustainability literature is

our continued reliance on the burning of fossil fuels

for energy production. The consequence of this has

been a significant increase in atmospheric carbon

dioxide which in turn has resulted in a range of

problems including air pollution, ocean acidification

and a loss of biodiversity (Jacobson, 2008). A broad

consensus exists amongst scientists and social

commentators alike that reducing our levels of CO

2

will be pivotal in addressing these problems. The

response from businesses and corporations in

particular, given their importance within our

societies is increasingly seen as key to the success of

the sustainability agenda. Due to the close attention

of the media, lobbyists, and an increasingly eco-

conscious public, all areas of corporate activity have

now come under scrutiny and businesses are

expected to be far more proactive, and indeed

creative, in how they meet their sustainability

obligations.

The information systems community has

responded to this changing climate by exploring the

potential of technology to work in conjunction with

people, processes and business practices to deliver

holistic solutions that can make entire systems more

sustainable. This approach has become known

generically as green IS or green information systems

and it incorporates not only the principles of green

information technology, which focuses largely on

data centre and hardware efficiency, but also on the

capacity of a range of digital tools, and information

itself, to enable organisations and communities to

become more sustainable. It recognises that

sustainability is a multi-faceted concept involving

economic, environmental and social contexts. While

an information technology (IT) transmits, processes,

or stores information, an information system (IS) is

an integrated and cooperating set of people,

processes, software, and information technologies to

support individual, organizational, or social goals.

The focus of this research is, therefore, on “green

IS” rather than “green IT” because green IS gives us

the potential to (i) measure and process vast amounts

of data, (ii) transform physical processes into virtual

ones and (iii) improve the efficiency of physical

processes. Though very much in its infancy, the

literature notes a role for green IS in a range of areas

including traffic management systems, virtual

presence technologies, and in supporting informed

decision making in the provision and use of services.

An increasingly important role for green IS is

highlighted in the management of supply and

demand networks. Supporting both service provision

222

Bradshaw R. and Donnellan B..

Energy Informatics Can Optimize the Design of Supply and Demand Networks.

DOI: 10.5220/0004406202220227

In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Smart Grids and Green IT Systems (SMARTGREENS-2013), pages 222-227

ISBN: 978-989-8565-55-6

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

and service usage through intelligent systems design

is an opportunity to fundamentally transform

business processes while delivering on the

economic, social and environmental imperatives of

sustainability

1.2 Energy Informatics

Energy informatics (Watson et al, 2010) is an IS

framework which specifically addresses this area.

The framework proposes an integrated approach to

the design and implementation of systems which

support energy efficiency while adopting specific

architecture and design elements. The core concept

behind the energy informatics (EI) approach is that

energy + information should result in the

consumption of less energy. As such, the framework

concerns itself with improving the efficiency of

energy demand and supply systems. The framework

aims to incorporate disciplines such as management

science, design science and policy formation in

conjunction with high granular data about the

provision and use of energy to develop systems that

can improve outcomes for the environment. The

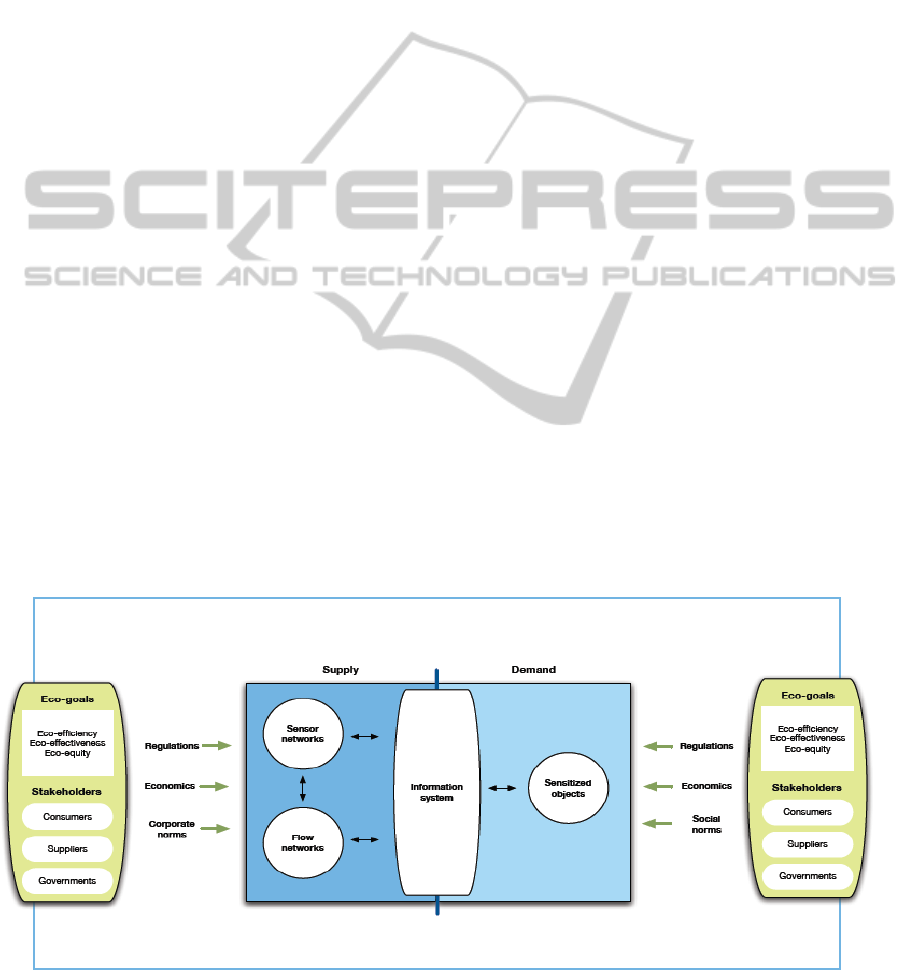

framework is illustrated below.

Suppliers can more effectively manage service

delivery if supplied with the appropriate usage

information from the consumer (Watson et al,

2009)

A flow network is a set of interconnected

transport elements that enables the movement of

continuous matter such as oil, electricity, water etc

or discrete objects such as cars, bikes, packages or

people (Watson et al, 2010). A sensor network, as

defined by the energy informatics framework, is a

set of connected, distributed devices whose purpose

is to report on the status of some physical object or

environmental condition i.e. air pollution or machine

health (Milenkovic et al, 2006). Effective sensor

networks are reliant on fine grained information. A

sensitized object is a physical item which is owned

by the energy consumer and has the ability to gather

and report data about its use. Domestic appliances

for example can be sensitized with smart plugs

which report on power usage and support smart

metering (Jahn, 2010). Of central importance to the

framework is the capacity of sensitized objects to

give the consumer the information they need to use

the object intelligently and with the environment in

mind. The role of the information system is to

integrate all the other elements of the framework to

provide a complete design. The technical elements

of the framework are augmented by integrating

social and organisational contexts, eco-goals and the

primary stakeholders in the supply and demand

network paradigm i.e. service suppliers and service

users.

Eco-goals are well documented in the

sustainability literature. Unsurprisingly, cost saving

remains high on the list of expected returns from

green IS investment. Corporations are largely

motivated to pursue eco-efficiency by the prospect

of cost reduction and it typically involves the

“efficient” use of resources in order to reduce

negative impacts on the environment (Dedrick,

2010). Eco-equity relates to the principle that all

peoples and generations should have equal rights to

environmental resources (Gray, Bebbington, 2000).

Figure 1: Energy Informatics Framework (Watson et al, 2010).

EnergyInformaticsCanOptimizetheDesignofSupplyandDemandNetworks

223

Developing these norms and ensuring that energy

sustainability is seen as an imperative will require

the active support of opinion leaders and

governments (Watson et al 2010). Eco-effectiveness

is concerned with “doing the right things” as

opposed to “doing things right”. Political leaders in

Denmark for instance have levied a 180% tax on

petrol engined cars while zero-emission vehicles are

exempt, and the New York Times (29 July, 2011)

notes that countries such as France, Germany,

Britain, Portugal and Spain all heavily subsidize the

purchase of electric vehicles (EVs). Similar

approaches are in evidence in both the US and Asia

(Ahman, 2004).

In addition Watson proposes four key design

elements. These are ubiquity, uniqueness, unison

and universality and their usefulness in the design of

information systems is well established within the IS

literature (Outram, 2010, Tzeng, 2008, Sammer,

2011, Galanxhi-Janaqi, 2004, Placido et al, 2011).

Ubiquity is access “to information unconstrained by

time and space” (Junglas, Watson, 2006). Providing

ubiquitous access to information about a service

enables users to access information from wherever

they may be located and to explore their options to

increase the usefulness of that service. Unison,

sometimes referred to as consistency, proposes that

the procedure of accessing information varies as

little as possible. This might mean that users could

access information from multiple services or

locations while needing only to learn a single

procedure. Universality relates to the drive to reduce

compatibility issues or friction between information

systems in order to achieve seamless data exchange.

XML (extensible markup language), web services,

and application programming interfaces (APIs) have

become the de facto means of achieving this

interoperability (Rainer and Cegielski, 2011, pp184).

Uniqueness is described in the literature as “knowing

precisely the characteristics and location of a

person or entity” (Junglas, Watson, 2006). With

information, it can be used to find the best match

between the user’s needs and the physical resources

available. Many bikesharing schemes for example

uniquely identify both bikes and users, which means

that users can view the availability of bikes and

parking spaces on a station by station basis while

system administrators can use usage patterns to

inform fleet management and other operational

functions (Buttner et al, 2012)

Research suggests, (Watson, 2009, Outram et al

2010, Midgely 2009, Chowdhury, 2007), that the

more successful systems have supported their

physical infrastructure with information systems

which implement these elements. They “minimise

the limitations of the physical system and enable and

support users to adopt behaviours that help rather

than hinder the environment” (Outram et al, 2010).

2 EI IN PRACTICE – THE

COPENHAGEN WHEEL

Bikeshare schemes have become an increasingly

popular phenomenon in recent years as urban

planners across the world have used them to

improve urban mobility and reduce the

environmental impact of motorised transportation

systems. The basic premise of the schemes is that

bikes are made available throughout the city

environment and are then used to support what are,

for the most part, relatively short trips. The schemes

have the added benefit of providing a link between

existing transport nodes and required destinations.

System providers include governments, public-

private partnerships, transport agencies, universities,

advertising agencies and for-profit organisations

(Midgely, 2011). Schemes typically use independent

docking stations capable of automatically checking-

out and returning bikes. Users are required to

subscribe to the schemes initially and can then

access the bikes through a variety of technologies

which include smart cards, fobs, direct access codes,

or SMS (Buttner et al, 2011). System information,

such as the availability of free bikes and stands, or

the riders’ usage statistics, is typically made

available through web based applications, or at

interfaces incorporated into the station kiosks.

Kiosks can usually support registration and payment

options. The recent adoption of mobile phone

applications by many schemes has also improved

access and usability (Buttner et al, 2011). From an

EI perspective, bikeshare schemes can be seen to

represent conventional supply and demand networks

which attempt to manage the “flow” of bikes in

order to maximise the number of trips.

The Copenhagen wheel is a research project

developed in 2009 by the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology’s SENSEable City lab for the

Kobenhavns Kommune - the Copenhagen

Municipality. Though not being developed

exclusively for the bikeshare environment, the

development team anticipate that this will be its

primary application. Through the use of mobile and

web technologies the wheel attempts to replace the

traditional kiosk and docking station model and

allow bikes to be secured to any traditional bike

SMARTGREENS2013-2ndInternationalConferenceonSmartGridsandGreenITSystems

224

rack. This stationless design requires significantly

reduced infrastructure and investment. To enhance

usability and appeal to a greater cross section of

users, the bikes are electric hybrid vehicles. The rear

wheel hub, using a Kinetic Energy Recovery System

(KERS), captures the dissipated energy from

pedalling and braking using torque sensors and

stores it until needed by the rider. The hub also

contains real-time sensing technology which can

transmit information about the environment,

personal fitness and location to an integrated

smartphone and also via the cell phone network to

the web. The sensitized object in this design is

represented by the hub.

The sensors it contains can detect CO

2

, NOx (fig

2), temperature, noise (dB) and humidity. In addition

to environmental sensing, the suite also monitors the

riders speed, relative inclination (through the use of

a gyroscope), distances travelled and so on. See

figure 3.

Figure 2: NOx data collected while cycling in Copenhagen

during December 2009 (Outram, 2010).

The system uses GPS to provide its sensor network

which supports active tracking. Route information,

plus the data generated locally by the sensor suite, is

then relayed to a central server using the cellular

network. This allows riders to review the data in

their own time using the systems’ web based

interface. Data developed over extended time

periods can also be used to support predictive and

demand modelling. In addition, the real-time

visibility of the bikes significantly reduces the

impact of theft and vandalism.

The information system in the Copenhagen

Wheel is an open, XML compliant platform and

designed with high levels of inter-operability and

universality in mind. The scheme provides social

media functionality within its site to support user

interaction and has also developed links to Facebook

and Google+. Riders see any badges or awards they

or their friends have received from the system for

achieving personal targets in relation to calories

burned or CO

2

offset etc. Using social media to

support information exchange also encourages riders

to develop relationships which can improve safety

from both physical and psychological perspectives.

In addition, the scheme recognises the importance of

incorporating external data sets which have the

potential to enhance usability and performance. An

app to incorporate real-time weather forecast data

into the existing information suite is currently being

deployed for example and the developers are also

focused on incorporating data from other transit

modes. This should enable enhanced trip planning

and customisation across public transportation

systems and/or car-to-go schemes.

Figure 3: Smartphone analyser showing environmental

and health data.

Unison or information consistency is supported by a

common system view which is provided by an

integrated database and uniqueness is enabled by

having visibility of riders throughout the entirety of

the usage period. Visibility of the bikes at all times

enables accurate systems updates to be provided to

riders and supports meaningful bike distribution by

system operators. Ubiquity is perhaps the schemes’

defining characteristic. Multiple streams of real-time

data are available to riders at all times via the

smartphone interface which mirrors the trend

towards the use of dashboard telemetry in motorised

transportation as a way of informing driver

behaviour. To avoid cognitive overload the rider can

choose to view as much or as little data as they feel

appropriate.

The Copenhagen Wheel places a high value on

reciprocal relationships, both internal and external.

Internally, the scheme encourages riders, through the

use of incentives, to add value to the data collected

EnergyInformaticsCanOptimizetheDesignofSupplyandDemandNetworks

225

through feedback and route annotation. This user

generated content can be seen as an additional

sensor network complimenting and supporting the

scheme’s sensing technologies. Externally, the

Copenhagen Wheel is focused on creating

partnerships with both local government and

independent 3

rd

parties. Through these relationships

the value of the data collected can be properly

exploited i.e. it can inform urban planning, drive

improvements in cycling infrastructure or enhance

integration with other transportation modes.

Figure 4 illustrates the Copenhagen Wheel from

an EI perspective.

Figure 4: Energy Informatics and the Copenhagen Wheel.

3 CONCLUSIONS

3.1 Addressing the Initial Position

The effectiveness of system design, i.e. the degree to

which both sides of the supply and demand

paradigm are supported, can be seen to be a function

of the characteristics of the information being

disseminated within the scheme. The variety,

reliability, timeliness and granularity of information

“sensed” by the combination of sensitized object and

sensor network, and distributed by the central

information system, have a direct bearing on the

degree of visibility providers have of system usage

which in turn impacts on a wide range of operational

and management functions. These include bike-

distribution, fleet maintenance, infrastructure

planning, and the management of threats such as

theft and vandalism. Additional information streams,

imported from the external environment have the

potential to enhance overall system performance and

improve the level of connectedness schemes have

with their environments. Providing accurate,

granular data on how riders are using the system

allows them to make informed choices about their

behaviour.

In effect, the right information can support the

dynamic adjustment of supply and demand

requirements. “Flow”, in the form of bikes and

riders, can be optimised by the use of smart

technologies and digital tools combined in an

architecture which integrates key system

stakeholders. These are the core principles of the EI

framework. The framework does not prescribe a

particular set of technologies or architectures per se

but instead proposes a set of principles by which the

potential of information can be leveraged to optimise

efficiency. It provides an understanding of the role

played by each of the components that comprise the

overall supply and demand network and provides a

blueprint for exploiting them to optimise

performance.

The contextual deminsions of energy informatics

are also supported by the case study. It demonstrates

that eco-goals, an important element in Watson’s

framework, can be major contributors to design and

performance. It illustrates for example that eco-

efficiency and eco-effectiveness need not be

mutually exclusive. On the contrary, it suggests that

the stationless design, which impacts least on its

environment and supports the greatest levels of

usability and customisation, is also the most cost

effective. In summary, improved design is achieved

by:

Allowing schemes to be understood from the

perspective of supply and demand networks.

Providing a frame of reference by which the value

of their existing information and technical

infrastructure can be understood and evaluated.

Recommending a set of informational attributes,

design elements and eco-goals which can be used

to improve performance and sustainability.

3.2 Future Research Opportunities

Useful further research would be to explore the

potential of the framework to support the design of

networks across other domains. In addition to the

transportation environment, opportunities exist for

example in areas such as the delivery of services

such as electricity, water, or gas. These

environments represent more conventional supply

and demand relationships yet the potential of

information to support both service provision and

service use in a manner similar to bikesharing is

high and the industries are influenced by regulatory

and environmental factors that also resonate with the

bikesharing domain i.e. political stakeholders,

corporate motivations and so on.

There may also be potential in exploring the

SMARTGREENS2013-2ndInternationalConferenceonSmartGridsandGreenITSystems

226

value of informational tools in increasing the

efficiency of areas such as open data platforms,

telephony or internet service provision, which again

contain the core elements of supply and demand

networks i.e. service providers, service users, and a

flow of content to be regulated. It would also be

interesting for instance to establish to what degree

collaborative relationships impact the design of

networks in these environments.

REFERENCES

Ahman, M (2004) Government policy and the

development of electric vehicles in Japan - Energy

Policy 34 (2006) 433–443 Science Direct [Accessed

11/01/2012]

Buttner, J. Peterson, T. Reth, P (2011) Optimising

Bikesharing in European Cities (OBIS): A Handbook -

http://www.obisproject.com/ - [Accessed 17/12/2011]

Chowdhury, G. (2011) Building Environmentally

Sustainable Information Services: A Green IS

Research Agenda. Journal of the American Society for

Information Science and Technology Volume 63,

Issue 4, pp 633–647 Wiley Online [Accessed

12/06/2012]

Dedrick, J. (2010) Green IS: Concepts and Issues for

Information Systems Research. Communications of

the Association for Information Systems Vol 27 No1

[Accessed 15/2/2012]

Gray, R. Bebbington, J. (2000) Environmental

Accounting, Managerialism and Sustainability: Is the

Planet Safe in the Hands of Business and Accounting?

Advances in Environmental Accounting and

Management Vol 1 No 1 pp. 1-44. Emerald Database

[Accessed 09/01/2012]

Jacobson, M (2008) Geophysical Research Letters Vol.

35, L03809, doi:10.1029/2007GL031101,

http://cleanairinitiative.org/portal/system/files/articles-

72482_full_0.pdf [Accessed 1/6/2012]

Jahn, M. Jentsch, M. Prause, C.R. Pramudianto, F. Al-

Akkad, A. Reiners, R. (2010) The Energy Aware

Smart Home - Future Information Technology

(FutureTech), 2010 5th International Conference on –

IEEEXplore Digital Library – [Accessed 4/01/2012]

Junglas, I. Watson, R. (2006) The U-constructs: Four

Information Drives. Communications of AIS 17, 569–

592. Issue 17, p2-43, 42p EBSCO [Accessed

13/01/2012]

Midgely, P (2011) Bicycle-Sharing Schemes: Enhancing

Sustainable Mobility in Urban Areas

https://www.un.org/esa/dsd/resources/res_pdfs/csd-

19/Background-Paper8-P.Midgley-Bicycle.pdf.

[Accessed 19/12/2011]

Milenkovic, A. Otto, C. Jovanov, E. (2006) Wireless

sensor Networks for Personal Health Monitoring.

Computer Communications Vol 13-14, pp 2521-2533

SciVerse database [accessed 24/06/2012]

Outram, C. Ratti, C. Biderman, A (2010) The Copenhagen

Wheel: An Innovative Electric Bicycle System that

Harnesses the Power of Real-Time Information and

Crowd Sourcing - http://cgt.columbia.edu/files/

papers/Outram_Ratti_Biderman_EVER2010_Monaco.

pdf [Accessed 14/01/2012]

Rainer, K. Cegielski, C. (2010) Introduction to

Information Systems Enabling and Transforming

Business 3

rd

Edition Wiley

Sammer, T. Carmicael, F. Andrea, B (2011) Integrating

the Smartphone: Applying the U-Constructs Approach

on the Case of University Mobile Services.

http://www.slideshare.net/thfs/mcis2011-integrating-

the-smartphone-applying-the-uconstructs-approach-

on-the-case-of-mobile-university-services [Accessed

12/05/2012]

Tzeng, S. Chen, W. Pai, F (2008) Evaluating the business

value of RFID: Evidence from Five Case Studies. Int.

J. Production Economics 112 (2008) 601–613

SciVerse database [Accessed 12/06/2012]

Watson, R Boudreau, M (2009) Energy Informatics

Driving Change Through Competitive Thought

Leadership SIM Advanced Practices Council

[Accessed 17/12/2011]

Watson, R. Boudreau, M. Chen, A. (2010) Information

Systems and Environmentally Sustainable

Development: Energy Informatics and New Directions

for the Community. MIS Quarterly Vol. 34 No 1, pp

23-38

Wood, G. Newborough, M (2002) Dynamic Energy-

Consumption Indicators for Domestic Appliances:

Environment, Behaviour and Design Energy and

Buildings, Volume 35, Issue 8, September 2003, Pages

821-841 Science Direct [2/01/2012]

EnergyInformaticsCanOptimizetheDesignofSupplyandDemandNetworks

227