Look Me in the Eye if You’re a Man

The Impact of Gender Cues on Impression Formation in Online Professional

Profiles

P. Saskia Bayerl

1

and Monique Janneck

2

1

Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands

2

Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Luebeck University of Applied Sciences, Luebeck, Germany

Keywords: Impression Formation, Visualization, Gender, Recruiting, Hyperpersonal Cues.

Abstract: Online profiles are becoming increasingly important in work contexts from recruiting to termination

decisions. We conducted an experiment to investigate the effect of profile layout and more specifically

gender cues on professional impression formation (n=202). The presence or absence of a photo had no

impact on overall ratings or profile likability. Layout, however, interacted with gender of the profile owner

in that male profiles were rated most positively with photo, female profiles without photo. Silhouette images

providing only generic gender cues led to similarly low ratings for male and female profiles. Our study has

implications for users managing their attractiveness on the job market as well as for HR professionals and

organizations. It further extends our understanding of the gendered nature of professional online settings.

1 INTRODUCTION

In 2011, 56% of companies used the internet for

recruitment; an additional 20% were planning to do

so in the future (SHRM, 2011). This is a

considerable increase compared to 2008 (34%;

SHRM, 2008) and illustrates the growing

importance of online information for HR decisions.

The internet, and here especially social media

services, have become an important source of

information from recruitment to termination

(Davidson, Maraist, and Bing, 2011).

New online environments provide users with a

wide range of possibilities from text-only elements

to the posting of photos, videos or even interactive

content (e.g. gifts, hugs, virtual kisses, or gaming

and event invitations). This raises the question what

type of information users should post on their

profiles and in what way to guarantee the best

possible impressions in potential viewers.

In this paper we investigated the impact of visual

gender cues in online profiles on impression

formation in a professional context. Gender remains

one of the most pervasive influences in work-related

contexts. Studies in written (i.e., offline) CVs

repeatedly demonstrate that gender information

impacts the chances of being hired as well as the

proposed salary, and perceptions of competence

(e.g., Moss-Racusin, Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham and

Handelsman, 2012), and that visual cues play here a

particularly biasing role (Cann, Siegfried and

Pearce, 1981; Watkins and Johnston, 2000).

Research on gender-cues for impression formation

in online settings has so far focused predominantly

on personal relationships such as the development of

friendships or romantic relationships, while

professional contexts have been largely ignored.

Yet, the processes for choosing a friend or dating

partner are likely to differ considerably from

choosing a potential employee. Our study aims to

increase our understanding of the gendered nature of

professional online settings.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 Online Profiles for Impression

Management and Formation

Personal information online is often provided in

profiles, a format similar to a traditional CV, usually

containing a picture, current employment, education,

professional history, and at times hobbies and

personal endorsements by colleagues or friends.

541

Saskia Bayerl P. and Janneck M..

Look Me in the Eye if You’re a Man - The Impact of Gender Cues on Impression Formation in Online Professional Profiles.

DOI: 10.5220/0004480705410550

In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (STDIS-2013), pages 541-550

ISBN: 978-989-8565-54-9

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

Services such as LinkedIn, with its mission to help

its members to “stay informed about your contacts

and industry, find the people knowledge you need to

achieve your goals” are specifically geared towards

professionals. Other sites such as Facebook,

MySpace or Twitter have a more personal mission,

but are still routinely used by HR professionals

(SHRM, 2011). Online profiles can thus have a

considerable impact on our professional lives.

Users are well aware that they need to manage

their self-representations to create the best

impression possible and that online profiles are a

potent way to influence impression formation. As

such self-presentation is a strategic activity “to

convey an impression to others, which it is in [a

person’s] interests to convey” (Goffman, 1959, p. 4).

In this sense, impression management can be

understood as “the goal-directed activity of

influencing the impressions that audiences form of

some person, group, object, or event” (Schlenker

and Britt, 1999, p. 560).

Due to the asynchronous and often (semi-)

anonymous nature of online communication, users

experience greater control over their self-

presentation. For instance, they may choose

especially favorable images and descriptions,

include or consciously omit personal information

such as age or relationship status or post comments

and links indicating an interesting, ‘well-rounded’

personality (e.g., Zhao, Grasmuck, and Martin,

2008). By placing personal information in their

profiles, users make explicit identity claims, which

are used by viewers to construct a picture of their

personality (Vazire and Gosling, 2004). Some even

use the relative anonymity of the internet to create a

whole new personality on the Web leading to

questions of deception and identity construction in

online communication and relationships (e.g. Stone,

1996; Turkle, 1995; Donath, 1999; Gibbs, Ellison

and Heino, 2006).Yet, while users conduct

impression management, it is questionable whether

they are always aware of the impact of their design

choices (Labrecque, Markos and Milne, 2011).

A first impression of a person often decides

whether further contact is looked for and thus

whether a relationship develops at all. Impression

formation is thus an important step in the

development of relationships (Goffman, 1959).

People meeting exclusively online lack the clues

available in face-to-face situations such as age, sex,

ethnicity or physical appearance to form immediate

impressions. In such ‘zero-history relationships’

online profiles often provide the information

normally collected during a first personal meeting,

and allow viewers to form a – more or less detailed

or truthful – impression about the person. Much as

website quality is seen by potential buyers as a

signal of product quality (Wells, Valacich and Hess,

2011), the layout of online profiles sends signals

about a person’s attractiveness as potential friend,

partner or employee. In this process, visual cues

about a person obtain a particularly important role.

2.2 The Role of Visual Cues

in Impression Formation

Theories such as social presence (Short, Williams

and Christie, 1976) and media richness (Daft and

Lengel, 1984, 1986) assume that relationship

formation is hindered in online environments due to

the lack of physical presence, which creates

restricted, ‘one-dimensional’ pictures of a person. If

a person is unknown, the lack of information leads

to uncertainty and thus to a more negative picture of

a person when compared to face-to-face encounters

(Berger and Calabrese, 1975). In such situations,

visual information can reduce uncertainty about an

interaction partner. Visual cues such as age, gender,

attractiveness or ethnicity are one of the most

important aspects for impression formation and

management, and as such critical for the initial

evaluation of an interaction partner and the decision

to pursue further acquaintance (Duck, 1982), be it

online of offline. Using photos in online

environments should thus lead to more positive

impressions of interaction partners (e.g., Berger and

Douglas, 1981).

The hyperpersonal communication model

proposed by Walther (1996, 1997) makes exactly the

opposite prediction. The hyperpersonal model

suggests that anonymity – or more generally the lack

of knowledge about a communication partner – may

lead to exaggerated positive perceptions instead of

negative ones. In online environments, senders can

carefully select, which information they show about

themselves or what they communicate and how.

This selectiveness provides the counterpart with a

(probably) highly positive picture of the person that

is independent from (perhaps more negative) aspects

the sender cannot control such as physical

attractiveness. This leads to a more positive attitude

in the viewer than might be the case in an offline

encounter. These positive expectations, in

consequence, will lead to more positive feedback

and thus create a ‘self-fulfilling’ prophecy of

positive impressions. In this way, the absence of

information can actually lead to a more positive

(hyperpersonal) impression of a person. Support for

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

542

this process was found by Hancock and Dunham

(2001), who showed that, while the breadth of

impressions in zero-history online encounters is

lower compared to face-to-face situations, the

intensity of impressions is higher. That is,

interaction partners rate their counterpart in a more

extreme way, if they only communicate with them

over text.

While little debate exists that visual information

is an important factor for impression formation,

theoretical models make thus contradictory

predictions about their effect: Media richness and

uncertainty reduction theory predict a positive effect,

while the hyperpersonal communication model

suggests a more negative impact. Walther, Slovacek,

and Tidwell (2001) suggested a possible way to

solve this contradiction. Comparing short-term and

long-term virtual groups, they demonstrated that the

effect of visual information is moderated by the

length of relationships. For partners, who did not

know each other, the presence of a picture increased

affection and social attraction, while the introduction

of a picture at a later stage decreased mutual

attraction. Relationships conducted under CMC

conditions can over time become as personal and

intense as face-to-face relationships (e.g., Tidwell

and Walther, 2002; Wang, Moon, Kwon, Evans and

Stefanone, 2010; Walther et al., 2001). The negative

effects of computer-mediated communication are

thus confined to interactions, in which

communication partners have no former knowledge

of each other (so-called ‘zero-history’ encounters).

In a work context, and more specifically in

recruitment and selection decisions, zero-history

encounters tend to be the norm. Not knowing a

potential employee or colleague is a considerable

source of uncertainty. In this case online profiles are

usually viewed with the expectation of future

professional interactions. We therefore expect that in

this situation, additional personal information in the

form of a photo will improve first impressions of a

person. Professional profiles with photo should thus

lead to more positive ratings than profiles without

photo.

Hypothesis 1: Professional profiles with photo

will be rated more positively than professional

profiles without photo.

2.3 The Impact of Gender

People in online environments often rely on

stereotypes to make decisions about a person,

especially if little individuating information about a

person is available (Chan and Mendelson, 2010).

Stereotypes reduce overload, but also augment an

“information-impoverished environment” (Stangnor

and Schaller, 1996, p. 21). Prototypes are formed

based on own experiences or socio-cultural

categories and can be activated by subtle cues such

as user names.

One of the most pervasive bases for prototypes

and stereotyping is gender. Contrary to early hopes

of the equalizing effect of computer-mediated

communication, gender remains an important factor

also in online impression formation. Wiliams and

Mendelson (2008), for instance, found that

judgments on masculinity, femininity, and likability

were identical for men and women, if the gender of

the interaction partner was unknown. Knowledge of

the other’s gender, in contrast, led to gender-typical

attributions of men as more masculine and women

as more feminine. Viewers also base attributions of

another’s personality on gender cues in profiles

(Vazire and Gosling, 2004). Stereotyping effects,

and according reactions, can even be observed, when

the gender of a person is only inferred through a

gender-identifying name (Christofides, Islam and

Desmarais, 2009) or a computer-based avatar (Lee,

2004).

The effect of gender cues for online impression

formation is of great importance for professional

contexts, in which gender-stereotyping is still

pervasive despite decades of initiatives and tight

regulations through equality laws (e.g., Marlow,

Schneider and Nelson, 1997; Moss-Racusin et al.,

2012; Vancouver and Ilgen, 1989). While gender

information is hard to exclude from online profiles,

especially in a professional context, the question

remains how prevalent this information should be.

The strongest cue to gender is a personal photo,

whereas the presence of simply a name can be

considered a weak clue.

Given the importance of gender cues on online

impression formation and their biasing effect on

perceptions of men and women (cp. William and

Mendelson, 2008), we expect that the presence or

absence of strong gender cues will influence the

ratings of male versus female profiles also in

professional profiles. We do not make specific

assumptions of the direction of the effect.

Hypothesis 2: Presence or absence of a photo

will impact the ratings of male profiles differently

than female profiles.

Next to gender information photos also provide

information about the look of the person – thus

confounding the effect of gender cue strength with

the degree of an individual’s attractiveness. Physical

LookMeintheEyeifYou'reaMan-TheImpactofGenderCuesonImpressionFormationinOnlineProfessionalProfiles

543

attractiveness of applicants has been shown as a

continuous source for biases in work-related

contexts, although the relationship remains complex.

A meta-analysis by Hosoda, Stone-Romero and

Coats (2003) suggests that higher attractiveness

generally leads to more positive job-related

outcomes. Indications are that this relationship holds

also in non-Western cultures (Dion, Pak and Dion,

1990). Yet physical attractiveness can also have a

negative impact. This reversal of a “beautiful is

good” bias into the “beauty is beastly” effect

(Heilman and Surawati, 1979) seems to be driven by

task type. Higher physical attractiveness is counter-

productive for individuals applying to or working in

a position which is perceived as traditionally held by

the opposite sex (Cash, Gillen and Burns, 1977;

Heilman and Stopeck, 1985a, 1985b).

Online profiles (as well as traditional offline

CVs) generally offer the possibility to do without a

personal picture. In this case, however, online

profiles often contain generic gender information by

using a male or female silhouette (i.e., human

outline). Replacing the photo with a silhouette

eliminates individual features, while still indicating

the gender of a person. In such situations gender

information is emphasized, although de-

individualized. Given the fact that gender

information is a very powerful trigger for

stereotypes, the question arises whether such generic

gender cues play an (additional) role. If

attractiveness of the profile owner is the main factor

driving profile ratings, it may be expected that

without the personal picture, the effects of profile

gender would be less pronounced. We therefore also

investigated the following research question:

How does generic (i.e., depersonalized) gender

information impact impression formation in online

profiles?

3 METHODS

3.1 Design

To investigate the effects proposed in hypotheses 1

and 2, we compared professional profiles with and

without photos. We further added a third condition

introducing gender-indicating silhouette images to

investigate our research question on generic gender

cues. The study thus followed a 2x3 design testing

profile gender (female or male) and three variations

of profile layout: one with photo (strong gender cue

condition), one without photo (weak gender cue

condition), and one with a gender-indicating

silhouette images (generic gender cue condition).

Photographs were taken from a research database

(PICS, The Psychological Image Collection at

Sterling). To reduce biasing effects due to the

attractiveness of a person (cp. Hosoda et al., 2003),

photos were chosen with people of average

attractiveness. This was confirmed through ratings

by nine individuals (scale 1-7; range 3.80-4.89). No

significant difference was found in attractiveness of

male and female photos (t(8)= -.92, p=.39).

3.2 Sample

Undergraduate and graduate adult learners were

recruited through two online study panels at German

universities in return for study credit and the chance

to win a 25 Euro voucher from the online store

Amazon. A total of 257 people participated. We

excluded 51 participants, because they either did not

provide any profile ratings (drop-outs after the

introduction page or first profile, 46 participants) or

answered with the same rating for all profiles (5

participants). This retained 202 participants. The

majority of the students were female (77.2%). The

average age was 30.7 years (sd = 9.2) indicating a

mature sample.

3.3 Material and Procedure

We prepared two profiles for each combination of

within-subject factors, i.e., for each layout variation

two profiles were prepared for women and men,

leading to a total of 12 profiles. All profiles were

fictitious. Every profile provided the name of the

person to enable identification of the person as either

female or male, even if no photo was provided. It

further provided information on the location of the

person, his or her task, education, age, and areas of

special expertise. To make the profiles more

believable, we also included information on private

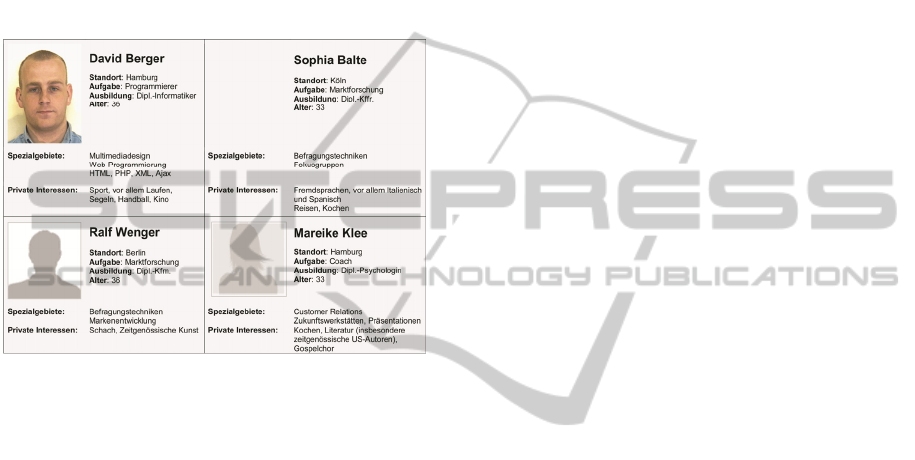

interests. Figure 1 shows examples of profiles with

and without picture as well as with male and female

silhouettes.

Participants rated all twelve profiles. Each

profile was presented on a separate page with the

profile shown on top of the page and the survey

questions directly below. The twelve profiles were

randomized to avoid sequence effects. At the end of

the survey, a separate page asked for demographic

information (gender, age, field of education, and

experience with virtual team work). Participants

were given the following instruction before the

rating:

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

544

You work in a company with branches in several

German cities. For a new project a team needs to be

created with members from several branches. The

project work will primarily be done ‘virtually’, i.e.,

using electronic media such as e-mail, video-

conferencing, etc. As part of the project team you

can participate in the selection of the team members.

Your task: On the next pages you will see personal

profiles of twelve potential team members. Please

consider them carefully and rate them according to

a short survey. [German in original]

Figure 1: Examples for the three layout variations.

Measures. Each person in the profile was rated on

12 aspects using a 7-step semantic differential (i.e.,

agreeable/disagreeable, friendly/unfriendly,

likable/dislikable, attractive/unattractive, sociable/

unsociable, civil/uncivil, successful/unsuccessful,

competent/incompetent, efficient/inefficient, reliable

/unreliable, active/inactive, correct/incorrect). All 12

aspects loaded on the same factor. We therefore

summarized the 12 aspects into one mean value for

an overall profile rating. The reliability of the

resulting scale was high with α = .98. A separate

item measured the overall likability of the profile

(“The profile appeals to me”) on a scale from ‘1:not

at all’ to ‘7:very much’. For the comparison of the

layout and gender variations, we summarized each

group of profiles (i.e., female with photo, male with

photo, etc.) into a rating variable for both the overall

profile rating and the likability evaluation.

Past research has shown that experience with

virtual environments can influence the perception of

online profiles (Nowak and Rauh, 2008). We

therefore included experience with virtual team

work as control variable (rated on a scale from ‘1:no

experience’ to ‘7:a lot of experience’). In addition,

we collected information on rater gender and age (in

years).

3.4 Results

Our hypotheses assumed a main effect for layout

(H1) and an interaction effect for layout and profile

gender (H2). We therefore conducted repeated-

measures ANOVAs for the two within-factors layout

and profile gender first for the overall profile rating,

then for the likability of the profile. We report

results using the conservative Greenhouse-Geisser

correction to account for violations of sphericity.

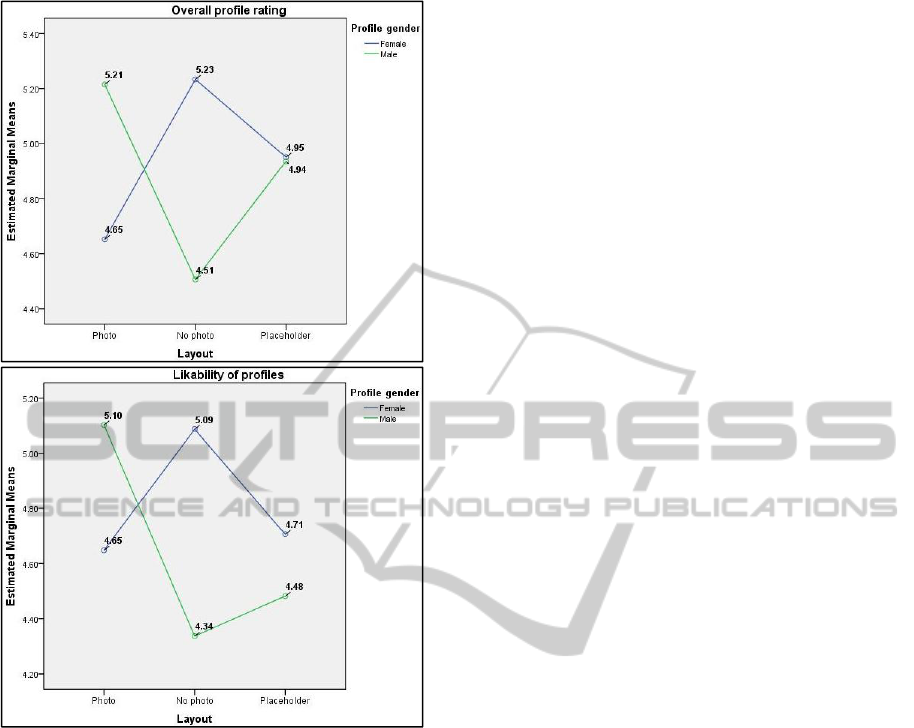

The three layout variations resulted in disparate

perceptions for the overall profile rating, F(2,198) =

8.23, p<.001, η

2

= .04, as well as likability, F(2,198)

= 8.69, p<.001, η

2

= .04. This effect was driven by

higher general ratings and higher likability of

profiles with photos compared to silhouette profiles

(pairwise comparison, p<.001). In contrast profiles

with and without photos were rated equally on both

outcomes measures. Hypothesis 1 was therefore not

supported.

In support of hypothesis 2, we found a

significant interaction between layout and profile

gender, F(2,198)

overall rating

= 36.40, p<.001, η

2

= .16;

F(2,198)

likability

= 42.87, p<.001, η

2

= .18. For both

the general perception and likability, male profiles

were rated more positively and more likable with

photo, while female profiles were rated more

positively and more likable without photo. Profiles

with silhouette images were rated nearly identical

for male and female profiles. The mean rating for

women approached the rating for profiles with

photos, the mean rating for men approached the

rating for the non-photo layout (see Figure 2).

In line with past research (e.g., Oliphant and

Alexander, 1982), we also found an influence of

rater gender on overall attractiveness of the profiles.

In our study women rated profiles more positively

than men, F(1,193) = 7.78, p<.01, η

2

= .04 (M

women

=

5.09, M

men

= 4.77). Rater gender was not significant,

however, for likability ratings, F(1,189) = 2.34, ns.

Age or experience had no significant impact on

profile perceptions for either dependent variable.

LookMeintheEyeifYou'reaMan-TheImpactofGenderCuesonImpressionFormationinOnlineProfessionalProfiles

545

Figure 2: Interaction effect of layout and profile.

4 DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to obtain a better

understanding of online impression formation in

professional settings. Our focus was here on online

profiles, which often provide the first point of

contact in virtual organizations or teams. Guided by

uncertainty reduction theory (Berger and Calabrese,

1975) and the hyperpersonal communication model

(Walther, 1996, 1997) we investigated how the

strength of gender cues influences the perception of

potential team members using an experimental

setting. We found that visual gender cues in online

profiles played a critical role in forming impressions

of people that are unknown, but might become

potential long-term cooperation partners.

In our study we attempted to differentiate

between effects of individual features of a person

and the generalized effect of gender in visual cues.

Overall, our findings suggest that gender in itself has

a stereotyping effect: For female profiles the gender-

marked silhouettes were rated in a similar way as

female profiles with photos. For male profiles, the

silhouette condition led to ratings similar to the non-

photo condition.

This study addresses the theoretical question of

how profile layout, and more specifically visual cues

in zero-history relationships with a possible long-

term focus impact online impression formation. It

thus extends considerations of impression formation

in zero-history encounters into a work-related

setting. It further adds the issues of gender

stereotyping to impression formation with

professional online profiles. The presence or absence

of a photo had no significant influence on profile

ratings. At first glance, the similarity in ratings of

profiles with and without photos seems surprising

and contradicts uncertainty reduction theory as well

as the hyperpersonal model. The similarity could be

explained, however, by the strong interaction effect

between layout and profile gender: men were

consistently rated more positively with photo, while

women were rated more positively without photo.

The opposing trends for female and male profile

thus masked the effect of layout. The use of gender-

marked silhouettes led to similar ratings for men and

women, albeit on the low side.

The photo, silhouette and no-photo conditions

can be seen as a sequence of elimination of

identifying cues. While for men elimination of

identifying visual cues was negative, for women the

complete elimination of personal as well as generic

gender cues resulted in the most positive ratings.

Results for male profiles thus mirror findings

expected under uncertainty reduction theory (Berger

and Calabrese, 1975), i.e., the more identifying

information is available about a man, the more

positively he is perceived.

Male profiles with a silhouette were rated as

negatively as profiles without photo, i.e.,

emphasizing gender had no additional (positive or

negative) impact on the overall evaluation of male

profiles. This suggests that the male gender may still

be considered a ‘default’ value that has little impact

on judgments, instead of a defining characteristic of

a person. For women, a visual reminder of gender

resulted in similarly negative perceptions of the

profile as the fully identifying photo. Our results for

female profiles thus follow predictions of the

hyperpersonal model for computer-mediated

communication (Walther, 1996, 1997).

A possible explanation for the clear negative

effect of visual cues (generic and identifying) on

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

546

female profiles may be the activation of

attractiveness stereotypes. In their study on the

willingness to initiate friendship, Wang et al. (2010)

found that attractive and unattractive photos yielded

converse effects in male and female raters: women

were less willing to befriend attractive women and

unattractive men, while men were less willing to

befriend unattractive women and attractive men. In

the no photo condition, male raters were

significantly more positive towards the female

profile than the male profile, whereas women did not

differentiate between the sexes. Our data did not

yield a similar interaction effect between layout,

profile gender and rater gender. A possible

explanation is that attractiveness is still a higher

priority for women than for men – not only for

personal or romantic relationships, but also in

professional contexts. Attractiveness of photos, for

instance, influences the likelihood of being chosen

in hiring decisions (Marlow et al., 1996). This bias is

especially strong – and negative – for unattractive

women. The external rating of the pictures indicated

an average attractiveness of the people depicted.

Perceptions of average attractiveness may thus have

played a role in the lower ratings for women in the

photo condition. Still, attractiveness cannot explain

that female profiles scored as badly in the generic

gender condition with silhouette images as in the

photo condition. The silhouette images provided

anonymity for the individual, but still conveyed

gender information. This suggests that even generic

indicators of gender may trigger gender-stereotypes.

This is in line with findings on gender-marked

avatars and gender-based representations of

computer programs (Lee, 2003, 2004).

4.1 Practical Implications

The gap between the private and the professional in

online environments is continuously shrinking – as

indicated by the increasing use of social media

networks by HR professionals (Davidson et al.,

2011; SHRM, 2011). Our study provides valuable

pointers for individuals how to adapt their profile for

most positive effect, but also tells a cautionary tale

for HR professionals. Professionally-tinted networks

such as LinkedIn allow the creation of personalized

profiles. Although a fixed template is provided, a

person can still decide which information to put

online (e.g., photo or no photo, level of detail on

education and work history, description of personal

interests). Our study suggests that individual choices

on layout and in particular the type of visual cues

may considerably influence the likelihood to be

approached as expert or potential employee (Caers

and Castelyns, 2011).

Our finding that gender-marked silhouette

images led to similar results as photos for women

suggesting that at least part of the results can be

attributed to gender, not attractiveness. This

underlines the importance of stereotyping also in

professional online contexts.

In practical terms our study suggests that the

rules of personal branding (Labrecque et al., 2011)

for men and women may differ considerably,

starting with the inclusion of personal photos,

silhouette images, or the choice to stay anonymous.

When choosing a photo, it seems that women have

to take greater care with the choice of their photo

than men (i.e., choose more attractive pictures) to

reach the same result.

Our study also has implications for organizations

and online service providers. From studies on

traditional CVs we know that layout can be an

important predictor of how capable a candidate is

perceived and thus his or her chance of being

shortlisted for hiring decisions (Arnulf, Tegner and

Larsson, 2010). Our results suggest that layouts in

online profiles may have similar impacts. Online

services often force users to adhere to pre-specified

layouts. Such standard templates, which prescribe

specific layouts such as the presence or absence of

personal photos may, however, systematically

disadvantage certain groups. Service providers

should therefore consider allowing higher flexibility

in profile templates. In the same regard hiring

organizations should be sensitive how their

requirements for the presentation of information

may impact the chances of (potential) employees

(Brown and Vaughn, 2011).

4.2 Limitations and Future Work

While we think that our study provides valuable new

pointers for theory and practice, we are also aware

of several limitations. Firstly, in our study we

considered overall judgments and likability of the

profiles, not selection decisions. In as far as liking

and actual selection may be based on disparate

criteria it is possible that these two processes may

lead to different results. Further studies should thus

include actual choices. Moreover, our sample

consisted of students not HR professionals or actual

team members. Although we chose adult students

with prior working experience, their judgments may

differ from people with a clear HR role. Future

studies should thus consider professionals as well as

investigate in what way job role affects online

LookMeintheEyeifYou'reaMan-TheImpactofGenderCuesonImpressionFormationinOnlineProfessionalProfiles

547

impression formation.

A related question concerns the impact of task

type on the effect of online profiles, especially

considering the consistent gender effect in our study.

The gender-type of task (i.e., tasks that are seen as

either typically ‘feminine’ or ‘masculine’) impacts

how competent attractive or unattractive people are

perceived for this job, in that attractiveness is in fact

negative for gender-untypical jobs (Heilman and

Saruwatari, 1979). The instruction in our study was

kept very generic and can thus be considered as

gender neutral. Further investigations of layout

conditions for disparate task types could yield

important insights into interaction between job

content and gender-based online impression

formation.

Our profiles also included information on

hobbies and personal interests. We cannot exclude

that this information impacted attractiveness ratings

in an uncontrolled way, for instance, in case of

gender-typical or untypical hobbies. However,

personal information is not uncommon in online

profiles (e.g., in the form of group memberships,

private statements, or endorsements) or in related

services (e.g., on the Facebook of a LinkedIn user).

How private information in relation to visual gender

cues in online profiles shapes online impression

formation remains an interesting question, also in

light of user profiles in multiple online services.

Another interesting aspect may be the role of

gender for organizational impression formation.

Diversity cues such as race on recruitment websites

influence job seeker’s perceptions of an

organization’s attractiveness (Walker, Feild,

Bernerth and Becton, 2012). Based on our findings,

we suspect that visual presentations of gender might

have a similarly strong effect on initial impression

formations also for organizations. Considering the

growing trend of presenting organizations and

products as ‘personas’, taking a broader view of

gendered online impression formation may help

predict positive or negative reactions in target

groups.

In step with the growing importance of

cyberspace for personal and work life, online

profiles are becoming increasingly elaborate spaces

for self-presentation – including, for instance, logos,

interest groups, links to music bands and videos,

newest statistics of favorite online games, polls,

information on friends and colleagues as well as

professional recommendation. This opens new,

flexible, and elaborate possibilities for online

presentation, which together are likely to have

complex effects on online impression formation. In

particular, in work-related contexts the possibility to

include external endorsements and recommendations

may have a profound impact, similar to ratings in

online shops such as Amazon. While our study

provides pointers on the effects of layout differences

and gender, future studies are needed that include a

more comprehensive view on online profiles.

REFERENCES

Arnulf, J. K., Tegner, L., Larssen, O. 2010. Impression

making by résumé layout: Its impact on the probability

of being shortlisted. European Journal of Work and

Organizational Psychology, 19 (2), 221-230.

Berger, C. R., Calabrese, R. J. 1975. Some explorations in

initial interaction and beyond: Toward a

developmental theory of interpersonal communication.

Human Communication Research, 1 (2), 99-112.

Berger, C. R., Douglas, W. 1981. Studies in interpersonal

epistemology: III. Anticipated interaction, self-

monitoring, and observational context selection.

Communication Monographs, 48 (3), 183-196.

Brown, V. R., Vaughn, E. D. 2011. The writing on the

(Facebook) wall: The use of social networking sites in

hiring decisions. Journal of Business Psychology, 26

(2), 219-225.

Caers, R., Castelyns, V. 2011. LinkedIn and Facebook in

Belgium: The influences and biases of social network

sites in recruitment and selection procedures. Social

Science Computer Review, 29 (4), 437-448.

Cann, E., Siegfried, W. D., Pearce, L. 1981. Forced

attention to specific applicant qualifications: Impact on

physical attractiveness and sex of applicant. Personnel

Psychology, 34 (1), 15-26.

Cash, T. F., Gillen, B., Burns, D. S. 1977. Sexism and

beautyism in personnel consultant decision making.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 301-310.

Chan, W., Mendelson, G.J. 2010. Disentangling stereotype

and person effects: Do social stereotypes bias observer

judgment of personality? Journal of Research in

Personality, 44 (2), 251-257.

Christofides, E., Islam, T., Desmarais, S. 2009. Gender

stereotyping over instant messenger: The effects of

gender and context. Computers in Human Behavior,

25 (4), 897-901.

Daft, R. L., Lengel, R. H. 1984. Information richness: A

new approach to managerial behavior and organization

design. Research in Organizational Behavior, 6, 191-

233.

Daft, R. L., Lengel, R. H. 1986. Organizational

information requirements, media richness and

structural design. Management Science, 32 (5), 554-

571.

Davidson, K. H., Maraist, C., Bing, M. N. 2011. Friend or

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

548

foe? The promise and pitfalls of using social

networking sites for HR decisions. Journal of Business

Psychology, 26 (2), 153-159.

Dion, K. K., Pak, A. W., Dion, K. L. 1990. Stereotyping

physicalattractiveness:Asocioculturalperspective.

JournalofCross‐CulturalPsychology,21,378‐398.

Donath, J. S. 1999. Identity and deception in the virtual

community. In M. A. Smith P. Kollock (Eds.),

Communities in Cyberspace (pp. 29-59). New York:

Routledge.

Duck, S. W. 1982. Interpersonal communication in

developing acquaintance. In G. R. Miller (Ed.),

Explorations in Interpersonal Communication (pp.

127–148). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Gibbs, J. L., Ellison, N. B., Heino, R. D. 2006. Self-

presentation in online personals: The role of

anticipated future interaction, self-disclosure, and

perceived success in internet dating. Communication

Research, 33 (2), 1-26.

Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday

Life. New York: Anchor.

Hancock, J.T., Dunham, P.J. 201. Impression formation in

computer-mediated communication revisited: An

analysis of the breadth and intensity of impressions.

Communication Research, 28 (3), 325-347.

Heilman, M. E., Saruwatari, L. R. 1979. When beauty is

beastly: The effects of appearance and sex on

evaluations of job applicants for managerial and non-

managerial jobs. Organizational Behavior and Human

Performance, 23, 360-372.

Heilman, M. E. Stopeck, M. H. 1985a. Being attractive,

advantage or disadvantage? Performance based

evaluations and recommended personnel actions as a

function of appearance, sex, and job type.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 35, 202-215.

Heilman, M. E., Stopeck, M. H. 1985b. Attractiveness and

corporate success: Different causal attributions for

males and females. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70,

379-388.

Hosada, M., Stone-Romero, E. F., Coats, G. 2003. The

effects of physical attractiveness on job-related

outcomes: A meta-analysis of experimental studies.

Personnel Psychology, 56 (2), 431-462.

Labrecque, L.I., Markos, E., Milne, G.R. 2011. Online

personal branding: Processes, challenges, and

implications. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 25 (1),

37-50.

Lee, E.-J. 2003. Effects of "gender" of the computer on

informational social influence: The moderating role of

task type. International Journal of Human-Computer

Studies, 58 (4), 347-362.

Lee, E.-J. 2004. Effects of gendered character

representation on person perception and informational

social influence in computer-mediated

communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 20

(6), 779-799.

Marlow, C. M., Schneider, S. L., Nelson, C. E. 1996.

Gender and attractiveness biases in hiring decisions:

Are more experienced managers less biased? Journal

of Applied Psychology, 81 (1), 11-21.

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L.,

Graham, M. J., Handelsman, J. 2012. Science faculty’s

subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings

of the National Academy of Science, 109, 16474-

16479.

Nowak, K. L., Rauh, C. 2008. Choose your ‘‘buddy icon’’

carefully: The influence of avatar androgyny,

anthropomorphism and credibility in online

interactions. Computers in Human Behavior, 24 (4),

1473-1493.

Oliphant, V. N., Alexander, E. R. 1982. Reactions to

resumes as a function of resume determinateness,

applicant characteristics, and sex of raters. Personnel

Psychology, 35 (4), 829-842.

Schlenker, B. R., Britt, T. W. 1999. Beneficial impression

management: Strategically controlling information to

help friends. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 76 (4), 559-573.

SHRM. 2008. Online Technologies and Their Impact on

Recruitment Strategies. Society for Human Resource

Management. Retrieved from www.shrm.org/research

SHRM. 2011. SHRM Research Spotlight: Social

Networking Websites and Staffing. Society for Human

Resource Management. Retrieved from

www.shrm.org/research

Short, J., Williams, E., Christie, B. 1976. The Social

Psychology of Telecommunications. London: Wiley.

Stangor, C., Schaller, M. 1996. Stereotypes as individual

and collective representations. In C. N.Macrae,

C.Stangor M.Hewstone (Eds.), Stereotypes and

Stereotyping. (pp. 3-37). New York: The Guilford

Press.

Stone, A. R. 1996. The War of Desire and Technology at

the Close of the Mechanical Age. Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press.

Tidwell, L. C., Walther, J. B. 2002. Computer-mediated

communication effects on disclosure, impressions, and

interpersonal evaluations. Getting to know one another

a bit at a time. Human Communication Research, 28

(3), 317-348.

Turkle, S. 1995. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of

the Internet. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Vancouver, J.B., Ilgen, D.R. 1989. Effects of interpersonal

orientation and the sex-type of the task on choosing to

work alone or in groups. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 74 (6), 927-934.

Walker, J. H., Field, H. S., Bernerth, J. B., Becton, B.

2012. Diversity cues on recruitment websites:

Investigating the effects on job seekers’ information

processing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97 (1),

214-224.

Walther, J. B. 1996. Computer-mediated communication:

Impersonal, interpersonal, and hyperpersonal

interaction. Communication Research, 23 (1), 1-43.

Walther, J. B. 1997. Group and interpersonal effects in

international computer-mediated collaboration.

Human Communication Research, 23 (3), 342-369.

Walther, J. B., Slovacek, C.L., Tidwell, L.C. 2001. Is a

picture worth a thousand words? : Photographic

LookMeintheEyeifYou'reaMan-TheImpactofGenderCuesonImpressionFormationinOnlineProfessionalProfiles

549

images in long-term and short-term computer-

mediated communication. Communication Research,

28 (1), 105-134.

Wang, S. S., Moon, S.-I., Kwon, K. H., Evans, C.A.,

Stefanone, M.A. 2010. Face off: Implications of visual

cues on initiating friendship on Facebook. Computers

in Human Behavior, 26 (2), 226-234.

Watkins, L. M., Johnston, L. 2000. Screening job

applicants: The impact of physical attractiveness and

application quality. International Journal of Selection

and Assessment, 8, 76-84.

Wells, J. D., Valacich, J. S., Hess, T.J. 2011. What signals

are you sending? How website quality influences

perceptions of product quality and purchase intentions.

MIS Quarterly, 35 (2), 373-396.

Wiliams, M. J., Mendelson, G.A. 2008. Gender clues and

cues: Online interactions as windows into lay theories

about men and women. Basic and Applied Social

Psychology, 30 (3), 278-294.Vazire, S., Gosling, S.D.

2004. e-Perceptions: Personality impressions based on

personal websites. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 87 (1), 123–132.

Zhao, S., Grasmuck, S., Martin, J. 2008. Identity

construction on Facebook: Digital empowerment in

anchored relationships. Computers in Human

Behavior, 24 (5), 1816-1836.

WEBIST2013-9thInternationalConferenceonWebInformationSystemsandTechnologies

550