Memorability Experiment Vs. Expert Method in Websites Usability

Evaluation

Marek Miłosz, Magdalena Borys and Maciej Laskowski

Institute of Computer Science, Lublin University of Technology, Lublin, Poland

Keywords: Memorability, Web Usability, Expert Analysis, Experimental Method, Website Usability Evaluation.

Abstract: The quantitation of website usability is possible by using experimental method with a group of users and

experts. In this paper an experiment of determining the short memorability is presented, along with using its

results for the comparative assessment of usability of Polish public administration websites. The expert

review was conducted on the same websites using the authors’ list of control questions and method for

determining the complex assessment of website usability. The degree of correlation of both methods is

presented and discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the early 1990s usability becomes a key issue in

software industry and lots of methods testing and

assuring usability have been developed since then.

The usability is often a purely economic matter

(Rajanen and Jokela, 2004). However, it has to be

noticed that usability issues do not only appertain to

the commercial software – they do apply to all of the

software services, also those public or non-

commercial (Lee and Koubek, 2012); (Topaloglu et

al., 2012).

Adjusting the software and its interface in order

to meet the needs of its users is not only essential

due to economic causes. It may also be an important

legal matter because the legislation in many

countries and EU, focused on providing universal

access to the information published online to all of

their citizens, have been introduced (Laskowski and

Szymczyk, 2010).

The main focus in the field of usability is laid on

the relative effectiveness of empirical usability

studies in opposition to other, less costly, methods.

The expert based methods held the promise of

usability results that kept cost low by relying on

expert review or analysis of interfaces rather than

observing actual user behavior (Hollingsed and

Novick, 2007). The experiment presented in the

paper shows the correlation between expert based

evaluation method and actual user performance.

2 USABILITY OF WEBSITES

The idea of usability, although intuitively easy to

explain, is indeed a very complex concept

(Landauer, 1996). It generally applies to user

interface, although is influenced by other factors,

such as ontology and information architecture of the

service (Lee et al., 2011); (Seffah et al., 2006).

The growth of the Internet and Web technologies

resulted in the development of Web usability as part

of usability as general. Huge variety of users,

meaning a variety of abilities, needs, used software

and hardware also imprints the Web usability

(Landauer, 1996); (Lee et al., 2011)

Classically, usability is defined by five different

components of websites (Nielsen, 1993):

Learnability, meaning the user’s ability to work

with the website while using it for the first time.

Use efficiency, meaning the productivity of user

while working with the website.

Memorability, also referred as retainability (e.g.

Montero et al. 2008), meaning the user’s ability

to reach the efficiency in working with website

after a long period of not using it. This property

is especially important for websites, which are

used only occasionally.

Errors, which are usually connected with the

approach how users handle errors and how the

web application supports this process. This

mainly applies to errors in human-computer

interactions.

151

Miłosz M., Borys M. and Laskowski M..

Memorability Experiment Vs. Expert Method in Websites Usability Evaluation.

DOI: 10.5220/0004453801510157

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 151-157

ISBN: 978-989-8565-61-7

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Satisfaction – this property strongly influences

on the rate of user return in case of websites used

occasionally.

The first properties listed by Nielsen are connected

to the web application learning curve (Figure 1),

meaning the change of user productivity as his

experience grows. In classical applications the initial

productivity (meaning the productivity measured

during the very first contact with the application –

marked in Figure 1 as L/M) is negative in many

cases. A user is learning how to work with the

application by involving other users in this process

and – as a consequence – decreasing their

productivity (Göransson et al., 2003).

In case of web applications this point can be

close to 0 (low usability) or to the point of maximum

productivity (perfect usability). Of course higher

productivity (marked in Figure 1 as P) means higher

usability of the discussed web application.

Figure 1: Learning curve.

Figure 2: The initial and renewed learning curve.

The position of L/M point and the curve slope in

Figure 1 during the first contact is a measure for the

ease of learning and – in case of the second contact

after a break – the memorability (Figure 2).

Figure 2 presents the comparison of the learning

curves during the first contact with web application,

the second (after a break) and another one. L, M

1

and M

2

points show the initial user productivity

during the first and subsequent contacts with the

web application. Due to memorability, we should

observe the relation between the values: L< M

1

< M

2

<... . It means that the initial productivity increases

from one to next using of a web application.

The same approach can be also seen in many

different definitions of usability presented in

literature (e.g. Montero et al., 2008). Despite the fact

that memorability (also referred as Ease to be

remembered or Learning-time) is listed as one of

important factors of usability, there is not many

research focus on it. The economic model of

memorability was discussed recently (Miłosz and

Lujan-Mora, 2013). The other research concentrate

rather on software elements such as mobile service

notifications (Garzonis et al., 2009), information

charts (Bateman et al., 2010), visualization graphs

(Ghani and Elmqvist, 2011) and so on. On the other

hand the usability testing of web applications was

proposed as a part of developing cycle in agile

methods (Lujan-Mora and Masri, 2012)

3 MEASURING USABILITY

Due to its complexity, the usability cannot be

measured directly (Cakir and Oztaysi, 2009).

Through operationalization of the usability

construct, the specified variables defining usability

(product attributes) were introduced in usability

analysis (see: (Palmer, 2002); (Hornbaek, 2006)).

There are many different methods for evaluating

usability as well as many metrics to measure of the

usability level.

3.1 Usability Evaluation Methods

Classification

In recent years, many Usability Evaluation Methods

(UEMs) have been employed to assess websites

(Palmer, 2002); (Cakir and Oztaysi, 2009);

(Pressman and Lowe, 2009).

Regarding to type of evaluation performed,

UEMs can be classified into one of following

categories (Fernandez et al., 2011): automated or

manual.

On the other hand, the following group of UEMs

can be defined taking into consideration the type of

UEMs used in analysis (Petrie and Bevan, 2009):

automated checking of guidelines and standards

conformance,

expert evaluation,

evaluation with users or potential users,

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

152

evaluation using models and simulations,

evaluation of collected data during (evaluated)

system usage.

Among presented UEMs groups, the evaluation

carried out by experts is the most frequently used. It

usually used as an independent analysis or in

combination with methods from other groups.

An expert-based evaluation is performed by

a usability expert, domain expert or double expert,

who has expertise both in usability and in particular

type of interface being evaluated, to identify defects

in the interface. There are following expert-based

usability evaluation methods:

Expert review.

Cognitive walkthrough.

Pluralistic walkthrough.

Heuristic evaluation.

Heuristic walkthrough.

Guidelines inspection.

The methods referred as reviews or inspections do

not use task scenarios, in opposite to task-based

evaluations are referred as walkthroughs.

3.2 Usability Metrics Overview

UEMs measure product attributes using different

metrics (Palmer, 2002). A metric relates a defined

evaluation approach and a measurement scale.

Thereby, the decision which metric of usability use

is the consequence of selected UEM.

Moreover, the selection of metrics demands the

understanding of the relation between different

measures of usability as well as limitations of

employed usability metrics.

There are few types of usability metrics that can

be used during a usability evaluation. The simple

classification of usability metrics is the following

(Tullis and Albert, 2008):

performance metrics,

issue-based metrics,

self-reported metrics,

behavioural and physiological metrics.

Many examples of the usability metrics usage can be

found in mentioned book (Tullis and Albert, 2008).

3.3 Used Approach

In the presented research, two new metrics for

quantitative assessment of the websites usability

have been used.

The first metric uses the results of memorability

experiment and can be called as a Memorability

Level metric. The Memorability Level (ML) is

calculated as:

f

f

T

TT

ML

(1)

where:

f

T - the average (arithmetic mean) execution time

of performing tasks for the first time by

inexperienced users;

T - the average execution time of performing

tasks for n-time by experienced users

(

n

).

The value of ML is calculated as an average time in

the group or users, working with website or web

application. According to (Woolrych and Cockton,

2001) the number of users in an experiment may be

small – from ten to fifteen participants are enough

for the properly experiment conducting. Higher

value of ML means the website is easier to

remember between visits, thus it can be conclude

that the quality of UI is higher (better).

The second metric applies to quantitative

assessment of the website interface usability is the

Web Usability Points (WUP).

4 WEB USABILITY POINTS

In order to obtain the best results in evaluating

usability of websites, the mix of an expert review

and a short cognitive walkthrough method was

proposed. The proposed method covers the

following areas:

Application interface.

Navigation and data structure.

Feedback, system messages, user help.

Content (e.g. of a website).

Data input.

Table 1 shows the detailed list of areas and subareas

(tentatively called “LUT list”) with questions

assigned to each point. Accordingly, Table 2

presents the grading scale used to assess each tested

area.

The results of proposed evaluation approach can

be used to calculate Web Usability Points as a

complex factor (rate) of the usability of websites

GUI. WUP metric uses grades (Table 2) granted by

experts to each question from the LUT list (Table 1).

MemorabilityExperimentVs.ExpertMethodinWebsitesUsabilityEvaluation

153

WUP for websites can be calculated as:

ij

ia

q

k

ijk

s

j

ij

n

i

ia

p

qsn

WUP

11

111

(2)

where:

a

n - number of areas,

i

s - number of subareas in i-area,

ij

q - number of questions in i-area and j-subarea,

ijk

p - grade value (points) granted to k-question in

j-subarea in i-area.

The value of WUP varies from 1 to 5. The higher

value indicates better usability of the interface.

Table 1: LUT list of predefined testing areas with

questions assigned.

Web application interface

Layout

Is the layout readable?

Is it adjusted to different resolutions?

Is it adjusted to mobile devices?

Is it consistent?

Does it support task implementation?

Color scheme

Is there proper contrast between text and

background ?

Is the color scheme readable for people with

color vision disorders?

Is the color scheme readable on various

kinds of displays?

Navigation and data structure

Ease of use

Is the access to all sections of a web

application easy and intuitive?

Is the access to all functions of a web

application easy and intuitive?

Information

hierarchy

Isn’t the information hierarchy too

complicated?

Information

structure

Is the information structure understandable

for users?

Is it consistent?

Is it well planned?

Screen

elements

Do they support the navigation?

Feedback, system messages, user help

System

messages

(general)

Do they provide enough information on the

status of actions performed by user?

System

messages

(errors)

Do they contain hints on problem solution?

Feedback and

user help

Does the information appear in places,

where it may be needed?

Is the provided information understandable

for an average user?

Is the provided information accessible for an

average user?

Is it possible for an average user to perform

actions suggested by system help in order to

solve the encountered problem?

Table 1: LUT list of predefined testing areas with

questions assigned. (cont.)

Content

Labels

Do the labels used in the interface provide

enough information?

Do all the interface elements have necessary

labels?

Naming

Is the interface naming understandable for

its users?

Is the interface naming consistent?

Page text Is it understandable for users?

Data input

Data

Is the data validated by the form elements?

Do the forms have elements acting as hints

for the input data (e.g. on format or data

range)?

Can average user fill in the form easily?

Forms

Are they designed in a readable way?

Are they adjusted to the mobile devices?

Do they allow user to input all of the

necessary data?

Table 2: Grading scale applied to LUT list.

Grade Description

1

Critical GUI errors were observed, preventing

normal usage or discouraging user from using the

web application.

2

Serious GUI issues were encountered, which may

prevent most users from task realization.

3

Minor usability GUI issues were observed, which if

accumulated may have negative impact on user

performance.

4

Single minor GUI issue was observed, which may

have negative impact on user work quality (e.g.

poor readability).

5

No GUI issues influencing either user performance

or work quality were identified.

5 EXPERIMENT AND RESULTS

5.1 Research Question

The goal of our study is to examine the

memorability experiment usefulness from the point

of view of the following research question:

”Whether the memorability experiment provides

comparable results in the usability evaluation to

other methods”. Since the research question is broad,

it has been decomposed into two sub-questions to be

addressed. These research sub-questions are the

following:

1. Does memorability experiment provide the

usability assessment in rating scale?

2. Are the Memorability Level and Web Usability

Points metrics comparable?

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

154

5.2 Research Hypotheses

To examine the research question following research

hypotheses were formulated:

1. Memorability experiment provides usability

assessment in rating scale.

2. Results of evaluations provided by memorability

experiment and expert review method are

comparable.

5.3 Research Methodology

The research hypotheses were verified by

experimental works. The experiments were

conducted on three websites of public administration

offices in following cities: Warsaw, Lublin and

Chełm. All websites contains the same features and

were created based on the same law and principles to

access to public information in Poland named Public

Information Bulletin (in Polish: BIP).

Research methodology consisted of the

following phases:

1. The assessment of WUP for each website using

proposed method with LUT list.

2. Experimental determination of ML value for

each website tracking the performance of group

of participants using special scenario for short

term memorability analysis.

3. The analysis of obtained data to verify the

research hypothesis.

The first phase involved the described method of

expert review and short cognitive walkthrough using

LUT list (Table 1), proposed grading scale (Table 2)

and formula (2).

The second phase was a regular experiment with

group of 15 participants (13 males and 2 females)

performing the same task for three websites. All

participants were Bachelor’s Degree students of

Computer Science at the Faculty of Electrical

Engineering and Computer Science of Lublin

University of Technology. The task was repeated

each 30 minutes. Figure 3 shows the experiment

schema.

Experiment 1 Experiment 2 Experiment 3

30 min 30 min 30 min

Figure 3: Time planning of the short memorability

experiment.

Between the sequences of carried out tasks, the

participants performed other activities with

computers. Those other activities were not

connected with the research. The tasks were simple

and short-term. The web browser had the browsing

history option disabled and the participants were

allowed to use only the tools provided by the

assessed websites. In addition, the participants

changed the workstations between each task

sequence. The results (duration of the task

performance) were recorded and averaged for the

entire group.

The third phase involved the analysis of data

obtained, performing the calculations, creating the

charts and examining the correlation between WUP

and ML in the group of websites. As a measure of

the degree of correlation, the Pearson correlation

coefficient was used.

5.4 Results

The results of expert review of tested websites are

shown in Table 3. WUP was calculated using the

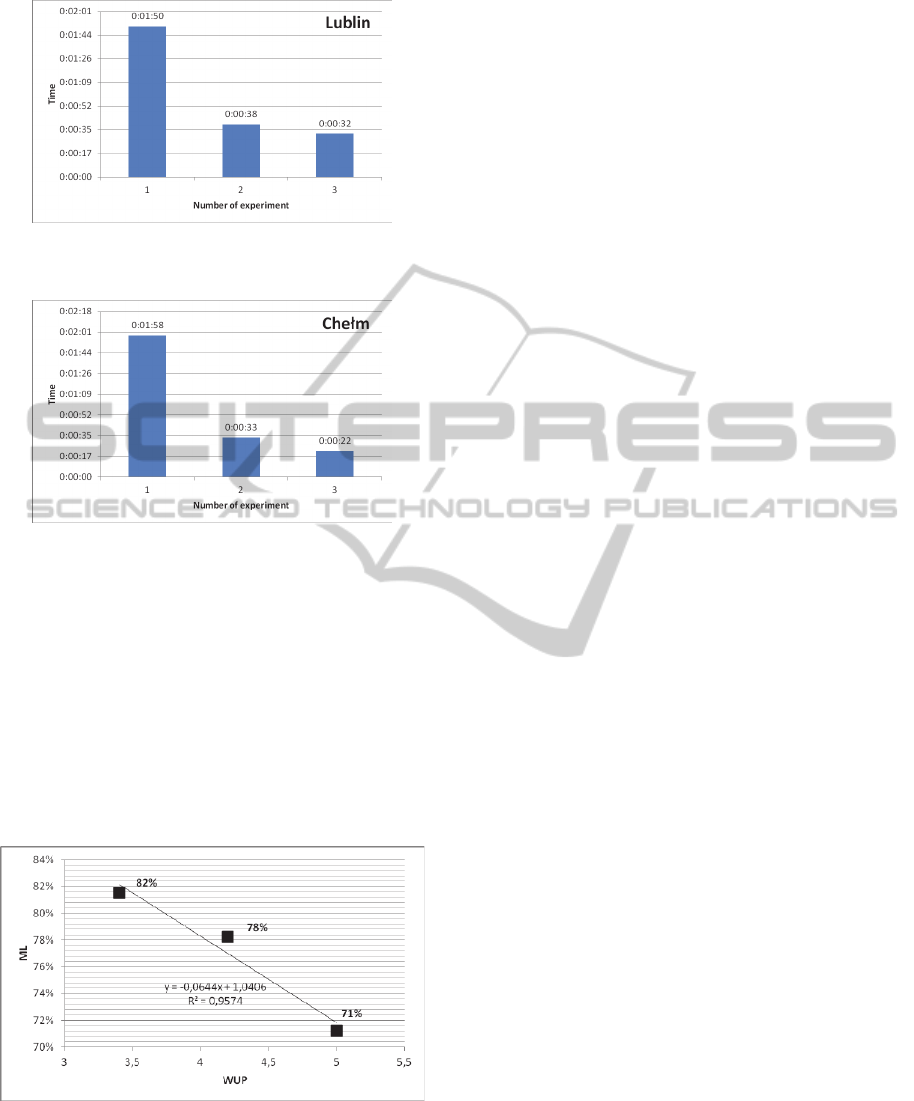

formula (2). Table 4 and Figures 4-6 present the

memorability experiment results.

Table 3: Results of expert review - websites WUPs.

No Name of the website WUPs

1

Public Information Bulletin of

Warsaw (BIP Warsaw, 2013)

4.2

2

Public Information Bulletin of

Lublin (BIP Lublin, 2013)

5.0

3

Public Information Bulletin of

Chełm (BIP Chełm, 2013)

3.4

Table 4: Results of memorability experiment –

memorability levels of websites.

No Name of the website ML

1

Public Information Bulletin of

Warsaw (BIP Warsaw, 2013)

78.3%

2

Public Information Bulletin of

Lublin (BIP Lublin, 2013)

71.2%

3

Public Information Bulletin of

Chełm (BIP Chełm, 2013)

81.5%

Figure 4: Results of memorability experiment for BIP

Warsaw.

MemorabilityExperimentVs.ExpertMethodinWebsitesUsabilityEvaluation

155

Figure 5: Results of memorability experiment for BIP

Lublin.

Figure 6: Results of memorability experiment for BIP

Chełm.

The analysis of correlation between the values of

two measures of websites usability shows that there

is a strong negative correlation (Figure 7). Pearson's

coefficient for the experiments is: -0.97. The result

is rather surprising: better GUI usability rate the

lower memorability level. This may be explained by

the fact that a good interface does not force user to

remember website structure and navigation,

therefore user performs task each time with the same

efficiency.

Figure 7: Correlation between WUP and ML.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The main purpose of this research was to investigate

if the memorability experiment provides comparable

results in the GUI usability evaluation to other

evaluation methods, such as the expert review.

The analysis of results for Hypothesis 1 showed

that memorability experiment can provide data to

assessment of websites usability in a rating scale.

The Memorability Level metric is proposed in this

paper.

The main result of the study is to identify the

existence of possible correlation between the

assessment of website interface usability provided

by the expert and Memorability Level which is

determined during the experiment with the real

website users. Website interface usability can be

measured in Websites Usability Points, proposed in

this paper.

Moreover, in the paper the relationship between

ML and WUP was studied, based on examination of

three websites with similar features and purpose.

Hypothesis 2 (Comparability of expert and

memorability methods) has been fully confirmed.

During the research the statistical correlation

between the two indicators: WUP and ML of

website has been found. Correlation is negative

(which is unexpected) – the higher usability of

website GUI measured in WUP causes the lower

memorability level.

Discovered relationship can be used to examine

GUI usability through memorability testing.

However, the statistical indicators (Pearson

coefficient) were determined for relatively small

population of websites. Therefore, the results should

be verified in more extensive study, which will

include a larger number of websites and their greater

diversity. It is also possible to introduce an

additional dimension to the experiment to reflect

user experience. Therefore the research can be

extended to include different groups of Internet

users.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors would like to thank all students who took

part in the experiment for their contribution to this

paper.

REFERENCES

Bateman S., Mandryk R. L., Gutwin C., Genest A.,

McDine D., Brooks Ch., 2010. Useful Junk? The

Effects of Visual Embellishment on Comprehension

and Memorability of Charts. In CHI '10 Proceedings

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

156

of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, NY, pp. 2573-2582.

BIP Chełm, Public Information Bulletin of Chełm, http://

chelm.bip-gov.info.pl/bip/

BIP Lublin, Public Information Bulletin of Lublin, http://

bip.lublin.eu

BIP Warsaw, Public Information Bulletin of Warsaw,

http:// bip.warszawa.pl.

Cakir C. B.; Oztaysi B., 2009. A model proposal for

usability scoring of websites. In International

Conference on Computers & Industrial Engineering,

CIE 2009, 6-9 July 2009, pp.1418-1422.

Fernandez A., Insfrán E., Abrahão S., 2011. Usability

evaluation methods for the web: A systematic

mapping study. In Information & Software Technology

53(8), pp. 789-817.

Garzonis S., Jones S., Jay T. and O’neill E., 2009.

Auditory icon and earcon mobile service notifications:

intuitiveness, learnability, memorability and

preference. In CHI '09 Proceedings of the SIGCHI

Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems,

NY, pp. 1513-1522.

Ghani S., Elmqvist N., 2011. Improving revisitation in

graphs through static spatial features. In GI '11

Proceedings of Graphics Interface 2011. Waterloo,

Canada, pp. 175-182.

Göransson, B., Gulliksen, J., Boivie, I., 2003. The

usability design process – integrating user-centered

systems design in the software development process.

In Software Process: Improvement and Practice, Vol.

8, Issue 2, pp. 111–131.

Hollingsed T., Novick D. G., 2007. Usability Inspection

Methods after 15 Years of Research and Practice. In

SIGDOC '07 Proceedings of the 25th annual ACM

international conference on Design of communication,

NY, pp. 249-255.

Hornbaek K., 2006. Current Practice in Measuring

Usability: Challenges to Usability Studies and

Research, In International Journal of Human-

Computer Studies, Volume 64, Issue 2 , February

2006, pp. 79-102.

Landauer Th. K., 1996. The Trouble with Computers:

Usefulness, Usability, and Productivity. MIT Press.

Laskowski M., Szymczyk T., 2010. Economic and legal

aspects of adjusting online advertisements for visually

impaired, In: Actual Problems of Economics, No. 6

(108), pp. 301-308

Lee K. I., Jin B. S., Ji Y. G., 2011. The scenario-based

usability checklist development for home appliance

design: A case study. In Human Factors and

Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries,

January/February 2011, Vol. 21, Issue 1, pp. 67–81.

Lee S., Koubek R. J., 2012. The effects of usability and

web design attributes on user preference for e-

commerce web sites. In Computers in Industry,

Vol. 61, Issue 4, May 2010, pp. 329–341.

Lujan-Mora, S., Masri, F., 2012. Integration of Web

Accessibility into Agile Methods. In Proceedings of

ICEIS 2012 Conference, pp. 123-127.

Miłosz M., Lujan-Mora S., 2013. Economical Aspect of

Website Memorability. In Actual Problems of

Economics, Issue 4 (142) (in press)

Montero F., Lozano M. D., Gonzales P., 2008. Usability-

Oriented Quality Model Based on Ergonomic Criteria.

In: Muñoz C. C., Moraga A., Piattini M. (2008)

Handbook of Research on Web Information Systems

Quality, IGI Global, NY, pp. 220-233.

Nielsen J., 1993. Usability Engineering. Morgan

Kaufmann, San Francisco.

Palmer J. W., 2002. Web site usability, design, and

performance metrics. In Information Systems

Research, 13(2), pp. 151-167.

Petrie H., Bevan N., 2009. The evaluation of accessibility,

usability and user experience. In The Universal Access

Handbook. CRC Press.

Pressman R. S., Lowe D., 2009. Web Engineering:

a Practitioner's Approach. McGraw-Hill, NY.

Rajanen M., Jokela T., 2004. Analysis of Usability Cost-

Benefit Models. In Proceedings of the Twelfth

European Conference on Information Systems (Leino

T, Saarinen T, Klein S. eds.), Turku School of

Economics and Business Administration, Turku,

pp. 1535-1545.

Seffah A., Donyaee M., Kline R. B., Padda H. K., 2006.

Usability measurement and metrics: A consolidated

model. In Software Quality Control, Vol. 14, Issue 2,

pp. 159–178.

Topaloglu, H., Gumussoy, C. A., Bayraktaroglu, A. E. and

Calisir, F., 2012. The relative importance of usability

and functionality factors for e-health web sites. In

Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing &

Service Industries.

Tullis T., Albert W., 2008. Measuring the User

Experience: Collecting, Analyzing, and Presenting

Usability Metrics. Morgan Kaufmann, 1

st

edition.

Woolrych, A., Cockton, G., 2001. Why and When Five

Test Users aren't Enough. In Proceedings IHM-HCI

Conference, Volume 2, pp. 105-108.

MemorabilityExperimentVs.ExpertMethodinWebsitesUsabilityEvaluation

157