A Study on the Permeation and Scope of ICT Intervention

at the Indian Rural Primary School Level

Shrabastee Banerjee

1

, Kalyan Sankar Mandal

2

and Priyadarshini Dey

3

1

Department of Economics, The University of Warwick, Coventry CV4 7AL, U.K.

2

Centre for Contemporary India Studies, Lund University, Paradisgatan 2, 221 00, Lund, Sweden

3

Social Informatics Research Group, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, Joka, Calcutta, 700104, India

Keywords: ICTs in Education, Tribal Communities, Remote Teaching, e-Learning.

Abstract: The provision of education for all in India remains a distant dream, despite substantial amounts of

government and state investment going into it. The objective of this study is to highlight an alternative

learning model that makes use of the e-revolution that has proliferated into every aspect of our lives.

Although there have been attempts to incorporate ICT into rural classrooms, most of the focus has been on

video-based digitized learning and has not efficiently addressed the best ways in which learning can be

achieved. Our aim is thus to design a model that not only makes e-learning effective, but replaces the under-

qualified teachers in remote areas and allows for the free permeation of education in ways that might bridge

the digital divide amongst students of various socio economic backgrounds. In this context our intervention

focuses on a class of 16 students, 10 to 11 years of age (class 5) at Ma Sarada Shishu Tirtha, a school for

tribal girls, located in Krishnanagar, West Bengal, India. The intervention involved a remote teacher

delivering Math and English lessons in a class-room setting, (via the video conferencing software Skype,

and PowerPoint Presentations) while also making the session interactive.

1 INTRODUCTION

Elementary education of underprivileged rural

children residing in remote regions is the primary

focus of the study, since only a robust elementary

education system can solve chronic problems of low

literacy and educational deprivation. Even though

global demand tends to be focused on higher

education and technical skills, there are backward

linkages with elementary education in several ways.

On the one hand, achieving universal elementary

education is expected to raise productivity and

incomes and strengthen the domestic market, seen as

a condition for continued economic growth. On the

other hand, the growing concern with basic

education is seen as limited in the current economic

scenario as it does not adequately consider the

education and skill requirements needed to enhance

productivity and incomes in a changing economy.

Development theory in recent years has taken

note of the importance of education as an index of

development of a nation, and with its myriad

positive effects on the functioning of a society, the

outreach of education to every stratum of society is a

subject of great concern. The connection between

universalisation of elementary education and human

development is one of the most widely

acknowledged issues in public discourse across the

globe. Elementary education thus plays a pivotal

role in reducing social inequalities by expanding

human capabilities. (Sen, 1989)

Four features that have characterized India since

Independence continue to characterize India’s

elementary education system: incomplete enrolment,

inequalities, poor quality, and ineffective school

performance. Further, despite aggregate

improvements in education levels, glaring

inequalities in basic education continue to persist.

Disparities between regions (states) and across

gender, caste, class, religious groups; and other

marginalized sections of society continue to present

the biggest challenge for policy makers and

educationists (Dreze and Sen, 2002). For instance,

about 53 % boys complete primary education

compared to 34% girls. Recent interventions have

helped in bridging the gender gap but the drop-out

rate among girls, especially in primary classes, is

still a cause for grave concern. This is reflected, for

363

Banerjee S., Sankar Mandal K. and Dey P..

A Study on the Permeation and Scope of ICT Intervention at the Indian Rural Primary School Level.

DOI: 10.5220/0004763303630370

In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Supported Education (CSEDU-2014), pages 363-370

ISBN: 978-989-758-021-5

Copyright

c

2014 SCITEPRESS (Science and Technology Publications, Lda.)

instance, in the differential in the median years of

schooling which is 5.5 years for boys compared to

1.8 years for girls.

Marginalized groups such as the scheduled castes

(SCs) and scheduled tribes (STs) (two groups of

historically-disadvantaged people recognised in

the

Constitution of India) as well as religious

minorities continue to fall out of the loop of

schooling. In addition, there are striking gender

differentials in school attendance among children 6–

14 years belonging to SC, ST, and rest of India. The

gender differential is most pronounced among the

ST communities—a gap of almost 12 percentage

points (Kumar and Rustagi, 2010).

School performance is often marked by

absenteeism, inadequately trained teachers with

indifferent attitudes, non-availability of teaching

materials, inadequate supervision, and little support.

Many poor families, having lost faith in government

schools, are forced to send their children to private

schools even when they have access to ‘free’ public

schools. Several cases of discrimination are reported

– against girls, against children belonging to socially

disadvantaged and minority communities, and

against the poor. Corporal punishment is common

and many children are afraid of going to school for

fear of being beaten, if not publicly ridiculed or

rebuked by teachers and other students. (Kumar and

Rustagi, 2010)

Although the proportion of GNP allocated to

education (revenue and capital accounts together)

has grown from a very low level of 0.67 % in 1951-

52 to reach the all-time high of 4.4 % in 2001, mass

illiteracy continues to flourish. Education is by far

the largest capitalized space in India with $30bn of

government expenditure (3.7% of GDP; at global

average), and a large network of around one million

schools and 18,000 higher education institutes. Yet,

the public education system is ‘insufficient’ and

‘inefficient’. A break-up of government expenditure

shows that only a miniscule 0.82% component goes

towards capital expenditure. A whopping 80% of the

revenue expenditure on teachers’ salaries leaves

little to be spent on infrastructure creation, which

eventually translates into ‘ineffective’ infrastructure/

quality of education. (Vora and Dewan, 2009). It

indicates that a higher allocation of funds on

education is not the only criterion to solve our

literacy problems.

Although, various schemes and programmes

have been started by the State Governments and the

Ministry of Tribal Affairs to promote universal

primary education among tribals such as- scheme for

establishment of Ashram schools in tribal sub-plan

areas, scheme for establishment of boys hostels for

the Scheduled Tribes, scheme for construction of

girls hostels for the Scheduled Tribes, and scheme

for development of Primitive Tribal Groups (PTG),

but in reality very few of them have percolated down

to the tribal and benefited them. Many of the

programmes did not benefit the tribal community

because the programmes were not contextualized

and localized considering regional, geographical and

physical differences and barriers. (Kumar, 2008)

ICTs are a potentially powerful tool for

extending educational opportunities, both formal and

non-formal, to previously underserved

constituencies—scattered and rural populations,

groups traditionally excluded from education due to

cultural or social reasons such as ethnic minorities,

girls and women, persons with disabilities, etc.(Roy,

2012)

ICT based distance education in India has

primarily been confined to university-level

education and is often considered being sub-par

when compared to traditional courses. The long-term

purpose of the present study is to develop a

sustainable model of distance-learning that is cost-

effective, and leads to a more fulfilling learning

experience for the children.

The objective of this study is to highlight the

importance of working with constrained resources,

and proposes an alternative learning model that

makes use of the e-revolution that has proliferated

into every aspect of our lives. The study examines

whether it can be utilised to overcome infrastructural

bottlenecks in the provision of quality education in

inaccessible rural areas, and thus bring about a

concomitant increase in the population’s educational

levels. The internet-based social media revolution of

the present age has the possibility of transforming

education and knowledge as one knows it. By

exploiting this, it may be possible, via a model that

combines the correct elements of distance learning,

to bring forth a knowledge revolution and spread

education to the remotest corners of the country. Our

aim is thus to design a model that not only makes e-

learning effective, but replaces the under-qualified

teachers in remote areas and allows for the free

permeation of education in ways that might bridge

the digital divide amongst students of various socio

economic backgrounds.

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

364

2 ICT BASED LEARNING

2.1 Computer-Assisted Learning

The wide use of Internet has affected the methods of

education, giving us the concept of global classroom

where any number of students can interact with each

other at any time. ICT is currently widespread in

schools and colleges of developed countries (DG

Communications Networks Report, 2013). In the

developing countries, it is being primarily used to

support education in the form of “E-Learning”

applications. There is still some amount of

scepticism among the schools in adopting ICT

because it is still a relatively new feature and its

impact on student achievement is not known. Also

such technological solutions are thought to be not

very cost effective (Rajesh, 2003).

Although there are several studies that indicate

how ICT can benefit various stakeholders, what is

certain is that ICT is not the ultimate solution rather

an aid to achieve the maximum that can be derived

out of educational experiences at school. While the

debate on the impact of ICT on learning outcomes

still goes on, there seems to be a consensus that ICTs

in education can increase access to information

inside a classroom as well as increase motivation

and efficiency throughout the system. (Haddad and

Jurich, 2002) (InfoDev Report, 2010)

Government of India, as part of its 11th Five

Year Plan, continues to support federally sponsored

scheme, known as “Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, (SSA)”

with the objectives of providing school education to

every child between the age of 6 and 14 years and

improving the quality of school education in the

country. Under this policy GOI aims at fostering

ICT based Education in India. Under the Sarva

Shiksha Abhiyan, several Computer Aided Learning

(CAL) programmes have been created by

developing multimedia content

.

1

The objectives of CAL are as follows:

1. To facilitate effective delivery of curriculum

content

2. To act as an effective supplement for teachers to

improve learning levels in the school since it

facilitates practical and experimental learning.

3. To serve as a means to attract children to schools

with the multimedia i.e. audio-visual form of

learning on various subjects of classroom

teaching and thus hold their attention, hence

tackling the challenge of dropouts and

achievement of enrolment.

1

(www.ssa.tn.nic.in/Docu/CAL%202011-ss.pdf)

SSA has introduced many CAL projects across

states in India. 27,289 schools with about 5.3 million

students were beneficiaries of this program.

2

The

two major ICT related projects in schools are

Multimedia in K-12 (for affluent private schools)

and ICT in public schools. The leading players are

Educomp Solutions, Everonn and NIIT. Educomp

which is the pioneer in this field has a product called

“Smart Class”. Smart class is a product offered

under Multimedia in K-12. The objectives of this are

as follows:

1. To use multimedia modules to effectively teach

students across Kindergarten to 12

th

grades.

2. Content delivery through multimedia i.e. digital

content and LCD TVs/Projector assisted

whiteboards. It has been universally accepted that

this content delivery scheme improves teaching

and learning experience.

However, the focus of these efforts was more

towards computer-aided learning than Distance e-

Learning . Distance E-Learning is the combination

of Distance Education and e-Learning which is

characterized by the extensive use of Internet

enabled web technology in the delivery of education

and instruction and the use of synchronous and

asynchronous online communication in an

interactive learning environment or virtual

communities, in lieu of a physical classroom, to

bridge the gap in temporal or spatial constraints

(Garrison, 2011). A recent development in distance

e-learning is Massive open online

courses (MOOCs), aimed at large-scale interactive

participation and open access via the web or other

network technologies.

But, MOOC is usually non-interactive, i.e. the

students will be viewing the recorded videos by the

instructors, followed by off-line question-answering.

Our focus in this study is to use Distance e-Learning

in a synchronous mode, which implies real-time

interaction with fixed-time-fixed-place virtual

classroom over the Internet for primary students.

The McKinsey report (Madgavkar et al, 2012)

states that there will be 330 million Indian users of

the internet in 2015, thus making it the second

largest connected population in the world. Rural

access to education can be vastly improved by

means of exploiting this revolution, and creating a

networked virtual classroom system.

2.2 ICT Interventions in Rural

Classroom

Some efforts in the sphere of remote learning

2

mhrd.gov.in/ict_school

AStudyonthePermeationandScopeofICTInterventionattheIndianRuralPrimarySchoolLevel

365

already undertaken in rural India are summarised as

follows:

Hole-in-the-Wall (HitW): Hole-in-the-Wall is a

‘Shared Blackboard’ which children in

underprivileged communities can collectively own

and access,” to express them, to learn, and to explore

together.” In an experiment conducted first in 1999,

a computer was placed in a kiosk created within a

wall in a slum, and children were allowed to use it

freely. The experiment aimed at proving that

children could be taught by computers very easily

without any formal training. Sugata Mitra, the

inventor, termed this as Minimally Invasive

Education (MIE). The experiment has since been

repeated in many places, HIW has more than 23

kiosks in rural India. This work demonstrated that

groups of children, irrespectively of who or where

they are, can learn to use computers and the Internet

on their own with public computers in open spaces

such as roads and playgrounds, even without

knowing English.

Pratham’s Computer Aided Learning: This is a

school based program which caters to school going

children from 6-18 age groups with about 40%

children in secondary school age. The objective of

this program is: 1) To impact children’s basic

learning levels using IT and 2) to give them relevant

IT knowledge and skills. Through its school based

computer labs, this program reaches out to close to

90,000 children across 7 states. This program also

tries to improve schools performance by

encouraging them to adopt various IT solutions like

MIS, Database etc and to get teachers to adopt

technology through teacher training. The curriculum

includes software developed by Pratham in local

languages that helps build the reading and math

skills of the children.

Some other interventions have been observed in

the sphere of remote teaching and learning, though

the focus of the following is not rural:

1. Board of Open Learning School: This was

intended to be a medium for making distance

learning easy for students who are unable to

attend regular classes.

3

2. iPerform: It is a web-based e-learning platform

that works as an extension of the classroom and

provides a personalised self-learning

environment for students. It has been designed to

meet differential learning styles, engaging

students in activities like homework, revision

and even help in preparation of exams.

4

However, all these methods are mostly focusing on

3

www.bolsd.in

4

www.iperform.classteacher.com

asynchronous learning based on preloaded course

material and scope for real-time interaction are

absent. As discussed, our focus is synchronous, i.e.

virtual classroom over internet, where teacher should

be present at remote location during teaching..

2.3 Critical Evaluation of ICT

Intervention

A variety of constraints (Rajesh, 2003) dodge

India’s efforts to deploy technology in education:

1. Policy and Government commitment are existent

but all is lost on the road to implementation.

Educational projects, set up by conventional

governments as part of a broad educational

agenda, tend to reflect the conventionalism of

existing institutions with their hierarchical and

bureaucratic systems of administration when the

need is for creative and innovative management.

2. Access and availability of technology is another

issue as various implementing agencies that need

to cooperate are not coordinating enough. Lack

of stable electric power, non-existent or

unreliable telecommunication lines and a

mismatch between funding allocation and actual

needs all add to the problems.

3. Sustainability is also a major obstacle, with many

initiatives failing because Governments have not

anticipated the cost of maintenance and

upgrading of technology and services.

4. Geographic, Demographic and Climatic factors

affect the access, reach and implementation of

infrastructure

5. Ethnic and Cultural factors have an influence on

the teaching or pedagogical methods. Language

barriers are major obstacles as well.

Most importantly, however, the proper means for

implementing an ICT-backed educational model has

not been developed, with undue attention being paid

simply on the process of setting up ICT labs. Our

study tries to approach this issue in a manner that

can solve these basic problems to bring about the

complete benefits of an ICT intervention.

3 THE INTERVENTION AT A

TRIBAL SCHOOL IN INDIA

The long-term purpose of the study would be to

develop a sustainable model of distance-learning

that is cost-effective, and leads to a more fulfilling

learning experience for the children. The study

focuses on a class of 16 students of class V and 28

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

366

students of Class I of Ma Sarada Shishu Tirtha,

hailing from the tribal community in Krishnanagar,

India. The undertaken intervention involved a

remote teacher delivering Math and English lessons,

(via the video conferencing software Skype, and

PowerPoint Presentations shown during the video

conference) while also making the session

interactive and addressing individuals students

directly by name, which brought the additional

dimension of familiarity and added to the success of

the intervention. The survey finds sufficient

evidence to suggest that ICT intervention can

significantly enhance and improve their academic

attainment and leads to a more fulfilling learning

experience for the children. Further, the present

model is not one of distance learning in the

conventional sense, in that it combines elements of

traditional classroom teaching in a virtual form,

enhancing it with tools as and when required. The

main aim is to design a model that not only makes e-

learning effective, but to replace the traditional

model to save recurring expenses on local teachers

and allow for the free permeation of education in

ways that might bridge the digital divide amongst

students of various socio economic and other

geographical barriers.

For a preliminary understanding of the current

level of the children, tools developed by Pratham, an

NGO based in Mumbai, India were used. The

ASER Centre of Pratham seeks to use simple yet

rigorous methods to generate evidence on scale on

the outcomes of social sector programs. (Vagh,

2009). We have also conducted written and oral

examination to assess the effect of ITC intervention.

The before study comprised of usage of the

ASER tools, a questionnaire to assess the academic

achievement of the children. The children’s past

school results were also used to assess the baseline

standard. Upon using the ASER tools, it was

discovered that, while the children were fluent

readers in Bengali, their mathematical ability was

below average, with only 50% of the students being

able to solve Class 2 level division problems. The

questionnaire further revealed that English and Math

remained a major concern for the students.

During the intervention, Math and English

lessons were conducted for class V and English

lessons were conducted for class I remotely, via the

video conferencing software Skype, and PowerPoint

Presentations shown during the video conference.

(The intervention was preceded by a short

introduction session to make the students feel at

ease.) After the intervention, a follow-up

questionnaire was used using some exercises

covering the topics taught via ICT, to gauge their

interest, retention and possible improvement.

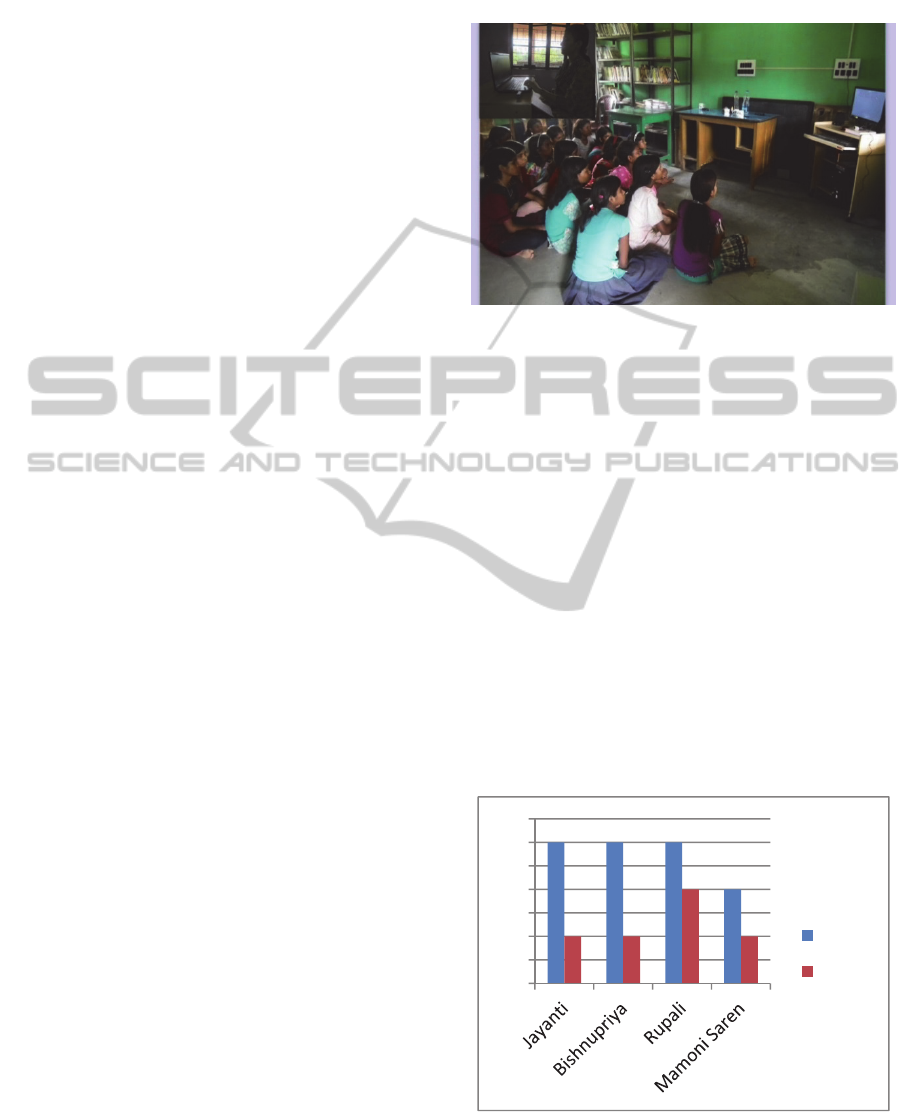

Figure 1: Children Being Taught Remotely (Inset: The

Remote Instructor).

3.1 Methodology

The research is Quasi-experimental in nature and has

undertaken before after studies to evaluate the

impact of the intervention. The before study

entailed the students being ranked on the basis of

their performance in class (more specifically on the

basis of school examination results). The ASER

survey questionnaire for wellbeing assessment and

educational assessment of English has been used.

Next, the students have been ranked on the basis of

their performance after the intervention in English

through ICT. The impact analysis comprises of

assessments and interactive observation with the

students.

3.2 Evaluation

Figure 2: Relative performance of four students of Class-V

based on Results of school exam. and evaluation done

after ICT intervention

0

0,5

1

1,5

2

2,5

3

3,5

ICT

Result

AStudyonthePermeationandScopeofICTInterventionattheIndianRuralPrimarySchoolLevel

367

It can be seen that those who had been near the

bottom of the class benefit the most from this

intervention (fig.2). A majority of the others perform

at the same level as their class performance. Among

the five students of class V who have a normalized

score of 1 in their school exams, three (i.e. 60%)

achieve a normalized score of 3 in the evaluation

conducted post-ICT intervention. Although the

sample size is small, this is a significant finding.

Fig 3. shows the examination performance of 28

Class-I students in (i) the regular school examination

before remote teaching, and (ii) an examination

taken after a month-long remote teaching

intervention in English (20 hours total). The students

have been indexed on the basis of their rank in the

school exam. The chart shows marked

improvements in student performances. Specially,

the students who received very poor marks in school

examination (student number 24 to 28) have shown

significant improvement in their English language

skills. The classes were conducted using Google

plus and the teaching learning materials were video

based and PowerPoints. The method of teaching was

interactive and it was made sure that the children

interacted with the instructor.

Figure 3: Performance Improvement of Class-I Students

after ICT-enabled Remote English Teaching.

The intervention has generated positive results both

in nature of change in attitude towards technology

and learning outcomes. The children were aged

between 6 to 11 years and it was earlier assumed

that it would be difficult for them to cope with

remote teaching due to their lack of attention span.

However during the intervention it was observed

that the children on the contrary did not lose their

attention. The social difference that if often created

between teacher and student due to several

disparities was not observed in this context, the

children were quite aware of the instructor’s

presence online but they did not have any hesitation

in interaction. There was no fear of punishment

although the instructor observed discipline in the

class, but the children did not shy away from the

instructor. Interactive sessions created a positive

learning environment for them, leading to increased

interest in the topics taught.

It can be deduced that technological aids, along

to low/no teacher absenteeism and low social

difference has lead to creation of a better learning

environment. The teacher student ratio being

comparatively low, and the regular interactions with

the teacher also lead to faster learning of concepts.

Video based teaching created better cognitive

understanding of the topics taught. Children were

able to freely interact amongst themselves, and this

also created a positive interest in the topics taught.

Lastly the expectancy created in the children,

increased interest for both instructor and the children

in the classroom.

To summarize, one can make the following

hypotheses about this intervention and, based on the

data obtained, examine whether the nature of results

for each has been positive or negative:

1. The Children Enjoy the ICT-enabled Classes

More in Comparison with Their Usual Class:

We have received positive response from most

of the students on the basis of the questionnaire

and observations. 70% commented that they

found the pictures/videos shown to be very

engaging and interesting. This is natural, since

an audio-visual presentation is more engaging

for children and keeps children attentive longer

than a routine class.

2. An ICT-based Remote Teaching System

Serves to Bring about Higher Teacher

Acceptability: We have received positive

response from most of the students on the basis

of the questionnaire and observations. 89%

students stated that they found the remote

teacher to be highly acceptable. Further, since

there is no physical threat from a “remote”

teacher, the children feel more relaxed in

presence of the teacher. 81 % students have

stated they were mostly able to understand the

remote teaching. There were no negative

responses. Hence, acceptability is generally

high during remote class.

3. An ICT-based Remote Teaching System

Serves to Bring about an Improved

Performance in Many, in Comparison to

School Performance: Although the data set is

0

20

40

60

80

13579111315171921232527

%ofMarksinEnglish

StudentIndexNumber

schoolexam(English)

examafterremoteteaching

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

368

small, and time of intervention was short to

draw any definitive conclusion about this, fig. 2

and fig.3 nonetheless shows marked

improvements in student performances.

Specially, the students who received very poor

marks in school examination have shown

significant improvement in their English

language skills This could be because the ICT-

aided material that was taught was better

understood and retained by the children.

4. The Children Will Fear or Be Skeptical of

New Technology: We have received negative

response from most of the students on the basis

of the questionnaire and observations. Rather,

the children have shown a reasonably ready

acceptance of it, and 81% interviewed have

stated that they are open to change and would

like to be taught in a different way.

5. The Children Would Offer Some Resistance

in Opening up to Outsiders: We have received

negative response from most of the students on

this. Being a close-knit tribal community at a

remote village, with little interaction with the

outer world, it was assumed that the children

would not be open to the idea of complete

strangers instructing or interacting with them.

However, not only did the children show

incredible openness to the idea, they also

engaged very freely in all interactions and

showed extreme enthusiasm.

4 DISCUSSION

AND CONCLUSION

Teachers are expected to enrich a child’s learning

and schooling experience. But this is often not the

case in rural India. Studies have shown that teachers

frequently beat children, terrorize them, and

humiliate them publicly. Many forms of

discrimination and biases enter the classroom. A

recent survey of rural schools, for example, carried

out in West Bengal found disturbing evidence of

primary school teachers showing much less regard

for the interests of children belonging to Scheduled

Castes. Teachers tended to perceive themselves as

belonging to a different and higher class, often the

result of earning much higher incomes than most

parents. They rebuked children for not coming

properly dressed to school, for being obviously dirty,

for being stupid because they belonged to a certain

community. Children were ridiculed for their eating

habits. In some instances, they were made to sit

separately. (Kumar, Rustagi, 2010)

Better-off sections belonging to higher castes are

able to send their children to the fee-charging private

school, which they can afford, for better quality of

education. The poor belonging to lower castes, not

being able to afford private school, are destined to

send their children to inferior quality government

schools. Studies indicate that first; most of the

children enrolled in private schools are from general

caste group, whereas most of the SC and ST children

attend government schools (Aggarwal 2000; Kumar

et al 2005; Mehta 2005; PROBE 1999).

ICT is a significant step in this direction, which

eliminates barriers of regional and gender-based

discrimination by facilitating a high degree of

permeability of education. Since this was a pilot

study, the scope was limited by several constraints,

but we certainly plan on using more sophisticated

tools of e-learning for future interventions.

With regard to the survey conducted at Ma

Sarada Shishu Tirtha, one probable reason for the

ready acceptability of ICT, and the improvement in

performance, could be that, if the teachers in a face

to face teaching situation are from non-tribal

background, a 'social distance' may be created which

operates as a hindrance in learning. This is however

more applicable with respect to weak students. ICT

teaching being neutral to 'social distance' is more

helpful for disadvantaged groups. It is clear that a

long-term intervention is in order, and could prove

to be immensely beneficial if implemented in a

systematic manner.

While “digital inclusion” programs usually tend

to focus on teaching people the usage of computers

and the internet, the approach presented in this study

takes a different perspective. According to this

approach, the entire process of learning should be

oriented towards developing abilities to connect to

the global knowledge network of the cyber‐world

with a specific social context and purpose in mind.

This makes it possible to improve the

underdeveloped communities by obtaining social

inclusion through digital inclusion, and creating

self‐sustainable forms of social development.

REFERENCES

DG Communications Networks & Technology (2013).

Survey of Schools: ICT in Education-Benchmarking

Access, Use and Attitudes to Technology in Europe’s

schools (A study prepared for the European

Commission)

Dreze, J. (2003). Patterns of Literacy and their Social

AStudyonthePermeationandScopeofICTInterventionattheIndianRuralPrimarySchoolLevel

369

Context, in Das V. et al (ed). The Oxford India

Companion of Sociology and Social Anthropology, 2,

Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

Dreze, Jean and Amartya Sen (2002). India: Development

and Participation, Oxford University Press, New

Delhi.

Garrison, D.R. (2011, 20 May). E-Learning in the 21st

Century: A Framework for Research and Practice.

New York: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-203-83876-9

George, K.K. and Reiji Raman (2002). Developments in

Higher Education in India-A Critique, working paper

No.7, Centre for Socio-economic & Environmental

Studies.

Gnanasambandam, Chandra, Anu Madgavkar, Noshir

Kaka, James Manyika, Michael Chui, Jacques Bughin,

Malcolm Gomes (2012). Online and upcoming: The

Internet’s impact on India, McKinsey.

Garg Manisha, Mandal, Kalyan Shankar, (2013). Mid-Day

Meal for the Poor, Privatised Education for the Non-

Poor, Economic & Political Weekly, Vol XLVIII no

30.

Kumar, Anant, (2008). Education of Tribal Children in

Jharkhand: A Situational Analysis, Jharkhand Journal

of Development and Management Studies, XISS,

Ranchi, Vol. 6, No.4 (XXV).

Haddad, Wadi and Sonia Jurich (2002). ICT for

Education: Potential and Potency, in Technologies for

Education: Potentials, Parameters, and Prospects,

eds. Wadi Haddad and A. Drexler (Washington, D.C.:

Academy for Educational Development), 28-40.

InfoDev Essay II: for PriceWaterHouse Coopers (2010).

ICT in School Education (Primary and Secondary)

Kumar, A. K. Shiva and Preeti Rustagi (2010). Elementary

Education in India: Progress, Setbacks, and

Challenges, Oxfam India working papers series,

OIWPS – III

Rajesh, M (2003). A Study of the problems associated with

ICT adaptability in Developing Countries in the

context of Distance Education, Turkish Online Journal

of Distance Education-TOJDE.

Roy, Niraj Kumar (2012). ICT –Enabled Rural Education

in India, International Journal of Information and

Education Technology, Vol. 2, No. 5.

Sen, Amartya and Jean Dreze (2013). An Uncertain Glory:

India and its Contradictions. Allen Lane.

Sen. Amartya, (2003). Development as Capability

Expansion. In: Fukuda-Parr S, et al Readings in

Human Development. New Delhi and New York:

Oxford University Press; 2003.

Vagh, Shaher Banu (2009). Validating the ASER testing

tools: Comparisons with reading fluency measures and

the Read India measures. Technical Paper, ASER

Centre, New Delhi 110 029, India.

Vora, Nikhil and Shweta Dewan (2009). Indian Education

Sector, IDFC SSKI India Research.

Board of Open Learning School: www.bolsd.in/Computer

Aided Learning under SSA: www.ssa.tn.nic.in/

Docu/CAL%202011-ss.pdf

ICT in schools: http://mhrd.gov.in/ict_school

iPerform: www.iperform.classteacher.com

CSEDU2014-6thInternationalConferenceonComputerSupportedEducation

370