Some Insights into the Role of Social Media in Political Communication

Matthias Roth

1

, Georg Peters

1,2

and Jan Seruga

2

1

Munich University of Applied Sciences, Department of Computer Science and Mathematics, Munich, Germany

2

Australian Catholic University, School of Arts and Sciences, North Sydney, Australia

Keywords:

Microblogging, Politics, Social Media, Twitter.

Abstract:

Political communication in the social media network of Twitter has enjoyed a popularity increase in recent

years. This also meant that the microblogging platform Twitter is now used in different countries for political

campaigns as well as political discussions. For this study we collected data from more than 1,400 politicians in

three countries Australia, Germany and the U.S. through the Twitter API. This data set with nearly one million

tweets is the basis for our analyses, where we compare the behavior of the politicians on Twitter regarding

differences and similarities in the political context. Amongst others we compare key figures concerning the

year of joining, age groups, gender, user activity, and trend topics in the named parliaments. Thus we gain

insight into the political communication on Twitter in the mentioned countries.

1 INTRODUCTION

Social media using Web 2.0 technology has emerged

over the past few years as space for online commu-

nication. Meanwhile different services like Wikis,

Blogs and Social Networks provide the opportunity

for people to get together online. In addition it is pos-

sible to consume content and also publish your own

content. Furthermore, social media caused a change

in the traditional structure of mass communication in

the political context. Besides newspapers, magazines

and TV channels a lot of political communicationnow

goes through these Social Media Platforms. These al-

low a straight forward communication between politi-

cians and citizens who are interested in politics.

Based on the U.S. Congress, the development of

political participation in social media can be traced.

It was observed that more than 65% of members of

the U.S. Congress had established a personal web site

by 1997 (Adler, 1998). Also in 2005 it was inves-

tigated that nearly all members of the U.S. Congress

had developedweb sites (Esterling et al., 2005). In the

near past, February 2009, two months after the 2008

election 69 Congress members (which was a share of

about 13% of the U.S. Congress) maintained a Twit-

ter account (Golbeck et al., 2010). Just after the 2012

election the share was about 91%. These increased

figures show that the political communication in the

U.S. has evolved in the direction of social media.

With interfaces that allow people to follow the

lives of friends, acquaintances, and families, the num-

ber of people on social networks has grown expo-

nentially in recent years. Facebook, Twitter and

LinkedIn, to give a few examples, contain hundreds

of millions of members, who use these networks for

keeping track of each other. In 2004, Mark Zucker-

berg created Facebook as a way to connect with fel-

low students. Now, in October of 2012 Facebook

has about one billion monthly active users (Facebook,

2012).

Another example: Twitter, launched in July 2006,

is an online social networking and microblogging ser-

vice that has about 500 million accounts (Semiocast,

2012). Also LinkedIn is a social networking web

site for people in professional occupations and was

launched in 2003. With more than 180 million mem-

bers in over 200 countries LinkedIn is the largest

professional network in the world (Morphy, 2012).

According to the user base of these three platforms

also the site visits rose sharply. Alexa, a company

that tracks web traffic, ranked Facebook, Twitter and

LinkedIn as three of the most visited sites in the

world. Currently, Facebook is in this ranking on po-

sition two just behind Google. The web sites Twitter

and LinkedIn follow with the rankings of eight and

thirteen (Alexa, 2012). This shows that social media

is more and more spread.

In this paper, we contribute to the research field

of social media in politics by examining the relevance

of Twitter in political communication by the exposi-

351

Roth M., Peters G. and Seruga J..

Some Insights into the Role of Social Media in Political Communication.

DOI: 10.5220/0004418603510360

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 351-360

ISBN: 978-989-8565-60-0

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

tion of Twitter activities in politics for three differ-

ent countries. More specifically, we explore the ac-

tivity of using social media in general and compare

the single parliaments of Australia, Germany and the

U.S. regarding activity, contribution in online politi-

cal communication and further statistical figures.

Based on our findings, we derive implications, re-

garding politics in the named countries. Additionally,

we provide a section related work for the fields of po-

litical science and social media.

This paper is structured as follows. The next sec-

tion provides related work on political science and so-

cial media. Also you can find information about the

methodology and research questions in section two.

Furthermore, in our main part we present our research

findings in sections three and four. The paper ends

with an conclusion and gives an outlook for future re-

search.

2 RELATED WORK AND

METHODOLOGY

Twitter is a digital realtime Application for the dis-

tribution of short messages. It is also described as a

communication platform for social networking or as

a public online log. Private persons, enterprises, mass

media and also politicians use the platform for distri-

bution of short messages. On this basis we provide in

this section related work about political science and

social media and especially Twitter. In addition to the

related work this section contains a description about

the used methodology.

2.1 RELATED WORK

There has been some prior work on analysing social

media. As a basis for further investigations there

are works about social networks like the book by

Wasserman and Faust, which describes different mod-

els, methods and applications for analysing social net-

works (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). Also much re-

search is available about social science topics, which

focus on the subjects of measuring performance of in-

dividuals and collectives to networks of social rela-

tionships. Backstrom, for example investigated group

formations like membership, growth and evolution in

large scale networks (Backstrom et al., 2006).

In terms of political communication Golbeck et al.

present in their study a framework for viewing or un-

derstanding the content of Congressional communi-

cation through the capturing and categorizing of in-

dividual messages (Golbeck et al., 2010). Java et al.

identified different types of user intentions and stud-

ied community structures also with respect to politics

(Java et al., 2007).

In this elaboration, the focus is on Australia, Ger-

many and the U.S. For these three countries initial

studies have already been conducted with regards to

political discussion on Twitter. For example Missing-

ham looked at the Australian parliament in the Twit-

terverse (Missingham, 2010). Missingham found in

her 2010 study that the Australian parliament was ex-

ploring the use of Twitter and about 15% of the Aus-

tralian parliament members had a Twitter account.

For the German parliament Tumasjan tried to in-

vestigate in an analysis of the 2009 election whether

Twitter is used as a platform for political communi-

cation and in addition whether Twitter can be seen as

a valid mirror for offline political sentiment (Tumas-

jan et al., 2010). Regarding the U.S. Smith shows,

how Barack Obama has used social media in the 2008

election campaign and the following use of social me-

dia in political campaigns in the U.S. (Smith, 2011).

2.2 Methodology

This paper aims to understand how members of a par-

liament communicatethrough Twitter. When and how

often they tweet, howmany followers and friends they

have and how often their tweets are being retweeted.

In addition to the named figures, a comparison be-

tween the parliaments of Australia, Germany and the

U.S. is made. Thereby the focus is on the flow of

communication from the government to the public.

For example all the tweets and followers of various

politicians will be examined but not the comments

and communication from public to the government.

As such, we have collected and analysed information

about Twitter accounts and single posts. In this sec-

tion, we will describe the data collection and research

questions.

2.2.1 Data Collection

First of all, information about the Members of the Par-

liaments like forename, surname, age, party affiliation

and Twitter account names were obtained by the cor-

responding web sites of the Australian, German and

U.S. parliament. Thus we have acquired data for dif-

ferent houses. Our data consisted of a Senate and a

House of Representatives each for Australia and the

U.S., whereas for Germany, we used the comparable

Bundestag and Bundesrat.

In Table 1, we show the different houses for Aus-

tralia, Germany and the U.S. together with the corre-

sponding seats. The House of Representatives is also

called the Lower House or Bundestag in Germanyand

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

352

represents the people. The Senate or Upper House

in Germany is called Bundesrat and is established for

representing the single states of a country.

Therefore, difference between the Senate and

House of Representatives is less conceived as repre-

sentation of the total number of the states people, as

more than representation of the states at the federal

level. For easy intelligibility we will speak about par-

liaments and parliament members or parliamentarians

for all three countries.

Table 1: Houses and seats of the parliaments.

Australia Germany U.S.

Lower

House

House of

Represen-

tatives

Bundestag House of

Represen-

tatives

Seats 150 620 435

Upper

House

Senate Bundesrat Senate

Seats 76 69 100

For subsequent collection of Twitter data a Java

application was developed which makes use of the

Twitter Application Programming Interface (API)

(Twitter, 2012). Over this interface information like

Twitter account data and tweets can be accessed.

Through the development of further analysis capabil-

ities for our application we could gain more informa-

tion from the downloaded data. Among others we

have developed functions to identify trending topics,

calculate the activity status and get the quantity of

mentions of an account in the corresponding parlia-

ment. All these information serve as the database for

research.

• Users. We only have added accounts to our data

set for which a profile picture existed, because

only then real interest for social media is iden-

tified. Furthermore there are a lot of fake ac-

counts for politicians. There are currently more

than 20 fake accounts for the former Australian

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

Some of the fake accounts clearly labeled as fakes

and some are not so easy to recognize as fakes.

Most easily this can be handled by Twitter verified

accounts, but not many politicians have verified

accounts.

So we found the proper accounts by visiting

politicians web sites. It is further pointed out that

many accounts are not maintained by the politi-

cians themselves, but by their staff. In our study

we have all accounts treated the same, whether led

by a politician themself or even led by their team.

• Active Users. We have added all the politicians

and fetched their data, but the variable indicating

whether each Member of the Parliament has cre-

ated a Twitter account is not convincing. Not all

Members of the Parliament continue using their

Twitter account after creating it. For example, 109

Australian (48%), 283 German (41%) and 489

member of the U.S. parliament (91%) created al-

ready a Twitter account, but overall there are still

13 accounts with not a single tweet. Therefore,

we use an additional measure named active user

in an effort to account for these differences. Here

we determine that an active user has on average

two or more tweets per week posted.

As shown in Table 2 this results in 74 Australian,

168 German and 393 active users in the U.S. The

table furthermore shows the indicators regarding

tweets, followers and friends for our data set di-

vided into three countries of investigation. These

three indicators relate to the total number of ac-

counts, not just the active users.

Table 2: Indicators of the data set.

Australia Germany U.S.

Members 226 689 535

Accounts 109 283 489

Active Users 74 168 393

Tweets 117,121 291,671 482,945

Followers 2.3 M 0.5 M 32.7 M

Friends 720,929 105,144 1,369,424

2.2.2 Research Questions

In this paper, we answer different questions regarding

the social media behavior of politicians. Therefore,

we have gathered data, as described. We use these

to generate information out of the demographic data,

like gender and age group. Furthermore, we compute

analyses regarding the Twitter data like the numbers

of tweets, followers and friends. Subsequently we use

the language and environment R for statistical com-

puting and graphics to analyse the data regarding our

research topics (Gentleman and Ihaka, 2013).

In the next section we will present our findings.

Afterwards we present in another section more anal-

yses about social media on Twitter. In this part we

show summary findings regarding our data set.

SomeInsightsintotheRoleofSocialMediainPoliticalCommunication

353

Amongst others we have there analyses about the year

of joining and a summary about the complete data set.

3 FINDINGS

This is one of two main parts of our studies, where

we will present the results of our statistical calcula-

tions. Therefore, we extract relevant data for each

analysis from our database and calculate figures re-

garding gender, age groups, tweets, followers, friends

and the moving average and trend of tweets. Subse-

quently, we present our results in tables and figures.

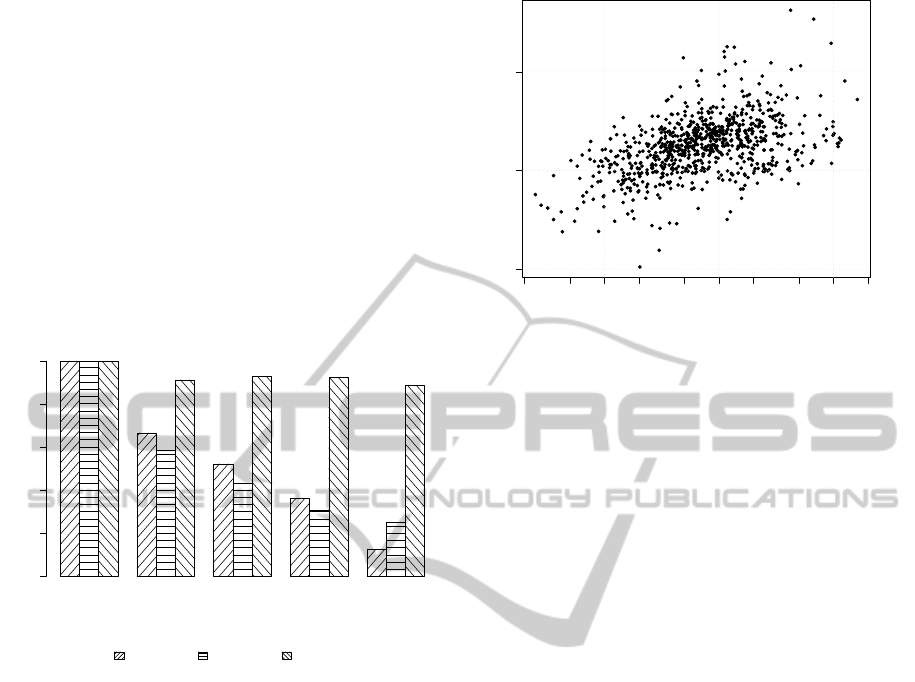

3.1 Gender

In this subsection we want to find a relation between

gender and the number of Twitter accounts among

the parliamentarians. An exhaustive study of Twit-

ter users across the world showed that more women

(53%) than men (47%) are active on Twitter (Udani,

2012). Therefore, we assume a similar picture for

politicians. In the following Figure 1 we present our

findings. These figures show that in all parliaments

the share of women with a Twitter account is larger

then the share of men. We recognized that the num-

ber of male and female accounts in each country is

close, but if we compare the countries we see signif-

icant differences, especially when compared with the

U.S.

AUS GER US AUS GER US

Gender

Percent of Parliamentarians

0 20 40 60 80 100

male

45.63%

40.00%

90.50%

female

54.55%

43.30%

94.68%

Australia Germany U.S.

Figure 1: Accounts spread across gender.

For our statistical analysis regarding the gender

we used the Pearson’s Chi-squared test with Yates’

continuity correction and got the results in Table 3.

Thereby following null hypothesis was accepted: Be-

tween men and women, there is no significant differ-

ence, regarding the number of Twitter accounts. If we

put the p-values our significance level α = 0.05, we

can see there is no significant p-value and therefore

we can not reject our hypothesis. The Phi-coefficient

in Table 3 shows us the strength of an relation. In our

case we can see a relationship between gender and the

number of accounts, but it is only a weak relation.

Table 3: Results for the statistical analysis regarding the

gender and accounts.

Australia Germany U.S.

x-Squared 1.1533 0.552 1.2129

df 1 1 1

p-Value 0.2829 0.4575 0.2707

Phi-Coefficient 0.08 0.03 0.06

The second hypothesis we test for the gender is

that the number of followers is related to the gender

and the female politicians have more followers than

male. So we use the t-test and compare the mean val-

ues of the male and female Twitter users of the in-

dividual parliaments. As null hypothesis, we assume

that the mean values are equal. Our results in Table

4 show that there are no significant p-values for our

α = 0.05. Therefore, we must assume that there is

no relation between the number of followers, and the

gender.

Table 4: Results for the statistical analysis regarding the

gender and followers.

Australia Germany U.S.

Sum Men 1823354 371768 31394863

Sum Women 489467 179287 1279302

Mean Men 24977 1998 78487

Mean Women 13596 1848 14374

t 0.6142 0.3135 1.0107

df 102.87 200.447 402.011

p-Value 0.5405 0.7542 0.3127

Conf. Inter. -25372 -795 -60586

Conf. Inter. 48134 1096 188812

3.2 Age Groups

In Figure 2 we can see an analysis of our data with

respect to individual age groups. We expect that the

younger generations are more represented on Twitter

than the older ones, as younger generations adopt new

technologies like Twitter faster than older. In addition

to this outcome it also turns out, as already in the last

section about gender, that far more politicians in the

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

354

U.S. are present on Twitter. In comparison to Aus-

tralia and Germany, this is particularly the case in the

age groups over 35 years.

In Figure 2 we can see, while in the first age group

<34 all three countries have an identical rate of 100%.

In Australia and Germany the rate declines in the fol-

lowing age groups. However, in the U.S. the rate al-

ways remains well above 80%. In the U.S. Twitter

plays a major role over all age groups, while the par-

ticipation in Australia and Germany decreases with

the age. With increasing age, this distance between

the U.S. on the one hand and Australia and Germany

on the other hand increases. This shows that there is

a great catch-up in older politicians in the countries

Australia and Germany.

< 35 35 − 44 45 − 54 55 − 64 > 64

Age Groups

Accounts in percent

0 20 40 60 80 100

Australia Germany U.S.

Figure 2: Accounts spread across age groups.

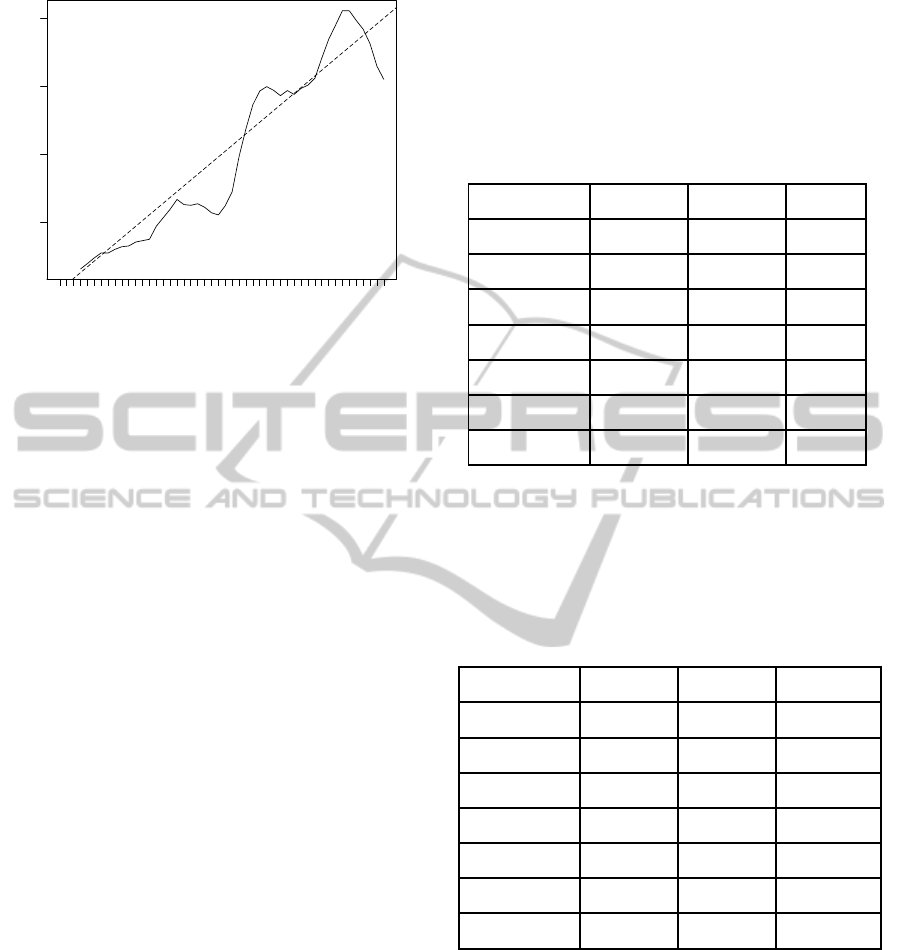

3.3 Tweets & Followers & Friends

In this section we compute the correlations for the

variables tweets, followers and friends and present the

results in scatter plots. A scatter plot displays the di-

rection and strength of the linear relationship between

two variables and therefore it is well suited.

First, we calculated the correlation and found

a slight correlation of 0.16 between followers and

tweets, even if our p-value indicates a statistically sig-

nificant value, we can not assume at this low correla-

tion that a politician can enlarge the number of his

followers by publishing more tweets. We present the

resulting scatter plot in Figure 3.

Second, as we have further assumed, there is a

correlation between friends and followers. The Cor-

relation Coefficient (cor) has a value 0.53 and it is

thus worth to be classified as a medium correlation.

This shows that politicians can increase their reach by

adding more friends to their profile as this leads to an

increase of followers.

Finally, we calculated the Correlation Coefficient

(cor) for the variables friends and tweets. There we

20 50 100 500 2000 5000 20000

1e+01 1e+03 1e+05

Tweets

Followers

Figure 3: Correlation between followers and tweets.

can also find only a slight value of 0.14. It reveals that

the number of friends a politician has, is not related to

the number of tweets and therefore a politician who

tweets frequently does not necessarily add regularly

friends to his network.

Our results in this section show, therefore, that

politicians, especially when they actively invite

friends in their network can achieve a greater scope.

This is the case, as the addition of new friends in-

creases the number of followers as we found through

the calculation of the correlations.

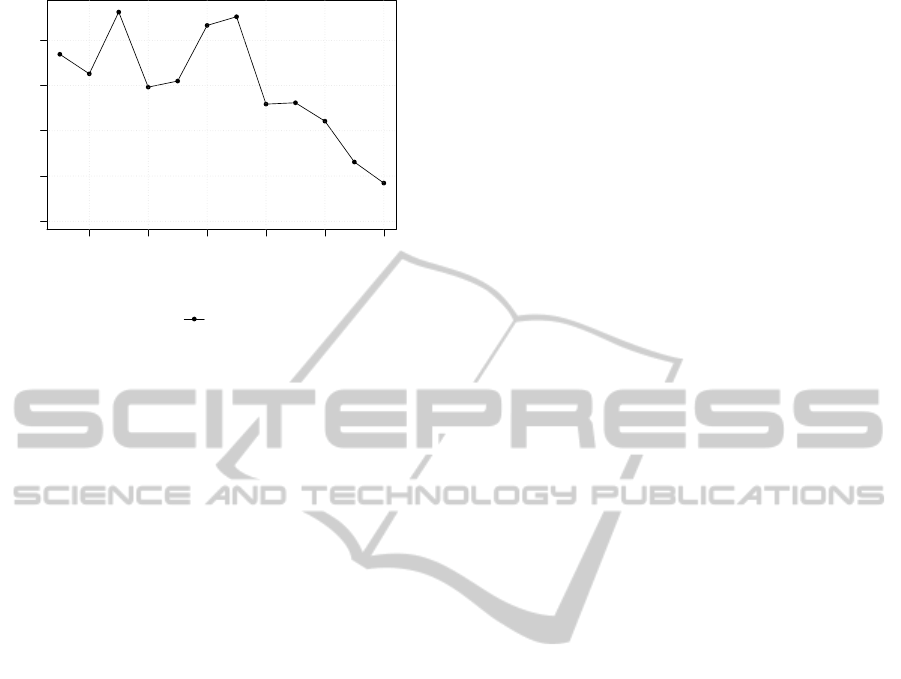

3.4 Tweets Moving Average and Trend

In Figure 4 we show the simple moving average

(SMA) and the trend for the U.S. parliament regarding

the average of tweets. Thus we reveal, how the use of

Twitter among parliamentarians has developed. The

goal is to check whether a trend is present in the time

series or not. For our calculations we used for each

parliament the dates of the entire years from 2009

to 2012. The computations furthermore assume that

the observations are independent. Since the gradients

of the individual countries are comparable, we show

only the U.S. figure as an example.

For Australia the figures show that for every turn

of the year the SMA line has a deep, which means,

that the politicians tweet less in this time. Nonethe-

less, we see a strong increase of the number of tweets

during the investigated years from 2009 to 2012. At

the end of the graph we see again that the number of

tweets at year-end decreases in Australian parliament.

For the German figures we see the phenomenon

for Australian turn of the year only from year 2009

to year 2010. Otherwise, the number of tweets in-

creases during the relevant period. At the beginning

less strongly but from mid-2011, we see a very strong

SomeInsightsintotheRoleofSocialMediainPoliticalCommunication

355

5000 10000 15000 20000

Observed Month

Average Tweets

Jan 09 Sep 09 Mai 10 Jan 11 Sep 11 Mai 12

Figure 4: Moving average and trend for the number of

tweets in the U.S.

increase, which only will weaken slightly at the end

of the year 2012.

Finally, we have the SMA and trend for the num-

ber of tweets in the U.S. in Figure 4. Here we can see

again at the turn of the years 10/11 and 11/12 there is

a decrease in the number of tweets. In the U.S. there is

a strong increase in the number of tweets in the same

period. However, in 2012 the number of tweets has

fallen steadily since mid-year, what can be observed

in the corresponding period at the slope of the graph.

4 SUMMARY FINDINGS

This is the second part of our findings, where we

present summary results. In addition to examination

of our entire data set we investigate the year of joining

and trending topics.

4.1 Data Summary

In this subsection we show some descriptive analyses

for our complete data set. Therefore, we present for

each parliament the classical five-number summary

(sample minimum, first quartile, median, third quar-

tile, sample maximum) together with the mean and

standard deviation (σ), which are normally no part of

the five-number summary. These figures are used be-

cause they provide a concise summary of the distri-

bution and also point out the center and spread of it.

This makes it possible to compare quickly the result-

ing numbers of our observations.

Table 5 shows the summary regarding the number

of tweets. At minimum we can recognize that in each

parliament there are politicians, which have a Twit-

ter account but never posted a tweet. Furthermore for

Germany we can see the largest mean and 3rd quar-

tile, which leads to the conclusion that Germany has

compared to the other countries the most active quar-

ter of politicians on Twitter. The standard deviation

shows in the U.S., the number of tweets seen from the

parliament deviates the least from the mean values.

Table 5: Summary statistics regarding tweets.

Australia Germany U.S.

Minimum 0 0 0

1st Quartile 218 146 369

Median 576 440 694

Mean 1,348 1,390 1,060

3rd Quartile 1,631 1,728 1,289

Maximum 11,620 16,650 12,900

Stand. Dev. 2,048 2,303 1,309

Now we look at the following summary in Table 6.

Germany compared to Australia and the U.S. has by

far the lowest follower numbers. However, the U.S.

has by far the biggest follower numbers. Based on the

mean values it is well to assess in which category the

individual countries are classified.

Table 6: Summary statistics regarding followers.

Australia Germany U.S.

Minimum 57 0 0

1st Quartile 1,491 457 2,518

Median 3,201 977 4,664

Mean 21,220 1,947 66,820

3rd Quartile 6,274 1,656 8,185

Maximum 1.2 Mio. 32,440 25.3 Mio.

Stand. Dev. 117,388 3,865 1,145,331

Table 7 shows a similar picture for the friends as

we have already seen in the followers. Germany has

by far the lowest and U.S. by far the most friends.

Australia is again between the two countries. This

suggests that there is a dependence between the fol-

lowers and friends. This conjecture, we already ex-

amined in more detail with our statistical findings in

the section about the correlations between tweets and

followers and friends.

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

356

Table 7: Summary statistics regarding friends.

Australia Germany U.S.

Minimum 0 0 0

1st Quartile 159 55 123

Median 442 146 359

Mean 6,614 371 2,800

3rd Quartile 986 359 1,114

Maximum 369,800 12,560 667,800

Stand. Dev. 40,258 909 30,329

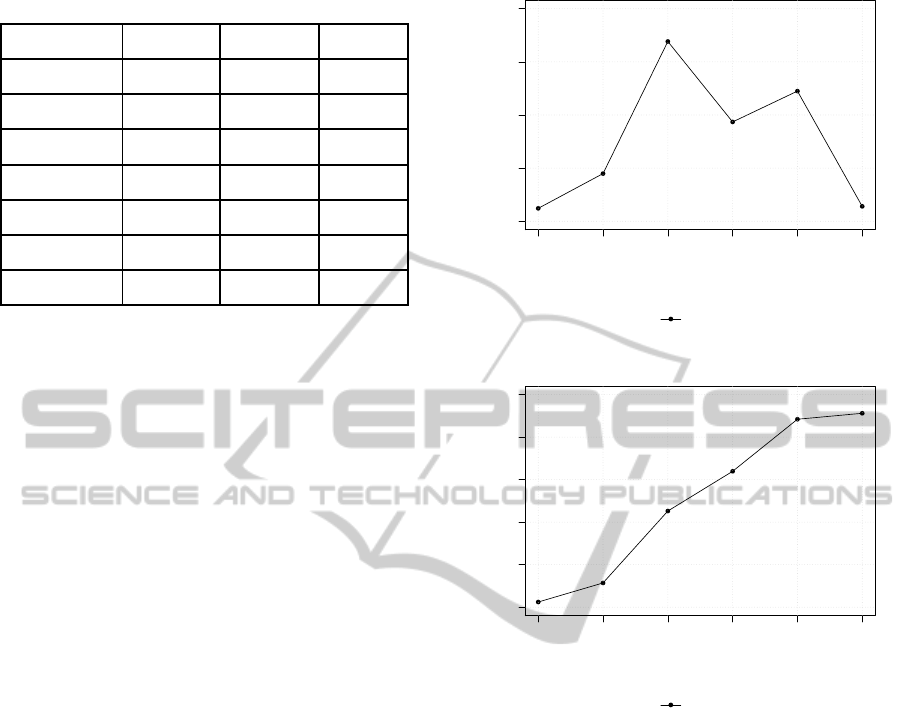

4.2 Year of Joining

From Cheng et al. we know that the big hype of Twit-

ter was in 2009 (Cheng et al., 2009). We assume that

this also applies for politicians, and compared to other

years, most of the investigated politicians have their

Twitter account created in 2009. We will check this

to see whether the number of politicians in the year

2009 actually is the highest, or whether the number is

maybe bigger in an election year. To determine how

the proliferation of Twitter has evolved in the polit-

ical landscape over the years, we have analysed the

data collected to that effect.

Twitter was launched in 2006 and the first politi-

cian of the current parliaments have created their ac-

counts in 2007. In Australia and Germany this was

one politician in each country, whereas in the U.S. 14

politicians created their Twitter account in 2007.

In Figure 5 we can see that in the U.S. 2009 was

the peak of the Twitter hype. Also we can see in

our data that, although in this year in Germany was

the Federal Election, the percentage of new arrivals in

both countries are almost on par with 23.45% in Aus-

tralia and 23.06% in Germany. In the U.S. the share

with 33.83% is even bigger.

If we look at the already shown figures in a cu-

mulative shape, we can see that the number of Twitter

joining politicians is the highest in the U.S. over all

three years. Our data set also shows that, altogether

the share of politicians with a Twitter account in Aus-

tralia with 48.23% is higher than in Germany with

41.07%. Nevertheless the largest share of Twitter ac-

counts in the parliament has the U.S. with 91.40%.

Such a high percentage of politicians with a Twitter

account in the U.S. shows that social media is ac-

cepted as a medium for sharing political information

in this country. In Australia and Germany, this is not

seen to such an extent. In Figure 6 we show the fig-

ures for the U.S. as an example.

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

0 10 20 30 40

Years

Percent of Joining

U.S.

Figure 5: Year of joining per cent.

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

0 20 40 60 80 100

Years

Percent of Joining Cumulative

U.S.

Figure 6: Year of joining cumulative.

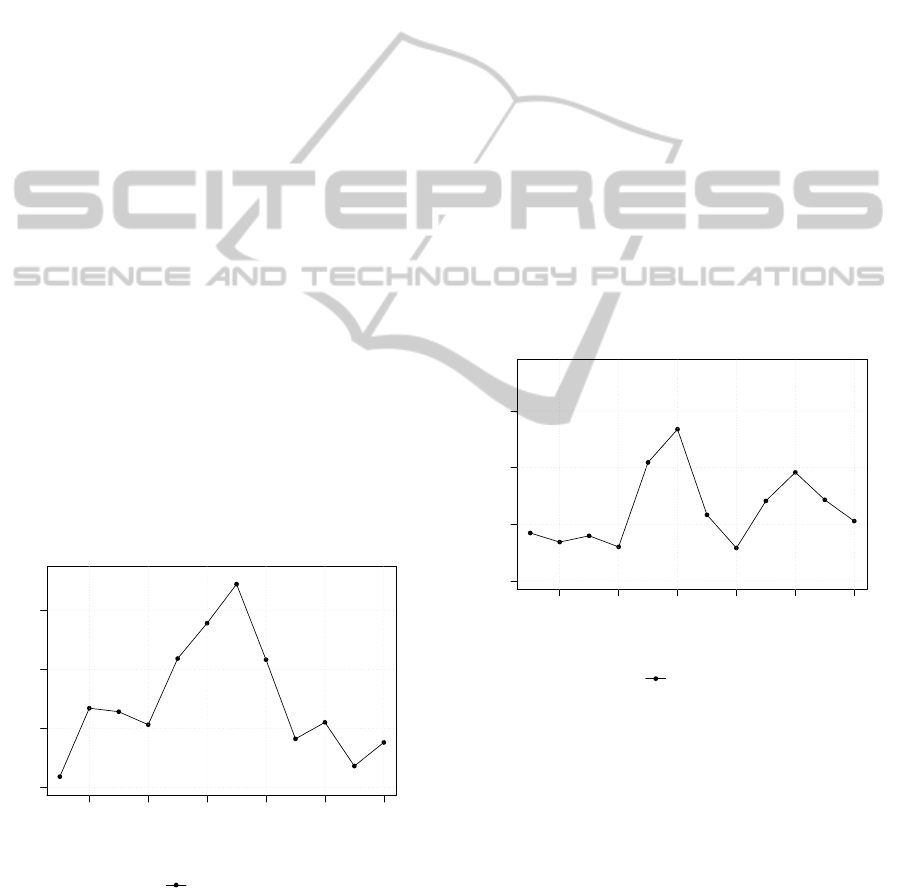

4.3 Trending Topics

In addition to the previously described indicators of

our data set, we have also examined the trending top-

ics in each parliament during the year 2012. Here we

have analysed all the tweets from our possession in

2012.

After we excluded filler words, like is, the and oth-

ers, we took the three mostly mentioned words for

each country. They are ordered by their frequency for

• Australia

1. Carbon tax

2. Health

3. Economy

• Germany

1. Europa

2. Fiskalpakt

3. Griechenland

SomeInsightsintotheRoleofSocialMediainPoliticalCommunication

357

• U.S.

1. Job

2. Tax

3. Health

Then we have considered the individual tweets to

the respective topics in more detail in order to get an

idea for what the discussion was.

4.3.1 Australian Trending Topics

As already mentioned the most trending topics in

Australia were the carbon tax, health and furthermore

the economy. When we look at the line of carbon

tax in Figure 7, we see a rise in the mid of the year

2012, with a peak in July. This we can justify by the

fact, that the carbon pricing scheme for business was

introduced in Australia by the Gillard government at

the 1st July 2012. During the text analysis of single

tweets with respect to the keyword health, we found

that in this context also often the following keywords

are used: Denticare, Medicare and Private Health In-

surance.

Our data set shows a continuous discussion on

these different health topics. Regarding the economic

topic we can give two different reasons for the on-

going discussion. For one thing, Moody’s have reaf-

firmed in May the AAA credit rating of Australia,

due to a strong economy and strong public finances.

Therefore, we see an increase in May and June for the

economic topic. On the other hand in the parliament

was regularly praised the low unemployment rate, low

inflation, low interest rates and the economy growing

trend.

2 4 6 8 10 12

0 50 100 150

Month in 2012

Number of Tweets

Carbon tax

Figure 7: Trending topics in Australia.

4.3.2 German Trending Topics

The most mentions of the German parliament in 2012

had the topic Europe (German: “Europa”) as we can

see in Figure 8. Followed by the topics European

Fiscal Compact (German: “Fiskalpakt”) and Greece

(German: “Griechenland”). For the keyword Europe

the peak in June and the previous rise was created by

a lively discussion about the Euro Crisis, the Europe

politics and the commercial policy altogether. Also

we can see a rise in September and October. The rea-

son for that is the award of Nobel Peace Prize to the

European Union.

The European Fiscal Compact sets for the Euro-

pean countries a debt limit in relation to the Gross

Domestic Product (GDP). Furthermore this compact

sets an upper limit for the annual new debt also in

relation to the GDP and establishes penalties for non-

compliance with these two limits. In Germany, the

compact on 29th June 2012 entered into force, which

leads to the peak in June. The last we have seen of

Germany was the catchphrase Greece.

Here we see two rises. One in February and an-

other in November of 2012. This is the case, as was

voted in these two months each on a bail-out package

for Greece in the German parliament. In February

was voted for the bail-out package number two and in

November for number three.

2 4 6 8 10 12

0 200 400 600

Month in 2012

Number of Tweets

Europa

Figure 8: Trending topics in Germany.

4.3.3 American Trending Topics

Australia and Germany have shown that the trending

topics especially in the middle of the year reach max-

imum values. But for the U.S. we can see in Figure 9

the mostly mentioned topic about jobs has already in

March the highest value. But also in June and July the

topic reaches high values. According to our data the

reason for that are good job growth figures which are

published in these months. The mentions of the tax

topic are high, as regularly about the achievements of

Obama tax cuts.

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

358

2 4 6 8 10 12

0 500 1000 1500 2000

Month in 2012

Number of Tweets

Job

Figure 9: Trending topics in the U.S.

Also frequently was discussed about the tax plans

of Obama and Romney after the 2012 elections. The

last U.S. topic is health, and here especially the Pa-

tient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)

which is commonly called Obamacare or the Federal

Health Care Law. It was signed into law by President

Barack Obama on 23rd Mach 2010, but PPACA con-

tains provisions that became effective after enactment

and therefore there is still a regular discussion about

this topic in the U.S. parliament.

Overall we have seen for Australia and the U.S.

that the three most important issues are about eco-

nomic (jobs, taxes) and health topics. For Germany,

however, we see that the three main topics revolve

mainly around Europe.

5 CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE

WORK

This paper focuses on social media in politics and

therefore especially on the Twitter platform and the

parliaments of Australia, Germany and the U.S.

Firstly, this paper provides an introduction to the topic

of social media in politics including Twitter followed

by other related work. Secondly, we describe the

used methodology for our studies with data collec-

tion and our research questions. Then we provide the

key findings of our investigations, based on statistical

results. Here we found that the investigated politi-

cians in each country showed a growing interest in

social media. This we were able to see, because of

the growing number of Twitter accounts registered by

the politicians and also by the increasing number of

tweets posted by the politicians. We have also found

that politicians use Twitter not only for political cam-

paigns but also for daily political discussions. Still

we have learned much about trending topics in par-

liaments. About which topics were most discussed in

the parliaments and also about the lifetime of topics

in the investigated parliaments.

Regarding the topic of social media in politics the

contributions of this paper are as follows. Overall we

provide insight into the topic of social media in poli-

tics with a focus on Twitter. We did not focus only on

the U.S. as in previous studies, but always conducted

the comparison with Australia and Germany. Next

to an insight into the subject, the results also provide

suggestions for dealing with social media in the polit-

ical context.

Our results provide an insight into social media in

politics with Twitter, but it will be important in fu-

ture research to address more social media platforms.

Especially the frequently used platforms in politics

of Facebook and YouTube should be investigated in

more detail. Furthermore, the individual websites or

blogs of politicians could be investigated or even tra-

ditional media like newspapers, magazines and TV

channels. This would provide a more detailed picture

of this topic. Also other countries could be added to

obtain more comprehensive results.

REFERENCES

Adler, Gent, O. (1998). The home style hompage: Legisla-

tor use of the world wide web for constituency contact.

Legislative Studies Quarterly, 23:585–595.

Alexa (2012). Alexa - The Web Information Company.

http://www.alexa.com/.

Backstrom, L., Huttenlocher, D., Kleinberg, J., and Lan,

X. (2006). Group formation in large social networks:

membership, growth, and evolution. In Proceedings

of the 12th ACM SIGKDD international conference

on Knowledge discovery and data mining, KDD ’06,

pages 44–54, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

Cheng, A., Evans, M., and Singh, H. (2009). Inside Twitter:

An in-depth look inside the Twitter world.

Esterling, K., Lazer, D., and Neblo, M. (2005). Home

(page) style: House members on the web. In DG.O.

Facebook (2012). Facebook - Key Facts. http://

newsroom.fb.com/content/default.aspx.

Gentleman, R. and Ihaka, R. (2013). The R project for sta-

tistical computing. http://www.r-project.org/.

Golbeck, J., Grimes, J. M., and Rogers, A. (2010). Twitter

use by the U.S. Congress. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Tech-

nol., 61(8):1612–1621.

Java, A., Song, X., Finin, T., and Tseng, B. (2007). Why

we twitter: Understanding microblogging usage and

communities. In Proceedings of the 9th WebKDD

and 1st SNA-KDD 2007 workshop on Web mining and

social network analysis, WebKDD/SNA-KDD ’07,

pages 56–65, New York, NY, USA. ACM.

SomeInsightsintotheRoleofSocialMediainPoliticalCommunication

359

Missingham, R. (2010). The Australian parliament in the

Twitterverse.

Morphy, E. (2012). Twitter to reach 500M registered users

on Wednesday. Just another day in the life of the

social media fun house. http://www.forbes.com/sites/

erikamorphy/2012/02/21/twitter-to-reach-500m-

registered-users-on-wednesday-just-another-day-in-

the-life-of-the-social-media-fun-house/.

Semiocast (2012). Twitter reaches half a billion ac-

counts - More than 140 millions in the U.S. http://

semiocast.com/publications/2012

07 30 Twitter

reaches half a billion accounts 140m in the US.

Smith, K. N. (2011). Social Media and Political Campaigns.

Tumasjan, A., Sprenger, T. O., Sandner, P. G., and Welpe,

I. M. (2010). Predicting elections with Twitter: What

140 characters reveal about political sentiment. In

Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Confer-

ence on Weblogs and Social Media, pages 178–185.

Twitter (2012). Twitter API Documentation. https://

dev.twitter.com/.

Udani, G. (2012). An exhaustive study of Twitter

users across the world. http://www.beevolve.com/

twitter-statistics/.

Wasserman, S. and Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analy-

sis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge University

Press.

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

360