Detecting and Explaining Business Exceptions for Risk Assessment

Lingzhe Liu

1

, Hennie Daniels

2

and Wout Hofman

3

1

Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, Burg. Oudlaan 50, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

2

CentER, Tilburg University, Warandelaan 2, Tilburg, The Netherlands

3

Technical Sciences, TNO, Brasserplein 2, Delft, The Netherlands

Keywords: Explanatory Analysis, Interoperability, Decision Support, Risk Assessment.

Abstract: Systematic risk analysis can be based on causal analysis of business exceptions. In this paper we describe

the concepts of automatic analysis for the exceptional patterns which are hidden in a large set of business

data. These exceptions are interesting to be investigated further for their causes and explanations. The anal-

ysis process is driven by diagnostic drill-down operations following the equations of the information struc-

ture in which the data are organised. Using business intelligence, the analysis method can generate explana-

tions supported by the data.

1 INTRODUCTION

“Management by exceptions” has long been a

philosophy for business administration, in which

management can be described as a reflex arc of

monitor-control loop: the manager perceives the

environment of a company, forms an expectation,

and decides on the operations planning; additional

decisions will be made when deviations from the

expectation occur. Once an exception is detected, the

manager needs an explanation “why the exception

occurred”, so that he or she can make informed

decisions on subsequent (re-) actions – whether and

how to treat the exception.

In recent years, with the prevalance of Enterprise

Resource Planning (ERP) systems and the rising

awareness of the strategic value of business data,

companies continuously collect data about its

internal operations and external environment.

Business intelligence (BI) and analytics has been

vigorously applied in industry, translating data into a

competitive edge (Davenport, 2006). “Management

by exceptions” is then endowed with new

implication of “detecting and managing risks

proactively”, rather than the old ways of “reactive

fire-fighting” (Sodhi and Tang, 2009), with the new

terms of Risk Management or Risk Based Decision

Making. Exceptions are early risk indicators, albeit

not necessarily risky themselves. A company is

assumed to be homeostatic, that is, it can self-adapt

and operater normally unless the exception exceed a

threshold. At that point the exception turns into a

(materialized) risk. Risk management addresses the

vulnerability of the system – the condition in which

an exception will turn into a risk. In the analysis of

risk, it is important to understand the risk

propagation: how a seemingly small exception

causes a catastrophic system-wide failiure (see e.g.

Lund et al., 2011, Ch. 13). If such weak signal of

risk can be detected early in time, it leaves more

space for reaction and mitigation (Sodhi and Tang,

2009). Presumably, the pattern of risk propagation

must be implied in the historical events records of

business exception. Yet, to our best knowledge,

currently there is hardly any research on the general

methodology for analysing business exceptions

systematically.

In this paper we work towards a general

methodology on how to apply statistical methods

automatically to analyse the exceptional patterns

which are hidden in business data, based on (Caron,

2012). We also consider the method to establish a

clear view of the business events taking place in and

across companies. The paper is organized as follows.

In Section 2, we examine the concepts of BI

supported business analytics and discuss a general

model for the methodology. Section 3 discuss the

challenge of constructing data view from event logs,

especially that arises from integrating data which are

shared among companies in supply chain networks.

The practical aspects of the application are discussed

in Section 4, and the last section concludes the paper.

530

Liu L., Daniels H. and Hofman W..

Detecting and Explaining Business Exceptions for Risk Assessment.

DOI: 10.5220/0004569905300535

In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems (ICEIS-2013), pages 530-535

ISBN: 978-989-8565-59-4

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2 BUSINESS ANALYTICS

OF EXCEPTIONS

Modern management system, such as ERP, records

business data in large volume, but overloaded

information poses a problem for human decision

maker, as it confounds him/her from realizing the

true status of the system, causal relationship between

exceptions, and the effect of treatment measures

(Milliken, 1987). To avoid this, reports are

generated by aggregating the data before presented

to the manager. When the manager is examining the

report, he/she is looking for extreme or unexpected

items and try to find explanations using analytics,

i.e. reversing the process of report generation,

drilling down in a managerial model, or using

additional knowledge possibly from external

sources.

The use of analytics in business can be roughly

grouped into two parts. First, descriptive analytics

captures the pattern of systematic emergence in the

company or the environment. The description usual-

ly supports prediction. Examples are the data mining

algorithms like clustering, classification and associa-

tion, applied to identify the events which can possi-

bly lead to disasters. Although descriptive analytics

does not presume any expectations, the analyst usu-

ally looks for “interesting” patterns when interpret-

ing the results. In this process, implicit background

knowledge is applied in searching for (mental) ex-

ceptions (Keil, 2006).

Secondly, diagnostic analytics reason about the

causal relations of those patterns. The goal for this

type of the analysis is to restore or verify the mecha-

nism of a sequence of events (Keil, 2006), e.g. the

operations in the company. The conclusion usually

leads to decisions for adjustment and improvement

of the system. Exemplary analysis questions are

“why the company performance is not as expected”

– for improving performance of the managed sys-

tem, and “why certain exceptions have not been

detected by current monitors” – for adjusting the

management system. Audit analytics also falls in

this category, analysing the risk of fraud and/or

unintentional errors in accounting systems

(Vasarhelyi et al., 2004); (Bay et al., 2006). In the

framework we propose (see Section 2.2), we gener-

alize and combine these two types to the detection

and the diagnosis phases in an integrated process of

business analytics.

We argue that business analytics is a strategic

important process of organizational learning that

extends the philosophy of "management by excep-

tion". The importance of analytics lies in the neces-

sity of "meta-control" to cope with the internal and

external changes. The management system of the

company (ERP) monitors and controls the business

processes, which deliver value to customers and

form competitive competence. It automates the rou-

tine tasks of detecting and treating operational ex-

ceptions, because the business knowledge are codi-

fied into the build-in controls of the system (in form

of business rules or constraints) in a “plan-do-check-

adjust” cycle. With automation, management sys-

tems can help with handling these routine tasks in

large volume data (big data), e.g. managing thou-

sands of accounts in finance and cost accounting

systems. However, their monitor-control capability

is limited to the codified rules, so they cannot deal

with the “new” changes or the exceptions out-of-

scope of the rules. These exceptions are left to the

responsibility of human managers. Though the

“new” exceptions are on a higher system level than

the management system ergo not directly visible,

they affect the performance of the managed system

(the company): therefore, they must be detectable by

analysing the data collected / generated by current

management system. The analysis results in new

business knowledge that equips the management

system for controlling similar exceptions in the

future. Ideally, the managers hope to continuously

meta-control the management system, automating

the process using BI (Vasarhelyi et al., 2004).

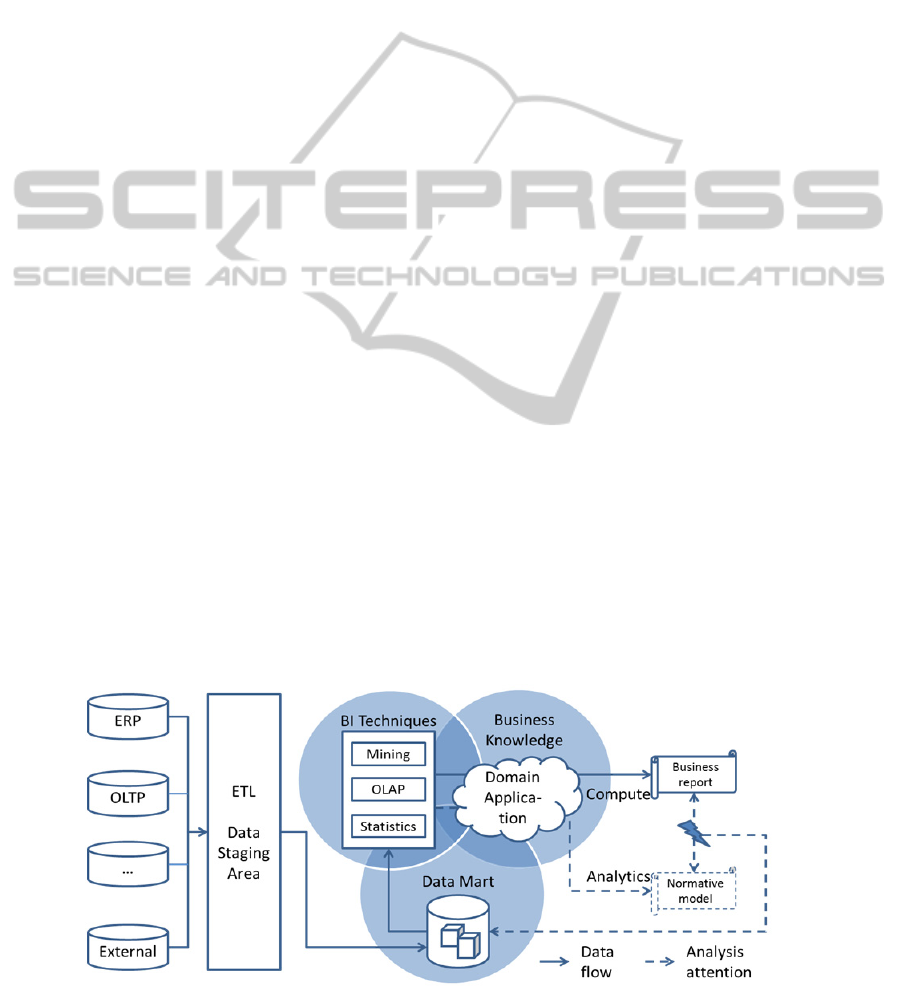

2.1 BI Supported Business Analytics

Business Intelligence is the collection of procedures

to reduce the volume of information that the manag-

er need to take into account when making decision.

The information-reduction is done by organising

(extract-transform-load, ETL) transactional data into

a multi-dimensional database (data warehouse or

OLAP), in which large volume of operational details

can be abstracted, aggregated or computed into

business reports, using BI techniques (see Figure 1).

This process involves both the managerial model

and the technical model of information organization.

On one hand, the organising of information is in

essence driven by managerial purpose, i.e. the man-

agerial model. For example, the accounting process,

which in general is a BI process, aggregates transac-

tion records in various documents such as journals,

general ledgers and financial statements for operat-

ing, financing and investing purposes respectively

(Bay et al., 2006). The organization of these docu-

ments codifies the managerial model. For instance,

the general ledger, recorded using double-entry

book-keeping, is a codified management system

DetectingandExplainingBusinessExceptionsforRiskAssessment

531

which internally controls balance between two ac-

counts involved in each transaction (Bay et al.,

2006).

On the other hand, the technical model organises

information for an analytical purpose. Organising

business data in the form of tables helps to highlight

contextual similarities among the data, providing

important support for the business analyst. For in-

stance, aligning records chronically, e.g. sales in

multiple periods, can show the temporal changes and

trends in the record set. As a special case, OLAP is a

useful tool to analyse multi-dimensional, hierar-

chical data interactively, with the standard drill-

down, roll-up and slice operations (Caron, 2012).

From an analytics viewpoint, the managerial model

provides an ontological structure of the information

(Hofman, 2013), while the technical model gives a

storage structure, also known as data structure in

computer science. Combining these two models

gives a data view of the business activities taking

place in the managed and the management systems.

We will come back to discuss the data view later in

Section 3.

2.2 A General Model for Business

Analytics

Before the analytic process can be automated, its

procedure should first be formalized. The lexical

definition of exception is “an instance that does not

conform to a rule or generalization” (thefreediction-

ary.com), which implies the comparison of the actu-

al instance to a norm. Our discussion on business

analytics is largely based on previous works of caus-

al analysis and explanations in (Caron and Daniels

2009); (Caron and Daniels, 2008); (Feelders and

Daniels, 2001); (Caron, 2012). The analysis of ex-

ceptions takes the canonical format of (Feelders and

Daniels, 2001):

〈

,,

〉

because

, despite

(1)

where

〈

,,

〉

is the triple for exception detection,

and the exception is to be explained by the non-

empty set of contributing causes

and the (possi-

bly empty) set of counteracting causes

. The di-

agnosis analysis is to explain why the instance

(e.g. the ABC-company) has property (e.g. having

a low profit) when the other members of reference

class (e.g. other companies in the same branch or

industry) do not.

The information structure of has the general

form of

, where

,

,⋯,

is an n-

component vector. In words, certain property value

of which is important for decision making, denot-

ed by, is dependent on other property values in

the information structure of.

We can use the information structure to estimate

the norm value of, given the actual values of.

Exception-detection is done by studying the differ-

ence between the actual and the norm value of.

|

,

(2)

where ~

0,

. If the difference is significant,

i.e.

|

|

,

is viewed as a symptom to be ex-

plained. The user defined threshold parameter

depends on the application domain, and the estima-

tion method for

|

depends on both

and

the application. A more general form of (2) is

|

info

(3)

where info stands for all kind of information availa-

ble. For example, Alles et al. (2010) uses the infor-

mation of sales of prior period

to estimate the

profit of current period

. The symptom is ex-

plained by the influence of each

, and the influ-

ence is measured as

inf

,

,

,,

(4)

Figure 1: Business analytics supported by BI.

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

532

where1,2,⋯,, and

,

denotes the

value of

with all variables evaluated at their

norm values, except

.

For clarity, we distinguish the technical model

from the managerial model in the information struc-

ture. For example in OLAP (see equation system

(5)), the variables in a managerial model (shown as

the functional relation) can be organised into a

hierarchy by aggregation, such as summation or

average (shown as the functional relation). Verti-

cally, all variables in the managerial model are or-

ganised based on the same aggregation relation.

Given that, the variables on a specific level of ag-

gregation follow the same business relation, just as

those variables on other aggregation levels horizon-

tally do.

In (5), the variables and are organized in an

OLAP cube with dimensions. Each dimension has

a hierarchy of

levels, where1,2,⋯. In a

specific dimension, variables on the hierarchy

level

are aggregated from the elements in the

lower hierarchy level

1, and these elements

are denoted respectively as

and

, where

1,2,⋯,. Here,

is an n-component vector,

whose components are denoted as

,

.

,

,⋯,

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

,

⋯

⋯

,⋯,

,

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

⋯

(5)

With the information structure available, we can

look at lower level of detail for explanation by drill-

ing down. For example, if there is a significant

symptom

in the OLAP model, detected

by

, we can drill down the

managerial model for explanations, using

. A necessary condition to obtain

sensible explanations by drilling down is consisten-

cy of the normative estimation, i.e.

y

|

(6)

This condition in relation with usually holds

for the OLAP model, but should be checked for

(statistical) managerial models in general. This issue

is studied in depth for ANOVA models in OLAP

databases (Caron, 2012).

3 ANALYTICS IN SUPPLY

CHAIN NETWORKS

The method for business analytics can be applied in

a company, a supply chain, or even supply chain

networks, since a supply chain system can also be

seen as “a big company”. This generalization is

relevant, as activities taking place in a company

influence, and can be influenced by those in other

companies in a supply chain. With this dependence,

the analytics of supply chain exceptions should in-

volve event logs shared by multiple companies.

In the supply chain context, risk analysis is per-

formed over the data which are shared during busi-

ness transactions between trading partners. Integrat-

ing these data to form a data view gives rise to the

challenges of interoperability (Hofman, 2013). Here

we limit the discussion to logistic services. Interop-

erability comprises three aspects that are closely

interrelated, namely 1) the logistic services resulting

in business transactions, 2) the semantics of shared

data, and 3) the choreography of business. The se-

mantics of data is a precondition for processing data

automatically. The choreography needs to be known

to derive the status (

) of physical processes and

business transactions which refer to logistic activi-

ties that are performed, e.g. transport of cargo con-

tainers. As such, these three aspects are part of the

managerial model relevant for monitoring supply

chain networks.

Under the assumption that companies share data

electronically, a data capture algorithm can crawl

these event logs regularly. And the data can be fused

to compose a supply chain view, organized in a

“business event store”. A condition is that all the

involved companies adhere to the same semantic

model. Transformations can be implemented in case

a company adheres to another semantic model than

agreed.

The business event store may contain duplicated

data for different business events, i.e. (almost) iden-

tical data can be stored for two or more business

events that are related to different companies. For

instance, two reports for a container may be stored,

referring to the delivery and the acceptance events of

the container. The data fusion component needs to

identify that these two reports are related, referring

DetectingandExplainingBusinessExceptionsforRiskAssessment

533

to the same business transaction involving the logis-

tics service provider and the cargo receiver.

The data fusion functionality has to mine the as-

sociation amongst the event logs by matching the

following properties of logistic service:

• Business transaction identifier: e.g. a Unique Con-

signment Number assigned to each complete chain

of transportation

• Sender/recipient: which construct the custom-

er/service provider relation for each transaction

• Place and time: each business event associates to a

place and time, e.g. place and time of acceptance

and of delivery

• Transaction hierarchy: this allows for decomposi-

tion of logistic activities, e.g. a journey of contain-

er transport may consist of several stretches of

transportation

4 PROCEDURE FOR ANALYTICS

Based on the discussion above, we can summarize a

general procedure for business analytics, with con-

sidering the practical methodology of data analysis

(Feelders and Daniels, 2000):

1. Define problem: define analysis goal and choose

the variable which is important for decision.

2. Establish context: abstract and explicitly specify

the information structure (or load from a

knowledge base, if available). The context is

usually connoted by the source of information

from which the business report was generated.

Sometimes external sources need to be included

to enlarge the context, depending on the analysis

goal.

3. Identify exceptions: choose appropriate reference

class, estimate the norm, and apply it to actual

data. Despite the wishes for fully automated

analysis, the derivation of the norm remains an

interactive process in which several practical as-

pects demand lots of background knowledge

from the analyst (see Section 4.1).

4. Generate explanations: relate the exceptions in

different parts of the business system and reason

about the causal relations, using equation (4).

Method for developing the relations has been

well studied in previous works (Caron and

Daniels, 2008); (Caron and Daniels, 2009), in-

cluding greedy and top-down explanation.

5. Interpret results: review the explanations. In case

the results does not sufficiently supports deci-

sion, repeat step 2 to 5.

4.1 Practical Aspects

The following two key tasks are the most intricate in

the process of business analysis:

1. How to find an appropriate normative model to

detect exceptions, and

2. How to find the real causes to explain the rela-

tionship between the exceptions.

4.1.1 Exploration: Finding an Appropriate

Norm

Business analysis is in any case an exploratory pro-

cess. The normative model plays a central role in

qualifying a feature as normal or exceptional. The

firstly used normative models to detect symptoms

are usually the codified business constraints in the

management system, such as plans or budgets. Pecu-

liarly, in the subsequent diagnostic analysis to ex-

plore a sensible explanation, the choice of the nor-

mative model for the lower level of analysis relies to

a large extent on the choice of the analysis context,

because the analysis goal is usually an open ques-

tion. For instance, a decrease in profit may due to

the drop in internal efficiency or the deteriorated

global economy.

In the exploration for the subsequent normative

models, statistics are usually applied to the analysis

context, i.e. the members of the reference class.

With a data driven (bottom-up) approach, the meth-

od for choosing a proper reference class can be “sof-

tening” the set of business constraints used in the

management system for a particular monitor, using

an un-slice operation.

Softening business constraint is a useful tech-

nique for analysis. The un-slice operation takes the

union of the data sets which correspond to different

parts of the system. It thus expands the analysis

scope, so that the patterns on a larger system scale

can be revealed. For example, in the time dimension,

the trend or fluctuation of a variable over time can

only be seen on a time period, but not at a time

point. Besides, expanding the scope by un-slicing is

in itself an attempt of exploration, for instance in

searching for those exceptions whose impact only

takes effect after a time lag (Alles et al., 2010). This

in general helps the analyst to involve extra data by

extending the current information structure: in any

case, one can always organize the information of the

analysis context into an OLAP-like structure, and

then start to expand.

The reference class is always defined by a set of

constraints. Reminding of the codified business

constraints in the first place, the exploration for an

ICEIS2013-15thInternationalConferenceonEnterpriseInformationSystems

534

appropriate reference class can be regards as a “me-

ta-control” process that diagnoses and reflects upon

the detective power of the current set of constraints,

performed by the analyst (see Section 2). The explo-

ration thus iteratively applies the detective and diag-

nostic processes on the design of the business analy-

sis method.

4.1.2 Validation: Finding the Real Cause

Correctness and relevance are two important criteria

for evaluating the explanation. The correctness of

the models in the information structure is a premise

for finding the real cause. If the model doesn’t cap-

ture the business correctly, the reference model

would be based on a false assumption, and it would

then be incapable even in explaining a normal effect.

As a result, the model will possibly raise many false

alarms.

The relevance concerns the usefulness of the ex-

planation for decision support. A counter-example is

the explanation presented at the wrong level of detail

(also pointed out in Keil, 2006). The method for the

evaluation of the correctness and relevance generally

rely on the background knowledge of the application

domain.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Current business databases contain massive amounts

of data that carry important explicit and implicit

information about the underlying business process.

In this paper we have shown how general statistical

methods can be applied to automatically detect im-

plicit patterns that are interesting to be investigated

further for risk assessment. In many cases the data

itself include enough information to discover unusu-

al patterns or trends to be explored further, like in an

OLAP database. The process of examination is driv-

en by accounting equations or drill-down equations

and can generate explanations supported by the data.

In the future we want to investigate the incorpora-

tion of heterogeneous external data sources to obtain

a richer structure for causal analysis as described in

this paper. A case study in risk management in

global supply chains is currently explored.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the EC FP7 project

CASSANDRA (Grant agreement no: 261795).

REFERENCES

Alles, M. G.., Kogan, A., Vasarhelyi, M. A. & Wu, J.

2010. Analytical Procedures for Continuous Data

Level Auditing: Continuity Equations. Available at:

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.

1.1.174.240 [Accessed February 3, 2013].

Bay, S., Kumaraswamy, K., Anderle, M. G., Kumar, R. &

Steier., D. M. 2006. Large scale detection of

irregularities in accounting data in Data Mining, 2006.

ICDM’06. Sixth International Conference on. IEEE,

pp. 75–86.

Caron, E. A. M. & Daniels, H. A. M. 2009. Business

Analysis in the OLAP Context in J. Cordeiro et al.

eds., ICEIS 2009. Milan, Italy, pp. 325–330.

Caron, E. A. M. 2012. Explanation of Exceptional Values

in Multi-dimensional Business Databases. Erasmus

University Rotterdam. Available at: http://www.

emielcaron.nl/papers/Thesis.pdf.

Caron, E. A. M. & Daniels, H. A. M. 2008. Explanation of

exceptional values in multi-dimensional business

databases. European Journal of Operational Research,

188(3), pp.884–897.

Davenport, T. 2006. Competing on analytics. harvard

business review, 84(1), pp.98–107.

Feelders, A. & Daniels, H. A. M. 2001. A general model

for automated business diagnosis. European Journal

of Operational Research, 130(3), pp.623–637.

Feelders, A. & Daniels, H. A. M. 2000. Methodological

and practical aspects of data mining. Information &

Management, 37(5), pp.271–281.

Hofman, W. 2013. Compliance management by business

event mining in supply chain networks in VMBO.

Delft, the Netherlands.

Keil, F. C. 2006. Explanation and understanding. Annual

review of psychology, 57, pp.227–54.

Lund, M.S., Solhaug, B. & Stølen, K. 2011. Model-driven

risk analysis: the CORAS approach. Springer-Verlag

Berlin Heidelberg.

Milliken, F. J. 1987. Three Types of Perceived

Uncertainty about the Environment: State, Effect, and

Response Uncertainty. The Academy of Management

Review, 12(1), p.133.

Sodhi, M. S. & Tang, C. S. 2009. Managing Supply Chain

Disruptions via Time-Based Risk Management in T.

Wu et al. eds., Managing Supply Chain Risk and

Vulnerability. London: Springer, pp. 29–40.

Vasarhelyi, M. A., Alles, M. G. & Kogan, A. 2004.

Principles of analytic monitoring for continuous

assurance. Journal of Emerging Technologies in

Accounting, 1(1), pp.1–21.

DetectingandExplainingBusinessExceptionsforRiskAssessment

535