The Present and Future of Dynamic e-Health Interoperability in

Switzerland

Results of an Online Questionnaire

Visara Urovi and Michael I. Schumacher

Institute of Business and Information Systems, University of Applied Sciences of Western Switzerland, Sierre, Switzerland

Keywords:

e-Health, Semantic Interoperability, Dynamic EHR Echange, IHE, Interoperability Standards.

Abstract:

The research in the medical health care systems is shifting towards solutions that enable dynamic data ex-

change. To achieve this shift, interoperable solutions have been proposed by initiatives such as the integrating

Healthcare Enterprise (IHE). IHE focuses on defining interoperable solution by specifying recommendations

that foster standard based integration between healthcare systems. Using the results of an online questionnaire,

in this work we study the current use of standards in the health care systems of Switzerland. The question-

naire identifies four dynamic data exchange scenarios that enhance the interoperability and the integration

between different healthcare systems. The novelty of this work is that the identified scenarios are currently

not addressed by the IHE recommendations and, they can improve the current interoperability solutions. The

questionnaire confirms that those scenarios are useful and we suggest some technical solutions that may help

to achieve them.

1 INTRODUCTION

Electronic Health Records (EHRs) are electronic col-

lections of health information about patients (Gunter

and Terry, 2005). EHRs are easy to transfer and, if

linked to best-practice guidelines, they can support

care decisions (Grimson et al., 2000). Many of the

current EHR systems operate in a closed environ-

ment where patient’s EHRs can be dynamically ex-

changed only within the health organisation that cre-

ates them. As the focus of health care delivery shifts

from specialist centers to community settings (Kalra,

2006), new approaches are focusing on the integra-

tion of such records across the institutional bound-

aries (Wozak et al., 2008).

The health industry is recognizing the impor-

tance of dynamic exchange of EHRs by adopting in-

teroperability standards and by seeking integrations

with external platforms. In particular, the Integrat-

ing the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE)

1

is an initia-

tive that specifies guidelines on how healthcare pro-

viding systems can integrate and communicate more

effectively. IHE enjoys high acceptance due to its

practical complement to existing standards such as

HL7 CDA

2

. The IHE consortium specifies various

1

www.ihe.net

2

HL7 CDA is a standard supporting message-based in-

IHE Integration Profiles which define solutions to

specific problems. The Integration Profiles are con-

stantly checked against practical experiences and are

continuously adapted (Wozak et al., 2008). Despite

this, IHE lacks features to handle dynamic scenar-

ios where caregivers can dynamically connect and ex-

change data (IHE, 2008), and mechanisms on how pa-

tient’s data are found and exchanged are yet to be de-

fined.

Using an online questionnaire, this paper dis-

cusses the gap between the interoperability standards

and what healthcare system solutions are currently

missing in order to support the dynamic data ex-

change. The questionnaire confirms that there is a

gap between the use of interoperability standards and

the current ability to dynamically connect and share

patient data at a cross community level. The partici-

pants recognized as very important for health systems

to rely on interoperability standards and found useful

to have more dynamic scenarios for EHR exchange.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 intro-

duces the current standards and semantic dictionaries

defined in health care systems. Section 3 discusses

the focus of the survey, the recruiting of participants

and the design of the online questionnaire used for the

study. Section 4 illustrates the results of the question-

formation exchange of medical data www.hl7.org

244

Urovi V. and I. Schumacher M..

The Present and Future of Dynamic e-Health Interoperability in Switzerland - Results of an Online Questionnaire.

DOI: 10.5220/0004748902440249

In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health Informatics (HEALTHINF-2014), pages 244-249

ISBN: 978-989-758-010-9

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

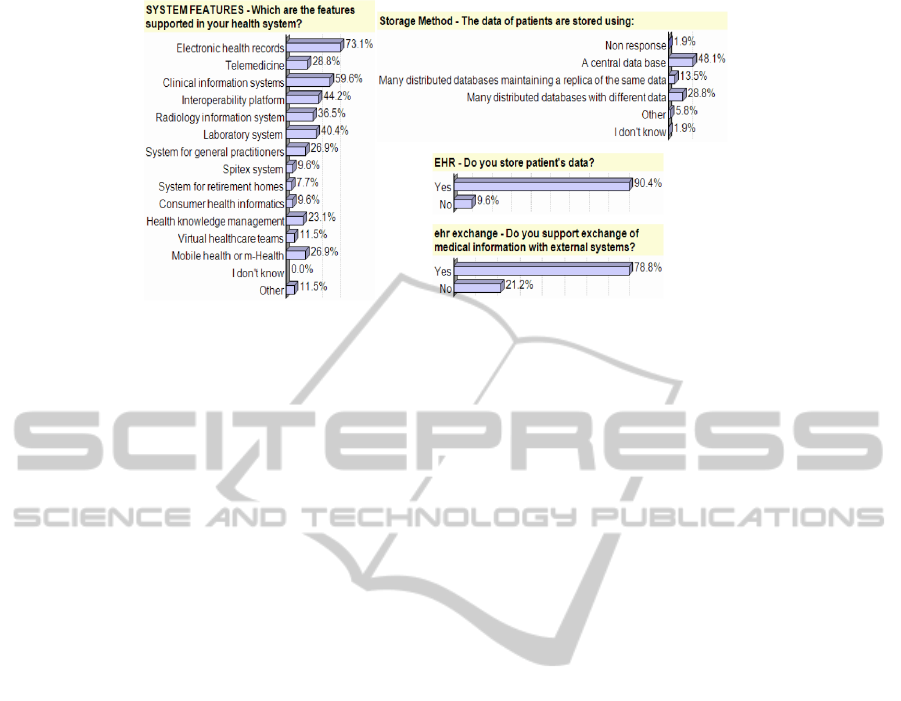

Figure 1: The characteristics of the represented systems.

naire. Section 5 discusses how future technical solu-

tions may drive interoperability in healthcare systems.

Finally, Section 6 summarizes this work.

2 SEMANTIC

INTEROPERABILITY

Semantic interoperability in a medical context means

that medical data are exchanged and processed in dis-

tributed systems by unambiguously sharing the mean-

ing of the document content (Reinhold et al., 2011).

Standard models for EHR exchange play a funda-

mental role for achieving semantic interoperability.

Among the standardisations efforts, the most adopted

nowadays have become HL7 (Dolin et al., 2001) and

OpenEHR (Garde et al., 2007), for structuring the

health data, IHE for defining the architectural as-

pects of EHR exchange, and SNOMED CT (Stearns

et al., 2001), LOINC (McDonald et al., 2003) and

MEDICINE (Goltra, 1997) as code based systems for

the medical terminology.

HL7 is a standard supporting message-based ex-

change of medical data. The most adopted HL7

standard is the HL7-Clinical Document Architecture

(HL7-CDA). HL7-CDA specifies the syntax and sup-

plies a framework for specifying the full semantics of

a clinical document. The focus of HL7 is in the mes-

sage exchange and not in the organization of the EHR,

thus this standard alone is not enough to achieve in-

teroperability. OpenEHR is standard that describes

the management, storage, retrieval and exchange of

EHR. Like HL7, OpenEHR proposes a set of models

for clinical data with the difference that the reference

model is based on building blocks and its underlying

modeling style is strictly object oriented, thus, solv-

ing several limitations of the message based exchange

model proposed by HL7-CDA. Healthcare terminolo-

gies such as SNOMED CT, LOINC and MEDICINE

define universal code names and identifiers to medi-

cal terminology. Their purpose is to associate codes to

medical terminology so that, if everyone was to share

them, it would be possible to share and automatically

understand the health data, such as the one exchanged

in HL7 messages.

The IHE Integration profiles are becoming the

glue to these standardization efforts. They com-

plement these standards with concrete recommen-

dations on how to achieve interoperability in terms

of how to construct the messages that enable data

to be exchanged and what are the actors that in-

volved in these interactions. There are many IHE

profiles that address interoperability between health

care systems. We focus on the ones that propose solu-

tions for EHR exchange (denoted as XC*), namely

Cross-Enterprise Document Sharing (XDS), Cross-

Community Access (XCA), Cross-Community Pa-

tient Discovery (XCPD) and Cross-Community Fetch

(XCF).

The XDS (IHE, 2011) profile defines how health

enterprises can inter-operate to share patient-relevant

documents by working as one health community with

the same set of policies, patient identifications and

security mechanisms. Since XDS does not resolve

document sharing among multiple communities, the

XCA profile specifies how medical data held by other

communities can be queried and retrieved. XCA as-

sumes that communities have pre-established agree-

ments, knowledge of one another and have ways to

know the correct patient identifiers in different com-

munities (IHE, 2008). XCPD locates communities

which hold patient’s relevant health data and trans-

lates patient’s identifiers across communities. XCPD

does not automate the discovery of communities and

it still requires communities to have pre-established

agreements for exchanging the documents. Finally

XCF defines a single transaction to retrieve a small

number of documents (ideally one). XCF requires

document properties to be known prior to the doc-

ThePresentandFutureofDynamice-HealthInteroperabilityinSwitzerland-ResultsofanOnlineQuestionnaire

245

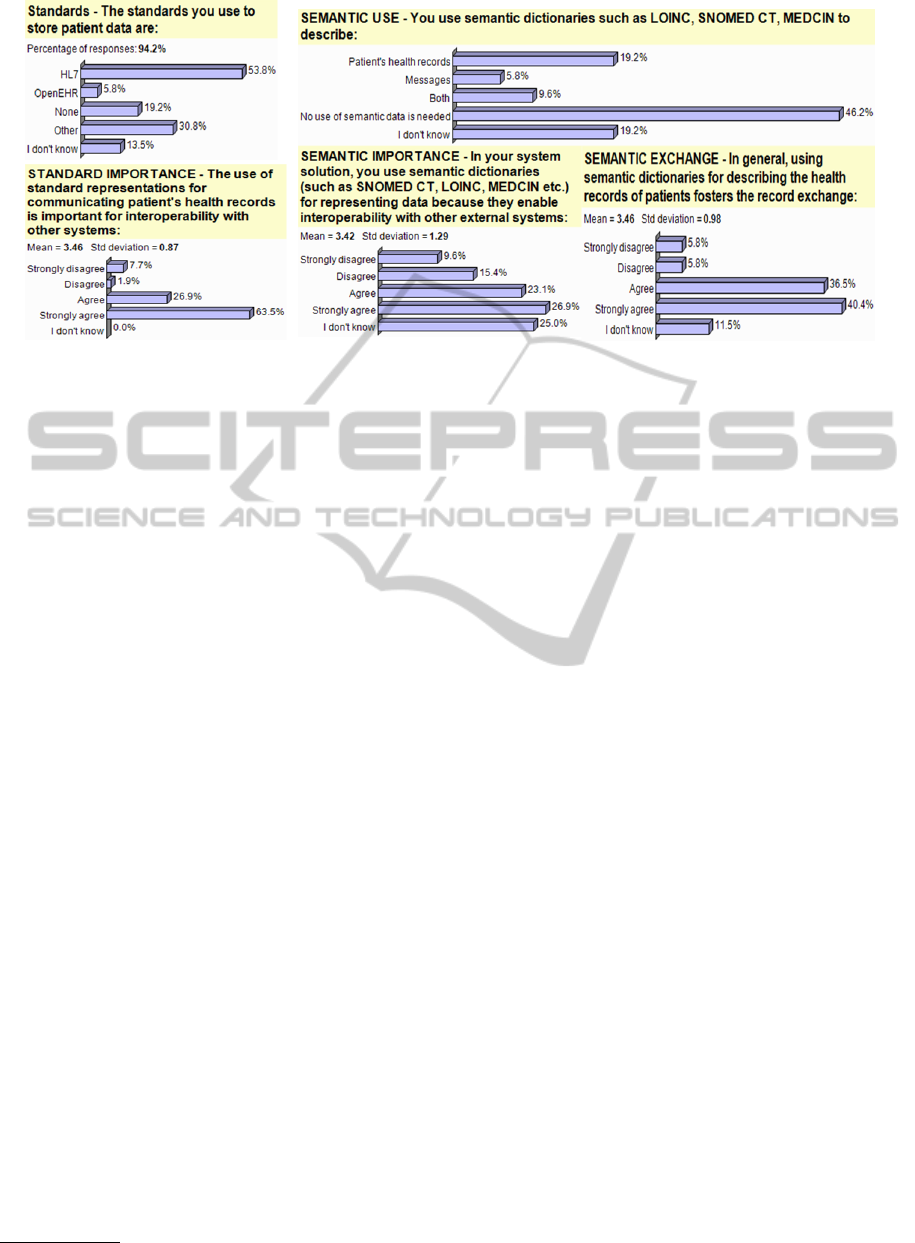

Figure 2: Standard’s use and importance. Figure 3: The use and importance of semantic dictionaries in EHR exchange.

ument retrieval. Other IHE profiles support cross-

community data exchange by providing: security

(Audit Trial and Node Authentication); privacy (Ba-

sic Patient Privacy Concent); mapping of user identi-

fications (Cross-Enterprise User Assertion); point-to-

point e-mail notification of updates (Notification of

Document Availability); and a consistent time (Con-

sistent Time). Not all of these profiles are manda-

tory to integrate in the healthcare systems that sup-

port cross-community document exchange, however

they provide important technical solutions for secure

interoperability at a cross-community level.

3 METHOD

Our study focuses on the use of interoperability solu-

tions in Switzerland. The health system in Switzer-

land is a combination of public (i.e. hospitals) and

private systems (i.e. private clinics) and health condi-

tions can be treated in any of the competent healthcare

providers. The Swiss Government has recently rec-

ommended the adoption of IHE profiles to achieve in-

teroperability. The first pilot deployments have been

released, such as the eToile project (Geissbuhler et al.,

2004) in Geneva and Infomed (Michelet et al., 2011)

in Valais. The objective of the questionnaire was to

find out the current state and the future directions with

regards to the dynamic EHR exchange.

The survey was based on an online questionnaire

which was sent to the Swiss eHealth summit

3

, a

leading event for ICT in medicine and healthcare for

Switzerland, with around 200 experts interested in

ways technology can improve medicine and health-

care in general.

Fifty two participants took part on the survey. The

3

http://www.ehealthsummit.ch/

majority of the participants (28.8%) were holding an

IT role, followed by 15.4% and 13.5% respectively

holding Chief Technology Officer, or Chief Execu-

tive Officer roles. These roles are very important for

our questionnaire as they can best answer the tech-

nical and strategical aspects of the represented sys-

tems. It also suggests to us that we met our target

audience for having relevant results within the scope

of the questionnaire. We asked the participants about

their represented system, the use of standards and how

interoperable their systems is. Figure 1 summarizes

the features of the systems represented by the partic-

ipants. The majority were systems dealing with EHR

and with clinical information (73.1% and 59.6% re-

spectively). Also, 44.2% of the participants said that

their represented system solution provides a solution

to interoprerability. Storage of EHR accounted for

90.4% with 78.2% also supporting EHR exchange.

The storage of EHR was mostly done within a cen-

tral database (49%). The results described in Section

4 are based on what the participant said about these

types of systems.

In order to specify future directions in terms of

healthcare interoperability, we defined four scenarios

that were drawn from an analysis of the state of the

art, with specific focus into what is currently missing

in the IHE interoperability solutions. The scenarios

were described as follows:

• Scenario 1: A patient is treated in the hospital A,

rather than the hospital B of its residence area.

The system of hospital A can find the patient’s

data in the system of hospital B without prior in-

tegration between the two.

• Scenario 2: A patient is treated in the hospital A,

rather than the hospital B of its residence area.

Hospital A creates new health records on the pa-

tient. The Hospital A, upon patient’s consent,

HEALTHINF2014-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

246

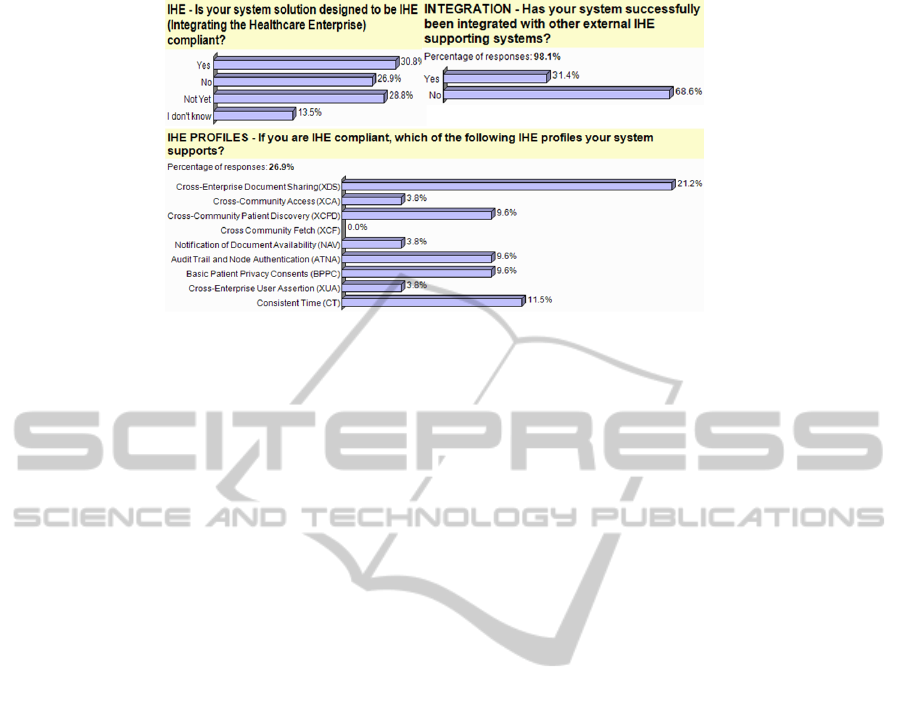

Figure 4: The use of IHE Interoperability Standards.

automatically updates the system B about these

records.

• Scenario 3: A patient is treated in the hospital

A. This patient has chosen that all the updates

concerning his health should be sent to hospital

B. The Hospital B collects all the updates on the

health of its patients.

• Scenario 4: A Hospital B receives health updates

on one of its patients. This patient has agreed that

his general doctor should receive these updates as

well. Hospital B, upon patient’s consent, automat-

ically propagates updates on patients to subscrib-

ing clinics.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Interoperability in Swiss Healthcare

Systems

We asked what are the general trends towards interop-

erability? We focused on three factors that combined

are known to foster integration within heterogenous

health platforms, namely the use of standards, the use

of semantic dictionaries and the use of IHE profiles

for standard system architectures. We were interested

to know the acceptance level of the existing standards.

For this reason, we asked what standards were used to

store patient data. Figure 2 shows that 63.5% agreed

that standards are important for interoperability with

other systems and, the most used standard for stor-

ing patient related data was HL7 (53.8%). The use of

HL7 standard is highly recommended in the current

IHE profiles. The result shows that the adoption of

IHE interoperability solutions is possible.

In order to measure the extend to which semantic

dictionaries are used in today’s Swiss healthcare set-

tings we asked the participants if, in their represented

systems: i) semantic dictionaries were used to de-

scribe data, ii) if the reason for their use was to enable

interoperability and iii) if the participants believed

that using the semantic dictionaries fosters record ex-

change. Figure 3 shows the results to these three ques-

tions. The majority of the participants (46.2%) did not

recognize the use of semantic data to be needed in de-

scribing patient health records or messages. This may

be due to the fact that most of the data exchanged with

external systems still requires human intervention and

automated data exchange has a long way to go. The

26.9% and 23.1% of users did respectively strongly

agreed and agreed that the use of semantic dictionar-

ies in their system was made to enable interoperabil-

ity with external systems. Additionally, 40.4% and

36.5% respectively strongly agreed or agreed that se-

mantic dictionaries, if used to describe EHRs, foster

their exchange.

In order to find out to what level the existing IHE

interoperability solutions are integrated in the current

health care systems, we asked if the represented sys-

tems were IHE compliant. Participants were given the

possibility to express interest in using IHE in the fu-

ture by answering ”Not Yet”. We considered that the

IHE adoption is quite new with respect to the digi-

talization of the EHR and that these systems may, in

the future, adapt to interoperate with other healthcare

systems. We also asked what specific IHE profiles

were supported and if they had been integrated with

other external IHE compliant systems. Figure 4 sum-

marizes the results which show that i) the use of IHE

accounted for 30.8%, however, another 28.8% indi-

cated an intention of using them, ii) In Switzerland,

the IHE profiles that support EHR exchange are be-

ing adopted. XDS is the most used (21.2%) because

it supports document exchange at the health organiza-

tion level. iii) 30.8% of the participants said that there

had been successful integration(s) with other external

IHE supporting system(s).

ThePresentandFutureofDynamice-HealthInteroperabilityinSwitzerland-ResultsofanOnlineQuestionnaire

247

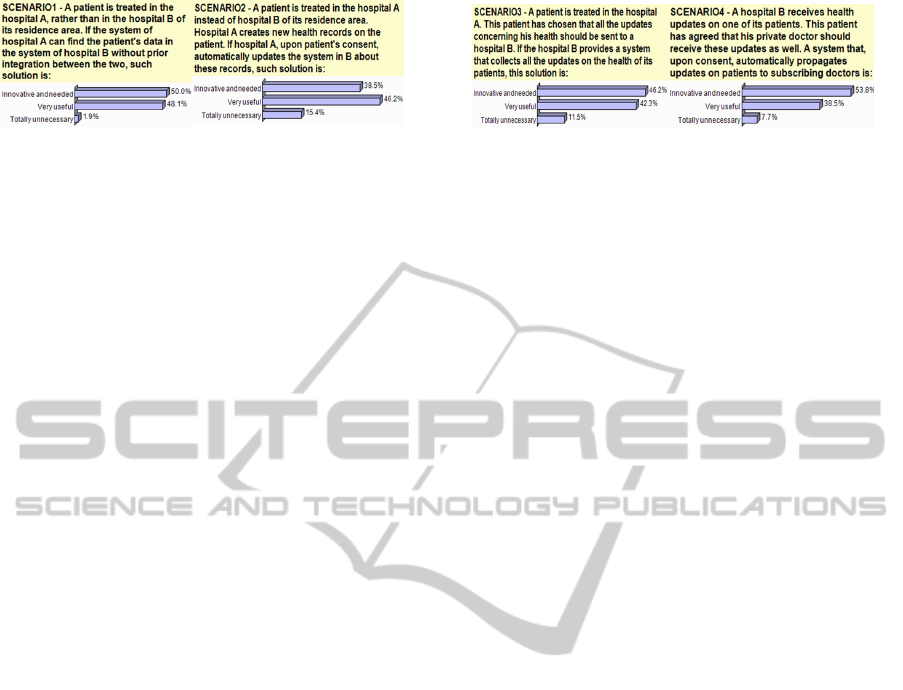

Figure 5: The results for Scenario 1 and 2. Figure 6: The results for Scenario 3 and 4.

4.2 Future Interoperability Scenarios

In order to find out what are the trends with respect to

interoperability solutions in health care systems, we

asked the participants to determine if the scenarios

presented in Section 3 were innovative, very useful

or unnecessary. Only one response was possible. A

distinction between innovative and useful was done

in order to determine if the scenarios were novel for

the participants as opposed to a useful feature which

already may exist in some systems.

Figure 5 and 6 show that all the scenarios are well

received with an average of 84.7-98.1% of partici-

pants finding the four scenarios either innovative or

very useful. The first scenario was the most impor-

tant feature with 50% finding the scenario innovative,

48.1% very useful and 1.9% finding it as unnecessary.

This result confirms that being able to dynamically

view data of patients held in other healthcare settings

is very beneficial.

5 DISCUSSION

The results of the questionnaire show that there is a

need to exchange data in more dynamic settings. The

realization of the four proposed scenarios requires

health communities to adopt standard approaches and

enable solutions for sharing their EHR in open and

dynamic settings. Some attempts in this direction

have already been done. The epSOS project pro-

vides cross-border health-services to patients seek-

ing healthcare in different countries from their own.

In Switzerland, e-Toile project proposes an universal

information exchange service for e-Health that cov-

ers a geographic area (Geneva). SemHealthCoord

project defines an architecture that enhances the cur-

rent IHE profiles with more dynamic EHR exchange

solution (Urovi et al., 2013). Presenting these works

is out of the scope of this paper, but it suffices to say

that all of those recent works rely on IHE profiles for

the data exchange. It is also worth noting that, for the

achievement of the four scenarios, ethical, legal and

security aspects must be investigated as much as the

challenges of the technical solution.

From a technical viewpoint, in addition to provid-

ing integration through use of standards, the results

suggest two key components that are important for

designing interoperable healthcare system solutions:

(a) dynamicity and (b) scalability. A dynamic solu-

tion supports EHR exchange with functions for find-

ing EHRs of patients independently from the system

that creates and stores them while a scalable solution

is needed to optimize the time and effort to find and

exchange EHRs.

A dynamic model for EHR exchange requires so-

lutions that address the semantic interoperability be-

tween heterogeneous healthcare systems. By provid-

ing semantic descriptions of the data held in other

health oganisations, it is possible to facilitate the in-

terpretation and sharing of the health data (Hendler,

2001). The semantic interoperability enables local

processing of the shared data; and it is also a prereq-

uisite for intelligent decision support and care plan-

ning (Schloeffel et al., 2006). In this context, the

agent technology brings advantages to interoperabil-

ity of the health care solutions such as high adapt-

ability in front of changes, distributed management

of sources and remote access to patient data (Isern

et al., 2010). In fact, agent-based systems can perform

distributed communication and reason with semantic

knowledge, thus enabling EHR sharing between such

heterogeneous systems. Finally, to support the dy-

namics of the scenarios here defined, common coordi-

nation models are needed in order to decouple the in-

teractions within different health organizations (Urovi

et al., 2013).

Scalability on a dynamic network of health com-

munities can be achieved by overlaying a Peer to Peer

(P2P) network (Androutsellis-Theotokis and Spinel-

lis, 2004) to link the heterogeneous health organi-

sation’s systems as peers (Kilic et al., 2010). The

P2P allows communities to interact on top of existing

network configurations without a central dependency.

With the right P2P network configurations, the time

to answer queries can be logarithmic with a growing

number of peers (Androutsellis-Theotokis and Spinel-

lis, 2004). The use of P2P technology in health care

settings is a novel concept (Guo et al., 2011) and it

requires security and privacy considerations. There

are many factors to consider, from sharing confiden-

tial information in a secure manner, to guaranteeing

the proper use of the EHRs. All these aspects require

HEALTHINF2014-InternationalConferenceonHealthInformatics

248

the security to be focal point to the design of such so-

lutions because it will determine if these frameworks

will, in the future, have a practical value.

6 CONCLUSIONS

We presented a study of the current situation and of

the future directions in dynamic interoperable solu-

tions for healthcare systems. We focused on the re-

sults of an online questionnaire collected from the

participants of the Swiss eHealth summit. The re-

sults showed a general trend towards the use of IHE

and HL7 which is a good indicator of solutions that

can support integration with other systems. The re-

sults also suggested that the future interoperability

will require more dynamic and open solutions to-

wards record exchange. Finally we discussed some

technical solutions that can make the difference to-

wards supporting these future scenarios. As part of

our future work, we plan to further investigate the im-

plications of the four proposed scenarios. The techni-

cal solution is only one aspect of realising these sce-

narios. We plan to study what are the practical, legal

and ethical aspects that may prevent institutions to go

towards more dynamic settings and how to overcome

them. Including issues of depersonalization and min-

imization of data and the way these can be integrated

in cross-institutional IHE settings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was funded by the Switzerland FNS grant

nr. 200021 135386 / 1.

REFERENCES

Androutsellis-Theotokis, S. and Spinellis, D. (2004). A sur-

vey of Peer-to-Peer content distribution technologies.

ACM Comput. Surv., 36(4):335–371.

Dolin, R. H., Alschuler, L., Beebe, C., Biron, P. V., Boyer,

S. L., Essin, D., Kimber, E., Lincoln, T., and Matti-

son, J. E. (2001). The HL7 Clinical Document Archi-

tecture. Journal of the American Medical Informatics

Association, 8(6):552–569.

Garde, S., Knaup, P., Hovenga, E., and Heard, S.

(2007). Towards semantic interoperability for elec-

tronic health records–domain knowledge governance

for open ehr archetypes. Methods of information in

medicine, 46(3):332–343.

Geissbuhler, A., Spahni, S., Assimacopoulos, A., Raetzo,

M., and Gobet, G. (2004). Design of a patient-

centered, multi-institutional healthcare information

network using Peer-to-Peer communication in a

highly distributed architecture. Medinfo, 11(Pt

2):1048–52.

Goltra, P. S. (1997). MEDCIN: a new nomenclature for

clinical medicine. Springer.

Grimson, J., Grimson, W., and Hasselbring, W. (2000). The

SI challenge in health care. Commun. ACM, 43:48–55.

Gunter, D. T. and Terry, P. N. (2005). The emergence of

national electronic health record architectures in the

united states and australia: Models, costs, and ques-

tions. J Med Internet Res, 7(1):e3.

Guo, Y., Hu, Y., Afzal, J., and Bai, G. (2011). Using

P2P technology to achieve eHealth interoperability. In

Service Systems and Service Management (ICSSSM),

pages 1 –5.

Hendler, J. (2001). Agents and the Semantic Web. IEEE

Intelligent Systems, 16:30–37.

IHE (2008). White paper: Cross community infor-

mation exchange. http://www.ihe.net/ Techni-

cal Framework/upload/IHE ITI TF White Paper

Cross Community 2008-11-07.pdf.

IHE (2011). Technical framework integration profiles vol 1.

http://www.ihe.net.

Isern, D., Snchez, D., and Moreno, A. (2010). Agents ap-

plied in health care: A review. International Journal

of Medical Informatics, 79(3):145 – 166.

Kalra, D. (2006). Electronic health record standards. vol-

ume 45, pages 136–144. Methods Inf Med.

Kilic, O., Dogac, A., and Eichelberg, M. (2010). Provid-

ing interoperability of ehealth communities through

peer-to-peer networks. Information Technology in

Biomedicine, IEEE Transactions on, 14(3):846–853.

McDonald, C. J., Huff, S. M., Suico, J. G., Hill, G.,

Leavelle, D., Aller, R., Forrey, A., Mercer, K., De-

Moor, G., Hook, J., et al. (2003). LOINC, a universal

standard for identifying laboratory observations: a 5-

year update. Clinical chemistry, 49(4):624–633.

Michelet, C., Fragnire, F., and Gnaegi, A. (2011). Infomed,

dossier patient partag en Valais. Journal of Swiss

Medical Informatics, 72.

Reinhold, S., Henning, M., Dominik, A. and Patrick, R.

2011. e-Heallth Semantic and Content for Switzerland

Schloeffel, P., Beale, T., Hayworth, G., Heard, S., and

Leslie, H. (2006). The relationship between cen 1360

6, hl7 and openehr. HIC and HINZ Proceedings, 24.

Stearns, M. Q., Price, C., Spackman, K. A., and Wang, A. Y.

(2001). SNOMED clinical terms: overview of the de-

velopment process and project status. In Proceedings

of the AMIA Symposium, page 662. American Medical

Informatics Association.

Urovi, V., Olivieri, A., Bromuri, S., Fornara, N., and

Schumacher, M. (2013). A P2P Agent Coordination

Framework for IHE based Cross-Community Health

Record Exchange. In ACM 28th Symposioum on Ap-

plied Computing, page to appear.

Wozak, F., Ammenwerth, E., Hoerbst, A., Soegner, P., Mair,

R., and Schabetsberger, T. (2008). IHE based Interop-

erability - Benefits and Challenges. volume 136 of

Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, pages

771–776. IOS Press.

ThePresentandFutureofDynamice-HealthInteroperabilityinSwitzerland-ResultsofanOnlineQuestionnaire

249