Modeling the Creation of a Learning Organization by using the

Learning Organization Atlas Framework

Mijalce Santa

1,2

and Selmin Nurcan

2

1

Faculty of Economics – Skopje, Ss Cyril and Methodius University, Blvd Goce Delcev 9V, Skopje, Macedonia

2

Centre de Recherche en Informatique, Université Paris I – Panthéon Sorbonne, 90 rue de Tolbiac, Paris, France

Keywords: Learning Organization Atlas Framework, Learning Organization Grid, Learning Organization Road Map,

Dynamic Model.

Abstract: In a continuously changing external environment, the learning organization can provide a competitive

advantage. However, the concept has been largely criticized for the lack of guidelines and tools on how it

could be developed. This undermines the opportunity for the development of the learning organization. This

paper aims to contribute toward the debate on its creation by proposing a Learning Organization Atlas

Framework approach. This framework comprises of the facets of the learning organization that characterize

them, a Learning Organization Grid for the analysis and benchmarking of organizations, a Learning

Organization Atlas that can be used for developing models of them, and a Learning Organization Road Map

that includes the intentions of the organization and the strategies to achieve those intentions. With the

framework and its four elements, we propose a method for modeling the learning organization and

organizational change by providing embedded flexibility. The next level for research is in identifying the

influence between different facets, strategy selection, and development of guidelines for models of learning

organizations.

1 INTRODUCTION

A learning organization is an organization that

facilitates the learning of all its members and

consciously transforms itself and its context (Pedler

et al., 1991). It is an organization skilled at creating,

acquiring, interpreting, transferring, and retaining

knowledge, and at purposefully modifying its

behavior to reflect new knowledge and insights

(Garvin, 2000). In today’s complex external and

internal environments, where vital planning

assumptions continuously change, the learning

organization is seen as a way in which the

organizations sustain their competitiveness

(Jashapara, 2004).

According to The Boston Consulting Group, in a

world driven by innovation and rapid change,

becoming a learning organization from top to bottom

provides a clear competitive advantage and this will

become more important in the future (2008; 2010).

A survey by the business magazine

“Strategy+business” (Kleiner, 2005) ranked the idea

of "the Learning Organization" as the second most

enduring idea about strategy and business, among

the 10 ideas that are most likely to last at least

another 10 years.

Though the positive values of learning

organizations, such as increased competitiveness

have been widely discussed, critical aspects have

also been raised, particularly the dilemmas related to

its creation.

These criticisms are justified as until now only a

limited understanding of how organizations can

accomplish this exists and even less is available in

terms of ideas supported by empirical research

(Davis and Daley, 2008; Easterby-Smith et al., 1999;

Tsang, 1997), and further, no practical operational

advice (Garvin, 2000) or a template (Cavaleri, 2008)

that managers can use is available.

Therefore, the mismatch between the strong

expression of importance and need for learning

organizations and the lack of capabilities,

knowledge, and paths on how to create them

strongly undermines the idea and its application.

This paper aims to fill this gap. The purpose of the

paper is to a) present a multilevel and multifaceted

framework for the dynamic development of the

learning organization and b) apply this framework

278

Santa M. and Nurcan S..

Modeling the Creation of a Learning Organization by using the Learning Organization Atlas Framework.

DOI: 10.5220/0004450102780285

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 278-285

ISBN: 978-989-8565-60-0

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

on an example organization.

In the first part, the existing models on a learning

organization are presented and discussed. Then, we

present the Learning Organization Atlas Framework

and show how the learning organization models can

be developed and applied. We apply the framework

and the modelling approach on an example

organization. Finally, a conclusion and some

perspectives on this work are presented.

2 RELATED WORK

The most known models in the learning organization

literature are the energy flow model (Pedler et al.,

1991), Senge's model (Senge, 1990), seven

dimensions of the learning organization (Watkins

and Marsick, 1993), and learning organization

building blocks (Garvin et al., 2008). All these

models are normative and suggest that learning can

occur only under certain conditions. The leaders and

the organization need to create those conditions

through disciplined action or intervention. If the

organization does not meet these conditions, it

cannot learn.

Pedler et al. (1991) focus their model on

movement and identify flows that can move: a)

vertically from an individual to the collective and

vice versa linking ideas and policy and b)

horizontally from vision to action and vice versa

linking actions and operations. These flows are

supported by eleven characteristics that create the

learning organization:

The learning approach to strategy

Participative policy making

Informating

Formative accounting and control

Internal exchange

Reward flexibility

Enabling structures

Boundary workers as environment scanners

Inter-company learning

Learning climate

Self-development opportunities for all

Although this model tries to have an integrated

approach toward the learning organization, it cannot

be used for its development. The main shortcoming

of this model is that it neither defines the relations

between the elements nor on how the interactions

between the flows should be done.

Senge (1990) identified five elements that are

important for the learning organization: building a

shared vision, personal mastery, working with

mental models, team learning, and systems thinking.

He does not structure the elements in a model and

does not provide a clear picture on the relations

between these elements. A characteristic of this

model is that it introduces systemic thinking to the

learning organization and identifies it as an element

that underlies all the other elements.

Through the seven dimensions of the learning

organization model, Watkins and Marsick (1993)

view it as one that has the capacity to integrate

people and structures in order to move toward

continuous learning and change (Yang et al., 2004).

The model is structured around four levels:

individual, teams, organization, and society. For

each level, they identified seven distinct but

interrelated dimensions of a learning organization:

Continuous learning

Inquiry and dialogue

Team learning

Empowerment

Embedded systems

Systems connection and

Strategic leadership

This model is clearly organized and structured.

However, two shortcomings are identified. First, a

lack of the developmental aspect that presents the

levels that these dimensions can have, and second, a

lack of clear identification of the organizational and

team dimensions on the individual dimensions.

The learning organization building blocks model

has identified three blocks that support the

development of the learning organization:

a supportive learning environment that

consists of psychological safety, appreciation

of differences and openness to new ideas, and

time for reflection,

concrete learning processes and practices

consisting of experimentation, information

collection, analysis, education and training,

and information transfer, and

leadership that reinforces learning.

This model does not identify the levels in the

learning organization and lacks identification of the

influence of all the blocks on the individual who is

learning in the organization.

In Table 1, a comparative overview of the

models is presented (1 is low, 5 is high). The

comparison is based on the number of facets that are

included in the models, levels of development of the

facets, identification of the relations between the

facets and the possibility to use the model for LO

development. Overall the table presents that the

ModelingtheCreationofaLearningOrganizationbyusingtheLearningOrganizationAtlasFramework

279

existing models provide rather poor base for

mapping and developing the learning organization.

Table 1: Evaluation of the models.

Authors Domains Levels Relations Develop

Pedler et al., (1991) 4 1 1 1

Senge, (1990) 3 2 3 2

Watkins and

Marsick, (1993)

3 4 3 2

Garvin et al., (2008) 3 2 3 2

According to (DiBella, 1995), there are two

other perspectives to the learning organization:

developmental and capability. The developmental

perspective sees a learning organization as a stage in

the organization's development. There are different

styles and processes for different stage. Although

this perspective provides more flexibility in

becoming a learning organization, it does not

identify that the learning is indigenous to

organizational life. The capability perspective

proposes that each organization learns through its

own learning processes embedded in the

organization's culture and structure.

The capabilities perspective legitimates a

pluralistic view toward learning and learning style

(DiBella, 1995) and provides the flexibility in the

organization to create its own path toward becoming

a learning organization.

The three perspectives, although conflicting in

some aspects, when combined with each contribute

to the understanding of the learning organization

(DiBella, 1995). The normative perspective provides

the vision that serves as focal point or target for

change. The developmental perspective considers

the history and shows how learning is contingent on

the organization's stage of development. The

capability perspective uncovers the transparency of

the present.

Although it can be expected that there are clear

guidelines on how to organize the process of

creating the learning organization, it is not the case.

Only some books provide a step-by-step guideline

(Kline and Saunders, 2010; Marquardt, 1996; Pearn

et al., 1994) but that is more related to change

management than to a learning organization. A

different approach is used by King (2001) who

proposes six distinctly different strategies through

which the learning organization can be achieved:

Information systems infrastructure

Intellectual property

Individual learning

Organizational learning

Knowledge management

Innovation

As King notes none of these strategies, if applied

alone, is sufficient. There is a need for their

combination.

3 LEARNING ORGANIZATION

ATLAS FRAMEWORK

In order to develop a dynamic model that will enable

the creation of the learning organization the

following aspects should be taken into account.

First, the learning organization is a multi-faceted

construct (Yang et al., 2004). It has too many facets,

attributes, and variables that need to be taken into

account. Second, the relationships within the facet

and between the facets are complex and determine

how the learning organization will be developed

(Grieves, 2008). Third, the learning organization is a

chameleon-like target (DiBella, 1995), it is not a

state that can be achieved, but a continuous journey,

a journey on which the organization will

continuously learn and change to stay on the edge of

chaos (Waldrop, 1992). Fourth, there is no single

approach to build a learning organization because

each approach should be customized by taking into

account the characteristics of the individual

organization (Redding, 1997). Taking in account

these aspects, we propose the Learning Organization

Atlas Framework that consists of four elements:

Learning Organization Facets, Learning

Organization Grid, Learning Organization Atlas, and

Learning Organization Road Map. This framework

with its elements provides a systematic way of

dealing with learning organization modeling and

organizational change by providing embedded

flexibility.

3.1 Learning Organization Facets

Through an extensive literature review, eleven facets

of the learning organization were identified. The

learning facet is identified as a core facet, while the

others are distributed to four pillars that support the

learning in the organizations.

Direction pillar – vision and strategy

Infrastructure pillar – structure, technology,

and processes

Informal pillar – culture, power, and politics

Change pillar – change and leadership

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

280

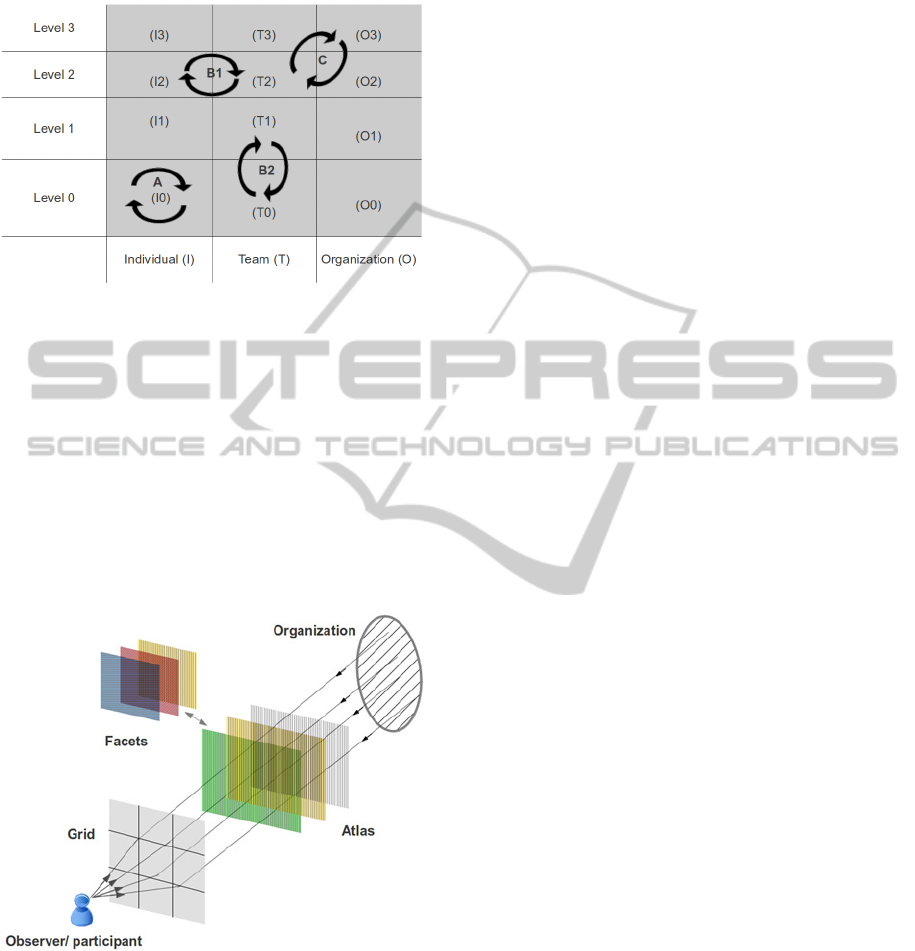

3.2 Learning Organization Grid

Each facet is looked through a Learning

Organization Grid (LOG) that is a result of the

combination of the learning entities in the

organization and the levels of learning. We have

identified three entities (individual, team, and

organization) and four levels of learning (zero, one,

two, and three). The entities and the levels of

learning are identified through an extensive

literature review and are a summary of the work of

different authors (Senge, 1990; Marsick and

Watkins, 1993, Pedler et al., 1991; Argyris, 1999).

On an individual level

Zero learning – receipt of information which

may lead to learning, but are not learning

events

Learning level 1 – skill learning, that is,

making choices within a simple set of

alternatives. Also known as single-loop

learning (Argyris, 1999), or adaptive learning

(Senge, 1990).

Learning level 2 – choosing between sets

within which level 1 learning takes place.

Also known as double-loop learning (Argyris,

1999), or generative learning (Senge, 1990).

Learning level 3 – learning to learn, also

known as deutero-learning (Argyris, 1999).

For each individual level of learning, an

appropriate team and organization level should be

identified. On a team level the following type of

teams are identified:

Meet – the teams only meet and exchange

information for mere reporting purpose with

no goal to support learning

Discuss – the team members try to tell and sell

their opinion and to gain opinion on one

meaning.

Dialogue – to inquire, learn, unfold shared

meaning, and uncover and examine

assumptions.

Integrate – to integrate multiple perspectives

and to jointly create new perspectives.

On an organizational level, we have the

following levels:

Waste – the organization is not recognizing

the knowledge it has or the need to manage

that knowledge.

Store – the organization is collecting the

information and knowledge that is circulating

in the organization and stores it in various

ways. Limited distribution of this knowledge

is available to the teams and individuals.

Disseminate – the collected knowledge is

made available to teams and individuals in

various ways and it can be easily used in their

learning.

Create – the organization is creating new

knowledge that it provides to the individuals

and teams in the organization.

Figure 1: Learning organization grid applied on the

learning facet.

Figure 1 presents the result we get when we look on

the learning facet through the LOG and Figure 2 for

the technology facet.

Figure 2: Learning organization grid applied on the

technology facet.

Each grid results in nine cells per facet. We have

identified four types of relations between the cells

(Figure 3):

intra-cell (A) that could initiate translational

change,

intra-level (B1 and B2) where B1 initiates

translational, while B2 transformational

change,

inter-level (C) initiates transformational

change, and

inter-grid are the relations between the cells of

different facets. All the previous relations are

ModelingtheCreationofaLearningOrganizationbyusingtheLearningOrganizationAtlasFramework

281

a part of this type of relation and can result in

translational and transformational changes.

Figure 3: Relations within the Learning Grid.

3.3 Learning Organization Atlas

The LOG enables us to create a map of each

Learning Organization Facet that it is identified.

However, the facets are interrelated and influence

each other so that the real value is achieved when

the maps are layered on each other and the relations

are identified. Depending on the purpose of the

research, all or some of the maps can be layered. To

achieve this, we will use the Learning Organization

Atlas (LOA) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The Learning Organization Atlas.

By layering facet maps created with the same grid

through the LOA, the following can be achieved:

identify how the cells within an individual

facet are aligned and what needs to be

changed,

identify how different facets are aligned and

based on that, make decisions on what needs

to be changed in order to become a learning

organization, and

the organizations can create a customized

learning-organization atlas model that will fit

their characteristics and needs.

To facilitate the process of making decisions and

taking steps for changing the organization and

making a customized learning organization model

the organization can use the Learning Organization

Road Map.

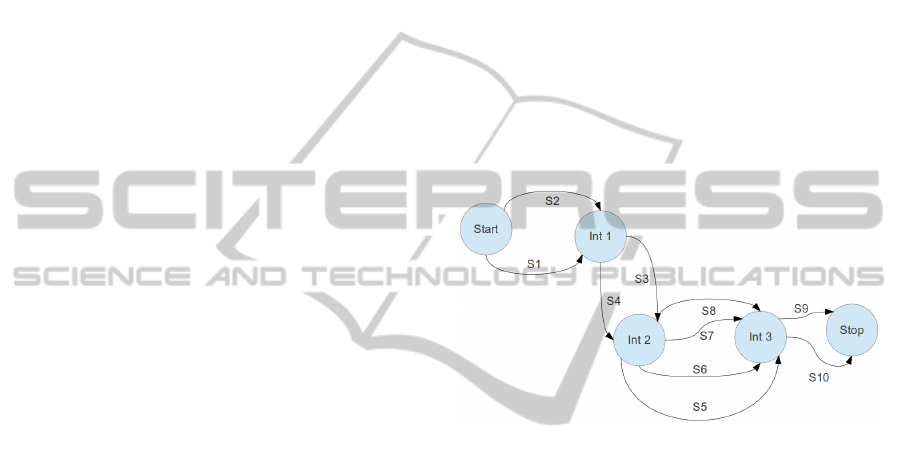

3.4 Learning Organization Road Map

In reality, an organization is a dynamic entity that is

changing continuously. Organizations need to have

tools that will help them to change and sustain this

competitiveness. The Learning Organization Road

Map (LORM) based on results of the LOA provides

guidelines to the organizations, their learning needs,

and the required changes to be made. LORM is built

on the propositions made by the map model of

Rolland et al. (1999). According to them, a map is a

process model in which a non-deterministic ordering

of intentions and strategies has been included. The

map is composed of one or more sections (Rolland

and Prakash, 2001). A section is an aggregation of

two kinds of intentions, the source and target

intentions together with a strategy represented as <

source intention Ii, target intention Ij, strategy Sij>.

An intention is a goal that can be achieved by the

performance of a process. There are two special

intentions, Start and Stop, to begin and end the map

respectively. A strategy is an approach, a manner to

achieve an intention. It characterizes the flow from Ii

to Ij and the way Ij can be achieved. Because the

next intention and strategy to achieve it are selected

dynamically, guidelines that make available all

choices open to handle a given situation are of great

importance. The map has three guidelines,

‘Intention Selection Guideline’ per node Ii,

except for Stop. Given an intention Ii, an

Intention Selection Guideline (ISG), identifies

the set of intentions {Ij} that can be achieved

in the next step

‘Strategy Selection Guideline’ per node pair

<Ii,Ij>. Given two Intentions Ii, Ij, and a set of

possible strategies Sij1, Sij2, ..Sijn applicable

to Ij, the role of the Strategy Selection

Guideline (SSG) is to guide the selection of a

Sijk.

‘Intention Achievement Guideline’ per section

<Ii,Ij, Sij>. Intention Achievement Guideline

(IAG) that provides an operational or an

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

282

intentional means to fulfill a business

intention.

Each map is represented as a directed graph from

Start to Stop. In the graph, the intentions are

represented as nodes and strategies as edges between

these. The graph is directed because the strategy

shows the flow from the source to the target

intention.

4 APPLICATION

In this section, we illustrate the process of

development of a dynamic model of the learning

organization. Organization X pressed by competition

and a changing environment decides to fulfill the

learning organization requirements and to be on

level 3 cells for each entity on each facet. To achieve

this it first needs to analyze the existing situation in

the organization, benchmark the results to the

learning organization characteristics, and then to

align the cells in the facets and between the facets to

fulfill the learning organization (LO) requirements.

Based on the above, the intentions are:

Intention 1 – analyze the facets

Intention 2 – align the facets

Intention 3 – fulfill LO requirements

To achieve intention 1 the organization can use

formal (S1) or informal strategy (S2). By formally

applying the LOG and defining the processes

through which the information will be collected, it

can be expected that Intention 2 will be achieved.

However, a strategy that is more informal can be

used to get an introductory view of the position of

the organization X.

To move from intention 1 to intention 2, the

organization can apply two strategies: align

cells within a facet (S3) or/and align cells

between the different facets (S4). These

strategies are based on the identified

relationships within the LOG and LOGs of

different facets.

To move from intention 2 to intention 3, the

organization can apply four strategies:

transformational (S5), incremental (S6),

supported from outside (S7), and internally

managed (S8). Strategies S5 and S6 are based

on the type of changes that are required to

move the organization from one cell to the

next level of cell. Strategy S8 is based on

literature review, where it is suggested that in

the process of becoming a learning

organization an external expert with

knowledge and practical experience of a

learning organization should be involved. S8

is proposed in order to give flexibility to the

organization to develop into a learning

organization with its own resources.

After the realization of intention 3, the

company can apply a strategy of keeping the

new status (S9) or keeping the company open

for change (S10). The learning organization is

a continuous journey, so S10 should provide a

way for this to be achieved. On the other hand,

S9 can be used when there are no new internal

or external pressures to make new changes in

order to stay as a learning organization.

All these relations are presented in the global

map (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Learning organization <source intention Ii, target

intention Ij, strategy Sij>.

To achieve intention 1, we opt for strategy 2 and

use the LOG on the learning and technology facet

presented in Figures 1 and 2. The following have

been identified for the learning facet: The

individuals are practicing adaptive learning and as a

result, they make choices within a simple set of

alternatives (cell I1). The teams exist but they only

meet and exchange information for a mere reporting

purpose with no goal to support learning (cell T0).

The organization is collecting the information and

knowledge that is circulating in the organization and

stores it in various ways. However, limited

distribution of this knowledge is available to the

teams and individuals (O1).

Regarding the technology facet, the analysis

reveals that the majority of the individuals in the

organization have computers on which they mainly

use the internet browser, email application, and

office package (I0). The teams have bulletin boards,

forums, and some team tools (T1); however, the

majority of team members only read the

information, while only a small number of persons

ModelingtheCreationofaLearningOrganizationbyusingtheLearningOrganizationAtlasFramework

283

publish on it. On the organizational level, the

organization uses the email system for

communication within the company (O0).

By using the LOA, we can identify that

Organization X is not fulfilling the principles of the

LO (at level 3). Furthermore, there is misalignment

between the cells within both facets.

One important aspect of using the LORM is that

the global map can be decomposed in refined maps

that will show the intentions and strategies at a more

detailed level, for example, for the section <Analyze

the facets, Align Facets, Align cells within a facet

strategy>. The refined map for the learning facet is

presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Refined map.

The following intentions were identified:

Intention 1 - vertical alignment of each entity

to be on level 3; and

Intention 2 - horizontal alignment of each

entity to be on the same level.

Strategies for vertical alignment are divided as per

the entity:

Strategies for individuals:

Informal learning (S1.1) that includes learning

at work and action learning; and

Formal learning (S1.2) that is based on

trainings and formal courses.

Strategies for teams:

Formal training for work in teams (S1.3); and

Team competition (S1.4) that is based on

same teams working on same issues and

creating redundancy (Nonaka, 1994).

Strategies for the organization:

Developing formal systems (S1.5) for

collecting, storing, and distributing

information and knowledge; and

Developing informal systems (S1.6) for

collecting, storing, and distributing

information and knowledge (Pedler et al.,

1991; Watkins and Marsick, 1993).

The strategies for horizontal alignment are:

Anticipation strategy (S1.7) based on the

perception of the organization that a certain

entity is underperforming in certain facets and

self-initiating the changes in that facet; and

Push strategy (S1.8) were the organization has

not self-initiated the changes, but now, owing

to incompatibility with other facets the

organization cannot function properly and it is

pushed to change.

Based on the selection of the strategies the

process will be ended with:

Formal proposal for action (S1.9).

By developing a refined map for each section,

we create a detailed road map that the organization

can use to develop a customized and own approach

in becoming a learning organization. The map can

be refined up to a level of business processes,

wherein a business process chunk is developed. The

business process chunk will specify the roles, actors,

and their activities through which the strategies can

be realized and intentions achieved.

By using an intention-driven model, it is easier

to highlight the business intentions and strategies.

Furthermore, the road map model provides a priori

flexibility since the navigation will be dynamically

performed during the execution.

5 CONCLUSIONS

In this paper, we have proposed the Learning

Organization Atlas Framework as a modelling

approach for the LO. We have proposed a Learning

Organization Grid that can be used for analyzing and

benchmarking organizations toward the Learning

Organization Facets. Then, we presented the

Learning Organization Atlas, which can be used to

develop learning organization models. In the next

section, we introduced the Learning Organization

Road Map as an intentional model of the learning

organization. Through it, we demonstrated the

flexibility with which the learning organization can

be developed based on the business intentions and

the strategies that the organizations can use. At the

end, we presented an example of how all the three

elements can be used to develop a LO.

A major advantage of our proposed approach is

the systematic way of dealing with learning

organization modelling and organizational change.

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

284

Furthermore, it has an embedded flexibility that

enables it to be used for development of tools and

information systems for different organizations by

type and size. When compared with the other models

(Table 1) LOAF provides better ground for

developing the Learning organization because it:

Enables the organizations to include more

facets in their analysis (11 in total) or add

other facets not identified here.

Clearly identify the levels that are important

for analysis of the facets.

Creates a structure through which in a more

clear way the facets relations and development

paths can be identified and justified.

For the future, we have identified three avenues

for research. First, the identification of the influence

between cells in the same facet and the influence of

one facet on the other facets. Second, adding

identification of which strategies can be best utilized

to achieve the goal of becoming a LO. Third, the

development of clear guidelines, that support the

selection of intentions and strategies, and the

achievement of those strategies. By researching in

these three areas, our proposed approach can be

strengthened and applied to more organizations

REFERENCES

Argyris, C., 1999. On Organizational Learning, Wiley-

Blackwell., 2nd ed.

Cavaleri, S. A., 2008. Are learning organizations

pragmatic? The Learning Organization 15, 474–485.

Davis, D., Daley, B. J., 2008. The learning organization

and its dimensions as key factors in firms’

performance. Human Resource Development

International 11, 51–66.

DiBella, A. J., 1995. Developing learning organizations: A

matter of perspective. Academy of Management

Journal 38, 287–290.

Easterby-Smith, M., Araujo, L., Burgoyne, J., 1999.

Organizational Learning and the Learning

Organization: Developments in Theory and Practice,

Sage Publications Ltd., 1st ed.

Garvin, D. A., 2000. Learning in Action: A Guide to

Putting the Learning Organization to Work. Harvard

Business Press.

Garvin, D. A., Edmondson, A. C., Gino, F., 2008. Is yours

a learning organization? Harvard Business Review 86,

109.

Grieves, J., 2008. Why we should abandon the idea of the

learning organization. The Learning Organization 15,

463 – 473.

Jashapara, A., 1993. The competitive learning

organization: A quest for the Holy. Management

Decision 31, 52.

Jashapara, A., 2004. Knowledge Management: An

Integrated Approach. Pearson Education Limited,

Essex.

King, W. R., 2001. Strategies for creating a learning

organization. Information Systems Management 18, 12.

Kleiner, A., 2005. Our 10 Most Enduring Ideas.

strategy+business Winter 2005.

Kline, P., Saunders, B., 2010. Ten Steps to a Learning

Organization, Great River Books., 2nd ed.

Marquardt, M. J., 1996. Building the Learning

Organization: A Systems Approach to Quantum

Improvement and Global Success. Mcgraw-Hill.

Marsick, V. J., Watkins, K. E., 2003. Demonstrating the

Value of an Organization’s Learning Culture: The

Dimensions of the Learning Organization

Questionnaire. Advances in Developing Human

Resources 5, 132–151.

Nonaka, I., 1994. A Dynamic Theory of Organizational

Knowledge Creation. Organization Science, 5(1),

pp.14–37.

Örtenblad, A., 2007. Senge’s many faces: problem or

opportunity? Learning Organization, The 14, 108–122.

Pearn, M., Wood, R., Fullerton, J., Roderick, C., 1994.

Becoming a learning organization: how to as well as

why, in: Towards the Learning Company: Concepts

and Practices. McGraw-Hill, pp. 186–199.

Pedler, M., Burgoyne, J., Boydell, T., 1991. The Learning

Company: A Strategy for Sustainable Development,

McGraw-Hill Publishing Co., 1st ed.

Redding, J. C., 1997. Hardwiring the Learning

Organization. Training and Development 51, 61–67.

Rolland, C., Prakash, N., 2001. Matching ERP system

functionality to customer requirements, in: Fifth IEEE

International Symposium on Requirements

Engineering, 2001. Proceedings. pp. 66 –75.

Rolland, C., Prakash, N., Benjamen, A., 1999. A Multi-

Model View of Process Modelling. Requirements Eng

4, 169–187.

Senge, P. M., 1990. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and

Practice of the Learning Organization, Doubleday

Business., 1st ed.

Tosey, P., 2005. The hunting of the learning organization:

A paradoxical journey. Management learning 36, 335.

Tsang, E. W. K., 1997. Organizational learning and the

learning organization: a dichotomy between

descriptive and prescriptive research. Human relations

50, 73–89.

Waldrop, M. M., 1992. Complexity: The Emerging

Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos, Simon &

Schuster., 1st ed.

Watkins, K. E., Marsick, V. J., 1993. Sculpting the

Learning Organization: Lessons in the Art and

Science of Systemic Change, Jossey-Bass., 1st ed.

Yang, B., Watkins, K. E., Marsick, V. J., 2004. The

construct of the learning organization: Dimensions,

measurement, and validation. Human Resource

Development Quarterly 15, 31–55.

ModelingtheCreationofaLearningOrganizationbyusingtheLearningOrganizationAtlasFramework

285