Conceptual Framework for Design of Collaborative Environments

Cultivating Communities of Practices for Deaf Inclusion

Daniela de Freitas Guilhermino Trindade

1,2

, Cayley Guimaraes

1

and Laura Sanchez Garcia

1

1

Informatics Department, Federal University of Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil

2

Center of Technological Sciences, State University of Paraná, Bandeirantes, Brazil

Keywords: Human Factors, Accessibility, Deaf Issues, Design of Interaction and Interface, Communities of Practice.

Abstract: Members of the Deaf communities have been excluded for several years. There is a need for computational

tools that take into account their peculiarities so that the Deaf may fulfill all their human possibilities. Even

the systems that were supposedly designed for the Deaf present several problems (e.g. not in Sign Language

(SL)). Communities of Practice (CP - a group of people who share some interest on a topic, and get together

to better understand that topic) cultivate interactions. Interactions through collaborative activities mediated

by computers should be used for social inclusion of the Deaf and Knowledge Creation (KC – a social

process that encourages learning and development of skills). This article has two main objectives: first, it

presents the results of an ethnographic study of a CP with Deaf and non-Deaf members to study SL. Second,

the observations from the ethnographic study (based on collaboration and communication theories) allowed

the researchers to determine some requirements, that are compiled and presented here as a Conceptual

Framework to inform design of Inclusive Collaborative Virtual Environments (ICVE) to be used to cultivate

CP for Deaf inclusion.

1 INTRODUCTION

Deaf communities live a historical moment in their

quest for the social rights they have been denied for

many years. According to Fernandes (2006, p.1),

“the right to use Sign Languages (SL) in different

contexts of social interaction and knowledge

access” is one of the most important of these rights.

The use of SL gives the Deaf the ability to

participate in their social inclusion and is essential

for citizenship. Mantoan (2005 p. 2) tells us that

“[…] inclusion is our ability to understand and

recognize the other, and, therefore, have the

privilege of living and sharing with different people

[…]”. In that regard, members of the Deaf

communities need to have their peculiarities

acknowledged so that they can fulfill all their human

possibilities.

Communities of Practice (CP) cultivate

interaction, and should be used to provide the Deaf

with new possibilities, thus widening the

expectations of collaboration with members of other

communities. Such collaborations are paramount for

the socialization and development of the Deaf’s full

potential. CP gather people of different skills and

experiences, centered around a given topic of study

(e.g. Deaf issues) in order to learn more about that

topic. Each member of a CP contributes with her

unique set of skills to generate ideas, solve

problems, make decisions, create knowledge. The

interactions within a CP for knowledge creation (KC

– a social process that encourages learning and

development of skills) or for task performace are

beneficial for learning (e.g. the learning of SL).

These interactions within a CP increase the systemic

learning sinergy (as opposed to individual action)

and should be mediated by computers.

Interactions through collaborative activities

mediated by computers are relevant for social,

historical, political and human formation and may

contribute to the creation of the Deaf identity.

However, the existing Computer Supported

Cooperative Work (CSCW) frameworks lack

physical, empirical and social aspects when it comes

to accessibility and inclusion in general, and the

Deaf issues in particular. Mainly, CSCW systems

are designed for users of oral language and users

who have some Information and Communication

Technologies (ICT) skills.

Even among the systems that were suppossedly

designed for the Deaf, Trindade et al., (2011) found

206

de Freitas Guilhermino Trindade D., Guimaraes C. and Sanchez Garcia L..

Conceptual Framework for Design of Collaborative Environments - Cultivating Communities of Practices for Deaf Inclusion.

DOI: 10.5220/0004441802060215

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 206-215

ISBN: 978-989-8565-60-0

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

several inadequacies: the use of a limited set of SL

(i.e. sets that do not cover the entire language; and

do not allow the user to add or change the signs on

that set); the use of pre-defined videos to convey

information in SL, thus limiting interaction and

sharing of information; the use of alphabet and

spelling (which are but a small part of SL); limited

learning and information coverage; the use of the

system as a mere data repository, which limits its

possibilities to elaborate queries, among other

issues.

Almeida (2011) presents a social-technical

approach in the “FAware” framework to be used in

the design of awareness in web-based Inclusive

Collaborative Systems (ICS). This research proposes

a conceptual framework that broadens the scope of

awareness. Additionally, the proposed framework

extends the focus to other requirements for

collaboration and KC in CP formed by Deaf and

non-Deaf members. In order to derive the proposed

framework to inform design of collaborative systems

for Deaf inclusion and support of the social

construction of knowledge, such CP was cultivated.

The study of the interactions among the

participants allowed for the observation of

specificities that needed to be addressed. The

analyses of such observations are presented in three

(3) main foci: elements that influence KC, the use

of Acts of Speech and conversation parameters

and principles of cooperation.

The remainder of this article presents the main

theories that were the basis of the research (section

2). Section 3 presents the methodological steps used.

Section 4 presents an ethnographic study performed

with the CP. Section 5 presents the proposed

framework. Section 6 offers some considerations

and future work.

2 THEORETICAL BASIS

The ethnographic study of the cultivation of the CP

was based on the relation and combination of some

concepts: Communities of Practice, Knowledge

Creation and transformation, communication and

cooperation theories, conversation analysis among

others.

2.1 CP and Knowledge Creation

A Community of Practice (CP) is a group of people

who share an interest or passion for some topic and

who try to interact regularly in order to increase their

knowledge about such topic (Lave and Wenger,

1991); (Wenger, 2010). CP build relations and ties

among its members and allow for collective learning

(Vidou et al., 2006). CP have a domain (the topic),

community (people with shared interests) and

practice (process used within the CP to learn about

the topic.

CP creates a collaboration arena that promotes

cooperation and KC by allowing communication and

interaction among its members so that knowledge

and experiences are shared in a coordinated manner.

Usually, a CP provides a shared repository of

routines, vocabulary, instruments, methods and

techniques, actions and concepts that the CP has

built or adopted throughout its existence (Silva,

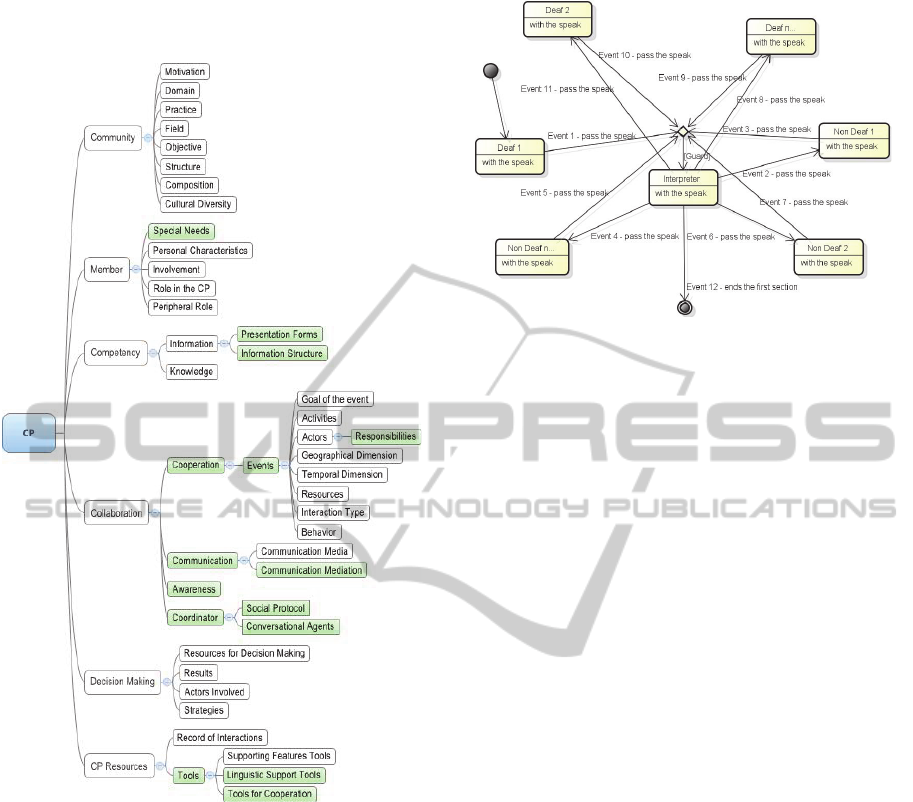

2010). Table 1 compiles several relations and

concepts about CP from the literature, including the

ontology from Tifous et al., (2007).

Table 1: CP – Concepts and Relations. Source: adapted

from Tifous et al., 2007.

CP – Main Concepts Authors

COMMUNITY

Motivation

Wenger (2001) Domain

Practice

Field

Tifous et al.,

(2007)

Goal

Structure

Composition

Cultural diversity

Langelier and

Wenger (2005)

MEMBERS

Personal Characteristics

Miller (1995),

Tifous et al.,

(2007)

Type of envolvimento

Tole

Peripheral role

COMPETENCE Type of Competence Tifous et al. (2007)

COLLABORATION

Collaboration Goals

Vidou et al.,

(2006)

Collaborative Activities

Roles involved

Geographic Dimension

Temporal Dimension

Collaboration resources

Communication means

Types of interaction

Engagement Deaudelin et al.,

(2003),

Weiseth et al.,

(2006)

Coordination

DECISION-

MAKING

Decision-making resources

Tifous et al.,

(2007)

Results

Actors

Strategies

CP RESOURCES

Record of interaction

CP tools

A CP is comprised of several elements (e.g.

actors, resources, competences, activities etc.) and

their inter-relations needed to achieve the goals of

ConceptualFrameworkforDesignofCollaborativeEnvironments-CultivatingCommunitiesofPracticesforDeaf

Inclusion

207

the CP. The ontology proposed by Tifou et al.

(2007) presents the main elements, their semantics,

and other contexts of CSCW, which may be used in

KC tools to aid the learning process in CP.

In order to appropriate knowledge, one must

additionally combine, systematize and apply it. KC

occurs when the members of a CP share experiences,

observe and assimilate specific skills brought in by

each member. KC takes place in a CP when its

members exchange ideas for decision-making and

problem solving.

Knowledge is characterized as a set of items of

contextualized information containing the meanings

inherent to the agent that possesses it; its semantic

content is a function of the set of items of

information that it contains, the links with other

units of knowledge and by the contextualization

process (Santana and Santos, 2002).

According to Bukowitz and Williams (2002), the

TIC comprised the main forces that brought into

evidence KC. The TIC allowed people to share large

amounts of information without concerns about

geographical or temporal barriers. Information

sharing is the first step towards KC: a continuous

social process of goal clarification that negotiates

commitment and encourages mutual learning and the

development of skills (Carroll et al., 2003).

Information sharing can be tacit or explicit.

Takeuchi and Nonaka (2008) tell us that tacit

knowledge is related to one’s personal experiences,

skills, beliefs and daily life situations. Explicit

knowledge refers to the contents found in texts,

manuals, graphics, spreadsheets and other types of

registered documents that can be shared. Knowledge

Conversion is the process that changes one type of

knowledge into the other. Nonaka and Takeuchi

(1997) describe four types of knowledge conversion

in the SECI:

Socialization (tacit to tacit): share and create a

tacit knowledge through direct experience;

Externalization (tacit to explicit): articulate the

tacit knowledge through dialog and reflection;

Combination (explicit to explicit): occurs when

an individual systematize and applies the explicit

information and knowledge;

Internalization (explicit to tacit): one learns and

acquires tacit knowledge through practice.

The use of the SECI model within a CP allows for

KC.

2.2 Communication and Cooperation

The CP formed for this research was culturally rich,

diverse, faced with different contexts and needs.

This configuration prompted the researchers to

incorporate some classical theories (e.g. Acts of

Speech and Principles of Cooperation) in order to

enhance the contribution of the present research.

Such theories investigate the communication

processes, its signs, meaning attribution and

interpretation in their communicative approaches.

Their descriptive powers allow for important

insights about the social rules, the process of

communication and cooperation to coordinate the

rational behavior geared towards a goal.

The theories of communication and cooperation

may help the Human-Computer Interaction (HCI)

field to inform design of collaborative environments,

to the extent that they offer adequate mechanisms

for the user to make decisions on how to interact in

the different contexts of collaboration.

The Acts of Speech Theory (Austin, 1962,

Searle, 1969, 1979) work with the premise that

language isn’t used only to represent states in real

world: languages also have an impact on such

reality, and differentiate actions. Austin (1962)

proposes three acts of speech: the locutory act

occurs at enunciation time, especially the act of

pronunciation by a set of articulated phonemes

according to the grammar of a language; the

ilocutory act represents an intention of the speaker,

and the intonation used can be translated into values;

the perlocutory act is related to the resulting effect,

in the interlocutor, caused by the uttered sentence.

Searle (1979) extends Austin (1962) and

describes five classic categories for the ilocutory act:

Assertives (instructions, affirmations): they

express the commitment to the truth in regards to

the expressed proposition;

Directives (request, command): they describe

diverse attempts by the speaker to persuade the

listener to perform some action;

Declaratives: they alter the state of reality when

it is uttered, by whom, for whom;

Commissives (promises): they are used to

commit the speaker to perform some action in

the future;

Expressives (reprimands, condolences): they

have the goal of attracting the attention to a

psychological state or attitude.

Grice (1975) complements the theory with

Principles of Cooperation. The author presents four

maxims that must be considered for a successful

communication: Quantity, Quality, Relevance and

Manner.

HCI makes use of such principles, of which rules

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

208

of consistency (related to manner) (Shneiderman,

1998), system visibility status (related to the quality)

and the minimalist design (quantity, quality and

manner) (Nielsen, 1996) are examples. For Barbosa

(2006), a complex challenge for HCI is to use such

theories to inform design of systems that will

support the treatment of expressions that reflect the

psychological attitudes of the user. These

considerations are discussed further in Section 4.

2.3 Ethnomethodology and

Conversation Analysis

Ethnomethodology is a method that HCI borrows

from Sociology and Anthropology to better

understand the intrinsic relations that involve human

actions. Ethnomethodology is singularly based on

social construction, mainly, in the method used to

collect and treat data: such manner allows for a more

precise description of the interaction among users,

their tasks, and of the technology being used in a

real environment. This rich description is of the most

importance for HCI (Garfinkel, 1967).

Conversation Analysis (CA) comes from

ethnomethodology and cognitive anthropology and

tell us that “[…] all aspects of action and social

interaction may be examined and described in terms

of a pre-determined or institutionalized structural

organization” (Marcuschi, 2003, p.6). Sacks,

Schegloff and Jefferson (1974) demonstrate that

people organize themselves socially through

conversations. The authors observe that any given

conversation have the following properties: speakers

take turns; usually, only one person is speaking at a

given time; more than one speaker at a time are

common, but brief; transitions (from one speaker to

the other) without intervals and without

juxtaposition occur more often than transitions with

brief intervals of minor juxtaposition; the order and

the length of turns are not fixed; the length of the

conversation is not properly specified; the relative

distribution of turns of who is speaking when is not

previously specified; the number of participants may

vary. Such model should be taken into account in the

design of ICVE.

In order to produce and maintain a conversation,

the people involved must share a minimum of

common knowledge (e.g. linguistic skills, cultural

involvement and the ability to handle social

situations) (Marcuschi, 2003). The German linguist

H. Steger (apud Marcuschi, 2003) distinguishes two

types of dialogue: 1) Asymmetric Dialogues, in

which one of the participants has the right to initiate,

coordinate, guide and conclude the interaction, along

with the power to exert pressure on the other

participant; 2) Symmetric Dialogues, in which the

various participants supposedly have the same rights

in the organization of the conversation (i.e. choice of

words, theme, time etc.).

Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson (1974) elaborate

a model for conversation based on the system of

turns (i.e. each speaker takes her turn to speak),

where each speaker has her turn at a time; turns are

taken with the least amount of space and

juxtaposition of speech and that a turn may vary in

form, content and duration. The model is as follows:

1) One speaker at a time - this is the basic rule of

conversation: in general, the speakers alternate turns,

and each waits for the other speaker to finish to start

speaking; 2) Who has the right to speak and when

- this rule has two techniques: a) the current speaker

chooses the next speaker, thus initiating a new turn;

b) the current speaker stops, and the next speaker

takes her turn by choosing herself.

Additionally, in a conversation, simultaneous

speech may occur, along with juxtaposition of

voices. The mechanisms used to repair such events

have an important role in organizing conversations,

and should be tied to the techniques of taking turns.

Marcuschi (2003, p. 27) adds that “[…] just like the

taking of turns and the simultaneous or juxtaposed

speech, also the pauses, silences and hesitations are

important local organizers that may allow for

relevant moments for the transition from one turn to

the next”.

3 METHODOLOGICAL STEPS

The current research is exploratory in nature, when it

analyses the needs and challenges related to a

specific group (i.e. that of the Deaf people and their

need to communicate among themselves and with

non-Deaf people): an area with scarce literature, for

which it is difficult to derive precise working

hypothesis. The objectives of this research

determined the following methodological steps:

Ethnographic Study: the researchers performed

an ethnographic study to acquire qualitative data

about the requirements necessary for

communication, coordination, cooperation and

knowledge creation in a CP with Deaf and non-

Deaf members.

Elaboration of the Preliminary Model of the

Conceptual Framework: review, integration

and adaptation of collaboration, CP and

knowledge creation models. The results obtained

ConceptualFrameworkforDesignofCollaborativeEnvironments-CultivatingCommunitiesofPracticesforDeaf

Inclusion

209

from the ethnographic study was combined with

these models and incorporated into a proposed

conceptual framework to inform design of virtual

environments, conducive of cultivating CP for

Deaf inclusion.

Creation of the Structural and Behavioral

Models: the preliminary conceptual framework,

characterized as domain ontology, was modeled

in its structural and behavioral aspects as per the

approach of Martins (2009).

Section 4 describes the ethnographic study

performed with a CP with Deaf and Non-Deaf

members. Section 5 presents the proposed

framework.

4 ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY

An ethnographic study was conducted to investigate

the needs for collaboration. The topic of interest of

the CP was that of “knowledge creation about the

phonology of Libras”.

4.1 Collaborative Meetings of the CP

The weekly meetings were previously scheduled as

per demands and availabilities of the members. Each

meeting lasted approximately for two (2) hours, over

a period of three (3) months. Each meeting required

the presence of at least two members of the Deaf

community, an interpreter, and three members or the

research group (to coordinate the meetings). The

non-Deaf interpreter allowed for communication

with a neutral interpretation (i.e. her role as

interpreter could not influence or intervene with the

Deaf’s ideas). Additionally, as a member of the CP,

she also acted as a motivator to attain members’

participation, as well as she acted as a contributor,

with her own set of knowledge and skills.

Deaf members had the main responsibility to

share their knowledge about the phonology of

Libras. They were responsible for the bulk of the KC

process through sharing of their experiences and

skills. The researchers were the mediators of the

collaboration process, organizing and coordinating

the activities. The meetings followed guidelines

from INES (National Institute of Deaf Education –

www.ines.gov.br) to conduct the meetings and

overcome obstacles in the communication barrier

between Deaf and non-Deaf members: for example,

the use short and complete; no use of figurative

speech; maintain a frontal, direct look when

addressing the group; use the semi-circle format so

that each member could see the other, and the visual

resources available. The meetings had cards with

each hand configuration of Libras, white boards for

sketches, and a computer system with a compilation

of various parameters of the phonology.

4.2 Collaborative Meetings Analysis

The meetings were recorded. The researchers used

the videos, interviews, conversations and notes taken

during the meetings for the analysis, which focused

on three main factors: the elements that influenced

knowledge creation; acts of speech and

conversational organization; and principles of

cooperation. The analysis allowed the mapping of

the implications of the occurrences in order to

inform design of Inclusive Collaborative Virtual

Environments (ICVE). The analysis had as its sub-

units the tasks the members performed in each

meeting (e.g. give an example of a sign for a certain

hand configuration; provide signs that could be

derived form a given sign, etc.). The actions were

grouped according to their role in the collaboration

in order to match the analyzed parameters.

4.2.1 Elements that Influenced KC

In order to promote KC in a CP it is necessary to

guarantee that the flow of information (collect, store,

analyze, disseminate and use) occur with adequate

quality. The analysis of the tasks performed at the

meetings followed the SECI model (Nonaka &

Takeuchi, 1997) to verify the occurrences of

knowledge conversion and its implications to inform

design of ICVE.

The various tasks and activities performed, and

the procedures regarding the flow of information

during the meetings allowed for knowledge

conversion to occur, both from tacit to explicit and

from explicit to tacit knowledge, demonstrating that

there was KC within the CP. Thus, were able to

identify, for each step of the information flow

process, some requirements to inform the design of

ICVE:

Collection: tools for communication among

different actors/profiles, as well as tools for

linguistic support (e.g. dictionaries, translators);

Storage: record of the information exchanged,

and of the results of the interaction (e.g. results

from discussion, results from a task etc.);

Dissemination: tools for communication and

content and artifact availability. Use of adequate

forms to present information to the Deaf (i.e.

videos, sign writing);

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

210

Analysis: tools to promote discussion and

decision-making (e.g. forums, voting etc.);

Adequate identification of the current speaker, to

allow perception, tracking and intervention,

when necessary; adequate visibility of the

interpreter;

Use: support to perception so that all the

information in the environment (e.g. instructions,

artifact, contents, etc.) is useful.

Table 2 presents the actions that occurred in each

step of the process of information flow, their

analysis, and their relations to the SECI model.

Table 2: Actions in CP and their relation to KC.

Process / Actions –

Ocorrences in CP

SECI Model

Collection/experience

exchange about Libras, Deaf

culture and phonology

Direct experience,

Socialization.

Storage/Record of signs in

Libras and their parameters;

vídeo of the sign execution

and the meetings.

Transfer and storage of tacit

and explicit knowledge,

Socialization and

Combination.

Dissemination/Introduction

and instructions; explanations

abou the phonological modelo

f Libras.

Articulation of tacit

knowledge,

Externalization.

Analysis and Use/

Information translation; sign

identification for each

parameter of the phonology;

review of the vídeo for

disambiguation and

description of the signs.

Tacit and explicit

knowledge are systematized,

articulated and applied,

Externalization,

Combination and

Internalization.

4.2.2 Acts of Speech and Conversation

Organization

According to de Souza (2005), the user intention and

the resulting effects of the use of the language have

a considerable degree of relevance to

communication. Myers (2002) adds that the analysis

of conversations help to understand how the

participants use language to organize the interaction

from moment to moment. This research combines

semiotics and ethnography to try to identify the role

the action of language plays in the coordination in

collaborative meetings. The main findings regarding

the Acts of Speech Analysis indicate its frequent

use to aid communication and coordination in the

CP’s collaborative environment. The modulators,

principles and maxims were used to support problem

solving and to allow the achievement of the goals of

the meetings.

The researchers frequently used Directives, with

Tact in order to encourage the members of the CP to

cooperate, by pointing out the benefits for the Deaf

community the results would bring. The researchers

also used Assertives with Consensus to strength the

cooperation commitment among participants; and

with Modesty to emphasize the researcher’s basic

knowledge in SL and Deaf culture. The use of

Comissives with Generosity served the purpose of

showing how the results would benefit the Deaf

community, and to demonstrate the commitment of

the researchers in the use of the knowledge created,

as well as to guarantee the privacy and ethical

issues. In some occasions, the use of Declaratives

guided the participants in the tasks to be performed,

as well as in situations of indecision or impasse. The

interpreter used Expressives in the translation.

The relation of these results in regards to

implications and requirements for Inclusive

Collaborative Virtual Environments (ICVE)

followed the reflections presented by Barbosa

(2006) on how the Acts of Speech should be used to

inform the design of collaborative systems:

Assertives: Storage of what was said, and

storage of the information about the context of

the system in which the communicative act

occurred, for later retrieval;

Directives and Comissives: Mechanisms that

require a response from the listener to record her

intention to pursue or not the course of action in

the communication. Possibility to change the

context of the system (e.g. when a member

commits to perform a task, it creates an

expectation to modify the status of the project in

the future);

Declaratives: Mechanisms to implement and

disseminate the changes;

Expressives: “Treatment of issues such as the

acquisition and maintenance of the user’s trust,

the right to privacy to all members and the

defence mechanisms used by the members”

(Barbosa, 2006, p.3).

According to Barbosa (2006), the storage of context

information is necessary in order to validate the

commitment of the speaker, recording the context in

which the speech was uttered. Such procedure

allows for future retrieval and evaluation of the

speech in different contexts other than that in which

it was uttered.

As for the Conversational Organization, this

research identified the cooperative processes in the

conversational activities and the action of language,

in the way the participants guided their actions and

organized conversation. The methodology defined

for the meetings characterized the type of dialogue:

ConceptualFrameworkforDesignofCollaborativeEnvironments-CultivatingCommunitiesofPracticesforDeaf

Inclusion

211

the interactions were more spontaneous, with little

formalism. However, there were some roles and

functions in the collaboration process.

In the face-to-face communication, members

organize themselves easily via speech, and the

interactions are more clearly perceived. Some

markers were relevant for the organization of turns,

such as a look, a pause, a hesitation, and the end of

an enunciation among others. There occurred also

some correction mechanisms. The corrections took

place between the Deaf members and the interpreter

when there was a disagreement about a sign in

Libras. In this case, when the wrong utterance was

perceived, one participant initiated the correction.

As for the implications of these conversational

aspects to inform the design of an ICVE, the

research was able to observe:

The environment used to provide support to the

CP, heavily based on task execution, caused a

predominant use of questions and answers, of

actions and reactions, thus minimizing the

organizational difficulties of turns and of

interactive sequences in this kind of

environment;

The formalization and implementation of social

protocols may be useful in virtual environments

in order to organize communication (turns and

sequences) and the process of correction in

synchronous interactions;

Conversational agents (intelligent agents) may be

used to indicate the current action (e.g. to show

when the active speaker has completed her turn),

point the next actions, monitor tasks, provide

tips, give support in problem resolution, among

others.

4.2.3 Cooperation Principles

Cooperation means that people need to perform

tasks together in a shared space (be it physical or

virtual). A CP stands to benefit by using Grice’s

(1975) cooperation principles to guide the behavior

or its members to achieve the collaboration goals.

The researchers analyzed Grice’s conversational

maxims (i.e. Quantity, Quality, Relevance and

Manner) as they occurred in the actions performed

during the meetings.

As for the “Quantity”, the information was

considered to be sufficient, given that it allowed for

comprehension and agreement to establish

collaboration. Mostly, there was some information

loss when the interpreter tried to simplify or reduce

the content in order to facilitate communication. But

the group promptly corrects any misunderstanding

by questioning the information given.

The “Quality” of the information was noticed,

and affected communication due to the complexity

of the theme, and the lack of familiarity with the

theme by the participants. Additionally, the

interpreter wasn’t very involved in the Deaf

community, which made communication difficult at

times. This is a clear call for more involvement, and

for tools to mediate and support conversations

between Deaf and non-Deaf people via an interpreter

(e.g. thesaurus, dictionaries).

The information that was imparted to the CP was

within the context of the proposed goal of the CP,

thus making the information “Relevant” to the

discussions and KC. There were some small periods

where the CP lost focus on the tasks to be

performed, but the coordinators where able to bring

the CP back to focus.

The use o Libras, the natural language of the

Deaf, was pivotal for the success of the meetings,

and demonstrated the importance of the use of

“Manner” in such bilingual environments. Libras is

a complete linguistic system, with grammar and

structures, a rich and expressive tool that allowed for

the use of the modulators to emphasize interaction at

communication time, thus supporting coordination

and commitment of the members. The care with

which the physical positioning of the interpreter

within the room was treated paid off, allowing the

communication to flow more easily.

Some of the implications of these observations

about cooperation principles to inform design of

an ICVE are as follows:

Mediators should direct the speech to the

interpreter, but with care that all members of the

group perceive the yielding of turn. Mechanisms

to facilitate perception, which put the focus and

the context on the current speaker, are necessary

to facilitate the comprehension by the Deaf. The

Deaf require to be visually in contact with the

utter.

Differentiation of responsibilities may support

the achievement of goals, in a collaborative

environment. Due to the complexities of the

various actors in an inclusive communication,

there should be more investigation about the

potential of an interaction mediator actor.

Additionally, there should be considered that the

coordination process must not impose rigid rules

to the tasks, in order not to difficult interaction.

The environment should provide mechanisms to

support the decision making process (e.g. survey,

voting mechanisms) when divergences occur (i.e.

when no consensus is reached).

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

212

5 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The proposed conceptual framework aims to inform

the design of ICVE to support CP of Deaf and non-

Deaf members. This section presents the schema of

the necessary elements for accessibility, inclusion

and the adequate participation of all members in

such collaboration environment.

5.1 Preliminary Model

The proposed conceptual framework is based on the

ontology to support CP presented by Tifous et al.

(2007). The original ontology is robust and contains

several elements and relations inherent in a CP. The

proposed framework extends the ontology with new

variables and relations that were identified in the

ethnographic study presented on section 4. The

remainder of this section presents the new variables:

Members, Competence, Collaboration and

Resources of the CP:

Members:

Special Needs: members of a CP may have

special needs that should be adequately

addressed. In the case of the proposed

framework, these needs for the environment

mostly refer to the inclusive character associated

with the inclusion of Deaf people.

Competences:

Presentation Forms: It is necessary to better

characterize the forms of information recording and

presentation (i.e. videos in Libras, sign writing,

images, symbols etc.).

Information Structure: The structure and

organization of the information that is the object of

study by the CP should be such that they facilitate

storage, retrieval and knowledge acquisition.

Collaboration:

Events: Collaboration involves the organization

of events that may include the entire CP or

specific groups, depending on the context, the

activities and tasks to be performed and the

needs of the environment (e.g. video conference

are more adequate, since they allow for visual

communication).

Communication Mediation: The active

participation of an interpreter is necessary to

guarantee communication between Deaf and

non-Deaf.

Social Protocol: Social protocols (de Souza,

2005) are important in collaborative

environments, to aid participants to organize and

coordinate their actions (as opposed to rigid

systems and formal coordination).

Conversational Agents: Mechanisms to

diagnose actions and to interact with users.

Conversational agents may be used as marker in

the organization of who has the turn to speak.

Responsibilities: Different participants, with

different profiles and roles have responsibilities

that determine the form in which the CP is

coordinated. Those responsibilities should be

well defined and respected. The mediator, for

example, should guide and promote interaction

and collaboration.

Resources or the CP:

Linguistic Support Tools: Tools to support

communication that address the needs of the CP:

dictionaries in SL, translators, transcription

systems etc.

Tools for COOPERATION: The cooperation

may involve activities to be performed together

by different people on the same resource (e.g.

editing of a text). This simultaneous use requires

cooperative editors and version control systems.

In a CP where members share, point, write,

dramatize on a shared document, such editors

and video resources are necessary.

Figure 1 presents the preliminary proposed

framework with its extensions on the ontology

(Tifous et al., 2007). The new variables incorporated

into the original ontology are presented in a different

color (green). The model is characterized as domain

ontology: it describes concepts of a specific domain

of knowledge, with their properties and restrictions.

The model is presented as a means to facilitate

knowledge representation about CP. Next, this

article will present the structural and behavioral

models of the proposed framework.

5.2 Structure and Behavior

This research reuses the knowledge from ontologies

to derive the structural and behavioral models of the

proposed framework, according to the theories of

Martins (2009). The knowledge about the tasks was

captured from the preliminary model. The following

procedures were used: i) identification of the tasks

from the domain ontology; ii) decomposition of each

task; and iii) identification of the roles involved in

performing the tasks. Table 3 presents the

knowledge about the tasks.

As seen in Table 3, an entity plays a role to solve

problem. A role or roles were identified for the

performance of each task. The main tasks were

ConceptualFrameworkforDesignofCollaborativeEnvironments-CultivatingCommunitiesofPracticesforDeaf

Inclusion

213

identified and decomposed into sub-tasks, necessary

in order to achieve the goals of the CP.

Figure 1: Preliminary proposed framework.

The diagrams that represent the behavioral and

structural model of the proposed framework were

derived from the domain knowledge for the CP and

the tasks. Figure 2 presents a state diagram for a

videoconference that illustrates the scenario of

speech turn in the form of “one speaker at a time”.

Such diagram demonstrates the significant aspects

needed for the inclusion of the Deaf.

A videoconference between Deaf and non-Deaf

may require an automatic translator, or an

interpreter, to mediate communication. In so far,

there is a lack of automatic translators. Thus, the

interpreter is crucial in the process. Figure 2

emphasizes the behavior of “taking turns to speak”.

It shows the sub-unit of the conversation where each

member speaks alone in her turn, and the interpreter

translates each speech.

Figure 2: State Diagram – Example of taking turns “Each

speaker at a time.

This roundabout form of communication (i.e. the

speakers take turns, the other participants wait for

that speaker to end her turn, and then all the

members have access to the a turn to speak) was

used. The changing of turns may be delimitated by a

linguistic or paralinguistic marker (e.g. pause,

hesitation, hand movement etc.). After the

translation, that marks a transition of turn, the next

speaker may gain the turn by self-choice.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This research provides support for the needs of the

Deaf community by proposing a framework to

inform the design of ICVE for CP that provides

equal opportunities for the Deaf in all areas of

knowledge. The CP enhance the interaction

expectations, allowing the Deaf to converse and to

comprehend reality surrounding her, the reality of

other persons, allowing the Deaf to share

information and experiences, in order to create

knowledge and to develop her potentials.

The literature review provided a theoretical

background with which the researchers were able to

delimitate the necessary aspects for collaboration

within a CP, as well as to verify the (lack of) tools

for the Deaf and their limitations. The ethnographic

study used such background to identify the actual

aspects involved in a collaboration environment

comprised of Dear and non-Deaf within a CP.

The development of the proposed framework to

inform design of ICVE allowed the researchers to

identify some special characteristics: linguistic

support tools are necessary in order to cultivate such

CP (e.g. dictionaries in SL, translators, transcription

systems, interpreters etc.); a module for the

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

214

interpreter to mediate communication; several ways

to present information (videos in SL, sign writing

system); adequate mechanisms for perception (the

Deaf need strong visual mechanisms to point

attention towards the current speaker); support to

establish roles and responsibilities as a way to make

collaboration possible; mechanisms to structure

information for later retrieval and use, for

information acquisition and knowledge creation;

coordination mechanisms such as social protocols

and conversational agents to guide communication.

Future works include the validation of the

framework in the design of an ICVE.

REFERENCES

Almeida, L. D. A., 2011. Awareness do espaço de

trabalho em ambientes colaborativos inclusivos na

Web. Ph.D. thesis, Instituto de Computação,

Universidade Estadual de Campinas.

Austin, J.L., 1962. How to Do Things with Words.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, London.

Barbosa, C. M. A., 2006. Manas - uma ferramenta

epistêmica de apoio ao projeto da comunicação em

sistemas colaborativos. Ph.D. thesis, Departamento de

Informática, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio

de Janeiro, p.1-222.

Bukowitz, W. R., Williams, R. L., 2002. Manual de gestão

do conhecimento. Bookman, Porto Alegre.

Carroll, J. M., et al., 2003. Knowledge management

support for teachers. Educational Technology

Research and Development, 51(4), p. 42-64.

de Souza, C. S., 2005. The semiotic engineering of human

computer interaction. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT

Press.

Deaudelin, C., Nault, T., 2003. Collaborer pour apprendre

et faire apprendre – La place des outils

technologiques. Presses de l'Université du Québec.

Fernandes, S., 2006. Avaliação em Língua Portuguesa

para Alunos Surdos: Algumas considerações.

SEED/SUED/DEE, Curitiba.

Garfinkel, H., 1967. Studies in ethnomethodology.

Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Grice, H. P., 1975. Logic and conversation. In: Cole, P,

Morgan, J. (Eds.) Syntax and Semantics, New York:

Academic Press, v.3: Speech Acts.

Langelier, L., Wenger, E. (eds.), 2005. Work, Learning

and Networked, Québec: Cefrio.

Lave, J., Wenger, E., 1991. Situated learning: Legitimate

peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge

University Press.

Mantoan, M.T.E., 2005. Inclusão é o Privilégio de

Conviver com as Diferenças. In Nova Escola, maio.

Marcuschi, L. A., 2003. Análise da conversação. 5ª

Edição. Editora Ática, São Paulo.

Martins, A. F., 2009. Construção de Ontologias de Tarefas

e sua Reutilização na Engenharia de Requisitos. Tese

de Mestrado, Espírito Santo: UFES.

Miller, G. A., 1995. WordNet: a lexical database for

English. Commun. ACM 38(11), p. 39-41.

Myers, G., 2002. Análise da Conversação e da Fala, In

Bauer, Martin W. & Gaskell, George (org.). Pesquisa

Qualitativa com Texto, Imagem e Som: Um Manual

Prático. Petrópolis: Vozes.

Nielsen, J., 1996. Multimedia and Hypermedia – The

Internet and Beyond, Academic Press Inc.

Nonaka, I., Takeuchi, H., Criação do Conhecimento na

Empresa. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, (13), 1997.

Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., Jefferson, G., 1974. A

simplest systematics for the organization of turn-

taking for conversation. Language, pp. 696-735.

Santana, R.C.G., Santos, P.L.V. A. C., 2002 Transferência

da Informação: análise para valoração de unidades de

conhecimento. Datagramazero, v.3, n.2.

Searle, J.R., 1969. Speech Acts: an essay in the philosophy

of language. Cambridge: University Press.

Searle, J.R., 1979. Expression and Meaning. Studies in the

Theory of Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Shneiderman, B., 1998. Designing the user interface:

strategies for effective human-computer interaction.

Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

Silva, A., 2010. Da Aprendizagem Colaborativa às

Comunidades de Prática. Universidade Aberta, 2010.

Takeuchi, H. E Nonaka, I., 2008. Criação e dialética do

conhecimento. Gestão do conhecimento. Porto Alegre:

Bookman.

Tifous, A., Ghali, A.E., Dieng-Kuntz, R., Giboin, A.,

Evangelou, C., Vidou, G., 2007. An ontology for

supporting communities of practice. In K-CAP 39-4.

Trindade et al., 2011. Communication and Cooperation

PragmatismL an analysis of a Community of Practice

to Study Sign Language. WSKS. Mykonos, Greece.

Vidou, G., Dieng-Kuntz, R., El Ghali, A., Evangelou, C.,

Giboin, A., Tifous, A. and Jacquemart, S. 2006.

Towards an Ontology for Knowledge Management in

Communities of Practice. PAKM’06, p. 303-314.

Weiseth, P. E., Munkvold, B. E., Tvedte, B., Larsen, S.,

2006. The Wheel of Collaboration Tools: A Typology

for Analysis within a Holistic Framework.

CSCW’2006, Banff, Canada, p. 239-248.

Wenger, E., 2004. Knowledge Management as a

Doughnut: Shaping your knowledge strategy through

communities of practice. Ivey Business Journal, 68(3).

Wenger, E., 2010. Communities of practice and social

learning systems: the career of a concept. Social

Learning Systems and Communities of Practice.

Springer, Dordrecht, Chapter 11 in Blackmore, p.179.

ConceptualFrameworkforDesignofCollaborativeEnvironments-CultivatingCommunitiesofPracticesforDeaf

Inclusion

215