Perspectives on using Actor-Network Theory and Organizational

Semiotics to Address Organizational Evolution

Alysson Bolognesi Prado and Maria Cecilia Calani Baranauskas

Institute of Computing, StateUniversity of Campinas, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

Keywords: Organizational Semiotics, Actor-Network Theory, Organizational Evolution, Norms.

Abstract: Systems design for a changing organization has long been in the research agenda of several academic and

industrial communities, and still is an open problem. This paper draws on Organizational Semiotics and

Actor Network Theory to delineate a method for clarifying and representing the social forces involved in

organizational changes. A case study illustrates the approach in which all actors – people, technical devices

and other objects –are modelled in the social level, tracing back the norms flow, their sources, enabling to

negotiate the change with the appropriate stakeholders.

1 INTRODUCTION

Enterprises and organizations are always subject to

internal and external pressure for change. Market

and politics from one side, and managerial decisions

and personal preferences from the other make the

propagation of novelties and collective evolution a

non-linear process, with forces acting in several

directions. The pervasive adoption of an always-

evolving Information Technology brings more

complexity to the scenario.

Organizational Semiotics – OS for short –

describes an organization as a “structure of social

norms, which allows a group of people to act

together in a coordinated way for certain purposes”

(Liu 2000, p. 109). The OS seeks for the cognitive

and behavioral universals of the participants of the

organization to a better understanding of the

environment in which an information system will be

deployed and run.

However, when studying the readiness of an

enterprise for the adoption of new technology, this

theory may not cover factors such as support to

managers and business process (Jacobs and Nakata,

2012). Some organizational researchers (Jacobides

and Winter, 2012; Holt et al., 2007) argue that

collective phenomena are not defined by previous

structure but instead are the result of reciprocal

actuation between individuals.

Actor-Network Theory – or ANT – claims that

social is not a specific domain of reality or some

particular attribute of people, but rather is the name

of “a movement, a displacement, a transformation, a

translation, an enrollment” (Latour, 2005, p. 64)

that occurs involving the stakeholders, their interests

and the means used to achieve them. This dynamic

point of view contributes to understand situations in

which the state of affairs is not well stabilized and

social structure is being reconfigured.

The potential of using ANT and OS together

have been already pointed out by Soares and Sousa

(2004) aiming at balancing social and engineering

approaches to introduce technology in organizations,

and explored by Underwood (2001) to understand

the diffusion of shared meanings, a prerequisite to

the success of Information Systems. These trials

provide good examples of positive aspects of

merging both theories and encourage the expansion

to address social, pragmatic and normative issues.

This paper proposes a method to trace back the

social forces involved in organizational changes. By

unveiling the network of interferences and

mediations present in a social scenario and locating

the sources of conflicting interests, it is possible to

drive the actions needed to improve the

organizational structure.

In the following sections we present

Organizational Semiotics and Actor-Network

Theory and discuss how they can complete each

other to be used as support for understanding

changes in organizations. A case study is briefly

presented for illustrative purpose, followed by the

discussion and the conclusions.

173

Bolognesi Prado A. and Cecilia Calani Baranauskas M..

Perspectives on using Actor-Network Theory and Organizational Semiotics to Address Organizational Evolution.

DOI: 10.5220/0004437701730181

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 173-181

ISBN: 978-989-8565-60-0

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 THEORETICAL

BACKGROUND

Changes in organizations can be seen as social

activities, since they require discussion and

negotiation among the involved people. To

understand social phenomena in general, the

Sociology traditionally takes one of two opposite

approaches: structuralism or agency (Vandenberghe,

2008). The first defends the primacy of a social

“field of forces” that shapes human behavior, while

the latter sees the individual actions and choices as

the sources of the perceived social reality (Hewege,

2010).

The structuralist approach begins with the

definition of social fact: a human manifestation that

is not part of the physical, biological or

psychological domains. For example, the advent of

money and economics cannot be attributed to the

psychology of a single individual, neither to her

body functions or the laws of matter.

A social fact is recognized by the “power of

external coercion which it exercises or is able to

exercise over individuals” (Durkheim, 2007, p. 10)

giving rise to a structure that is beyond people but

directs their behavior. This vision leads to distinct

treatment for people and objects by placing them in

separate plans. Modeling software with a social

component turns out to be mainly based on

structures that represent people and their relations

(Hendler et al., 2008), limiting their possibilities of

behavior according to a subset of existing social

rules. The dynamics of communities is less

addressed by such software development.

The agency-based approach sees the capacity of

individuals to act independently and to make their

own free choices as the source of social phenomena.

The social structure is just a consequence of the use

of physical and cognitive abilities of individuals

according to their interests and intentions. Following

the same example above, according to this theory,

money was created by people interested to ease

some trade relations and evolved over time, driven

by decisions, needs and innovations, to a more

complex concept.

In the following sections we present the two

theoretical sources that support this work:

Organizational Semiotics and Actor-Network

Theory.

2.1 Organizational Semiotics

The Organizational Semiotics proposes to see an

organization as an information system that uses

signs and norms to coordinate people working

together. Norms capture patterns of behavior and

signs carry meaning and promote communication.

At first, organized groups of people can be seen

as driven by informal norms, whose performance

relies on oral culture, constant negotiation of

meaning, and individual abilities, beliefs and

patterns of action. Some situations ruled by literate

culture, bureaucratic procedures, and normalized

behavior constitute an inner structure, that is

captured in formal norms. Within this structure,

some tasks can be automated and humans replaced

by computers or other technical information

systems. These three layers are nicknamed

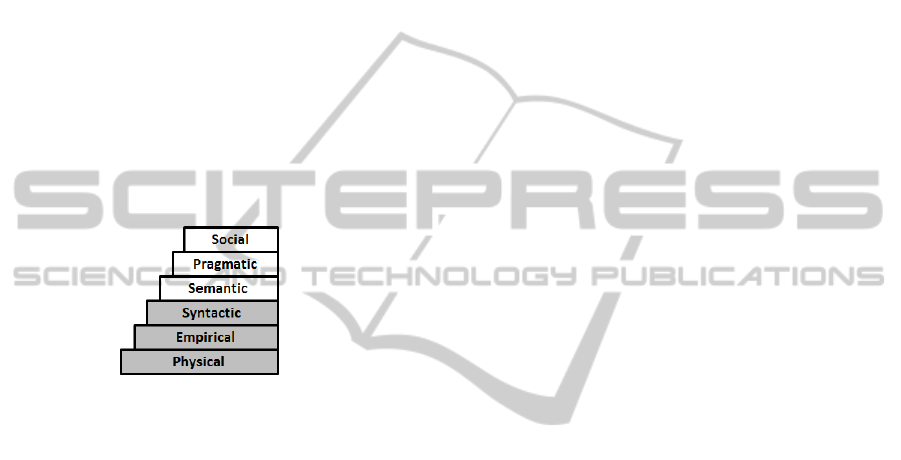

“organizational onion” (Figure 1). Each layer

emerges, relies and depends on the outer ones.

Figure 1: The organizational layers of norms (adapted

from Liu, 2000).

Wright (1958) identified and conceptualized six

distinct types of norms: rules, prescriptions,

directions, customs, moral principles and ideals.

Particularly, prescriptions and customs define the

conducts of people. The former are characterized by

having an explicit issuer or authority and attached

sanctions in case of disrespect. The later have no

such features, being acquired and forwarded by

members of a community by means of imitation and

social pressure and becoming regularities in

individuals’ behavior.

Norms can also be classified as perceptual,

evaluative, cognitive or behavioral, according to the

nature of the phenomenon they govern: to identify

things, to attach a value to things, to grasp causality

in flows of events, and to coordinate activities,

respectively (Stamper et al., 2000). Liu (2000)

shows a general syntax to represent behavioral

norms in organizations:

whenever <condition>

if <state>

then <agent>

is <obliged | permitted | prohibited>

to do <action>.

Semiotic is the science that studies signs as units

of signification and communication. According to

Morris (1938), Semiotics is organized in three

levels: syntactic, semantic and pragmatic. The first

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

174

deals with the structures and relations between signs,

the second with their meanings and the third with the

intentions and contexts of use. Stamper (1996)

added a physical and an empirical level on the lower

end and a social level to the upper level. This is

called the semiotic framework or “ladder” (Figure

2).

The three lower levels (shaded) are often related

to the computational structure of organizations,

encompassing hardware, networks, protocols, data

encoding, logic and software. The three upper levels

correspond to exclusively human attributions: in the

semantic layer data is comprehended and meaning is

assigned; in the pragmatic layer the system is used

with a certain purpose; and if this purpose

presupposes or implies other people participating on

the system, it reaches the social level. This last level

is responsible from negotiation of the meanings of

signs and the definition of norms of behavior.

Figure 2: Semiotic framework, depicting levels in which

signs’ presence and activity can be studied (adapted from

Liu, 2000).

2.2 Actor-Network Theory

The Actor-Network Theory is a recently proposed

theoretical-methodological framework that aims to

provide an interested observer with a “sensitivity” to

better capture how social phenomena evolve. It

proposes to see the human interactions as chains of

associations distributed in time and space that

depend upon the continuous agency of its

participants on each other and whose structure is

dynamic, as a result of this joint action.

ANT is theoretically rooted in the principle that

the basic human social skills are able to generate

only weak, near reaching, and fast decaying ties

(Latour 2005, p. 65). It is also asserted that all the

forces responsible for sustaining the social

aggregations come from the participants of the

phenomenon. Therefore, to explain social structures

such as organizations, that are expected to last

longer and mobilize many different people to work

together, it claims that non-human elements must be

equally addressed.

The participants of the social realm create

associations among each other, intending to obtain

support to propagate forces, share intentions, and

mobilize other allies. These aggregates must be

between humans, between non-humans, frequently

are heterogeneous, but these distinctions are not

considered relevant. Instead, it is fundamental to

identify the role they fulfill in the associations, when

transporting meaning or intentions: as intermediaries

or as mediators.

An actor is an intermediary in a chain of

associations when he or she or it forwards the

actions received without transformation. The

behavior of an intermediary is predictable and the

outputs are determined by the inputs. On the other

hand, a mediator inserts some new behavior to the

system. Mediators modify, distort, enhance or

translate the inputs received. They are creative and

show some variability and unpredictability when

acting upon the others. While faithful intermediaries

often fade out in the studied scenarios, mediators

appear resolving asymmetries and conflicts between

the other actors.

According to ANT, social groups are

performative, their existence relies on the constant

action of the participants upon each other. Therefore,

all the elements involved in a social phenomenon are

actors, in a broader sense that encompass both

human and non-human. No intentionality is assigned

a priori to an actor; the focus is on their potential of

mediation, interaction by physical or cognitive

means, and contribution to the outcome of a

situation.

The process of building the associations among

actors is named translation and depends on the

success of steps in which an actor, in the desire to

change a certain state of affairs, looks for other

actors whose acting skills are beneficial, stimulate

their interests to join, defines roles and ensures

compliance with the responsibilities assumed. A

successful translation must follow these four well-

defined steps (Callon, 1986):

Problematisation: the problem that may be

collaboratively solved must be defined;

Interessment: potential allies have to be

convinced to act conjointly;

Enrollment: the role of each actor in the group is

defined;

Mobilization: the allies must be put to act

associatively and control structures must be

specified to keep them acting as agreed before.

The strength with which these movements unfold

and mechanisms to ensure its stability and

preservation define the success of the formed

PerspectivesonusingActor-NetworkTheoryandOrganizationalSemioticstoAddressOrganizationalEvolution

175

network as a whole. When actors become connected,

the consequences of success or failure spread

through, creating a mutual interest that the group

succeeds. When the translation is effective and the

various actors are driven to act as one through the

mechanisms of mutual control, their complexity is

abstracted in a black box. So the network becomes

itself an actor.

From the methodological viewpoint, ANT

proposes to “follow the actors in their weaving

through things they have added to social skills so as

to render more durable the constantly shifting

interactions” (Latour 2005, p. 68). This quest is

oriented to the sources of uncertainties a researcher

may face when exploring social groups, in an

allusion to the principle of uncertainty from the

quantum physics. The observer is always accounted

as part of the representation and explanation of the

studied phenomena. Each actor studied has his own

frame of reference and shifting from one frame to

another always adds some uncertainty.

ANT recommends that we follow the actors

closely, investigating the circulating entities that

make people act, understanding how each actor is

recruiting the others, looking myopically to the

phenomena in order to grasp details and covering the

whole scenario (Fioravanti and Velho, 2010). When

inquired about what make them act, actors are

granted the ability of reflection and theorization,

their explanations must be fully respected, including

the used language and the figurations given to the

causes of actions.

It is also advised to abandon some distinctions

prior to the analysis: local and global are not

hierarchically separated, but flattened and

differentiated only by the extension and durability of

their connections; truth and error are values applied

by actors with different strengths in each frame of

reference and not a researcher’s filter; and both

human and non-human actors must be monitored

symmetrically, being equally left to express

themselves and be attributed some power or agency.

There is a list of occasions where objects become

visible as actors and their role as mediators is

enhanced enough to be studied: breakdowns,

accidents and the proposal of innovations and

novelties. When it is not possible to observe objects

in situ, it is allowed to recover objects’ histories and

the state of doubt or crisis in which they were born.

3 RATIONALE FOR COMBINING

ANT AND OS

The Organizational Semiotics acknowledges the

informal layer as the place for discussion,

negotiation and uncertainties. Only when a state of

affairs is stable, norms can be formalized and shifted

successively to the formal and technical layers. This

movement may lead to give up individual meanings

and intentions, and rendering impersonal forces that

apply the norms.

Since Organizational Semiotics is widely used to

provide conditions to develop and deploy software

into enterprises and for social groups (Bonacin et al.,

2012; Liu and Benfell, 2011; Gazendam et al.,

2003), it searches for the structural features of these

sets of people, being less relevant how and who in

particular defined the structures. Given this intense

appeal to pervasive and impersonal norms, OS’s

character is predominantly structural.

The ANT comes as a conciliatory proposal

between agency and structure, in a position that can

be named structurationist (Vandenberghe, 2008).

For being focused on actors and the means by which

they can interfere in the course of actions, ANT

proposes that one of the goals of actors’ movements

is to build a stable structure that, once established,

governs future actions in a certain degree.

Patterns strengthened by the passage of time and

the creativity required by uncertainties in the future

are the essentials for society. Latour (2000)

metaphorically represented this by the figure of

roman deity Janus (Figure 3), who simultaneously

looks to the past and to the future, mediating

stabilized affairs and the need for innovation.

Figure 3: Two-faced Janus, from roman mythology, is

used by ANT as a metaphor for the ambivalent character

of the social aggregates: existing structures mold behavior

(ancient face at left, looking to the past) and new behavior

redefines structures (younger face at right, looking to the

future). Extracted from Yonge (1880).

ANT highlights that the “fields of forces”

generated by norms according to OS’ perspective

(Al-Rajhi et al., 2010) are instead the sum of social

forces generated, stored and replied by actors and

conducted through the associations between them,

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

176

regardless of being human or not. Customs are not

seen as anonymous anymore: they reach people

through the associations each actor has. Although

they do not have an authoritative issuer and neither

an explicit penalty for being broken, ANT affirms

that there is a process of translation that make people

behave accordingly and that can be observed and

studied. This process is better perceived in moments

of group creation or of instability.

Norms are embodied in documents and devices.

Sharing patterns of behavior is not always a face-to-

face phenomenon. In this sense, both OS and ANT

share a semiotic-materialism viewpoint (Law, 2009).

Knowing the sources of these patterns is

fundamental when someone is interested in changing

them. Besides, knowing the nature of these

reservoirs of rules, examples, laws and models – as

human or non-human – allows us to choose an

approach to tackle the change.

4 ADDRESSING

ORGANIZATIONAL

EVOLUTION: A PROPOSAL

This paper presupposes the scenario described by

Sani et al. (2012) in which innovation and changes

come from the outermost layer of the semiotic

onion. Since at this point norms may be conflicting

and provisional, there are behaviors and concepts

that are not universal, but localized in individuals or

subgroups with shared opinions. To grasp these

subtleties for further analysis, the following steps are

proposed:

1. Follow the actors through their daily activities

related to the business processes to be

understood, changed or improved. Let us call

each of them as focal actors (Carrol et al.,

2012);

2. Identify actors’ patterns of behavior and

represent them as the existing norms. Provide an

identifier for each norm (Sun et al., 2001) for

the sake of faster referencing;

3. Identify the actors that are promoting such

norms through successful translations that keep

agents working according to their interests. Let

us call them associates;

4. Question about the unfulfilled intentions of

existing norms, i.e., undeveloped or

unsuccessful translations;

5. Follow the chains of intermediaries and

mediators that converge into the associates, in a

recursive process.

The outcomes of these steps can be used to find

points of conflict or inconsistency, and can be scored

using the proposed syntax for each norm:

Norm <norm-id>:

whenever <condition>

if <state>

then <focal-actor>

is <obliged | permitted | prohibited>

by <associates>

to do <action>.

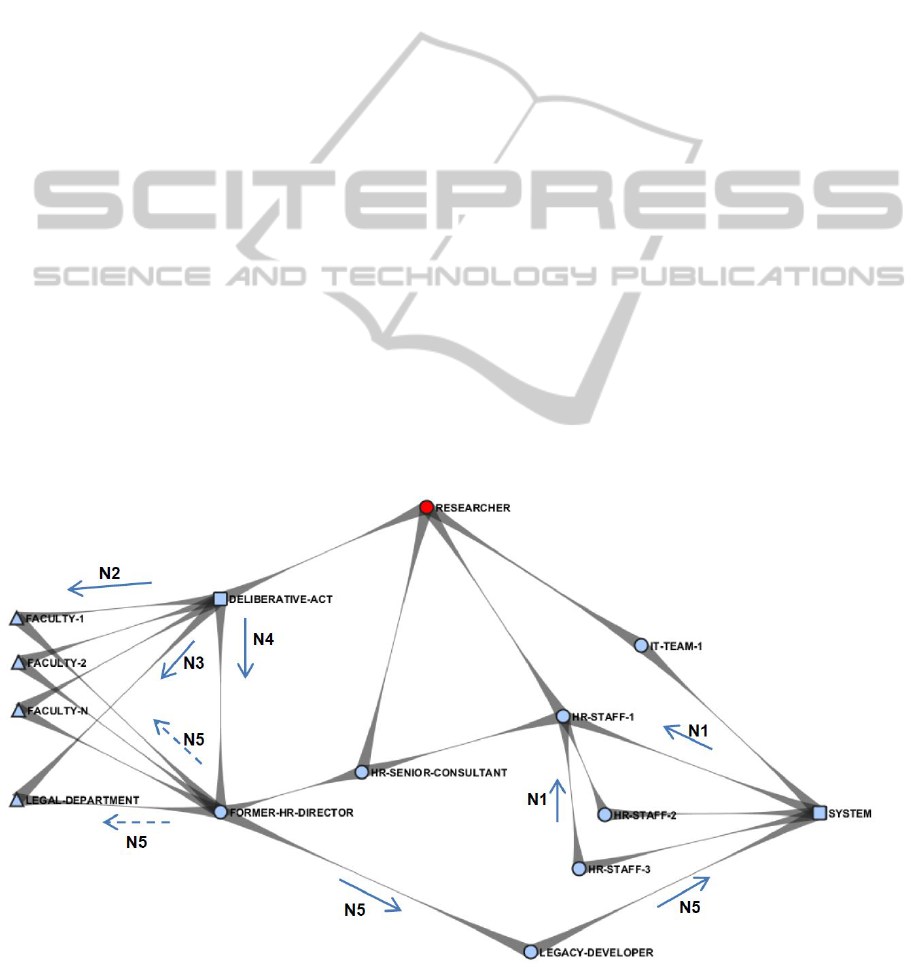

The final product of the steps can be summarized

using a graphical notation to represent all the

involved actors and the norms they are subjected to.

Human actors are represented as circles, non-human

as squares and composite entities (human and non-

human together, as for instance, external

organizations) are depicted as triangles. Edges show

associations between actors. Arrows represent the

flows of influences that feed norms; solid ones are

actual perceived norms and dashed ones are intended

only. This is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: proposed representation for the different types of

actors and the norms of behavior they exhibit and enforce.

5 AN ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLE

FROM A CASE STUDY

A case study was conducted following an action-

research approach (French and Bell, 1973), since the

focus of the participants were in producing changes

in a real-world situation and improving the practices

of an organization. ANT and OS were used as tools

when applicable, and the successive trials and cases

of success informed the method described in this

paper.

The IT team of a public University was requested

by the Human Resources Department (HR) of the

same institution to build a web version of a legacy

system, already used in client-server mode, which

was custom built by a third-part software factory

fifteen years ago. This moment was seen by the

managers as an opportunity to document, review and

PerspectivesonusingActor-NetworkTheoryandOrganizationalSemioticstoAddressOrganizationalEvolution

177

improve business processes.

The dialogues below were simplified and

translated from a series of conversations with the

involved actors, following their own daily activities.

We started from the main user of the system,

member of the Human Resources Department staff,

who we will refer to as HR-STAFF-1:

HR-STAFF-1: When I use this screen, I must first

type the teacher’s name and ID, set the status to

‘1’ and click ‘save’. Then change the status to ‘2’

and click ‘save’. Again, change the status to ‘3’

and ‘save’, and only now I can input the other

data: workplace, date of admittance and so on.

Then click ‘save’ again and it’s done.

When asked about the reason for that behavior,

she just replied:

HR-STAFF-1: When I started to work here, my

colleagues told me to do so. And also, see: when I

insert a new teacher, the only value the system left

for me to choose for ‘status’ is ‘1’. And only when

‘status’ reaches ‘3’, the system enables the other

fields for me.

In fact, analyzing the available source code, the

IT team confirmed that such behavior was

deliberated, but produced no intermediary effect or

outcome other than enabling and disabling fields on

the form. This brings us to the first recorded norm:

Norm N1:

whenever teacher data is inserted into

HR database

if it is a new teacher

then HR-STAFF

is obliged

by SYSTEM, HR-STAFF (coworkers)

to set the status to 1, 2 and 3 in

sequence.

The HR staff member was sometimes advised by

a senior consultant, who worked there since the time

the legacy system was being developed. Although

she does not use the system anymore, she provided

some additional information about the motivations

for the development of that software:

HR-SENIOR-CONSULTANT: there is a

Deliberative Act that says the hiring process of a

new teacher must begin at a Faculty, and then

wait for approval by the Legal Department. Only

if approved, HR proceeds with registration. The

former HR Director believed that the system must

reflect such rule, and all the involved workers

must use the system.

The Deliberative Act is an official document,

available at the local intranet for the researcher’s

inspection. Analyzing the text and the senior

consultant’s story, new norms were detected:

Norm N2:

whenever hiring a new teacher

if the process is beginning

then FACULTY

is obliged

by DELIBERATIVE-ACT

Figure 5: Actor-network and the flow of norms gathered during case study. Some arrows, although existing in the real data,

were omitted for the sake of readability.

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

178

to send the filled forms to Legal

Department.

Norm N3:

whenever hiring a new teacher

if the forms are filled by Faculties

then LEGAL-DEPARTMENT

is obliged

by DELIBERATIVE-ACT

to verify their content. If approved,

send them to Human Resources; if

rejected, send them back to

Faculty.

Norm N4:

whenever hiring a new teacher

if the forms are approved by Legal

Department

then Human Resources Department

is obliged

by DELIBERATIVE-ACT

to insert teacher’s data on the database.

Norm N5:

whenever hiring a new teacher

if the forms moved in workflow

then FACULTY, LEGAL-DEPARTMENT, Human

Resources Department

are obliged

by FORMER-HR-DIRECTOR

to inform process status, meaning:

1-Forms filled by Faculty;

2-Legal Dept. approval;

3-Registering in the HR database.

The senior consultant also informed that norm

N5 was not accepted by Faculties and Legal

Department, since they were not interested in using

the Human Resources software only to inform the

hiring process’ situation. Therefore the FACULTY

and LEGAL-DEPARTMENT actors chose not to

follow N5, being subject only to N2 and N3. Figure

5 represents all actors studied and the scenario of

norms they are enforcing and to which they are

subject.

The detection of these points of conflict in the

norm flow leads to the situation where an

organizational structured can be improved: either N5

is discarded, by negotiation with the current Human

Resources Director, or its translation is completed

by convincing Faculties and Legal Department to

use the system. This decision is to be taken by the

current Human Resources Director, in negotiation

with Legal Department and Faculties.

5.1 Discussion

By knowing the role of the actors as intermediaries

or mediators, and being aware of the process of

translation, we are able to find the trials of

introducing innovations. For instance, the former

HR Director translated norms N4 to N5 according to

his own interests, being a mediator. The legacy

software developer, on the other hand, acted as a

faithful intermediary, implementing such behavior

on the system (see Figure 5).

Non-human actors share the responsibility of

keeping the others acting as expected by their

designers. The SYSTEM kept HR-STAFF

performing according to the FORMER-HR-

DIRECTOR’s intentions, although the other

stakeholders, who were not connected to the system,

ignored the norm N5.

During the representation of the actor-network,

associations between actors do not always carry

norms. They represent the flows of information and

interests among all the involved entities. For

instance in the case study, HR-SENIOR-

CONSULTANT does not enforce or is subject to

any norm. She provided de path through which the

norms N2 to N5 became known. The ANT

representation makes explicit the presence of this

informant as a source of uncertainty. The role of the

researcher is also highlighted as an active actor.

Although incomplete translations do not exist as

a global shared behavior, they play an important role

in the dynamics of organizations, because from the

ANT point of view, they are precursor of norms or,

as seen in the case study, generate local patterns of

action that may be obsolete and subject to

improvement. Using ANT, local sub-cultures can be

disassembled, analyzed and explained; for example,

the existence of norm N1 was maintained by the

SYSTEM and the HR-STAFF by means of a

custom, although the justification for such behavior,

FORMER-HR-DIRECTOR, was not directly acting

anymore.

It is also noteworthy that the passage of norms

from the formal to the technical layer is not a

passive process of diffusion, but instead subject to

the active interference of actors' interests,

capabilities and comprehension, for instance, the

sequence of translations N4 → N5 → N1. Norms

always reach people through a network of

associations that may be heterogeneous in actors’

nature and intentions.

6 CONCLUSIONS

Systems design for a changing organization is far

from being a solved problem. The Actor-Network

Theory argues that individuals’ intentions are the

source of social structure and provides a good

methodological and theoretical support to find those

interactions and understand how such structure

emerges and is maintained. Organizational

Semiotics, on the other hand, has a long tradition in

PerspectivesonusingActor-NetworkTheoryandOrganizationalSemioticstoAddressOrganizationalEvolution

179

providing a deep understanding of the enterprises

and, once patterns are established, guiding the

software development.

By seeing the whole organization as a single

information system and considering that all actors

involved – people, technical devices and other

objects – may have the same importance in the

social level, through the proposed method and

representation, we were able to trace back the norms

flow through the network of actors and reach their

sources, enabling to negotiate the change with the

appropriate stakeholders of a case study.

This work will be continued by experiencing the

presented approach in the design of social network

systems (Pereira et al., 2011). Given the nature of

these environments, with few enforced rules and

norms emerging organically, the system design

requires the capability to deal with structural

instabilities, uncertainties and continual evolution.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is part of the EcoWeb project, funded by

CNPq through the process 560044/2010-0.

REFERENCES

Al-Rajhi, M., Liu, K., and Nakata, K., 2010. A Conceptual

Model for Acceptance of Information Systems: an

Organizational Semiotic Perspective. Proceedings of

the Sixteenth Americas Conference on Information

Systems, Lima, Peru.

Bonacin, R., Reis, J. C., Hornung, H. and Baranauskas, M.

C. C, 2012. An Ontological Model for Representing

Pragmatic Aspects of Collaborative Problem Solving.

IEEE 21st International WETICE. DOI 10.1109.

Callon, M., 1986. Some Elements of a Sociology of

Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the

Fishermen of St. Brieuc Bay. In John Law (ed.),

Power, Action and Belief: A New Sociology of

Knowledge.

Carroll, N., Richardson, I. and Whelan, E, 2012. Service

Science: An Actor-Network Theory Approach.

International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and

Technological Innovation, v.4, n.3.

Durkheim, E., 2007. The Rules of Sociological Method.

Ed. Martins Fontes (Brazilian Portuguese edition).

Fioravanti, C., Velho, L., 2010. Let’s follow the actors!

Does Actor-Network Theory have anything to

contribute to science journalism? Journal of Science

Communication, JCOM 9(4). International School for

Advanced Studies. ISSN 1824-2049.

French, W. L., Bell, C., 1973. Organization development:

behavioral science interventions for organization

improvement. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall.

Gazendam, H. W. M., Jorna, R. J. & Cijsouw, R. S.

(2003). Dynamics and change in organizations:

Studies in organiational semiotics. Boston: Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Hendler, J., Shadbolt, N., Hall, W., Berners-Lee, T.,

Weitzner, D., 2008. Web Science: An Interdisciplinary

Approach to Understanding the Web. Communications

of ACM, v. 51, n. 7.

Hewege, C. R. (2010). Resolving structure-agency

dichotomy in management research: Case for adaptive

theory research methodology. 24th Annual Australian

and New Zealand Academy of Management

Conference.

Holt, D. T., Armenakis, A. A., Field, H. S. and Harris, S.

G., 2007. Readiness for Organizational Change: The

Systematic Development of a Scale. Journal of

Applied Behavioral Science, vol. 43, no. 2.

Jacobides, M. G. and Winter, S. G., 2012. Capabilities:

Structure, Agency, and Evolution. Organization

Science. Vol 23, no. 5, pp. 1365–1381, INFORMS.

ISSN 1047-7039.

Jacobs, A. and Nakata, K., 2012. Organisational Semiotics

Methods to Assess Organisational Readiness for

Internal Use of Social Media. Proceedings of the

Eighteenth Americas Conference on Information

Systems. Seattle, Washington, August, 2012.

Latour, B., 2000. Science in action: how to follow

scientists and engineers through society. Ed. UNESP

(Brazilian Portuguese edition).

Latour, B., 2005. Reassembling the Social: An

Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford

University Press.

Law, J., 2009. Actor-Network Theory and Material

Semiotics.

The New Blackwell Companion to Social

Theory. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Liu, K., 2000. Semiotics in information systems

engineering. Cambridge, England: Cambridge

University Press.

Liu, K. and Benfell, A., 2011. Pragmatic Web Services: A

Semiotic Viewpoint. ICSOFT 2009, CCIS 50. J.

Cordeiro, A. Ranchordas, and B. Shishkov (Eds.). pp.

18–32. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Morris, C. W., 1938. Foundations of the theory of signs.

Chicago University Press.

Pereira, R., Miranda, L. C., Baranauskas, M. C. C.,

Piccolo, L. S. G., Almeida, L. D. A., Reis, J. C., 2011.

Interaction Design of Social Software - Clarifying

requirements through a culturally aware artifact. IEEE

International Conference on Information Society.

Sani, N. K., Ketabchi, S., and Liu, K., 2012. The Co-

design of Business and IT Systems: A Case in Supply

Chain Management. ICISTM 2012, CCIS 285, pp. 13–

27, 2012. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Soares, A. L., Sousa, J. P.,, 2004. Modeling social aspects

of collaborative networks. Collaborative Networked

Organizations. A research agenda for emerging

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

180

business models. Camarinha-Matos, Luis M.;

Afsarmanesh, Hamideh (Eds.). Springer-Verlag.

Stamper, R. K., 1996. Signs, Information, Norms and

Systems, in Holmqvist, P., Andersen, P.B., Klein, H.

and Posner, R. (Eds.), Signs of Work: Semiotics and

Information Processing in Organisations.

Stamper, R., Liu, K., Hafkamp, M. and Ades, Y., 2000.

Understanding the Roles of Signs and Norms in

Organisations. Journal of Behaviour and Information

Technology, vol. 19 (1).

Sun, L., Chong, S. and Liu, K., 2001. Articulation of

Information Requirements in e-Business Systems.

Proceedings of the Seventh Americas Conference on

Information Systems – AMCIS.

Underwood, J., 2001. Translation, Betrayal and Ambiguity

in IS Development. Proceedings of IFIP WG8.1

Working Conference on Organizational Semiotics,

Montreal, Canada.

Vandenberghe, F., 2008. Review of the book Structure,

Agency and the Internal Conversation by Margaret S.

Archer. Revue du Mauss, June 2008. Available online

at www.journaldumauss.net.

Wright, G. H., 1958. Norm and Action. Available online at

www.giffordlectures.org/Browse.asp?PubID=TPNOR

M.

Yonge, C. M., 1880. Young Folks' History of Rome.

Project Gutenberg.

PerspectivesonusingActor-NetworkTheoryandOrganizationalSemioticstoAddressOrganizationalEvolution

181