Virtual Currency for Online Platforms

Business Model Implications

Uschi Buchinger, Heritiana Ranaivoson and Pieter Ballon

iMinds-SMIT, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium

Keywords: Loyalty Schemes, Virtual Currency, Business Models, Two-sided Markets.

Abstract: Since the first loyalty program was introduced in the 1980s, many sectors and industries have adopted and

configured these schemes to meet their specific requirements. But it is just recently that technological

innovation has enabled the transfer of these schemes into the online environment, and, more concretely, to

the increasing number of online platforms. Operating on two-sided markets, platforms started to deploy

loyalty programs to address customers and Third parties such as retailers or merchants alike. Additionally

they profit from the embedding in the digital environment, which enables the expansion of loyalty points to

become a Virtual Currency with the power to affect platforms’ business strategies. Based on the analysis of

four case studies, this paper focuses on the effect of the implementation of a Virtual Currency scheme on the

platforms’ organizational, financial and service business model parameters. It shows how Virtual Currency

schemes enable platforms to encourage loyalty of not only their customers but also in some configurations

of third parties, sometimes to the extent that one or both sides of the market are locked-in. Second, Virtual

Currency can be deployed as a source of revenue and thus play a role in the platform’s financial design.

1 INTRODUCTION

Since American Airlines established the first loyalty

program in the 1980s, various industries such as

hotels, retailers, financial services and leisure sectors

followed the concept of rewarding loyal customers

(O’Malley, 1998); (Palmer et al., 2000). It is

contended that this results in a positive influence on

the financial performance because of the higher

value of customer retention compared to new

customer acquisition (Christopher et al., 2008);

(Reichheld and Sasser, 1990); (Webster, 1992).

One of the most common measures is the issuing

and redeeming of company-related loyalty points

bound to a customer card which is implemented by

many industries (Wright and Sparks, 1999). Over

time loyalty programs became more and more a

standard in certain industries, which results in a loss

of its competitive advantage (Palmer et al., 2000).

While this is true for conventional businesses,

the development of Information and Communication

Technology (ICT) stimulated new industries in the

electronic business, who see a potential in the

loyalty concepts to bind customers and thus increase

the switching barriers in the online sector.

In addition, online businesses profit from the

embedding in the digital setting, where loyalty

points merge with the technology-driven rise of

digital money. Rewarded points loose their status of

simple loyalty measures to become Virtual

Currencies (VC), which have potential to change the

business’ economics. Unlike points, VC answers

multiple purposes e.g. payment methods accepted by

other Third parties and thus exceeding the sole B2C

relation.

Hence, the creator and coordinator of the VC is

on the one hand confronted with the building a

network of Third parties around the VC scheme,

while on the other hand, it aims at the original

intention of binding customers and encouraging

loyal behaviour. The purveyor can be placed as a

mediator of a two-sided market.

Platforms are already operating on two-sided or

even multi-sided markets with or without providing

own services on top of their platform activities

(Ballon, 2009); (Rochet and Tirole, 2002a). As a

platform, Rochet and Tirole (2002a) determine for

example software (videogame platforms, operating

systems), portals and media platforms or payment

systems. An essential characteristic of such markets

is that the utility for any user derived from a good or

service correlates to the number of users of this good

196

Buchinger U., Ranaivoson H. and Ballon P..

Virtual Currency for Online Platforms - Business Model Implications.

DOI: 10.5220/0004506601960206

In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Data Communication Networking, 10th International Conference on e-Business and 4th

International Conference on Optical Communication Systems (ICE-B-2013), pages 196-206

ISBN: 978-989-8565-72-3

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

or service on the other side (Varian, 2000). Hence,

platforms (acting as intermediates) need to take care

of both sides in an equivalent way. The choice of the

business model is of utmost importance. Many

platforms follow the strategy of treating the two

sides differently, e. g. while one side of the market is

included for free - or is even incentivized to join -

the other side, who is interested in getting access to

the former, needs to pay (Rochet and Tirole, 2002a).

VC, which emerges from loyalty concepts but

addresses financial aspects likewise, has potential to

address both sides of the market simultaneously.

This paper will, by the analysis of four case

studies, focus on the configuration of such VC

concepts by online platforms that operate on such

two-sided of the market. This include customers on

the one hand and Third parties on the other hand.

Contrasting conventional loyalty schemes, little

research is conducted to examine how VC schemes

can affect platforms’ business models in order to

meet the two-folded objectives of online platforms,

namely to encourage loyalty (or lock-in) and open

revenue streams on one or both sides of the market.

Against this backdrop, VC strategies are thus

examined primarily upon their impact on financial

and service design parameters while also reaching

out to give insights to the organizational design via

representative value networks.

In the remainder of the paper, Section 2

describes the applied business model methodology.

Section 3 explains how platforms have taken over

loyalty points schemes invented and implemented by

various organizations. Section 4 describes in detail

how VC has been implemented in four case studies

describing the organizational design by the means of

representative value networks; Section 5 analyses

the impact of such an implementation on two further

business model parameters, the service and financial

design aspects. It thus focusing specifically on the

revenue sharing model and the loyalty concept.

Section 6 concludes and suggests ways for further

research.

2 METHODOLOGY

This paper adopts the methodology of business modelling

in order to analyse disperse interests of actors in a value

network, their respecting resources, roles and

relationships. The authors rely on the framework

developed a.o. by Ballon (2007) and Braet and Ballon

(2007), providing an holistic approach for examination of

network architectures. They define the business modelling

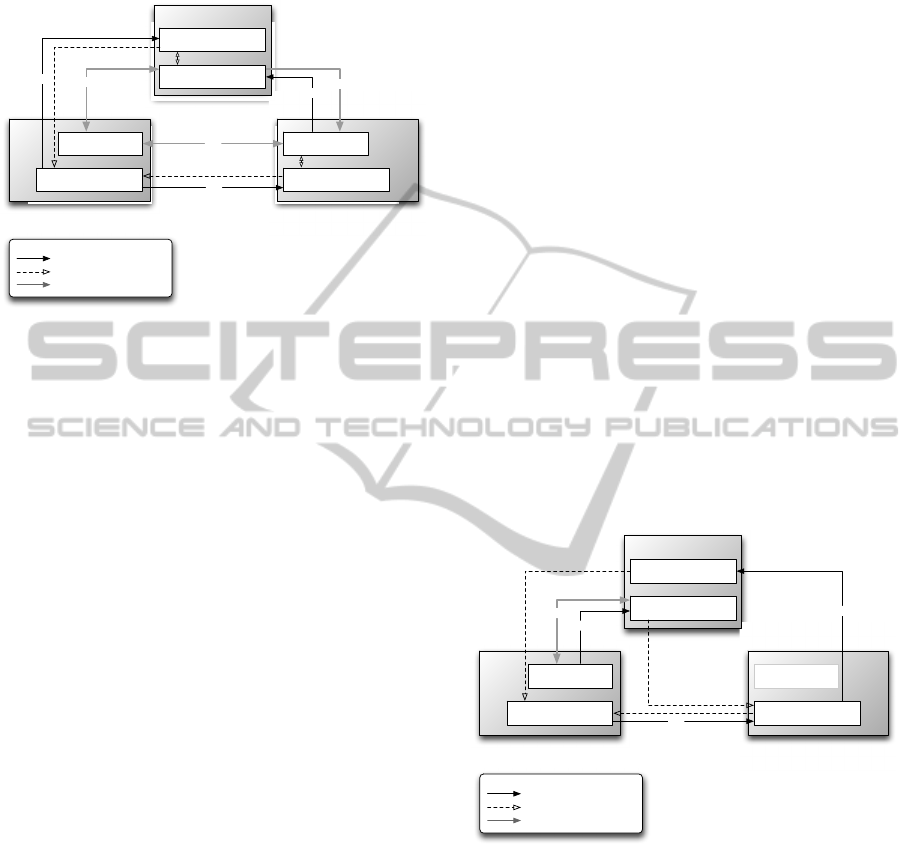

cycle as consisting of four parameters (see Figure 1):

organization, technology, service and finance. The

organization design corresponds to the Value network, i.e.

a framework consisting of business actors (physical

persons or corporations mobilizing tangible or intangible

resources), roles (business processes fulfilled by one or

more actors with according capabilities), relationships (the

contractual exchanges of products or services for financial

payments or other resources). The technology design

includes aspects such as modularity, distribution of

intelligence and interoperability (the technology design is

taken as granted and therefore considered with less details

in this paper). The service design refers to the intended

customer value. Finally, the finance design includes issues

related to costs and revenues.

Besides the focus on the impact of VC on the

business model parameters, the product/service offer

by the platform and Third party is taken into

consideration and linked to the VC scheme.

Figure 1: The business model cycle (Source: Braet and

Ballon, 2007).

3 DEVELOPMENT OF VIRTUAL

CURRENCY SCHEMES BY

PLATFORMS

3.1 Platforms’ Role between Customer

and Third Party

ICT markets are characterized by far-reaching

platformisation (Ballon, 2009). A platform can be

defined as a product, technology or service that is an

essential building block upon which an ecosystem of

firms can develop complementary products or

services (Gawer and Cusumano, 2002). In ICT

markets, crucial gatekeeper roles and functionalities

are often conducted by platform leaders. Various

2. TECHNOLOGY DESIGN

products & services creation

3. SERVICE DESIGN

creating customer value

1. ORGANIZATION DESIGN

mobilizing resources and

capabilities

4. FINANCE DESIGN

creating shareholder value

Leveraging resources

and capabilities

Products/service

brought to market

Resource

redistribution for

internal development

Appropriating

financial value

Consumers Consumer Groups

EXTERNAL STAKEHOLDERS

EXTERNAL ACTORS

Competitors

Suppliers

PUBLIC DOMAIN

Government, Standardizing bodies, Societal resources & institutions...

VirtualCurrencyforOnlinePlatforms-BusinessModelImplications

197

business models have emerged that help them to

exercise a form of control over the wider network,

and to add and capture significant value in the

process.

An essential characteristic of platforms is their

operation on two-sided markets. Two-sided markets

exist as soon as the utility of any customer A is

correlated to the number of customers B. These

models were first applied to credit card markets

(Rochet and Tirole, 2002b). Actually on such

markets, the higher the number of credit card

holders, the more interesting it becomes for the

shops to be equipped with devices that allow to pay

by card. Conversely, the higher the number of

equipped shops, the more utility one cardholder

derives from having such a card (Borestam and

Schmiedel, 2011).

The value network can thus be broken down to

three actors, represented in Figure 2, building the

base of each case study: the platform, which purveys

VC, the customer and the Third party. The platform

facilitates the interactions between both sides.

Relations are displayed as arrows between the

actors. In the following figures, three forms of

arrows will be depicted: black lines indicate

financial streams; dotted lines indicate

product/service streams (selling and receiving of

products or services), grey lines depict the VC

stream. Relations are bidirectional (exchange

between actors) or monodirectional (from one actor

to another).

Figure 2: A stylised representation of Two-sided markets.

Rochet and Tirole (2002a), examining the financial

relation between the actors of a two-sided market,

derive that many platforms choose either side for

revenue generation. One side of the market is then

treated as a profit centre that concurrently needs to

cover the loss (or financial neutrality) that is

accepted for the other side of the market.

It is hence a balancing act of generating revenue

and attracting and keeping stakeholders (concretely

encourage loyal behaviour or even enforce it by

locking stakeholders in). Especially in the online

environment, which is characterized by its low

switching costs (Shimizu, 2012) and the culture of

free services (Anderson, 2009), addressing this

objectives is still difficult and drives the need to find

new concepts.

3.2 From Loyalty Schemes to Virtual

Currency

The paper follows Sharp and Sharp’s (1997)

definition of loyalty program as “structured

marketing efforts which reward, and therefore

encourage, loyalty behaviour” (Sharp and Sharp,

1997, p. 474). Different types of rewards have been

developed throughout B2C sectors, notably the

implementation of incentives such as points that are

redeemable for rebates or prizes within the loyalty

scheme (Dowling and Uncles, 1997); (Sharp and

Sharp, 1997). Organizations implement according

measures to acquire competitive advantages. Such

programs however might become a standard,

diminishing the competitive edge of rewards

(Palmer et al., 2000).

One possibility to counteract this tendency is to

expand the industries or brands participating in the

loyalty program, a method pioneered once again by

various airlines. The cooperation scheme, defined

also as coalition loyalty or cross loyalty, describes

the facilitation of members’ loyalty cards at multiple

- sometimes competing - retailers. For the customer,

every industry or brand in the network adds

incentives for the customer to join (Baird, 2007).

While Baird (2007) refers particularly to the card

as the most common form of a rewarding design,

multiple approaches have arisen that changed the

establishments in the sector. An important trend is

the rise of applications allowing customers the

online coordination of loyalty programs.

Applications can have all necessary functionalities

to make a physical loyalty card obsolete. Hence,

platforms are developing adequate systems for

points collection and storage (Perez, 2012). At the

same time, they profit from the technology-driven

emergence of digital money which makes it possible

to treat loyalty points like a currency embedded in

the virtual setting. The European Central Bank

defines Virtual Currency as “unregulated, digital

money, which is issued and usually controlled by its

developers, and used and accepted among the

members of a specific virtual community”

(European Central Bank, 2012, p. 13) While this

definition raises the impression, that the community

is only the customer, in this paper it consists of both

sides of the market (customers and Third parties).

Customer

Platform

Third party

Financial or

Service flows

Legend

ICE-B2013-InternationalConferenceone-Business

198

Nevertheless, VC acts, like plain loyalty points,

as a loyalty measure towards customers by binding

them to this particular currency (and hence the

related organization). But while pure loyalty

programs are mainly implemented to reward

customer behaviour (Kumar and Shah, 2004),

Virtual Currency allows several uses, i.e. they are

tools for multiple usage options granted to the

different types of stakeholders in the Value network.

VC thus differentiates from conventional loyalty

concepts insofar as it can, besides binding customers

to the organization, have the same incorporating

effect on Third parties.

It is thus essential that the VC circulates in the

entire Value network. This can be ascribed to

whether Virtual Currency leaves a partner’s account

(i.e. a partner issues VC) enters the account (i.e. the

actors get VC) or fulfils tasks in the account.

Following options emerge:

Sell: Issuing VC in exchange of conventional

money,

Reward: Issuing or awarding VC,

Redeem: Taking back VC, i.e. accepting it as a

payment,

Create: build up and coordinate the network

around a VC,

Buy: Purchase VC for conventional money,

Spend: Using VC as a payment instrument

instead/alongside conventional money,

Get rewarded: Conduct a (qualifying) activity

that is awarded with VC,

Store: Accumulating and saving VC in personal

accounts or wallets.

Some roles can be performed by only one type of

actor in the network while others can be performed

by two or more types of actors. This paper assumes

certain preconditions: i) The creator of the VC is in

all cases represented as the platform. It manages and

coordinates the VC as well as the customer base and

user accounts and intermediated the two sides of the

market; ii) only the customer gets rewarded and

stores VC. Therefore customers need to create a

customer account on the platform; iii) Third parties

encompass all entities that sell products or services

by the means of the platform and are included in the

VC insofar as that they can either buy, reward,

redeem or sell the VC.

The exact configuration of the relationships

(organization design) and its impact on the

platform’s financial and service design will be issue

of the succeeding analysis.

4 VC IMPLEMENTATION

IN PLATFORM

SCHEMES – FOUR CASES

The section provides a detailed study of four cases

of platforms that have implemented a Virtual

Currency approach. They were selected based on

their different implementation strategies of VC and

thus the multiple options ascribed to VC

implementation that they represent. The diversity of

the actors, and their related business models, that

adopted such VC allows to draw conclusion based

on a broad view: Miles & More, Groupon Bucks,

Facebook Credits and Mobile Viking Points.

All value networks are reduced to three actors:

platform, Third party and customer. Each actor

fulfils certain roles that emerge from its daily

operations plus additional roles that emerge from the

implementation of a VC in the network. They are

illustrated as white boxes in the following value

networks and are reduced to two representative roles

for each actor: a role for product/service operations

(platform and Third parties provide products and

services, customers receive them) and VC operations

(platform creates and manages the VC, Third parties

and customers participate in the scheme). The exact

construction will be explained in a narrative way and

subject to a detailed analysis.

Relationships are displayed as arrows in the

value network including i) financial flows, ii)

product/service flows iii) Virtual Currency flows.

VC flows will also represent whether an actor

receives VC (i.e. customer gets rewarded, Third

parties buy or redeem and the platform redeem the

VC) or issues VC (i.e. customer spends VC, Third

parties and platform reward or sell VC)

The analysis of the relationship thus takes into

account: the exchange of money for products/

services, the exchange of money for VC, the

exchange of VC for products/services.

4.1 Miles

The native intention of the Miles & More program

implemented by the German airline Lufthansa is to

raise customer loyalty towards the airline while the

extension of the VC to Third parties increases its

value for customers. The platform targets both sides

of the market: Miles are rewarded to the customer

and sold to Third parties (e.g. banks, retailers,

hotels) Miles are only valid 36 month of the date of

accrual (e.g. date of flight) and expire at the end of

the respective quarter (Miles and More, n.d.). In

VirtualCurrencyforOnlinePlatforms-BusinessModelImplications

199

2011, 20 million members from 234 countries

participated in the program, with 250 partners

(Lufthansa, 2011). Figure 3 illustrates the relations.

Figure 3: Miles and More Value network.

Miles & More as well as Third parties offer

products/services for selling to the customer. Money

flows from the customer to either representative role

and creates a product/service flow back (e.g. for the

receipt of a travel ticket). A purchase initiates the

rewarding of VC (arrow from product/service

provision to VC creation respectively VC program

participation and reverse: the VC can be redeemed

for products/services). The VC stream is

bidirectional between platform and customer and

customer and Third party (both partners can reward

and redeem the VC) and monodirectional between

the platform and Third parties. Third parties need to

have some form of payment agreement with the

platform (black arrow) to receive the VC that they

can reward (Mason and Barker, 1996). The

relationship between the three entities is as followed:

Platform/Customer: The primary intention of the

VC program is to reward VC to (and redeem VC

from) customers for purchases of flights. This results

in an indirect income stream for the platform –

indirect since it is unattached to the direct purchase

of miles. Customers’ purchased miles, unlike

rewarded ones, can solely be used for an immediate

redemption in form of a flight or service provided by

the airline (not by a Third party). Given the

divergent characteristics, purchases of miles are not

exposed as a possibility for the customer in the table.

Participation in the program is free for the customer,

but he/she is needs to set up a customer account.

Platform/Third Party: The platform cedes

control to Third parties by giving allowance to

reward and redeem miles. The platform generates

revenue directly by selling the VC for every mile

that the Third party rewards.

Third Party/Customer: Third parties conduct the

same rewarding process as the platform making use

of the VC acquired from the latter. They are mainly

unrestricted in their decisions upon applying terms

and conditions for rewarding (e.g. one mile for every

Euro spend on a purchase). A risk for the platform is

that none of the gathered miles are redeemed for a

ticket-purchase but merely for partner’s services.

4.2 Groupon Bucks

Groupon Bucks, executed by the group-buying

platform Groupon, solely reinforce customers’

loyalty. Groupon is an online platform that allows

Third parties to sell own products and services to

customers at a discounted price that can be set by the

means of economies of scale emerging form group

buying. Registered customers are given the

possibility to subscribe for offers that are validated

once enough customers have subscribed. Financial

movements pass via the platform. For its service,

Groupon retains a certain amount from each deal

sold but does not charge the customers to create their

customer accounts. Customers receive products or

services directly from the Third party. Groupon

Bucks do not expire (Groupon, 2012).

Figure 4: Groupon Value network.

The description of the figure is done in the following

analysis of the bilateral relations:

Platform/Customer: The platform offers its free

online service to the customer but does not have own

products for sale (dotted arrow from product/service

provision to receipt by the customer). The

implemented VC encourages solely interactions

between customers and the platform. A customer

who has performed, or participated in, a qualifying

user activity (e.g. referring someone to Groupon

who then conducts a purchase on the platform) are

rewarded with Groupon Bucks. The VC can be

Miles and More

Product/Service flow

Financial flow

Legend

€

Virtual Currency flow

VC

€

Product/Service receipt

VC program

participation

Product/Service

provision

VC creation/

management

VC program

participation

Product/Service

provision

Third party

Customer

VC

VC

€

Groupon

Product/Service flow

Financial flow

Legend

€

Virtual Currency flow

VC

€

Product/Service receipt

VC program

participation

Product/Service

provision

VC creation/

management

VC program

participation

Product/Service

provision

Third party

Customer

€

ICE-B2013-InternationalConferenceone-Business

200

redeemed for any deal at the platform. Additionally,

Bucks can be bought in form or gift cards as

presents for other customers. The redemption of the

Virtual Currency can however only pertain Third

party products/services, facilitated by the platform

(dotted line between the VC creation/management

and product/service provision of the Third party).

Platform/Third Party: The platform serves as a

mere sales channel for Third parties’ offers, not

providing services or products itself. The revenue

model consists of a fee taken by the platform on

every deal made by a Third party but yet unrelated

to the VC.

Third Party/Customer: Products/services can be

bought by the means of the platform; the VC does

not affect their relationship.

4.3 Facebook Credits

Facebook Credits, the platform’s Virtual Currency,

answer the purpose as loyalty measure towards

Third parties but moreover creates as a source of

revenue since the customers are charged for the

receipt of the VC. Credits are studied in this paper in

the case of game applications. Launched in 2004, the

free platform Facebook gathered more than 1 billion

active users in 2012. Since 2007, Third party

developers are able to provide apps, including

games, usable via the platform (The Associated

Press, 2013) while Facebook offers support in terms

of monetizing strategies. Together with the partner

company TrialPay, Facebook has implemented a

mechanism to rewarding customers for conducting

qualifying user activities (e.g. completing advertiser

offers). Credits are subject to expiration, which takes

effect when they are not used for three years. The

platform my redeem the VC for activities on behalf

of the user (sending virtual gifts to friends) or

donating it to charity. Standard redemptions fees are

however charged. Facebook Credits’ use is

constantly evolving. The paper works with the terms

and conditions of Facebook credits they were in

place in 2011/2012 (Facebook, 2013a); (Facebook,

2013b).

Platform/Customer: Facebook’s service

provision consists of the facilitation of Third party

services that can be uses via the customer accounts.

Within the game set-up, purchases of virtual in-

game items are supported, demanding however the

utilization of VC, that a customer stores in his game

items from Third party games, the actually need to

have a sufficient amount of Credits.

Figure 5: Facebook Value network.

Therefore, the customer must purchase the credits

(money stream from the VC participation to VC

creation/management and a VC flow back). The VC

cannot be redeemed at the platform itself. Besides

conscious, provident purchase of VC preliminary to

playing, it is possible to buy Facebook Credits whilst

playing when the account is not sufficiently filled.

Again Facebook Credits are bought, which are then

automatically converted into the requested item or

in-game currency. In other words, customers think

they buy the Third party’s currency whilst actually

buying Facebook Credits. Facebook thus creates a

direct revenue stream from the customer.

Platform/Third Party: While the platform creates

and operates the main service offer for the

customers, for the gaming applications it relies

mainly on the enrichment of assets via Third parties.

The platform empowers and supports Third parties

in the development of game applications and

embedding of payment mechanisms. Through the

implementation of Credits, an obligatory payment

method for gaming, Facebook has introduced loyalty

measures towards Third parties. Payments are

collected from customers. For each transaction,

Facebook credits Third parties with the proceeds

from the sale minus their service fee of 30 % + any

applicable tax (Facebook, 2013b); (Kincaid, 2011).

A partner company of Facebook enabled a

rewarding mechanism that allows Third parties to

award qualifying user activities with Facebook

Credits.

Third Party/Customer: The compulsory VC

scheme locks in game developers who want to

address and sell in-game items to the customer base

of Facebook. Customers are locked-in likewise since

they can solely purchase Third party in-game items

via Facebook Credits.

Facebook

Product/Service flow

Financial flow

Legend

€

VC

Virtual Currency flow

VC

€

Product/Service receipt

VC program

participation

Product/Service

provision

VC creation/

management

VC program

participation

Product/Service

provision

Third party

Customer

VirtualCurrencyforOnlinePlatforms-BusinessModelImplications

201

4.4 Mobile Viking Points

The MVNO (mobile virtual network operator)

Mobile Vikings implemented Viking Points as a

loyalty measure towards their customers who are

included for free in the VC program. Additionally

they incite Third parties to use this VC thus

contributing to customer loyalty towards both,

themselves and the platform. Active in Belgium and

the Netherlands, Mobile Vikings counts 160.000

members whom they sell mobile services such as

call minutes, SMS and data packages on Viking SIM

cards. The Viking Points can be exchanged in these

mobile services. Mobile Vikings additionally

operates a service to register Third party locations

(thus creating a ”Spot”). The location is thereupon

shown on a virtual map to all customers of Mobile

Vikings, with possibly related deals made available.

Information is missing about an expiration data.

Since it is however mentioned, that the customer is

free to use the VC whenever he wants, it can be

assumed, no expiration date is set (CityLive NV,

2012); (Mobile Vikings, 2013a), (Mobile Vikings,

2013b).

Figure 6: Mobile Vikings Value network.

Platform/Customer: Comparable to Miles & More,

Mobile Vikings offer products/services for their

customers (depicted as a money flow from the

customer in return for the products/services).

Regarding the VC, Viking Points set up a reward

mechanism for certain qualifying user activities (e.g.

convincing someone to join Mobile Vikings).

Optionally they can be bought in form of gift cards

mainly as a present for other users. Rewarded points

are redeemable for services/products of the platform

Mobile Vikings (bidirectional stream from the

platform to the customer).

Platform/Third Party: Solely the platform

provides the services/products that customers get in

exchange for the VC, i.e. its various mobile services.

Mobile Vikings however provides to Third parties

the possibility to gratis register venues such as shops

and stores on their virtual map. In addition, Mobile

Vikings runs a business-focused product bundle for

€ 375 (VAT incl.) per year, permitting Third parties

to create deals connected to the ”Spot”. Such deals

aim at attracting customers due to price cuts and

rebates on products. Third parties buy this tool from

the platform for their own product/service provision

(money stream from Third party’s product/service

provision and a respective service/product stream

back). With the product bundle, Third parties also

receive 3000 Viking Points that they are asked to

reward their customers with every concluded deal

(illustrated as a VC stream from the VC

participation of the Third party to the customer in

the illustration). The Third party decides upon the

height of the rebate and the volume of points

rewarded for each deal. Third parties have even

options to purchase further Viking Points for their

rewarding intentions. Mobile Viking charges then

the price for the VC plus 25% (CityLive NV, 2012).

Third Party/Customer: Third parties expand their

options with the purchase of the product bundle like

the localization and coordination of “Spots” (i.e.

shops and stores) and the creation of deals that the

customers can conduct. Third parties decide upon

the creation and exact configuration of deals. They

are obliged however to issue VC with every deal

conducted by customers.

5 VIRTUAL CURRENCY’S

IMPACT ON THE PLATFORMS’

BUSINESS MODEL

The section compares the cases studied previously to

analyse the impact of Virtual Currency on business

model parameters. The cases were chosen for their

coverage of divergent VC strategies and the disperse

sectors they are operating in. Consequently, general

conclusions are not possible. The analysis however

allows identifying of a few trends and issues that

affect the use of loyalty schemes and VC. The focus

thereby will be put on the financial- (revenue

generation and -sharing models) and the service

design aspect (strengthening of loyalty or even lock-

in on one or both sides of the market) whereas the

organizational design can be derived implicitly from

the value networks and are only described

superficially. The business model cycle of Ballon

(2007) and Braet and Ballon (2007) is used, which

Mobile Vikings

Product/Service flow

Financial flow

Legend

€

Virtual Currency flow

VC

€

Product/Service receipt

VC program

participation

Product/Service

provision

VC creation/

management

VC program

participation

Product/Service

provision

Third party

Customer

VC

VC

€

€

€

ICE-B2013-InternationalConferenceone-Business

202

consists of a further parameters, namely the

technology design. This aspect for the

implementation of VC is considered as given and

won’t be part of the analysis.

Seven characteristics are subject to comparison.

They can directly be linked up to one or more

business model parameters: the side(s) of the market

on which the VC is oriented; whether the platform

itself provides goods or services for which the VC

can be redeemed; the strength of enforcement to use

the VC in the network; whether Third parties also

redeem the VC; if the scheme rewards customer; if

the platform generates revenue by selling the VC

and if the VC has an expiration date (financial

design). For the second last point, a trade-off is

necessary between the Third parties (T.P.) and

customers (Cust.). Table 1 depicts an overview on

which characteristics are ascribed to which business

model parameters and their respective executions in

the various use cases.

Before the analysis of each parameter can be

made, this paper already revealed a general increase

in the range of roles that accompanies the

implementation of a VC stream. Expanding plain

loyalty points, VC circulation is subject to selling,

rewarding, redeeming, creating, buying, spending,

getting rewarded and storing by one or more actors

in the value network.

Regarding the organization design, one aspect is

the opening of the system to both sides of the

market. It is described as Orientation of the VC

scheme: two-sided signifies the issuance of VC

(rewarding or selling) to both sides of the market:

customers and Third parties. It applies to all cases

except of Groupon. Groupon Bucks addresses solely

the customer side but does not incorporate Third

parties in the scheme. With this limited possibilities,

loyalty through the VC is enforced on the customer

side only. The other examples are oriented on both

sides of the market, which means that the platform

needs to make a trade-off between each party’s

interests. As a result it will favour one side over the

other and thus enforce loyalty one side more. The

expansion of one side (e.g. by benefits such as free

participations or incentives) is normally an argument

to encourage the second side to join – wherefore

(payment) conditions are set. Miles & More and

Mobile Vikings initialize demand for the VC

primarily on the customer-side (free participation)

and charges the Third party. Facebook targets

principally the Third parties to implement the VC

standards (free help and support for the

implementation) and asks the customers to pay.

Multifaceted redemption describes the possibility

to redeem points at the platform as well as the Third

parties. Variety can be given throughout industries

(e.g. Third parties can be supermarkets, hotels, car

rentals, etc.) or within such (e.g. different execution

of games for Facebook). Each actor who redeems

the VC adds value to the loyalty scheme for the

customer but bears the risk that the customer does

not spend money (and shop) at the platform.

Platforms with their own products/services profit

from a system where VC, once issued, can only be

redeemed in their respective stores but limit the

choice for the customer. Consequently, platforms

need to make a trade-off between single (here:

Mobile Vikings and Groupon), or multifaceted

redemption places (Miles and More, n.d; Facebook).

The second aspect of the organization and

service design is the enforcement to use the VC in

the network. It is weak when no obligations are set

for the usage and participation is optional (Miles and

More, n.d; Groupon). In case of obligations, they

can affect both sidesb(Facebook) or one side

(Mobile Vikings) of the market. Facebook

Table 1: Characteristics of business model strategies.

Miles and More Groupon Facebook Mobile Vikings

Organization design

Orientation of the VC

scheme

two sides one side two sides two sides

Organization and

service design

Multifaceted

redemption

Y N Y N

Enforcement to use

VC

Weak Weak

Strong towards both

sides

Strong towards

Third Parties

Service design

Platform provides

services/products

Y N Y Y

Option of rewarding

Cust.

Y Y Y Y

Financial design

Direct Revenue

Platform

T.P. Cust. T.P. Cust. T.P. Cust. T.P. Cust.

Y N N Y N Y Y Y

Expiration Y N Y N

VirtualCurrencyforOnlinePlatforms-BusinessModelImplications

203

developers need to use the payment schemes if they

want to sell virtual items while customers must use

the VC for purchases. Mobile Vikings’ Third parties

are obliged to reward the VC to every customer for a

purchase. The latter can however buy products/

services from the platform for conventional money

alike.

A characteristic of the service design is the

platform proposition. Two types of platforms can be

distinguished depending on whether they have their

own products/services to exchange for the VC on

top of the platform activity. Miles & More, and

Mobile Vikings (who have their own products) are

independent of Third parties’ performance. Their

VC is still valuable for the customer without the

other side of the market. The VC of the latter

(Groupon and Facebook) has only as much value as

the Third parties (various types of merchants and

game providers) create. The platform is thus

dependent on the Third parties’ capacity and

willingness to fulfil their engagements. If Third

parties fail to meet the customer demands, the VC

looses its value.

A second characteristic of the service design is

the aspect of rewarding customers for desired user

actions. It remains a central point in the

implementation of VC strategies and presents a

consistency throughout all cases. This aspect shows

the connection to the initial loyalty schemes that aim

in building-up a (long-term) customer relationship.

Influencing the financial parameter, VC can

constitute a direct source of revenue for some

platforms. In general, platforms choose either side of

the market for creating revenue with the VC while

stimulate the other side via free (or even

incentivized) participation and benefits. In the above

cases it is the case for Miles & More and Mobile

Vikings that charge Third parties for the purchase of

VC and thus build the source of revenue for the

platform. Third parties need to compensate the

”loss” e.g. by additional sales. Facebook directly

sells the VC to customers as the only way of

receiving products/services from the Third parties.

For other platforms (here: Mobile Vikings and

Groupon) the option is given to buy VC in form of

gift cards or vouchers but it is not obligatory to use

them in order to receive products/services. Miles &

More allows customers to buy additional miles only

under the restriction that they are used for flights or

services that are provided directly from the airline.

Miles & More and Mobile Vikings allow Third

parties in fact to decide on conversion rates and

terms and conditions for rewarded VC, nonetheless,

Third parties are not allowed to sell VC (and

generate revenue).

A second parameter that affects the financial

design is the expiration date. Unused VC that

expires does not require an exchange in

products/services from the platform or Third party

and thus represents income for the respective

business without service in return. Miles & More

and Facebook implemented expiration dates, both

setting a valid period of three years before the

implemented terms and conditions take effect.

The counterpart of using VC as a source of

revenue is nevertheless that it can slow its adoption

process by Third parties or customers. The higher

the fee (e.g. per transaction using VC), the less

interesting for the customer to use the VC.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This paper uses the business model approach

developed a.o. by Ballon (2007) and Braet and

Ballon (2007) to draw conclusions upon the impact

of a Virtual Currency implementation on a

platform’s business features. It focuses particularly

on the organizational, financial and service design

parameters. Concretely, the paper has examined in

how far a Virtual Currency strategy is implemented

as a solution for two challenges that platform

concepts are confronted with in the online

environment, namely (i) how to attract and retain

stakeholders when switching costs tend to be at a

minimum and (ii) how to open new revenue streams.

Starting from conventional loyalty points, the

paper first has showed their adaptation to digital

requirements and expansion of functionalities. This

lays the ground for the transformation into a Virtual

Currency. VC answers in its basic functionalities the

same purposes as loyalty points. It rewards

customers and thereby binds them to a particular

platform. However, VC exceeds that by expanding

its roles for wider range of usage options than plain

loyalty points, namely selling, rewarding,

redeeming, creating, buying, spending, getting

rewarded and storing.

The paper has analysed four case studies’ value

networks: Miles & More, Groupon Bucks, Facebook

Credits, and Mobile Viking Points. Each value

network can be reduced to three actors: the platform,

customers and Third parties (i.e. partners that sell

products or services by the means of the platform).

Certain preconditions were assumed, such as the

platform as the creator and coordinator of the VC

and responsible party for the customer base. Third

parties and customer are involved twofold in the

ICE-B2013-InternationalConferenceone-Business

204

value network: on one hand in the operations of the

selling and purchasing process of conventional

products/services. On the other hand, they are

included in the VC scheme of the platform.

The four case studies were compared along

seven characteristics that are directly linked to the

organization-, service and financial design of

business models: (i) the side(s) of the market on

which the VC is oriented; (ii) whether the platform

itself provides goods or services for which the VC

can be redeemed; (iii) the strength of the

enforcement to use the VC in the network; (iv)

whether Third parties also redeem the VC; (v) if the

scheme rewards desired customer behaviour; (vi) if

and from which side of the market the platform

generates revenue by selling the VC; (vii) and if an

expiration date is introduced that can build another

income stream for the platform.

Each case follows a different strategy concerning

the implementation of VC. One consistency is

however, the purpose of strengthening loyalty

towards the platform on one or both sides of the

market. VC can be used as a tool to locked-in Third

parties and customers and thus discourage them

from switching to competitors. The realization

ranges from weak measures, where VC is handled as

benefit or bonus program, to strong measures where

loyalty is enforced by setting usage obligations in

the network.

Second the analysis revealed that all platforms

use the VC as a source of revenue, albeit to a

different extent. Purchasing VC can either be an

additional option granted to customers (besides

rewarding) or obligatory for customers or Third

parties. In line with the two-sided market theory, in

the examples where both sides are included, revenue

is generated on one side of the market while the

other one is included for free (with the option to buy

VC made available as incentive).

Although many more factors influence the

success of a platform’s business model, it can be

concluded that VC has the necessary attributes to

support platforms strategies in their service and

financial designs by encouraging loyal behaviour (or

even enforcing it by locking stakeholders in) and

opening a source of revenue for the platform.

The authors acknowledge that industries are still

in an early phase of experimenting with new

business models concerning VC strategies, in

particular with mobile devices opening up new

possibilities such as the broader use of location-

based services. Further research is thus required

reflecting the development of the market, also from

a technical point of view.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CoMobile is an R&D project cofunded by IWT

(Agentschap voor Innovatie door Wetenschap en

Technologie), the government agency for innovation

by science and technology founded by the Flemish

Government. Companies and organizations involved

in the project are C2P – ClearPark, Alcatel-Lucent,

Netolog, CityLive – Mobile Vikings, Colibri,

Belgian Direct Marketing Association,

K.U.Leuven/COSIC, K.U.Leuven/CUO,

K.U.Leuven/ICRI, UGent/MICT, iMinds/iLab.o.

REFERENCES

Anderson, C., 2009. Free: The Future of a Radical Price,

Random House. London.

Baird, N., 2007. Coalition Loyalty programs: The next big

thing? Chain Store Age, 83(7), 14.

Ballon, P., 2007. Business modelling revisited: the

configuration of control and value. Info, 9(5), 6–19

Ballon, P., 2009. The Platformisation of the European

Mobile Industry. Communications & Strategies, (75),

15–33.

Borestam, A., Schmiedel, H., 2011. Interchange Fees in

Card Payments. ECB Occasional Paper No. 131

Retrieved from URL: SSRN: http://ssrn.com/

abstract=1927925 (accessed 26.11.2012)

Braet, O., & Ballon, P., 2007. Business Model Scenarios

for remote management. Journal of Theoretical and

Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 2(3), 62–79.

Christopher, M., Payne, A., & Ballantyne. D., 2008.

Relationship Marketing. Oxford: CRC Press.

CityLive NV, 2012. Viking Spots. URL: https://

vikingspots.com/en/ (accessed 6.2.2013)

Dowling, G. R., & Uncles, M., 1997. Do customer loyalty

Programs really Work? Sloan management review,

38, 71–82.

European Central Bank, 2012. Virtual Currency Schemes,

European Central Bank. Frankfurt am Main.

Facebook. 2013a. Facebook Sign Up. URL:

https://www.facebook.com/ (accessed 6.2.2013)

Facebook. 2013b. Facebook Developers. URL:

http://developers.facebook.com/ (accessed 6.2.2013)

Gawer, A., & Cusumano, M. A., 2002. Platform

Leadership: How Intel, Microsoft, and Cisco Drive

Industry Innovation. Boston: Harvard Business

Review Press, 1

st

edition

Groupon, 2012. Groupon. URL: http://www.groupon.com

(accessed 26.7.2012)

Kincaid, J., 2011. Facebook To Make “Facebook Credits”

Mandatory For Game Developers (Confirmed).

TechCrunch. URL: http://techcrunch.com/2011/

01/24/facebook-to-make-facebook-credits-mandatory-

for-game-developers/ (accessed: 31.10.2012)

Kumar, V., and Shah, D., 2004. Building and sustaining

VirtualCurrencyforOnlinePlatforms-BusinessModelImplications

205

Profitable Customer Loyalty for the 21st Century.

Journal of Retailing, 80(4), 317–330.

Lufthansa, 2011. Lufthansa Press Releases. Miles &

More: 20 million members. Press release archive.

URL: http://presse.lufthansa.com/en/news-releases/

singleview/archive/2011/february/11/article/1875.html

(accessed 3.7.2012)

Mason, G., & Barker, N., 1996. Buy now fly later: an

investigation of airline frequent flyer programmes.

Tourism Management, 17(3), 219–223.

Miles and More, (n.d.). Miles & More.

URL: http://www.miles-and-more.com/online/portal/

mam_com/de/homepage (accessed 6.2.2013)

Mobile Vikings, 2013a. Home. URL: https://

mobilevikings.com/bel/en/ (accessed 6th February

2013)

Mobile Vikings, 2013b. What are Viking Points? URL:

https://mobilevikings.com/bel/en/vikingpoints/

(accessed 6.2.2013)

O’Malley, L., 1998. Can loyalty schemes really build

loyalty? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 16(1),

47–55.

Palmer, A., Mcmahon-Beattie, U., & Beggs, R., 2000.

Influences on loyalty programme effectiveness: a

conceptual framework and case study investigation.

Journal of Strategic Marketing, 8(1), 47–66.

Perez, S., 2012. PassRocket Lets Any Business Create

Loyalty Cards For Apple’s New Passbook App For

Free. TechCrunch. URL: http://techcrunch.com/

2012/09/19/passrocket-lets-any-business-create-

loyalty-cards-for-apples-new-passbook-app-for-free/

(accessed 2.10.2012)

Reichheld, F. F., & Sasser, E. W., 1990. Zero Defections:

Quality Comes to Services. Harward Business Review,

14(3), 497–507.

Rochet, J.-C., & Tirole, J., 2002a. Platform competition in

two-sided markets. Journal of the European Economic

Association, 1(4), 990–1029.

Rochet, J.-C., & Tirole, J., 2002b. Cooperation among

Competitors: Some Economics of Payment Card

Associations. The RAND Journal of Economics,

33(4), 549–570

Sharp, B., & Sharp, A., 1997. Loyalty programs and their

impact on repeat-purchase loyalty patterns.

International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14(5),

473–486.

Shimizu, K., 2012. The Cores of Strategic Management,

Routledge. New York.

The Associated Press, 2013. Hits and misses in Facebook

history over the years. The Big Story. URL:

http://bigstory.ap.org/article/hits-and-misses-facebook-

history-over-years (accessed 3.2.2013)

Varian, H.R., 2000. Introduction à la microéconomie. De

Boeck Université, Bruxelles, 4

th

edition.

Webster, F. E., 1992. The Changing Role of Marketing in

the Corporation. Journal of Marketing, 56(4), 1.

Wright, C., Sparks, L., 1999. Loyalty saturation in

retailing: exploring the end of retail loyalty cards? In

International Journal of Retail & Distribution

Management, 27(10), 429–440.

ICE-B2013-InternationalConferenceone-Business

206