An Analysis of Multi-disciplinary & Inter-agency Collaboration

Process

Case Study of a Japanese Community Care Access Center

Miki Saijo

1

, Tsutomu Suzuki

2

, Makiko Watanabe

3

and Shishin Kawamoto

4

1

International Sudent Center, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Tokyo, Japan

2

Faculty of Liberal Arts, Tohoku Gakuin University, Sendai, Japan

3

Graduate School of Science and Technology, Tokyo University of Science, Chiba, Japan

4

Institute for the Advancement of Higher Education, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan

Keywords: Community Care Access Center, Multi-disciplinary and Inter-agency Collaboration, Elderly Care, KJ

Method.

Abstract: This study examines the process of collaboration between multi-disciplinary agencies at a Community Care

Access Center (CCAC) for elderly care. Using the KJ method, also known as an “affinity diagram”, in two

group meetings (before and after CCAC establishment) with practitioners and administrators from 6

agencies in the city of Kakegawa, Japan, 521 comments by agencies (214 from a meeting in 2010 and 307

from a meeting in 2012) were coded into 36 categories. In comparing the comments from the two meetings,

the portion of negative comments regarding organization management decreased, while comments on the

shared problems of the CCAC, such as difficult cases, user support, effectiveness, and information sharing

increased. A multiple correspondence analysis indicated that the 6 agencies shared a greater awareness of

issues after the establishment of the CCAC, but the problems pointed out by the agency with nurses

providing in-home medical care differed from those of the other agencies. From this, it has become apparent

that group meetings and comments analysis before and after launching a CCAC could illustrate the process

of multi-disciplinary and inter-agency collaboration.

1 INTRODUCTION

The aging society is a society in which elderly

people account for a large proportion of the

population. This is a trend we are seeing around the

world, but in Japan it is happening more rapidly and

in significantly larger numbers than elsewhere. By

2025, Japan will have 36 million people aged 65 and

older. This means that the elderly will account for

30% of the total population. We need an effective

health care system for this large cohort of aging

population within the demographic onus structure.

In order to cope with this tendency, the Japanese

government changed the system for elderly care

from institutional health care to community care.

This community care provides the elderly with in-

home nursing and medical care through a

community general support center (CGSC) system

launched in 2008 (Ministry of Health, Labour and

Welfare, 2011). However, Japan’s CGSCs do not

provide the kind of coordinated nursing and medical

care that is provided by such agencies as the

Community Care Access Centers (CCACs) of

Ontario, Canada (OACCAC, 2009). A CCAC

requires multi-disciplinary and inter-agency

collaboration among medical, nursing-care, and

welfare practitioners, but for practitioners in

different fields to work together effectively, trust is

necessary, and this relationship of trust needs to be

established at an early stage (Bromiley and

Cummings, 1995); (McKnight et al., 1998). There is

little research, however, that is based on the analysis

of real-world examples of individuals in different

professions and organizations cooperating with each

other (Okamoto, 2001); (Salmon, 2004); (Paletz,

2013).

This study elucidates the process of multi-

disciplinary and inter-agency collaboration by

making a case study of Fukushia, a Japanese-style

CCAC health care system in Kakegawa, Shizuoka

prefecture, and analyzing the comments shared in

470

Saijo M., Suzuki T., Watanabe M. and Kawamoto S..

An Analysis of Multi-disciplinary & Inter-agency Collaboration Process - Case Study of a Japanese Community Care Access Center.

DOI: 10.5220/0004624604700475

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Information Retrieval and the International Conference on Knowledge

Management and Information Sharing (KMIS-2013), pages 470-475

ISBN: 978-989-8565-75-4

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

group meetings of the participants held just before

and after (2010, 2012) the launching of the CCAC.

2 LITEATURE REVIEW

2.1 Inter-agency Collaboration

In the UK, there has been an awareness since the

1970s of the need for multi-disciplinary and inter-

agency collaboration in child and adolescent mental

health services (DoH, 1997), and many studies have

been made of the topic (Okamoto, 2001); (Salmon,

2004); (Robinson and Cottrell, 2005); (Salmon and

Faris, 2006). These studies focus on how

practitioners from several different agencies

cooperate in the area of public health for youth, but

many of their conclusions can be equally applied to

the topic of general community care for the elderly.

Okamoto, 2001, for example, examines how

individuals with different professions in different

organizations work together to address the issue of

mental health among gangs of young people who are

at high risk of becoming criminals.

The elements of successful multi-disciplinary

and inter-agency collaboration are communication

and cooperation (Okamoto, 2001); (Salmon, 2004);

(Robinson and Cottrell, 2005); (Salmon and Faris,

2006). McKnight et al., 1998, emphasizes the role of

communication in forging initial relationships of

trust among inter-agency and cross-functional team

members, and makes the following propositions: in

initial relationships, highly trusting intentions are

likely to be robust when (1) the parties interact face

to face, frequently and in positive ways, or (2) the

trusted party has a widely known good reputation.

Still, these studies do not examine the methodology

for achieving good communication among

prospective collaborators nor explain how their

mutual reputations are forged.

2.2 Common Frame of Reference

(COFOR)

In a multi-disciplinary and inter-agency team, each

member perceives the goals and problems

differently depending on their knowledge and

interests. This is precisely why it is important that all

participants are aware of their respective perceptions,

convictions and motivations (Marmolin and

Sundblad, 1991). Individuals with different fields of

specialty, however, will each interpret what they see

differently even when they are looking at the same

thing. It is necessary, therefore, that they share a

common frame of reference for interpreting and

integrating the information they communicate

among themselves (Marmolin and Sundblad, 1991);

(Hoc and Carlier, 2002). This common frame of

reference (COFOR) is a mental structure that plays a

functional role in cooperation. COFOR is only

accessible to the observer by means of external

entities, such as input and output (communication

between agencies), or external representations in

common media (e.g., a duty roster) (Hoc and Carlier,

2002).

2.3 KJ Method

A common frame of reference is an informal mental

structure, albeit with a societal aspect, that

participants need to build together. At the same time,

this kind of informal structure can be difficult to

recognize and is hard to make transparent. One

solution to the problem of achieving COFOR

transparency within the context of a multi-

disciplinary and inter-agency CCAC is the

application of the KJ method in group meetings and

the creation of diagrams and charts showing the

output from those meetings.

Devised by a Japanese anthropologist named

Kawakita Jiro, the KJ method is a generalized brain

storming technique—what he called an “idea-

generating” methodology—to gather qualitative data

(Scupin, 1997). The KJ method has been widely

adopted in business circles, not so much for

generating new ideas, but for its effectiveness in

consensus making (Takeda et al., 1993). The KJ

method is a theory generating methodology like the

grounded theory methodology of Strauss and Corbin,

1990. In group discussions using the KJ method,

individuals write their opinions as short phrases on

slips of sticky notes or labels. There are four

essential steps in the process: 1) label making, 2)

label grouping, 3) chart-making, and 4) written or

verbal explanation (Scupin, 1997). Everyone in the

group participates in the step 1 process of label-

making. After that, trained facilitators carry out steps

2 through 4, intuitively sorting the labels into groups

and creating a diagram linking the groups with lines

(A chart). This diagram, the so-called A chart, will

help to show the connections and open the way for

new interpretations, and this is the distinguishing

feature of the KJ method (Kawakita et al., 2003).

Participants in a CCAC who are trying to achieve

multi-disciplinary collaboration could apply the KJ

method to create a COFOR for solving the issues

that confront them. A comparison of the diagrams

created before and after the launching of the CCAC

will show how their perceptions of the issues have

AnAnalysisofMulti-disciplinary&Inter-agencyCollaborationProcess-CaseStudyofaJapaneseCommunityCare

AccessCenter

471

changed and should help in clarifying the

collaboration process. In the KJ method, a trained

facilitator creates an A chart giving an overview of

the issues, grouping the problems on the basis of

experience and intuition. This, of course, means that

the diagram will be slanted by the facilitator’s

personal perceptions and assumptions. For the

purposes of this study, the labels generated in the

group meetings were sorted according to the

similarity of the issues they addressed. We did not

attempt to examine the effectiveness of the group

meetings in achieving COFOR, but instead used the

labels as output of the group meetings to define the

process of CCAC collaboration.

3 CASE STUDY METHODOLOGY

3.1 Background

Multi-disciplinary and inter-agency collaboration is

essential for community-based care of the elderly.

Take, for example, the case of an old man who is

released from a hospital after suffering a mild stroke.

He is unable to walk and shows dementia-like

symptoms, but everyone in the family works, and

during the day the old man is left at home alone.

Even in a large city like Tokyo, there is no facility

where an individual like this can be immediately

admitted, and in any case the cost is much too high

for the family. If this man is to get in-home care so

that he will not become totally bedridden, he needs

the coordinated support of the following: A hospital

community coordinator who can decide what kind of

support and guidance the man will need after being

discharged; a senior nursing care manager who can

make arrangements for the home renovations that

will be needed for in-home care; the public health

care nurses and visiting nurses assigned to the area

where the old man lives

Japanese local administrations are often

criticized for being overly compartmentalized, but

for effective community-based care of the elderly,

this kind of tendency needs to be overcome. On the

premise that multi-disciplinary and inter-agency

case-level collaboration is best achieved when all

parties concerned are housed in the same building,

the city of Kakegawa launched a new Japanese-style

CCAC called Fukushia in 2011 with plans to build a

total of five such facilities throughout the city by

2015. Each Fukushia is staffed by personnel from

six different agencies including city hall, the local

social welfare council, the community general

support center (CGSC), a visiting nurses’ station, the

Kakegawa senior care manager liaison association,

and the local city hospital, who cooperate in

providing social welfare services.

In 2010, prior to the launching of the new facility,

the authors were asked by Kakegawa city to

interview the staff of all six agencies. All of the staff

interviewed expressed misgivings of the

organizational management of Fukushia, including

their own agency management: they worried about

how they could work effectively with their

counterparts in such different organizations. It was

evident that collaboration would be difficult even

with a new organizational structure and facility. It

was therefore decided to hold group meetings in

which the KJ method would be applied. This paper

examines the results of two group meetings sharing

the same protocol that were held before (2010) and

after (2012) the Fukushia launching.

3.2 Method

Our research question was, “What is the process of

multi-disciplinary and inter-agency collaboration

between administration staff and practitioners within

a highly differentiated and complex system of care

for the elderly?” Our approach to finding an answer

was to carry out a quantitative analysis of the KJ

method label output from the two group meetings.

The labels bore comments made by the staff of the

six agencies about each other.

In our analysis, we looked first to see what kinds

of comments increased or decreased in relation to

the awareness of problems. This was done by

comparing the number of comments made at the two

meetings before and after the launching CCAC, and

recording the difference. Our next objective was to

see if there was any change in the affinity of

awareness of problems among the meeting

participants in the two meetings, and this was done

through multiple correspondence analysis of the

comments made at the two meetings.

The two meetings were attended each time by 29

practitioners and administrative staff from the six

agencies comprising Fukushia. The first meeting

participants were: 8 from city hall; 10 from the

CGSC; 3 from the local social welfare council; 3

from the visiting nurses station; 2 from the local

hospital, and 3 care managers. For the second

meeting: 10 from city hall; 8 from the CGSC; 4 from

the local social welfare council; 2 from the visiting

nurses station; 4 from the local hospital, and 1 care

manager. At each meeting, the 29 participants were

divided into 6 groups and given sticky labels on

which to write their comments; blue labels for

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

472

comments about their own agency and red labels for

comments about the other agencies. On the red

labels, participants were asked to write their own

agency name and the name of the agency they were

commenting about. The meetings were chaired by

the lead author of this paper. The red and blue labels

where pasted onto a white board so that everyone

could see what kind of comments were being made

and which agencies were making the comments. The

first meeting produced 220 comments and the

second, 314 for a total of 534 comments. After

excluding 13 illegible comments, 521 comments

were then coded into 36 categories according to the

issue or problem they referred to. This task was

carried out individually by three researchers, and

where the results did not correspond, a final decision

was made through discussion among the three.

Finally, the comments were sorted in a cross-

tabulation table for multiple correspondence analysis.

4 FINDINGS

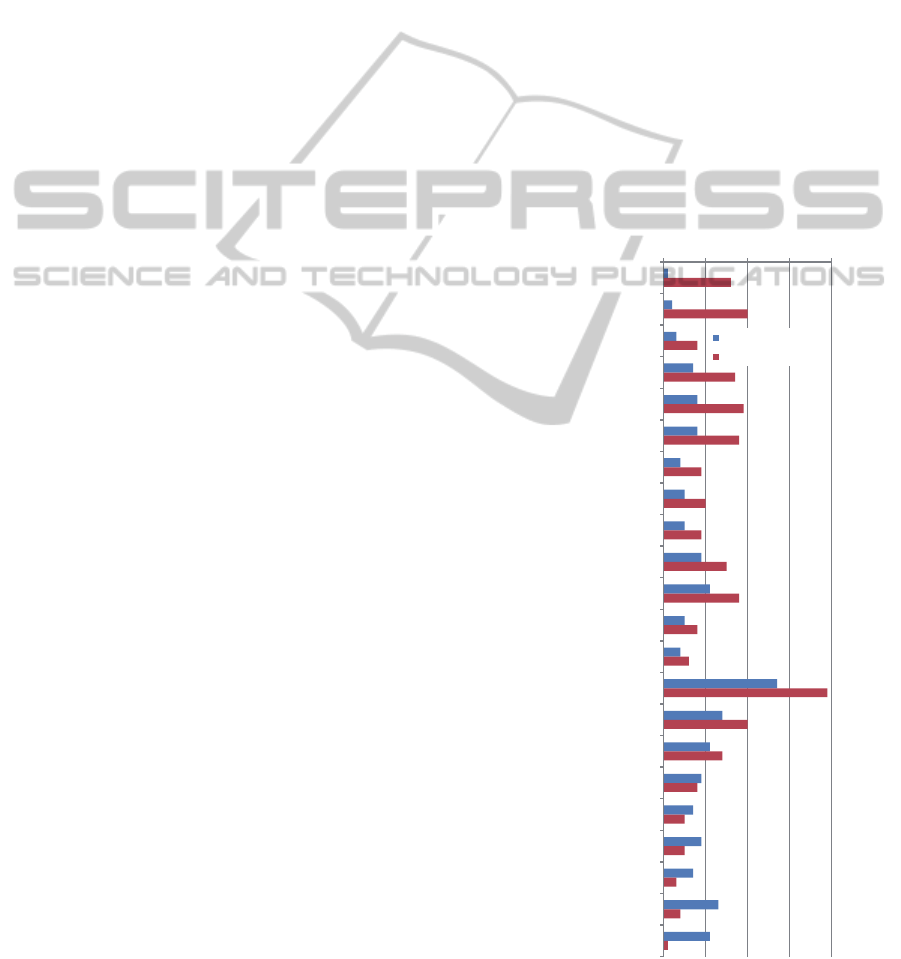

4.1 Changes in Comment Proportions

For a better grasp of the trends, a comparison if the

change in number of comments between the first and

second meetings was made in categories that had 10

or more comments in total from the two meetings.

Figure 1 shows the change in proportion between the

comments from the first and second meetings,

starting with those showing the greatest increase in

the second meeting at the top of the chart. The

comments that showed the greatest increase in the

second meeting were those related to specific shared

issues of the CCAC. These comments were

classified into the categories of “difficult cases”,

“user support”, “regional collaboration”, “in-home

care”, and “patients”. There was also a notable

increase in the number of comments related to work

procedures, in the categories of “effectiveness”,

“information sharing”, and “complicated

procedures”.

There was little change in the number of

comments made at the two meetings in the

categories of “inconsistency”, “lack of doctors”,

“insufficient human resources”, those related to

problems of organization structure and procedures.

Likewise, little change was seen in the number of

comments related to inter-agency and intra-agency

collaboration. To be more precise, there was an

increase in the actual number of comments, but little

change in the proportionate share of these comments

within the designated categories. A decrease was

evident in the number of comments related to the

organization as such. These were comments on

“agency management”, “compartmentalization”,

“developing human resources” and “insufficient

publicity”.

In the second meeting only, participants came up

with a total of 76 positive comments which included

the following: Comments on cooperation, from the

social welfare council to city hall: appreciation for

taking over when council staffs were absent; from

the CGSC to the care managers liaison association:

appreciation for reporting back on follow-up.

These results indicate that while the six agencies

had many critical comments related to the

organization management at the time of the

launching of Fukushia, after the facility was set up

their comments focused more on such factors as the

quality of general community care services and

specific shared issues of concern, rather than on

criticisms of organizational structure or attitudes.

1

2

3

7

8

8

4

5

5

9

11

5

4

27

14

11

9

7

9

7

13

11

16

20

8

17

19

18

9

10

9

15

18

8

6

39

20

14

8

5

5

3

4

1

010203040

Difficult cases

User support

Effectiveness

Information sharing

Complicated procedures

Regional collaboration

In-home care

Patients

Staff absence

Requests for services

Over-worked

Inconsistency

Lack of doctors

Inter-agency collaboration

Intra-agency collaboration

Insufficient human resources

Integrated care system

Abilities

Insufficient publicity

Developing human resources

Compartmentalization

Agency management

1st meeting (N=214)

2nd meeting (N=307)

Figure 1: Proportion of comments from the two group

meetings.

AnAnalysisofMulti-disciplinary&Inter-agencyCollaborationProcess-CaseStudyofaJapaneseCommunityCare

AccessCenter

473

−4 −3 −2 −1 0 1 2

−4 −3 −2 −1 0 1 2

axis1 19.95 %

axis2 18.5 %

Care manager association1

City hall 1

Social Welfare Council 1

Hospital 1

CGSC 1

Home−visit nursing agency 1

Care manager association2

City hall 2

Social Welfare Council 2

Hospital 2

CGSC 2

Home−visit nursing agency 2

Insufficient publicity

Taking on too much

Speed

Motivation

Staff changes

Lack of doctors

Work imposition

Care prevention

Patients

Requests for services

Transport

Difficult cases

In−home care

Narrow views

Compartmentalization

Information sharing

Insufficient human resources

Developing human resources

Integrated care system

Diffusion of responsibility

Insufficient explanation

Specialization

Agency management

Inter−agency collaboration

Intra−agency collaboration

Over−worked

Discharge support

Regional differences

Regional collaboration

Abilities

Staff absence

Inconsistency

Burden imbalance

Complicated procedures

Effectiveness

User awareness

User support

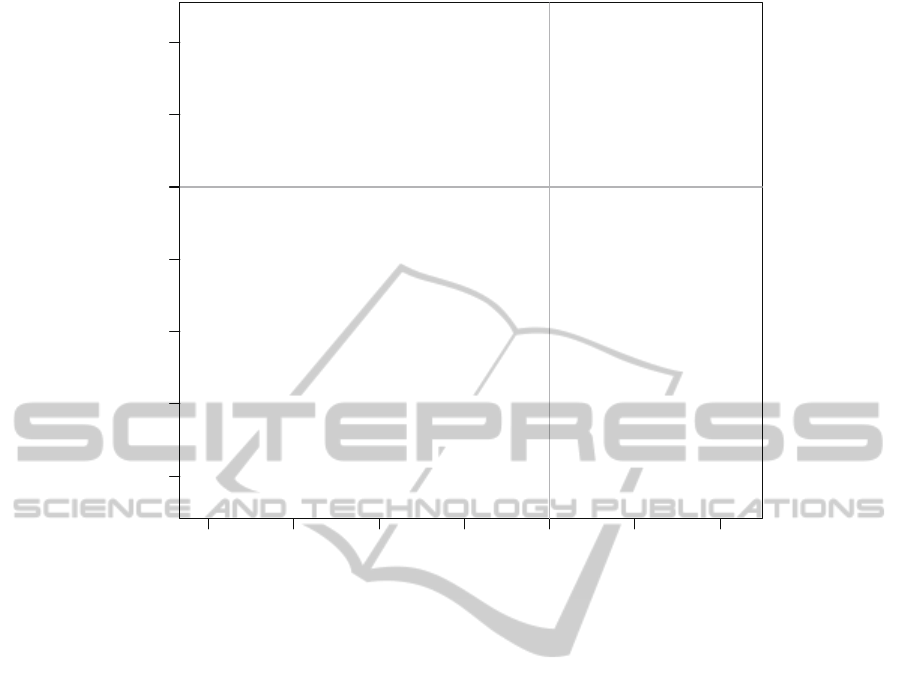

Figure 2: Multiple correspondence analysis of comments from the two group meetings; Phrases in black indicate agencies.

The numbers 1 and 2 indicate the first or second meeting, and the phrases in red indicate categories.

4.2 Changes in Awareness Affinity

among the Six Agencies

Figure 2 shows the result of multiple correspondence

analysis of the comments from the first and second

group meetings. This analysis shows that by the

second meeting all but the visiting nurses station had

come to share a similar awareness of the problems.

In the first group meeting, the six agencies shared

similar concerns about agency management,

“information sharing” and “intra-agency

communication”, but by the second meeting their

shared concerns had expanded to encompass specific

problems of health care, such as “regional

collaboration”, “lack of doctors” and “discharge

support”.

The meeting participants from the visiting nurses

station only raised issues within their own

organization and made absolutely no comments

about the other agencies. The issues they raised

included such topics as—“With only 3 fulltime staff,

there is considerable after-hours burden”, “it is

difficult to establish an effective visiting program

plan”, “there are citizens and care managers who are

unaware of the visiting nursing program” and

“financial difficulties in management”—all issues

that are difficult for the visiting nurses agency to

solve on its own. The fact that the visiting nurses

agency is the only private business participating in

Fukushia is probably a contributing factor to the

problems the visiting nurses appear to have in

communicating with the other agencies, but it should

also be noted that the issues raised by nurses tend to

be introverted. The services provided by the visiting

nurses are crucial to Fukushia and there is a critical

need to address the issue of how the other agencies

may provide better support to the visiting nurses

station.

5 DISCUSSION

The analysis of the comments made at the two group

meetings held before and after the launching of

Fukushia show that there was a change from

criticism of organizational management to a shared

focus on specific issues confronting Fukushia as a

CCAC. It is evident that the six agencies had come

closer to a common awareness of the issues before

KMIS2013-InternationalConferenceonKnowledgeManagementandInformationSharing

474

them. Clearly, the six agencies had overcome their

mutual fear to forge a stronger awareness of their

shared role as a public provider of general

community care services. At the same time, however,

it was evident that the private visiting nurses station

did not share this general awareness.

Only two or three individuals from the visiting

nurses station attended the group meetings and they

can hardly be said to be representative of their

organization. If general community care is to evolve

from a mere concept to a truly multi-disciplinary and

inter-agency undertaking to provide specific

community services, and if it is to include private

enterprise, strategies will be needed to tackle the

issues that have arisen since the launching of

Fukushia, issues which are represented by the

keywords of “regional collaboration”, “lack of

doctors” and “discharge support”. The next step is to

decide what kind of communication among the six

agencies is needed to achieve this.

In this study, we also proposed a method to clarify

the COFOR in problem awareness among the

Fukusia members. It was found that a degree of

objectivity could be achieved by applying multiple

correspondence analysis to the awareness affinity

diagram created by the meeting facilitators based on

their subjective observations in previous studies.

This led us to the conclusion that it may be possible

to objectively externalize the latent potential for a

multi-disciplinary and inter-agency collaboration

COFOR, using the group meetings and the analysis

of the comments. However, we were not able to

analyze the impact of the group meetings or the

affinity diagram on the awareness of the individual

participants in the meetings. We have therefore been

unable to examine the factors that may have

contributed to the change in the Fukushia members’

awareness. Still, there was discussion among all

participants, after the group meetings using the KJ

method labels, on what changes had or had not taken

place in the year since the launching of Fukushia.

We hope later to apply the theoretical COFOR

framework of Hoc, 2001, to this discussion to

analyze its aspects of cooperative activities.

REFERENCES

Bromiley, P., & Cummings, L. L., 1995. Transactions

costs in organizations with trust. Research on

negotiation in organizations, 5, 219-250.

Department of Health, 1997. NHS planning and priorities

guidance 1997/98. London: HMSO.

Hoc, J. M., 2001. Towards a cognitive approach to

human–machine cooperation in dynamic situations.

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies,

54(4), 509-540.

Hoc, J. M., & Carlier, X., 2002. Role of a common frame

of reference in cognitive cooperation: sharing tasks

between agents in air traffic control. Cognition,

Technology & Work, 4(1), 37-47.

Kawakita, J., Matsuzawa, T., Yamada, Y., 2003.

Emergence and Essence of the KJ Method: An

Interview with Jiro Kawakita. Japanese Journal of

Qualitative Psychology, 2003, 2(2), 6-28.

Marmolin, H., Sundblad, Y., & Pehrson, B., 1991. An

analysis of design and collaboration in a distributed

environment. In Proceedings of the second conference

on European Conference on Computer-Supported

Cooperative Work, 147-162. Kluwer Academic

Publishers.

McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L.,

1998. Initial trust formation in new organizational

relationships. Academy of Management review, 23(3),

473-490.

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2011. Act for

Partial Revision of the Long-Term Care Insurance Act,

Etc., in Order to Strengthen Long-Term Care Service

Infrastructure; 2011. Available at: http://www.mhlw.

go.jp/english/policy/care-welfare/care-welfare-elderly/

dl/en_tp01.pdf.

Okamoto, S. K., 2001. Interagency collaboration with high

risk gang youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work

Journal, 18(1), 5–19.

Ontario Association of Community Care Access Centres,

2009. 2009/2010 CCAC QUALITY REPORT.

Available at: http://www.ccac-ont.ca/uploads/201106-

CCAC_Quality_Report/CCAC_Quality_Report_EN/i

ndex.htm.

Paletz, S. B., Schunn, C. D., & Kim, K. H., 2013. The

interplay of conflict and analogy in multidisciplinary

teams. Cognition, 126(1), 1-19.

Robinson, M., & Cottrell, D., 2005. Health professionals

in multi-disciplinary and multi-agency teams:

changing professional practice. Journal of

Interprofessional care, 19(6), 547-560.

Salmon, G., 2004. Multi-agency collaboration: the

challenges for CAMHS. Child and Adolescent Mental

Health, 9(4), 156–161.

Salmon, G., & Faris, J., 2006. Multi-agency collaboration,

multiple levels of meaning: social constructionism and

the CMM model as tools to further our understanding.

Journal of family therapy, 28(3), 272-292.

Scupin, R., 1997. The KJ method: A technique for

analyzing data derived from Japanese ethnology.

Human organization, 56(2), 233-237.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. 1990. Basics of qualitative

research, 15. Newbury Park, CA: Sage publications.

Takeda, N., Shiomi, A., Kawai, K., & Ohiwa, H., 1993.

Requirement analysis by the KJ editor. Requirements

Engineering, 1993. Proceedings of IEEE International

Symposium on, 98-101.

AnAnalysisofMulti-disciplinary&Inter-agencyCollaborationProcess-CaseStudyofaJapaneseCommunityCare

AccessCenter

475