Effect of Stimulus Size and Shape on Steady-State Visually Evoked

Potentials for Brain-Computer Interface Optimization

Wenjie Zheng, François-Benoît Vialatte, Parvaneh Adibpour, Chen Chen,

Antoine Gaume and Gérard Dreyfus

SIGnal Processing and MAchine Learning (SIGMA) laboratory, École Supérieure de Physique et de Chimie

Industrielles de la ville de Paris (ESPCI ParisTech),75005 Paris, France

Keyword: SSVEP, Stimulus, Size, Shape, Checkerboards, BCI.

Abstract: Steady-state visually evoked potentials (SSVEP) can be elicited by a large variety of stimuli. To the best of

our knowledge, the size and shape effect of stimuli has never been investigated in the literature. We study

the relationship between the visual parameters (size and shape) of the stimulation and the resulting brain

response. A tentative physiological interpretation is proposed and the potential of the effect in a Brain-

Computer Interface is outlined.

1 INTRODUCTION

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) allows a direct

communication of an individual to a computer

through direct measurements of brain electrical

activity (Nicolelis et al., 2000). Since Hans Berger

recorded the first electroencephalogram (EEG) from

the human scalp and discovered the brain alpha

waves (neural oscillations in frequency range of 8-

12 Hz, Berger 1929), EEG has become a major

noninvasive technique for studying brain activity. It

is believed that EEG is mostly reflecting the

synaptic activity that occurs in the superficial layers

of the cortex.

Sensory evoked potentials are electrical

responses of the brain (usually EEG) elicited by

sensory stimulation. They can be recorded from the

central nervous system of humans or animals while

visual, somatosensory, or auditory modalities are

stimulated (Dawson, 1954) ; they are distinct from

spontaneous potentials (background EEG), that can

be recorded without stimulation (Vialatte et al.,

2010). Steady-state visual evoked potentials (SSVEP)

are signals that are responses to a visual stimulation

at a constant frequency. The Fourier spectrum of the

EEG signal exhibits characteristic SSVEP peaks that

are stable over time. SSVEP signals have a better

signal-to-noise ratio than other visual evoked

potentials, so that they are good candidates for

applications in brain-computer interface systems

(Vialatte et al., 2010). SSVEP are measured in the

human visual cortex when the retina is exposed to a

flickering visual stimulus that, in our experiments, is

a computer-generated image that flickers at constant

frequency. EEG electrodes located above the

occipital lobe (where the visual cortex is located)

record the brain response.

The limits and properties of SSVEP are not

completely known. A better understanding of these

properties would allow better designs for SSVEP-

based BCI systems. In a previous investigation, we

had for instance challenged the lower limits of

SSVEP (Vialatte et al., 2008). In the present

manuscript, we investigate the effect of the visual

stimulus size and shape on the fundamental and

higher harmonics of the SSVEP response. In

addition, we investigate the possibility of using

visual stimuli with that elicit common harmonics as

SSVEP commands.

2 METHOD

2.1 Subjects

We recorded EEG signals from 13 young adults

(ages 20-26, 11 males and 2 females). All subjects

were healthy with normal or corrected-to-normal

vision. They had no history of brain disorder or

anomaly.

574

Zheng W., Vialatte F., Adibpour P., Chen C., Gaume A. and Dreyfus G..

Effect of Stimulus Size and Shape on Steady-State Visually Evoked Potentials for Brain-Computer Interface Optimization.

DOI: 10.5220/0004667705740577

In Proceedings of the 5th International Joint Conference on Computational Intelligence (SSCN-2013), pages 574-577

ISBN: 978-989-8565-77-8

Copyright

c

2013 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

2.2 Stimulus Design

The source of the stimulus was a Samsung

S23A750D LED screen with 120Hz input and

display refresh rate, with 250 cd/m² luminous

intensity. Subjects were placed at ~1 m from the

screen, sitting in a relaxed position. During the

experiments, a succession of flickering images is

presented to the subjects. Five different stimulus

sizes and five different stimulus shapes were tested.

This display was realised using Cogent Graphics

developed by John Romaya at the LON at the

Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience,

and using Hovagim Bakardjian’s BCI-SSVEP-LCD

toolbox.

2.3 EEG Recording

EEG was recorded using an Acticap system with 16

active channels connected to a V-Amp amplifier

from Brain Products. Signals were filtered with a

band-pass filter (0.5-100 Hz) and a notch filter at 50

Hz, and sampled at 500 Hz. The EEG signals were

recorded from 4 channels located above the visual

cortex (PO

3

, PO

4

, O

1

, and O2 in the 10-20

international system).

2.4 Effect of Stimulus Size

We used a flickering black and white rectangle as

visual stimulus to test the effect of size on SSVEP

responses. Responses to stimuli of five different

sizes were studied: 50-by-50 pixels (1.4-by-1.4 cm²)

to 250-by-250 pixels (7 x 7 cm²) by steps of 50

pixels.

All different sizes were tested with two

flickering frequencies: 15Hz and 30Hz, resulting in

ten different stimulus conditions.

2.5 Effect of Stimulus Shape

The effect of the five different checkerboard shapes

shown on Figure 1 was investigated. The

checkerboard size was 250 x 250 pixels, divided into

2

2n

squares, with n = 0, 1, …, 4.. As in the previous

case, two flickering frequencies (15Hz and 30Hz)

were investigated.

The subjects were presented with all 18

conditions in a randomized order, during one min for

each condition. The total recording time was

approximately 30 min.

The total duration of the experiment was about

one hour, including the installation of the EEG

electrodes.

Figure 1: Illustration of the five different stimuli used to

test the effect of shape.

2.6 Signal Processing

The discrete Fourier transforms of the signals were

computed, and the signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) were

estimated as:

SNR

argmax

〈

〉

Where

is an interval of ±0.1Hz in the Fourier

domain around the stimulus frequency,

is an

interval of ±0.5Hz around the stimulus frequency

excluding interval

, and

〈

⋅

〉

stands for the average.

The SSVEP peaks may not appear exactly at the

stimulation frequency due to hardware limits.

Consequently we use the interval

to find the

maximum peak nearby the stimulus frequency. SNR

is actually a way to enhance SSVEP peaks (Thorey

et al., 2012, Wang et al. 2006): it computes the ratio

of the SSVEP peak amplitude to the average Fourier

power of the background EEG.

Statistical analysis was performed using

multiway analysis of variance (ANOVA). Normality

of the data was controlled using a Lilliefors test.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1 Effect of Stimulus Size

As expected, the response and the signal-to-noise

ratio decrease significantly with stimulus size, for

stimuli at 15 Hz as well as stimuli at 30 Hz.

Nevertheless, SNR with a median value above 10

can still be observed for a size of 100-by-100 pixels.

This size effect is illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

EffectofStimulusSizeandShapeonSteady-StateVisuallyEvokedPotentialsforBrain-ComputerInterfaceOptimization

575

Figure 2: Boxplots of the Fourier power of the response to

a 15Hz stimulus (fundamental at 15 Hz, and harmonics at

30 and 45 Hz) vs. stimulus size. “p" is the ANOVA p-

value (p<0.05 indicates a significant difference between

the means of the observed Fourier powers). Red crosses

indicate outliers.

Figure 3: Boxplots of the SNR of the response to a 15Hz

stimulus (fundamental at 15 Hz, and harmonics at 30 and

45 Hz) vs. stimulus size. "p" is the ANOVA p-value

(p<0.05 indicates a significant difference between the

means of the observed SNR values). Red crosses indicate

outliers.

3.2 Effect of Stimulus Shape

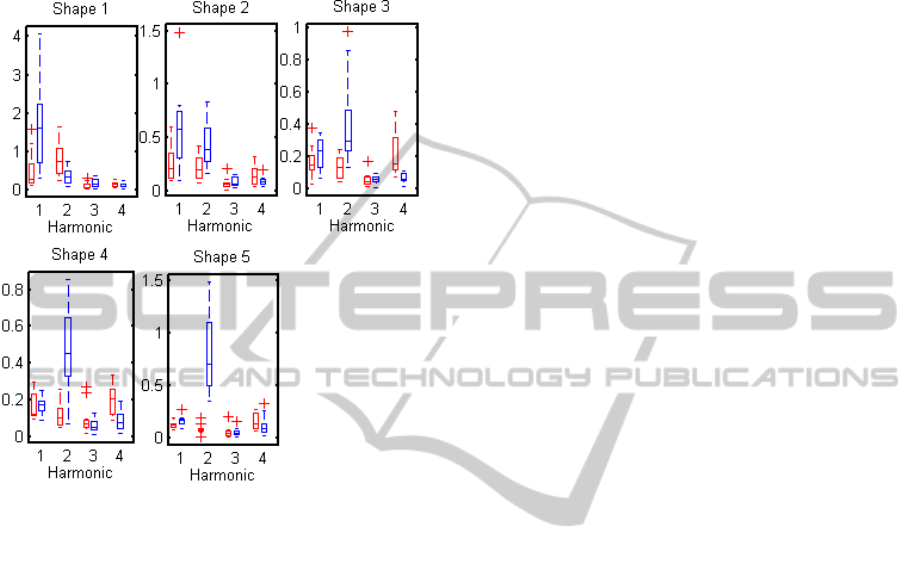

Figure 4 and Figure 5 show that the response

and the SNR decrease with increasing number

of checkerboard squares, but that the second

harmonic increases

. This result may be related to

the existence of two major visual pathways:

The parvo-cellular(PC) pathway, originating in

the midget retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), reacts

to the high contrast, shape, color and red/blue

information (e.g. Foxe et al. 2008). It is

assumed to correspond to tonic cells, which

generate the fundamental harmonics;

The magno-cellular (MC) pathway, originating

in the parasol RGCs. It is achromatic and reacts

to low contrast stimuli, especially moving

stimuli; it carries depth information. It is

assumed to correspond to phasic cells, which

generate the second harmonic (see for instance

McKeefry et al. 1996).

The observed second harmonic effect might be

accounted for by the fact that checkerboards with

many flickering areas stimulate preferentially the

MC pathway, while checkerboards with a small

number of flickering areas stimulate the PC pathway.

These assumptions will be substantiated by more

detailed experiments in the future.

Figure 4: Boxplots of the Fourier power of the response to

a 15Hz checkerboard stimulus (fundamental at 15 Hz, and

harmonics at 30 and 45 Hz) with the five shapes shown on

Figure 1. "p" is the ANOVA p-value (p<0.05 indicates a

significant difference between the means of the observed

Fourier powers). Red crosses indicate outliers.

Figure 5: Boxplots of the SNR of the response to a 15Hz

checkerboard stimulus (fundamental at 15 Hz, and

harmonics at 30 and 45 Hz) with the five shapes shown on

Figure 1. "p" represents the ANOVA p-value (p<0.05

indicates a significant difference between the means of the

observed SNR values). Red crosses indicate outliers.

The shape effect could be useful for brain-computer

interfaces, by allowing the use of stimuli having the

same flickering frequency but different shapes: the

stimulation by a plain rectangle can be discriminated

from the stimulation by a checkerboard by the fact

that the 1

st

harmonic of the response to the former is

more powerful than its 2

nd

harmonic, while the

reverse is true in the case of a checkerboard

stimulation (Figure 6). In the design of such a BCI

system, the commands would appear as the

IJCCI2013-InternationalJointConferenceonComputationalIntelligence

576

juxtaposition of commands represented by

rectangles together with commands represented by

checkerboards, but flickering at the same frequency

(thereby potentially doubling the number of possible

commands).

Figure 6: Fourier Power of the SSVEP responses to 30Hz

and 15Hz stimuli. 1/2/3/4 denote correspondingly the

frequencies 15Hz/30Hz/45Hz/60Hz (harmonics and

subharmonics of 30Hz stimulation may be observed at 15,

30 and 60Hz; and for 15Hz stimulation at 15, 30, 45 and

60Hz). Red boxes denote the Fourier powers in response

to a 30Hz stimulus; blue boxes denote the Fourier powers

in response to a 15Hz stimulus.

4 CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we observed that different size and

different type of shape of the stimuli change the

properties of SSVEP responses. The main

observation is the fact that a flickering checkerboard

elicits responses whose 2

nd

harmonic contain more

power than the first. This effect could be useful for

increasing the number of possible commands in

SSVEP brain-computer interfaces.

5 REFERENCES

Dawson, G. D., 1954. A summation technique for the

detection of small evoked potentials. Electroenceph.

Clin. Neurophysiol.1954; 6:65-84.

Foxe, J. J., Strugstad, E. C., Sehatpour, P., Molholm, S.,

Pasieka, W., Schroeder, C.E., McCourt, M.E. 2008.

Parvocellular and magnocellular contributions to the

initial generators of the visual evoked potential: high-

density electrical map-ping of the ‘‘C1’’ component.

Brain Topogr. 21 (1), 11–21.

Herrmann, C. S., 2001. Human EEG responses to 1–100

Hz flicker: resonance phenomena in visual cortex and

their potential correlation to cognitive phenomena.

Exp. Brain Res. 137 (3–4), 346–353.

McKeefry, D. J., Russell, M. H., Murray, I. J.,

Kulikowsky, J.J. 1996. Amplitude and phase

variations of harmonic components in human

achromatic and chromatic visual evoked

potentials.Vis. Neurosci. 13, 639–653.

Nicolelis, M. A-L., Wessberg, J., Stambaugh, C. R.,

Kralik, J. D., Beck, P. D., Laubach, M., Chapin, J. K.,

Kim, J., Biggs, S. J., Srinivasan, M. A. 2000. Real-

time prediction of hand trajectory by ensembles of

cortical neurons in primates. Nature 408 (6810): 361–

5.

Regan, D., 1989. Human Brain Electrophysiology: Evoked

Potentials and Evoked Magnetic Fields in Science and

Medicine. Elsevier, New York.

Silberstein, R. B., 1995. Steady-state visually evoked

potentials, brain resonances, and cognitive

processes.Nunez, P. L. (Ed.), Neocortical Dynamics

andHuman EEG Rhythms. Oxford University Press,

Oxford, pp. 272–303.

Tanaka, K., 1996. Inferotemporal cortex and object

vision.Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 109–139.

Tanaka, K., 1997. Mechanisms of visual object

recognition: monkey and human studies. Curr. Opin.

Neurobiol. 7 (4), 523–529.

Thorey, J., Adibpour, P., Tomita, Y., Gaume, A.,

Bakardjian, H., Dreyfus, G., Vialatte, F.B. 2012. Fast

BCI calibration – Comparing methods to adapt BCI

systems for new subjects. Proc. NCTA 2012,

Barcelona, Spain. IJCCI (NCTA) 2012:663-669.

Vialatte, F. B., Maurice, M., Dauwels, J., Cichocki, A.

2010. Steady-State Visually Evoked Potentials: Focus

on Essential Paradigms and Future Perspectives.

Progress in Neurobiology, 90(4):418-438.

Vialatte, F. B., Maurice, M., Dauwels, J., Cichocki, A.

Steady State Visual Evoked Potentials in the Delta

Range (0.5-5 Hz). 15th International Conference on

Neural Information Processing, ICONIP, Auckland,

New Zealand, November 25-28 2008. ICONIP 2008,

LNCS, Part I, 5506:399–406, published in 2009.

Wang, Y., Wang, R., Gao, X., Hong, B., Gao, S., 2006. A

practical VEP-based brain–computer interface. IEEE

Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 14 (2), 234–239.

EffectofStimulusSizeandShapeonSteady-StateVisuallyEvokedPotentialsforBrain-ComputerInterfaceOptimization

577